5

STEP 3: RECOGNIZE AND OVERCOME MICROAGGRESSIONS

Microaggressions are everyday slights, insults, and negative verbal and nonverbal communications that, whether intentional or not, can make someone feel belittled, disrespected, unheard, unsafe, othered, tokenized, gaslighted, impeded, and/or like they don’t belong. While smaller aggressions than bullying, harassment, macroaggressions, or flat-out abuse, they can reinforce inequities and their effects can be traumatic and long-lasting. Also called microexclusions, microaggressions can be rooted in our biases and lack of understanding or empathy. And similar to biases, the key is to develop our empathy skills and become intentional so that we recognize the microaggression forming and stop it before it happens. In this chapter, we’ll learn how to recognize and overcome microaggressions, so we don’t unintentionally harm people with our own words and actions. In “Step 5: Stand Up for What’s Right,” we’ll learn ways to interrupt microaggressions when we see them.

The term microaggressions was first described in 1970 by psychiatrist Chester Middlebrook Pierce as “subtle, stunning, often automatic and nonverbal exchanges which are ‘put-downs’ of Blacks by offenders.”2 It’s now used to describe these actions against someone from any marginalized group.

Psychologist Derald Wing Sue has built decades of work on microaggressions and racism, and defines three forms of microaggressions:3

![]() Microassaults—slurs, name-calling, avoidant behavior, privileging, discriminatory actions.

Microassaults—slurs, name-calling, avoidant behavior, privileging, discriminatory actions.

![]() Microinsults—diminishing or demeaning someone’s identity or accomplishments, implications of negativity or abnormality, rudeness.

Microinsults—diminishing or demeaning someone’s identity or accomplishments, implications of negativity or abnormality, rudeness.

![]() Microinvalidations—minimizing or ignoring someone’s feelings and statements, invalidating someone’s citizenship or identity, denying racism or oppression, denying privilege exists.

Microinvalidations—minimizing or ignoring someone’s feelings and statements, invalidating someone’s citizenship or identity, denying racism or oppression, denying privilege exists.

In Sue’s work studying the effects of microaggressions across race, gender, and sexual orientation, he found the accumulated effect of microaggressions over time can be significant:

When a marginalized group member encounters microaggressive stressors, four pathways may show their negative impact: (1) biological: there may be direct physiological reactions (blood pressure, heart rate, etc.) or changes in the immune system; (2) cognitive: it may place in motion a cognitive appraisal involving thoughts and beliefs about the meaning of the stressor; (3) emotional: anger, rage, anxiety, depression, or hopelessness may dominate the person’s immediate life circumstance; and (4) behavioral: the coping strategies or behavioral reactions utilized by the individual may either enhance adjustment or make the situation worse.4

Roberto Montenegro, who studies the biological effects of discrimination, has shown that chronic exposure to microaggressions can turn into “microtraumas”—not only emotionally but also physically.5 Christina Friedlaender has shown the cumulative harm from microaggressions “can include stress, anxiety, depression, high blood pressure, insomnia, substance abuse, eating disorders, social withdrawal, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorder.”6

Each individual microaggression can be harmful in the short term, and as microaggressions accumulate daily, they can take a significant toll on someone’s life and career in the long term. People with underrepresented identities encounter microaggressions on top of the stress everyone has in work and outside of work, which is an unfair disadvantage in our work and in our lives. As allies, it’s our job to understand what “microaggressions” are, and make sure we don’t do them.

The following pages include several examples of microaggressions. This isn’t meant to be a be-all checklist of what not to do, I’ve provided it to paint a picture of what some daily microaggressions might look like, and how you can reframe your approach and work toward eliminating your own microaggressions.

You may see some things here that you do or have done. At one time or another, all good allies find ourselves making a mistake. It’s our job as allies to listen, learn, unlearn, relearn, make mistakes, apologize, and keep learning. There are lots of people whose lives we can change if we improve how we show up for them in the present and the future. So forgive yourself for what you may have done or said. Especially if you’ve done it recently, you might go back to that person or group and apologize. And then keep working hard to not do it in the future.

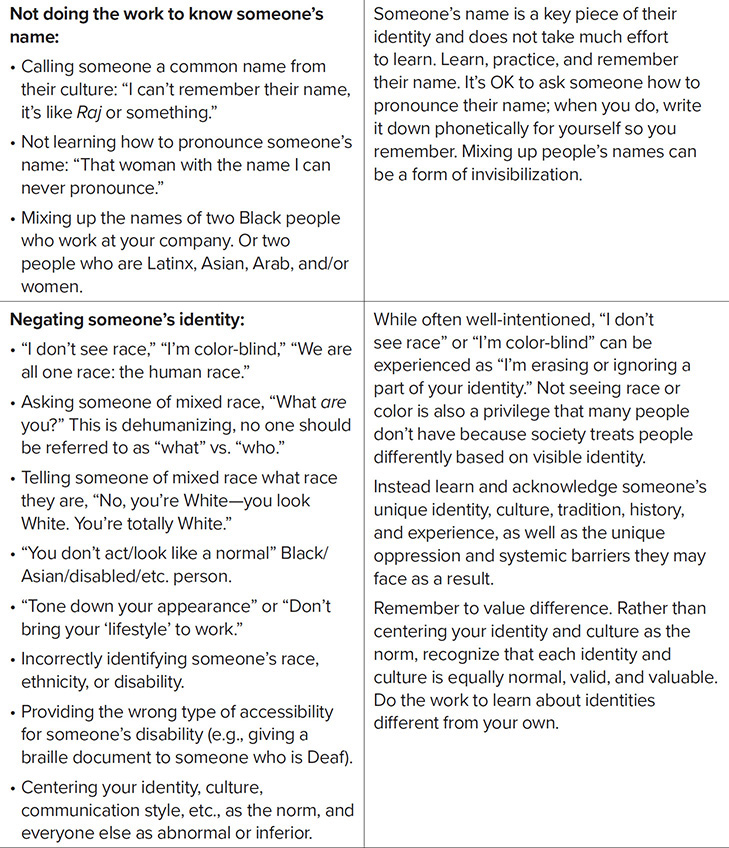

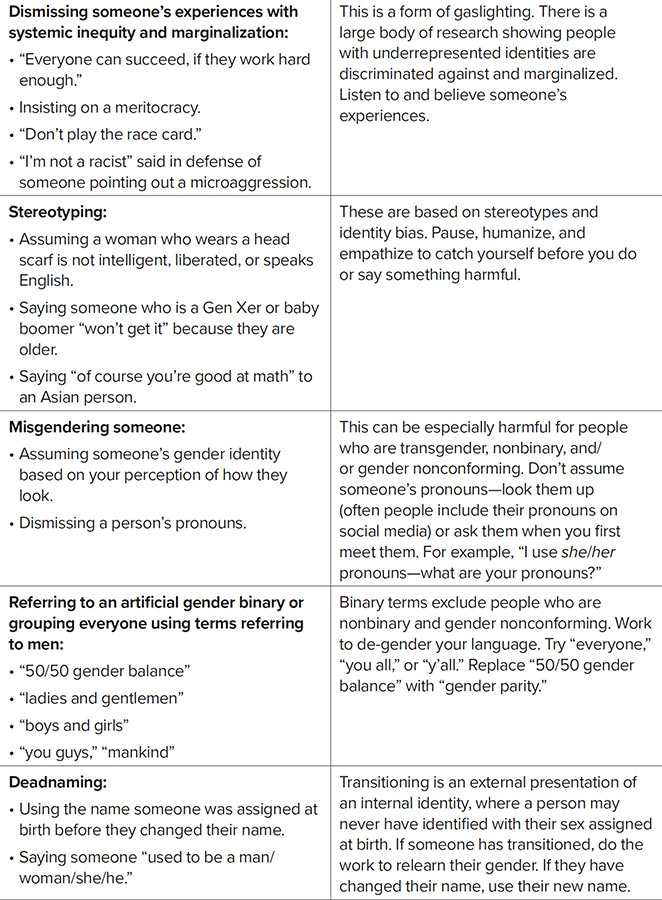

Verbal Microaggressions

Language matters; it can make the difference between shutting someone down and lifting them up. Table 5.1 shows common verbal microaggressions and some ideas to consider. (Keep in mind that language is always changing, so it’s important to check in with people to ensure terminology you’re using works for them.)

TABLE 5.1 Recognizing and Overcoming Verbal Microaggressions

Actions You Can Take to Reduce Your Verbal Microaggressions

Have you witnessed some of these verbal microaggressions? Have you experienced some of them? If you’re a person with an underrepresented identity reading this, I’m sure you could easily think of at least 10 more.

Have you said some of these phrases? Most of us have. Do the work to do no harm:

Break yourself of verbal habits that can cause harm. Choose a few microaggressions to work on, and catch yourself before or as you’re saying them. You can ask your team, family, and friends to help catch your microaggressions as you learn. If you catch yourself after saying them, work on apologizing and correcting yourself.

Learn the language people use to describe their identities. Know how to pronounce their name, how they describe their disability or religion or ethnicity, and understand their pronouns (he/him, she/her, they/them, or something else). This really matters to people. Language around identity is personal and always evolving. So if you don’t know, just ask.

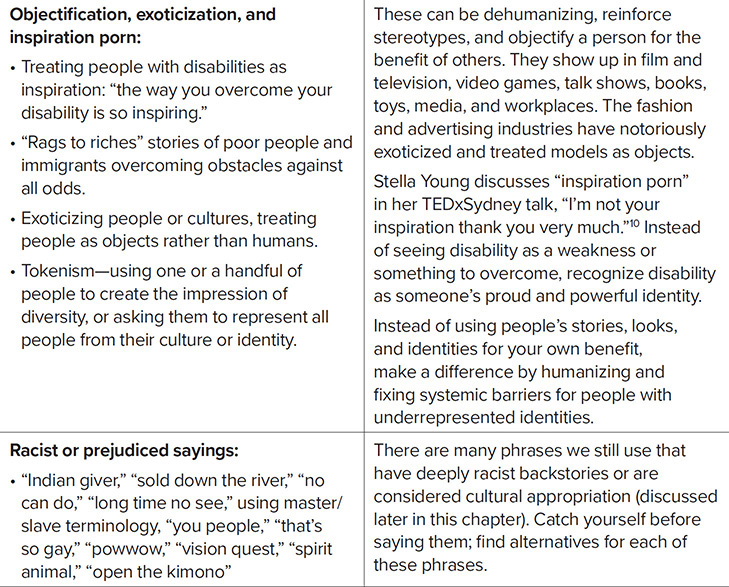

Nonverbal Microaggressions

Facial Expressions

Many microaggressions are nonverbal, so they can be subtle. When I was an undergraduate student at the University of Washington, one of my many work-study jobs was on a psychology research study. We used Paul Ekman’s foundational work in the 1970s on microexpressions to study parents’ interactions with their children.14 The study primed parents with specific facial expressions to show their kids, and mapped how those expressions affected their kids’ success on individual tests and collaborative projects.

I used a lot of what I learned studying facial expressions and Ekman’s Facial Action Coding System in my work as a documentary filmmaker. A documentarian is mostly a silent interviewer, so nonverbal feedback can be a very powerful tool in moving an interviewee where you want them to go—and giving them encouragement if they are feeling impostor syndrome, shyness, or uncertainty.

Our facial expressions can convey our feelings and thoughts. Seeing another person’s facial expressions can change how we show up. When someone is experiencing fear, nervousness, or what Ekman calls perceived “threat-to-self,” it makes a big difference whether you show them contempt or enjoyment, confusion or understanding, disinterest or interest. When I’m on stage speaking in front of an audience, I look for people in the audience to grab onto, who are genuinely listening, encouraging me, and giving me nonverbal feedback. This can affect presentations, meetings, performance reviews, interviews, and other times when someone perceives there is a lot at stake.

Ekman’s work is used by countless researchers as well as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Transportation Security Administration (TSA), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Dalai Lama (on work around compassion and emotions), and graphic animation studios (Ekman was an advisor for the Pixar movie Inside Out).

Body Language

A close counterpart to facial expressions is body language. A few key pieces of body language to keep in mind in avoiding microaggressions are closed body language and dominant power positioning. We might have closed body language or specific facial expressions due to a disability, a cultural norm, a cold room, a bias, or a reaction to something outside that moment altogether. Become aware of how you might make people feel inadvertently, and change it if you can.

Closed body language includes crossed arms, folded hands, crossed legs, turning your body away from someone, putting your hands in your pockets, looking down at your phone or the table, and putting your open computer between you and another person. These can literally put a barrier between you and the other person, whether that person is sitting or standing across from you, or they are giving a presentation in front of the room or on stage. When your body language is closed, you may be showing a person that you are closed off to the ideas or experiences they are sharing. And you might actually be more closed off to what they’re saying. Looking away, disinterested, tired, or otherwise occupied also can be felt as a significant microaggression.

Dominant power positioning includes hands on hips, hands behind your head, legs open wide while sitting (taking up lots of space), or one leg crossed perpendicular to the other over your knee. This can also include putting your arm on someone’s shoulder or wheelchair, standing over them while they are sitting down, or moving too far into their personal space.16 All can imply dominance over the other person, be very off-putting, and shut them down.

Avoidance

As shown in Table 5.2, microaggressions can also be nonverbal and passive: when we fear saying or doing the wrong thing, we might avoid someone altogether. This avoidance can have long-term effects on someone’s life. The first time I learned about avoidance was in 2016, while talking with Victor Calise, Commissioner of the New York City Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities. Earlier that year we held our Ability in Tech Summit to address DEI for people with disabilities in tech. I shared with him that for our career fair portion of the event, tech companies repeatedly said they “couldn’t” come because their teams had not been trained on how to talk to people with disabilities, or they didn’t know how to accommodate them. Victor told me avoidance is commonly experienced by people with disabilities—and since then I’ve recognized it happening with Black, LGBTQIA+, and Muslim colleagues and friends, as well as people with other marginalized identities.

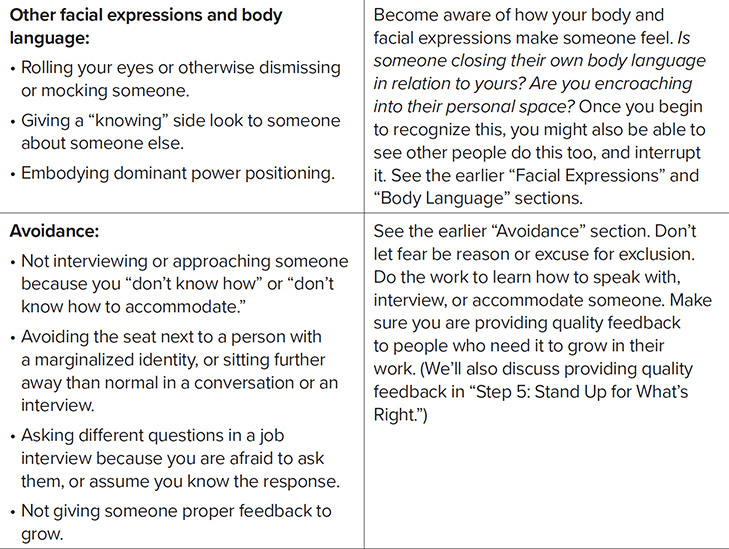

TABLE 5.2 Recognizing and Overcoming Nonverbal Microaggressions

Avoidance can also occur as a result of microaggressions. Due to discrimination, microaggressions, and lack of accessibility or inclusion—or the anticipation of these—people with underrepresented identities often avoid social situations. A 2018 Australian study found 31 percent of disabled people engaged in avoidance behaviors because of their disability.18

Actions You Can Take to Reduce Your Nonverbal Microaggressions

In addition to the considerations in Table 5.2, there is other work to do no harm:

Prime yourself. In advance of a meeting or other interaction, prime yourself ahead of time to genuinely feel the emotion you want to present to someone. Microexpressions happen in an instant, just like first impressions. Ask yourself ahead of time: How do you want to show up for this person? What do you want to learn from them, how do you want them to feel? For example, if you want someone you are interviewing to show their best self in the interview, prime yourself first with thoughts of welcoming, compassionate empathy, and inclusion.

Seek to become more self-aware in the moment. Be aware of what your facial expressions and body language are conveying. Are you conveying the message you want to convey? If not, change it if you’re able to do so. Sometimes when I’m listening to someone give a presentation in a meeting when the room is too cold, I find myself frowning or crossing my arms because of the cold. Obviously, a frown is not what I want to convey to the speaker! So I quickly put on a sweater, remove the frown, and work on giving positive, encouraging facial expressions, even nodding.

Practice empathetic listening. We teach our kids “whole body listening” and then somehow forget it as an adult. If you want to show someone you are listening and care about the conversation you’re having, open your body to the person you’re listening to: if you’re physically able to, face the person speaking, unfold your arms and legs, and put your feet flat on the floor. Try leaning into the conversation a bit to show that you’re listening. It will make a world of difference in how you both show up for each other.

Learn more about body language and facial expressions. You might check out Paul Ekman’s work on facial expressions or Allan and Barbara Pease’s work on body language. These have made a big difference in how I show up in groups and one-on-one conversations.

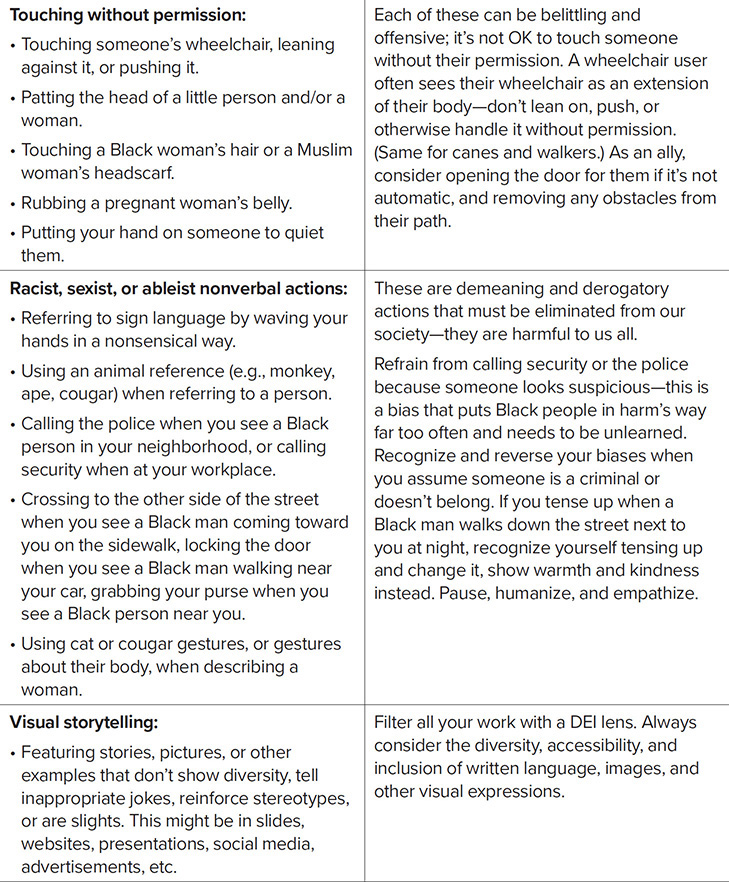

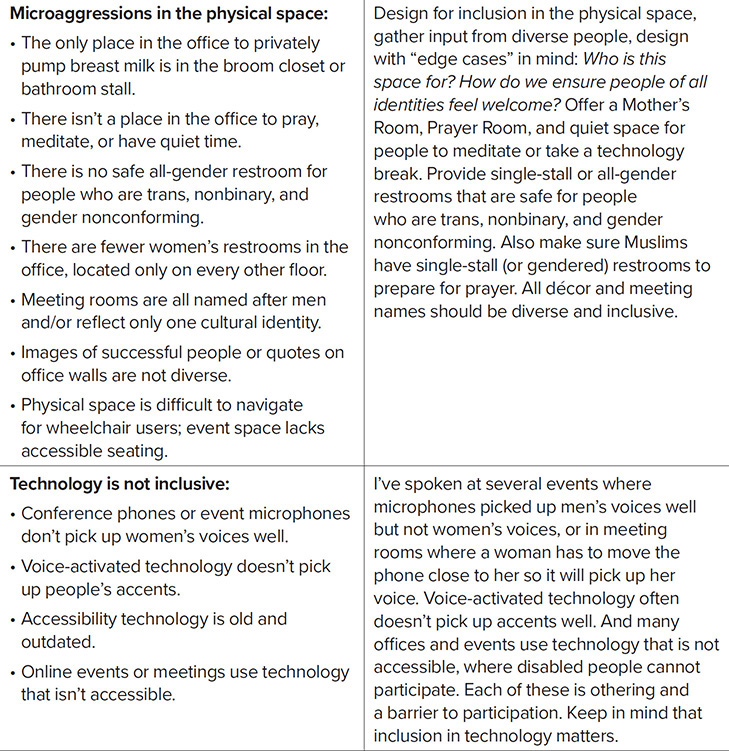

Environmental Microaggressions

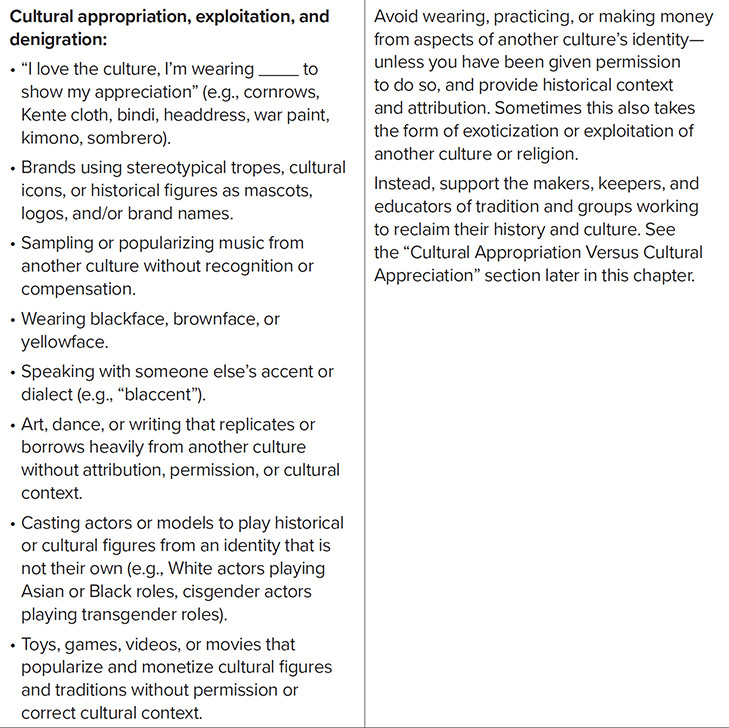

In addition to verbal and nonverbal microaggressions, there is what Derald Wing Sue calls environmental microaggressions: “demeaning and threatening social, educational, political, or economic cues” that are “manifested on systemic and environmental levels.”20 These include mascots, advertisements, media images of racial injustice and police brutality, inaccurate and belittling portrayals of someone’s identity in films and television, and lack of representation in magazines, novels, textbooks, videos, and other media. Table 5.3 shows some of the ways environmental microaggressions can manifest in our workplaces.

TABLE 5.3 Recognizing and Overcoming Environmental Microaggressions

Cultural Appropriation Versus Cultural Appreciation

When I was a child, my sister, father, and I were part of a YMCA program called “Indian Guides and Indian Princesses.” The goal of the program was to bring fathers closer to their daughters and sons. However, the activities included designing your own “Indian” leather headbands with feathers, building igloos in the snow like the “Eskimos,”21 singing “Indian” songs, and creating handmade “God’s Eyes” and “spirit catchers.” These activities were usually led by White men, reading how to do them from a handout. We took on individual Indigenous-sounding names, had a name for our “tribe,” elected a “Chief,” and in our overnight camping expeditions we even held “powwows.” The program and activities were racist, culturally appropriating Indigenous traditions, spiritual practices, and livelihoods.

We had no right to appropriate the names, rituals, attire, activities, and housing of Indigenous people. Each was taken out of their Indigenous cultural context and brought inside our White urban middle-class neighborhood as our own. I’m ashamed I participated in a program and activities that did this.

Perhaps it would have been different if the program had focused on learning from Indigenous people about their culture, language, and experiences—respecting them, valuing them, and appreciating their unique worldview. But we didn’t, these activities weren’t created so that we could appreciate Indigenous culture, they were created to bond with family members over a quaint “Indian” activity that othered and belittled Indigenous people as primitive and historical.

Apparently, the program was initially developed by Harold Keltner, a White man, and Joe Friday, from the Ojibway Nation, in the 1920s.22 Over the years, it evolved away from its arguably more authentic roots and into a program full of stereotypes, cultural appropriation, and racist tropes. In 2001, the YMCA renamed the program “Adventure Guides” or “Adventure Guides and Princesses.”23 With a quick internet search, it looks like many of these programs still have very similar programming today.24

Cultural appropriation (also called cultural misappropriation) is inappropriate, unauthorized adoption or co-opting of language, music, hairstyles, attire, fashion, art, traditions, culture, and history of another culture. The appropriator is usually someone from a majority or dominant culture who co-opts from a marginalized culture, often removing an object, culture, or tradition from its original context and placing it in the context of the dominant culture. Individual acts of cultural appropriation are generally nonverbal microaggressions. A brand’s acts of cultural appropriation are environmental microaggressions.

Appropriation of Indigenous culture permeates most regions where Indigenous people were colonized and is seen by many people as an extension of continued colonization.25 For instance, the Kansas City American football team is called the Chiefs, where celebrities bang on a drum as the crowd, with many wearing “war paint” and headdresses, does the “tomahawk chop.” Fans of the Atlanta Braves baseball team adopted the “tomahawk chop” as well, hoisting foam tomahawks.

After the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, several companies had an internal reckoning with their lack of DEI internally, as well as the cultural appropriation and racism within their brands. After nearly 100 years, Dryer’s Grand Ice Cream retired the brand name “Eskimo Pie”; B&G Foods reconsidered its racist Cream of Wheat mascot; the Washington football team retired their racist “Redskins” name and logo; Quaker Oats retired the 130-year-old Aunt Jemima brand and logo based on a racist stereotype; and Conagra reviewed its “Mrs. Butterworth’s” brand, Mars its “Uncle Ben’s” brand and logo, Colgate-Palmolive its “Darlie” toothpaste, and Nestlé its “Red Skins and Chicos” line. The band “Dixie Chicks” rebranded to “The Chicks,” New Orleans’ “Dixie Beer” rebranded, and Land O’Lakes removed the Indigenous woman from its branding in April 2020, with many more brands hopefully to follow.26 These brands are racist and sometimes sexist, appropriating, stereotyping, and perpetuating notions of enslavement and servitude. There is a museum in Michigan dedicated to racist memorabilia like these.27

As a general rule, avoid wearing, practicing, or making money from aspects of another culture’s identity unless you have been given permission to do so. If you admire and respect a culture, learn from that culture, purchase items directly from that culture, and attribute the work to the people you learned and purchased from. You also have a powerful voice that can help create change—if you see someone or a brand who is culturally appropriating, tell them so. And protest with marginalized people when they are fighting to reclaim their cultural icons.

There is a lot to digest in this and the previous chapter (Steps 2 and 3), but it’s critical that we understand and correct our biases, and that we recognize and overcome microaggressions in the workplace and in our lives so that we do no harm.

Together, we’re unlearning a lifetime of learning.

EXERCISE