CHAPTER 1

Understanding Organizations: Social Systems, Not Machines

A company is a multidimensional system capable of growth, expansion, and self-regulation. It is, therefore, not a thing but a set of interacting forces. Any theory of organization must be capable of reflecting a company's many facets, its dynamism, and its basic orderliness. When company organization is reviewed, or when reorganizing a company, it must be looked upon as a whole, as a total system.

—Albert Low Zen and Creative Management

“If you to want truly to understand something, try to change it,” the psychologist and organizational development pioneer Kurt Lewin is said to have declared. Over the course of the past few decades, my colleagues and I have tried to change numerous organizations—from small startups to well-established mid-sized businesses to massive multinational enterprises.

In the process, I have indeed come to understand a thing or two about these strange beasts. It's not the most elegant way to learn, especially when starting out, since the true nature of an entity is often revealed as it resists efforts at transformation. It's only when you start trying to move the pieces that you see how they're all connected, what keeps them in place, and what animates them. And more often than not, what you discover forces you to rethink your approach. I'm still learning, to this day, but what I can say with confidence is that the more I've learned about what an organization is, the more effective I've become as an agent of change. It is my hope that this learned knowledge may enable me to reverse that quotation for my readers and help you to avoid at least some of the trial and error. If you want to truly change something, try to understand it first. Otherwise, you won't get very far. At this point in this book, I invite you to pause and consider the question, What is an organization?

Many leaders think an organization is just a business, and their job is simply to run it. If only it were so simple. In fact, the strictly “business” part of an enterprise—the shared work we do to develop, sell, and deliver a product or service to customers—is only part of the endeavor. (That doesn't mean it's not critical—we'll come back to this definition of a business and how to optimize it in Chapter 2, when we introduce the Business Triangle®.) If you're a one-person company doing everything yourself, the business may be all you need to focus on. But the minute you want to grow or scale your company, you have to do something else. You have to deal with people. You must persuade people to join you and motivate them to come along on the journey with you. You must figure out how to inspire people to cooperate, to collaborate, and to become leaders in their own right. And, newsflash: people can be messy, complicated, and difficult—especially when you're dealing with groups of them. There is no getting around this truth.

But along with all of that messiness comes incredible potential. That's why, when we want to achieve things that matter, we form organizations: because we know that we can do so much more together than we could ever do alone. And not just by bending others to our will, but by working to unleash their creativity and intelligence. People can be difficult but they can also be original, innovative, caring, and independent. They can be complicated, but they can surprise you with their commitment and capabilities. Which brings us to the question that has spawned a thousand books about leadership: How do we get from messy, complicated, and dispersed to capable, creative, and aligned? If an organization is much more than a business, what's the best approach to managing it, leading it, and growing it? The answer starts with how we see it.

Metaphors matter. As storytelling creatures, when confronted with a complicated, multidimensional, somewhat abstract entity like an organization, we tend to look for images that help us to describe it and make sense of it. We need something we can visualize. And these metaphors we choose will inevitably shape not just the way we talk about our organizations, but how we respond to them and how we lead them.

For example, it's common for leaders and change-management experts today to talk about organizations as if they were machines or computers. Machines have parts, which either work or break down, in which case they need to be repaired or replaced. They have inputs and outputs. Sometimes, they need tune-ups, new engines, or software updates. It's a convenient metaphor, pleasingly concrete. There's just one problem: actual organizations don't work like machines. Businesses are not body shops. And people don't respond well to being treated like parts that either function well or are deficient. If you think simply replacing all your dysfunctional parts or installing the latest trendy management theory like a software update is the answer to building a high-performing organization, you will be in for a long, difficult journey.

One of the central shortcomings of the mechanistic approach is that it sees the whole as being simply the sum of the parts, and the parts as being essentially predictable and self-contained. As anyone who's tried to lead a team of people knows, this could not be farther from the truth. An organization is much more than the sum of the people involved—that's what makes it powerful, but also challenging to manage. And those people are anything but predictable, while being profoundly interconnected. In this sense, as in many others, the machine metaphor is a poor fit and gives rise to leadership approaches that are limited at best. And yet this metaphor—and the perspective and management methods it spawns—is surprisingly persistent in the business community today.

Metaphors matter. How we frame problems and opportunities in our organizations creates the expectations, solution-sets, and “possibility space” in which we operate. A limited metaphor tends to limit our thinking. So, if organizations are not machines, how might we understand them better? What metaphors or images might we adopt to help us describe and guide them? I've come to the conclusion that that best way to see—and lead—an organization is as a system. More specifically, as a complex, adaptive social system.

That may not be as conveniently concrete as a machine or a computer, but it's a more accurate and therefore more powerful way to understand the human dynamics involved. Organizations are not machines subject to immutable laws of physics, they are human systems subject to the more complex social dynamics of relationships. I've found that this shift of metaphor works with leaders and teams to release and make visible their mental frameworks and consequently opens the door for them to envision and lead transformations that otherwise might have seemed impossible. Leaders and team members must become systems thinkers—able to visualize and model the ways in which the elements of the system interact and transform. The Growth River approach to creating high-performing teams and companies is based on this fundamental premise: teams and organizations are complex, adaptive, social systems.

“Complex adaptive system” is a term that comes out of the science of complexity theory. It refers to any system—whether in the natural world, in technology, or in human culture—in which the behavior of the system as a whole cannot be explained simply by looking at the individual parts. It is a system that has something called swarm intelligence—a population of decentralized agents that interact with each other to self-organize around shared purpose and aligned behaviors. For example, think about an ecosystem, an ant colony, the flow of urban traffic, an economy, a language, the human immune system, the Internet, a cell, a nation. In each of these diverse examples, the system has its own properties that cannot always be predicted by understanding the parts. It exhibits self-organizing, or emergent, behavior. You could study an individual bee for years and never fully understand the behavior of a hive. You could analyze a single blood cell from every conceivable angle and not come close to grasping the functioning of the circulatory system. You could memorize every word of an unfamiliar language yet have no ability to use it to communicate.

Complex adaptive systems occur in the natural world and in the human world, but when it comes to human systems, we add the term social. In such systems, the complexity is increased by the fact that the system is made up of individual people, each possessing a degree of agency—the ability to choose, adapt, surprise, change direction, as well as create and collaborate in new and interesting ways. Each agent in this system has a unique mental and emotional universe, an interior, subjective world that influences their choices in ways that are hard, if not impossible, to predict or control. At times, that can make everything immensely more difficult and confusing, and yet, the good news is that it makes so much more possible.

One of the most remarkable things about human beings is our ability to intentionally organize around a shared goal or purpose and in so doing, to achieve things we could never do alone. You might be a brilliant medical scientist who invents a powerful new drug to cure cancer, but if it's just you in your lab, you won't save many lives. You need others to help you manufacture the drug, test it and ensure it's safe, sell it, distribute it, and so on. Or perhaps you're passionate about combating climate change and you come up with a way to generate more efficient energy from solar panels. If you only install it on your own roof, you aren't going to make much of a difference to net carbon emissions. But if you can create an organization to manufacture, sell, and promote your product to tens of thousands of households, you could have a significant impact.

Complex adaptive social systems include all manner of human groupings, from tribes, political parties, sports teams, and religious communities to terrorist groups, gangs, and cults. The term is fittingly applied to business organizations as well. A human organization does not behave like a collection of molecules interacting to create a cell. It doesn't pattern itself like a colony of bacteria, or even the complex interactions of plants, animals, insects, and climate that make up an ecosystem. Although it may have a lot in common with all these systems, the human element adds another dimension to the mix.

When people talk about complex adaptive social systems in complexity theory, they often refer to ants. Ants are a favorite of scientists, in part because of their unique organizing capabilities. They get so much done! They constantly toil, build, and expand their colonies. They exhibit self-organization, division of labor, and can adapt to changing circumstances. And they do it all with only a few types of ants fulfilling a few roles and with brains the size of a microliter (albeit quite large relative to their size). Like ants, humans have the ability to organize, solve problems as a group, and exhibit remarkable feats of collective intelligence. But we do it on a completely different scale of complexity. But it's not only the brain size that makes a difference; it's the balance between our individual agency and our social natures. Humans can collectively organize in large groups, while retaining a high degree of individual capacity for creativity and agency. Indeed, with all due respect to the remarkable feats of our insect friends, human potential for dynamic, creative, collective intelligence is off the charts.

You might think that's obvious, but there are many organizational approaches that assume people are not that different to ants—that we are merely Pavlovian creatures of instinct and incentive. Of course, humans certainly do respond to incentives, and are partially driven by instinct, but that is not all that is going on. And if we want to reach the full potential of organizational life, it's important to recognize that truth. A business is a complex adaptive social system because it is more than the sum of its parts, but also because its parts are people—unruly, innovative, unpredictable, irrational, responsible, empathetic, intentional, creative, surprising people.

In fact, one of the things I love about business is that it represents the cutting edge of our capacity as human beings to join together, engage our best efforts, and improve our lives both individually and collectively. Business, as a shared endeavor, is a kind of evolutionary forefront in our cultural capacity to organize. Of course, humans are tribal creatures and we have always naturally come together and cooperated in small bands, and over the last several thousand years gathered together in larger cities. But larger organizational efforts have been more limited. Indeed, there was a time when the most dramatic and impressive examples of humans banding together in large collectives only happened in rare circumstances, usually through intensive government effort, religious solidarity, or out of military necessity. But over the past few hundred years, something remarkable has happened. Humans have begun to band together in an historically unprecedented way—to accomplish things through the domain of business. These extended tribes have arisen to accomplish all kinds of things together—to create and innovate, to build and scale, to produce and sell. Today's organizational entities go beyond business of course—there are many other examples of large and impressive organizations today, like nonprofits or educational institutions. But even so, business has truly been at the leading edge, and sometimes bleeding edge, of learning how to make human organization adaptive and dynamic even as it grows larger and more complex. Indeed, understanding how to make large organizations work in a dynamic way is still a relatively new science, and there is so much to learn. But make no mistake, our ability to solve tomorrow's great challenges will, in no small way, depend on our ability to effectively organize and accomplish things together at scale, in complex adaptive social systems.

In my experience, many business leaders don't think about any of this when they start a company, or even take over an established one. They focus their attention on creating or refining their value proposition, developing their product or services, finding customers, marketing, sales, and so forth. Then one day, they wake up and realize that they are in charge of much more than profit and loss statements. It dawns on them that they are holding the reins of a strange, unpredictable beast that has its own ideas, its own seeming agency, and can be quite resistant to outside input and to demands for change. Occasionally, the necessary leadership skills come naturally, and an entrepreneur or executive manages to navigate this task with instinct and intuition. But even the best instincts in the world only get you so far when it comes to something as complex as human systems.

I remember one painful situation in which thinking of teams and companies as mechanical systems, rather than social systems, led to a near disaster for a company, and a professional setback for me personally. The context was a recent merger of three large consumer products companies. The opportunity, as envisioned by the board of directors who had engineered the merger, was to increase the market potential of the enterprise and to reduce its overall costs by combining and streamlining the sales capabilities across the three companies.

After the transaction had been completed, they moved quickly to change the organizational structure, so that all the sales capabilities from across the three companies now reported to a single functional leader. I remember they gave that person the title of “Global Head of Sales” and he was appointed as the new enterprise leader. The board then directed the three former CEOs, who still had their CEO titles, and the new Global Head of Sales, to work as a team and align on a path forward for the company. As you might imagine, it easily turned into a battle zone, as the three CEOs competed for access to sales resources.

The board had been approaching the issue in mechanical terms, not social system ones. Thinking they could plug and play various leaders from a distance, they'd given little thought to what would make the social system of the combined businesses thrive. And in my role as consultant, I was tasked with aligning this team. Unfortunately, I had not yet embraced a deeper view of organizational life, nor fully understood the nature of the system I was working with. I wasn't yet approaching these issues from a social systems perspective. So I tried to simply convince the competing CEOs that I had a great plan. They resisted. I failed to recognize the social dynamics that were setting them on a path of conflict, and even more importantly, I failed to work with them to build relationships, understand their needs, and co-develop an organic path forward that could actually achieve alignment from the inside out. I was offering a monologue when a deeper dialogue was needed. But in those days, I didn't yet appreciate the transformative power of authentic conversations to influence social systems. As a result, I lost influence, and failed in my mission.

I've seen many business leaders reach the point when they begin to realize that leading an organizational social system is much more complex and difficult than they had bargained for. At that point, they sometimes start wishing that they could simply replace their team. Hire a new group of super-talented, easy-to-manage, uncomplicated team members who already work perfectly well together, and all the problems will simply vanish! But of course, that's not possible. Sometimes bringing in new blood is helpful, but the idea that the problems are rooted in having the wrong people as opposed to inadequate leadership and a dysfunctional organizational regime is the unfortunate root of many problems in today's workplace. I promise you, there is no perfect team out there on LinkedIn waiting to answer your email. Sooner or later, every successful leader has to grapple with a terrible but liberating truth—they can't solve their problems through hiring and firing. They have to find ways to develop their own leadership intelligence, which will then allow them to develop their team and ultimately influence their company. Thus begins the journey, and the real work of organizational transformation.

In most cases, the unpredictability of a complex adaptive social system only reveals itself under the pressures of change. The company may have been ticking along just fine for its first couple of years—small but profitable. It has systems and structures in place; established ways of working; and a well-developed business model for delivering its services. The team is tight, and they've been together since the beginning. They know how things work, and they know who has power and influence. They've learned how to get what they need to do their jobs. But then, one day, everything has to change.

The pressure of change can take many forms. Sometimes, it's good news, like a new market opportunity. Demand for the company's products or services takes off, and it suddenly needs to grow from a quirky startup into a larger enterprise. Sometimes, it's bad news. Competitive pressures in the industry render an existing business model ineffective, and the company realizes it needs to innovate new offerings or risk going out of business. Perhaps it acquires another company or is acquired. As the company begins to grapple with the demand for dramatic transformation, it quickly becomes clear that its old ways of doing things are not going to get it where it needs to go.

The particulars can vary, but it begins to become clear that the existing culture of the organization is faltering. Changes are needed, but aren't happening. Strategic shifts seem impossible. Cultural confusion escalates. People start acting strangely. They seem to agree with what's said in the meeting but then go away and do something different than what was agreed. The Swirl accelerates even as the need to transcend it becomes acute. Frustration grows. Indeed, it can feel as if the system itself is resisting the change. And the leader needs to figure out how to lead the system itself on the journey to higher performance.

Making the type of changes that can lead the organization out of the Swirl is never quick and easy. But here is the good news. It's not just about escaping what's wrong; it's also about discovering what's possible. And this requires a deeper understanding of how we view the organization we're trying to change. Indeed, if you truly want your business to reach its higher potentials, you're going to need to learn how to wield influence not just over individuals but over complex adaptive social systems. Change, in a complex adaptive social system, cannot really be “managed,” whatever consultants would like you to believe. It must be led, first through the development of team and company leaders, and then through the development of teams. But leadership of a social system is not a one-way street. As I learned with those three companies in the merger I mentioned earlier, it requires much more than a monologue, however uplifting or inspiring. It's a dialogue, a conversation—in fact, it requires a series of ongoing intentional conversations that have the power to align, reimagine, and consciously upgrade the social system. I've worked hard to refine these conversations into a series of Seven Crucial Conversations, a Growth River methodology that is essential to this upgrade and to building high-performing teams. They also inspired the title of this book. But before exploring these conversations in the second half of the book, there is much I need to convey about social systems, the nature of a business, growth and transformation, the evolutionary stages of an enterprise, and the latent potentials that are embedded in organizational social systems, even those that are mired in the Swirl.

I used the word consciously earlier, and it's an important term to pause and reflect on. There comes a point in the evolution of an enterprise when change must be consciously engaged. And that requires leadership. Otherwise, the inertia, good or bad, of the existing culture dominates. Indeed, one way to think about the culture is that it's what people do when no one is telling them what to do. That's unconscious or natural culture—the natural pattern of the social system when it is undirected, when people are filling the void and choosing how to behave in the absence of leadership. That may be positive, negative, or otherwise, but when you reach a point where you need to upgrade, shift, or evolve the complex adaptive social system of your organizations, make no mistake, leadership will be essential. It takes leadership to create a more conscious or intentional culture, one in which the ways of thinking and acting are purposefully aligned at a higher level of performance.

Leading Social Systems versus Leading Mechanical Systems

Again, a leadership style is shaped by how the leader sees the system they are working in. If you view your organization as a mechanical system made up of parts, inputs, and outputs, you'll lead it one way. If you view it as a social system composed of people playing their roles, forming relationships with others, exercising their agency to negotiate shared purpose and ways of working in the context of those relationships, you'll lead it another way. The social systems view includes the process flow of inputs and outputs between roles in the system but goes beyond it to take into consideration the human aspect of those interdependencies as well.

In the mechanical systems view, solutions are designed top-down and team members are expected to follow the directives set forth as tasks, processes, and project plans. In this view, some roles are assigned strategic planning responsibilities, and others are expected to execute. Conversely, when operating from the social systems view, all roles are expected to engage and contribute their perspective to the overall strategy. Solutions may still be designed top-down but validated and updated based on bottom-up feedback, and in the context of aligning purpose, roles, and ways of working. In this view, all players are empowered to exercise their agency and choice, and leaders need to align team members around their decisions through communication and consultation.

Although both perspectives have their advantages, the journey of growth and transformation that I'm describing in these pages can only occur if all team members fully embrace the implications of a social systems perspective, as a necessary condition for reaching higher levels of team and organizational performance.

The following are a few key characteristics of the social system mindset as contrasted with the mechanical system mindset:

- Interpersonal, not impersonal: Leaders focus on influencing others and creating alignment through conversation, rather than relying on the weight of hierarchical authority.

- Relational, not transactional: Leaders focus on building and maintaining strong mutual relationships, rather than supervising outputs.

- Inclusive, not exclusive: Leaders focus on ensuring everyone on the team has agency and choice and is fully engaged in the transformation process.

The Art of Alignment

Let's return to that swirling, tumbling river we were navigating earlier in these pages. As you steer your team and organizational watercraft through the rapids of changing markets, around your competitors, avoiding the rocks, and riding the currents, the last thing you need is for all the people on board to be rowing in different directions. You need them to be aligned. You need them to be working for a common purpose, pointing in the same direction—the direction of growth and higher performance.

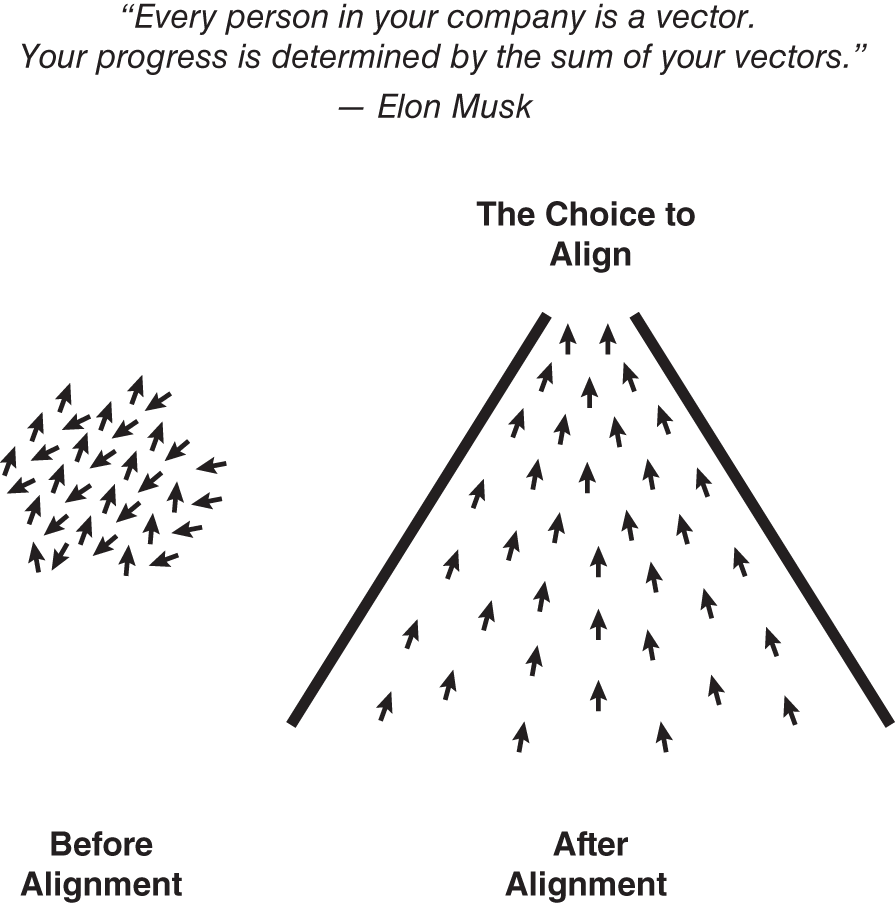

If the river is calm and the current steady, it can feel like it is less important for everyone to work in a closely aligned way. Some might be rowing faster, some slower. Some might be taking a break and watching the scenery pass by. A few strong arms can keep the boat on course. But as the river gets rougher, with more obstacles, rapids, and eddies, you need all hands on deck. The more complex a system becomes, the more critical alignment is. In any system, there are multiple parts that are in motion, and the overall success of the system is the sum total of those parts aligning in the same direction. In a simple system with just a few parts, some semblance of alignment might be achieved with top-down authority, but it's really just compliance. Once the system grows in complexity, that simply doesn't work. A top-down controlled system will never be able to adapt quickly enough to the changing environment, nor will it harness the creativity and potential that is inherent in its many parts. You're treating people like parts in a machine, and the best that mechanical parts can do is not break down. They can't transform, evolve, or innovate. But if you respect that the parts are free-thinking, creative human beings who make their own choices about how to use their time and energy, you have to take a different approach. Sure, you could enforce compliance, but you recognize that that will never add up to truly high performance. The job of leadership is to create alignment, which is different than creating agreement. That difference is critical. Alignment requires that the individuals choose to move in the direction of growth. People can agree, disagree, or anything in between, but they can still independently align and move forward, and that makes all the difference. They don't simply go through the motions; they actively contribute. People who are merely complying feel victimized, and that state of mind is never conducive to high performance. Alignment is a free choice that liberates innovation and intelligence. See Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 The Art of Aligning People as Vectors

To achieve alignment in a complex adaptive social system, leaders must become skilled at breaking complex issues down to the key choice points. These are the moments when people need to consciously choose to come along on the journey together, and the leader's job is to initiate the conversations that lead to those choices. These are the seven “crucial conversations” that we will delve into more deeply in the third section of this book. They are an essential part of the Growth River Operating System. Out of these conversations, people can come to a choice about what's right for the team and decide upon and implement shared ways of working. There is no subterfuge or sleight of hand involved in obtaining alignment. That would defeat the purpose. These are conversations that are held transparently and openly. Suffice to say again that we're not talking about requiring every individual to perfectly agree with or even like the decisions that are made, but we are talking about every individual recognizing those decisions to be in the best interests of the team or organization. Therefore, they'll choose to put that above their own preferences or opinions.

Unless a leader respects people's agency, and skillfully creates the choice points at which they can align, the result will never be transformation in the team or organization. But this way of thinking is counterintuitive. People often think that they can grow faster if they drive choice out of the system. When you're caught in the Swirl, the last thing you feel like doing is inviting more input, opinions, and perspectives into the conversation. That brings about a level of complexity that some leaders find unbearable. They want to “nail and scale” their business models and their systems, so that they run like a well-oiled machine. It may even work for a period of time, so long as the waters are calm and the currents predictable. It may even be appropriate at certain points in the organization's journey. But here's the issue. Without knowing it, they have created a culture with so little tolerance for diversity that it can't handle complexity. As soon as they hit a certain level of complexity, or unexpected events throw them off balance, it becomes difficult to function. By driving choice and agency out of the system for all but the top leadership, they have lowered their own potential as an organization to adapt, to be creative, to pivot, and ultimately to grow and thrive over the long term. If you want to get out of the Swirl, you don't do so by shutting down the conversation; you do so by accelerating the clarity of the conversation, which means getting to alignment.

That is what the Growth River Operating System allows you to do—create alignment and lead transformation in complex adaptive social systems. “Operating System” may sound like it's straight out of the old machine metaphor I've just advised you to leave behind. But it's not software I'm talking about; it's “social-ware.” social-ware means a system for working together in a social system that enables higher performance. It is an upgrade for the human system in the same way that software can be an upgrade for a computer system. Again, it's not simple, because human systems are not simple. It's not a quick fix, because adaptation and evolution doesn't happen quickly. But it is elegant, creative, uplifting, and powerful, because at their best, human systems are all of those things.