Identifying the Minimum Acceptable Level of Risk and Appropriate Security Baseline Definitions

For an organization to develop security baselines, it must select proper controls. However, the decision to apply or not apply controls is based on risk. Specifically, the controls put in place manage the identified risks. As a result, a risk assessment needs to be completed first.

It might seem easiest to apply a wide range of controls based on different recommendations. Remember, however, that there are costs associated with these controls. For example, you can take many different steps to secure your home and minimize risks. Most people consider door locks as necessary. Beyond that, there is no universal rule of home security to which everyone adheres. Even door locks are available in varying strengths. Consider other measures a homeowner might take. Examples include bars on the windows, storm shutters, insurance, burglar alarms, smoke detectors, carbon monoxide detectors, cameras, safes, watchdogs, outdoor lighting, fences, and even weapons. These examples of home controls are similar to IT controls in that there is a cost associated with each of them. Depending on the type or mission of the business, the cost justifications vary. The controls are based on the level of risk the organization faces.

Security controls follow three unique design types:

-

Preventive

-

Detective

-

Corrective

Preventive Security Control

A preventive control, also sometimes called “preventative control,” stops incidents or breaches immediately. As the name implies, it’s designed to prevent an incident from occurring. A firewall ideally would stop a hacker from getting inside the organization’s network. This kind of control is an automated control.

Automated control has logic in software to decide what action to take. With an automated control, no human decisions are needed to prevent an incident from occurring. The human decisions occurred when the security control was designed.

Detective Security Control

A detective control does not prevent incidents or breaches immediately. Just as a burglar alarm might call the police, a security control alerts an organization that an incident might have occurred. When you review a credit card statement, your review is a detective control. You review the statement for unauthorized charges. The process of reviewing the statement did not prevent the unauthorized charge from occurring. The review, however, triggers corrective action if needed.

A detective control is considered a manual control. A manual control relies on a human to decide what action to take. Still, manual controls can have automated components. For example, a system administrator could automatically receive a cell phone text when the number of invalid login attempts reaches some threshold on a server. The administrator still needs to take some manual action.

Corrective Security Control

A corrective control does not prevent incidents or breaches immediately. A corrective security control limits the impact on the business by correcting the vulnerability. How quickly the business can restore its operations determines the effectiveness of the control.

For example, backing up files to be able to restore data after a system crash is a corrective security control. A corrective control is either automated or manual. For instance, you may automatically mirror (create exact copies of) files and then restore them in the event of hard drive failure. This is an automated control. If a human is required to decide when to restore the backup, that is a manual control.

Remember that IT is not completely independent. IT exists to support the business. Understanding the minimum level of acceptable risk and implementing baseline controls depend on IT being aligned with the objectives of the business.

Organization-Wide

Establishing a baseline based on a control framework needs to be relative to the risk appetite of the organization. The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) defines risk appetite as “the degree of risk, on a broad based level, that an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of value.” Management considers the organization’s risk appetite first in evaluating strategic alternatives, then in setting objectives aligned with the selected strategy, and in developing mechanisms to manage the related risks. Risk appetite is a broad-based look at the amount of risk an organization is willing to take to achieve its objectives. This should not be confused with risk tolerance. Risk tolerance is about the ranges of acceptance for specific risks. Identifying levels of risk tolerance allows the organization to stay within its defined appetite for risk.

IT supports the enterprise risk management (ERM) strategy in a few ways:

-

ERM depends on accurate and timely information. Information systems process and store this information. Maintaining the integrity and availability of the data is needed. As a result, adequate controls need to be placed on systems.

-

The IT environment supports not only the ERM function but also all other operations of the business. As a result, the IT environment and associated controls need to be aligned with the organization.

In addition to looking at individual controls, an auditor will ensure the IT environment is aligned with the organization’s risk appetite. Additionally, the auditor will assess the organizational alignment among the various risk functions, which is sometimes referred to as the three lines of defense.

The first line of defense is the business unit (BU). The business deals with controlling risk on day-to-day business. It identifies risk within the business, assesses the impact, and mitigates the risk whenever possible. The business is expected to follow policies and implement the ERM program. The business will develop both short- and long-term strategies for reducing its risk within the BU. The BU would own the risk. Meaning, they are directly accountable to ensure the risk is mitigated or reduced.

The second line of defense is the ERM program. This team is responsible for managing risk at an enterprise level. The team provides guidance and advice to the first line. They align policies and ensure the risk management program aligns with company goals. The team has oversight and management roles of risk committees and risk initiatives.

The second line is responsible for engaging the business to develop a risk strategy and gauging the risk appetite of the organization. They have an obligation to report to the board material noncompliance and excessive risks that put the organization's goal at jeopardy.

The third line of defense is the independent auditor. The auditor’s role is to provide the board and executive management independent assurance that the controls and risk function is designed and working well. Additionally, auditors serve as advisors to the first and second lines of defense in risk matters. The third line must keep its independence but does have an important role to provide input on risk strategies and directions.

There are several views on how closely involved the third line of defense can be in advising leadership without losing its independence. Their concern is if the third line of defense advises on a course of action, can they now audit and develop a truly independent opinion on its success? Many audit organizations develop rules of engagement to avoid conflict. There are also several views on whether their external auditors are the fourth line of defense or part of the third line.

This model demonstrates how organizational roles can be used to create a separation of duties within the risk functions. In the ideal world, the first line of defense would self-assess and identify all the risks. It’s not realistic to expect such precision. What is not caught in the first line, the second line should catch. What the first and second lines do not catch, the third line should catch. At this point, while risks still exist in the environment, these risks should not be significant and should be manageable. Consequently, a regulator determination that an organization is not in compliance with regulation would also lead to questions about the effectiveness of the organization’s three lines of defense.

Seven Domains of a Typical IT Infrastructure

After considering the organization’s risk appetite and tolerance, further consideration of the following is needed:

-

The value and importance of data

-

Risks to the IT infrastructure

-

The level of expected quality of service

The seven domains of a typical IT infrastructure are composed of people, processes, and technology. This includes employees, partners, and customers interacting with data and using software and applications across a hardware infrastructure. Looking across the seven domains of a typical IT infrastructure can reveal immediate vulnerabilities. For example, domains consisting of remote access, wide-area networks (WANs), and cloud computing environments all reveal potential rogue Internet connectivity. Gathering the appropriate documents can provide an immediate view into the domains and inventory of the IT infrastructure.

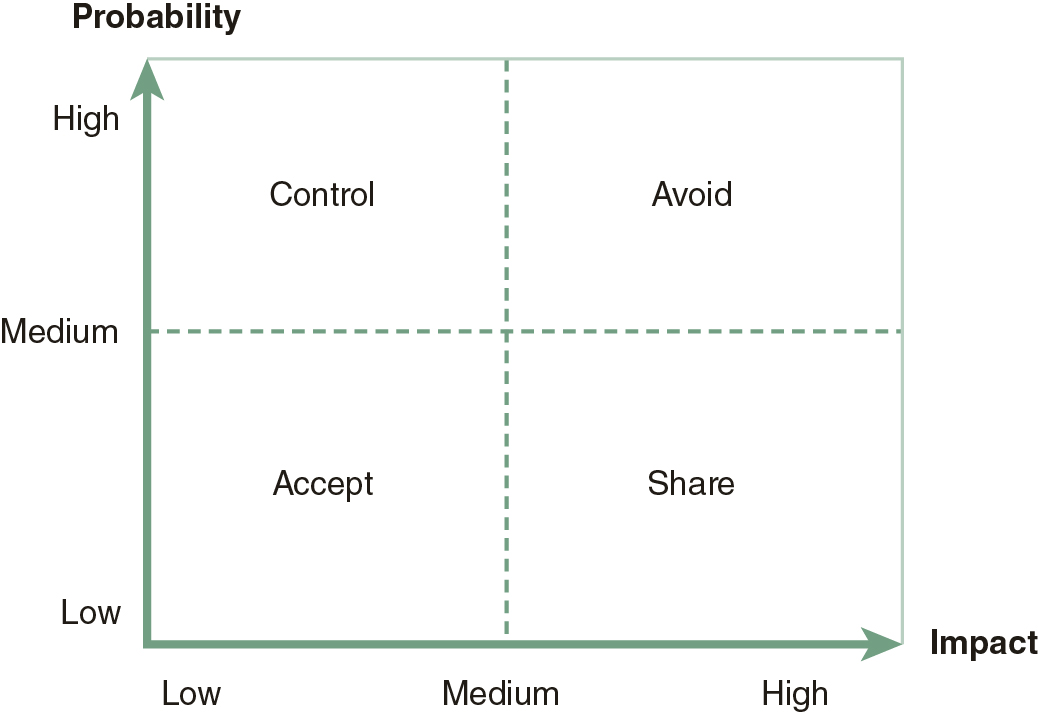

Mitigating risk within the IT infrastructure includes the application of controls. Again, the risks that organizations want to minimize are based on the value of the assets coupled with how a vulnerability being exploited by a threat would affect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the data and associated systems. Reducing the risk depends on what controls are available, how much they cost, and if they are cost efficient. As a result of this analysis, organizations typically take a risk-based approach. A more detailed look at these strategies includes the following:

-

Accept the risk—Do nothing and manage the consequences if the risk is realized.

-

Avoid the risk—Seek alternatives or don’t participate in the risky activity.

-

Share the risk—Transfer or divide the risk with other parties.

-

Control the risk—Apply mechanisms or countermeasures to minimize the effects of the risk.

Figure 6-1 provides a simple illustration of components of risk and how the preceding strategies might be applied. The approach an organization takes needs to consider the risk appetite of the organization. The risk might be so great, for example, that avoidance might be the best solution.

FIGURE 6-1 Applying Risk-Management Strategies

Business Liability Insurance

Business liability insurance is a way of sharing the risk as it lowers the financial loss to the business in the event of an incident. Even when a business has well-defined security policies, problems can still occur. Business liability insurance will pay the business for losses within the limits of the policy.

Business liability insurance can be issued to both organizations and individuals. For example, a computer engineer performing consulting services could obtain professional liability insurance. Such a policy would cover any successful claims that they were negligent or made errors during the performance of their professional services. The same type of coverage would apply to large companies facing claims that their product or services were negligent or in error.

An important benefit of this insurance coverage is the payment of legal fees. Even when found innocent, the legal costs can be substantial. These policies do have set limits, conditions, and requirements that the policyholder must meet. These policies also have exclusions such as illegal acts that void the policy. Overall these insurance policies are another good tool to further reduce the risk beyond the effort taken by the company to manage business risk.

Controlling Risk

Compensating controls are alternative measures put in place to mitigate a risk in lieu of implementing a control requirement or best practice. Suppose you don’t want to spend the money on anti-virus software and choose to accept the risks. You might take a compensating measure, such as not opening file attachments or only visiting reputable websites. Often, layering compensating controls is necessary. In addition to changing your habits, you might also back up your data regularly.

Armed with an understanding of risks within the IT infrastructure, the risk-mitigation strategies will be factored into the appropriate security baseline. An audit of the baseline controls will determine the following:

-

Are the controls effective at reducing the targeted risk?

-

Do the controls incorporate a mix of preventive, detective, and corrective controls?

-

How are the controls monitored and audited in case of failure or breach?

The term baseline control comes from the configuration management function. Configuration management describes activities that lead and standardize configurations. A configuration represents controls applied to any IT infrastructure device or software. According to the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), a baseline, also called a reference configuration, is: “A specification or product that has been formally reviewed and agreed to by responsible management, that thereafter serves as the basis for further development, and can be changed only through formal change control procedures.”

For example, a firewall baseline may determine which ports should or should not be open depending on the business need. Baselines are product-specific. For example, a baseline for Microsoft SQL database versus Oracle database may both disable the default account but will achieve that requirement using different product settings.

Baselines are important because they simplify the audit process. An auditor would first verify the baseline is compliant with policy and industry norms. Once the baseline is verified, the auditor would then verify the baseline has been applied consistently across the IT infrastructure. For example, let’s assume an organization hosts 200 database servers of the same type. Potentially an auditor needs only to check the baseline configuration to meet policy requirements once. Then test if the same configuration was applied to the 200 servers. Any unauthorized deviation from the baseline would be considered noncompliance.

Gap Analysis for the Seven Domains

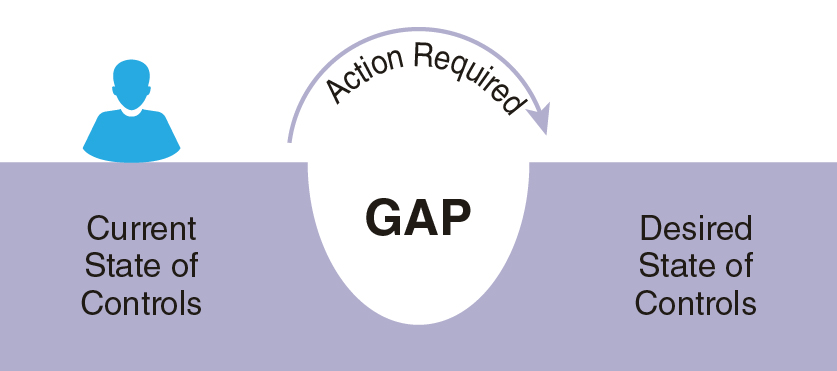

A gap analysis is an examination of the current state of controls against the desired state of controls, as illustrated in Figure 6-2. The difference between the two indicates the required action. The ongoing risk-assessment process determines the desired state. Thus, once a gap is closed, it does not necessarily stay that way. The results of a gap analysis determine the absence of baseline controls. Moreover, a gap analysis is ideally used once a baseline is established. It further defines the need for additional controls or enhancements to existing controls.

FIGURE 6-2 Control Gap Analysis

Analyzing gaps requires attention to the type of system and its value or criticality. Depending on the criticality of the system, different baselines may apply. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides baseline control recommendations across three different types of information systems: low impact, moderate impact, and high impact. NIST provides different baseline controls for different classifications. For example, users accessing low-impact systems might be required to identify themselves with a unique user name and authenticate with a password. This would meet a baseline requirement of an information system uniquely identifying and authenticating users.

Consider an example from NIST 800-53 for monitoring physical access in an information system environment. The control states that the organization should do the following:

-

Monitor physical access to the facility where the information system resides to detect and respond to physical security incidents.

-

Review physical access logs.

-

Coordinate results of reviews and investigations with the organization’s incident response capability.

The previous points represent the baseline control for all systems regardless of the impact level. NIST further provides two more control enhancements for monitoring physical access. These are as follows:

-

The organization monitors physical intrusion alarms and surveillance equipment.

-

The organization employs automated mechanisms to recognize potential intrusions and initiate designated response actions.

Systems designated as moderate impact would require not only the original baseline control but also the first control from the previous two items. The high-impact system baseline control would require the original baseline control and both controls from the previous list. If an organization had broadly implemented the original baseline controls but not the others, a gap analysis would reveal whether the control enhancements were necessary. As a result, the organization would clearly understand where it currently stands with regard to monitoring physical access. It would also understand where it needs to be and have clear guidance on what it needs to do to fill the gap.