Chapter 6

The Components of Security Culture

Concerning the challenge we just faced about how to describe things in numbers and definitions, that is the reason for a unity/oneness? For however many things have a plurality of parts and are not merely a complete aggregate but instead some kind of a whole beyond its parts.

Aristotle

The security industry has struggled to define security culture for a long time. Security leaders talk about the value of security culture; but, as we've mentioned previously, they tend to do so without precision. This chapter is about adding that needed precision. Specifically, we'll take a deep dive into seven components that together comprise security culture. This is our perspective, developed over many years at the intersection of two worlds: academia and the “in the trenches” practitioners.

Understanding that security culture is composed of these seven components (which we refer to as dimensions) is useful. It brings precision and gives us something to observe and measure. We'll also discuss actions that can be taken to manage the security culture of an organization or group by influencing one or more of the components.

A Problem of Definition

Anyone who decides to study security culture will quickly notice something interesting: They discover that nobody seems to agree what this thing we call security culture is. There seems to be as many definitions of security culture as there are academic papers on the topic. To make matters worse, very few of the proposed definitions can offer a holistic overview; instead, you are either given fuzzy generalities or are offered a subset of what culture may consist of.

The Academic Perspective

Academic research follows high standards that often require peer review, ethics reviews, and usually focuses on granular detail. This is great when it comes to understanding the nuances and the different impacts that certain behavioral interventions, training messages, or other tactics may have. It is also extremely helpful when examining isolated elements and their relation to other elements of culture. The challenge, though, is that most academic research is very narrowly focused. It only tells a small part of the story, leaving the rest to interpretation or to be tackled in a later study.

Another challenge is that academics from a wide range of scientific fields of study—from computer scientists to psychologists, and from organizational theorists to economists, to name just a few—are looking into security culture from their own perspective without communicating and sharing their learning across the different fields. This means that the growing body of research is fragmented and difficult to follow, and that sometimes the debate feels more like a turf-war than a mutual interest in furthering the field of research.

The upside is that security culture is being researched from all these different angles, which will be extremely helpful to anyone willing to assemble learnings from across all these disciplines.

The final challenge with academic research is the lack of distribution outside of academic circles.

The Practitioner Perspective

Practitioners in our industry agree that security culture is a vital component of their cybersecurity program. As we mentioned in Chapter 1, however, research shows that security practitioners have difficulty agreeing on what security culture is. This may be because the phrase security culture is rather new, leading to some confusion. Our industry has talked about security awareness for a long time, leading to some security people thinking security culture is just awareness with a new name. Another bias we see, particularly in some industries where safety is key to success, is a definition of security culture as though it is safety culture: dealing with the physical world instead of the abstracted world of information. It is much easier for us as humans to understand how a hard hat will protect our head from falling debris versus understanding how sharing our credentials in a phishing scam can injure us and our employer.

Talk of security culture is sometimes met with skepticism. Is it not only smoke and mirrors? Is it just awareness rebranded? This skepticism is warranted. We've seen smoke-and-mirror security culture marketing before. But, thankfully, we've recently seen the market offering a bit more substance. That's encouraging. Some of this might even be due to our own efforts in this space, such as Kai's creation of the Security Culture Framework and the Security Culture Survey (which we'll be covering in the next few chapters), Perry's research and writing around awareness, behavior, and culture, and Kai's research into seven specific dimensions of security culture.

Understanding that security culture is really a combination of several observable and measurable components (or dimensions) is fundamental to finding ways to intentionally influence and improve security culture.

This understanding also allows for clear reporting to executive teams, boards of directors, employees, and more. In fact, these seven dimensions of security culture and the Security Culture Survey form the foundation of another of Kai's efforts: the annual Security Culture Report.

Defining Security Culture

Our current working definition of security culture is as follows:

- Security culture is the ideas, customs, and social behaviors of a group that influence its security.

Any culture is the codification of the beliefs, behaviors, and values of a particular people group. So, when you add a security context, you see that a security culture is the codification of everything security-related or security-impacting as it relates to beliefs, behaviors, and values. This perspective is based on a sociological understanding of culture and is useful as a foundation to create a common understanding of what security culture is:

- Ideas: Includes values and shared mental patterns, as well as the shared understanding of what is acceptable and not.

- Customs: Accounts for the habits and automatic behaviors that are part of the groups' accepted norms, as well as those that are not. They are considered customs because of their automatic and assumed nature.

- Social behaviors: Describes the fact that each member of the group is constantly adjusting their behaviors to those acceptable by the group.

This definition may need to be amended in the future, but it gives us everything we need to have a meaningful discussion. However, as Gregor Petrič, PhD, patiently explained in 2015, “This definition is not good enough to allow a scientific measurement instrument to be built. We need a better one.” By better, it turned out, he meant a much narrower, more detail-focused definition. That new, narrower, and more detail-focused definition allowed Kai and Gregor to create the first commercially available scientific instrument for measuring security culture.

Security Culture as Dimensions

From a research perspective, we define security culture as a set of seven interdependent dimensions that together capture the phenomenon that we call security culture. Each dimension is found in academic research geared toward the study and measurement of culture from a sociological perspective. As of this writing, our research suggests that these seven dimensions are the most influential cultural elements related to security.1 Culture is more than just these seven dimensions, and your perspective will often determine which other elements you want to include in your own studies.

Each of the dimensions influences the other dimensions, creating a multitude of layers of influence, both direct and indirect. This complexity is supported by other research in the field—for example, the knowledge-attitude-behavior model proposed by Stephen Allen Robert (Roberts, 2020). This complexity may initially feel overwhelming, but trust us, it pays off. If you want to measure and influence culture, then you need the precision offered by this kind of model.

The Seven Dimensions of Security Culture

The seven dimensions of security culture are interdependent. Each one influences the others. This section offers a brief description of what each dimension captures. In Part III of this book, “Transformation,” we will explore how you can use these seven dimensions (and other levers) to improve your security culture.

Attitudes

The attitudes employees have toward security is a critical factor. If employees are negative toward security, they are much less likely to abide by the rules and to act securely. For example, research has shown that the best predictor of behaviors is not knowledge (training) but the employee's attitudes toward security. This means that finding ways to foster positive attitudes toward security can be a great strategy to improve behavior.

Behaviors

What employees see other employees do is very impactful on their own behavior. Most people are likely to adopt the behaviors that they see modeled by others when they are in a group. We are also very likely to do what we are told by someone in authority, suggesting that leadership should be actively involved in security.

Cognition

What employees know can influence their behavior. However, just because someone is aware doesn't mean that they care! And even caring doesn't always translate to behavior. This is what Perry calls the “knowledge-intention-behavior gap.” Training is an important part of any security culture program, but it is not the end-all. Instead, consider training as only one of many tools in your toolbox. Support it with strong messaging from the executives and leadership, and make sure the employees understand why security is paramount. Further support your training program through behavior design initiatives and by trying to foster other areas of influence, such as reward and reinforcement systems.

Communication

One of the skills of great leaders is their ability to communicate. Often you will hear them repeat the same vision many times over, in many different forms and forums. Great leaders recognize the importance of setting the agenda and repeating the message so that every employee can understand and relate. Security is no different: If you want it to happen, repeat your values often and find ways to make people talk about it.

Compliance

Organizations need rules to ensure that employees know what is allowed and what is not. Some organizations are very good at implementing policies and incentives, whereas others are not. If your security policies and procedures are not being followed, it may be because employees are unaware of the policies and procedures, or your policies and procedures are too difficult to follow, or because you need other methods and systems to support compliance.

Norms

Norms are the informal rules, those policies of the group that are not written down and formalized. Some norms may contradict policies. People are more likely to follow norms than complying with policies due to perceived peer pressure. Norms in your organization are “just the way things are done around here.” Seek out any disconnects between your norms and your policies. Find ways to influence your norms to better align with policy. This is accomplished through a combination of communication, social pressures, behavior design, and traditional training methods.

Responsibilities

An organization where every employee actively takes part in the security program is a good organization. Empowering employees to make relevant security decisions in their workday is a valuable strategy. Likewise, making sure employees understand that even a tiny action can make a huge difference will be important. Try to focus on the positive change the employee can make instead of dreaded and ineffective fearmongering.

The Security Culture Survey

As mentioned previously, one specific application for the seven dimensions is in the Security Culture Survey (KnowBe4, 2022). The Security Culture Survey applies these seven dimensions to measure security culture. Results are reported across each dimension, giving a comprehensive view of the state of an organization's security culture.

A critical goal of measuring culture is to get a picture that is as honest as possible. In other words, we must avoid asking questions that employees will be tempted to answer in ways that they believe will make them look good. Therefore, the Security Culture Survey was created to ask what employees see other employees do or what seems to be considered acceptable values and behaviors in their organization.

When you are working to improve security culture, you want the information you use to have the correct perspective. Knowledge and behaviors should be measured at an individual level to identify where weak spots and strong points are located. Sometimes there is an employee or group who has a specific behavior or lacks certain knowledge. Identifying those specific employees and groups will help you address problem areas as well as celebrate and reinforce strong areas.

In addition to gaining this knowledge about specific employees, you need to be able to zoom out. You want a broad perspective. Culture is about the group, whereas individuals are part of the group. You can most accurately measure the group perspective by asking about people's observations and perceptions of the organization, not about what they (as individuals) know or do. You want to ask what employees see other employees do, not what they tell you they do themselves.

Compared to how you tackle knowledge and behaviors, working with culture requires a broader set of tools and controls. These would include tools often associated with organizational culture management, communication strategies, training, support teams, and even technology-based support tools. We'll discuss these strategies for influencing culture more in Chapters 8, 10, and 12.

Influencing culture is about understanding the interplay between the dimensions.

And it's about understanding the interplay between people, process, and technology. Changing one facet will both directly and indirectly influence the other facets. You need to be aware of this. Understand where you are and where you want to go. Build your hypothesis. Then test and measure your results.

Example Findings from Measuring the Seven Dimensions

Here are a couple findings from our recent research. Because we collect data using the same set of items across thousands of organizations around the world, we are able to understand regional differences in security.

Normalized Use of Unauthorized Services

Employee use of unauthorized services, often referred to as shadow IT, poses a threat to organizations on many levels. Traditionally, it has been difficult to measure this phenomenon, usually because employees are not very likely to admit to breaking the company rules. The Security Culture Survey circumvents this bias, giving us a unique peek into how large a problem shadow IT is.

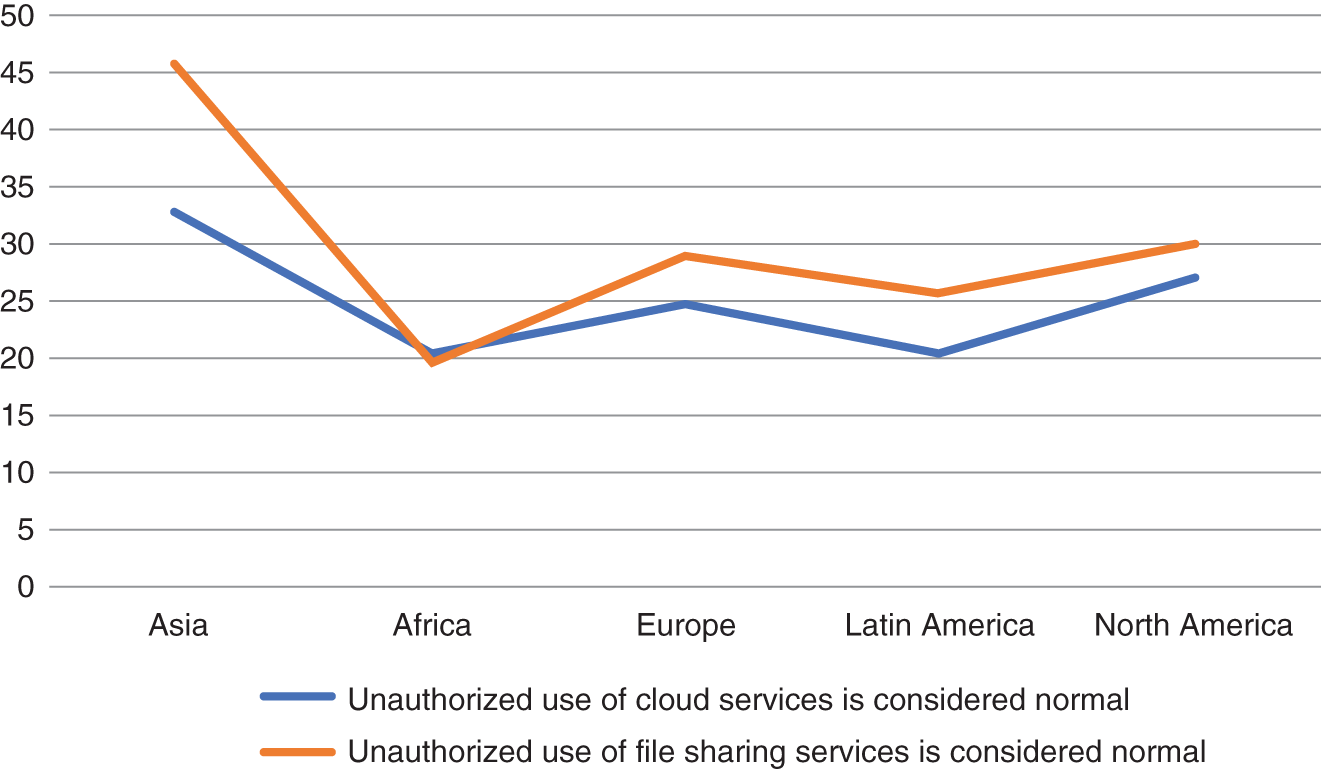

As shown in Figure 6.2, employees report that unauthorized use of cloud services and file sharing services is considered normal by a minimum of 20 percent of employees, all the way up to 54 percent of employees in Asia. Depending on where your organization operates, between one in two and one in five employees consider it normal, and thus okay, to circumvent organizational security policies to get their job done. What security norms exist in your organization? How are those norms impacting your risk?

Figure 6.2 Use of shadow IT across regions

Confidentiality and Insider Threats

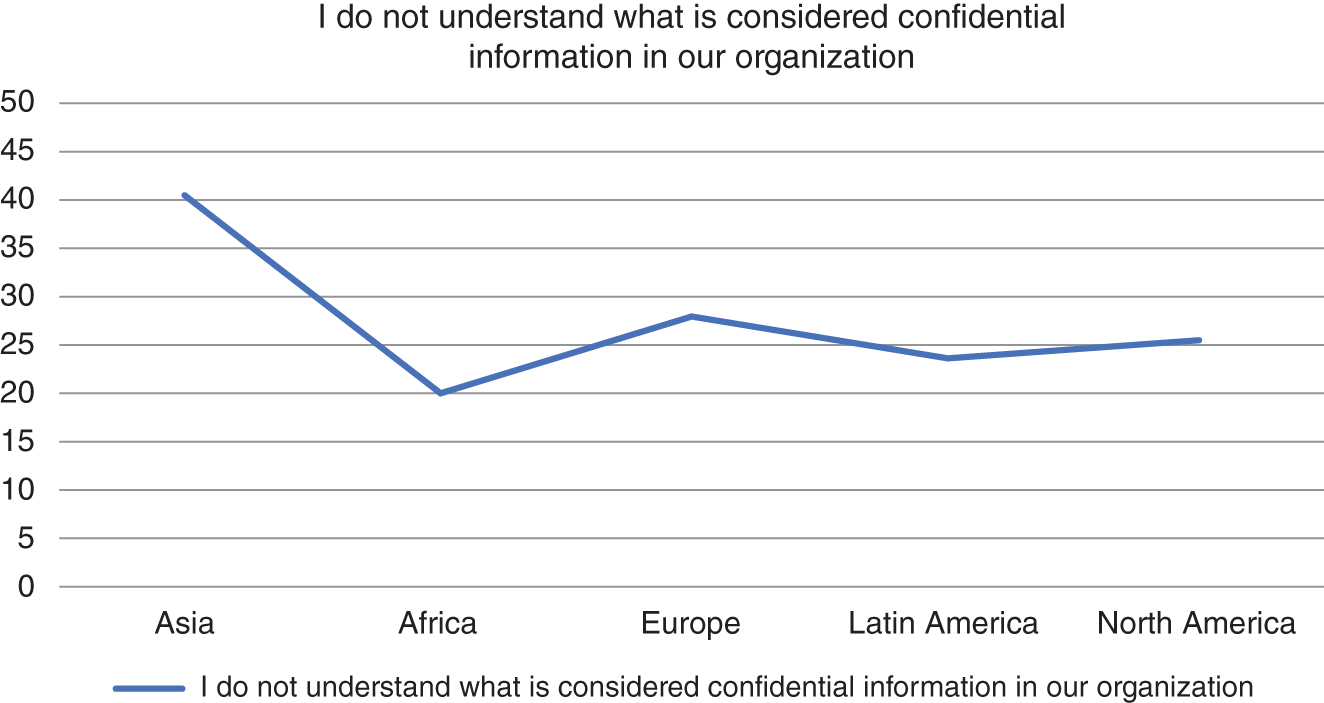

Here's another example. We wanted to study how well employees are able to determine what confidential information is in the context of their workplace. Our research shows that many employees do not know what is considered confidential information. As shown in Figure 6.3, this lack of understanding represents a serious insider threat, as between 20 percent and 40 percent of employees globally struggle to know what company confidential information is and what it is not.

Figure 6.3 Employees struggle to properly classify information.

Understanding what is considered as confidential within an organization represents an issue within the cognition dimension of your security culture. You can address this via the dimension of communication. This can also be addressed by social modeling via norms and responsibilities.

Last Thought

By now, you can see that culture is something that can be demystified. It can be defined and measured. There's power in being able to do so. Understanding these dimensions of culture empowers us to uncover insights and useful facts about our organizations.

Takeaways

- Our working definition of culture is: Security culture is the ideas, customs, and social behaviors of a group that influence its security.

- A scientific understanding of security culture requires us to break culture down into measurable components. We call these the seven dimensions of security culture.

- The seven dimensions of security culture are: attitudes, behaviors, cognition, communication, compliance, norms, and responsibilities.

- Each dimension influences and is influenced by the other dimensions.

- Influencing culture is about understanding the interplay between the dimensions.

Note

- 1 Back when Kai and team first began their formal study of security culture, very little evidence-based research of relevance existed. As of this writing, in 2022, KnowBe4 Research is cooperating with research units around the world to analyze data on millions of employees to refine our theoretical model to match the real world.