CHAPTER 4

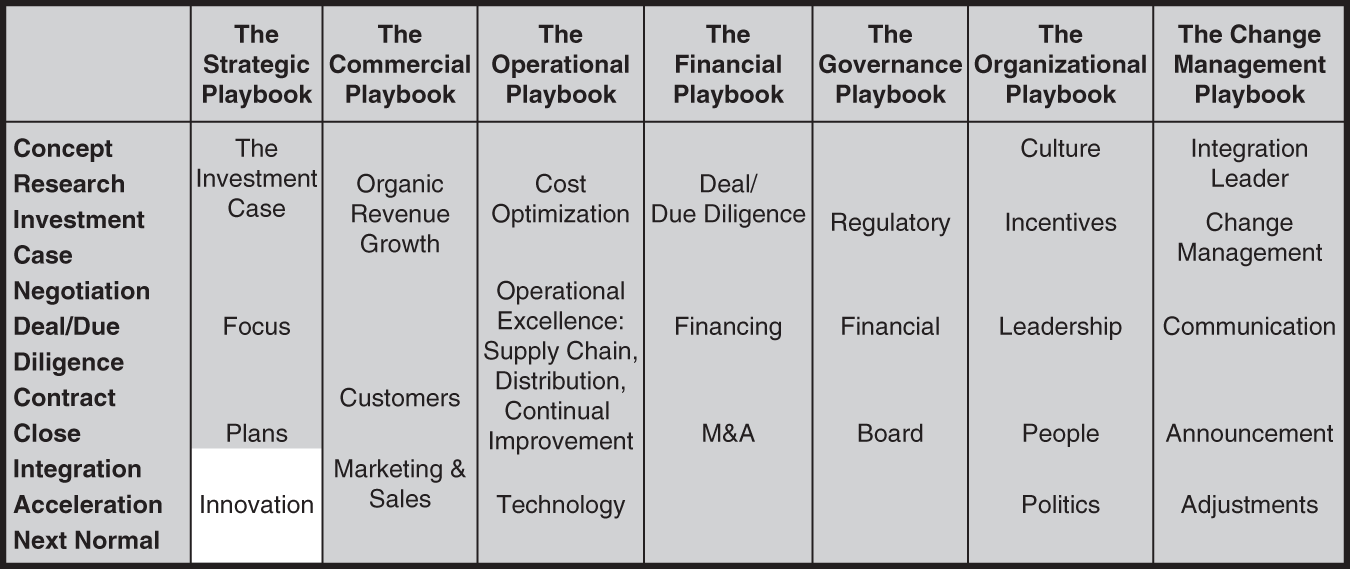

Innovation: A Fundamental Strategic Choice

The fourth component of the strategic playbook is innovation. The choice to innovate and how you innovate are strategic choices.

Choose whether your innovation will drive new products, next version of existing products, or higher prices—most likely in design- or service-focused organizations or drive down your production or delivery costs.

Full disclosure: This chapter is not like the others. Neither it nor innovation travels in a straight line. It's a curation of several of George's articles on innovation and creativity. Some will love this. Some will hate it. If you find yourself hating it, feel free to move on to the next chapter.

With that said, the flow of this chapter moves from overall tips to innovation strategies to creativity to systems. Take these innovation tips and strategies into consideration as you build out your strategic, commercial, operational, and financial plans and drive success with your mergers and acquisitions (M&A) or private equity (PE) deal.

Innovation Tips

The holy grail of innovation is the moment of sudden breakthrough. But those moments don't happen in vacuums. As suggested by some of the top names in business at the 2013 C2-MTL conference in Montreal, you must (1) prepare in advance, (2) focus on solving problems, and (3) follow through to turn ideas into reality and stay ahead of your competition.1

At the conference, George had the chance to interview Neri Oxman, John Mackey, Bobbi Brown, Diane Von Furstenberg, and Richard Branson after their presentations. Here are some tips from what they told George that can help spark your next flash of innovation.

Look at the World with a Child-Like Innocence.

Oxman and her MIT Mediated Matter group have moved beyond “bio-mimicry” to actually designing with nature: bio-inspired fabrication. Their new silk pavilion was actually created by 6,500 silk worms. She told George that she envisions scaling this idea with a swarm of 3-D printers to expand beyond any one printer's gantry as part of her search for “variations in kind” moving well beyond “better, faster, cheaper, bigger.”

In George's interview with Oxman at the C2 Conference in Montreal, Oxman told George about her “fork in the road.” She's a trained architect and designer. The choice she faced was whether to focus on design or go into research. She chose research because it gave her the opportunity to design her own technology. It allowed her to influence both products and processes—both influenced by nature.

She's a big proponent of variations in kind—true innovations. She's convinced these come from “being vulnerable,” not so much from solving a problem as from innocence and different worldview. It's that different worldview that allows the innovator to come up with solutions new to the world when problems do come.

Invite Others in on the Innovation Process.

Mackey is certain that Whole Foods must continue to innovate to stay ahead of its competition and that its conscious culture is its only competitive advantage. As Whole Foods adds stores, he insists on “No me-too new stores.” He told George he holds his division presidents accountable for innovation. “We value it and encourage it.”

One of Mackey's tenets is to “decentralize as much as possible.” This goes well beyond region, well beyond store level, to the teams within the stores. He pushes experimentation, knowing full well that “most fail.” He's fine with that because the “successful ones spread.”

He uses loose innovation guidelines, if any at all. Suggesting instead that if people go too far his leadership can always “tug” them back in. He's convinced it's easier to do this than to get people to innovate in the first place.

He told the story of walking a new store in San Antonio 22 years before. His wife pointed out that the few people in the store were not likely to buy Whole Foods' value proposition over the long-term. She was right. The store closed. But then 22 years later, Whole Foods opened a new store in almost the identical spot. When Mackey and his wife walked this new, booming store, he told her, “You know all those people that were never going to shop here. They're all dead. These are their children.” Some ideas are right, just not at the time.

Focus on Unsolved Problems.

Brown told George how she was on a TV shoot and had forgotten her eyeliner. To make do, she grabbed a Q-Tip and used it to brush some mascara on her eyelids, solving her immediate problem. The next morning, she was surprised to see the mascara still in place. The gel in the mascara had made it last. She called her design team and had them mock up the first gel liner, which is now her most copied product.

Many of Brown's innovations have come from thinking, “It would make so much sense if…” She describes these as “random ideas mixed with common sense.”

This was just one of the examples Brown shared with George. She also related how using a clean baby wipe to remove her makeup prompted her to create a baby wipe–like makeup remover. And she told George about wanting to wear cowboy boots with jeans she had. When they wouldn't fit, she cut them off—the boots, not the jeans. These stories all go to her philosophy of having a clear vision but then being open to change direction as needed. She's good at this because she seems to be able to understand what's needed next. Definitely a big idea to change direction before anyone else knows you need to.

George admits this was a difficult interview for him. He's still not sure he understands what the difference is between mascara and eyeliner. But Brown made it easy for him. She seemed to genuinely enjoy teaching a complete ignoramus (George) about what she did. George thinks that's part of what enables her to innovate and connect.

After Initial Success, Follow Through.

Von Furstenberg told George her wrap dress happened “by accident.” Her original T-shirts morphed into wrap tops and then into wrap dresses, catching on because they were “easy, proper, decent, flattering, and sexy.” They may have happened by accident originally, but their ongoing (then 40-year) success is directly related to Von Furstenberg's follow through.

It's often difficult to separate the brand from the personality. On one hand, while a major attribute of the Virgin brand is Richard Branson, and a major attribute of Apple was Steve Jobs, and a major attribute of Walmart was Sam Walton, in each of these cases the brand name and the personality were different. Those brands survive their founders. It's harder when the founder's name and brand name match as they do with von Furstenberg.

Of course, there are examples of success. The Disney brand is thriving—perhaps because its sub-brands are anything but Mickey Mouse. McDonald's is a golden arch, and maybe a clown. Very, very few people think of Richard and Maurice.

Von Furstenberg has spent time thinking about the difference between the brand and herself. A big part of her follow through is setting up the brand as her legacy: celebrating freedom, empowering women, color, print, bold, effortless, sexy, on the go. Of course, she's a living example of the brand now. Over time, others need to step up as that example.

Aim Higher Than Your Competitors.

Branson has achieved remarkable success taking the Virgin brand into industries “out of frustration” with existing record, airline, and telecommunication companies and the like. He looks for “obvious gaps in the market” and launches products or services that are “heads above everyone else.” He told George that keeping them above everyone else is the key to ongoing success.

When pushed, Branson described the Virgin Cola example:

Virgin Cola was our greatest success in that we were so successful in the UK that we absolutely terrified Coke. They sent a 747 with bag loads of money and 20 SWAT teams to the UK and we suddenly found it disappearing from all the shelves. They decided just to stop the company completely before we could get going out around the world. Because you've got two cans of soft drink, although people at the time preferred the Virgin brand of cola—we were outselling them and Pepsi at 3:1—we didn't have a fundamentally better product. When British Airways tried to do that to us in the aviation business, we were able to beat them. We were not in soft drinks.

It's one of Branson's main themes. As he said in a 2013 graduation speech:

We always enter markets where the leaders are not doing a great job, so we can go in and disrupt them by offering better quality services.

He grew so tired of waiting for NASA that he launched his own space travel program. This is definitely a man who reaches for the stars over and over again, as he did when he traveled into space himself in 2021.

At the same time, anyone in the main conference room when Branson spoke at C2-MTL had to have been struck by how he and the audience engaged. His Q&A time with the audience turned into a series of extraordinarily inspiring conversations as he wanted to understand the questioners' context, hopes, and ideas. He was genuinely curious and offered genuinely helpful advice to each individual. We all walked out thinking he deserved all the success he has had and looking forward to the contributions we know he's going to continue to make to the world through “The Elders” and all the other great programs he's enabling.

Race to the Top.

The fundamental choice is whether to compete on price or on differentiation. Competing on price is a race to the bottom with no winners. Competing on differentiation requires engagement with each of three phases of innovation.

Unfortunately, more and more are racing to the bottom in the face of a long-term decline in creative skills. Conference attendee Kraner told George how he had founded the Hatch Experience a decade ago to combat this, gathering diverse groups of next generation influencers, global thought leaders, and community builders annually to mentor each other in a veritable petri dish of creativity and inter-disciplinary idea generation.

Make the right choice. Race to the top. And help others race to the top. Then we'll all win.

Innovation Strategies

Evolutionary Versus Revolutionary Innovation

A Procter & Gamble (P&G) alumni reunion years ago included a chief executive officer (CEO) panel on innovation facilitated by Tim Brown, president and CEO of the innovation consultancy IDEO. Panelists included P&G's then chair and CEO A. G. Lafley, Steelcase's then CEO Jim Hackett, and Meg Whitman, who at that time was heading up eBay. At the heart of this panel was a discussion of the difference between evolutionary innovation and revolutionary innovation.2

The panelists generally agreed that large organizations like P&G, Steelcase, and eBay could be very good at evolutionary innovation. Their scientists, researchers, and developers were more than capable of building on their organizations' existing strengths and making step-by-step incremental improvements. This is a valuable capability that helps these organizations continue to evolve.

However, larger organizations often struggle with revolutionary innovations because they require different capabilities, mindsets, and cultures than the ones that made them successful. Unlike smaller companies, large, successful corporations have much more to lose. New and different projects that don't serve current customers and are not in line with current product or service offerings are often viewed as distractions and thus downplayed. It's less tempting to bet the ranch on a new idea when the ranch is big.

eBay and PayPal

During the panel discussion, Whitman discussed how eBay had looked at buying PayPal early on in its existence. She told the group that she had decided not to buy it because she didn't think it could have survived inside of eBay. Instead, Whitman waited until it was a big enough company to make a meaningful impact. It was better for eBay to pay more for a stronger PayPal later, than to pay less for a weaker, unsustainable PayPal earlier.

What goes around comes around. As part of its explanation for why eBay's then CEO John Donahue was putting 38-year-old Zong founder David Marcus in charge of PayPal, the Wall Street Journal noted it was so that Marcus could “use his entrepreneurial background to operate PayPal ‘like a smaller company.'”

Procter & Gamble

P&G faced the same issues. At that time, only about 15 percent of its innovations were meeting revenue and profit targets. Lafley decided it could do better by looking for a blend of evolutionary and revolutionary innovations. He tasked Bob McDonald, then chief operating officer (COO) and later CEO, and chief technology officer (CTO) Bruce Brown with the task.

Brown described their progress, discussed why P&G has been able to triple its innovation success rate, and offered some thoughts for others thinking about innovation. Looking at P&G's strategy through the lens of its behaviors, relationships, attitudes, values, and environment (BRAVE), we can get a sense of why they have been so successful. Let's look at these components in reverse.

Environment P&G remains committed to innovation. As Brown told George, “Innovation is the primary driver of our organic growth.” When he took over as CTO in 2008, one of the first calls he got was from former CEO Smale, who reinforced the importance of innovation and went through each of P&G's $1B brands, laying out the technological innovation that had produced a point of inflection in its growth.

Values P&G is all about “touching and improving lives.” You can't improve peoples' lives with the same solutions to the same problems. Thus, innovation matters a lot to P&G's ability to fulfill its purpose.

Attitude Brown knew that P&G's “culture would default to evolutionary” innovation if left on its own. Indeed, between 2003 and 2008 the size of P&G's initiatives declined by 50 percent. To counteract this trend, P&G's senior leadership adopted a more assertive attitude and pushed each category toward blended innovation, which layered revolutionary innovations on top of its commercial and sustaining innovations, looking for ways to innovate within its categories (like new detergent delivery systems) and beyond its categories (like dry cleaners).

Relationships P&G innovates to improve lives through its business groups. While it invests in breakthrough technologies that can work across categories, the rubber meets the road at each category's annual innovation review where they determine which category needs to grow. That focus serves to strengthen the relationships between the 8,000 scientists and researchers (1,000+ PhDs), in 26 innovation centers on five continents, and the business units.

Behaviors This organization's innovation program is inspired by its consumers. All behaviors around strategic thinking and implementation drive to the consumer whether it's a new-to-the-world technology, a new application of a technology, or an evolution of a technology.

Which Innovation Approach Is Right?

They all work. Each is right—for different organizations and different contexts.

- If you are a startup on the cutting edge with not much ranch to bet, go for it. Revolutionize the world. If you don't, you won't get noticed.

- If you are Apple and your ranch is built on revolutionary innovations, keep going. Stick with the attitude that made you successful in the first place.

- If you are a large, successful company with a big ranch and a culture not prone to revolutionary innovation, stick with evolutionary innovation—especially if you're in commodity category where you have to manage costs.

- If you can blend evolution and revolution and are prepared to invest to do so at a level comparable to P&G, the blended approach may work for you.

They all work, but not at the same time. Pick the one that's right for your situation, business model, and organization.

The Innovation Versus Scale Trade-Off

The most effective senior leaders are master delegators. Before doing anything themselves, they ask “Who can do this task instead of me?” Then Minority Business Development Agency head Henry Childs said that was now the wrong question. Instead, they should ask, “What can do this task instead of any of us?” They should do this in areas they can scale while investing in their areas of competitive advantage.3

Childs said this as part of the interactive state of the market conversation at a CEO Connection Mid-Market Convention. One of the recurring themes there was how artificial intelligence is fueling the new industrial revolution. It's all about leveraging technology to scale through points of inflection.

In a different session, Wharton Professor Gad Allon explained the difference between growth and scale. He suggested growth generally involves increasing revenues and costs together. Scaling involves growing revenues faster than costs.

Assume you're in the business of carrying boxes down a flight of stairs. You can grow your business by hiring another person to help you. Your revenues and costs increase. Or you can leverage a ramp and move more boxes yourself. Your revenues increase, but your operating costs do not. That's leverage.

There's an obvious trade-off between efficiency and differentiation. If you're leveraging a tool or technology to scale up, your competitors can do the same. Since the price of everything tends to get competed down to its marginal cost over time, you could end up in a race to the bottom before you blink.

Professor Allon suggested leaders should ask four questions: “Are we propelled to scale? Are we willing? Are we able? And are we ready?” He suggests not everyone needs, wants, and can scale. “Scaling up often means giving something up.” If that “something” is the competitive advantage that justifies your superior margins, scaling up may be exactly the wrong thing to do.

Another speaker suggested a middle way. Instead of making a people versus technology trade-off, that speaker proposed thinking in terms of both and “using technology, outsourcing or managed services to complement or augment” your people.

Implications for You

Thinking this way adds an important dimension to your strategic resource choices. As discussed, all companies design, produce, sell, deliver, and service. A fundamental premise is that you're better off picking one primary area of focus, investing to be best in class in that and efficiently managing everything else to fuel investment in that area.

Asking what instead of who changes your approach to this. More efficient design, production, delivery, or service could come from outsourcing part or all of those functions, employing lower-paid people, or leveraging technology to make fewer high-caliber and highly paid people more efficient. Of course, this applies to your primary area of focus as well. There's no reason not to leverage technology to make things easier for all your high-caliber and highly paid people.

The moment you outsource something core to your competitive advantage, you give up your competitive advantage. But there should be no downside to leveraging technology to complement or augment the efforts of the people giving you a competitive advantage.

Where Innovation Meets Scale

The mid-market is where innovation meets scale. Mid-market companies are generally too big to be as nimble as startups and too small to have the scale of huge corporations. This is why the speaker's thinking about using technology, outsourcing, or managed services to complement or augment people should be generally appealing to the mid-market.

While it's generally appealing, it's specifically wrong in some circumstances. Where you have a competitive advantage, you have to invest in talent and knowledge to fuel predominant or superior innovation. Ask who, and leverage technology here carefully. On the other hand, in areas where it's good enough for you to be strong or merely acceptable, ask what and outsource, deploy managed services, or leverage technology liberally to free up funds to invest in your areas of competitive advantage.

Creativity

The Three Keys to Bringing Out the Best in Extraordinarily Creative People

Managing extraordinarily creative people is challenging if not impossible. But you can bring out their best if you give them leverage, inspire, enable, and empower them. Their leverage comes from understanding and taking full advantage of their own natural talent, temperament, and inclinations. Inspiring them is about protecting them, pointing the way forward and encouraging them. Enabling and empowering them is about giving them the resources, time, and space they need to imagine, play, practice, and create.4

By anyone's definition, Salient Technologies' David Yakos is extraordinarily creative. Origins magazine describes him as one of its 45 top creatives and an “inventor, maker, designer, painter, adventurer, and engineer. From aerospace to toys, he blurs the lines between art and engineering.”5 (This last piece sounds a lot like what sparked the magic at Disney's creative oasis—Imagineering.)

Leverage

The world needs three types of leaders: artistic, scientific, and interpersonal. They need to be creative themselves and bring out creativity in others. For example, Yakos likes to “confuse the world of art and engineering.” Just as he is part artist and part mechanical engineer, his product development process blends creativity and practicality “from ideation to production”:

- Conceptual design, where you explore the look and function of the concept

- The prototype process, where you physically and digitally test the feel and function

- The production design, where you communicate with the factory the design intent using manufacturing files and engineering drawings

Yakos's mother saw this innate talent and nurtured it. In an interview with Tanya Thompson, he described how

my mother cut down an empty drier box, filled it with supplies including empty shampoo bottles, egg cartons, string and everything else I would need to build my first spaceship, first homemade pair of paper shoes and a cardboard robot suit. It was David's Creative Corner. I could visit that world and come back with something new, an invention that was unique and never before seen.

Yakos has a natural curiosity, intellectual playfulness, and a keen sense of humor and is aware of his own impulses.

Inspire

Extraordinarily creative people need to be protected, directed, and encouraged. At the same time, Wilson suggests they need to be uninhibited and willing to take risks given their heightened emotional sensitivity and being perceived as nonconforming.

Yakos knows that “all great businesses begin with an idea, but it takes engineering and product development to turn an idea into a reality.” That's his focus and his firm's focus. And they've done well through the years, winning Popular Science's Best Prototype of 2013 and then the Chicago Toy & Game Group's Toy & Game Innovation (TAGIE) award for excellence in toy design for David's Mega Tracks for Lionel Trains.

Enable and Empower

Enabling and empowering extraordinarily creative people is about tools and time. They need resources, connections, and basic tools. And they need time to play and learn in line with Wilson's premise that the most creative go through a large number of ideas, often thriving in disorder and chaos.

Yakos told George that

people are almost embarrassed with their own creativity. We need to give people permission to stop being adults and engage in child-like imaginative play. It's not about learning how to be imaginative or creative. It's about never growing out of it…. I live in a safe place where it is okay to have silly ideas and safe to fail as part of taking “a broad sweep of ideas, (and) polishing the best ones.”

And they need people around them with complementary strengths that can sometimes serve as the adults in the room.

Implications

- Don't try to fix extraordinarily creative peoples' “opportunities for improvement.” Help them be even better at what they are already good at.

- Encourage them by protecting them, pointing the way forward and recognizing the cool things they come up with and do.

- Give them the time and space they need to imagine, play, practice, and—wait for it—create.

Inspiring, Enabling, and Empowering Evolutionary Innovation—from Middle Managers

Inspiring, enabling, and empowering evolutionary innovation is one of the fundamental jobs of leaders. This is because evolutionary innovation is essential to an organization's survival and won't happen on its own.6

Having figured out how to determine whether evolutionary or revolutionary innovation is right for your organization, the problem to be solved here is how leaders can inspire, enable, and empower that evolutionary innovation. Fortunately, Tim Ogilvie, CEO of Peer Insight and coauthor of the book Designing for Growth, has a point of view on how to do this, which he recently shared in Time:

Innovation depends on the three P's: Passion, Permission, and Protocols. (Natural innovators) run on Passion, get the little Permission they need from their VP, and…make their way without much in the way of formal innovation Protocols.7

Ogilvie went on to talk about the need to flip the formula with middle management, leading with permissions and protocols before adding passion. He then took George on a deeper journey through this approach.

Permission

Evolutionary innovation is generally prompted by solving a known problem where many creative solutions are possible. Permission involves asking people to solve that problem and giving them resources with which to do so. A lot of people in organizations who may be reluctant to step up as “innovators” are happy to help solve a problem when asked. So set the expectation by asking for help.

Then give them the physical and emotional space they need to innovate. 3M does this by explicitly calling on all its employees to spend 15 percent of their time working on something new. Google requires 20 percent. Problem solvers need relief from their day jobs to work on your problem. They also need a space in which to innovate. This could be a project room, their own web room, or an empty drier box, or tree house, but they need time and space that makes them feel safe and a deadline to produce their best answers.

Protocols

By definition, asking people to innovate is asking them to step out of their comfort zone. There will be a natural fear of failure. You need protocols to shift the frame away from success or failure and focus instead on learning. One of Ogilvie's main suggestions is to borrow from the scientific method: Ask people up to come up with hypotheses and design experiments to test them. A good experiment succeeds when it either proves or disproves the hypotheses. Teams treat experiments differently from tests. Conducting experiments taps into our natural curiosity, whereas performing tests can trigger a fear of failure.

Passion

Once they have been given permission and are supported by the right Protocols, these evolutionary innovators will naturally discover their Passion for creative problem-solving. Encourage these people. Give them permission to play and their enthusiasm will often infect others.

Some team members may not be at all excited about innovation. That's OK. Don't push them to innovate. Instead, invite them to contribute in some small way. Everyone likes to be thought of as a contributor.

The bottom line is that innovation is not an optional exercise. Darwin's lesson is that survival of the fittest is about those best able to adapt. Adapting requires innovation. You can't stand still. If you're not adapting and innovating, you are falling behind your innovating competitors. If you fall too far behind, your very survival comes into question.

So give your people permission to innovate by asking them to solve known problems. Put in place protocols that make it as easy as possible for people to innovate, and inspire a passion for innovation, problem-solving, or at least contributing.

Why Adding Constraints Increases Innovation

It is counterintuitive. You would think the more scope, time, and resources you have, the easier it would be to innovate. Chris Denson, director of Ignition Factory at Omnicom Media Group, says you would be wrong. He suggests, “The more limited you are, the more creative you have to be. Time constraints eliminate second guesses. Constraint is a unifier.” This may explain why larger, resource-rich organizations struggle with revolutionary innovation.8

Let's look at Denson's points one by one.

Mission Constraint Is a Unifier.

HATCH's Yarrow Kraner described the constraints adventure hostel Selina's cofounder Rafi Museri has had to deal with

to reimagine a new vertical, catering to a quickly evolving digital nomad audience, this group needed to move quickly, efficiently, and responsibly to scale at a pace that would put them on the map quickly, without breaking the bank. All of the furniture and fixtures are hand-crafted by up-cycling found trash, rubble, and debris and giving second life to previously consumed resources.

To accomplish scaling at this rate with such artisan craftsmanship, Selina's creative director Oz Zechovoy had been training ex-gang members to be carpenters, builders, and welders. They were quickly growing from 3 locations and then to 10 by the end of 2016 and to over 90 locations within the next 4 years, creating hundreds of new jobs and positively impacting Panama's economy.

In this case, the constraint forcing innovation was the overlapping missions: to build adventure hostels catering to the evolving digital nomad audience and, at the same time, to give products and people in Panama a second chance.

Time Constraints Eliminate Second Guesses.

An example of time constraints forcing innovation is found in the way NASA team members came together during the Apollo 13 crisis. Right from “Houston, we've had a problem,” the team reacted flexibly and fluidly to a dramatic and unwelcome new reality—a crippling explosion en route, in space.

The team went beyond its standard operating procedures and what its equipment was “designed to do” to exploring what it “could do.” Through tight, on-the-fly collaboration, the team did in minutes what normally took hours, in hours what normally took days, and in days what normally took months. This innovation was critical to getting the crew home safely.

The constraint here was all about time. Not only was failure not an option, but success also had to come fast. Very fast. This imperative broke down all sorts of petty barriers, and got everyone rallied around what really mattered, leading to innovation out of necessity.

The More Resource Limited You Are, the More Creative You Have to Be.

Kraner described Kalu Yala as an example of just this:

The world's most sustainable community—that started as a conscious real estate play, but the founder realized that it would take millions of dollars to build out a destination before attracting buyers, and flipped into an institution as its first priority, teaching while learning about sustainable best practices.

Can civilization and nature coexist? Can our diverse cultures coexist with each other?

The first phase and the foundation of the plan was the institute: an educational platform for students from around the world who are collecting, implementing, and documenting best practices in sustainable living. The work-study program had hosted students from all over the world from 25 countries and 150 colleges.

Kalu Yala's Jimmy Stice didn't set out to build an institute. But as he put it, “Constraints are what give a design its focus and ultimately, its true shape.”

Implications

Innovation requires one of the only three types of creativity: connective, component, or blank page. The surprise is that these thrive on less resources rather than more. Don't overwater your plants, and don't over-resource your innovation:

- Narrow and focus the mission.

- Give tight deadlines.

- Limit resources.

If you need innovation, put people in a box with limited resources and a tight deadline. The real innovators will thrive on the challenge and find surprising, new, and perhaps revolutionary ways out of the box.

Why the Route to Creativity Runs Through Distress

Want to prompt creativity? Make someone unhappy. If people are happy, there's no need to change. But if people are faced with others or their own distress, they will work to find creative ways to bridge the gap from bad to good and unhappiness to happiness.9

Happiness is good—three goods: good for others, good at it, good for me. This means there are three opportunities to create distress: others' distress, distress from strengths mismatch, or personal distress.

Others' Distress

Many of society's advances were born out of someone's finding new, creative ways to solve others' problems. Fire was born out of the need for a better way to keep warm. Vaccinations were born out of the need to protect people from diseases. Pet rocks were born out of the existential need for more meaningful holiday gifts. The list goes on and on.

Albert Einstein told us that we couldn't solve problems with the same level of thinking that created them. When some people's level of distress with others' unhappiness reaches a breaking point, they move to new levels of thinking and create new ways to solve the underlying problems.

Prompt creativity by helping people see others' needs.

Distress from Strengths Mismatch

The world needs different types of leaders: artistic, scientific, and interpersonal. Those leaders have different strengths and different ways of thinking. Some of the most creative ideas have come when those leaders are forced to think in different ways.

Doug Hall has been forcing people to do this for decades. Hall was trained as a chemical engineer and as a circus clown. He was a brand manager at Procter & Gamble, eventually becoming “master marketing inventor” there before starting his company Eureka Ranch. In its early days, Eureka Ranch drove creativity, stimulus, and fun and helped all sorts of business executives play outside of their comfort zone by deploying things like Nerf guns, water cannons, and whoopee cushions. (More on Hall later in this chapter.)

Howard Gardner suggests there are nine different types of intelligence:

- Naturalist intelligence (nature smart)

- Musical intelligence

- Logical-mathematical intelligence (number/reasoning smart)

- Existential intelligence (getting at the meaning of life)

- Interpersonal intelligence (people smart)

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence

- Linguistic intelligence (word smart)

- Intrapersonal intelligence (self smart)

- Spatial intelligence (visual/picture smart)

Thus, stimulate different leaders' creativity by getting them to access different types of intelligence than they normally do.

- Stimulate artistic leaders outside of their visual, kinesthetic, musical, linguistic comfort zones.

- Stimulate scientific leaders outside of their naturalistic, logical-mathematical, existential comfort zones (though I'm not sure anyone is ever really comfortable pondering the meaning of life).

- Stimulate interpersonal outside of their intrapersonal and interpersonal comfort zones, getting them to think like artistic or scientific leaders.

This all comes down to prompting creativity by making people think or act in new ways.

Personal Distress

Brand communication agency Sid Lee's Will Travis will tell you that if the road to creativity runs through distress, the road to extreme creativity runs through extreme distress. Travis has climbed several of the world's highest summits, including Vinson Massif in Antarctica in the most brutal –45 °C conditions imaginable, motorbiked with the Paris Dakar, and traversed the 18,000 Khardung La pass in the Himalayas and generally put himself in extremely stressful situations.

These experiences have helped Travis both see things in different ways and keep things in perspective. As he put it,

Facing situations of life and death implications elevates one's vision way above the severity of the business landscape, resulting in both centered and humanistic decision making, that business school nor mentors can never teach.

Travis uses this perspective to help the people he leads face and manage their own fears. It's painful when a client coldheartedly rejects a creative team's heart-invested work, but we have to keep it in perspective that it's not a life-threatening situation. Travis suggests, “You have to fail. Failure puts you in a friction zone, puts you in a zone where you have to make a decision, you have to change and do something different to survive and move on.”

Systems

How to Lead the Change from Haphazard to Systematic Innovation

Almost everyone accepts the importance of innovation. Why then do most organizations do it so poorly? That's because innovation is generally random, haphazard, one-off, and outside the norm. Instead, make it systematic and part of your everyday culture.10

Hall is a master innovator, always innovating himself and helping others innovate. His book Driving Eureka: Problem-Solving with Data-Driven Methods and the Innovation Engineering System has easy-to-understand frameworks, processes, and ideas. Additionally, it also contains valuable tools, along with some of Hall's best stories.

The book's fundamental framework deploys:

- Blue cards to focus your efforts

- Starting with the customer problem as what matters and why

- A meaningfully unique framework

- Diversity of ideas to multiply your impact

- A systemic process

Blue Cards

Hall suggests using one set of cards—blue cards—to charter teams. These lay out your purpose, what you see as the very important opportunity or system improvement, clarity on whether you're looking for “LEAP” or “core” innovation on a long-term strategic or project-specific basis, whether this applies to the entire organization or a specific division or department, your name for the effort, a narrative describing how you got here, the strategic mission, strategic exclusions (barriers), tactical constraints (e.g., design, time, resources, investment, regulation), and areas for project exploration or long-term innovation.

Customer Problem

Hall has taken a classic positioning statement and repurposed it to help frame innovation efforts. The elements include:

- Customer and problem (think target)

- Customer promise (think benefit)

- Product, service, system proof (think reason to believe)

- Meaningfully unique (dramatic difference)

Meaningfully Unique Framework

This is an evolution of the framework Hall has been using for literally decades.

Meaningfully Unique = [Stimulus mining / Drive out fear] raised by diversity of thinking

His definition of meaningfully unique is that people will pay more for something.

Hall has been against pure brainstorming forever. He sees it as just sucking the useless stuff out of tired people. Instead, he suggests providing people stimuli to prompt new thinking through exploring, experiencing, and experimenting, building off his early days of creativity, stimulus, and fun. None of this works unless you can give people permission to innovate and remove their fear of failure, embarrassment, and punishment.

And the value of diverse perspectives, people, and ideas multiplies the impact of everything.

Diversity

One of Hall's favorite quotes through the years has been “In God we trust. All others must bring data.” Data is an equalizer. Doing things like using Fermi estimating (breaking an estimate into discrete, bite-sized parts) help remove fear and make it easier for diverse people to participate. There's much more to be said about the value of diversity. Lack of diversity is one of the main reasons the highest-performing teams always fail over time.

Process

A core tenet of Hall's innovation engineering system is an easy-to-follow process: define, discover, develop, and deliver with plan–do–study–act cycles within it and a healthy dose of mind mapping to keep things moving. Blue cards charter groups that come up with ideas. Another set—yellow cards—helps groups track those ideas.

Yellow cards include idea headlines, customer–stakeholder, problem, promise, proof, price–cost, raw math, death threats (to the idea), and passion (why we care). They clarify whether the idea addresses a LEAP or core opportunity or system in line with the blue card used to charter the group.

In closing, Hall reminded George about the importance of

leadership's role in the process of enabling the system of development. Recall 50+ percent of value is lost during development. Simply telling people what to do is not enough. Leadership needs to embrace a new mindset where they take responsibility for the systems of development. Command and control and leadership by numbers needs to be replaced with “Commanders Intent” and systems that enable innovation by everyone. Only the leadership can do this, as only the leadership has the responsibility and authority for the whole.

How Directed Iteration Brings Order to Creative Idea Generation

On one hand, you want to inspire and enable people to come up with the most outlandish, wonderful new ideas. On the other hand, you need to move forward in a way that all can follow. Break the trade-off with directed iteration around a double l'enfant. Innovation requires the mind of l'enfant (child). A great model for orderly progress was Pierre L'Enfant's long-term vision for a new Federal City, now Washington, D.C., and how to get there in steps. Marry the two with directed iteration, continually building on your current best thinking on the way to your long-term vision.11

Neri Oxman and the Mind of L'Enfant

Oxman suggests the beginner's mind is filled with innocence. “As a child you think you are shrinking when you see an airplane take off.”

She's a big proponent of variations in kind—true innovations. She's convinced these come from “being vulnerable,” not so much from solving a problem as from innocence and different worldviews. It's those different worldviews that allow innovators to come up with new-to-the-world solutions when problems do come.

Preserving that innocence and wonder is essential in inspiring and enabling innovation. It's hard to do when constrained by the need to deliver reliable revenue and profit streams. This is why larger organizations tend to be better at evolutionary innovation and entrepreneurs tend to be better at revolutionary innovation.

Pierre L'Enfant

Washington, D.C., is relatively easy to navigate geographically. Planned in the late eighteenth century, lettered streets run east to west, and numbered streets run north to south. Avenues cut across in diagonals with large traffic circles, parks, malls, and public buildings placed appropriately. Contrast that to London, where taxi drivers have to study for 2 years to earn the knowledge to do their jobs, or Tokyo, where buildings in each 1 square mile zone are numbered in the order in which they were built and most streets do not have names. The difference is L'Enfant's long-term vision and plan.

After Thomas Jefferson agreed to support Alexander Hamilton's national finance plan in return for Hamilton's support for moving the capital to the banks of the Potomac River, Jefferson worked with L'Enfant on a plan for the city. Whereas Jefferson envisioned a relatively small grouping of government buildings, L'Enfant envisioned the people, organizations, and businesses that would inevitably be attracted to the new nation's capital. He began with a long-term vision for what the District of Columbia could be and then figured out how to get there in steps.

Directed Iteration

A critical step in the Battersea Arts Centre's (BAC's) scratch process is iteration. Their only objective is to come up with more interesting works of art. Given that, it doesn't really matter which road they take. (More on the scratch process in the next section.)

Alice asked the Cheshire Cat, who was sitting in a tree, “What road do I take?”

The cat asked, “Where do you want to go?”

“I don't know,” Alice answered.

“Then,” said the cat, “it really doesn't matter, does it?”

—Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

When it does matter, use your long-term vision to direct those innovative iterations, continually improving current best thinking as iterative steps along the way to that destination. This is as much an attitude as an approach. Creative ideas are fragile things. They don't survive criticism well.

- Start with long-term vision or the problem to be solved.

- Unleash your minds to create ideas.

- Take your current best thinking and ask, “What else would move us toward the long-term vision?”

- Create more ideas.

How to Create and Assess Ideas Better: Merge IDEO's Human-Centered Design and BAC's Scratch

Going into more depth on the BAC's scratch process, the path to better ideas runs through creating, assessing, pausing, and then doing it again as appropriate. This is based on a few premises:

- Beginnings are magic.

- None of us is smart enough to make it perfect the first time.

- All of us together are stronger than any one of us.

- Breaks are good.12

The steps combine IDEO's human-centered design and the Battersea Arts Center's (BAC) Scratch.

Create

- Prepare by learning, listening, and observing patterns of behavior and points of pain and inconvenience.

- Generate ideas—with champions to carry them through.

- Develop a minimum viable products and rapid prototypes.

Assess

- Get responses from different users, peers, others.

- Analyze, filter, and decipher those responses.

Pause

- Take a break to think about something else and refresh your perspective.

Again?

- Modify what you had to evolve your best current thinking.

- Iterate until you're ready to.

- Implement.

The steps of IDEO's human-centered design process include:

- Observation—patterns of behavior and points of pain and inconvenience

- Ideation

- Rapid prototyping (minimum viable product)

- User feedback

- Iteration

- Implementation

The BAC's artistic director David Jubb explains their scratch process as a “structured framework for artists developing work in partnership with audience.” Its steps include:

- Idea: Begin with a story, vision, challenge—with a champion to carry them through

- Planning: Develop an idea to a point where it can be tested.

- Test: Experiment, taking creative risks in public.

- Feedback: Listen and gather responses.

- Analysis: Filter and decipher feedback.

- Time: Take up space to think about something else.

Then, iterate back to a new improved idea.

In many ways, these are more detailed versions of the old total quality process of planning, doing, checking results, acting on the process, and returning to plan the next cycle.

Beginnings Are Magic.

Scratch and human-centered design both pivot off the idea. Whether you're an artistic leader trying to impact perceptions and feelings or a scientific leader who cares about solutions and knowledge, the spark is an idea, an inspiration, a testable hypothesis. These need to be championed, cared for, and nurtured throughout the process. They are the secret sauce, the magic.

Jubb agrees with that and goes on to say, “Part of Scratch is having the opportunity to feel like you're beginning, again and again, even when you've finished.”

None of Us Is Smart Enough to Make It Perfect the First Time.

Webster defines iteration as “a procedure in which repetition of a sequence of operations yields results successively closer to a desired result.” It defines rework as “to work again or anew.” Iteration is planned, progressive, and positive. Rework is unanticipated, wasteful, and demoralizing.

A new analyst joined the U.S. State Department when Henry Kissinger was secretary of state. He worked for weeks on a paper and gave it to his boss, who passed it on to Kissinger. It came back with one note on the cover: “Not nearly good enough. Do it again.”

The analyst worked all weekend and resubmitted. This time the note said, “Still not good enough. Do it again.” The analyst worked all night. When his boss arrived, he asked permission to give the report to Kissinger himself.

Kissinger said, “This is the third time you've submitted this report. Is it absolutely, positively the best you can do?”

“Yes sir.”

“In that case, I'll read it.”

That's rework. Had Kissinger set clear expectations and provided helpful, progressive comments along the way, the analyst would have been able to do better, faster.

All of Us Together Are Stronger Than Any One of Us.

This goes to the value of getting feedback along the way from people with diverse perspectives and ideas. This is about co-creating in mutually productive discussions as opposed to selling the single best way to do something

Breaks Are Good.

There's value in walking away from something for a period of time and then coming back to it. Thomas Jefferson made a habit of putting letters aside overnight and relooking at them in the light of day. Give yourself mental and physical breaks to create space and see things anew. Start by taking a break before you reread this particular section.

Why You Should Eliminate Your Chief Innovation Officer

The whole premise behind a chief innovation officer goes beyond useless to completely and utterly counterproductive. If one person is in charge of innovation, everyone else is not—and they must be. Anyone not innovating is falling behind those that are. Charles Darwin taught us that that is a bad thing. So: no chief innovative officers. No distinctions between scientific, artistic, and interpersonal leaders. Everyone is responsible for innovating, creating, and leading.13

From STEM to STEAM

At HATCH Latin America, Creative Coalition president actor Tim Daly explained to George why this is so important. He was one of the innovators and communicators at a session with President Barack Obama in early 2009. As they discussed the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education initiative to boost these subjects, Daly asked, “Where's the A? It's the arts that put engineering and technology in the human context. Arts are the emissaries and custodians of our culture.” Thus, STEM became STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics).

The argument for including arts in education is compelling. Daly shared some data:

- 70–80 percent of young people who get out of jail in Los Angeles go back. That drops to 6 percent for young people who take part in the Inside Out creative writing workshop.

- 30 percent of U.S. high school students drop out, but students who have taken arts programs through middle school are three times more likely to graduate than the norm.

- When you factor in the costs of recidivism and failure, an investment in youth arts programs returns $7 for every $1 spent.

This is why Daly “became radicalized about the importance of arts and art education.” As he puts it, science is “meaningless” without arts. Artists make people feel.

Daly led a breakout group at HATCH on arts and education. One of its ideas was how to move people's view of art from dangerous to irrelevant to being part of the answer. The idea was to involve all three of the different types of leaders the world needs: tapping the scientific leaders for the rational, data, value, and brain science arguments; the artistic leaders for the emotional connection and stories, and interpersonal leaders to deal with the politics and business of getting funding and support.

No False Trade-Offs

Innovation is too important to be left to the chief innovation officer. Everyone must innovate. Everyone must create whether they prefer connective, component, or blank page creativity. Science is too important to be left to the scientists. Everyone needs to understand science, technology, engineering, and math. And everyone needs to leverage their own artistic side to communicate facts in a way that taps into emotions and sparks value-creating behaviors.

However, as one chief innovation officer explained to George, when making a cultural shift (like following a merger or acquisition), a chief innovation officer “can be an effective catalyst for change, as long as that person's charter is to create the right conversations and underlying business processes that connect the appropriate functions in a powerful and integrated way.”

Break the trade-offs with some good old-fashioned gap bridging:

- Get everyone aligned around a shared purpose. Without a shared picture of your mission, vision, and values, nothing else is going to work. Determine where you are going to play and what matters and why.

- Build a common understanding of the current reality. Take a cold, hard, dispassionate view of the facts around where you stand with regard to your customers, collaborators, capabilities, competitors, and conditions in which you operate. Remember that adding constraints actually increases innovation.

- Bridge the gaps. Work through and implement choices around how you are going to win, how you're going to connect, and the impact you are going to have. This is where you mash up your scientific, artistic, and interpersonal leaders so they can leverage their individual strengths and preferences to innovate, create, and communicate together.

Words matter. So do eliminate chief innovation officer titles to help inspire and enable everyone to do their absolute best together to realize a meaningful and rewarding shared purpose.

Three Imperatives for Service Innovation

Innovating in a service-focused business works best if the innovations are (1) aligned with your core purpose, (2) meet a future consumer need, and (3) can be executed by your organization.14

Noodles CEO Kevin Reddy explained this model to George and how it works at his organization. Since dining out is a truly discretionary expense for every one of Noodles' customers, it must deliver a superior experience every time every customer comes through its doors. Ultimately, we're all in service businesses, so this applies to all of us.

Align Around a Shared Purpose

People in the organization must understand, believe, and act on its core purpose. Reddy knows that any innovation and change must flow from, and contribute to, that core purpose, connecting with both current and new guests.

In Noodles' case this is about how it defines the dining experience, which Reddy summarized as “really good food, served by genuinely nice people, in a friendly, welcoming place.”

Noodles differentiates itself by providing quicker service and a finer dining experience than other casual restaurants (though not as quick as quick serve or as fine as fine dining). It is about delivering a superior dining experience at a great value in terms of financial and time costs.

Understand Future Consumer Needs

Innovation is forward-looking. Solving yesterday's problems is important but not innovative. Copying what others do well is often a good approach, but it is not innovative. Reddy suggests that innovation starts with knowing and believing in where consumer needs are going, then creating a picture of what's important, followed by “inspiring and motivating people to embrace that vision.”

Thus, “true innovation is about taking risk.” Reddy's steps are:

- Choose the future consumer needs you are going to focus on.

- Create a picture of what success is.

- Get clear on the behaviors required to get there.

Do the Doable

Armed with possible ideas, Reddy suggests the next step is “really understanding what our system can execute.” It's a truism that a good idea poorly executed is not worth anything. Reddy and his team make sure the ideas build on their core purpose, move the organization toward where consumers are heading, and then make sure the whole organization:

- Believes in and is passionate about the innovation

- Is clear about how to bring the innovation to life

- Has the training and tools required to execute

Reddy gave George a good example of a Noodles' innovation. Surprise. Much of the “really good food” Noodles serves is noodle-based. (Who would have thunk?) Consumers are valuing more and more ethnic variety in their food options. So Noodles is serving an increasing array of global flavors.

One option is Japanese Pan Noodles. It's a consumer-driven idea in line with Noodles' core purpose. But execution is key as there's a “dramatic difference between getting it right and getting it almost right—with the consumer being really pleased and not happy.” Exactly 3 minutes is required to get the right caramelization; 15 seconds too little or too much doesn't work. Since Noodles is committed to going from order to delivery in 5 minutes, these 15 seconds count.

Japanese Pan Noodles work because they are in line with Noodles' purpose, meet an emerging consumer need, and can be delivered well—as must your innovations.

Take these innovation tips and strategies into consideration as you build out your strategic, commercial, operational, and financial plans and drive success with your M&A or PE deal.

The most up-to-date, full, editable versions of all tools are downloadable at primegenesis.com/tools.

Notes

- 1 Bradt, George, 2013, “Innovation Tips from Richard Branson, John Mackey, Bobbi Brown and Others,” Forbes (May 29).

- 2 Bradt, George, 2012, “Evolutionary, Revolutionary or Blended Innovation: Which Is Right for Your Organization?” Forbes (April 3).

- 3 Bradt, George, 2019, “The Innovation Versus Scale Tradeoff—Not Who, What,” Forbes (October 1).

- 4 “The Three Keys to Bringing Out the Best in Extraordinarily Creative People,” Forbes (November 2, 2016).

- 5 Per Chicago Toy Fair magazine September 26, 2016.

- 6 Bradt, George, 2013, “Inspiring, and Enabling Evolutionary Innovation—From Middle Managers,” Forbes (February 14).

- 7 Time online version: https://business.time.com/2012/08/17/how-to-get-innovation-from-the-big-middle/#ixzz2ALIo5qzx

- 8 Bradt, George, 2016, “Why Adding Constraints Increases Innovation,” Forbes (March 9).

- 9 Bradt, George, 2017, “Why the Route to Creativity Runs Through Distress,” Forbes (April 19).

- 10 Bradt, George, 2018, “How to Lead the Change from Haphazard to Systematic Innovation,” Forbes (November 13).

- 11 Bradt, George, 2018, “How Directed Iteration Brings Order to Creative Idea Generation,” Forbes (May 1).

- 12 Bradt, George, 2017, “How to Create and Assess Ideas Better: Merge IDEO's Human-Centered Design and BAC's Scratch,” Forbes (May 18).

- 13 Bradt, George, 2016, “Why You Should Eliminate Your Chief Innovation Officer,” Forbes (March 16).

- 14 Bradt, George, 2013, “Three Imperatives for Service Innovation,” Forbes (February 20).