1

WHAT ALLYSHIP IS AND WHY IT MATTERS

The number one thing I have learned over years of doing this work with hundreds of companies is this: There’s no magic wand that creates diversity, equity, and inclusion. Change happens one person at a time, one act at a time, one word at a time.

It’s human nature to want quick solutions. Often companies new to diversity, equity, and inclusion believe one training will fix their problems, but that isn’t how change works. There is no training that on its own magically fixes lack of diversity, inequity, and exclusion.

In the world today, we have a tendency to believe that technology can fix most problems in our workplaces. But there is no technology that magically fixes this either. There are some technology solutions working on pieces of the diversity and inclusion puzzle; there is some training that can help people learn specific solutions to creating more equitable systems, processes, language, and structures. However, the real change happens when each of us becomes part of the solution.

That’s where allyship comes in: you and me, leading with empathy, changing how we do what we do, how we make people feel, working together to recognize and correct deep imbalances in opportunity that began centuries ago and continue today. As we reach a critical mass of allies, we create stronger and happier workplaces, companies, and industries together.

Data shows that people on diverse and inclusive teams are happier at work, we’re more innovative and productive, and our companies are more profitable.1 It’s the right thing to do, it’s the just thing to do—plus it’s good for business and it makes us all happier. When we are there for each other and support one another, we thrive together.

Who Is an Ally?

Everyone, from every background. Yes, all of us.

As a White, cisgender2 woman who lives in the United States—there are some ways I’ve been very privileged and other ways I have not. I work every day to use my privilege to be an ally for other people.3 Plus, I still need allies too.

All of us have more to learn, and we need each other. We need you. For those of us who have identities that are often underrepresented, this is an extra burden to bear on top of all the barriers we face. But I firmly believe we will not fundamentally shift society without each of us working together—being there for each other and especially for those who have less privilege than we do. No matter who you are, there is always someone who has less privilege than you who needs an ally. So take care of yourself, take time out if and when you need it, and then show up for someone when they could really use your support. I see you and I appreciate you.

What Is Allyship?

Allyship is empathy in action. It’s really seeing the person next to us—and the person missing who maybe should be next to us—and first understanding what they’re going through, then helping them succeed and thrive with us. We use our power and influence to create positive change for our colleagues, friends, and neighbors. We recognize when someone isn’t in the room who should be and work to get them in that room. And not just in the room but at the table, rebuilding that table together if it wasn’t made for them, and leading the conversations at that table.

Allyship is learning by reading, observing, listening, and hearing other people’s lived experiences. Allyship is stepping up and stepping in as an advocate—even sometimes stepping back—so that our colleagues can thrive. Allyship is also leading the change, taking action to correct unfairness and injustice. We remove barriers so everyone can rise and make sure no one is unfairly held down.

There are many terms that go hand in hand with allyship. Some say we need to go beyond allyship to being comrades, collaborators, coconspirators, accomplices, and advocates. To me, these are all forms of allyship and each is important. The work of allyship is not passive, it is active. Allies are not bystanders; allies do the work.

An alliance is an agreement to cooperate, a merging of efforts, helping each other when in need, mutually working toward a common goal. Between countries, this is often sharing weapons and supplies, fighting side by side in war—think Allied Powers in World War II. By working together, these allies won the war. Between people, often this is sharing our power and influence, working together to correct systemic barriers. Allies advocate for and with each other, we collaborate and conspire with people who have been historically marginalized to rebuild systems that are more equitable. We may start with small actions as allies, yet over a lifetime we grow into deeper actions.

What Does an Ally Do?

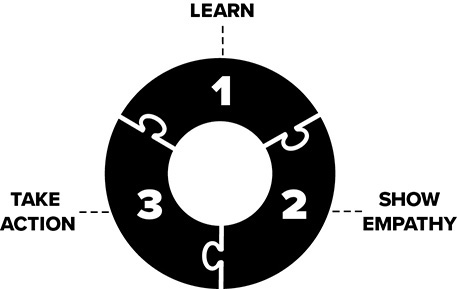

As depicted in Figure 1.1, good allies learn, show empathy, and take action: we learn to better understand each other, to become aware of unintentional harm we might be causing, to make corrections to our own beliefs and actions, and to grow as inclusive leaders. We also learn when we make mistakes (which we all do!). Good allies are always learning.

FIGURE 1.1 How to Be an Ally

EXERCISE

We show empathy for each other and recognize and value our unique experiences. We notice when people have been negatively impacted by marginalization or inequity, whether caused by ourselves, someone else, or an unfair system. Good allies are empathetic leaders, approaching people, ideas, and solutions with empathy.

We take action in ways that benefit people around us—especially people who have been oppressed and marginalized, and have faced inequity. This can be in little ways at first, then stepping into opportunities for bigger action.

This book is organized into seven steps for you to take action as an ally:

1. Learn, unlearn, and relearn. Learn about and recognize historical harm and its intergenerational impact, unlearn biases from history and cultural marginalization, and relearn from new perspectives.

2. Do no harm—understand and correct our biases. Work to change your behaviors and actions so that you don’t unintentionally harm people with biases.

3. Recognize and overcome microaggressions. Develop your awareness and empathy skills to identify and eliminate microaggressions.

4. Advocate for people. Step up and advocate for people in small, everyday ways that can make a big difference.

5. Stand up for what’s right. Intervene to stop microaggressions and support people who have been harmed.

6. Lead the change. When you’re ready, take action to lead the change in your work, on your teams, and in your workplace.

7. Transform your organization, industry, and society. Address biases and inequities in your company and in the broader world.

Allyship is not charity; allyship is being a good human. Allyship helps correct and repair centuries of people not being treated equally, create equal access and opportunity, build better companies, and establish healthier, happier workplaces and communities.

Being a good ally takes some work: each of us challenging what we have learned our whole lives about ourselves and each other, reframing success and opportunity, getting uncomfortable, and going a bit out of our way to take actions that fundamentally change lives. Sometimes we make mistakes, it’s part of allyship too—so we apologize for our mistakes, we grow as humans, and we keep learning, showing empathy, and taking action.

What Does Allyship Look Like?

Allyship can take on many forms. What’s most important is what allyship feels like and how it creates a positive impact.

Octavia Spencer and Jessica Chastain

In 2017, two friends and colleagues Octavia Spencer and Jessica Chastain were having a deep discussion about pay equity for women. Both are actresses and producers. Jessica had been a vocal proponent of gender pay equity for some time, but in this conversation Octavia shared her experience as a Black woman and talked about the pay inequity between White women and women of color. Jessica listened and learned.

“I assumed—which is the dangerous thing—I assumed a woman like Octavia Spencer would be compensated fairly for the work she’s done, and for the awards she’s received for the work she’s done,” Jessica said. “And when she told me what her salary had been, that’s what really shocked me.”4

Then she took action. Jessica was developing and producing a new film, and asked Octavia to join her on it. Octavia responded, “I am gonna have to get paid.” To which Jessica replied, “We’re gonna get you paid on this film. You and I are gonna be tied together. We’re gonna be ‘favored nations,’ and we’re gonna make the same thing.” She then wrote their equal pay into the pitch for the film. The two friends pitched the film together and sparked a bidding war with different studios vying for the production. In the end, both ended up with a salary five times higher than what they initially asked for.

“I love that woman because she’s walking the walk and she’s actually talking the talk,” Octavia said. “The thing is, people say lots of things. And when it came down to it, she was right there, shoulder to shoulder—as a producer, as an actress. It’s changed my whole perspective.”5

In response to Octavia telling their story publicly, Jessica responded on Twitter, “She had been underpaid for so long. When I discovered that, I realized that I could tie her deal to mine to bring up her quote. Men should start doing this with their female costars.”6

This story rippled through the Hollywood community as an example of how White women can be meaningful allies to women of color. “Jessica said to Octavia, ‘I got you’. . . It’s nice to go out and march, we can do that. It’s nice to wear black at the Golden Globes, it’s nice to do that. But what are we doing behind closed doors? And I gotta give our sister Jessica Chastain her props. She stood up for Octavia and put it down. And that’s how we all need to do it for each other,” said Jada Pinkett Smith.7

Other actors have also started to step up and help each other achieve pay equity. In 2020, weeks after Chadwick Boseman passed away from colon cancer, Sienna Miller, who costarred with Chadwick in the 2019 film 21 Bridges, shared in an interview that he had given a portion of his own salary to ensure she was paid what she deserved.8 Benedict Cumberbatch, Michael B. Jordan, Oprah Winfrey, Mark Wahlberg, Bradley Cooper, Chris Rock, and Shonda Rhimes have all stepped up for their colleagues in similar ways.9

Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and Peter Norman

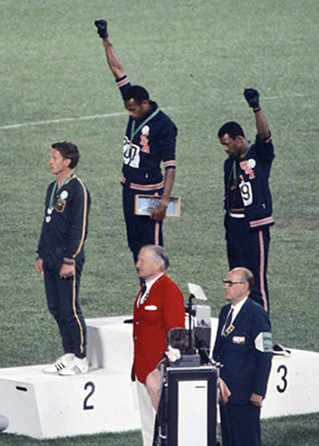

At the 1968 Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two Black athletes representing the United States, stood on the winners’ platform—and in what was seen as a radical act, they raised their gloved fists high above their heads during the US national anthem. This historic moment is captured in Figure 1.2. The two said Tommie had raised his right hand to represent Black Power, where John raised his left hand to represent Black unity. They stood shoeless, wearing black socks to represent Black poverty. Tommie wore a black scarf to represent Black pride, John wore a necklace of beads that “were for those individuals that were lynched, or killed and that no one said a prayer for, that were hung and tarred. It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the Middle Passage.”10

FIGURE 1.2 Peter Norman, Tommie Smith, and John Carlos During the Ceremony of the 200-Meter Race at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico.

[Photo credit: Angelo Cozzi, Mondadori Publishers]

Afterward Tommie stated, “If I win, I am American, not a black American. But if I did something bad, then they would say ‘a Negro.’ We are black and we are proud of being black. Black America will understand what we did tonight.”11After receiving some criticism for their actions, Tommie replied: “They say we demeaned the flag. Hey, no way man. That’s my flag . . . that’s the American flag and I’m an American. But I couldn’t salute it in the accepted manner, because it didn’t represent me fully; only to the extent of asking me to be great on the running track, then obliging me to come home and be just another nigger.”12

The third man on the platform was Peter Norman, an athlete from Australia. Peter wore the same patch that Tommie and John wore, from the Olympic Project for Human Rights. He wore it to show solidarity with Tommie and John, and to support the movement shining a light on human rights and racism at the Olympics.

All three athletes took a stand that day and paid a personal price. Tommie and John were condemned by the International Olympic Committee, withdrawn from all further races, and faced harsh public criticism. They and their families received death threats upon returning home. Peter also faced public criticism at home and was banned from future Olympics, despite repeatedly qualifying.

A few other allies stood up for Tommie and John at the time. Wyomia Tyus, a Black woman, publicly dedicated her gold medal win in the 4 × 100 meter relay to John and Tommie. The all-White Olympic crew team from Harvard issued a statement: “We—as individuals—have been concerned about the place of the black man in American society in their struggle for equal rights. As members of the US Olympic team, each of us has come to feel a moral commitment to support our black teammates in their efforts to dramatize the injustices and inequities which permeate our society.”13

That moment on the Olympic platform in 1968 is seen as an important moment in the history of US civil rights. The actions of those three men live on far beyond that moment, inspiring generations to come. When Peter passed away in 2006, Tommie and John were pallbearers at his funeral. “Not every young white individual would have the gumption, the nerve, the backbone, to stand there,” John said at the funeral. “We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat. He said, ‘I’ll stand with you.’” Tommie said, “Peter Norman’s legacy is a rock. Stand on that rock.”14

Colin Kaepernick and Megan Rapinoe

In August 2016, 48 years after Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists on the Olympic platform, San Francisco 49er quarterback Colin Kaepernick chose to sit on the bench during the US national anthem. In an interview following the football game, Colin said, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses Black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.”15 Later he explained further, “There’s a lot of things that need to change. One specifically? Police brutality. There’s people being murdered unjustly and [their murderers] not being held accountable. . . . That’s not right by anyone’s standards.”16

After public criticism of his actions from service veterans among others, Colin met with former National Football League (NFL) player and US veteran Nate Boyer to learn how to show more respect for veterans in his protest. The next week instead of sitting during the anthem, Colin took a knee along with his teammate Eric Reid. Nate stood beside them as an ally. In his statement following the game, Colin also pledged to donate $1 million to charities focused on racial inequality and police brutality.

That same day, Seattle Seahawks cornerback Jeremy Lane sat during the national anthem. As Colin continued to take a knee at game after game, other Black players across the NFL began to join the protest, including taking a knee, locking arms, or raising their fists.

Two days after Colin kneeled for the first time, US Women’s National Soccer Team star Megan Rapinoe took a knee during the national anthem at her match: “It was a little nod to Kaepernick and everything that he’s standing for right now. I think it’s actually pretty disgusting the way he was treated and the way that a lot of the media has covered it and made it about something that it absolutely isn’t. . . . Being a gay American, I know what it means to look at the flag and not have it protect all of your liberties,” Megan said. “It was something small that I could do and something that I plan to keep doing in the future and hopefully spark some meaningful conversation around it.”18 Megan is an advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights and has been active in the movement—and lawsuit—for equal pay for women’s soccer players.

In response to Megan kneeling, the next week the stadium played the anthem before the players left the locker room—before she had an opportunity to kneel. The US Soccer Federation condemned her kneeling and passed a policy requiring players to stand during the national anthem. The next month, players and staff of the men’s German soccer club Hertha Berlin took a knee in solidarity.

As a player who was getting older, who just returned from a serious knee injury, Megan’s continued protest put her career in jeopardy: “If I want people to stand up for my rights, then I have to do that, and people should do that,” she said. She faced significant backlash, including being left off the national team roster for five months. “I really thought maybe they were putting ol’ Pinoe out to pasture. I thought maybe it was over.”19 But eventually she returned to the national team after working to prove herself. “I just knew that if I was to come back from it all, I had to be so undeniable.”20

Megan’s words about her protest echo those of Colin, as well as Tommie, John, and Peter before him. “I can understand if you think that I’m disrespecting the flag by kneeling, but it is because of my utmost respect for the flag and the promise it represents that I have chosen to demonstrate in this way,” she wrote. “When I take a knee, I am facing the flag with my full body, staring straight into the heart of our country’s ultimate symbol of freedom—because I believe it is my responsibility, just as it is yours, to ensure that freedom is afforded to everyone in this country.”21

Four years later, French soccer player Marcus Thuram took a knee after the murder of George Floyd. Shortly after, English football clubs Liverpool, Aston Villa, and Sheffield United did the same. In response, FIFA—the global soccer governing body—publicly stated that such protests are “worthy of applause not punishment.” After these protests and the FIFA statement, the US Soccer Federation board repealed their ban, and its new president personally apologized to Megan. The protests continued.

Megan continued to use her voice and platform to advocate for Colin and the fight against racial injustice in global sports and in the United States overall.22

“It’s always worth it to [protest], whether people like it or not,’” Megan said. “Use your voice in whatever way that you can. I truly believe we have a responsibility to make the world better in whatever way we can do best.”23

While Megan received public criticism and condemnation for her actions initially, she was able to continue her career, eventually the ban was lifted, and she received a public apology. Colin did not have the same fate. Despite his “above-average” record as a young quarterback, no team signed him for the 2017 season.25

Colin’s actions in 2016 and beyond—with the support of allies like Megan who knelt with him—have continued to shine a light on racial injustice in the United States.

Michael Siebel and Alexis Ohanian

Ten days after George Floyd was murdered in May 2020, Alexis Ohanian Sr., cofounder of Reddit, posted on Twitter that he was officially stepping down from the board.26 He asked in his resignation that he be replaced with a board member who is Black.

“I co-founded Reddit 15 years ago to help people find community and a sense of belonging,” Alexis said. “It is long overdue to do the right thing. I’m doing this for me, for my family, and for my country. I’m saying this as a father who needs to be able to answer his black daughter when she asks: ‘What did you do?’”27

Reddit is one of the most visited websites in the world, with an incredible impact—and a history of harassment, bullying, racism, sexism, ableism, anti-Muslim, anti-Semitism, anti-LGBTQIA+ sentiment, and more on its platform. While they have done a lot of work in recent years to make the site safer, it could surely benefit from a more diverse board helping drive further safety, belonging, and innovation.

Diversity on boards is challenging to improve unless the board has term limits, someone retires, or someone steps down—so lack of representation on boards can take a generation or several to correct. Alexis taking this action allowed for an immediate change to Reddit’s board diversity. “I believe resignation can actually be an act of leadership from people in power right now. To everyone fighting to fix our broken nation: do not stop,” he said. And he further pledged, “I will use future gains on my Reddit stock to serve the black community, chiefly to curb racial hate, and I’m starting with a pledge of $1M to Colin Kaepernick’s Know Your Rights Camp.”28

Alexis’s board seat was succeeded by Michael Seibel, Group Partner and Managing Director of Y Combinator and cofounder and CEO of Justin.tv (which later became Twitch).

“I want to thank Steve, Alexis, and the entire Reddit board for this opportunity. I’ve known Steve and Alexis since 2007 and have been a Reddit user ever since,” Michael said in a statement. “Over this period of time I’ve watched Reddit become part of the core fabric of the internet and I’m excited to help provide advice and guidance as Reddit continues to grow and tackle the challenges of bringing community and belonging to a broader audience.”29

Activists and Allies in the Long Push for the Americans with Disabilities Act

In 2020, the United States celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)—a landmark civil rights act that legislated basic rights for people with disabilities. While there is a lot more work to be done—and that work is slow like most human rights work—the ADA was an incredibly important foundation for people with disabilities.

As with many legislative acts of this scale, many activists spent years, even lifetimes, laying the foundations for this legislation to happen. And as with many large-scale human rights movements, those activists needed allies to use their power and influence to ensure its success. Discrimination and oppression often prevent people from becoming leaders that have the power to create systemic change—so allyship is often necessary for systemic change to occur.

In 1986, the National Council on Disability (then the National Council on the Handicapped) issued a report Toward Independence, which recommended congressional legislation that would provide equal opportunity for people with disabilities. The council was chaired by Sandra Swift Parrino, an ally and a mother of two sons with disabilities. Sandra and her team worked with Justin Dart Jr., a disability activist (and an ally in his own right for women and minorities) to draft this report for Congress, suggesting Congress ratify “The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1986.”30

Two years later, the first version of the Americans with Disabilities Act was introduced to Congress by Representative Anthony Coelho (D-CA) in the House and Senator Lowell P. Weicker Jr. (R-CT) in the Senate. Lowell was an advocate of public policy for people with disabilities throughout his 28-year tenure as an ally and parent of a child with a disability.

That same year, the Congressional Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of Americans with Disabilities was created by Representative Major Robert Odell Owens, a civil rights activist. “The strategy was to link it to civil rights,” said Major Owens. “It was the best route to get folks to understand segregation fast. Civil rights and women’s rights had a clear history. Making the transition to rights for people with disabilities became easier because we had the history of the other two.”31

“The disability community’s success in passing the ADA would not have been possible without the opportunity, encouragement or support that Major Owens gave us. His contributions to advancing disability rights cannot be overstated,” said Yoshiko Dart, a disability activist and ally who worked on the task force. The task force was chaired by Justin and cochaired by Elizabeth Boggs, who had been a disability activist for many years as an ally. It also included 38 volunteers—people with disabilities, activists, and allies. Together they worked to make the case for legislation.

In 1989, Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA) worked with Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA) to improve the bill. Senator Harkin and Representative Coelho then reintroduced the bill to Congress. After much deliberation, compromise, and public demonstrations like the ADAPT Capital Crawl,32 the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 was passed and signed into law, as shown in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3 President George H. W. Bush Signs the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 into Law. Pictured (left to right): Evan Kemp, Reverend Harold Wilke, President Bush, Sandra Swift Parrino, Justin Dart Jr.

[Photo credit: Joyce C. Naltchayan, George Bush Presidential Library and Museum/NARA]

Sandra Swift Parrino, Elizabeth Boggs, Major Robert Odell Owens, Lowell P. Weicker Jr, Yoshiko Dart, and later Tom Harkin all worked as allies to help ensure the ADA’s success.

I share these stories as examples of what allyship looks like. In each of these cases and in all allyship, we must center the work around the people we are working to be allies for. These moments in history are about the movements and the leaders of these movements—the allies are there supporting and working with them to create much-needed change.

These are just a few very public stories of the many ways people can show up as allies, of course. Many of the allies in these stories have also needed allies in their lives. I have personally benefited from many small acts of allyship throughout my life and career: a professor I asked for a recommendation, who went beyond and hand-delivered his recommendation in person to get me an interview. A friend who helped me push through my fears of public speaking, supporting me as I worked to become a successful speaker. Another friend who taught me negotiation skills so I could better advocate for a good compensation package. Even a stranger, who offered me a place to stay when I was a broke student looking for housing in New York.

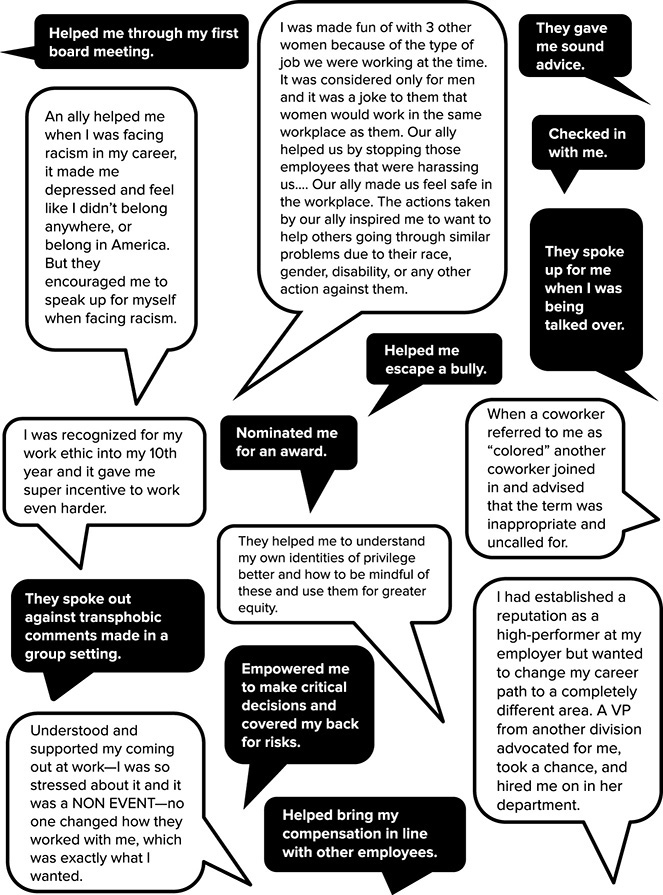

Figures 1.4 and 1.5 show just a few of the many stories people have shared with us about how allies have helped them in their careers.

FIGURE 1.4 How Allies Help People

FIGURE 1.5 How Allies Help People

EXERCISE

Why Are Allies Important in the Workplace?

Our companies have a responsibility to create inclusive cultures, build diverse teams, and correct systemic inequities in hiring, promotion, pay, and leadership. Yet we all make a mistake when we see diversity and inclusion as a side project for someone else to solve, rather than the work all of us need to do together. We are our companies—our workplace cultures and systems won’t change without all of us taking action to change them.

To improve company cultures and systems, we must take an active role in learning how our own actions affect other peoples’ abilities and opportunities to succeed and thrive, and correcting the systems and processes we use every day that may also cause harm. When you’re being belittled, disrespected, bullied, or discriminated against, it’s really difficult to create change. We can accomplish more when we work together to build a workplace where we all thrive.

This book isn’t just about White, male allyship—though that is part of it, and I appreciate all of you who are reading and taking action. This book is for all of us. Like Megan Rapinoe—a White lesbian fighting for gender pay equity and LGBTQIA+ rights—kneeling in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick to shine a light on racial injustice. Like Representative Major Robert Odell Owens—a Black senator and civil rights advocate—working for the rights of people with disabilities by forming a committee that would put together a strong case for the Americans with Disabilities Act. And Sandra Swift Parrino, Elizabeth Boggs, and Yoshiko Dart, three women who were not disabled, dedicating their careers to advocating for and with people with disabilities. Being there for each other makes a difference.

History has shown time after time that we are more powerful together than we are on our own. Together we can build healthier, happier, more innovative and productive teams. Together we can correct imbalances in success and opportunity and make our workplaces inclusive.

Why Become an Ally?

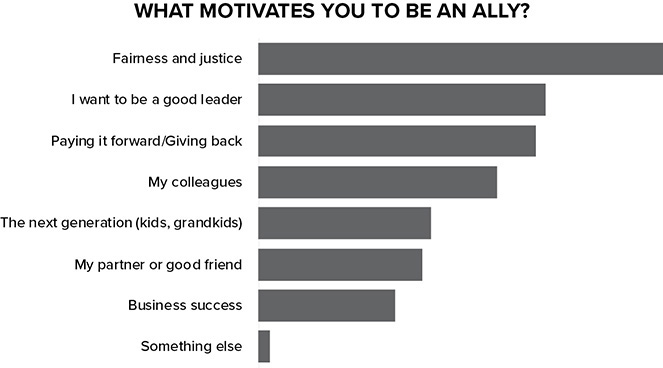

As you dive into allyship, I encourage you to reflect on your own motivation for being an ally. Reminding yourself of this from time to time can keep you motivated when you’re challenged, and can also clarify where you want to focus your allyship. Figure 1.6 shows the most common reasons people become allies from our research. Perhaps one or more of these reasons will resonate with you.

FIGURE 1.6 Reasons People Become Allies

For me, several are important drivers, but my primary motivations are fairness and justice and making the world better for future generations. Spend a moment thinking about your primary motivation.

EXERCISE

Behavior change takes time, and each person needs different input to keep themselves going on the path of change. In the following pages, you’ll find data, research, historical context, stories, quotes, and tangible, actionable steps you can take. Take what you need for your journey so you can lead the change you wish to see.

I’ve learned a lot in my journey to be a good ally over the years. And yet as I interviewed and analyzed the data from thousands of people’s ideas about allyship and advocacy, I still found surprises that challenged my assumptions. Be open to new ways of seeing, thinking, listening, and doing. What we learn can challenge some deeply held beliefs we have had for years.