CHAPTER 7

WHY THE PASSION OF THE EXPLORER IS SO POWERFUL

About a decade ago, in an effort to discover ways to overcome performance pressure, I undertook a study of the environments in which people achieved the most extreme and sustained improvements in performance. The best way to address performance pressure, after all, is to improve continually and accelerate that performance improvement over time. I explored many different environments, including extreme sports like big-wave surfing, extreme skiing, and solo rock climbing, in which participants were constantly moving beyond what many had come to believe were the ultimate limits. I also ventured into online war game environments, like World of Warcraft, where if you make the wrong move, you die (virtually).

I found something interesting. Despite the tremendous diversity of their contexts, all the people who were pushing the performance envelope had one big thing in common: each had cultivated a very specific form of passion, a questing orientation that I called “the passion of the explorer.” I define this as a drive to go where others have never ventured, to continually raise the bar of the possible.

Before we dive into to what the passion of the explorer is and how you can leverage it to move past your fear, it’s important to distinguish passion from other emotional states that are often associated with it. Passion is in a category of its own. It should not be confused with those other states, not least because they often create fear instead of helping us move past it.

DON’T CONFUSE PASSION WITH OBSESSION

Isn’t there a dark side to passion? Can’t passion degenerate into an obsession that consumes us and makes us lose sight of anything outside it? We’ve all heard cautionary tales about people who became so consumed by their passion that they lost their social standing, their meaningful relationships, and ultimately their minds as obsession gripped their every waking hour, crowding out everything else. Literature is full of such stories, as are the tabloids, from Captain Ahab’s obsession with the white whale to last night’s episode of 20/20. It’s no wonder many people fear passion.

To say that passion becomes obsession is to imply that obsession is simply a more passionate form of passion—too much of a good thing. But the passion of the explorer and obsession are differences of kind, not degree. In many ways, they are opposites.

This is much more than a matter of semantics; there are profound distinctions between the passion of the explorer and the emotions that drive obsession. Passionate explorers are committed to personal improvement in their quest to achieve more and more positive impact in the domains they have chosen. People with obsessions are seeking not to improve but to escape their very identities by losing themselves in external objects, whether they are collectibles, celebrities, a love object, or anything else that can define them. Passionate explorers are driven to overcome their personal limitations, while obsessives are seeking to escape their personal limitations.

What makes this distinction confusing is that passion and obsession can look a lot alike. Both are generated within and manifest in outward actions or pursuits, which can provide purpose and direction. Both motivate people to take risks, to make sacrifices, and to step outside conventional norms to achieve what they desire. Most importantly, passion and obsession burn within us irrespective of extrinsic encouragement or rewards. This can lead to what traditional institutions perceive to be subversive or rebellious behavior, driving passionate and obsessive people to the edges of organizations and society.

Those edges are where the crucial distinctions between passion and obsession become clear. The first significant difference between passion and obsession is the role free will plays in each disposition: passionate explorers fight their way willingly to the edge so they can pursue their passions more freely, while obsessive people (at best) passively drift there or (at worst) are exiled there. The degree to which free will determines one’s movement to the edge will greatly determine one’s capacity to succeed in that challenging environment.

Passionate explorers find edges exciting because they have a rooted sense of self. Passion inspires creation, and creators have a strong and meaningful sense of identity, defined not by what they consume (which has little or false expressive potential) but by what they make (total self-expression). For example, people who are passionate about developing new energy technologies like solar energy identify themselves as innovators in solar technology.

When I say they have a “rooted sense of self,” I don’t mean to imply that their identity is fixed. On the contrary, as creators, passionate explorers are deeply invested in constant personal, professional, and creative growth. They are constantly seeking to develop and diversify their talents in order to keep their creations innovative and their passion dynamic, sustainable, and alive. Those innovators in solar technology are constantly evolving their identity based on their latest accomplishments in pushing the frontier of solar technology performance.

Through the challenge of creation and the innovative disposition demanded by the ever-shifting edge, passionate people expand their personal boundaries, helping them achieve their potential. Passion gives them the energy and motivation to work hard—and joyfully.

In contrast, obsessive people have a weak sense of identity, because they displace their sense of self into the object of their obsession. Consider, for example, the obsessed sports fan who can only talk about her team or the infatuated fan of a rock star who builds his life around the star’s tours and tabloid coverage, even though he and the star never even meet. (This becomes a strange form of self-obsession, which is why obsessive tendencies are frequently associated with narcissism.) Far from the joyful effort and striving inspired by passion, obsession is a strategy of escape. In conflating their identity with their object of fascination, obsessives not only can forget their inner selves but also insulate themselves from the challenging world around them.

The obsessive person’s focus is narrow because such a person is less interested in complex growth than singular direction. Obsessive personalities may be driven to create, but their lack of determination to grow as people constricts the scope of their creativity. Rather than realizing their potential, they restlessly search for ways to compensate for their sense of inadequacy.

It’s no accident that we speak of an “object” of obsession but the “subject” of passion. Obsession tends toward highly specific focal points or goals, whereas passion is oriented toward networked, diversified spaces. Objects of obsession are often quite narrow—for example, using a specific photo-editing tool, developing enhancements to a specific product, or developing new art around a specific pop culture character or icon. Subjects of passion, in contrast, are broad—for example, using digital photography to explore new perspectives, innovating within a broader category of technology, or experimenting with a certain genre of pop culture. Given this broader focus, passionate people thrive on knowledge flows to stimulate innovation, achievement, and growth.

Because passionate people are driven to create as a way to grow and achieve their potential, they are constantly seeking out others who share their passion in a quest for collaboration, friction, and inspiration. Because they have a strong sense of self, passionate people are well equipped to form relationships. They present themselves in ways that invite trust: they have little time for pretense and are willing to express vulnerability in order to receive the help they need for achieving their own potential. Because they are passionate, they are willing to share their own knowledge and experience when they encounter someone who shares their passion. They are also intensely curious, seeking to understand the other passionate people they encounter in order to better see where and how they can collaborate to get better faster.

In contrast, obsessive people hide behind their objects of obsession. They care most about those objects, not others or even themselves. As a result, obsessive people are hard to get to know and trust, because they exhibit minimal interest or curiosity regarding the needs or feelings of others and share little of themselves. One of the hallmarks of obsessive people is a tendency to rant endlessly and often repetitively about the same thing, rarely inviting commentary or reaction.

The key difference between the passion of the explorer and obsession is fundamentally social: passion helps build relationships, and obsession inhibits them. Passion draws other people in; obsession pushes them away. Therefore, you can differentiate between passion and obsession by asking this question: Is the person developing richer and broader relationships, or is the person undermining existing relationships and finding it difficult to form new ones?

Passion creates options, while obsession closes them. Passion reaches outward, while obsession draws inward. Passion positions us to pursue the opportunities created by the Big Shift, while obsession makes us oblivious to the expanding opportunities around us.

DON’T CONFUSE PASSION WITH AMBITION

Many people equate passion with ambition. Once again, it’s a question of semantics, but I would suggest a key distinction, at least when it comes to the passion of the explorer. People driven by ambition tend to be more focused on personal success and the extrinsic rewards that success provides—the higher salary and the more prestigious title. For the passionate explorer, it’s enough to achieve a higher level of performance or create more value for others in the domain.

In their quest for those extrinsic rewards, ambitious people trumpet their strengths and talents to the people around them. Since they play to win, they hew closely to the rules of the game, rarely thinking outside the box. Passionate explorers, in contrast, are driven to challenge the rules when they see an opportunity to have an even greater impact by innovating. Ambitious people use the people around them as stepping-stones, while passionate explorers constantly reach out to the people around them and ask them for help. Passionate explorers build trust, while ambitious people arouse suspicion, because they are so clearly focused on their own advantage. Ultra-successful entrepreneurs like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Steve Jobs were clearly motivated by intrinsic rewards as well as the material rewards they ultimately accrued. All of them continued to learn, take risks, and wrestle with big challenges long after they had attained status, wealth, and the other external markers of success.

A TAXONOMY OF PASSION

So much for what passion is not. What is it? Many would say passion seems to be all about emotion, especially excitement; to be passionate is to be deeply excited about something or someone. The word is often used to mean the opposite of reason, which is the use of our intellect to understand something. For those who are deeply embedded in rationalistic cultures, that renders passion deeply suspect. In this view, passion is a distraction and can lead us to do irrational things, so we need to stay focused on reason and the mind, not letting our emotions get in our way.

I agree that passion is about emotion, but I would strongly challenge the view that passion always stands in opposition to reason and that it somehow undermines what we can achieve with it. In fact, I would argue that when we put passion and reason together, we can achieve much more than we can with reason alone. While I fully accept the power of reason (something that has shaped my life), the question the rationalists tend to dismiss or avoid is what motivates us to apply the power of reason to achieve new insights. Saying that reason motivates us to apply the power of reason is a tautology. What inspires and sustains the pursuits of the lover and the scientist alike is passion.

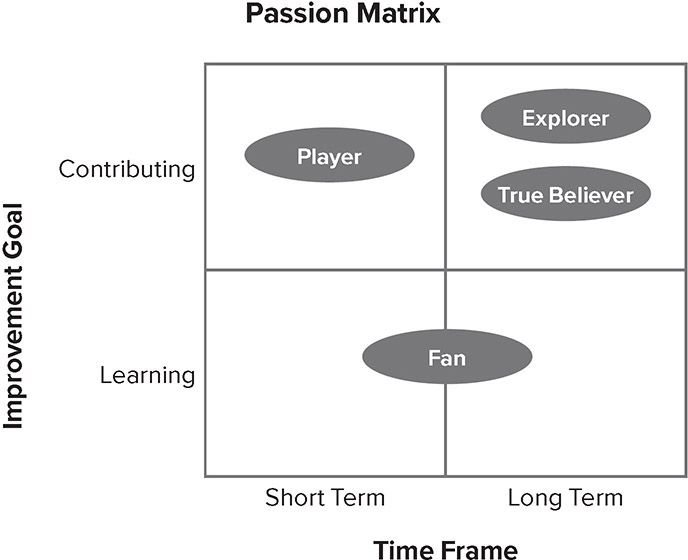

In fact, passion is many things. A long time ago, I developed a taxonomy of passion to help build a shared understanding of its different forms and to highlight what is distinctive about the passion of the explorer. My taxonomy of passion reveals some of the different types of passion. In classic consulting fashion, it’s a two-by-two matrix, focusing on two key dimensions: improvement goal and time frame (see figure). These categories of passion are not hardwired. The boundaries can be fluid, and one form of passion can evolve into other forms over time.

Along the vertical axis, we measure the improvement goal as being more about learning or contributing. Learning is finding out about the domain that is the subject of the passion, while contributing is about making a difference to that domain. The greater the passion, the greater the desire to leave the domain a better place than you found it. Of course, if your focus is on contributing, you are still driven to learn, but it’s no longer learning for the sake of learning. Contributing leads to still more learning as you begin to see which efforts produce the largest impacts and which efforts produce the least.

The horizontal axis measures the time frame of commitment to the domain. A person can commit for just a short period, or there could be a long-term commitment.

As we explore these two dimensions, many different forms of passion emerge. Though I will have the most to say about the passion of the explorer, it’s worth spending a little time on each form, since understanding the different kinds of passion helps us understand the unique potential of the passion of the explorer.

Passion of the Fan

Let’s start with the passion of the fan. I’ve situated it in the lower half of the matrix, because for most fans, the passion is not about contributing to the domain so much as learning about it. We all know people with this kind of passion. They develop a deep interest in a person, team, idea, or discipline and set out on a quest to learn everything they can about it. Whenever they learn something, they get really excited, but their passion is insatiable; before long, they are off in pursuit of five new questions.

Fans generally seek each other out to ask each other questions and share what they’ve learned. There’s never enough time to cover everything; conversations go on late into the night. If the passion is for a sports team, they go out of their way to see the team in action, even if it means traveling to distant cities. But when they go to the stadium, they stay in their seats; they don’t want to go out on the field. Their passion is to learn about the players and the game. The only real contribution they want to make is to increase awareness of the domain for others, so that they too can become fans.

Passionate fans can be found in sports, music, theater, and virtually every other domain of knowledge or activity. For many years, I was a passionate fan of paleontology. I couldn’t read enough books on the subject, and I had huge admiration for paleontologists like Mary Anning, Barnum Brown, Edward Drinker Cope, and Othniel Marsh. But I never once went out looking for fossils.

I’ve put the passion of the fan in the middle of the lower half of the matrix because it’s not always clear how long the passion will last. With sports fans, the passion is generally long-lasting. Once they develop the passion, they’re in it for decades. But others, like teens with the latest boy bands, become passionate fans for a period of time and then get bored and move on to something else.

Passion of the Player

If we move into the upper left quadrant of the matrix, we find a very different kind of passion, something I call the passion of the player. We’ve all met people with this kind of passion. They get deeply immersed in a topic or domain (or sometimes a person or a team) and not only want to learn more and more about it, but also are driven to create something or contribute something to the subject themselves, in a way that goes beyond mere conversation or discussion with other fans. They might want to pursue original research to discover some entirely new facts, write about the subject, build something, write fan fiction, or organize a fan club. In all these cases, the urge is to make a difference, not just learn about or talk about the subject.

Players can be fans who develop a motivation to create, as in the research of Henry Jenkins, a prominent media scholar who wrote about participatory cultures. Jenkins, in his book Convergence Culture, describes players coming together “to construct their own culture—fan fiction, artwork, costumes, music and videos—from content appropriated from mass media, reshaping it to serve their own needs and interests.” Other examples of fans becoming players involve commercial products. Some fans of Lego building blocks become so passionate about this toy that they actively engage with the company on the design of next-generation products.

But there’s a catch. Players have a hard time sustaining their commitment to a particular subject or domain. They get deep into it and make awesome contributions, but then they get distracted by something else and dive into that with equal vigor. This pattern repeats over and over again; nothing seems to hold them for very long.

Of course, some of these players do develop a long-term commitment to their domain. Their passion may evolve into the passion of the explorer. These categories of passion are not hard-wired. The boundaries can be fluid, and one form of passion can evolve into other forms over time.

Passion of the True Believer

As we move into the upper right quadrant of the matrix, we find a very different kind of passion: the passion of the true believer. True believers are deeply committed to achieving impact in a domain for the long term. They clearly see their destination in great detail and, perhaps even more importantly, the path they’ll need to take to reach it.

The journey will be long and challenging but also an exciting, and true believers are committed to staying the course, doing whatever is necessary to accelerate movement down the path for themselves and for others. True believers work hard to draw others into their journey. But there’s a catch. They cannot tolerate questions about either the destination or the path. These are a given, and to debate them would be simply a distraction and a waste of time. If you want to make the journey along the already-defined path, the true believer will welcome you with open arms. But if you ask uncomfortable questions, you’ll quickly find yourself expelled from their inner circle.

Fundamentalist religions tend to cultivate the passion of the true believer, but true believers can be found in many domains. A lot of the entrepreneurs I run across in Silicon Valley and elsewhere are true believers. There are certainly true believers in large enterprises, schools, and governments as well.

Passion of the Explorer

I’ve saved the best for last—the passion of the explorer. People with the passion of the explorer bring together three elements. The first is a commitment to a domain, usually one that is broadly defined. They are excited about the prospect of having a growing impact in the domain over a long period of time, often a lifetime. That domain could take many forms. It might 140be an area of knowledge, like astronomy or sociology. It could be an industry or area of practice, like marketing or medicine or manufacturing. It could also be a geographic community or a craft, like gardening or woodworking. Whatever the domain, passionate explorers are not in it just to learn about it. They are committed to making more and more of an impact in the domain.

Here’s a key difference between this type of passion and the passion of the true believer: Explorers do not have a detailed view of their ultimate destination but instead are inspired by a high-level view of an opportunity within it. Explorers also have little sense of the long-term path they will pursue. They are excited by the ability to evolve their own path as they go and the anticipation of their surprise and wonder when they find out where the path ultimately takes them.

A second characteristic of the passion of the explorer is what I call a questing disposition. It manifests when the explorer is confronted with unexpected challenges. Most of us dislike unexpected challenges, and many of us fear them. We want to get on with our plans and programs. Sometimes we ignore challenges in the hope they will go away if we wait long enough. Eventually, we find ways to work through them, but our goal is to get back to the activities we were already pursuing.

People with the passion of the explorer have a very different response: they get excited. They say to themselves, “Here’s an opportunity to do something that hasn’t been done before—to develop even more capability and have more impact than previously expected.” What could be more exciting than that?

This questing disposition is a key factor in overcoming fear. When we meet a challenge we’ve never seen before, a very natural tendency is to be afraid. People with the passion of the explorer certainly experience fear when seeing a challenge for the first time, but they are motivated to move forward in spite of that fear. In fact, people with the passion of the explorer quickly get bored and frustrated if things get too easy. When that happens, they will often move to an environment where they will have more dragons to slay and can achieve more impact.

The third quality of the passion of the explorer is what I call a connecting disposition. Self-absorbed and individualistic as we often are, most of us tend to close ourselves off when we are confronted with a problem, retreating behind closed doors to figure out what to do. We reemerge when we’ve come up with an answer. Passionate explorers have a very different response. Their first instinct is to try to figure out who else might share their passion or have relevant expertise and ideas that can help them come up with a faster and better answer than they could on their own. As a result, they are constantly connecting with others.

One of the things I discovered as I studied people with the passion of the explorer is that they tend to come together in the creation spaces I described in Chapter 5. If you spend time with big-wave surfers, you’ll find that they tend to have deep, trust-based relationships with a small group of other surfers who typically visit the same beaches on a regular basis. Similarly, players in online war games like World of Warcraft typically form small groups.

Passionate explorers build trust as quickly as they do because they don’t put up a façade. They freely admit their vulnerability, which helps them move past fear. Think about it: when we try to solve problems on our own and fail, we often fall into a vicious cycle of defeat and self-loathing. We become trapped in our own heads and consequently become much more risk-averse. But if we can connect with others who share our excitement about addressing the challenge, we can move past our fear together.

Fitting Romance into the Matrix

You may think it’s strange that I’ve written so much about passion without considering its romantic dimensions. Is there a place on the grid for the passion that arises in our relationships? There isn’t, because truth be told, our passion for our partners can mimic many of the other types of passion I’ve discussed. There’s the passion of the player, who avoids long-term commitments but has a deep desire to engage for a period of time. There’s the passion of the fan, in which the goal is to learn as much as possible about the partner, but there is scant interest in helping the partner achieve more of his or her potential. There’s the passion of true believers, who believe that they know their partner better than their partner does and that they know exactly what their partner should be doing to achieve their potential. Finally, there’s the passion of the explorer—someone who is excited about the opportunity to learn more about their partner and to help them achieve more of their potential over time.

For those who believe that passion is experienced at the beginning of a relationship but then naturally dissipates over time, I recommend Can Love Last? by Stephen A. Mitchell, one of the most romantic books I have ever read. He argues convincingly that, by adopting the passion of the explorer (although he doesn’t use this term), one can nurture and sustain passion in a relationship for a lifetime. The passion of the explorer doesn’t just enrich our relationships with our partners; it can enrich all our relationships, including those with our children, our broader families, and our close friends.

The Importance of the Passion of the Explorer

The reason why the passion of the explorer is important goes back to the context for this book—mounting performance pressure and our natural human reaction to it, which is fear. Fear also has some predictable consequences: increasing risk aversion, shortened time horizons, adoption of a zero-sum view of the world, and eroding trust. These are all understandable but also dysfunctional. They pull us into a vicious cycle of increasing pressure and an increasing inability to respond to that pressure.

The passion of the explorer can change all that, helping us achieve far more of our potential by accelerating learning through action, which is a very different form of learning than reading a book or listening to a lecture. Focusing us on a long-term commitment to increase our impact in a specific domain, the passion of the explorer inspires us to constantly seek out new challenges as opportunities for development. It motivates us to connect with others and to foster growing networks of trust-based relationships. In short, it moves us from isolated passivity to collective action. Most importantly, it helps us move beyond our fear by drawing out hope and excitement.

PASSION AND REASON

While passion is a key to overcoming fear, we cannot fully leverage it without reason. Passion gives us agency by generating energy and a sense of freedom. Reason gives us needed structure by imposing constraint and discipline. Without structure, agency makes us an aimless whirlwind of activity, constantly distracted by the bright lights and unable to maintain forward movement. Without agency, structure makes us an inert mass, sinking deeper into the ground below, seeing the world but unable to explore it. In his classic book The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran put it eloquently:

Your reason and your passion are the rudder and the sails of your seafaring soul.

If either your sails or your rudder be broken, you can but toss and drift, or else be held at a standstill in mid-seas.

For reason, ruling alone, is a force confining; and passion, unattended, is a flame that burns to its own destruction.

Therefore let your soul exalt your reason to the height of passion, that it may sing;

And let it direct your passion with reason, that your passion may live through its own daily resurrection, and like the phoenix rise above its own ashes.

Benjamin Franklin also expressed this sentiment more succinctly: “If passion drives you, let reason hold the reins.”

We can gain more insights into the tight relationship between passion and reason by looking at five things that need to come together before we can achieve our full potential: focus, action, relationships, friction, and the framing of powerful questions and answers.

Focus

We need to be able to carve out specific domains we can focus on to achieve world-class performance. When we spread ourselves too thin, we risk being superficially engaged in too many areas to achieve world-class performance in any of them. But how do you pick the domain that offers the greatest opportunity to excel?

Passion provides the key. If you are not passionately engaged in a particular domain, you are unlikely to invest the effort and energy required to achieve mastery and distinctiveness. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell argues that successful people generally invest considerable effort over time—at least 10,000 hours—to master their domains. In a world of constant change, one could make the case that 10,000 hours is just table stakes; sustained excellence demands continued investment. It is very hard to sustain that kind of investment over years without passion to provide the motivation. If we rely solely on reason to select an appropriate domain, we may have a compelling logic, but logic alone is unlikely to sustain us as we begin to encounter obstacles and distractions and experience the fear of failure. Many people talk about the need for grit or discipline, but people with the passion of the explorer are excited about investing this time and effort to develop themselves. They don’t have to force themselves to do it.

Once you have chosen a domain to focus on, reason provides a valuable way to frame questions and test the experiences you accumulate as you explore it. Reason helps you choose the most productive directions to pursue, and it helps you solve the difficult puzzles you will encounter.

Action

Having chosen your domain, you must engage with it and explore its furthest reaches (dare I say, edges?). It is not enough to sit in an easy chair and contemplate; you must roll up your sleeves and dig in to really experience the textures and particulars that give you the deepest insights into what is really going on.

Leaving that easy chair to venture into unknown territory presents real risks, and reason alone rarely helps us overcome our fears. In fact, it can deceive us into believing we can process information about the domain at a distance, keeping our attention focused on the forest, without the distraction of all those trees.

Passion will have none of that. It demands your full engagement and will settle for nothing less. It propels you forward, giving you the energy and courage to welcome any challenge as an opportunity to test yourself, regardless of the risk.

Once again, though, reason provides a welcome companion on the journey. It helps you reflect on your experiences and discern the patterns that emerge from seemingly random encounters. Reason allows you to see the themes that make the particulars less particular and part of a more coherent whole. It gives you powerful tools to make sense of rapidly evolving landscapes and to zero in on the underlying forces that drive and shape their evolution.

Relationships

To fully experience a domain, you must engage with people in ways that go much deeper than casual conversation and allow you to view things through different sets of lenses and build a shared understanding of the domain. Your shared passion helps you forge these important connections.

The passion of the explorer inherently drives us to connect with others. It provides capacity for empathy. It draws out the stories that are the first and often most powerful expressions of the new knowledge emerging on the fertile edges of your domain. Our research at the Center for the Edge showed a clear relationship between a worker’s level of passion and degree of connection with others through a variety of avenues, including conferences and social media. Those who are motivated purely by reason are likely to find themselves less connected and therefore at a disadvantage relative to those who are connected through a shared passion.

At the same time, reason plays a role in forging and cementing bonds. A shared commitment to reason can help people overcome deep differences in experiences, assumptions, and perspectives. It can help build a shared understanding that offers access to the tacit knowledge each participant brings to the table. It also provides a powerful framework that lets you sift through idle distractions and zero in on what’s truly relevant.

Productive Friction

Participants in the quest to achieve better outcomes should challenge each other. These challenges are productive friction when their intent is not to establish dominance or put each other down, but rather to create better outcomes, drawing upon a spirit of mutual respect and commitment to the quest. That spirit makes friction productive.

The passion of the explorer provides a fertile ground in which productive friction can emerge and flourish. Having a shared passion creates the trust that allows people from different backgrounds and experiences to engage with each other even when some of their most cherished assumptions are being called into question. Being on a shared quest to find the most creative ways to drive performance to new levels opens participants to new approaches that can deliver performance breakthroughs. If passion provides the context for fruitful debate, reason provides the toolkit needed to address and resolve differing views.

Framing Questions and Answers

Passion frames the most powerful questions, and reason frames the most convincing answers. This is another way to express the mutually reinforcing effects of passion and reason. As Claude Helvetius, a French philosopher during the Enlightenment, observes, “It is the strong passions alone that prompt men to the execution of . . . heroic actions, and give birth to those grand ideas, which are the astonishment and admiration of all ages.” Helvetius gave one of the essays in his book Essays on the Mind the lengthy but pointed title “The Superiority of the Mind in Men of Strong Passions Above the Men of Sense.” In it, he asserts, “It is, in effect, only a strong passion, which, being more perspicuous [sic] than good sense, can teach us to distinguish the extraordinary from the impossible, which men of sense are ever confounding; because, not being animated by strong passions, these sensible persons never rise above mediocrity.”

In short, passion prompts us to ask the difficult and creative questions that “sensible” people would never think of asking. Framing the right question is one of the most powerful learning tools we have. With the right question, reason can help us generate powerful answers, but the question focuses the tool of reason and ultimately provides its power.

Reason and passion work together to overcome our fear of the unknown. Reason gives us confidence that we can handle any question, no matter how disturbing it might be. Passion provides the questions, setting in motion a virtuous cycle in which the better we get at wrestling with inspiring questions, the more we want to do it. As it plays out, our fear will naturally recede into the background, opening up a space in which we can become stronger and wiser.

TO FIND YOUR PASSION, YOU HAVE TO LOOK

If passion is so powerful, how do we find it and cultivate it? That is the focus of the next chapter, but for now, it is important to stress that the first important step is simply to decide to look for it.

Unfortunately, we live in cultures, societies, and institutions that conspire to discourage us from seeking our passion. We are regularly counseled to focus on acquiring skills that will be in high demand or to identify a natural talent we already have and choose a career in which it will be useful. The unstated assumption is that we are at risk of not earning a decent living, so we need to focus on building our skills. Emotions are a distraction.

On the contrary, we need to understand that emotions are the key to our ability to achieve more of the things that matter to us the most. Fear is not a powerful motivator for learning. But when we are truly excited about something, we will be relentless in developing the skills and capabilities we need to succeed.

The key to discovering our own passion of the explorer is to pay attention to our emotions and the emotions of those we admire. We need to be relentless in our search for experiences that excite and inspire us, and we must not rest until we find the domain that generates the most excitement in us. We’ll discuss this in more detail in the next chapter.

NARRATIVES AS CATALYSTS FOR THE PASSION OF THE EXPLORER

Narratives can be powerful tools for unleashing the passion of the explorer within us. The right narrative at the right time can create the conditions that catalyze and draw out the three attributes that define the passion of the explorer.

The right narrative draws out the first attribute—a long-term commitment to a domain—by helping us define domains and hear a call to action. Narratives are typically about a broad domain, rather than a narrow slice of experience, and tell about a big opportunity or threat somewhere in the future. Think about famous movement narratives like the ones that arise out of religions, national narratives like “the American dream,” and regional narratives like Silicon Valley’s. Consider institutional narratives like Apple’s narrative about the opportunity to unleash our unique identity by harnessing new generations of technology and Nike’s narrative about the opportunity to achieve exciting new levels of physical performance by moving from being passive observers to active participants in sports.

Besides mapping out a broad domain, a narrative calls us to make choices and take action, thereby moving us beyond simple curiosity to an active commitment to making a difference. An opportunity-based narrative identifies a wonderful opportunity within the domain that is available to all of us if we choose to pursue it. A narrative can provide a valuable focus for our efforts as we begin to explore a new domain. But ultimately, it’s up to us. Will we make that commitment? Will we take the actions required to participate in that opportunity?

Opportunity-based narratives are not just about opportunities; they also frame the challenges we’ll encounter along the way. To participate in the long-term opportunity, you need to take on and overcome the challenges that await you. That dual focus on opportunity and challenges helps to draw out the second attribute of the passion of the explorer, a questing disposition. Rather than trying to avoid challenges when they occur, narratives encourage us to seek them out.

Finally, to draw out the third attribute of the passion of the explorer, a connecting disposition, narratives assure us that the opportunity ahead is not just for one lucky winner. It’s available to many, if not all, of us. These are not zero-sum opportunities. We can all participate and win. That message encourages us to come together to help each other over the finish line. The more people who share our excitement, the more excited we become.

As more and more people acquire the passion of the explorer, they accomplish awesome things. The stories of their amazing accomplishments begin to spread, giving additional credibility to the broader narrative. Look at what others have accomplished; you can do the same or even better. Will you join us? Will you make the choices and take the actions required to pursue this exciting opportunity? The narrative is enriched by the experiences of others. It spreads as more and more people see the tangible evidence of what can be accomplished.

Not all of us will be drawn equally to any one narrative. But narratives can become bright beacons that cause us to reflect on the purpose and direction of our lives. They are powerful antidotes to the institutions and practices that discourage and ultimately quash passion in their quest for predictability and standardization. They call us to reconnect with the passion we felt as children and to move from the passion of the player, which most of us had as kids, to the passion of the explorer, motivating us to make a long-term commitment to a specific domain.

If opportunity-based narratives can become a catalyst for drawing out the passion of the explorer, threat-based ones can do the opposite. You know the kind I’m talking about; we’re increasingly surrounded by them. These focus on an imminent danger: we’re under attack, and if we don’t band together now, all the things we hold precious are going to disappear, and we’ll probably die. Threat-based narratives are often deeply conservative or even reactionary. They want to preserve what we have, rather than explore what we could become. This tends to ignite a different form of passion—the passion of the true believer. In this kind of passion, the destination is clear, and the path we need to take to reach that destination is tightly mapped out. Threat-based narratives and the passion of the true believer have combined throughout history to create many of the social movements that have wreaked havoc in our world. Nevertheless, even here, the tight connection of narrative and passion helps to explain the power of these movements.

BOTTOM LINE

Passion can take many different forms. We can gain insight from stepping back and reflecting on whether we have developed any passions and, if so, what kind of passions we are pursuing.

We all need to find and cultivate the passion of the explorer. It provides the fuel that will sustain us on our journey toward whatever we are pursuing. Most importantly, it will help us overcome our fear and replace it with hope and excitement as we begin to address the expanding opportunities ahead. This is an imperative for all of us. We need to discover and cultivate the passion of the explorer that is within us all.

Narratives can be a significant catalyst in drawing out this passion of the explorer, helping to create a world in which pressure evolves from a source of fear to a source of excitement, calling us to achieve even more of our potential, both as individuals and collectively. By drawing out the passion that lies dormant within us, narratives can help us accomplish the seemingly impossible.

Some of us found the passion of the explorer early in our lives. Many of us are still searching for it, often unconsciously. If you are searching, certain steps ensure you will find it. I will tell you about those steps in the chapters to come. In the meantime, here are some questions for reflection:

• Do you know anyone who has the passion of the explorer?

• Have you developed a passion of the explorer?

• If so, how might you connect with more people who share it?

• If not, are you actively searching to find a passion that engages you?

• If not, what has held you back?