CHAPTER 1

The Investment Case: The Heart of the Merger and Acquisition Leader's Playbook

The first component of the strategic playbook is the investment case. It guides every other part of the investment playbook and every other playbook. The first, fundamental questions go to what you want out of an acquisition or merger, how it would fit with what you've already got, and what you're willing to give up to get it.

What You Want

Synergy happens when two or more people or businesses work together to create new value, capture existing value, or prevent or slow the destruction of value. That leads to some of the different types of mergers and acquisitions and the different reasons to do them:

- Merging organizations with complementary capabilities and strengths to create something that no one else can do, like Stanley merging its hand tool and construction strengths with BLACK+DECKER's power tool strengths.

- Adding innovation or technology capabilities, like Disney buying Pixar to leverage its technology across all animation.

- Gaining access to a new market with a new business model or new Internet protocol, like Google buying Android to give it an operating system.

- Expanding product and service offerings, like executive search firm, Korn Ferry's string of acquisitions to add other human capital consulting offerings.

- Shoring up a weakness to stop destroying value, like Philip Morris buying Kraft foods and merging it with General Foods so the Kraft management team could provide needed leadership to General Foods or the second reason Disney bought Pixar, which was to acquire new leadership for Disney Animation.

- Repositioning a company in a new category (with higher multiples) like Delux's move from being a printing company focused on printing paper checks to merging into payment technology companies.

- Leveraging costs across the platform, like Coca-Cola's master bottlers swallowing up smaller bottlers to further increase their economies of scale.

- Creating critical mass for a platform company to enable future value creation, like regional companies merging to create a national or international footprint so they can expand geographically and serve national or international customers.

- Scaling the platform, where there are economies of scale, perhaps in an industry consolidation like Disney buying Marvel and then Lucas Films/Star Wars and then Fox after buying Pixar.

What You Are Willing to Give Up

You have to give up something to make any merger or acquisition work, whether it's cash or just a dilution of your control. You'd never do this if you didn't believe there would be a positive return on your investment (ROI) in an appropriate time frame.

If you're a public company, you'll need to manage that ROI in your quarterly and annual earnings announcements. Many public company investors will want to see accretion to earnings per share (EPS) every quarter. You will need to think about this aspect and ensure messaging and expectations are clear on when the merger will add to EPS. If you're a private equity firm, you'll need to manage that ROI within the time frame of the appropriate fund. If you're a family or family office, the ROI may be associated with generational wealth creation. Your ROI can be positive if you pay or contribute less or receive more for an asset than it's actually worth. In that case, there's a transfer of value between past and future owners with no need to chase synergies.

This book and this chapter focus on mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in which the combined parts are worth more together than they were separately—creating top-line and bottom-line growth through synergies.

Which Opportunities to Pursue

Knowing what you want and what you're willing to give up to get it points you in the right direction to consider all the alternatives, taking into account overall risks at a high level and how you might mitigate those risks.

British philosopher Carveth Read taught us “it is better to be vaguely right than precisely wrong.”1 Others encourage divergent thinking before converging on a solution. When it comes to looking at merger or acquisition targets, they are the same idea: Expand your thinking to look at vaguely right possibilities before narrowing in, getting more precise at each step.

In any case, make sure the opportunities tie directly into your strategic plan, building strategically important capabilities. Mergers and acquisitions are tactics, not strategies. Not thinking this way is one of the main reasons so many mergers fail.

There are four basic things private equity investors do to earn money:2

- Raise money from limited partners (LPs) like pension and retirement funds, endowments, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and wealthy individuals as well as the private equity (PE) firms and their partners' contributions to the deal(s)

- Source, due diligence, and close deals to acquire companies

- Improve commercial, innovation, and technology strengths and operations, cut costs, manage risks, and tighten management in their portfolio companies

- Sell or recapitalize portfolio companies (i.e., exit them) at a profit

When PE firms analyze companies for potential acquisition, they will consider things like what the company does (their product or service and their strategy for it), the senior management team of the company, the industry the company is in, the company's financial performance in recent years, emerging technologies, industry trends, risks, opportunities, the regulatory environment, reputation, potential competitive response, products and services, customers, and the valuation and likely exit scenarios of the company.

The main sources of value capture at exit include market share growth, growing revenue (and therefore earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization [EBITDA] and cash flow) substantially during the holding period, cutting costs and optimizing working capital (and therefore increasing EBITDA and cash flow), selling the company at a higher multiple than the original acquisition multiple, and paying down debt that was initially used to fund the transaction.

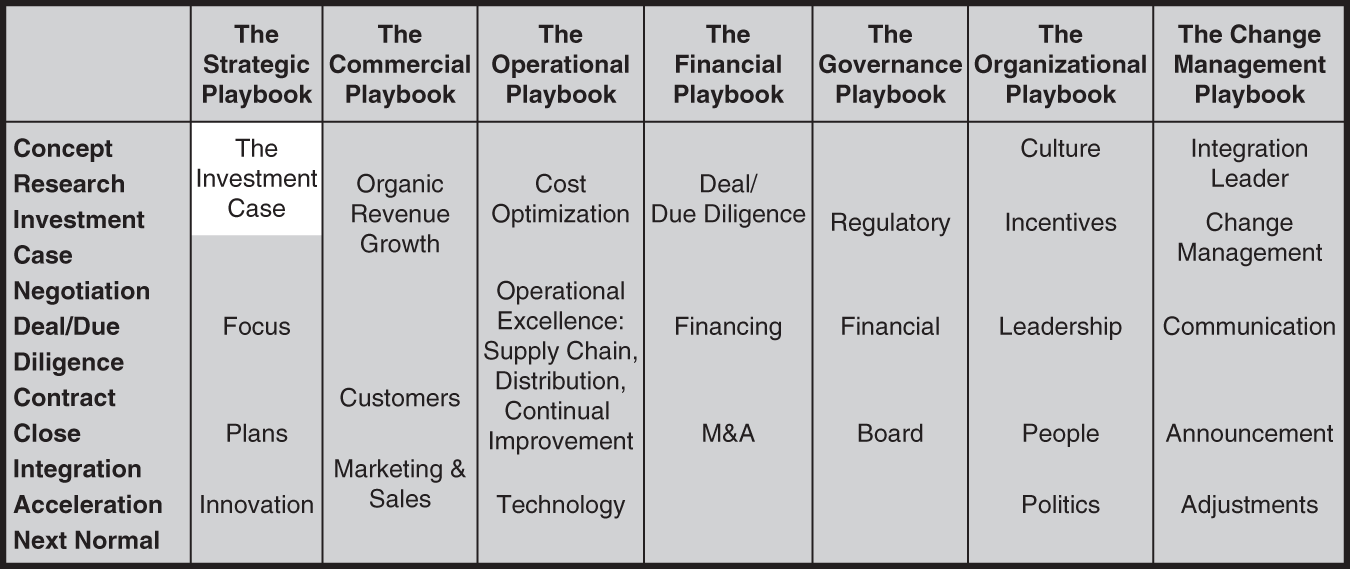

This leads to a framework for the investment case—simplified by design. Your actual investment case will include several layers of detail below this overarching framework.

The Path to Value Creation

As McKinsey's Andy West and Jeff Rudnicki laid out in their podcast on “A Winning Formula for Deal Synergies,”3 the highest synergy potential is found in industry consolidations, capability-led roll-ups, and geographic expansions. Small product tuck-ins, corporate transformations, corporate-led white-space acquisitions, new business models, and IP acquisitions may also be strategic fits.

Think through the core focus, overall strategy and posture, strategic priorities, enablers and capabilities, and organizational and operating priorities for the investment based on a fact-based assessment of the situation.

The 6Cs situation assessment is a framework for understanding the business environment by looking at:

- Customers: first line, customer chain, end users, influencers

- Collaborators: suppliers, allies, government and community leaders

- Culture: behaviors, relationships, attitudes, values, environment

- Capabilities: human, operational, financial, technical, key assets

- Competitors: direct, indirect, potential

- Conditions: social, demographic, and health; political, government, and regulatory; economic, technical, market, climate

Think:

- What: Objective, scientific truths—facts

- So what: Subjective, personal, cultural or political truths, opinions, assumptions, judgments, conclusions

- Now what: Indicated actions

Customers

Customers include the people your organization sells to or serves. These comprise direct customers who actually give you money, as well as their customers, their customers' customers, and so on down the line. Eventually, there are end users or consumers of whatever the output of that chain is. Additionally, there are the people who influence your various customers' purchase decisions. Take all of these into account.

FedEx sells overnight delivery services to corporate purchasing departments that contract those services on behalf of business managers. But the real decision-makers have historically been those managers' executive assistants and office mangers. So FedEx targeted its marketing efforts not at the people who write the checks, not at the managers, but at the core influencers. It aims advertising and media at those influencers and has their drivers pick the packages up from the executive assistants personally instead of going through an impersonal mailroom. FedEx trains its frontline employees on customer service and how to interact to retain business and grow share.

Collaborators

Collaborators include your suppliers, business allies, and people delivering complementary products and services across your ecosystem. What links all these groups together is that they do better when you do better. So it's in their best interest, whether they know it or not, to help you succeed. Think Microsoft and Intel, or mustard and hot dogs, or ketchup and hamburgers—though never mustard and hamburgers, of course.

Just as these relationships are two-way, so must be your analysis. You need to understand the interdependencies and reciprocal commitments. Whenever these dependencies and commitments are out of balance, the nature of the relationships will inevitably change. Think through your customer's purchasing cycle. Who comes before you? Who comes after you? If you're in corporate real estate, a relocation expert you can vouch for and trust is an obvious ally. In the M&A advisory business, attorneys, bankers, and other professional services firms pull in complementary firms to create the best outcome for their clients. However, a printing business could be your ally as your customer will need new letterhead and business cards to reflect their new location.

Collaborators are strategic partnerships whether that's intended or not. So, think strategically. The less resources you control in-house, the more important this is.

Culture

Some define culture simply as “the way we do things around here.” Others conduct complex analyses to define it more scientifically. Instead, blend both schools of thought into an implementable approach that defines culture as an organization's behaviors, relationships, attitudes, values, and the environment (BRAVE). The BRAVE framework is relatively easy to apply yet offers a relatively robust way to identify, engage, and change a culture. It makes culture real, tangible, identifiable, and easy to talk about.

Capabilities

Capabilities are those abilities that can help you deliver a differentiated, better product or service to your customers. These abilities include everything from access to materials and capital to plants and equipment to people to patents. Pay particular attention to people, plans, and practices.

Competitors

Competitors are those to whom your customers could give their money or attention instead of to you. It is important to take a wide view of potential competitors. Amtrak's real competitors are other forms of transportation like automobiles and airplanes. The competition for consumer dollars may be as varied as a child's college education versus a Walt Disney World vacation. In analyzing these competitors, it is important to think through their objectives, strategies, and situation as well as strengths and weaknesses to better understand and predict what they might do next and over time.

Conditions

Conditions are a catchall for everything going on in the environment in which you do business. At the least, look at sociodemographic, political, economic, technology, and climate trends and determine how they might impact the organization over the short, mid-, and long term:

- Social, demographic, health

- Political, government, regulatory

- Economic

- Technology—emerging innovation and trends

- Market—including consolidations and cross-vertical expansion

- Climate, weather

Pull these together into a Porter's Five Forces4 or a strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat (SWOT) analysis or the like and use that to inform your choices, starting with your core focus. Michael Porter's Five Forces are:

- Bargaining power of suppliers

- Bargaining power of buyers

- Threat of new entrants

- Threat of substitute products or services

- Rivalry among existing competitors

SWOT is a way of combining internal strengths and external opportunities into key leverage points and internal weaknesses and external threats into business issues. See Chapter 3 for more explanation and a SWOT tool.

For years, United Sporting Goods exploited its relatively strong bargaining power with suppliers and buyers to set market prices as the largest distributor of guns in the United States. It had no single supplier or buyer that accounted for more than 5 percent of their business. The threats of new entrants or substitutes was low, and its existing competitors were dramatically smaller than they were. Its Five Forces analysis was favorable. However, they completely missed the impact of Donald Trump's election on the gun market. United Sporting Goods expected Trump to relax constrictions on gun sales, leading to a market expansion, so it increased its inventory. Instead, it faced “slowing sales after Mr. Trump's election as worries about gun control ebbed among firearm enthusiasts.”5 This is why it needed to look at its SWOT.

FIGURE 1.1 Core Focus

Core Focus

The core focus of an enterprise depicted in Figure 1.1 informs its overarching strategy, culture, organization, and ways of working. Understand whether your new, combined organization's core focus is design, production, delivery, or serve. That choice dictates the nature of the culture, organization, and ways of working and flows into your overarching strategy and posture, strategic priorities, and enablers of those priorities, which then guide your organizational and operating priorities.

Overarching Strategy and Posture

Two things drive fundamental choices around the creation and allocation of resources to the right place in the right way at the right time over time in line with your strategic priorities:

- Drive customer impact and profitable commercial growth through product/service development, new offerings, innovation and technology, pricing, marketing, business development (markets, partners, etc.), increase sales to existing and new customers

- Enhance operational rigor and accountability through supply chain, production, distribution, service optimization

Strategic Enablers and Core Competency and Capabilities

These drive things directly increasing customer impact, revenue, and profitability (e.g., X-ray machines and radiologists to diagnose ankle surgical needs).

- Win by being: predominant/top 1 percent; superior/top 10 percent, strong/top 25 percent;

- Not lose by being: above average/competitive, good enough/scaled, or;

- Not do by: outsourcing or not doing at all.

Organizational and Operating Priorities

These help deliver the strategic enablers and competency and capabilities.

People

- The board

- Senior leadership (commercial, operations, tech and information technology, finance, human resources [HR], legal, research and development, M&A)

- Middle management

- Individual and team strengths including project management and transformation

- Incentives

Infrastructure

- Governance including board and systems

- Brand positioning and marketing materials, collateral, tools (e.g., websites)

- Financial reporting, tax, accounting, and compliance infrastructure

- Data, technology, IT, and security infrastructure

- Operational infrastructure including procurement and supply chain

- Organizational and HR infrastructure

- New product development infrastructure

Innovation and Technology

- Revolutionary invention

- Evolutionary steps

- Next version of product or service with what the customer wanted or did not even know was possible

Systems and Processes

- Enabling commercial growth and operational rigor

Balance Sheet and Cash Flows

- Deferred maintenance and modernization investments

- Growth-oriented capital spending

- Technology investments

- Back office: finance, tax, HR

Mergers and Acquisitions

- Bolting on to foundational platform for:

- Industry consolidation

- Capability-led roll-up

- Geographic expansion

- Product tuck-in

- Corporate transformation

- Corporate-led white-space acquisition

- New business model

- Intellectual property acquisition

- Taking into account competitive landscape and potential reactions

Fundamental Investment Case Model for a Merger or Acquisition

Step 1: Pay or Contribute Fair Value for What the Company Is Currently Worth.

Begin with the current value of the enterprise you're considering acquiring or merging with based on its current cash flows, when there is current cash flow. There are early-stage growth businesses and businesses in need or restructuring and transformation that are not producing cash flow today. In these cases, you need to think about the future value of the business, based on the current commercial success, once scale is obtained or the value the PE firm or acquirer can bring to these businesses and derive a fair value for these businesses. A couple of things that do not go directly into this calculation are:

- Their claimed EBITDA: Different organizations do different things with financing and interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Get to the current ground truth with cash flows.

- Their future projections—current, not future value

- Possible synergies—current, not future

- Improvements to the commercial or operations of the business

This is, of course, not what you're going to end up paying or contributing. But it's important input. The number you do care about is what you think you'll have to pay or contribute.

If you did pay or contribute fair value for what the company is currently worth based on current cash flows, you would reward the seller for what they've built and keep all future value creation. Of course, in the real world, others may be willing to give the seller a portion of the estimated future value. Couple that with some overestimation of future value creation and ego, and it's easy to see how people bid more than they should to “win” bidding contests.

You'll need an expected transaction price for your investment case. Pick a most likely number somewhere between “fair value” and “must have at any price.” Then bracket it with best-case and worst-case scenarios. Add in some financing assumptions for leverage and you're ready to go to the next step.

The next steps get at future state value creators: top-line growth, operational efficiencies, technology innovation, and the investments required to enable them.

Step 2: Grow Top-Line (Organically and Inorganically).

Project the organic growth that can come from synergies between the two enterprises. In general, these come from getting new customers or getting current customers to buy or pay more. But, for this exercise, take into account only increases that would not happen without the merger or acquisition.

Of course, you're going to consider opportunities and risks like general market growth or market consolidation and the competitive landscape that will impact everyone—including the value of your enterprise.

It is critical to think through what emerging technologies are possible during your expected hold period that could benefit or materially harm the future value of the firm. Amazon's growth has been a major benefit for a number of players in the value stream, including corrugate manufactures and shippers. On the other end of the spectrum, auto suppliers with key components tied to the combustion engines have seen valuations fall as electrification continues to grow, even a decade before the conversion happens. But they impact buyers and sellers whether or not they merge.

Classic synergistic revenue enhancers include:

- Cross-selling existing products or services to the formerly separate entities' customers either in the same or new markets.

- Getting existing customers to use current products or services in new ways—thereby purchasing more.

- Creating and then selling new products or services (that could not have been created without the merger or acquisition).

Then, separately, project the inorganic growth enabled by the merger or acquisition. These might include acquisitions, mergers, or joint ventures with other companies, brands, technologies, systems, and the like layered on to the new, combined platform—especially in a relatively fragmented market.

Step 3: Make Operational Improvements and Operational Engineering.

As we've said, this is what most people think of when they think “synergy.” While there is often the opportunity for some quick wins falling out of eliminating redundancies, the really valuable operational improvements don't “fall out” of anything. They require real work by people with real strengths.

Look at these in five buckets across the operating flow from procurement to intake to processing to inventory management to distribution:

- Operations strategy, which starts by asking where to play and then (1) doing the most important value-creating operations yourself and (2) outsourcing the less important and less efficient operations.

- Operational jump-shifts to improve quality and reduce waste and costs, perhaps fueled by new technologies, digitization, tools, systems, processes, footprint realignment, unlocking stranded capital, or scale. Scope is a function of resources (including levers) and time.

- Elimination of redundancies: They will be there. Take them.

- Cash and working capital management, especially the lag between money out (accounts payable) and money in (accounts receivables) and also opportunities to generate cash like contracting out unused production capacity.

- Lean, continuous, and incremental improvements, which may take longer to realize but create real value over time.

Step 4: Invest in Top-Line and Bottom-Line Enablers.

What you pay for an acquisition or merger is your first investment, but not your last. Step-changes in top-line growth and operating efficiencies won't happen without investing to realize them. Some of the enablers are more general, and some are more specific.

Think in terms of putting in place a full management team capable of managing another doubling of revenue for the next owner.

Governance engineering can also make a big difference. Think in terms of management equity, debt or leverage, board participation, all securing the license to operate legally, ethically, socially.

Strengthening brand differentiation with prospective and current employees, customers, suppliers, allies, influencers, and the communities in which you operate is always important.

Strengthening go-to-market capabilities through the sales pipeline: generating awareness, fueling interest, and then activating desire helps drive topline growth.

Financial engineering, arbitrage, or balance sheet and cash management including foreign exchange opportunities and risks all directly impact profitability and enable other growth drivers.

At the same time, make sure you're establishing the required infrastructure. For organizations focused on design, this might look like a new product development factory—like Michael Eisner and Frank Wells’s reboot of Disney's animation studio when they took over because they decided the core of the company was in animated film design; or efficient procurement and production machines—like Disney's development company because Eisner and Wells wanted to capture more of the share of wallets from theme park visitors; or a distribution network or ecosystem—like Disney stores to sell Disney character-driven merchandise; or service-delivery differentiators—like Disney hotels as part of capturing more of the guests' wallet share and better controlling their overall experience; all supported by:

- IT systems including enterprise management and business intelligence, customer relationship management

- Financial reporting systems

- HR management systems

Step 5: Improve Cash Flows and Pay Down Debt.

While this may fall out of successfully implementing steps 2-4, do calculate this and cash flow sensitivities into your investment case. Some deals will involve some creative financing approaches as well, generating their own synergies and value. And yes, you will need to do a bridge from current revenue, EBITDA, and cash flows to those in your future case, taking into account all the things that help and hurt.

Step 6: Realize Value in Increased Earnings or by Exiting or Recapitalizing When This Round of Value Creation Is Done.

You make investments to earn returns—the “R” in ROI. Sometimes the return is realized in increased earnings. Sometimes it's realized in an exit or recapitalization. Calculate that value one way or another. Bonus points for writing the investment case for the organization eventually buying your new, combined entity—whether or not you think you'd ever want to sell. Write their future investment case, and then make it happen.

Note the most up-to-date, full, editable versions of all tools are downloadable at primegenesis.com/tools.

Notes

- 1 Read, Carveth, 1989, “Logic: Deductive and Inductive,” Grant Richards, London, June.

- 2 Chen, Andrew, “What Do Private Equity Investors Actually Do?” InterviewPrivateEquity.com.

- 3 West, Andy, and Rudnicki, Jeff, 2020, “A Winning Formula for Deal Synergies,” Inside the Strategy Room Podcast (May 8).

- 4 Porter, Michael E., 1985, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: Simon and Schuster).

- 5 Gibson, Kate, 2019, “Gun Seller United Sporting Goes Bust, Partly Blaming Trump's Election,” CBS News MoneyWatch (June 11).