Chapter 3

Running Built-In Security Programs

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Making Windows Security work your way

Making Windows Security work your way

![]() Blocking ransomware with controlled folder access

Blocking ransomware with controlled folder access

![]() Coping with SmartScreen

Coping with SmartScreen

![]() Working with UEFI and Secure Boot

Working with UEFI and Secure Boot

![]() Controlling User Account Control

Controlling User Account Control

![]() Understanding Windows Defender Firewall

Understanding Windows Defender Firewall

Windows 11, right out of the box, ships with a myriad of security programs, including a handful that you can control and tweak to offer you the best balance between what you need and how they protect you.

This chapter looks at the things you can do with the programs on offer: Windows Security, Controlled Folder Access for blocking ransomware, SmartScreen for blocking dodgy downloads from the internet, UEFI (don’t judge it by its name alone), User Account Control, and Windows Defender Firewall.

This chapter is a survey of the tip of the iceberg. Even if you don’t change anything, you’ll come away with a better understanding of what’s available and how the pieces fit together. With a little luck, you’ll also have a better idea of what can go wrong, and how you can fix it.

Before we get started, I should warn you that this chapter is more technical than the others, but I make sure to explain all the specialized jargon.

Working with Windows Security

If you’ve ever put up with a bloated and expensive security suite exhorting/extorting you for more money, or you’ve struggled with free antivirus packages that want to install a little toolbar here and a funny monitoring program there — and then ask you for money — you’re in for a refreshing change from an unexpected source.

Windows Security takes over antivirus and antispyware duties and tosses in bot detection, ransomware protection, and antirootkit features for good measure. For years, in independent tests, Microsoft Windows Security has consistently received high detection and removal scores.

This tool has been rebranded many times: from Microsoft Security Essentials to Windows Defender to Windows Defender Antivirus to Windows Defender Security to Microsoft Defender Antivirus, to Windows Security, and from Windows Defender Offline to Microsoft Defender Offline. To make things even more confusing, Microsoft is not consistent about how it names this product in its Windows 11 notifications. Sometimes you see notifications from Windows Security but other times from Microsoft Defender Antivirus. If you search for Windows Defender in Windows 11, you get shortcuts to Windows Defender Firewall, previously known as the Windows Firewall, and not to the antivirus product that you used to know. No matter what Microsoft calls it, Windows Security is just an improved version of the former Windows Defender and now encompasses more security tools in one easy-to-use app.

Windows Security conducts periodic scans and watches out for malware in real time. It vets email attachments, catches downloads, deletes or quarantines at your command, and in general, does everything you’d expect an antivirus, antimalware, and antirootkit product to do.

Is Windows Security the best antivirus package on the market? No. It depends on how you define best, but Microsoft has no intention of coming out on top of the competitive antimalware tests. I think Lowell Heddings said it best, in his “How-To Geek” article (www.howtogeek.com/225385/what’s-the-best-antivirus-for-windows-10-is-windows-defender-good-enough/) in January 2020:

“Other antivirus programs may occasionally do a bit better in monthly tests, but they also come with a lot of bloat, like browser extensions that actually make you less safe, registry cleaners that are terrible and unnecessary, loads of unsafe junkware, and even the ability to track your browsing habits so they can make money. Furthermore, the way they hook themselves into your browser and operating system often causes more problems than it solves. Something that protects you against viruses but opens you up to other vectors of attack is not good security.

Just look at all the extra garbage Avast tries to install alongside its antivirus.

Windows Defender does not do any of these things — it does one thing well, for free, and without getting in your way. Plus, Windows 10 already includes the various other protections introduced in Windows 8, like the SmartScreen filter that should prevent you from downloading and running malware, whatever antivirus you use. Chrome and Firefox, similarly, include Google’s Safe Browsing, which blocks many malware downloads.”

I think Windows 11 All-in-One For Dummies readers tend to be experienced and involved and would agree wholeheartedly.

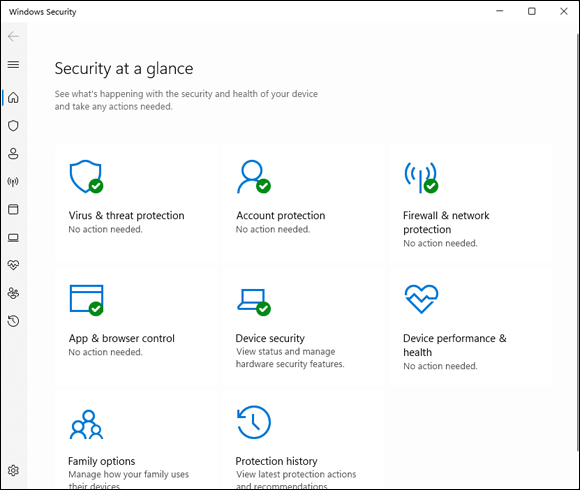

FIGURE 3-1: The Windows Security home page.

When you use Windows Security, you should be aware of these caveats:

It’s never a good idea to run two or more antivirus products simultaneously, and Windows Security is no exception: If you have a second antivirus product running on your machine, Windows Security has been disabled, and you shouldn’t try to bring it back. That’s because each may detect the other as malware, try to access the same system files at the same time, and simply block your computer from functioning.

It’s never a good idea to run two or more antivirus products simultaneously, and Windows Security is no exception: If you have a second antivirus product running on your machine, Windows Security has been disabled, and you shouldn’t try to bring it back. That’s because each may detect the other as malware, try to access the same system files at the same time, and simply block your computer from functioning.- If you don’t like your antivirus product and don’t particularly want to keep paying and paying and paying for it, you should remove it. Open Settings (press Windows+I) and then click or tap Apps. On the right choose Apps & Features. Wait for the list to fill out. Then pick the antivirus program you want to remove and choose Uninstall. Reboot your machine, and Windows Security returns.

- You may see updates listed for Windows Security if you go into Windows Update and look. Just leave them alone. They’ll install all by themselves.

- No matter how you slice it, real-time protection eats into your privacy. How? Say Windows Security (or any other antivirus product) encounters a suspicious-looking file that isn’t on its zap list. In order to get the latest information about that suspicious-looking file, Windows Security has to phone back to Microsoft, drop off pieces of the file, and ask whether there’s anything new. You can opt out of real-time protection, but if you do, you won’t have the latest virus information — and some viruses travel fast.

Adjusting Windows Security

Unlike many other antivirus products, Windows Security has a blissfully small number of things that you can or should tweak. Here’s how to get to the settings:

Click or tap the search icon (magnifying glass) on the taskbar and type sec. At the top, click or tap Windows Security.

The main Windows Security screen appears (refer to Figure 3-1).

Click or tap Virus & Threat Protection and then click or tap the Scan Options link.

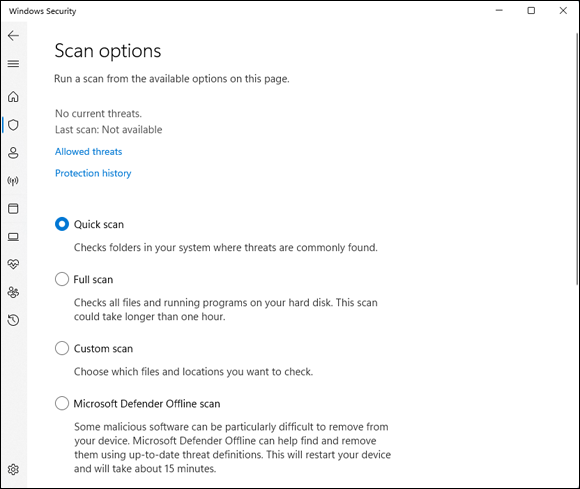

You see the options for manually running a quick scan, full scan, custom scan, or Microsoft Defender Offline scan. (See the “Microsoft Defender Offline” sidebar.) If you go back to Virus & Threat Protection, you can also change Windows Security’s behavior. If you really want to turn off the main antivirus protections, you can do so here.

If you have any reason to fear that your machine’s been taken over by a rootkit, select the Microsoft Defender Offline scan, click or tap Scan Now, and confirm your choice.

You are signed out of Windows 11. Go have a cup of coffee, and by the time you come back, Microsoft Defender Offline will show you a list of any scummy stuff it caught.

Running Windows Security manually

Windows Security works without you doing a thing, but you can tell it to run a scan if something on your computer is giving you the willies. Here’s how:

Click or tap the search icon on the taskbar and type sec. Click or tap Windows Security in the list of search results.

The main Windows Security screen appears (refer to Figure 3-1).

- Click or tap Virus & Threat Protection.

- Under Virus & Threat Protection Updates, click or tap Protection Updates.

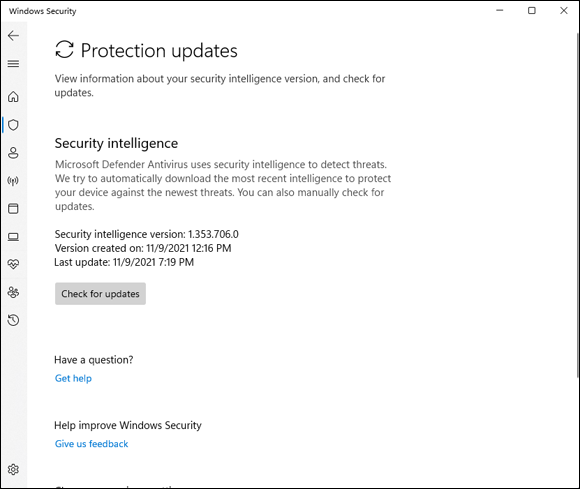

On the resulting Protection Updates pane (see Figure 3-2), click or tap Check for Updates to get the latest antimalware definitions.

When you tap or click Check for Updates, Windows Security retrieves the latest signature files from Microsoft but doesn’t run a scan. If you want to run a scan, you need to go back to the Virus & Threat Protection screen and run it.

FIGURE 3-2: The current status of Windows Security signature file updates.

- Click or tap the back arrow in the top-left corner. Then, to perform a manual scan, click or tap Scan Options. Choose one of the following three options (see Figure 3-3):

- To perform a quick scan, which looks in locations where viruses and other kinds of malware are likely to hide, select the Quick Scan option and then click or tap Scan Now.

- To run a full scan, which runs a bit-by-bit scan of every file and folder on the PC, select the Full Scan option and then click or tap Scan Now.

- To run a custom scan, which is like a full scan, but you get to choose which drives and folders get scanned, select the Custom Scan option, and then click or tap Scan Now and select the folder/partition you want scanned.

FIGURE 3-3: Scan settings for Windows Security.

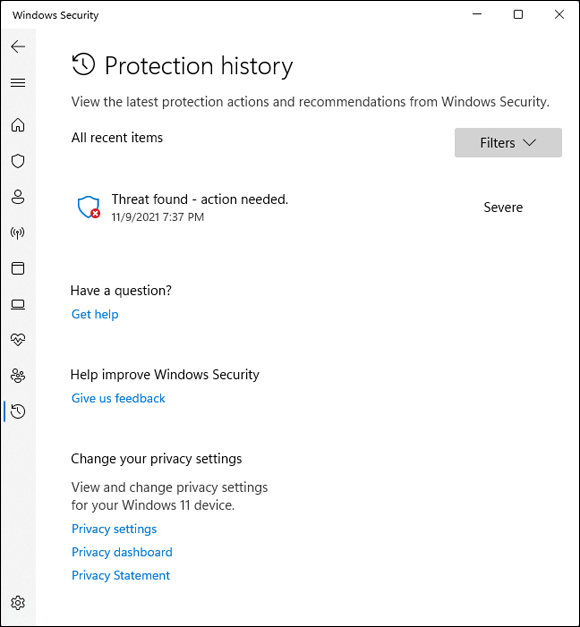

To see what Windows Security has caught and zapped historically, click or tap the Protection History link in the Virus & Threat Protection pane.

The screen shown in Figure 3-4 appears. Once upon a time, Windows Security would flag infected files and offer them up for you to decide what to do with the offensive file. It appears as if that behavior has been scaled back radically. As best I can tell, in almost all circumstances, when Windows Security hits a dicey file, it quarantines the file — sticks it in a place you won’t accidentally find — and just keeps going. You’re rarely notified (although a notification may slide out from the right side of the screen), but the file just disappears from where it should’ve been.

If you just downloaded a file and it disappeared, there’s a good chance that it’s infected and Windows Security has whisked it away to a well-guarded location, and the only way you’ll ever find it is in the Protection History tab of the Windows Security program.

Should you decide to bring the file back, for whatever reason, click or tap the name of the threat, Actions, Allow on Device, and then Yes in the UAC (User Account Control) prompt.

FIGURE 3-4: A full history of the protection actions taken appear here.

Controlling Folder Access

Ransomware — software that scrambles files and demands a payment before unscrambling — has become quite the rage. It’s an easy way for script kiddies to monetize their malware. I talk about ransomware in Book 9, Chapter 1.

Microsoft has come up with a way to preemptively block many kinds of ransomware by simply restricting access to folders that contain files the ransomware may want to zap.

That’s the reason why Microsoft doesn’t turn on Controlled Folder Access (CFA) by default. If you really want CFA, you must dig deep and find it. If you do make the effort, stick CFA on all the right folders and whitelist any program that may need to use files in the controlled folders.

To enable CFA, you need to jump through the following hoops:

- Click or tap the search icon on the taskbar and type sec. Click or tap Windows Security in the list of search results.

Click or tap the Virus & Threat Protection icon, scroll way down, and click or tap Manage Ransomware Protection.

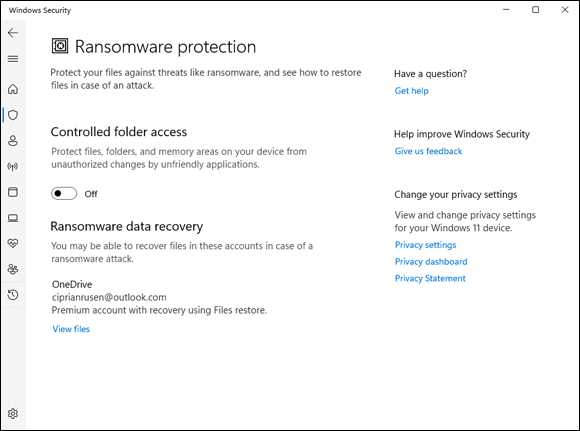

The Controlled Folder Access (CFA) settings screen appears, as shown in Figure 3-5.

FIGURE 3-5: You have to set up Controlled Folder Access manually — and doing so is problematic on many systems.

Set the Controlled Folder Access switch to on and, then click or tap the Protected Folders link. Click or tap Yes when asked to confirm your choice.

You see a list of all folders protected by CFA — Documents, Pictures, Videos, Music, Favorites, and so on. However, ransomware frequently attacks files in other locations too.

If you want to add another folder to the blocked list, click or tap the Add a Protected Folder button and navigate to and select the folder. Repeat as necessary.

Note that Windows has an automatically created (but not disclosed!) set of programs that it deems to be friendly.

- Click or tap the back arrow in the upper-left corner to return to the window shown in Figure 3-5.

- If you have any programs that need access to those folders, and the apps aren’t automatically identified as friendly, click or tap the Allow an App through Controlled Folder Access link, and then click or tap Yes.

Click or tap the Add an Allowed App button, click or tap Browse All Apps, and then navigate to and select the app. Repeat as necessary.

The app is added to the whitelist.

Judging SmartScreen

Have you ever downloaded a program from the internet, clicked to install it — and then, a second later, thought, “Why did I do that?”

Microsoft came up with an interesting technique called SmartScreen that gives you an extra chance to change your mind, if the software you’re trying to install has drawn criticism from other Windows customers. SmartScreen was built into an older version of Internet Explorer, version 7 (it was called Phishing Filter). It’s now part of Windows 11 in Microsoft Edge. Google Chrome and Firefox have similar technologies, but the SmartScreen settings apply only to Internet Explorer (in Windows 10 or older) and in Microsoft Edge.

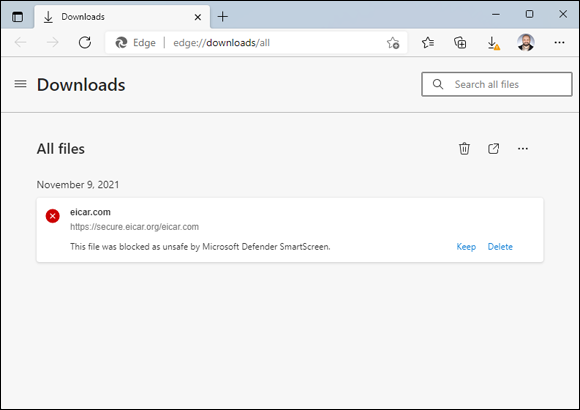

One part of SmartScreen works with Windows Security. In fact, sometimes I’ve seen an infected file trigger a notification from Windows Security, and later had the same infected file prompt the SmartScreen warning shown in Figure 3-6.

FIGURE 3-6: SmartScreen may take the credit for the bust, but Windows Security did the work.

If you don’t run the program, it gets stuffed into the same location that Windows Security puts its quarantined programs — out of the way where you can’t find it, unless you go in through Windows Security’s Protection History tab (refer to Figure 3-4).

There’s a second part of SmartScreen that works differently, something like this:

You download something — anything — from the internet.

Most browsers and many email programs and other online services (including instant messengers) set a property on the downloaded file that indicates where the file came from.

- When you try to launch the file, Windows 11 checks the name of the file and the URL of origin to see whether they’re on a trusted whitelist.

- If the file doesn’t pass muster, you see a notification like the one in Figure 3-6.

The more people who install the program from that site, the more trusted the program becomes.

Again, Microsoft is collecting information about your system — in this case, about your downloads — but it’s for a worthy cause.

Microsoft has an excellent, official description of the precise way the tracking mechanism works at https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-edge/what-is-smartscreen-and-how-can-it-help-protect-me-1c9a874a-6826-be5e-45b1-67fa445a74c8.

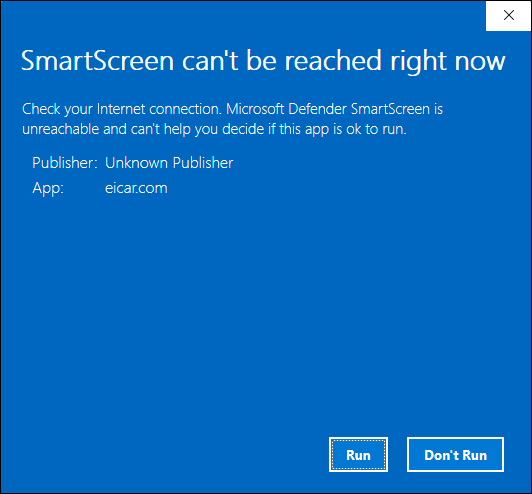

So what can go wrong? Not much. If SmartScreen can’t make a connection to its main database when it hits something fishy, you see a blue screen like the one in Figure 3-7 telling you that SmartScreen can’t be reached right now. The connection can be broken for many reasons, such as the Microsoft servers go down or maybe you downloaded a program and decided to run it later. When that happens, if you can’t get your machine connected, you’re on your own.

FIGURE 3-7: If SmartScreen can’t phone home, it leaves you on your own.

Normally, overriding a SmartScreen warning requires the okay of someone with an administrator account. You can change that, too. Here’s how:

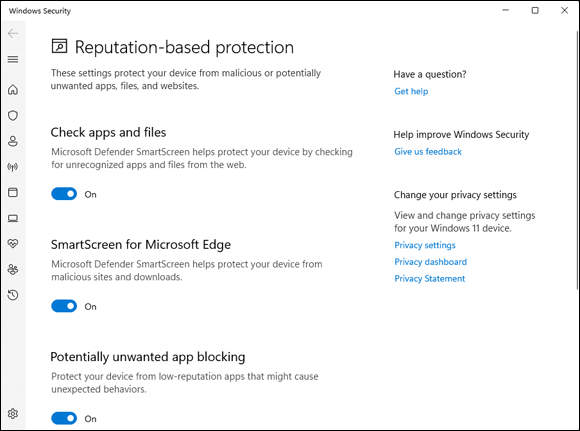

Click or tap the search icon and type smartscreen. Click or tap the Reputation-Based Protection search result.

The Windows Security Reputation-Based Protection pane appears (see Figure 3-8).

FIGURE 3-8: Think twice before turning off SmartScreen.

(Optional) To change the default warning behavior for SmartScreen when you run it on downloaded files, click or tap the switch for Check Apps and Files. Click or tap Yes when asked to confirm your choice.

You won't receive a warning when something bad is downloaded by Google Chrome, Firefox, or any non-Microsoft browser, but you will be warned if you try to open or run the file.

- (Optional) To change the default warning behavior for Edge, adjust the SmartScreen For Microsoft Edge switch.

(Optional) Turn off SmartScreen for potentially unwanted Apps as well as for Microsoft Store apps by setting the last two switches to off. Click or tap Yes when asked to confirm your choice.

Don’t forget to close Windows Security when done. Also, its icon in the notification area will be busy with warning messages.

Booting Securely with UEFI

If you’ve ever struggled with your PC’s BIOS — or been kneecapped by a capable rootkit — you know that BIOS should’ve been retired more than a decade ago.

Windows 11 pulled the industry kicking and screaming out of the BIOS generation and into a far more capable Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI). Although UEFI machines in the time of Windows 7 were unusual, starting with Windows 8, every new machine with a Runs Windows sticker is required to have UEFI; it’s part of the licensing requirement. Windows 11 enforces this requirement by refusing to install on non-UEFI systems.

A brief history of BIOS

To understand where Windows is headed, it’s best to look at where it’s been. And where it’s been with BIOS inside PCs spans the entire history of the personal computer. That makes PC-resident BIOS more than 40 years old. The first IBM PC had a BIOS, and it didn’t look all that different from the inscrutable one you swear at now.

The Basic Input/Output System, or BIOS, is a program responsible for getting all your PC’s hardware in order and then firing up the operating system (OS) — in this case, Windows — and finally handing control of the computer over to the OS. BIOS runs automatically when the PC is turned on.

Older operating systems, such as DOS, relied on the BIOS to perform input and output functions. More modern operating systems, including Windows, have their own device drivers that make BIOS control obsolete, after the OS is running.

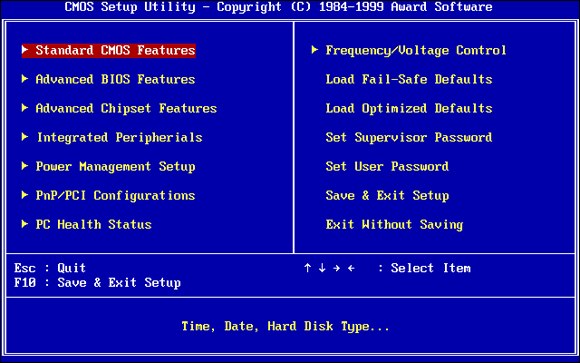

Every BIOS has a user interface, which looks much like the one in Figure 3-9. You press a key while the BIOS is starting and, using different keyboard incantations, take some control over your PC’s hardware, select boot devices (in other words, tell BIOS where the operating system is located), overclock the processor, disable or rearrange hard drives, and the like.

FIGURE 3-9: The AwardBIOS Setup Utility.

How UEFI is different from and better than BIOS

BIOS has all sorts of problems, not the least of which is its susceptibility to malware. Rootkits like to hook themselves into the earliest part of the booting process — permitting them to run underneath Windows — and BIOS has a big Kick Me sign on its tail.

Unlike BIOS, which sits inside a chip on your PC’s motherboard, UEFI can exist on a disk, just like any other program, or in non-volatile memory on the motherboard or even on a network share.

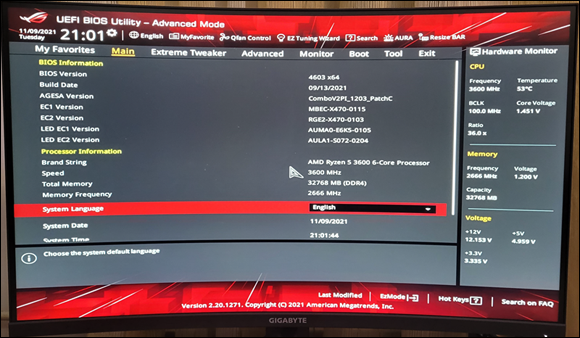

UEFI is very much like an operating system that runs before your final operating system kicks in. UEFI has access to all the PC’s hardware, including the mouse and network connections. It can take advantage of your fancy video card and monitor, as shown in Figure 3-10. It can even access the internet. If you’ve ever played with BIOS, you know that this is in a whole new dimension.

FIGURE 3-10: The UEFI interface on an ASUS PC.

Compare Figure 3-9 with Figure 3-10, and you’ll have some idea where technology’s been and where it’s heading.

BIOS — the entire process surrounding BIOS, including POST — takes a long, long time. UEFI, by contrast, can go by quite quickly. The BIOS program itself is easy to reverse-engineer and has no internal security protection. In the malware maelstrom, it’s a sitting duck. UEFI can run in any malware-dodging way its inventors contrive.

Dual boot in the old world involves a handoff to a clunky text program; in the new world, it can be much simpler, more visual, and controlled by mouse or touch.

More to the point, UEFI can police operating systems before loading them. That could make rootkit writers’ lives considerably more difficult by, for example, refusing to run an OS unless it has a proper digital security signature. Windows Security can work with UEFI to validate OSs before they’re loaded. And that’s where the controversy begins.

How Windows 11 uses UEFI

A UEFI Secure Boot option validates programs before allowing them to run. If Secure Boot is turned on, operating system loaders have to be signed using a digital certificate. If you want to dual boot between Windows 11 and Linux, the Linux program must have a digital certificate — something Linux programs have never required before.

After UEFI validates the digital key, UEFI calls on Windows Security to verify the certificate for the operating system loader. Windows Security (or another security program) can go out to the internet and check to see whether UEFI is about to run an OS that has had its certificate yanked.

In essence, in a dual-boot system, Windows Security decides whether an operating system gets loaded on your Secure Boot-enabled machine.

That curls the toes of many Linux fans. Why should their operating systems be subject to Microsoft’s rules, if you want to dual boot between Windows 11 and Linux?

If you have a PC with UEFI and Secure Boot and you want to boot an operating system that doesn’t have a Microsoft-approved digital signature, you have two options:

- You can turn off Secure Boot.

- You can manually add a key to the UEFI validation routine, specifically allowing that unsigned operating system to load.

Controlling User Account Control

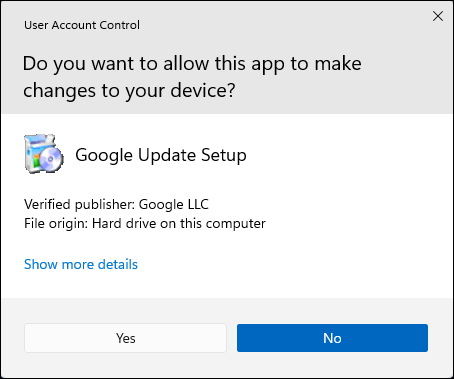

User Account Control (UAC) is a pain in the neck, but then again, it’s supposed to be that. If you try to install a program that’s going to make system-level changes, you may see the obnoxious prompt in Figure 3-11.

FIGURE 3-11: User Account Control tries to keep you from clobbering your system.

UAC’s a drama queen, too. The approval dialog box in Figure 3-11 appears front and center, but at the same time, your entire desktop dims, and you’re forced to deal with the UAC prompt.

If you go into your system folders manually or if you fire up the Editor and start making loose and fancy with registry keys, UAC figures you know what you’re doing and leaves you alone. But the minute a program tries to do those kinds of things, Windows warns you that a potentially dangerous program is on the prowl and gives you a chance to kill the program in its tracks.

Windows lets you adjust User Account Control so it isn’t quite as dramatic — or you can get rid of it entirely.

To adjust your computer’s UAC level, follow these steps:

Click or tap the search icon and type uac. At the top of the ensuing list, choose Change User Account Control Settings.

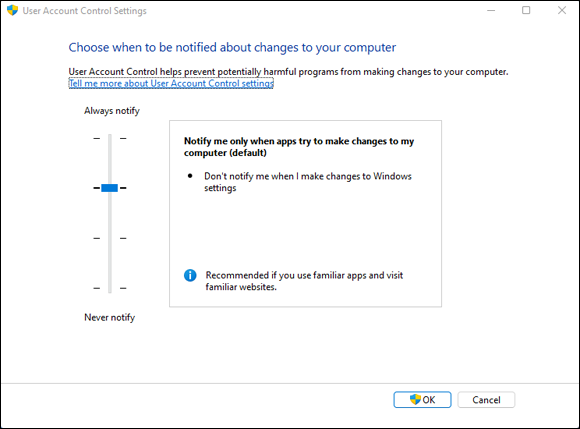

The slider shown in Figure 3-12 appears.

FIGURE 3-12: Windows 11 allows you to change the level of UAC intrusiveness.

Adjust the slider according to Table 3-1, and then click or tap OK.

Perhaps surprisingly, as soon as you try to change your UAC level, Windows 11 hits you with a User Account Control prompt. If you’re using a standard account, you have to provide an administrator username and password (or PIN) to make the change. If you’re using an administrator account, you must confirm the change.

Click or tap Yes.

Your changes take effect immediately.

TABLE 3-1 User Account Control Levels

Slider | What It Means | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

Level 1 (top) | Always brings up the full UAC notification whenever a program tries to install software or make changes to the computer that require an administrator account, or when you try to make changes to Windows settings that require an administrator account. You see these notifications even if you're using an administrator account. The screen blacks out, and you can’t do anything until the UAC screen is answered. | This level offers the highest security but also the highest hassle factor. |

Level 2 | Brings up the UAC notification whenever a program tries to make changes to your computer, but generally doesn’t bring up a UAC notification when you make changes directly. | The default — and probably the best choice. |

Level 3 | This level is the same as Level 2 except that the UAC notification doesn't lock and dim your desktop. | Potentially problematic. Dimming and locking the screen present a high hurdle for malware. |

Level 4 (bottom) | UAC is disabled — programs can install other programs or make changes to Windows settings, and you can change anything you like, without triggering any UAC prompts. Note that this doesn't override other security settings. For example, if you're using a standard account, you still need to provide an administrator's ID and password before you can install a program that runs for all users. | Automatically turns off all UAC warnings — NOT recommended. |

UAC-level rules are interpreted according to a special Windows security certificate. Programs signed with that certificate are deemed to be part of Windows. Programs that aren’t signed with that specific certificate are outside Windows and thus trigger UAC prompts if your computer is at Level 1, 2, or 3.

Poking at Windows Defender Firewall

A firewall is a program that sits between your computer and the internet, protecting you from the big, mean, nasty gorillas riding around on the information superhighway. An inbound firewall acts like a traffic cop that allows only good stuff into your computer and keeps all the bad stuff out on the internet, where it belongs. An outbound firewall prevents your computer from sending bad stuff to the internet, such as when your computer becomes infected with a virus or has another security problem.

Windows includes a decent inbound firewall. It also includes a snarly, hard-to-configure, rudimentary outbound firewall, which has all the social graces of a junkyard dog. Unless you know the magic incantations, you never even see the outbound firewall — it’s completely muzzled unless you dig into the Windows doghouse and teach it some tricks.

Outbound firewalls tend to bother you mercilessly with inscrutable warnings saying that obscure processes are trying to send data. If you simply click through and let the program phone home, you’re defeating the purpose of the outbound firewall. On the other hand, if you take the time to track down every single outbound event warning, you may spend half your life dealing with prompts from your firewall.

I think outbound firewalls are mostly a waste of time. Although I’m sure some people have been alerted to Windows infections when their outbound firewall goes bananas, most of the time, the outbound warnings are just noise. Outbound firewalls don’t catch the cleverest malware, anyway. However, I have a few friends who insist on running an outbound firewall. If you want one too, I recommend GlassWire, which is available in a free-for-personal-use version at www.glasswire.com

Understanding Defender Firewall basic features

All versions of Windows 11 ship with a decent and capable, but not foolproof, stateful firewall named Windows Defender Firewall (WDF). (See the nearby sidebar, “What’s a stateful firewall?”)

Windows Defender Firewall inbound protection is on by default. Unless you change something, Windows Defender Firewall is turned on for all connections on your PC. For example, if you have a LAN cable, a wireless networking card, and a 4G USB card on a specific PC, WDF is turned on for them all. The only way Windows Defender Firewall gets turned off is if you deliberately turn it off or if the network administrator on your big corporate network decides to disable it by remote control or install Windows with Windows Defender Firewall turned off.

You can change WDF settings for inbound protection relatively easily. When you make changes, they apply to all connections on your PC. On the other hand, WDF settings for outbound protection make the rules of cricket look like child’s play.

WDF kicks in before the computer is connected to the network. Back in the not-so-good old days, many PCs got infected between the time they were connected and when the firewall came up.

Speaking your firewall’s lingo

At this point, I must go through a bunch of jargon so that you can take control of Windows Defender Firewall. Hold your nose and dive in. The concepts aren’t that difficult, although the terminology sounds like a first-year advertising student invented it. Refer to this section if you become bewildered when wading through the WDF dialog boxes.

As you no doubt realize, the amount of data that can be sent from one computer to another over a network can be tiny or huge. Computers talk with each other by breaking the data into packets (or small chunks of data with a wrapper that identifies where the data came from and where it’s going).

On the internet, packets can be sent in two ways:

- User Datagram Protocol (UDP): UDP is fast and sloppy. The computer sending the packets doesn’t keep track of which packets were sent, and the computer receiving the packets doesn’t make any attempt to get the sender to resend packets that vanish mysteriously into the bowels of the internet. UDP is the kind of protocol (transmission method) that can work with live broadcasts, where short gaps wouldn’t be nearly as disruptive as long pauses, while the computers wait to resend a dropped packet.

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP): TCP is methodical and complete. The sending computer keeps track of which packets it has sent. If the receiving computer doesn’t get a packet, it notifies the sending computer, which resends the packet. These days, almost all communication over the internet goes by way of TCP.

Peeking into your firewall

When you use a firewall — and you should — you change the way your computer communicates with other computers on the internet. This section explains what Windows Defender Firewall does behind the scenes so that when it gets in the way, you understand how to tweak it. (You find the ins and outs of working around the firewall in the “Making inbound exceptions” section, later in this chapter.)

Windows Defender Firewall works by handling all these duties simultaneously:

- It keeps track of outgoing packets and allows incoming packets to go through the firewall if they can be matched with an outgoing packet. In other words, WDF works as a stateful inbound firewall.

- If your computer is attached to a private network, Windows Defender Firewall allows packets to come and go on ports 139 and 445, but only if they came from another computer on your local network and only if they’re using TCP. Windows Defender Firewall needs to open those ports for file and printer sharing. It also opens several ports for Windows Media Player if you’ve chosen to share your media files, for example.

- Similarly, if your computer is attached to a private network, Windows Defender Firewall automatically opens ports 137, 138, and 5355 for UDP, but only for packets that originate on your local network.

- If you specifically told Windows Defender Firewall that you want it to allow packets to come in on a specific port and the Block All Incoming Connections check box isn’t selected, WDF follows your orders. You may need to open a port in this way for online gaming, for example.

- Windows Defender Firewall allows packets to come into your computer if they’re sent to the Remote Assistance program, as long as you created a Remote Assistance request on this PC and told Windows to open your firewall (see Book 7, Chapter 3). Remote Assistance allows other users to take control of your PC, but it has its own security settings and strong password protection. Still, it’s a known security hole that’s enabled when you create a request.

- You can tell Windows Defender Firewall to accept packets directed at specific programs. Usually, any company that makes a program designed to listen for incoming internet traffic (Skype is a prime example, as are any instant-messaging apps) adds its program to the list of designated exceptions when the program is installed.

- Unless an inbound packet meets one of the preceding criteria, it’s simply ignored. Windows Defender Firewall swallows it without a peep. Conversely, unless you’ve changed something, any and all outbound traffic goes through unobstructed.

Making inbound exceptions

Firewalls can be infuriating. You may have a program that has worked for a hundred years on all sorts of computers, but the minute you install it on a Windows 11 machine with Windows Defender Firewall in action, it just stops working, for absolutely no apparent reason.

You can get mad at Microsoft and scream at Windows Defender Firewall, but when you do, realize that at least part of the problem lies in the way the firewall has to work. (See the “Peeking into your firewall” section, earlier in this chapter, for an explanation of what your firewall does behind the scenes.) It has to block packets that are trying to get in, unless you explicitly tell the firewall to allow them to get in.

Perhaps most infuriatingly, WDF blocks those packets by simply swallowing them, not by notifying the computer that sent the packet. Windows Defender Firewall has to remain stealthy because if it sends back a packet that says, “Hey, I got your packet, but I can’t let it through,” the bad guys get an acknowledgment that your computer exists, they can probably figure out which firewall you’re using, and they may be able to combine those two pieces of information to give you a headache. It’s far better for Windows Defender Firewall to act like a black hole.

Some programs need to listen to incoming traffic from the internet; they wait until they’re contacted and then respond. Usually, you know whether you have this type of program because the installer tells you that you need to tell your firewall to back off.

To poke a hole in the inbound Windows Defender Firewall for a specific program:

- Make sure that the program you want to allow through Windows Defender Firewall is installed.

Click or tap the search icon and type firewall. Choose Allow an App through Windows Firewall.

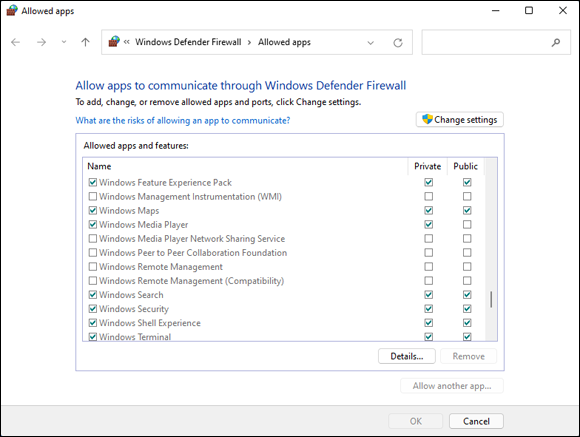

Windows Defender Firewall presents you with a lengthy list of apps that you may want to allow (see Figure 3-13). If a box is selected, Windows Defender Firewall allows unsolicited incoming packets of data directed to that program and that program alone, and the column tells you whether the connection is allowed for private or public connections.

These settings don’t apply to incoming packets of data that are received in response to a request from your computer; they apply only when a packet of data appears on your firewall’s doorstep without an invitation.

These settings don’t apply to incoming packets of data that are received in response to a request from your computer; they apply only when a packet of data appears on your firewall’s doorstep without an invitation.

FIGURE 3-13: Allow installed programs to poke through the firewall.

In Figure 3-13, the Windows Maps app is allowed to receive inbound packets whether you’re connected to a private or public network. Windows Media Player, on the other hand, may accept unsolicited inbound data from other computers only if you’re connected to a private network: If you’re attached to a public network, inbound packets headed for Windows Media Player are swallowed by the Windows Defender Firewall Black Hole (patent pending).

Click or tap Change Settings, and do one of the following:

- If you can find the program that you want to poke through the firewall listed in the Allow Programs list, select the check boxes that correspond to whether you want to allow the unsolicited incoming data when connected to a home or work network and whether you want to allow the incoming packets when connected to a public network. It’s rare indeed that you’d allow access when connected to a public network but not to a home or work network.

- If you can’t find the program that you want to poke through the firewall, you need to go out and look for it. Click or tap the Allow Another App button at the bottom and then click or tap Browse.

Windows Defender Firewall goes out to all common program locations and finally presents you with the Whack a Mol … er, Add an App list like the one shown in Figure 3-14. It can take a while.

FIGURE 3-14: Allow a program (that you’ve thoroughly vetted!) to break through the firewall.

Browse to the program’s location and select it. Then click or tap Open, and then Add.

You return to the Windows Defender Firewall Allowed Apps list (refer to Figure 3-13), and your newly selected program is now available.

Select the check boxes to allow your poked-through program to accept incoming data while you’re connected to a private or a public network. Then click or tap OK.

Your poked-through program can immediately start handling inbound data.

Microsoft maintains an active online support forum for Windows Security at Microsoft Answers,

Microsoft maintains an active online support forum for Windows Security at Microsoft Answers,  There’s just one problem. Restricting, or controlling, folder access is a pain in the neck — it blocks every program unless you specifically give a specific program access. So, for example, you can turn off access to your Documents folder but allow access to Word and Excel. That may work well until you want to run Notepad on a file in the Documents folder.

There’s just one problem. Restricting, or controlling, folder access is a pain in the neck — it blocks every program unless you specifically give a specific program access. So, for example, you can turn off access to your Documents folder but allow access to Word and Excel. That may work well until you want to run Notepad on a file in the Documents folder. UEFI and BIOS can coexist: UEFI can run on top of BIOS, hooking itself into the program locations where the operating system may call BIOS, basically usurping all the BIOS functions after UEFI gets going. UEFI can also run without BIOS, taking care of all the runtime functions. The only thing UEFI can’t do is perform the power-on self-test (POST) or run the initial setup. PCs that have UEFI without BIOS need separate programs for POST and setup that run automatically when the PC is started.

UEFI and BIOS can coexist: UEFI can run on top of BIOS, hooking itself into the program locations where the operating system may call BIOS, basically usurping all the BIOS functions after UEFI gets going. UEFI can also run without BIOS, taking care of all the runtime functions. The only thing UEFI can’t do is perform the power-on self-test (POST) or run the initial setup. PCs that have UEFI without BIOS need separate programs for POST and setup that run automatically when the PC is started.