Logistics, the supply chain and competitive strategy

- Supply chain management is a wider concept than logistics

- Competitive advantage

- The supply chain becomes the value chain

- The mission of logistics management

- The supply chain and competitive performance

- The changing competitive environment

Logistics and supply chain management are not new ideas. From the building of the pyramids to the relief of hunger in Africa there has been little change to the principles underpinning the effective flow of materials and information to meet the requirements of customers.

Throughout the history of mankind, wars have been won and lost through logistics‘ strengths and capabilities – or the lack of them. It has been argued that the defeat of the British in the American War of Independence can largely be attributed to logistics failures. The British Army in America depended almost entirely upon Britain for supplies; at the height of the war there were 12,000 troops overseas and for the most part they had not only to be equipped, but fed from Britain. For the first six years of the war the administration of these vital supplies was totally inadequate, affecting the course of operations and the morale of the troops. An organisation capable of supplying the army was not developed until 1781 and by then it was too late.1

In the Second World War logistics also played a major role. The Allied Forces’ invasion of Europe was a highly skilled exercise in logistics, as was the defeat of Rommel in the desert. Rommel himself once said that ‘… before the fighting proper, the battle is won or lost by quartermasters’.

However, whilst the Generals and Field Marshals from the earliest times have understood the critical role of logistics, strangely it is only in the recent past that business organisations have come to recognise the vital impact that logistics management can have in the achievement of competitive advantage. Partly this lack of recognition springs from the relatively low level of understanding of the benefits of integrated logistics. As early as 1915, Arch Shaw2 pointed out that:

The relations between the activities of demand creation and physical supply … illustrate the existence of the two principles of interdependence and balance. Failure to co-ordinate any one of these activities with its group-fellows and also with those in the other group, or undue emphasis or outlay put upon any one of these activities, is certain to upset the equilibrium of forces which means efficient distribution.

… The physical distribution of the goods is a problem distinct from the creation of demand … Not a few worthy failures in distribution campaigns have been due to such a lack of co-ordination between demand creation and physical supply …

Instead of being a subsequent problem, this question of supply must be met and answered before the work of distribution begins.

It is paradoxical that it has taken 100 years for these basic principles of logistics management to be widely accepted.

What is logistics management in the sense that it is understood today? There are many ways of defining logistics, but the underlying concept might be defined as follows:

Logistics is the process of strategically managing the procurement, movement and storage of materials, parts and finished inventory (and the related information flows) through the organisation and its marketing channels in such a way that current and future profitability are maximised through the cost-effective fulfilment of orders.

Ultimately, the mission of logistics management is to serve customers in the most cost-effective way. A recurring theme throughout this book is that the way we reach and serve customers has become a critical competitive dimension. Hence the need to look at logistics in a wider business context and to see it as far more than a set of tools and techniques

Supply chain management is a wider concept than logistics

Logistics is essentially a planning orientation and framework that seeks to create a single plan for the flow of products and information through a business. Supply chain management builds upon this framework and seeks to achieve linkage and co-ordination between the processes of other entities in the pipeline, i.e. suppliers and customers, and the organisation itself. Thus, for example, one goal of supply chain management might be to reduce or eliminate the buffers of inventory that exist between organisations in a chain through the sharing of information regarding demand and current stock levels.

The concept of supply chain management is relatively new. It was first articulated in a white paper3 produced by a consultancy firm – then called Booz, Allen and Hamilton – back in 1982. The authors, Keith Oliver and Michael Webber, wrote:

Through our study of firms in a variety of industries … we found that the traditional approach of seeking trade-offs among the various conflicting objective of key functions – purchasing, production, distribution and sales – along the supply chain no longer worked very well. We needed a new perspective and, following from it, a new approach: Supply-chain management.

It will be apparent that supply chain management involves a significant change from the traditional arm’s-length, even adversarial, relationships that have so often typified buyer/supplier relationships in the past and still today. The focus of supply chain management is on co-operation and trust and the recognition that, properly managed, the ‘whole can be greater than the sum of its parts’.

The definition of supply chain management that is adopted in this book is:

The management of upstream and downstream relationships with suppliers and customers in order to deliver superior customer value at less cost to the supply chain as a whole.

Thus the focus of supply chain management is upon the management of relationships in order to achieve a more profitable outcome for all parties in the chain. This brings with it some significant challenges as there may be occasions when the narrow self interest of one party has to be subsumed for the benefit of the chain as a whole.

Whilst the phrase ‘supply chain management’ is now widely used, it could be argued that ‘demand chain management’ would be more appropriate, to reflect the fact that the chain should be driven by the market, not by suppliers. Equally, the word ‘chain’ should be replaced by ‘network’ as there will normally be multiple suppliers and, indeed, suppliers to suppliers as well as multiple customers and customers’ customers to be included in the total system.

Figure 1.1 illustrates this idea of the firm being at the centre of a network of suppliers and customers.

Extending this idea, it has been suggested that a supply chain could more accurately be defined as:

A network of connected and interdependent organisations mutually and co-operatively working together to control, manage and improve the flow of materials and information from suppliers to end users.4

Competitive advantage

A central theme of this book is that effective logistics and supply chain management can provide a major source of competitive advantage – in other words, a position of enduring superiority over competitors in terms of customer preference may be achieved through better management of logistics and the supply chain.

The foundations for success in the marketplace are numerous, but a simple model is based around the triangular linkage of the company, its customers and its competitors – the ‘Three Cs’. Figure 1.2 illustrates the three-way relationship.

Figure 1.2 Competitive advantage and the ‘Three Cs’

Source: Ohmae, K., The Mind of the Strategist, Penguin Books, 1983

The source of competitive advantage is found firstly in the ability of the organisation to differentiate itself positively, in the eyes of the customer, from its competition, and secondly by operating at a lower cost and hence at greater profit.

Seeking a sustainable and defensible competitive advantage has become the concern of every manager who is alert to the realities of the marketplace. It is no longer acceptable to assume that good products will sell themselves, neither is it advisable to imagine that success today will carry forward into tomorrow.

Let us consider the bases of success in any competitive context. At its most elemental, commercial success derives from either a cost advantage or a value advantage or, ideally, both. It is as simple as that – the most profitable competitor in any industry sector tends to be the lowest-cost producer or the supplier providing a product with the greatest perceived differentiated values.

Put very simply, successful companies either have a cost advantage or they have a value advantage, or – even better – a combination of the two. Cost advantage gives a lower cost profile and the value advantage gives the product or offering a differential ‘plus’ over competitive offerings.

Let us briefly examine these two vectors of strategic direction.

1 Cost advantage

In many industries there will typically be one competitor who will be the low-cost producer and often that competitor will have the greatest sales volume in the sector. There is substantial evidence to suggest that ‘big is beautiful’ when it comes to cost advantage. This is partly due to economies of scale, which enable fixed costs to be spread over a greater volume, but more particularly to the impact of the ‘experience curve’.

The experience curve is a phenomenon with its roots in the earlier notion of the ‘learning curve’. Researchers in the Second World War discovered that it was possible to identify and predict improvements in the rate of output of workers as they became more skilled in the processes and tasks on which they were working. Subsequent work by Boston Consulting Group extended this concept by demonstrating that all costs, not just production costs, would decline at a given rate as volume increased (see Figure 1.3). In fact, to be precise, the relationship that the experience curve describes is between real unit costs and cumulative volume.

Figure 1.3 The experience curve

Traditionally, it has been suggested that the main route to cost reduction was through the achievement of greater sales volume and in particular by improving market share. However, the blind pursuit of economies of scale through volume increases may not always lead to improved profitability – in today’s world much of the cost of a product lies outside the four walls of the business in the wider supply chain. Hence it can be argued that it is increasingly through better logistics and supply chain management that efficiency and productivity can be achieved, leading to significantly reduced unit costs. How this can be achieved will be one of the main themes of this book.

2 Value advantage

It has long been an axiom in marketing that ‘customers don’t buy products, they buy benefits’. Put another way, the product is purchased not for itself but for the promise of what it will ‘deliver’. These benefits may be intangible, i.e. they relate not to specific product features but rather to such things as image or service. In addition, the delivered offering may be seen to outperform its rivals in some functional aspect.

Unless the product or service we offer can be distinguished in some way from its competitors, there is a strong likelihood that the marketplace will view it as a ‘commodity’ and so the sale will tend to go to the cheapest supplier. Hence the importance of seeking to add additional values to our offering to mark it out from the competition.

What are the means by which such value differentiations may be gained? Essentially, the development of a strategy based upon added values will normally require a more segmented approach to the market. When a company scrutinises markets closely, it frequently finds that there are distinct ‘value segments’. In other words, different groups of customers within the total market attach different importance to different benefits. The importance of such benefit segmentation lies in the fact that often there are substantial opportunities for creating differentiated appeals for specific segments. Take the car industry as an example. Most volume car manufacturers such as Toyota or Ford offer a range of models positioned at different price points in the market. However, it is increasingly the case that each model is offered in a variety of versions. Thus at one end of the spectrum may be the basic version with a small engine and three doors, and at the other end a five-door, high-performance version. In between are a whole variety of options, each of which seeks to satisfy the needs of quite different ‘benefit segments’. Adding value through differentiation is a powerful means of achieving a defensible advantage in the market.

Equally powerful as a means of adding value is service. Increasingly it is the case that markets are becoming more service-sensitive and this of course poses particular challenges for logistics management. There is a trend in many markets towards a decline in the strength of the ‘brand’ and a consequent move towards ‘commodity’ market status. Quite simply, this means that it is becoming progressively more difficult to compete purely on the basis of brand or corporate image. Additionally, there is increasingly a convergence of technology within product categories, which means that it is often no longer possible to compete effectively on the basis of product differences. Thus the need to seek differentiation through means other than technology. Many companies have responded to this by focusing upon service as a way of gaining a competitive edge. In this context service relates to the process of developing relationships with customers through the provision of an augmented offer. This augmentation can take many forms, including delivery service, after-sales services, financial packages, technical support and so forth.

Seeking the high ground

In practice what we find is that the successful companies will often seek to achieve a position based upon both a cost advantage and a value advantage. A useful way of examining the available options is to present them as a simple matrix (Figure 1.4). Let us consider these options in turn.

Figure 1.4 Logistics and competitive advantage

For companies who find themselves in the bottom left-hand corner of our matrix, the world is an uncomfortable place. Their products are indistinguishable from their competitors’ offerings and they have no cost advantage. These are typical commodity market situations and ultimately the only strategy is either to move to the right of the matrix, i.e. to cost leadership, or upwards towards service leadership. Often the cost leadership route is simply not available. This particularly will be the case in a mature market where substantial market share gains are difficult to achieve. New technology may sometimes provide a window of opportunity for cost reduction, but in such situations the same technology is often available to competitors.

Cost leadership strategies have traditionally been based upon the economies of scale, gained through sales volume. This is why market share is considered to be so important in many industries. However, if volume is to be the basis for cost leadership then it is preferable for that volume to be gained early in the market life cycle. The ‘experience curve’ concept, briefly described earlier, demonstrates the value of early market share gains – the higher your share relative to your competitors the lower your costs should be. This cost advantage can be used strategically to assume a position of price leader and, if appropriate, to make it impossible for higher-cost competitors to survive. Alternatively, price may be maintained, enabling above-average profit to be earned, which potentially is available to further develop the position of the product in the market.

However, an increasingly powerful route to achieving a cost advantage comes not necessarily through volume and the economies of scale but instead through logistics and supply chain management. In many industries, logistics costs represent such a significant proportion of total costs that it is possible to make major cost reductions through fundamentally re-engineering logistics processes. The means whereby this can be achieved will be returned to later in this book.

The other way out of the ‘commodity’ quadrant of the matrix is to seek a strategy of differentiation through service excellence. We have already commented on the fact that markets have become more ‘service-sensitive’. Customers in all industries are seeking greater responsiveness and reliability from suppliers: they are looking for reduced lead-times, just-in-time (JIT) delivery and value-added services that enable them to do a better job of serving their customers. In Chapter 2 we will examine the specific ways in which superior service strategies, based upon enhanced logistics management, can be developed.

Figure 1.5 The challenge to logistics and supply chain management

One thing is certain: there is no middle ground between cost leadership and service excellence. Indeed, the challenge to management is to identify appropriate logistics and supply chain strategies to take the organisation to the top right-hand corner of the matrix. Companies which occupy that position have offers that are distinctive in the value they deliver and are also cost competitive. Clearly it is a position of some strength, occupying ‘high ground’ that is extremely difficult for competitors to attack. Figure 1.5 presents the challenge: to seek out strategies that will take the business away from the ‘commodity’ end of the market towards a more secure position of strength based upon differentiation and cost advantage.

Logistics and supply chain management, it can be argued, has the potential to assist the organisation in the achievement of both a cost advantage and a value advantage. As Figure 1.6 suggests, in the first instance there are a number of important ways in which productivity can be enhanced through logistics and supply chain management. Whilst these possibilities for leverage will be discussed in detail later in the book, suffice it to say that the opportunities for better capacity utilisation, inventory reduction and closer integration with suppliers at a planning level are considerable. Equally the prospects for gaining a value advantage in the marketplace through superior customer service should not be under-estimated. It will be argued later that the way we service the customer has become a vital means of differentiation.

Figure 1.6 Gaining competitive advantage

To summarise, those organisations that will be the leaders in the markets of the future will be those that have sought and achieved the twin peaks of excellence: they have gained both cost leadership and service leadership.

The underlying philosophy behind the logistics and supply chain concept is that of planning and co-ordinating the materials flow from source to user as an integrated system rather than, as was so often the case in the past, managing the goods flow as a series of independent activities. Thus, under this approach the goal is to link the marketplace, the distribution network, the manufacturing process and the procurement activity in such a way that customers are serviced at higher levels and yet at lower cost. In other words, the goal is to achieve competitive advantage through both cost reduction and service enhancement.

The supply chain becomes the value chain

Of the many changes that have taken place in management thinking over the last 30 years or so, perhaps the most significant has been the emphasis placed upon the search for strategies that will provide superior value in the eyes of the customer. To a large extent the credit for this must go to Michael Porter, the Harvard Business School professor who, through his research and writing, has alerted managers and strategists to the central importance of competitive relativities in achieving success in the marketplace.

One concept in particular that Michael Porter has brought to a wider audience is the ‘value chain’5:

Competitive advantage cannot be understood by looking at a firm as a whole. It stems from the many discrete activities a firm performs in designing, producing, marketing, delivering, and supporting its product. Each of these activities can contribute to a firm’s relative cost position and create a basis for differentiation … The value chain disaggregates a firm into its strategically relevant activities in order to understand the behaviour of costs and the existing and potential sources of differentiation. A firm gains competitive advantage by performing these strategically important activities more cheaply or better than its competitors.

Value chain activities (shown in Figure 1.7) can be categorised into two types – primary activities (in-bound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service) and support activities (infrastructure, human resource management, technology development and procurement). These activities are integrating functions that cut across the traditional functions of the firm. Competitive advantage is derived from the way in which firms organise and perform these activities within the value chain. To gain competitive advantage over its rivals, a firm must deliver value to its customers by performing these activities more efficiently than its competitors or by performing the activities in a unique way that creates greater differentiation.

The implication of Michael Porter’s thesis is that organisations should look at each activity in their value chain and assess whether they have a real competitive advantage in the activity. If they do not, the argument goes, then perhaps they should consider outsourcing that activity to a partner who can provide that cost or value advantage. This logic is now widely accepted and has led to the dramatic upsurge in outsourcing activity that can be witnessed in almost every industry.

Whilst there is often a strong economic logic underpinning the decision to outsource activities that may previously have been performed in-house, such decisions may add to the complexity of the supply chain. Because there are, by definition, more interfaces to be managed as a result of outsourcing, the need for a much higher level of relationship management increases.

Source: Reprinted with the permission of The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. from Competitive Advantage by Porter, M. E. Copyright © 1985 by Porter, M. E. All rights reserved

The effect of outsourcing is to extend the value chain beyond the boundaries of the business. In other words, the supply chain becomes the value chain. Value (and cost) is not just created by the focal firm in a network, but by all the entities that connect to each other. This ‘extended enterprise’, as some have termed it, becomes the vehicle through which competitive advantage is gained – or lost.

The mission of logistics management

It will be apparent from the previous comments that the mission of logistics management is to plan and co-ordinate all those activities necessary to achieve desired levels of delivered service and quality at the lowest possible cost. Logistics must therefore be seen as the link between the marketplace and the supply base. The scope of logistics spans the organisation, from the management of raw materials through to the delivery of the final product. Figure 1.8 illustrates this total systems concept.

Logistics management, from this total systems viewpoint, is the means whereby the needs of customers are satisfied through the co-ordination of the materials and information flows that extend from the marketplace, through the firm and its operations and beyond that to suppliers. To achieve this company-wide integration requires a quite different orientation than typically encountered in the conventional organisation.

For example, for many years marketing and manufacturing have been seen as largely separate activities within the organisation. At best they have co-existed, at worst there has been open warfare. Manufacturing priorities and objectives have typically been focused on operating efficiency, achieved through long production runs, minimised set-ups and change-overs and product standardisation. Conversely, marketing has sought to achieve competitive advantage through variety, high service levels and frequent product changes.

In today’s more turbulent environment there is no longer any possibility of manufacturing and marketing acting independently of each other. The internecine disputes between the ‘barons’ of production and marketing are clearly counter-productive to the achievement of overall corporate goals.

It is no coincidence that in recent years both marketing and manufacturing have become the focus of renewed attention. Marketing as a concept and a philosophy of customer orientation now enjoys a wider acceptance than ever. It is now generally accepted that the need to understand and meet customer requirements is a prerequisite for survival. At the same time, in the search for improved cost competitiveness, manufacturing management has been the subject of a massive revolution. The last few decades have seen the introduction of flexible manufacturing systems (FMS), of new approaches to inventory based on materials requirements planning (MRP) and JIT methods and, perhaps most important of all, a sustained emphasis on total quality management (TQM).

Equally there has been a growing recognition of the critical role that procurement plays in creating and sustaining competitive advantage as part of an integrated logistics process. Leading-edge organisations now routinely include supply-side issues in the development of their strategic plans. Not only is the cost of purchased materials and supplies a significant part of total costs in most organisations, but there is a major opportunity for leveraging the capabilities and competencies of suppliers through closer integration of the buyers’ and suppliers’ logistics processes.

In this scheme of things, logistics is therefore essentially an integrative concept that seeks to develop a system-wide view of the firm. It is fundamentally a planning concept that seeks to create a framework through which the needs of the marketplace can be translated into a manufacturing strategy and plan, which in turn links into a strategy and plan for procurement. Ideally there should be a ‘one-plan’ mentality within the business that seeks to replace the conventional stand-alone and separate plans for marketing, distribution, production and procurement. This, quite simply, is the mission of logistics management.

The supply chain and competitive performance

Traditionally most organisations have viewed themselves as entities that not only exist independently from others but need to compete with them in order to survive. However, such a philosophy can be self-defeating if it leads to an unwillingness to co-operate in order to compete. Behind this seemingly paradoxical concept is the idea of supply chain integration.

The supply chain is the network of organisations that are involved, through upstream and downstream linkages, in the different processes and activities that produce value in the form of products and services in the hands of the ultimate consumer. Thus, for example, a shirt manufacturer is a part of a supply chain that extends upstream through the weavers of fabrics to the manufacturers of fibres, and downstream through distributors and retailers to the final consumer. Each of these organisations in the chain are dependent upon each other by definition and yet, paradoxically, by tradition do not closely co-operate with each other.

Supply chain management is not the same as ‘vertical integration’. Vertical integration normally implies ownership of upstream suppliers and downstream customers. This was once thought to be a desirable strategy but increasingly organisations are now focusing on their ‘core business’ – in other words the things they do really well and where they have a differential advantage. Everything else is ‘outsourced’ – procured outside the firm. So, for example, companies that perhaps once made their own components now only assemble the finished product, e.g. automobile manufacturers. Other companies may subcontract the manufacturing as well, e.g. Nike in footwear and sportswear. These companies have sometimes been termed ‘virtual’ or ‘network’ organisations.

GANT: Creating value across a virtual network

A good example of a virtual organisation is the Swedish clothing brand GANT. At the centre of the network is Pyramid Sportswear AB, which directly employs fewer than ten people. Pyramid contracts with designers, identifies trends, uses contract manufacturers, develops the retailer network and creates the brand image through marketing communications. Through its databases, Pyramid closely monitors sales, inventories and trends. Its network of closely co-ordinated partners means it can react quickly to changes in the market. The network itself changes as requirements change, and it will use different designers, freelance photographers, catalogue producers, contract manufacturers and so on as appropriate.

SOURCE: CHRISTOPHER, M., PAYNE, A. & BALLANTYNE, D., RELATIONSHIP MARKETING: CREATING STAKEHOLDER VALUE, BUTTERWORTH HEINNEMANN, OXFORD 2002

Clearly this trend has many implications for supply chain management, not the least being the challenge of integrating and co-ordinating the flow of materials from a multitude of suppliers, often offshore, and similarly managing the distribution of the finished product by way of multiple intermediaries.

In the past it was often the case that relationships with suppliers and downstream customers (such as distributors or retailers) were adversarial rather than co-operative. It is still the case today that some companies will seek to achieve cost reductions or profit improvement at the expense of their supply chain partners. Companies such as these do not realise that simply transferring costs upstream or downstream does not make them any more competitive. The reason for this is that ultimately all costs will make their way to the final marketplace to be reflected in the price paid by the end user. The leading-edge companies recognise the fallacy of this conventional approach and instead seek to make the supply chain as a whole more competitive through the value it adds and the costs that it reduces overall. They have realised that the real competition is not company against company but rather supply chain against supply chain.

It must be recognised that the concept of supply chain management, whilst relatively new, is in fact no more than an extension of the logic of logistics. Logistics management is primarily concerned with optimising flows within the organisation, whilst supply chain management recognises that internal integration by itself is not sufficient. Figure 1.9 demonstrates that there is in effect an evolution of integration from the stage 1 position of complete functional independence where each business function such as production or purchasing does their own thing in complete isolation from the other business functions. An example would be where production seeks to optimise its unit costs of manufacture by long production runs without regard for the build-up of finished goods inventory and heedless of the impact it will have on the need for warehousing space and the impact on working capital.

Stage 2 companies have recognised the need for at least a limited degree of integration between adjacent functions, e.g. distribution and inventory management or purchasing and materials control. The natural next step to stage 3 requires the establishment and implementation of an ‘end-to-end’ planning framework that will be fully described later in Chapter 5.

Stage 4 represents true supply chain integration in that the concept of linkage and co-ordination that is achieved in stage 3 is now extended upstream to suppliers and downstream to customers.

The changing competitive environment

As the competitive context of business continues to change, bringing with it new complexities and concerns for management generally, it also has to be recognised that the impact on logistics and supply chain management of these changes can be considerable. Indeed, of the many strategic issues that confront the business organisation today, perhaps the most challenging are in the area of logistics and supply chain management.

Figure 1.9 Achieving an integrated supply chain

Source: Reprinted with permission from Emerald Group Publishing Limited, originally published in Stevens, G. C., ‘Integrating the supply chain’, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Materials Management, 19(8) © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 1989

Much of this book will be devoted to addressing these challenges in detail but it is useful at this stage to highlight what are perhaps the most pressing current issues. These are:

- The new rules of competition

- Turbulence and volatility

- Globalisation of industry

- Downward pressure on price

The new rules of competition

We are now entering the era of ‘supply chain competition’. The fundamental difference from the previous model of competition is that an organisation can no longer act as an isolated and independent entity in competition with other similarly ‘stand-alone’ organisations. Instead, the need to create value delivery systems that are more responsive to fast-changing markets and are much more consistent and reliable in the delivery of that value requires that the supply chain as a whole be focused on the achievement of these goals.

In the past, the ground rules for marketing success were obvious: strong brands backed up by large advertising budgets and aggressive selling. This formula now appears to have lost its power. Instead, the argument is heard, companies must recognise that increasingly it is through their capabilities and competencies that they compete.

Essentially, this means that organisations create superior value for customers and consumers by managing their core processes better than competitors manage theirs. These core processes encompass such activities as new product development, supplier development, order fulfilment and customer management. By performing these fundamental activities in a more cost-effective way than competitors, it is argued, organisations will gain the advantage in the marketplace.

For example, one capability that is now regarded by many companies as fundamental to success in the marketplace is supply chain agility. As product life cycles shorten, as customers adopt JIT practices and as sellers’ markets become buyers’ markets then the ability of the organisation to respond rapidly and flexibly to demand can provide a powerful competitive edge. This is a theme to which we will return in Chapter 6.

A major contributing factor influencing the changed competitive environment has been the trend towards ‘commoditisation’ in many markets. A commodity market is characterised by perceived product equality in the eyes of customers resulting in a high preparedness to substitute one make of product for another. Research increasingly suggests that consumers are less loyal to specific brands but instead will have a portfolio of brands within a category from which they make their choice. In situations such as this, actual product availability becomes a major determinant of demand. There is evidence that more and more decisions are being taken at the point of purchase and if there is a gap on the shelf where brand X should be, but brand Y is there instead, then there is a strong probability that brand Y will win the sale.

It is not only in consumer markets that the importance of logistics process excellence is apparent. In business-to-business and industrial markets it seems that product or technical features are of less importance in winning orders than issues such as delivery lead-times and flexibility. This is not to suggest that product or technical features are unimportant – rather it is that they are taken as a ‘given’ by the customer. Quite simply, in today’s marketplace the order-winning criteria are more likely to be service-based than product-based.

A parallel development in many markets is the trend towards a concentration of demand. In other words, customers – as against consumers – are tending to grow in size whilst becoming fewer in number. The retail grocery industry is a good example: in most northern European countries a handful of large retailers account for over 50 per cent of all sales. This tendency towards the concentration of buying power is accelerating as a result of global mergers and acquisitions. The impact of these trends is that these more powerful customers are becoming more demanding in terms of their service requirements from suppliers.

At the same time as the power in the distribution channel continues to shift from supplier to buyer, there is also a trend for customers to reduce their supplier base. In other words they want to do business with fewer suppliers and often on a longer-term basis. The successful companies in the coming years will be those that recognise these trends and seek to establish strategies based upon establishing closer relationships with key accounts. Such strategies will focus upon seeking innovative ways to create more value for these customers.

Building competitive platforms that are based upon this idea of value-based growth will require a much greater focus on managing the core processes that we referred to earlier. Whereas the competitive model of the past relied heavily on product innovation, this will have to be increasingly supplemented by process innovation. The basis for competing in this new era will be:

Figure 1.10 suggests that traditionally, for many companies, the investment has mainly been in product excellence and less in process excellence.

This is not to suggest that product innovation should be given less emphasis – far from it – but rather that more emphasis needs to be placed on developing and managing processes that deliver greater value for key customers.

We have already commented that product life cycles are getting shorter. What we have witnessed in many markets is the effect of changes in technology and consumer demand combining to produce more volatile markets where a product can be obsolete almost as soon as it reaches the market. There are many current examples of shortening life cycles but perhaps the personal computer (PC) symbolises them all. In this particular case we have seen rapid developments in technology that have first created markets where none existed before and then almost as quickly have rendered themselves obsolete as the next generation of product is announced.

Figure 1.10 Investing in process excellence yields greater benefits

Such shortening of life cycles creates substantial problems for logistics and supply chain management. In particular, shorter life cycles demand shorter lead-times – indeed our definition of lead-time may well need to change. Lead-times are traditionally defined as the elapsed period from receipt of customer order to delivery. However, in today’s environment there is a wider perspective that needs to be taken. The real lead-time is the time taken from the drawing board, through procurement, manufacture and assembly to the end market. This is the concept of strategic lead-time and the management of this time span is the key to success in managing logistics operations.

There are already situations arising where the life cycle is shorter than the strategic lead-time. In other words the life of a product on the market is less than the time it takes to design, procure, manufacture and distribute that same product! The implications of this are considerable both for planning and operations. In a global context, the problem is exacerbated by the longer transportation times involved.

Ultimately, therefore, the means of achieving success in such markets is to accelerate movement through the supply chain and to make the entire logistics system far more flexible and thus responsive to these fast-changing markets.

Turbulence and volatility

There is clear evidence6 that since the opening years of the 21st century we have moved into a world characterised by higher levels of turbulence and volatility. The causes of this changed backdrop to the business environment are many and varied – a combination of economic factors, geo-political upheavals, extended global supply chains and increased exposure to the risk of disruptions, to name just a few. Whatever the reasons for this heightened turbulence and volatility, its impact is clear: greater uncertainty.

The impact of this uncertainty is that it presents a challenge to the classic business model which is heavily reliant on forecasts. Traditionally, much of logistics management is forecast-driven. That is, we seek to predict the future usually on the basis of the past. The results of that forecast will generally determine decisions on how much inventory to build and to hold. This conventional model works well under conditions of stability, however it becomes less tenable under conditions of uncertainty.

It is not only uncertainty about demand that is the problem but also uncertainty about supply. Supply uncertainty may originate from product shortages, fluctuating commodity prices, supply chain disruptions, the failure of a suppliers’ business, and so on. Supply chain risk will be addressed in more detail in Chapter 12 but it is clearly the case that upstream volatility and turbulence have led to greater uncertainty on the supply side of the business.

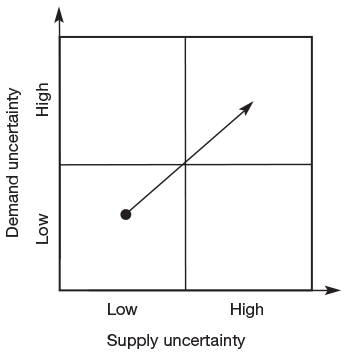

Figure 1.11 highlights how, in many cases, companies now face higher levels of uncertainly both upstream and downstream in their supply chains.

The implications of these changed conditions are significant. For logistics and supply chain managers it necessitates an urgent need to transform the business from a forecast-driven model to one that is demand-driven. In subsequent chapters we will identify some of the ways in which this transition can be facilitated.

Figure 1.11 Demand and supply uncertainty

Globalisation of industry

A further strategic issue that provides a challenge for logistics management is the continued trend towards globalisation.

A global company is more than a multinational company. In a global business, materials and components are sourced worldwide and products may be manufactured offshore and sold in many different countries, perhaps with local customisation.

Such is the trend towards globalisation, it is probably safe to forecast that before long most markets will be dominated by global companies. The only role left for national companies will be to cater for specific and unique local demands, for example in the food industry.

For global companies like Hewlett Packard, Philips and Caterpillar, the management of the logistics process has become an issue of central concern. The difference between profit and loss for an individual product can hinge upon the extent to which the global pipeline can be optimised, because the costs involved are so great. The global company seeks to achieve competitive advantage by identifying world markets for its products and then to develop a manufacturing and logistics strategy to support its marketing strategy. So a company like Caterpillar, for example, has dispersed assembly operations to key overseas markets and uses global logistics channels to supply parts to offshore assembly plants and after-markets. Where appropriate, Caterpillar will use third-party companies to manage distribution and even final finishing. So, for example, in the United States a third-party company, in addition to providing parts inspection and warehousing, attaches options to fork lift trucks. Wheels, counterweights, forks and masts are installed as specified by Caterpillar. Thus local market needs can be catered for from a standardised production process.

Globalisation also tends to lengthen supply chains as companies increasingly move production offshore or source from more distant locations. The impetus for this trend, which in recent years has accelerated dramatically, is the search for lower labour costs. However, one implication of these decisions is that ‘end-to-end’ pipeline times may increase significantly. In time-sensitive markets, longer lead-times can be fatal.

‘Time-based competition’ is an idea that will be returned to many times in later chapters. Time compression has become a critical management issue. Product life cycles are shorter than ever, customers and distributors require JIT deliveries and end users are ever-more willing to accept a substitute product if their first choice is not instantly available.

The globalisation of industry, and hence supply chains, is inevitable. However, to enable the potential benefits of global networks to be fully realised, a wider supply chain perspective must be adopted. It can be argued that for the global corporation competitive advantage will increasingly derive from excellence in managing the complex web of relationships and flows that characterise their supply chains.

Downward pressure on price

Whilst the trend might not be universal there can be no doubt that most markets are more price competitive today than they were a decade ago. Prices on the high street and in shopping malls continue to fall in many countries.

Whilst some of this price deflation can be explained as the result of normal cost reduction through learning and experience effects, the rapid fall in the price of many products has other causes.

First, there are new global competitors who have entered the marketplace supported by low-cost manufacturing bases. The dramatic rise of China as a major producer of quality consumer products is evidence of this. Secondly, the removal of barriers to trade and the deregulation of many markets has accelerated this trend, enabling new players to rapidly gain ground. One result of this has been overcapacity in many industries. Overcapacity implies an excess of supply over demand and hence leads to further downward pressure on price.

A further cause of price deflation, it has been suggested, is the Internet, which makes price comparison so much easier. The Internet has also enabled auctions and exchanges to be established at industry-wide levels, which have also tended to drive down prices.

In addition, there is evidence that customers and consumers are more value conscious than has hitherto been the case. Brands and suppliers that could once command a price premium because of their perceived superiority can no longer do so as the market recognises that equally attractive offers are available at significantly lower prices. The success of many retailers’ own-label products or the inroads made by low-cost airlines proves this point.

Against the backdrop of a continued downward pressure on price, it is self-evident that, in order to maintain profitability, companies must find a way to bring down costs to match the fall in price.

The challenge to the business is to find new opportunities for cost reduction when, in all likelihood, the company has been through many previous cost-reduction programmes. It can be argued that the last remaining opportunity of any significance for major cost reduction lies in the wider supply chain rather than in the firm’s own internal operations.

This idea is not new; back in 1929, Ralph Borsodi7 expressed it in the following words:

In 50 years between 1870 and 1920 the cost of distributing necessities and luxuries has nearly trebled, while production costs have gone down by one-fifth … What we are saving in production we are losing in distribution.

The situation that Borsodi describes can still be witnessed in many industries today. For example, companies that thought they could achieve a leaner operation by moving to JIT practices often only shifted costs elsewhere in the supply chain by forcing suppliers or customers to carry that inventory. The car industry, which to many is the home of lean thinking and JIT practices, has certainly exhibited some of those characteristics. An analysis of the western European automobile industry showed that whilst car assembly operations were indeed very lean with minimal inventory, the same was not true upstream and downstream of those operations. Figure 1.12 shows the profile of inventory through the supply chain from the tier 1 suppliers down to the car dealerships.

In this particular case the paradox is that most inventory is being held where it is at its most expensive, i.e. as a finished product. The true cost of this inventory to the industry is considerable. Whilst inventory costs will vary by industry and by company, it will be suggested in Chapter 4 that the true cost of carrying inventory is rarely less that 25 per cent per year of its value. In the difficult trading conditions facing many companies, this alone is enough to make the difference between profit and loss.

This example illustrates the frequently encountered failure to take a wider view of cost. For many companies their definition of cost is limited only to those costs that are contained within the four walls of their business entity. However, as has been suggested earlier, as today’s competition takes place not between companies but between supply chains, the proper view of costs has to be ‘end-to-end’ because all costs will ultimately be reflected in the price of the finished product in the final marketplace.

The need to take a supply chain view of cost is further underscored by the major trend towards outsourcing that is observable across industries worldwide. For many companies today, most of their costs lie outside their legal boundaries; activities that used to be performed in-house are now outsourced to specialist service providers. The amazing growth of contract manufacturing in the consumer electronics sector bears witness to this trend. If the majority of an organisation’s costs lie outside the business then it follows that the biggest opportunities for improvement in their cost position will also be found in that wider supply chain.

Figure 1.12 Inventory profile of the automotive supply chain

Source: Holweg, M. and Pil, F.K., The Second Century, MIT Press, 20048

The customers take control

So much has been written and talked about service, quality and excellence, and there is no escaping the fact that the customer in today’s marketplace is more demanding, not just of product quality, but also of service.

As more and more markets become, in effect, ‘commodity’ markets, where the customer perceives little technical difference between competing offers, the need is for the creation of differential advantage through added value. Increasingly a prime source of this added value is through customer service.

Customer service may be defined as the consistent provision of time and place utility. In other words, products don’t have value until they are in the hands of the customer at the time and place required. There are clearly many facets of customer service, ranging from on-time delivery through to after-sales support. Essentially the role of customer service should be to enhance ‘value-in-use’, meaning that the product becomes worth more in the eyes of the customer because service has added value to the core product. In this way significant differentiation of the total offer (that is the core product plus the service package) can be achieved.

Those companies that have achieved recognition for service excellence, and thus have been able to establish a differential advantage over their competition, are typically those companies where logistics management is a high priority. Companies like Xerox, Zara and Dell are typical of such organisations. The achievement of competitive advantage through service comes not from slogans or expensive so-called customer care programmes, but rather from a combination of a carefully thought-out strategy for service, the development of appropriate delivery systems and commitment from people, from the chief executive down.

The attainment of service excellence in this broad sense can only be achieved through a closely integrated logistics strategy. In reality, the ability to become a market leader depends as much upon the effectiveness of one’s operating systems as it does upon the presentation of the product, the creation of images and the influencing of consumer perceptions. In other words, the success of McDonald’s, Wal-Mart or any of the other frequently cited paragons of service excellence is due not to their choice of advertising agency, but rather to their recognition that managing the logistics of service delivery on a consistent basis is the crucial source of differential advantage.

Managing the ‘4Rs’

As we move rapidly into the era of supply chain competition a number of principles emerge to guide the supply chain manager. These can be conveniently summarised as the ‘4Rs’ of responsiveness, reliability, resilience and relationships.

1 Responsiveness

In today’s JIT world, the ability to respond to customers’ requirements in ever-shorter time-frames has become critical. Not only do customers want shorter lead-times, they are also looking for flexibility and increasingly customised solutions. In other words, the supplier has to be able to meet the precise needs of customers in less time than ever before. The key word in this changed environment is agility. Agility implies the ability to move quickly and to meet customer demand sooner. In a fast-changing marketplace, agility is actually more important than long-term planning in its traditional form. Because future demand patterns are uncertain, by definition this makes planning more difficult and, in a sense, hazardous.

In the future, organisations must be much more demand-driven than forecast-driven. The means of making this transition will be through the achievement of agility, not just within the company but across the supply chain. Responsiveness also implies that the organisation is close to the customer, hearing the voice of the market and quick to interpret the demand signals it receives.

2 Reliability

One of the main reasons why any company carries safety stock is because of uncertainty. It may be uncertainty about future demand or uncertainty about a supplier’s ability to meet a delivery promise, or about the quality of materials or components. Significant improvements in reliability can only be achieved through re-engineering the processes that impact performance. Manufacturing managers long ago discovered that the best way to improve product quality was not by quality control through inspection but rather to focus on process control. The same is true for logistics reliability.

One of the keys to improving supply chain reliability is through reducing process variability. In recent years there has been a considerable increase in the use of so-called ‘Six Sigma’ methodologies. The concept of Six Sigma will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 12, but in essence these tools are designed to enable variability in a process to be reduced and controlled. Thus, for example, if there is variability in order processing lead-times then the causes of that variability can be identified and where necessary the process can be changed and brought under control through the use of Six Sigma tools and procedures.

3 Resilience

As we have already commented, today’s marketplace is characterised by higher levels of turbulence and volatility. The wider business, economic and political environments are increasingly subjected to unexpected shocks and discontinuities. As a result, supply chains are vulnerable to disruption and, in consequence, the risk to business continuity is increased.

Whereas in the past the prime objective in supply chain design was probably cost minimisation or possibly service optimisation, the emphasis today has to be upon resilience. Resilience refers to the ability of the supply chain to cope with unexpected disturbances. There is evidence that the tendencies of many companies to seek out low-cost solutions because of pressure on margins may have led to leaner, but more vulnerable, supply chains.

Resilient supply chains may not be the lowest-cost supply chains but they are more capable of coping with the uncertain business environment. Resilient supply chains have a number of characteristics, of which the most important is a business-wide recognition of where the supply chain is at its most vulnerable. Managing the critical nodes and links of a supply chain, to be discussed further in Chapter 12, becomes a key priority. Sometimes these ‘critical paths’ may be where there is dependence on a single supplier, or a supplier with long replenishment lead-times, or a bottleneck in a process.

Other characteristics of resilient supply chains are their recognition of the importance of strategic inventory and the selective use of spare capacity to cope with ‘surge’ effects.

4 Relationships

The trend towards customers seeking to reduce their supplier base has already been commented upon. In many industries the practice of ‘partnership sourcing’ is widespread. It is usually suggested that the benefits of such practices include improved quality, innovation sharing, reduced costs and integrated scheduling of production and deliveries. Underlying all of this is the idea that buyer/supplier relationships should be based upon partnership. Increasingly companies are discovering the advantages that can be gained by seeking mutually beneficial, long-term relationships with suppliers. From the suppliers’ point of view, such partnerships can prove formidable barriers to entry for competitors. The more that processes are linked between the supplier and the customer the more the mutual dependencies increase and hence the more difficult it is for competitors to break in.

Supply chain management, by definition, is about the management of relationships across complex networks of companies that, whilst legally independent, are in reality interdependent. Successful supply chains will be those that are governed by a constant search for win-win solutions based upon mutuality and trust. This is not a model of relationships that has typically prevailed in the past. It is one that will have to prevail in the future as supply chain competition becomes the norm.

These four themes of responsiveness, reliability, resilience and relationships provide the basis for successful logistics and supply chain management. They are themes that will be explored in greater detail later in this book.

References

1. Bowler, R.A., Logistics and the Failure of the British Army in America 1775–1783, Princeton University Press, 1975.

2. Shaw, A.W., Some Problems in Market Distribution, Harvard University Press, 1915.

3. Oliver R.K. and Webber, M.D., Supply-Chain management: logistics catches up with strategy, Outlook, 1982. Reprinted in Christopher, M., Logistics: The Strategic Issues, Chapman and Hall 1992.

4. Aitken, J., Supply Chain Integration within the Context of a Supplier Association, Cranfield University, Ph.D. Thesis, 1998.

5. Porter, M.E., Competitive Advantage, The Free Press, 1985.

6. Christopher, M. and Holweg, M., ‘Supply Chain 2.0: Managing Supply Chains in the Era of Turbulence’, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, Vol 41, No. 1, 2011.

7. Borsodi, R., The Distribution Age, D. Appleton & Co, 1929.

8. Holweg, M. and Pil, F.K., The Second Century, MIT Press, 2004.