CHAPTER 3

Understanding Growth: Dynamics of Organizational Development

One can choose to go back toward safety or forward toward growth. Growth must be chosen again and again; fear must be overcome again and again.

—Abraham Maslow

What does growth mean? In business, the term is used in many different ways. Broadly speaking, it means the business is expanding and improving—perhaps in terms of revenue or profit, perhaps in its number of employees or customers, perhaps in its physical footprint, perhaps in its range of products or services, perhaps in its value as a company. All these are metrics that businesses use to define and quantify growth. Growth can be slow and steady, or it can come in a sudden surge. Sometimes, if growth happens too fast, it proves to be unsustainable. As we've discussed, a business is more than its physical metrics, and if growth is to be sustained, it must become established in the social system. For an organization to grow and thrive, we must consider what “growth” means for that whole system, and how it can be skillfully led.

To take a simple analogy, think of the organization as a child. If you're a parent, you want that child to grow up in the healthiest way possible—to progress in physical, emotional, and intellectual maturity. And most of us, whether we're parents ourselves or not, have a sense of what a child needs at various points in the life cycle. We intuitively know that certain conditions are nurturing and supportive, whereas others might be destabilizing and even damaging. Of course, parenting is far from a perfect science, and growth is not a linear or simple process—it's an interwoven, unfolding set of dynamics with all kinds of complexities involved. But the more a parent understands and recognizes those, the more they can guide, encourage, and support the child's growth. In the same way, the leader of a growing company needs to understand the dynamics of organizational growth, the stages through which it passes, the different needs and challenges of each stage, the constraints it might encounter, and so on.

Growth in an organization—just like growth in a child—has a natural pathway and order. Don't fight that flow. Part of the job of a leader is to understand it better, and in so doing find ways to support and encourage it. You don't need to reengineer the child; you just need to give them optimal conditions, support, and protection. And one of the most important accelerators of growth is that simple awareness: when everyone in an organization, from the leader on down, begins to understand the dynamics of development and to think developmentally—about their own roles and about the organization as a whole.

Over the years, I've watched hundreds of organizations, large and small, navigate the journey of growth—from tech startups to national retail chains, from wealth management firms to healthcare systems. In many ways, each journey is unique—the people are different, the customers vary, the products and services are specific to each market. Some are public companies; some are private. Some are for-profit and some are nonprofit. Some are complex enterprises with numerous business lines; others are streamlined specialists with a single offering. But as I observed, and participated in, these disparate journeys, what caught my attention were not the differences but the remarkable similarities. While many aspects of the growth journey are particular to the business involved, the overall trajectory is in fact quite consistent. If you step back from the details of each organization, the path they follow has the same general structure. It includes the same fundamental milestones; it encounters similar breakdowns and breakthroughs; and it leads to the same general destination. Indeed, amidst all of the tremendous variation in the business landscape, there is a game-changing truth that is easy to miss: The journey of organizational growth and scale passes through a series of stages that are common to every traveler.

Growth Moves Through Stages

To help illustrate what I mean by “stages,” let's continue with the childhood analogy—since it's a journey that you've certainly experienced personally and may also have observed up close if you're a parent. Every human baby embarks on a journey of growth and development—from infant to toddler to child to adolescent and finally to adulthood. Most people would agree that in this process, children pass through recognizable stages that they then outgrow, moving on to the next. Life stage transitions are not only predictable—they are predicted. This doesn't mean all children are the same, or that they all move through the stages of maturation at the same speed. Indeed, any parent will tell you that no two children develop in exactly the same way, and that the ages at which they reach certain milestones like talking, walking, or puberty may differ quite widely, even within a family. But nevertheless, the stages through which they pass are clearly identifiable. They follow an inexorable developmental logic.

This probably seems obvious to most, but it wasn't always recognized clearly. In fact, before the early twentieth century, there was a general tendency to think of children as simply having less knowledge than adults. Their bodies were obviously growing and changing, but it wasn't understood that their psychology, their ways of organizing reality, and their capacities to process their experiences were also developing. It was the pioneering psychologist James Mark Baldwin who first proposed, after observing his own daughter, that children pass through a specific series of developmental stages on their journey to adulthood. This idea was further advanced by the great developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, and today it's become so widely accepted that many of us don't even realize that human beings ever thought differently.

I'd suggest that this is as true when it comes to organizations as to people. Just as a child is not simply a little adult, a startup is not just a smaller company than a global enterprise. It's a less developed company. And the journey from one to the other doesn't just involve increasing headcount, square footage, assets, production levels, or revenue. It involves developing and maturing through a series of essential stages that are as predictable and consistent as infancy, toddlerhood, and adolescence. At each change, the organization must fundamentally reinvent how it sees itself, how it organizes itself, and how it interacts with its stakeholders. In Part II of this book, I'll give an overview of what I call the four stages of enterprise evolution, and then we'll take a journey inside the evolutionary process as a company moves through each. But first, there are a few more fundamentals to be covered about the dynamics of organizational growth.

Growth Happens in Three Domains

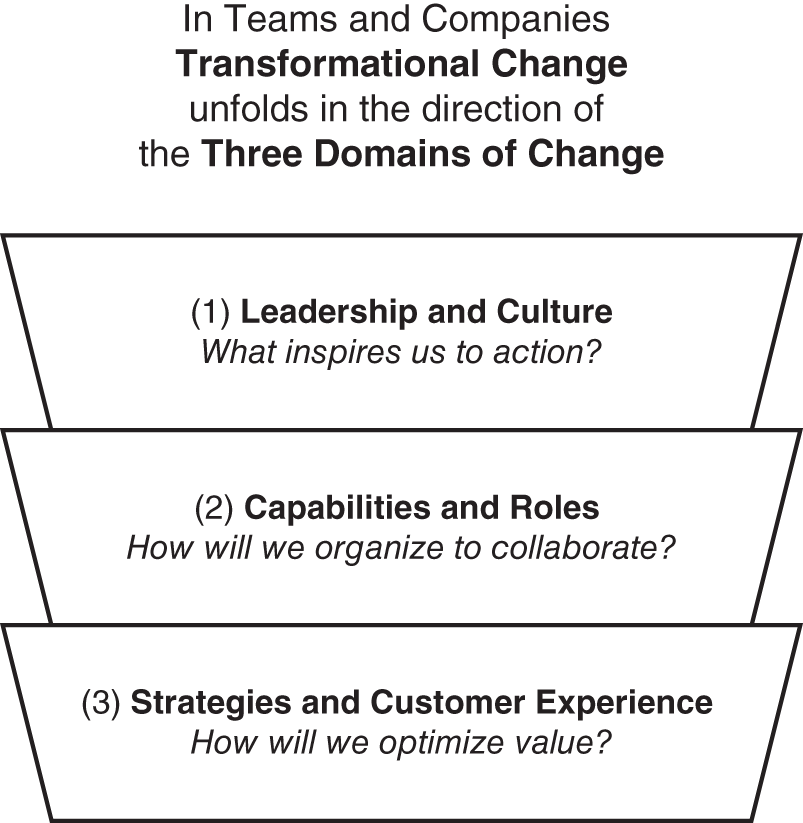

When you're trying to effectuate growth, the question inevitably arises: what exactly needs to change? No doubt, you'll come up with a list of dozens of things, large and small. Is it the structure of the organization? Its leadership? Its focus? Its operational processes? Its business model? Perhaps it's all the above, and more. Moving your organization to a new stage in its development will likely involve multiple shifts—just as a child moving from infancy into toddlerhood develops in body, mind, heart, and soul. Remember, what's growing is not an object like a machine, but a system—a complex adaptive social system that has formed to create value through one or more Business Triangles. So very quickly, you have a new question: What needs to change first? You may know that you want to grow, to transform your team and your organization, but where should you start? It's important to have a method for discerning the right sequence for implementing changes—for knowing which breakthroughs to aim for, in what order, and being intentional about it. Some years ago, I visited the Inca temples in Peru, and it struck me how the bottom of each wall was made up of great big blocks, which got smaller as they moved up the wall. It seemed an apt analogy for the process of organizational change. Which are the big blocks that have to go on the bottom? If you start with all the little ones and then try to balance the big one on top, your wall is likely to fall down. You risk destabilizing the system, creating waste, and causing confusion and resistance. The right sequence will unlock the potential for growth of the business as a social system, the potential for people to fully engage together, whereas the wrong sequence might give you the short-term deliverables that you seek but not the growth potential. I refer to this as a natural developmental path. As a general rule, I've come to recognize that successful change initiatives that move an organization to a new stage need to unfold through three domains of change, in the sequence shown in Figure 3.1.

The transformation begins with Leadership and Culture, where a deeper understanding needs to take root and be shared. Leadership and cultural agility are the launch pad for all successful transformational change journeys. High-performing teams and organizations work to get leadership and culture right before diving into the content of roles, strategies, tactics, and execution. The old business adage “culture eats strategy for breakfast” speaks directly to this point. Put another way, a great strategy in an ineffective culture is worth less than a mediocre strategy in a learning culture.

FIGURE 3.1 Transformational Change and the Three Domains of Change

Once the change is established in the domain of Leadership and Culture, it can unfold into Capabilities and Roles, playing out in the behaviors of each individual as they relate to the collective. Capabilities and Roles essentially means that it is critical to get the right people doing the right jobs with the right visibility, responsibility, and accountability. And once these are in place, the change can spill over into Strategies and Customer Experience, accelerating the company's ability to develop, sell, and deliver its product or service and increasing its competitive advantage. It sounds simple, and in a sense, it is. But, actually enacting this cascade of transformation though these domains of change takes great skill and awareness.

Change management initiatives that try to bypass this natural order of unfolding are rarely successful. If you jump straight to strategy before the new forms of leadership and culture are established, you'll lose people's trust very quickly, creating a veneer of compliance but not real engagement. Ultimately, such initiatives lead to change fatigue. Remember, these are human systems, not machines. Human beings have agency. It's a game of choice, not compliance. That doesn't mean everything must be run by consensus, but it does mean that people need to be offered choices, and incentives, to align with the overall direction of growth and high performance.

Likewise, if you jump to strategies and customer experience before you have fully implemented a functional workable system of capabilities and roles, you will likely find those initiatives stymied and undercut.

In Part II of this book, as we explore how the journey of growth looks and feels in more detail, you'll see change playing out in all of these three domains at each stage in the enterprise's evolution. And when we turn to the Seven Crucial Conversations in Part III, you'll see that they are specifically designed to guide a team through these three domains, in sequence. Of course, transformation is not as simple as one-two-three-and-done, because organizations are layered and complex. But in broad strokes, at each level, whether it be a single team, a small business, or a large enterprise, you'll see how the natural path of transformation flows from leadership and culture, through capabilities and roles, and on into strategies and customer experience. Following this sequence unlocks the potential for long-term, sustainable growth in the entire social system.

What Limits Growth? Understanding Constraints

The analogy between organizational growth and childhood development is helpful, but it only goes so far. When it comes to organizations, the fact that stages of development exist does not mean they are inevitable. Indeed, unlike the biological and psychological journey of babies growing into adults, an organization's evolutionary journey cannot be taken for granted. All organizations may encounter the same pressures and problems sooner or later, but as complex adaptive social systems, they have to choose and align to take the next step.

Yes, I believe that the stages represent a natural developmental path. In other words, they are not a system we impose on an organization or a senior leadership team so much as a pattern that emerges organically as an organization evolves, once constraints to its growth are removed. They involve a series of challenges and breakthroughs that companies can be expected to experience as they develop. In many companies, these stages will unfold all by themselves, over years or even decades. However, progress through these stages isn't a given. It is all too easy for arrested development to occur. An organization can get stuck at one stage or fail to see the potential that awaits it on the other side of an entrenched status quo.

Why do organizations get stuck? Growth occurs naturally in most systems, when the conditions are right. If growth stops, it's because something is blocking its path, like a logjam in the river. When debris piles up, the forward-rushing flow of water may be reduced to a trickle. Stagnant pools form, and things settle into stasis. The same happens in an organizational system. Growth is happening, production lines are flowing, customers are buying, revenue is increasing, the organization scales up in response, and then at some point, it slows, or stagnates. Sometimes, the reason is obvious. Changes in the competitive landscape. Location issues. Infrastructure. Personnel. Other times, it can be hard to pinpoint where exactly things got stuck.

In the business world, the sticking point in a system is often called a constraint. The term comes from the work of Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt, who shared it in a hugely popular 1984 business novel entitled The Goal. The essential insight of constraint theory is that in any given system there will be one key limiting factor that stands in the way of the system growing, improving, and achieving its goals. This is known as the primary constraint. Sometimes the constraint is obvious; other times it's hidden. Sometimes it's unchangeable, in which case all you can do is optimize around it. However, if you can identify and remove or resolve the primary constraint, a system will transform and move to a higher level of growth. Figure 3.2 shows a system resolve its primary constraints and break through to higher performance levels.

Goldratt used a manufacturing scenario to illustrate this idea, showing how removing bottlenecks in a production process increases efficiency and throughput (see Figure 3.3). But it is equally true in any system. “Since the strength of the chain is determined by the weakest link, then the first step to improve an organization must be to identify the weakest link,” he writes.1

A simple example of a primary constraint in a manufacturing environment might be a certain type of machine. If the machine is only capable of producing 10 items every hour, that will always limit your capacity to deliver your products. You might try to change other things—hiring more people to speed up other parts of the system, moving your factory to a better location, improving your delivery processes to ensure fast delivery to customers. These changes will make some difference, but the essential bottleneck remains in place. But if you can increase the capacity of that machine by, for example, purchasing more machines or getting a better machine, you could resolve the primary constraint in the system, and the business could grow exponentially.

The Theory of Constraints, as Goldratt initially conceived it, was aimed primarily at optimizing manufacturing processes, not transforming organizations as a whole. But it is also a powerful way to think about growing and scaling companies because it can focus leadership teams on the the highest leverage point for transformation. Identifying and resolving constraints is the fastest path to high performance. You can change and optimize all kinds of factors in a system and not fundamentally impact its potential for growth. But if you can identify and resolve the primary constraint, growth will occur, even if there are many other areas that could still use improvement. This is what we call a breakthrough, because it moves the whole system to a sustainable higher level of performance. When a primary constraint is resolved, sooner or later another will reveal itself. At that point, the higher level has become a plateau, and to go to the next level, you need a different approach than whatever led to your last.

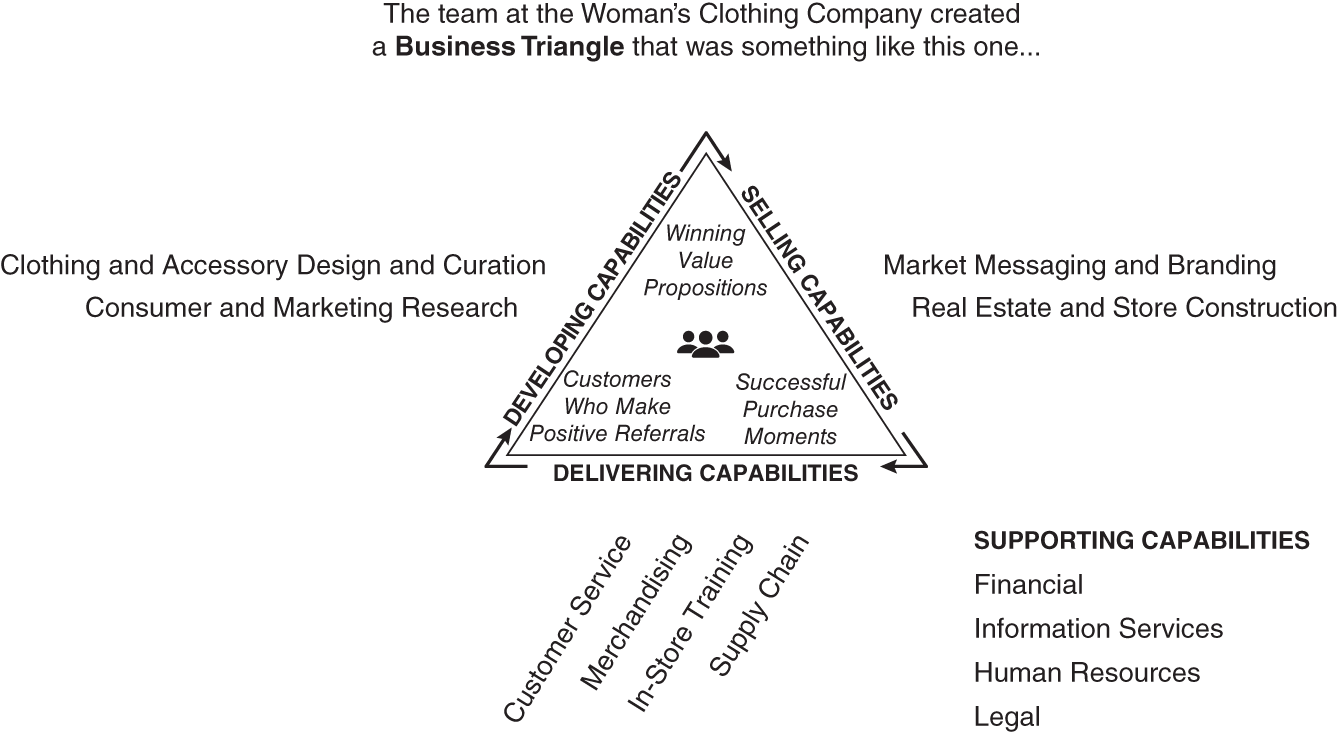

Some years ago, I was brought in to consult with the leadership team at a national women's clothing retail chain. The company had been founded in the early 1980s in a small gallery on a Gulf Coast Island that was popular with tourists. The founder worked in close collaboration with his vendors and channel partners to create a winning customer experience. They sold unique pieces designed and curated to inspire women to feel good (no matter their age) and to help them express their personality and individuality with confidence. He had nailed his value proposition and the next step was to scale it, which he did, building a business team to fill out the capabilities around the Business Triangle. Figure 3.4 shows a simplified example of how that looked.

FIGURE 3.4 Example Capabilities Mapping Around the Business Triangle

Their aim was simple: to open and support as many retail stores as possible, capitalizing on the winning customer experience. Their primary constraint was on the Sell side of the triangle: it was the speed at which they could open those stores. Put another way, the company could grow as fast as it could open stores to sell and deliver.

And it did. It went public and scaled over the next couple of decades to have over a thousand stores. It hired the best lawyers and real estate experts and effectively removed that constraint to growth. It was so successful that at one time it had the highest sales per square foot of retail space in the industry. But by the time I arrived to work with the enterprise team, things weren't looking so bright. Same-store sales had been declining week-over-week for almost a year, and the company's stock price was in a tailspin.

At our first offsite meeting, I introduced the Business Triangle, and in short order it was clear that the primary constraint had shifted. It was no longer on the Sell side—opening new stores faster wouldn't help them grow. It was on the Develop side. They needed to make significant changes to their value proposition, rethinking the store concept in light of changing fashion trends and changing consumer behavior and increased competition.

As I looked into team members' eyes, I could tell this was not new news. They already knew that their primary constraint had shifted. So, why were they stuck? The challenge, I learned, was that no one on the senior leadership team, not even the CEO, had a license to make significant changes to the founder's original formula. The founder was the majority shareholder, he controlled the board of directors, he had chosen the current CEO, and he had not given him the authority to make those kinds of changes.

Over the next day and a half, the team openly discussed various dimensions of the challenge. They made commitments to stick it out together. And they reached initial alignment on a plan. This was a smart and experienced group of business leaders that was pulling together to do whatever they needed to do to win as a team. The CEO agreed to meet with the founder and make the case for having the decision rights that he needed to lead the transformation. Other team members would draft the plan for rethinking the core brand experience. In private back-channel discussions between the CEO, the CFO, and me, the CEO framed out how he might want to reconfigure the membership of his enterprise team, adding more representation from the Develop side. He thought that one particular person should be promoted to enterprise team. In addition, he warned, the company would likely need to pause plans for opening new stores, at least until same-store sales could be aimed in a positive direction. After a day and a half of intense work, the team atmosphere still felt a little nervous but also much more hopeful.

Unfortunately, though we had identified the new constraint and a way forward, the existing social system would prove intransigent. We had agreed to meet again in a month, but the meeting got postponed, and then postponed again. Finally, when two months had passed, I arrived for our session, only to discover that no progress had been made toward resolving the constraint. The founder had remained adamant that his formula was not to be changed. What had they been doing for two whole months, I wondered? Well, it turned out they'd been doing something: they'd opened more than 50 new stores! They'd reverted to doing what they were good at, unable to deal with the fact that the constraint had moved and something different was required if they were to grow.

Constraints theory is a powerful tool for revealing what needs to happen in a business to reach the next level of performance and growth. But organizations, as we've seen, are not machines or even assembly lines. To resolve the constraint in such a way that propelled them to a high level of growth, the company would have needed to engage with the difficult human dynamics embedded in its social system. I worked with the team for a few more months, but the writing was on the wall. Not much later the CEO and other senior leaders began to leave the company.

Two Types of Performance Improvement: Horizontal and Vertical

Understanding constraints leads us to one final distinction that is critical to understanding the dynamics of growth. There are fundamentally two different ways to think about performance improvement in any kind of system: horizontal and vertical. Put simply, horizontal improvement means that you optimize within the constraints of the current system. You don't try to remove or resolve the primary constraint, but you do everything you can to perform better with the constraint in place. Vertical performance improvement occurs when you resolve a primary constraint. A breakthrough occurs where you find yourself in a different landscape. It's the domain of innovation and transformation.

A classic example of the two perspectives is a railway company. Horizontal improvement is about having the trains run more on time—cutting costs, improving processes, streamlining operations. You know the rails you're running on, but you can make the train more efficient and predictable. Vertical improvement, on the other hand, is like laying new tracks that take your train to a new destination.

All that being said, both horizontal and vertical are important modes of change. Both are necessary for a company to thrive. It's not an either/or situation; nor is one better than the other. Transformational growth in an organizational system requires both. If you only focus on horizontal change, sooner or later your system will stagnate. You'll eliminate all the inefficiencies from the system, but because you're not tackling the primary constraint, sooner or later you'll reach the limits of optimization. You see this often in companies that are really good at one thing—for example, maybe they have a sophisticated production process, or a great marketing team—but they have little capacity to innovate beyond that singular strength. Horizontal change is rarely adequate to meet the demands of long-term development and growth. However, it is necessary. If you focus only on vertical change, you'll neglect the important work of stabilizing your processes, becoming more efficient, and keeping costs down. Entrepreneurs are often likely to err on this side of the equation, because their natural inclination is to innovate, not to manage.

Managing the delicate balance of vertical and horizontal is a task every leader must embrace. And it's not possible unless you know where the constraints lie in your system. Sometimes, once you recognize a constraint, you might decide it's a positive check on the system. I'm part owner of a baked goods company that makes vegan minimuffins. We've created a very efficient production system, but the speed at which we can produce our minimuffins is constrained by how fast we can mix the batter. The mixing bowls are our primary constraint—and we've decided that's a good thing. It gives us a point of control in the system, which helps us to ensure quality and control work in progress.

When it comes to horizontal change, there's plenty of great advice to be found and systems you can adopt. Approaches like Six Sigma and OpEx can help you optimize within the limits of your current system. When it comes to vertical change, that's a greater challenge. Approaches like Agile, Lean, or Design Thinking can help you consider what vertical change might look like at the level of processes and operations. In that respect, they can be quite powerful. Growth River and the Seven Crucial Conversations are designed to enact vertical change at the level of the social system itself. Upgrading the “social-ware” of an organization—resolving constraints at that level—is a unique and powerful type of transformation. It can move your entire organization—its leadership and culture; its capabilities and roles; its strategies and implementation—to a new developmental stage, reflected in a new structure and operating model that tell a whole new story about who you are and why you exist. Are you ready to experience the four-stage journey of enterprise evolution? Let's begin …

Note

- 1 Eliyahu M. Goldratt, The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement, 3rd ed. (Great Barrington, MA: North Rover Press, 2004).