3.4

FINANCIAL OPTIONS

Option is a financial term that describes a common feature of many contracts. This feature gives one person in the contract the ability to make some kind of decision in the future, usually to buy or sell something at a fixed price. Being able to place a dollar value on the ability to make future decisions is a cornerstone of modern investing. Option contracts work by having one person pay another for the right to take some action in the future. The money paid by the buyer to the option writer when the contract is signed is called the premium. The decision to take action is an exercise. It is usually obvious when an option should be exercised. The difficult decision is determining how much to pay for the option in the first place. For example, if an option buyer purchased the right to buy gasoline in the future for $4.00/gallon, he would only exercise that right when prices were above $4.00. Otherwise, he would be wasting his money. The value of the option depends on the probability that prices will be above $4.00.

Options are important because it is possible to represent many types of investment decisions this way. For example, a combination oil well and refinery might be able to produce gasoline at $4.00/gallon. Owning this installation would give the owner the option to “buy” gasoline at $4.00/gallon for immediate resale. By comparing the cost of building and operating the installation to the economic value of the option, it is possible to determine whether this would be a good investment.

Financial option contracts, as opposed to approximations of physical investments, are an all-or-nothing investment. It is possible to buy a million dollars’ worth of options and lose everything. This is like buying insurance. Most often, the purchaser will pay a premium and have the contract expire worthless. Occasionally, the contract will pay off big when an unusual event occurs. Even though the size of the downside is small (losing the premium) compared to the potential upside (a huge profit), the odds of making a profit are stacked against the buyer. Similar to buying insurance, buying options is generally unprofitable. It only makes sense as part of a broader strategy. The option writer is taking on a risk from the buyer and needs to be compensated for taking that risk.

Two common applications for options are risk management and modeling energy investments. In the energy market, there are a lot of physical decisions that need to be made on a daily basis. Do I turn the power plant on and convert my fuel into electricity? Do I lock in a fuel supply for the winter now or should I wait a little longer? Should I invest in building a new power line between Oregon and Northern California? Option theory provides a way to quantify those decisions.

From a transaction standpoint, option trading requires both a buyer and a seller. The seller (the option writer) takes on the possibility of a big loss in exchange for money up front. The buyer pays a premium to the writer for that service. If the option pays off, the writer will need to find the cash to pay the buyer. With options, money is not magically created; it is simply transferred between the two parties. The option buyer is described as being long the option or being long volatility (since rare events will mean a big profit). The option writer is described as being short the option or being short volatility (since rare events will mean a big loss).

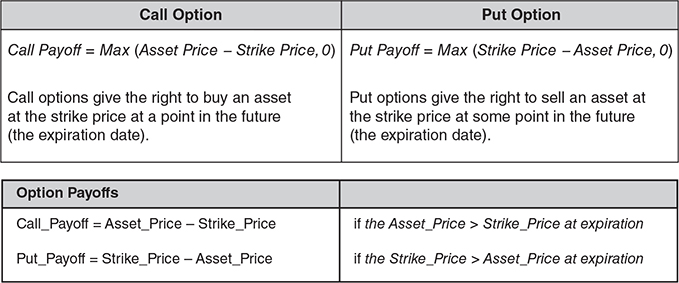

The amount of money that needs to be transferred between the buyer and seller is determined by the payoff of the option. Every option is assigned an exercise or strike price. This is the fixed price at which trading can occur in the future. For example, a call option involves the right to buy the underlying asset at a fixed price. The owner of a call option benefits when the price of the underlying asset rises above the strike price. This allows the owner to buy at a lower price than is otherwise available. The owner can also make an immediate profit by reselling the asset at the current price.

A put option works similarly. A put option gives the owner of the option the right to sell the underlying asset at a fixed price. If the market price of the underlying is greater than the fixed price, a put option is worthless. No one will willingly sell at a lower price than necessary. However, if the fixed price is higher than the market price, the put buyer makes a profit by selling at a higher price (Figure 3.4.1).

Figure 3.4.1 Option payoffs

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Value

Option contracts exist for a period of time. During that time, the value of the option will change regularly. The intrinsic value is the money that could be obtained by exercising the option immediately—forgoing the chance at more money. The extrinsic value of an option is the value of the option that comes from holding on to it longer.

For example, consider a $1 lottery ticket that pays the winner $1 million and gives the owner an ability to flip a coin for more money. If the ticket holder wins the coin toss after winning the first million, he gets another $2 million. However, if he loses, he gives up the initial $1 million. After winning the first million, the lottery ticket is no longer riskless. The owner has the option of taking a million dollars and walking away. This is now the intrinsic value of the option. The owner of the ticket no longer has a dollar at stake—he has a million dollars at stake! The higher the intrinsic value of the option the more risk is involved.

Continuing this example, a savvy trader might realize that a 50/50 chance of making $3 million compared to losing $1 million is a profitable investment. If losing a million dollars wasn’t a hardship (maybe a multibillionaire was playing the game), it would make good economic sense to take the coin toss every time it was offered. The extrinsic value of the option is the value of not exercising the option. In this case, the extrinsic value would be approximately $500,000—a 50 percent chance of making $3 million while only having $1 million at risk.

Not wanting to risk losing a million dollars, and being a savvy trader, the owner of the winning lottery ticket might decide to sell the lottery ticket instead of exercising his option to take the risk-free million dollars. For example, the owner of the lottery ticket might decide to offer it for sale for $1.4 million. After all, a 50/50 chance at $3 million for $1.4 million is still a profitable investment. In this way, the owner of the option could get most of the benefit from the coin flip without actually exposing himself or herself to the risk of losing the million dollars.

The initial cost of the lottery ticket determines whether playing the lottery was a good or bad investment. For example, a free ticket would be a great investment. However, high up-front costs can easily transform options, and lottery tickets, into poor investments. The potential for a big payoff at low risk does not make a good investment by itself. If the up-front costs are too high, both lottery tickets and options become risk-free ways to lose money!

Typical Payoff from Trading Options

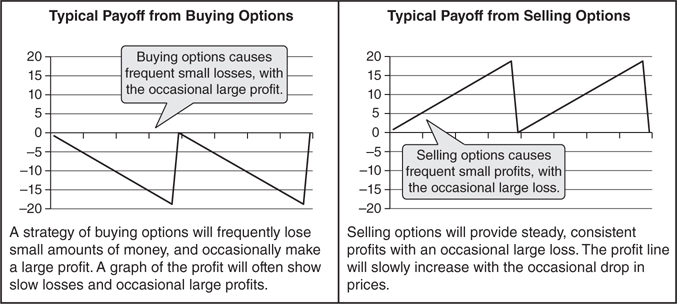

If options are priced fairly, with both buyers and sellers breaking even over the long run, a strategy of buying options loses money most of the time. This is because buying an option will occasionally return a big profit. To counterbalance that big profit, there needs to be a series of small, frequent losses. Selling options will have exactly the opposite payoff. Selling options will return steady small profits, and occasionally have a large loss (Figure 3.4.2).

Figure 3.4.2 Typical payoffs

Bid/Ask Spreads

Options, like other financial products, typically have a bid/ask spread. The price at which market makers sell to buyers (the ask price) is higher than the price where they are willing to buy options (the bid price). Relative to the size of the premium, most options have a very wide spread between their bid and ask prices. Somewhere between the two prices will be the fair price for the option.

The bid/ask spread is generally proportional to the amount of trading that is done in a particular option contract. If buyers and sellers can easily be matched up, allowing the market maker to make a low-risk profit, spreads will be very tight. However, if the market maker won’t be able to get out of the trade easily, and thinks that he might need to hold on to the option until expiration, there will be a very large spread. For example, in an illiquid option with a “fair value” of $6, it might not be uncommon to see a $2 bid price and a $10 ask price.

Becoming an option market maker isn’t particularly hard—it mostly requires enough capital to cover losses. The downside of being an option market maker is that they are always trading against informed investors. Because of the sizes of bid/ask spreads, buying and selling options in most speculative trading strategies is a losing proposition.

Why Traders Use Options

Most commonly, traders buy options as insurance. Although options may not make good speculative investments, they are a very cost-effective way to buy insurance. Having an open market ensures competitive pricing. Nothing forces traders to transact at other people’s bid and ask prices. Every trader, assuming they have assets to meet their obligations, can sell options too.

In some cases, options can be a good way to get into trades that would otherwise be too risky. A good rule of thumb is that no single decision should ever be so risky that it risks shutting down the trading desk. If a trading desk is close to its risk limit, and strongly believes in a trade, options can be a good way to take on more exposure without taking on a large risk.

Another reason that options are important is their use in investing. Many investment decisions can be modeled as financial options. For example, building a power plant gives the operator the option of burning fuel to produce electricity. The power plant operator will probably make the decision to produce electricity whenever it is profitable. As a result, options are commonly a good way to analyze any investment that involves a decision.

In the energy market, most options are written on forward or futures contracts. For example, when an option based on a forward contract is exercised early, it is the forward that gets delivered—not the physical commodity. Even if the option writer has to deliver a physical commodity at some point, the physical commodity won’t be delivered until the expiration of the forward contract.

Basing options on forwards and futures contracts reduces the benefit from early exercise. An option that can be exercised at any time is called an American option. An option that can only be exercised at expiration of the option is called a European option. In most cases, whether an option is an American or European option isn’t a big deal. It is almost always more profitable to resell the option rather than to exercise it early.

Payoff Diagrams

Traders often represent the risks of an option position by a payoff diagram. These diagrams show the final profitability of the option with respect to the price of the underlying instrument.

For example, an option might give the buyer the right to buy a natural gas futures contract for $100. At expiration, if the futures contract is worth more than $100, the option buyer will exercise the option. Even if the option buyer doesn’t plan to personally use the contract, he or she can purchase the futures contract and resell it at a profit. If the futures contract is worth $300, buying at $100 and reselling at $300, gives a payoff of $200. However, if the futures price at expiration is $50, the option is worthless. There is no good reason for the option buyer to pay $100, when the same product can be obtained for $50.

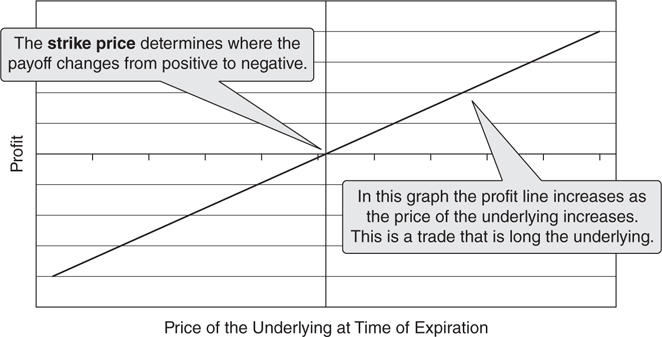

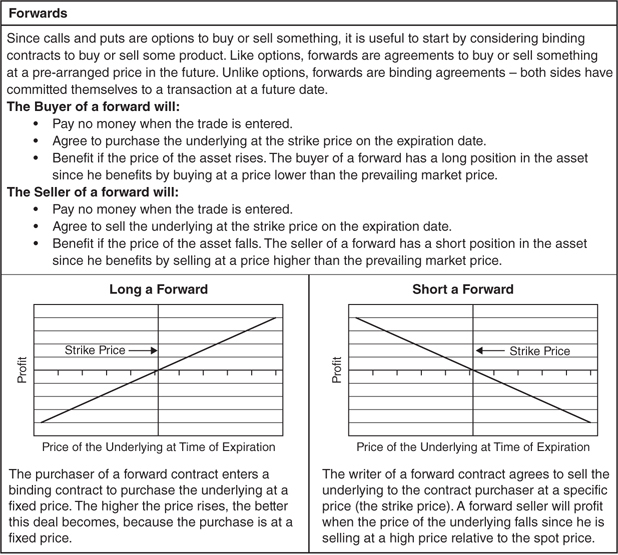

The payoff of a forward contract looks like a straight line (Figure 3.4.3). The value of the future contract varies directly with the price of the underlying product. For example, if a trader agrees to a contract to buy 100 MMBtus of natural gas at $8, that buyer loses money when prices are less than $8 and makes money when prices are above $8.

Figure 3.4.3 The payoff of a forward contract

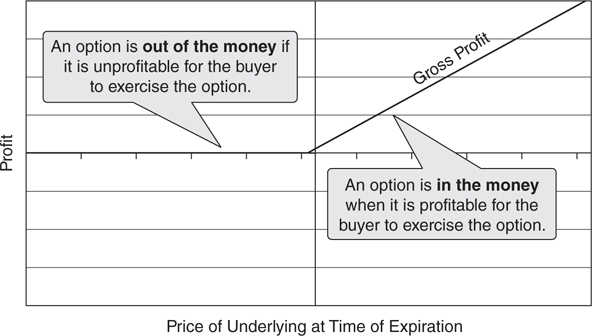

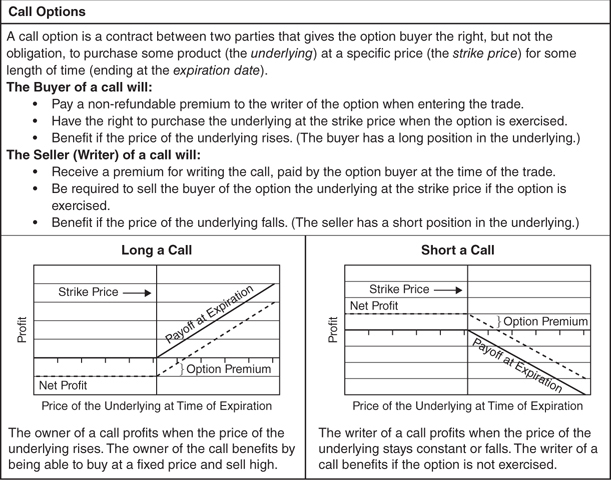

Options are agreements that allow the buyer to make a transaction at a specific price in the future but don’t require the option buyer to make a transaction. If a call option expires with the price of the underlying product above the strike price, the option is valuable. Otherwise, the call buyer will choose not to exercise the option. As a result, the payoff for an option looks like half the payoff of a forward (Figure 3.4.4). When the price of the underlying product is above the strike price, the option is profitable (it is in the money). When it is below the strike price, the option expires worthless (out of the money).

Figure 3.4.4 The payoff of a call option

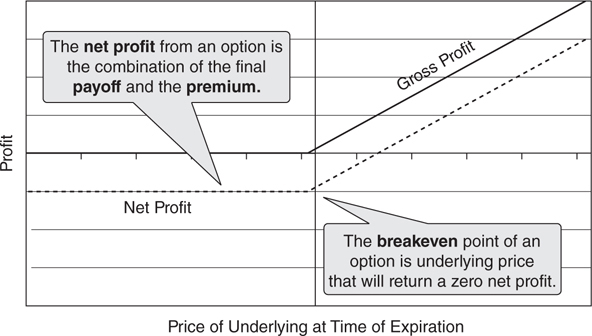

The payoff of an option is further complicated because options aren’t free—it costs money to buy an option. This shifts the payoff for the option (Figure 3.4.5). When an option expires out of the money, the option writer makes a profit. When an option expires in the money, the gross profit has to exceed the cost of purchasing the option before the buyer makes a net profit. For example, if a trader purchases an option to buy something at $100, and the option costs $20, the buyer will only make a net profit when the price of the underlying product is above $120. The breakeven price is the strike price plus the premium. The net profit is a combination of the final payoff and the premium that the option buyer needed to pay to buy the option initially. Additional details on forwards can be found in Figure 3.4.6, call options in Figure 3.4.7, and put options in Figure 3.4.8.

Figure 3.4.5 The payoff of a call with a premium

Figure 3.4.6 Forward contracts

Figure 3.4.7 Call options

Figure 3.4.8 Put options

Put/Call Parity

It is possible to combine the payoffs from multiple option transactions (Figure 3.4.9). This is the basis of many types of option trades. The most important combination of payoffs is the combination of put and call options to form forwards. The ability to combine calls and puts to form a forward forces a link between these two products. For example, by simultaneously buying a call and selling a put, a trader can replicate the payoff from owning a forward.

Figure 3.4.9 A synthetic forward

The prices of the call and put have to be identical (within the limits of a bid ask spread, at any rate). Otherwise it would be possible to reverse engineer an option payoff and make an arbitrage profit. This would be done by buying one type of option and synthetically creating an identical payoff to liquidate the position. Replicating the payoff from an option by using other options is called a synthetic option. An example of creating a long put from a short forward and a long call is shown in Figure 3.4.10. It is also possible to create other payoff structures by combining options. For example, combining a long call and a long put will create a straddle. This type of synthetic option loses money when prices remain constant but benefits when there is a large move in either direction (Figure 3.4.11).

Figure 3.4.10 A synthetic put

Figure 3.4.11 The payoff of a long option straddle