68

Cite as You Write

A citation gives credit when credit is due.

Citing sources is how you let readers know that certain information or ideas came from places other than your own head. It also invites them to explore the original source of information should they wish to.

Think of a citation as a giant thank you to the people who said something before you did, or who helped advance your own thinking.

We might not be scholars who need to format citations according to a specified style. But do I have advice around crediting sources anyway? Of course I do.

Here's how writers and creators like us can cite sources:

- Seek out primary, not secondary, sources. A primary source is the originator of an idea, statement, research, or any other material. A secondary source quotes the original source but is not the originator of it.

Maybe this bullet feels like a big duh. But I'm always surprised by how often assets link to a secondary source (another site or writer who's sharing an article) instead of the original.

Track down the primary source! For two reasons: (1) The credibility you gain is worth the extra click or two, and (2) your information will be more accurate since it will not have been inadvertently misinterpreted.

Let's say you post in infographic on your site, for example. Cite the original source and link to it, even if you first discovered it elsewhere.

If you create that infographic based on someone else's data, say that too.

Or if you interview someone and use what she says either directly or indirectly, attribute the ideas to that person, even if you don't use her exact words.

- Freshness matters. The more recent research is, the more accurate and appealing it is. Recency is less of a factor in the social-behavioral sciences, but it does matter in business.

Try to avoid any business research older than four years, since it's likely to be stale. In some fast-evolving industries—technology or social media, say—avoid anything older than two years.

- Wikipedia is not a credible source—even according to Wikipedia itself!1 But it's great for anecdotal or background information, and it can be a handy place to find links to other sources, including original ones.

- Formal citation does have a place in content creation. If you're creating a heftier content asset—say, a book like this one, an ebook, an annual report, a research paper, or a white paper.

You have loads of citation styles to choose from (including those recommended by the Associated Press Stylebook, the Chicago Manual of Style, and so on).

Which one you use isn't all that important; what matters is that you pick one and use it consistently. A tool like Citation Machine (citationmachine.net) delivers a properly formatted citation after you plug in some basic information about what you're referencing and where you found it.

- Citing sources more casually—for example, in a blog post or article—means you link somewhere to the name of the original source (the publication, website, magazine, and so on). You can do it as an aside. But link to the specific post or asset, not just a site's home page.

As always, make sure you have permission to use any intellectual property you're using. Make sure you have permission to use any intellectual property you're using … now in bold. It's that important.

In slide presentations, cite the author right alongside the content any time you use someone else's ideas, text, or images on your slide. As always, make sure you have permission to use them. A single slide at the end with references doesn't cut it.

I know what you're thinking: Won't that junk up my gorgeously crafted slide?

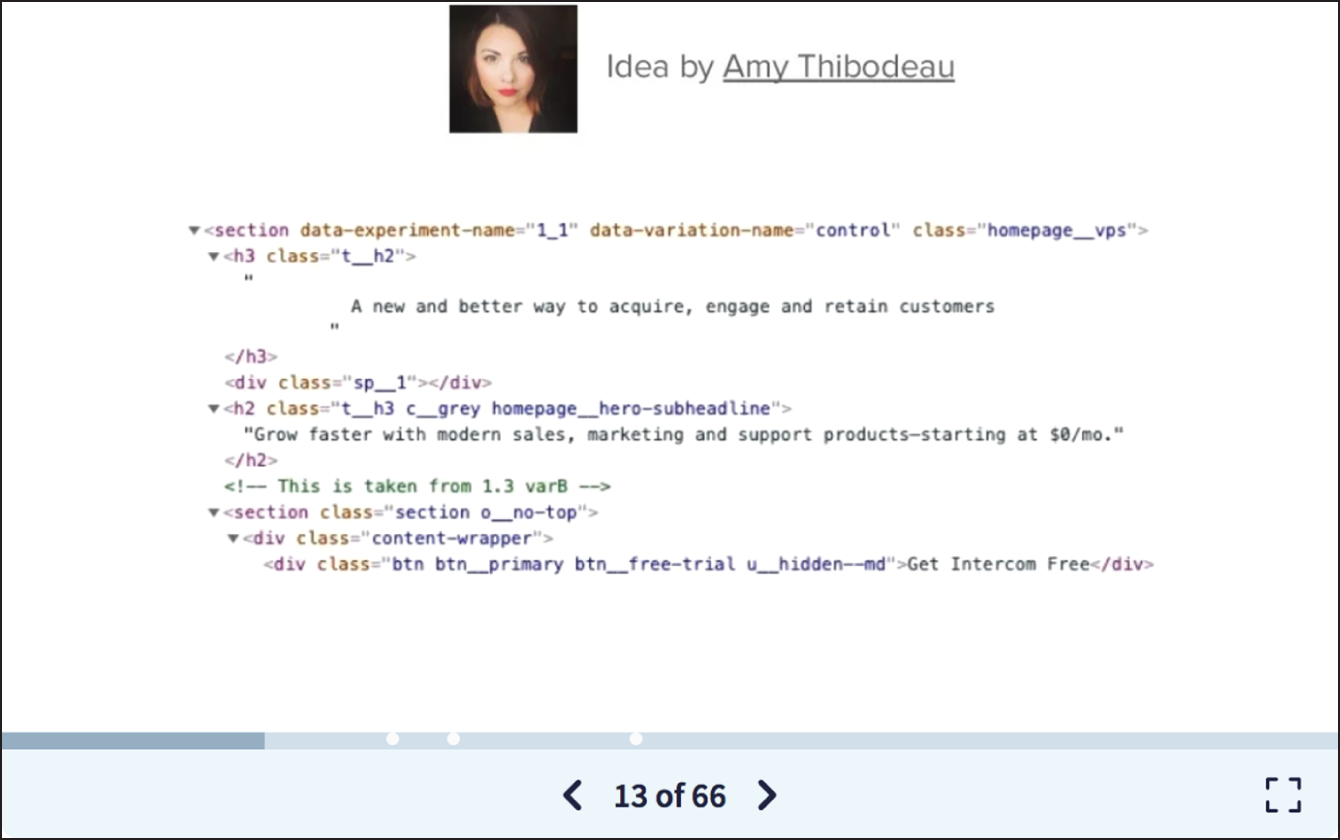

It doesn't have to. See how Jonathon Colman references his colleague Amy Thibodeau as the originator of an idea in his presentation on content design:

Source: Jonathon Colman, Slideshare.net2

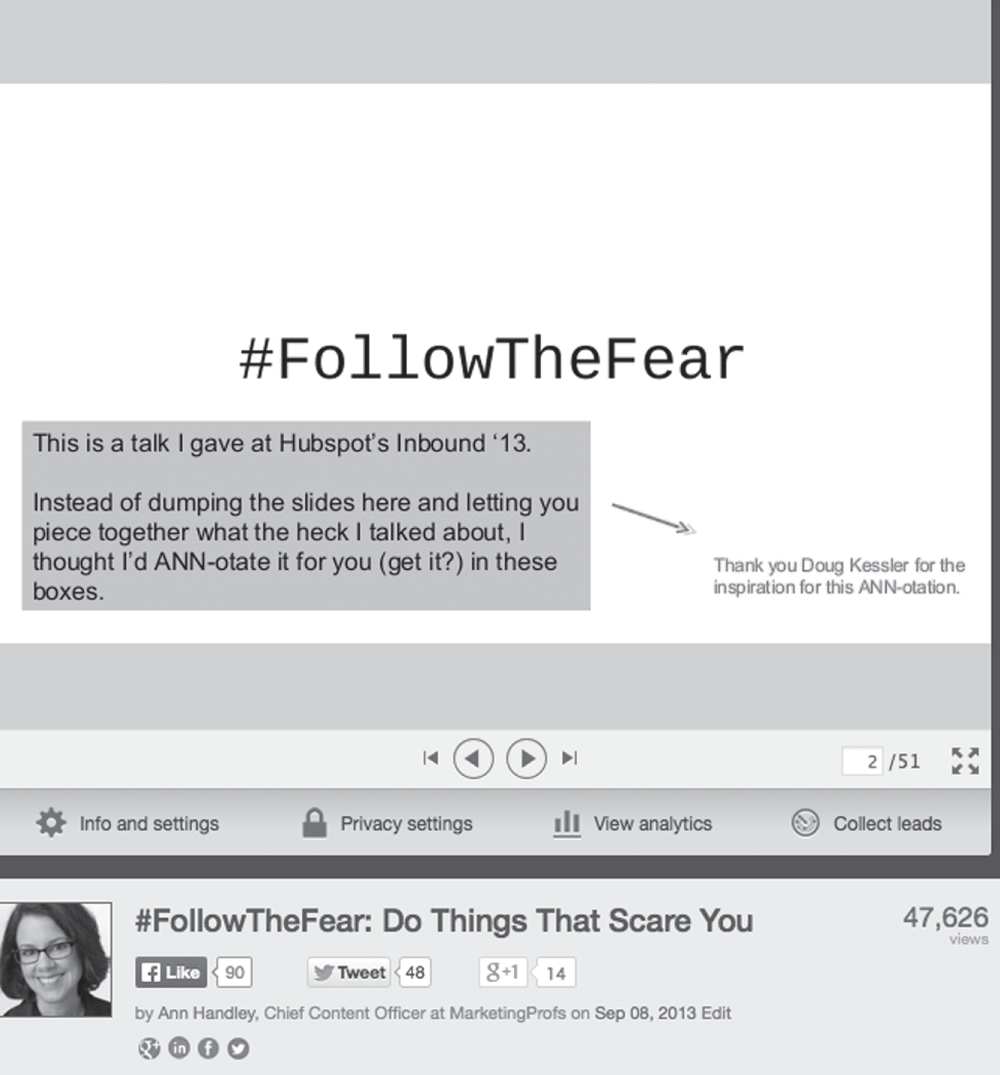

Here's how I gave Doug Kessler at VelocityUK credit for an idea (I also linked to him in the subsequent blog post):

And finally …

- Cite as you write. It's surprisingly easy to forget what idea is your own original work and what you sourced—especially if you let too many hours creep in between the writing and the citing.

This type of memory lapse is actually a thing—psychologist Dan Gilbert calls it kleptomnesia, or an accidental plagiarism or belief that an idea you generate is your own when in fact it was someone else's. (A famous example is George Harrison's 1970 hit “My Sweet Lord,” which a judge later ruled was accidentally similar in both melody and harmony to “He's So Fine” by the Chiffons, a song produced seven years earlier.)

Having access to jillions of sources online is a double-edged sword: It's both liberating and dangerous.

Keep careful notes as you research your work, and mark the origin of excerpts of nonoriginal text in the text itself. Keep in mind that many online tools can instantly crawl through millions of records to see whether your writing is actually yours. (See Part VII.)

One final word on citation: You'll notice that in those two presentation examples I gave, what's cited is actually the source of inspiration for an idea.

Calling out the contributions of others, even if it's merely inspiration, isn't just a good business practice.

It's a good practice, period.

Notes

- 1. “Wikipedia: Wikipedia is not a reliable source,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Wikipedia_is_not_a_reliable_source

- 2. https://www.slideshare.net/jcolman/higher-further-faster-more-from-ux-writing-to-content-design-147390074