7

REMOVE COMPLEXITY

As companies grow, they become more complex. For example, at the founding of my company, SUMMi7, we had five team members, including myself. All five of us interacted with each of our customers; so, we knew what they needed and wanted. Because of this, in meetings we could always center our efforts on our customers and their needs. I had the opportunity to speak to clients directly, and I could adjust our strategies to take into account what they said.

As we grew, we needed more than five people to handle our operations. Our chief operating officer couldn’t also serve as chief marketing officer; we added managers, some frontline employees, and a sales team. Eventually, the plan is to have multiple departments, with teams of 10 or more people in each. When we get to that point, I, as the CEO, will no longer have a direct line of sight to the customer. In fact, I may be a dozen or so steps removed from the customer. And all of the other managers, the other members of the founding team, and the senior executives also will have less direct contact with customers. As a result, it will be harder for us to see them. At this level of growth, when the executive team gets together to meet and strategize, we won’t all have spoken to all of our customers, and we will be making decisions with less direct knowledge of the customer.

Greater distance from customers is just one of the many types of complexities that companies accumulate as they grow. Some operational complexity is necessary to handle growth, but too much can cause all sorts of problems—from increased costs to reduced competitiveness in the marketplace. The sum of this can ruin a business.

One layer of complexity that seeps into companies once they’ve become established is outdated technology. Technology advances so quickly that whatever software and hardware we use today will be outdated within the next decade, possibly sooner. This can be one of the greatest drivers of complexity—

as technology ages, it becomes harder for a younger, more savvy generation to plug into old processes. Companies that don’t invest in new technology tend to spend greater amounts of time training their new employees to use outdated processes. The equipment will break down, the software won’t integrate, your company ends up wasting countless hours on repairs, and overhead costs rise.

Another layer of complexity emerges over the course of decades, during which hundreds of employees will have come and gone. Each one of them will have had a unique way of doing things, often developed in response to the unique challenges that faced the company during that employee’s tenure. I’m a firm believer that the best way to do a job is the way that feels best to the person doing it, so it’s good that these employees generate their own best practices. But some of these personally customized processes will stick around long after the employee leaves. They will become dogma, something that each new hire has to learn and something that, more often than not, will feel archaic, arbitrary, and inefficient.

This is a natural part of the aging process of a company, and like aging in humans, it can’t be avoided. But just as a proper diet and solid exercise can slow or even reverse the development of plaque in your arteries, the right steps taken by a company can prevent “organizational plaque,” the needless complexities that block the flow of information and innovation. A streamlined company can better hear and respond to the voice of the customer, and it can innovate purposefully, in a way that grows profits without sacrificing core values and commitments. There are three main keys to removing complexity:

• Let the customer be your guide.

• Look for areas to simplify.

• Manage the changes that remove complexity.

Let the Customer Be Your Guide

Be aware that the customer’s wants and needs are the most important considerations in any business operational change, and simplification is no different. Doing so will cut through complexity, and give you a strong grasp on where you stand and where you need to go. It will also show you exactly what makes your company unique—and reveal the few inviolable aspects of your brand that you must protect in any efficiency crusade.

Your ability to hear your customer’s voice is key to your success. When I say “voice,” I don’t mean something general, like “feedback” or “input.” I mean this literally: you should do everything you can to actually hear what customers say, in their own words. When you can’t speak to them face-to-face, the next best thing is a word-for-word transcription, not a summary. Aggregated or summarized customer feedback can actually add complexity. For example, let’s say a customer says, “I really loved the efficiency of the delivery and the intuitive design of the product.”

If the customer relations team just summarizes that as, “Great job,” then nobody on the product development or delivery teams knows what went well. They can’t see what to improve and what to leave as is. Thus, partial information gums up the innovating capacity of the entire team.

In addition to greater clarity, when you capture information in a customer’s voice, it will help you develop an emotional connection with that customer. This is critical. Humans are emotional creatures. We make so few of our decisions based on “rational” thinking. In fact, most of our purchasing decisions are emotionally motivated. Maybe it’s a memory of always eating a certain kind of cake at your birthday parties, or a certain brand of soda pop that reminds you of your grandparents. These emotional resonances subtly drive our decision-making, especially in markets where other considerations—price, convenience, quality—are more or less uniform.

I personally make a lot of consumer choices this way. For example, my favorite dessert is ice cream. I’ve loved it my entire life, and both of my kids, as most kids do, also love ice cream. For years, we always bought the same brand of ice cream because it came in these little, single-serve, premade sundaes. The sundaes had different flavors, so you might get vanilla with fudge sauce and peanuts, or chocolate with marshmallow sauce, or strawberry with fudge. Each night after dinner, my kids and I ate our own single-serve sundaes. They were perfect because one was enough for each of us, and we could talk about our favorite flavors, taste each other’s, and compare. It didn’t require a lot of preparation or clean up. The ice cream wasn’t fabulous, but it was good, and more importantly, it was a beautiful moment to share with my kids. That’s why I bought the ice cream—not because of price or even the convenience, but for the ritual. Then the ice cream company stopped selling single-serve sundaes! Their replacement product was a little cheaper because the company saved money on packaging, but I stopped buying it because it no longer filled the same emotional need.

As a baseline, an organization should expect all employees to establish a robust, lasting connection with their customers. Then put in place the infrastructure to make it possible. There are a couple of ways to do this. In meetings with senior leadership, make it a habit to go directly to the source to find ways to improve your products and services. This involves bringing in customers and having them talk to our executives about their lives. The executives come loaded with questions—about a customer’s operations, the biggest challenges it faces, the one thing they might change about the product or its customer experience. Then we just talk to them, get to know them, and learn about their situation. This helps upper management keep the focus on the customer’s needs. Afterward, if possible, it’s also great to have that same customer meet with employees at each level of the organization—middle management and frontline workers.

Any place I’ve worked, we’ve also made it a point to send employees out to visit with customers. In the past, we’ve had frontline workers, managers, and executives go on ride-alongs with our salespeople. At Aviall, we sent out groups of frontline workers to meet with their counterparts at the airlines that buy our aircraft.

These in-person meetings provide specific, anecdotal data points about the company and its performance. They’re great because they give a well-rounded picture of the impact a product makes. But they only tell the stories of a small fraction of the customers. As nice as it would be, in very large organizations it’s impossible to speak to and meet directly with every single customer, which is why broader, more quantitative surveys still play a central role.

Conduct Useful Customer Surveys

Design a survey that communicates the true voice of the customer to employees, not just an aggregated number. Returning to the ice cream example, the company’s customer relations team might have run surveys and told the production team something like “families love the product and the sundae flavors.” Maybe those employees thought families would prefer a cheaper product, like a big ready-made sundae you could serve in scoops. This is pure speculation—I don’t know what internal metrics led to the company discontinuing the product we loved—but this illustrates why specific feedback is important.

I chose its product because “my family loved its product,” yes, but that’s not the full story. We liked it because we could each have our own sundaes with our own flavors. That bit of insight could have helped the company innovate in a more intentional way.

This highlights a larger problem with most company surveying techniques: they don’t go deep enough. The most common survey, the net promoter score, asks, “On a scale of 1 to 10, how likely are you to recommend this product/service to another person?”

If a customer would recommend, the answer is 10, if it wouldn’t, it’s 1. The net promoter score is how many advocates you have (9s or 10s) minus detractors (6 or less). That question gives you a great sense of company performance trends, but it doesn’t tell you why you’re doing well or what you’re doing poorly. This kind of questioning alone cannot fuel sustainable growth. Each product has a host of features that you engineer into it, and you need to know exactly how those features add or subtract value, either practical or emotional, in the eyes of the customer.

The most important question to ask is, “Why do you choose us over our competitors?” From this, you can compile key data points that show which features your customers connect to. That way, when you change and innovate—as any company must—you make improvements around that core connection, improvements that will make the best parts of the product shine even brighter.

This is the path taken by almost every currently dominant technology company. Think about Google, Facebook, and Twitter. Each of these started with a core service—a platform for providing information, connecting people, and so on. Each innovation and update to their software has served to make the use of their technology more intuitive. The core product hardly changes, even as the companies expand and diversify their interests.

Once the customer’s voice rings through your company halls, you need to make sure you keep that voice at the center during meetings and day-to-day operations. This requires a mindset shift—from a linear way of thinking to one that takes a 360-degree view of the customer.

Using a linear mindset, people approach problems in a predictable, straightforward way. “This is the problem, this is the goal. How do I get from point A to point B?” This inevitably leaves out important insights. For example, someone who seeks to solve a problem with fulfillment will rarely take into account the communication between the customer and the sales team or the customer and the marketing campaign. Without those considerations, an easy, obvious solution might be missed—for example, the sales team might be able to clarify expectations, or the marketing team might need to tweak its messaging to better target ideal customers.

When you craft a solution without considering all of the angles, it will likely fail to address the underlying problem and/or it will break links in other parts of the chain. This is one of the ways that complexity accrues in a company—when employees develop their own, nonstandardized, siloed solutions, it often throws the rest of the company out of alignment and spawns even more unnecessary and highly individualized systems and solutions.

This isn’t to say that you want your employees to avoid proactively solving problems—that’s the whole point of this book. But they need to take that 360-degree view of both the situation and, most importantly, the customer. This is one of the things that whiteboard meetings are great for—they allow you to convene a team with diverse perspectives so the problem can be examined from every angle.

The other solution is to simplify. Make sure that everyone understands the key metrics and how to define success in each of them. For example, if the customer feedback surveys show that customers value quality, then you can clarify everyone’s jobs and responsibilities by defining what high quality looks like at each step of the process—from product design to manufacturing, all the way through to fulfillment.

Look for Areas to Simplify

Once you’ve made sure that you can hear the customers’ voice, you can let their needs and wants guide you in the hunt for areas to simplify. You’ll find the best opportunities when you detangle three main loci of complexity:

• Points of friction

• Anchors

• Monuments

Reduce Points of Friction

Friction can arise at any point where a company interacts with customers. By friction, I mean anything that might negatively impact a customer’s experience. To find unnecessary friction, start by mapping out the entire customer journey—from the first interaction through the entire sales cycle, delivery, and follow-up; be sure to include returns and refunds. For example, let’s say that the first interaction comes when the customer orders a product online. Does the customer have to follow up with order status, or do you send status updates as you’re fulfilling the order? Does the customer get a notice of when the order has shipped? Do they have the ability to track the package? Do they receive a notice when the product is delivered? Have they received information about the product’s warranty? Is it clear how to use the product once it is received?

To reduce friction, make each step of the process as simple and intuitive for the customer as possible. Warranty claims are a great example. For a long time at Aviall, we shipped our warranty terms and conditions with the product, but we didn’t post this information online. Humans often misplace things—even important things like tax returns. Less consequential items, like appliance warranties stand almost no chance. We regularly got calls from customers who couldn’t find their warranty documents and had searched the web, but couldn’t find them there. That was an unnecessary point of friction, so we posted the warranties online.

It should come as no surprise that the most successful companies in the twenty-first century are also the companies with the smoothest customer interface procedures. Part of this is likely due to their youth. The major innovations of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century all focused on simplifying the customer’s life. Younger companies understand this. They recognize that any company that wants to compete must be a service company first. No one can rely on products alone.

Amazon is perhaps most responsible for this shift in customer expectations. It built an entire business around eliminating points of friction, offering ever faster and cheaper delivery on a massive selection of products. Amazon constantly innovates new ways to improve the customer experience, which makes it much harder for competing retailers to carve out a niche in the market.

Older companies still fall into the trap of thinking of themselves as product companies that don’t have to worry about service. For example, many car dealerships think they sell cars, not experiences. This manifests in the countless little annoyances that come with buying a car, or getting your vehicle serviced. I once had to bring my car into the dealership to get something fixed three times in the same year, and each and every time, the mechanic came out and said, “Alright, we need you to fill out this intake form.”

The intake form had all the same questions—name, date of birth, address, etc.—that I had already given the dealership, not only the first time I came into the shop for repairs, but years ago, when I bought my car. The whole time I filled out the paperwork, I felt my frustration rise as I thought, “There’s no way they don’t already have this on file.”

What should have been a 30-second conversation with someone behind a computer turned into a 30-minute intake process. What’s worse is that it happened even after I told them that I didn’t have a lot of time. They said they’d make it go as quickly as possible, but then I waited three hours for the repairs, which didn’t begin until after I’d completed the intake form. The final blow to their customer service rating came when they brought my car out. They said, “Usually, we wash it, but since you’re in a rush, we didn’t.”

I know as well as anyone how long repairs can take, and I didn’t expect them to boost me to the top of the queue or rush their work in order to get me out the door. But they certainly could have eliminated a couple of the more time-consuming steps of the repair process, including the intake, and I’m sure that they could have multitasked and cleaned my car while they serviced it or reset my expectation that it wouldn’t be done ahead of time.

Contrast this experience with what happens when someone buys a vehicle from a younger company, like Tesla. A 2018 Experian survey found that Tesla had the most loyal customer base, with more than 80 percent of new Tesla owners/leasers deciding to buy or lease a Tesla as their next car. This customer retention mark trounced the next closest competitors—Ford and Subaru—by a full 8 percentage points.

Tesla owes part of this loyalty to the quality and novelty of its product, but a large part of this has to do with Tesla’s customer service and how it reduces points of friction for customers. For one, the company controls every part of the customer experience. It doesn’t contract sales out to multiple third-party dealers like other car companies do. This gives Tesla unprecedented levels of control over the buying and repair experience, and allows it to institute uniform high standards that have become synonymous with the brand. Tesla also invests in the customer experience after the point of purchase, including ongoing funding to construct a network of charging stations for Teslas and other electric vehicles with matching ports across the United States and Europe.

Some companies intentionally build points of friction into their operating processes in an attempt to boost profits. For example, a home improvement store might sell you an extended warranty, but then make the claims process so complicated that you cannot replace or get service for the malfunctioning product without spending hours on the phone being bounced around from department to department. This is one of the most egregious forms of short-term thinking imaginable. Best-case scenario, these intentional points of friction frustrate customers, driving them to the nearest competitor and damaging your bottom line. In the worst-case scenario, this kind of friction can prove fatal to the entire company.

Many people don’t realize this, but Netflix didn’t initially gain an advantage over Blockbuster because it was more efficient, but because it offered a reprieve from one key intentional friction point: late fees. During Netflix’s early ascent, a significant share of Blockbuster’s profits came from charging late fees, which amounted to penalizing patrons. At that time, before streaming, Blockbuster was the more efficient service with stores everywhere so you could grab a movie on your way home instead of waiting for it in the mail. Netflix, as a subscription-based service, allowed you to keep the DVDs for as long as you wanted without paying a late fee. That feature of its service pulled the first customers away from Blockbuster. Streaming was merely the coup de grâce.†††

Cut Anchors

Anchors are old ways of operating or beliefs that restrict thinking. These shouldn’t be confused with a founding purpose or core competitive advantage. In the case of Blockbuster, one point of friction (late fees) had become an anchor. Blockbuster’s CEO in the early aughts, John Antioco, realized that Netflix was crushing Blockbuster because of its late fees, so he got rid of them, a move that shrank revenue by $200 million. Some factions within Blockbuster leadership, still tethered to the old mindset, got nervous about the drop in revenue during already lean times, and argued that what they really needed to do was double down on what got the brand to its dominant position in the first place—late fees and brick-and-mortar retail stores. That faction got Antioco fired, and his replacement promptly reinstated late fees. The company was out of business in five years.

But that wasn’t Blockbuster’s only anchor, even if it was the one that dragged it to a full halt. The other was that it thought of itself as a source of community. Leadership believed that people came to video rental stores because of the interactions, the staff picks, the ritual of rental. Antioco had started investing in an online streaming service, Total Access. This service required loads of capital, and the recalcitrant factions within Blockbuster thought that it wasn’t worth it because it pulled Blockbuster out of alignment with what they considered to be the core of their business—the community around the store.

Antioco recognized that a hybrid brick-and-mortar/streaming business model wouldn’t compromise Blockbuster’s purpose and that if the company didn’t shift to streaming, it would fail in the information age. His successor couldn’t see anything other than what had helped the company in the past. In the end, he made an inexcusably shortsighted decision, and steered his company to certain disaster.

Remove Monuments

Monuments are the physical testaments to anchors. They are the statues that companies build to pay homage to old ways of operating. To an outside observer, monuments usually look like trash, but the people in the organization feel a nostalgic attachment to them. Let’s look at Blockbuster once more. Those brick-and-mortar stores became monuments. They represented what Blockbuster used to stand for—a type of community, the local workers who developed a face-to-face rapport with customers. It was a place where you could run into your neighbors and say hello or make a beeline to your favorite section with your kids, grab the newest release, and buy them some popcorn or candy, maybe even their favorite action figure. Blockbuster had this monument on such a high pedestal, its leadership couldn’t see it being battered by outside forces until it came crashing down.

This is an extreme example—most companies don’t have to detonate the very backbone of their operations to remove their monuments. Still, some monuments clutter up almost every company—stuff like old fax machines, poor broadband internet, even extra staplers—any remnant of times past that doesn’t contribute to the flow of business. This sort of innocuous debris accumulates far faster than most people imagine, and it reduces both efficiency and employees’ ability to innovate. Conversely, removing monuments greatly improves efficiency and inspires innovation.

For example, when I worked for Honeywell and went to Mexico to lead the Six Sigma revolution there, part of what we did was organize the factory floor. We made sure that everything had a specific place and that only the tools and equipment we still used remained on the floor. We did this throughout five factories, and freed up a full quarter of the floor space. This number shocked us. After streamlining the physical systems, we were able to improve the factories’ output and efficiency, without paying for more space. This had cascading benefits. Because we could use our space better, we didn’t have to open a new factory to meet increased demand. Not having to open a new factory simplified and reduced the cost of our supply chain, helped us avoid regulatory conundrums, and more. As a result, we were able to expand output, with much lower capital investment.

This had the secondary benefit of improving clarity across every aspect of the workflow. Everyone knew exactly what each machine and tool on the floor did and where it should be. Employees also knew how their jobs in the assembly line fit into the overall process. This is a form of radical transparency that improves the flow of information between employees. In doing so, employees were better able to make decisions and iterate their own processes. When processes are simplified, employees know how tasks are done and can understand the connections between departments. With that deeper understanding, they can make new connections and improvements.

Manage the Changes That Remove Complexity

Now that we’ve covered the three loci of complexity to look for and eliminate from your company, let’s get into how to look for them and how to manage the change.

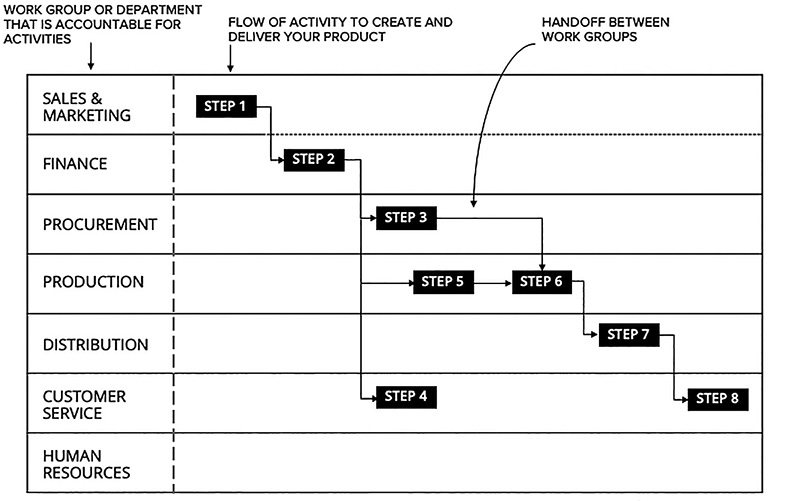

Use Swim Lane Diagrams

A great first step, something you can do tomorrow, is to create a swim lane diagram of each aspect of your company. I’ve used this tool to map out the processes within SUMMi7 to see where our handoffs are, where our costs come up, and what processes add unnecessary complexity. I also use it with clients, to help them map out processes across an entire company and projects within specific teams.

The diagram looks like an Olympic pool, where each worker in a team (or each department in an organization, depending on the scale) has a lane. In each worker’s or department’s lane, you list the responsibilities for each phase of the project, how much those actions will cost, and whether that cost is fixed or variable. Then you draw lines to indicate handoffs, either within the same lane or across lanes. As you work from left to right, it all flows and narrows until you end up with one product. Though they are not in the figure above, I like to add KPIs in each lane, so that employees know what their goals are and what success looks like for their teams. You end up with one diagram that shows the budget of each segment of the production process, for every individual or group involved, and how each one connects with the others.

With this visual element, you’ll immediately see inefficiencies, waste, and pinch points, or the areas where teams end up waiting for one group before being able to move on. When you see the pinch points, you can either smooth out the production process by slowing all of the other lanes down, or you can redeploy resources to the lane that moves more slowly than the others to speed things up. This way, you can establish a clean operating rhythm that minimizes dead time for teams between tasks.

You also can look for opportunities to consolidate actions or handoffs. For example, if one document or piece of equipment gets handed back and forth between the marketing and the sales teams four or five times, look for ways to cut that down to two or three iterations while still maintaining the same commitment to quality.

Finally, this is a great tool that enables all employees in the company, from the upper levels of management to the frontline workers, to understand how what they do and what they’re responsible for fits in with the rest of the organization. They know what’s expected of them and when, and they can see easily how dropped balls interrupt everyone else’s work. It bolsters accountability, and helps give frontline employees the bird’s-eye view necessary to make transformative iterations to their own processes while maintaining alignment with the organization.

I’ve used this diagram to lead some of my most successful battles against complexity, most memorably in 2006, when I worked for Precision Conversions, a startup that converted 757 airplanes from passenger planes to cargo planes. With help from the other leaders, and leveraging the Six Sigma playbook, we mapped out the entire conversion process on a massive, 40-foot-long swim lane diagram we put on the wall of a large training room. We documented every activity, the inputs from one department and outputs to another, and the established goals that aligned each team. We then turned that diagram into a playbook of our entire operations. We aggregated all of the actions in each lane into a single chapter of the playbook. Then we published the book on a drive shared with the entire firm, so everyone could see each team’s responsibilities and work together to streamline those. This playbook served as our baseline, and whenever a proposed change in operations came up, everyone could check it against the playbook to make sure that it wouldn’t create any inadvertent complexities or inefficiencies. This way, we managed to head off new process problems before they arose, and we had a clear understanding of where we stood, which allowed us to leap forward with greater conviction.

Once you’ve used a swim lane diagram to identify areas you want to change, you have to make those changes to reduce complexity. Convincing people to change with you is one of the greatest challenges in business. There are countless clichés about why people avoid change: because they fear the unknown, because they’re comfortable, because change carries risks. All of these, on a certain level, are true. But they are mere symptoms of a much deeper anxiety, the root fear that keeps most people stuck—fear of not being in control, and more specifically, not being as effective at your job once the change is implemented. Most people spend years mastering their craft, and change can send them back to the starting line.

So many people, especially frontline employees and middle managers, resist change because they fear that they’ll be excluded and will lose their place in shaping their own future, so they struggle to visualize what change will look like for them. Left unaddressed, this anxiety will hamstring any effort to streamline procedures. Years of companies’ myopic focus on profits has made employees skeptical of simplification initiatives. Some might think their jobs will disappear if the company finds a way to remove too many steps. For a simplification effort to work, each employee needs to buy into it and bring his or her own unique contributions and insights. If the company leaders can manage change effectively, they will empower their employees to participate and even lead the change. Employees will view the simplification effort less as a seismic shift to be wary of and more as an opportunity to make their lives easier and more rewarding.

There are two attitudes that leaders can instill in their workforces to create this outcome:

• A feeling of gratitude

• A growth mindset with a future orientation

A Feeling of Gratitude

I believe that in order to give anything, you must be grateful for what you have. This holds true for individuals and organizations. When you are grateful for what you have, for your strengths and your accomplishments, you recognize what you have. When you know what you have, then you can share it freely. This has three implications: First, it means that managers need to practice gratitude themselves before they can lead anybody else. Second, it means that they need to lead their employees and coworkers in practicing gratitude as well. And third, it means that when leading a change effort, managers must acknowledge the workers’ (and the company’s) achievements, both past and present.

Starting at the personal level, as a leader, you need to celebrate where you are. If your entire mindset is, “I’m not good enough. I haven’t done enough,” then all of the people you’re leading will feel belittled. They’ll assume that you’re judging them because you’ve made it further than they have, and you’re so hard on yourself. This doesn’t mean that you should get complacent—you just need to be gentle with yourself as you grow. Gratitude makes this gentleness possible. Not only will it help you connect with your employees, it will fuel your own growth. For example, in 2018, I decided that something I needed to work on was showing more vulnerability at work. For a while after making this commitment, I felt uncomfortable. I took a few steps back and reflected on why I was so buttoned up. It came from growing up in a household where I had to be strong and self-sufficient at a young age. I needed to take care of my friends and family, and put on a calm, stoic demeanor to do it. My discomfort with vulnerability came from this impulse. But my ability to be stoic and self-sufficient had helped me in my career, so I had to acknowledge how far this past version of myself had gotten me. I also had to consciously choose to be open and vulnerable. After all of that, I started to make progress, but it still takes work.

Humans often mirror behaviors and mindsets that they see around them—it’s why yawns are contagious. The same thing holds true for a mindset of gratitude. Leaders who really embrace gratitude and use it to authentically engage with their employees will spread the mindset of gratitude throughout their entire team, almost without trying.

Finally, the starting point of any change process has to be gratitude. Whenever I’m leading a meeting to discuss a new initiative, I give an overview of how we got to where we are, how the old system served us well, and how much we as a company or a team have achieved. This basis in gratitude shifts the entire focus of the meeting. That way, when we discuss a new initiative, it’s not as a Band-Aid or as a response to a crisis but as an opportunity to achieve more. This positive framing will always inspire more lasting engagement than negative messaging. Often and especially in periods of crisis, like when a company faces bankruptcy, managers lead with a message of fear instead of gratitude. They think that they need to make employees understand that if they don’t work hard, they will get fired. As hard as it can be, this is the moment when you need to focus on gratitude the most. Instead of outlining how poor of a position the company is in, put focus on what you can control, where you will go, and the advantages you have. If you’re going to save the company, you need people to believe that it can be saved.

A Growth Mindset with a Future Orientation

According to Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, most people have either a fixed mindset or a growth mindset. People with a fixed mindset believe that they are who they will always be. This mindset makes any sort of institutional change nearly impossible. On the other hand, people with a growth mindset believe that they can develop and that change is possible. This is the mindset you need to instill in your workforce to lead change, and you need to pair it with the proper orientation.

Everyone has a tendency to orient personal thinking either toward the past or the future. People with an orientation toward the past find energy and inspiration in legacies and histories. They feel a deep connection to old accomplishments, draw pride from them, and look to the past to develop new solutions. People with a future orientation spend their time planning. They draw inspiration from possibilities and groundbreaking ideas. I happen to be oriented toward the future—I’m always imagining the next step, looking around the corner, excited to discover or explore something new. There’s nothing inherently good or bad about either orientation, and to be successful, most companies need a healthy mix of both. Being too focused on the future can make you lose sight of what made your company unique and profitable in the first place. As I mentioned in Chapter 2, going back and revitalizing your connection to the company’s founding purpose can serve as a profound guide to your future options.

Effective change management requires a combination of future orientation and a growth mindset. Fortunately, both can be instilled with the same key strategies. Managers need to paint a compelling vision of the future to inspire people to undergo the necessary shifts. I frequently revisit this in meetings immediately after I outline the company’s current position and celebrate what we’ve accomplished. You won’t be surprised to know that I use a whiteboard, which I divide into two sections: our present and our future. I draw contrasts between the two, showing what the negative effects of continuing down our current path might be and how much we all stand to gain by making changes.

For someone to feel truly excited about the future, that person must have the ability to shape it. In these meetings, when I’m writing out the vision for the future, I may start with my own goals and the company’s goals. But then I ask employees to contribute, with questions like: “What kind of company would we have to be for you to wake up every day excited to go to work?” “What would have to be true for customers to choose us over our competitors?” “What can we do to make sure that our products or our services make a greater impact in the world?”

In doing this, we collaborate on a vision of the future, one that employees feel ownership of and are motivated to achieve. Once we have the vision, the aspiration, we can plan how to get there from where we are now. The first step is the hardest, so I make sure to draw on the board the very first thing that everyone in the room can do, and I challenge each person to accomplish it the next day. And then we are on our way.

![]()

††† Greg Satell, “A Look Back at Why Blockbuster Really Failed and Why It Didn’t Have To,” Forbes, September 5, 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/gregsatell/2014/09/05/a-look-back-at-why-blockbuster-really-failed-and-why-it-didnt-have-to/?sh=42385a221d64.