Derivatives and options

Derivatives – options, futures, warrants, etc – are the subject of this chapter and the next two. Derivative instruments have become increasingly important for professional investors over the last 30 years. However, they are not just the province of professionals. Private investors can also exploit these powerful tools to either reduce risk or to go in search of high returns. Naturally, exceptionally high returns come with exceptionally high risk. So traders using derivatives for this purpose need to understand the risk they are exposed to. Many people (and giant companies) have lost fortunes by allowing themselves to be mesmerised by the potential for riches while failing to take the time to fully understand the instruments they were buying. They jumped in, unaware of or ignoring the potential for enormous loss.

Here we describe the main types of derivatives and show how they can be used for controlling risk (hedging) and for revving-up returns (speculation). We also try to convey the downside so that investors can go into these markets with their eyes open.

What is a derivative?

A derivative instrument is an asset whose performance is based on (derived from) the behaviour of the value of an underlying asset (usually referred to simply as the ‘underlying’). The most common underlyings are commodities (tea or pork bellies), shares, bonds, share indices, currencies and interest rates. Derivatives are contracts which give the right, and sometimes the obligation, to buy or sell a quantity of the underlying, or benefit in another way from a rise or fall in the value of the underlying. It is the legal right that becomes an asset, with its own value, and it is the right that is purchased or sold.

Derivatives instruments have been employed for more than two thousand years. Olive growers in ancient Greece, unwilling to accept the risk of a low price for their crop when harvested months later, would enter into forward agreements whereby a price was agreed for delivery at a specific time. This reduced uncertainty for both the grower and the purchaser of the olives. In the Middle Ages forward contracts were traded in a kind of secondary market, particularly for wheat in Europe. A futures market was established in Osaka’s rice market in Japan in the seventeenth century. Tulip bulb options were traded in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.

Commodity futures trading really began to take off in the nineteenth century with the Chicago Board of Trade regulating the trading of grains and other futures and options, and the London Metal Exchange dominating metal trading.

So derivatives are not new. What is different today is the size and importance of the derivatives markets. We have witnessed an explosive growth in volumes of trade, the variety of derivatives products, and the number and range of users and uses.

What is an option?

An option is a contract giving one party the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a financial instrument, commodity or some other underlying asset at a given price, at or before a specified date. The purchaser of the option can either exercise the right or let it lapse – the choice is theirs.

A very simple option would be where a firm pays the owner of a piece of land a non-returnable premium (say, £10,000) for an option to buy the land at an agreed price (say, £1 million) because the firm is considering the development of a retail park within the next five years. The property developer may pay a number of option premiums to owners of land in different parts of the country. If planning permission is eventually granted on a particular plot the option to purchase may be exercised. In other words, the developer pays the price agreed at the time that the option contract was arranged, to purchase the land. Options on other plots will be allowed to lapse and will have no value. By using an option the property developer has ‘kept the options open’ with regard to which site to buy and develop and, indeed, whether to enter the retail park business at all.

Options can also be traded. Perhaps the option to buy could be sold to another company keener to develop a particular site than the original option purchaser. It may be sold for much more than the original £10,000 option premium, even before planning permission has been granted.

Once planning permission has been granted the site may be worth £1.5 million. If there is an option to buy at £1 million the option right has an intrinsic value of £500,000, representing a 4,900 per cent return on £10,000. From this we can see the gearing effect of options: very large sums can be gained in a short period of time for a small initial cash outlay.

Share options

Share options have been traded for centuries but their use expanded significantly with the creation of traded option markets in Chicago, Amsterdam and, in 1978, the London Traded Options Market, now incorporated into ICE Futures Europe.

A share call option gives the purchaser a right, but not the obligation, to buy a fixed number of shares at a specified price at some time in the future. In the case of traded options on ICE Futures Europe, one option contract relates to a quantity of 1,000 shares. The seller of the option, who receives the premium, is referred to as the writer. The writer of a call option is obliged to sell the agreed quantity of shares at the agreed price sometime in the future. American-style options can be exercised by the buyer at any time up to the expiry date, whereas European-style options can only be exercised on a predetermined future date. Just to confuse everybody, the distinction has nothing to do with geography: most options traded in Europe are American-style options.

Call option holders (call option buyers)

Now let us examine the call options available on an underlying share, Unilever on 1 August 2017. There are a number of different options available for this share, many of which are not reported in the table presented at www.ft.com (the original source is www.theice.com/products), part of which is reproduced below.

Table 8.1 Call options on Unilever shares, 1 August 2017

| Call option prices (premiums) in pence | |||

| Expiry month | September | December | March |

| Exercise price | |||

| 2500p | 72.5 | 87.5 | 101.5 |

| 2600p | 13.5 | 36.5 | 51.0 |

| Share price on 1 August 2017 = 2567p | |||

So, what do the figures mean? If you wished on 1 August 2017 to obtain the right to buy 1,000 shares on or before late December 20171 at an exercise price of 2600p, you would pay a premium of £365 (1,000 × 36.5p). If you wished to keep your option to purchase open for another three months you could select the March call. But this right to insist that the writer sells the shares at the fixed price of 2600p on or before a date in late March will cost another £145 (the total premium payable on one option contract is £510 rather than £365). This extra £145 represents additional time value. Time value arises because of the potential for the market price of the underlying to change in a way that creates intrinsic value.

The intrinsic value of an option is the pay-off that would be received if the underlying were at its current level when the option expires. In this case, there is currently (1 August) no intrinsic value because the right to buy is at 2600p whereas the share price is 2567p. However, if you look at the call option with an exercise price of 2500p, then the right to buy at 2500p has intrinsic value because if you purchased at £25 by exercising the option you could immediately sell at £25.67 in the share market. The intrinsic value is therefore 67p per share, or £670 for 1,000 shares. The longer the time over which the option is exercisable, the greater the chance that the price will move to give intrinsic value – this explains the higher premiums on more distant expiry options. Time value is the amount by which the option premium exceeds the intrinsic value.

The two exercise price (also called strike price) levels presented in Table 8.1 illustrate an in-the-money option (the 2500 call options) and an out-of-the-money option (the 2600 call options). The underlying share price (2567p) is above the strike price of 2500 and so the 2500p call option has an intrinsic value of 67p and is therefore in-the-money. The right to buy at 2600p is out-of-the-money because the share price is below the call option exercise price and therefore has no intrinsic value. The holder of a 2600p option would not exercise this right to buy at 2600p because the shares can be bought on the stock exchange for 2567p. (It is sometimes possible to buy an at-the-money option, which is one where the market share price is equal to the option exercise price.)

To emphasise the key points: option premiums vary in proportion to the length of time over which the option is exercisable (for example, they are higher for a March option than for a December option). Also, call options with lower exercise prices will have a higher premium.

Example - Option premiums

Suppose on 1 August you are confident that Unilever shares are going to rise over the next eight months to £30 and you purchase a March 2500 call at 101.5p.2 The cost of this right to purchase 1,000 shares is £1015 (101.5p x 1,000 shares). If the share rises as expected then you could exercise the right to purchase the shares for a total of £25,000 and then sell them in the market for £30,000. A profit of £5000 less the option premium of £1015 (i.e. £3,985) is made before transaction costs (the brokers’ fees, etc. would be in the region of £20–£50). This represents a massive 393 per cent rise on the £1,015 premium paid.

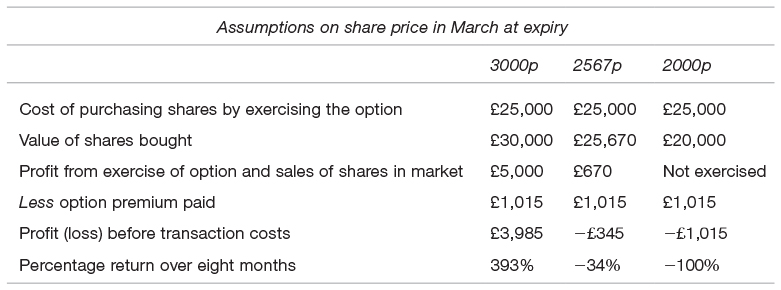

However, the future is uncertain and the share price may not rise as expected. Let us consider two other possibilities. First, the share price may remain at 2567p throughout the life of the option. Second, the stock market may have a downturn and Unilever shares may fall to 2000p. These possibilities are shown below.

Table 8.2 Profits and losses on the Unilever March 2018 call option following purchase on 1 August 2017

In the case of a standstill in the share price, the option gradually loses its time value over the eight months until, at expiry, only the intrinsic value of 67p per share remains. The fall in the share price to 2000p illustrates one of the advantages of purchasing options over some other derivatives: the holder has a right to abandon the option and is not forced to buy the underlying shares at the option exercise price. This saves £5,000. It would have added insult to injury to be compelled to buy at £25,000 and sell at £20,000 after having already lost £1,015 on the premium for the purchase of the option.

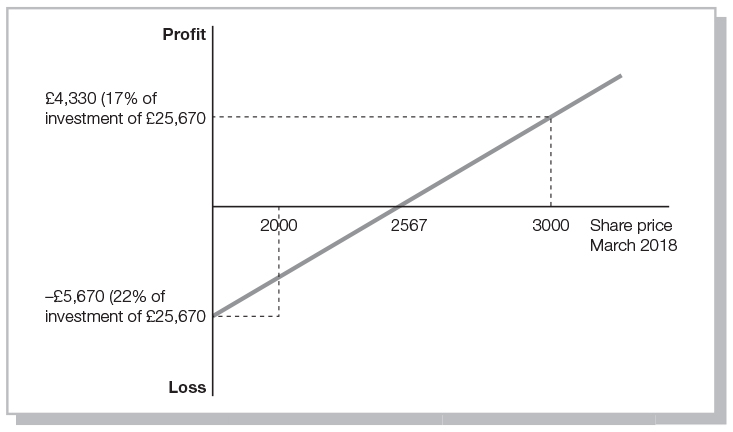

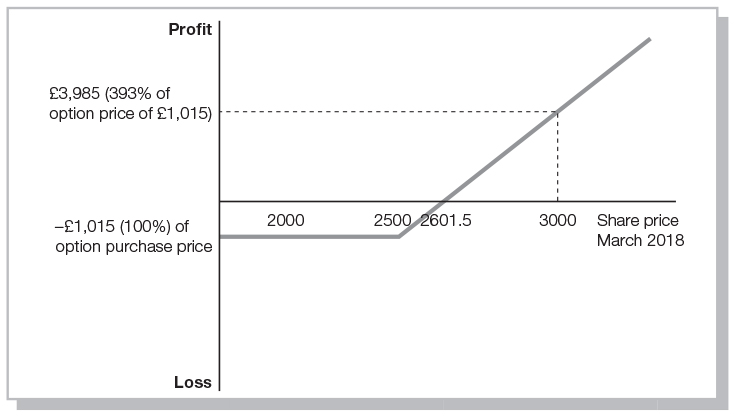

A comparison of Figures 8.1 and 8.2 shows the extent to which the purchase of an option gears up the return from share price movements: a wider dispersion of returns is experienced. On 1 August 2017, 1,000 shares could be bought for £25,670. If the value rose to £30,000, a 17 per cent return would be made, compared with a 393 per cent return if options are bought.

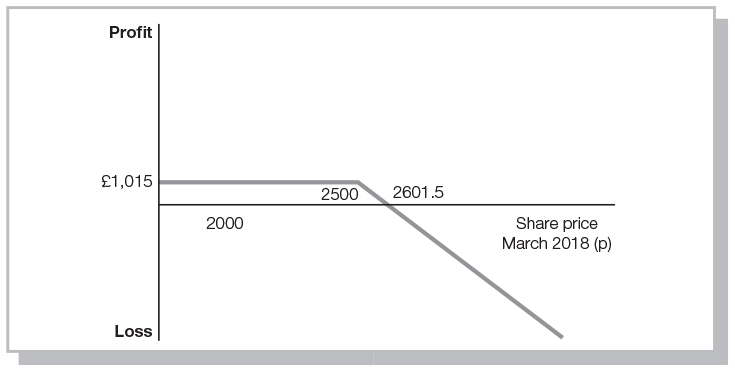

Figure 8.2 Profit if one March 2500 call option contract (for 1,000 shares) in Unilever is purchased 1 August 2017 and held to maturity

We would all like the higher positive return on the option than the lower one available on the underlying – but would we all accept the downside risk associated with this option? Consider the following possibilities. If the share price remains at 2567p, the return if shares are bought is 0 per cent, while the return if one 2500 March call option is bought is –34 per cent (the £1,015 paid for the option declines to its intrinsic value of only £670).3 If the share price falls to 2000p, then the return if shares are bought is –22 per cent, while the return if one 2500 March call option is bought is – 100% (the option is worth nothing).

The holder of the call option will not exercise unless the share price is at least 2500p. At a lower price it will be cheaper to buy the 1,000 shares on the stock market. Break-even does not occur until a price of 2601.5p because of the need to cover the cost of the premium (2500p + 101.5p). However, at higher prices the option value increases, penny for penny, with the share price. Also, the downside risk is limited to the size of the option premium.

Call option writers

The returns position for the writer of a call option in Unilever can also be presented in a diagram (see Figure 8.3). With all these examples remember that there is an assumption that the position is held to expiry.

Figure 8.3 The profit to a call option writer on one 2500 March 2018 call contract (for 1,000 shares written on 1 August 2017)

If the market price is less than the exercise price (2500p) in March the option will not be exercised and the call writer profits to the extent of the option premium (101.5p per share). A market price greater than the exercise price will result in the option being exercised and the writer will be forced to deliver 1,000 shares for a price of 2500p. This may mean buying shares on the stock market to supply to the option holder. As the share price rises this becomes increasingly onerous, and losses mount.

Note that in the sophisticated traded option markets of today very few option positions are held to expiry. In most cases the option holder sells the option in the market to make a cash profit or loss. Option writers often cancel out their exposure before expiry – for example, they could purchase an option to buy the same quantity of shares at the same price and expiry date.

Example - An option writing strategy

Joe has a portfolio of shares worth £100,000 and is confident that, while the market will go up steadily over time, it will not rise over the next few months. He has a strategy of writing out-of-the-money (i.e. no intrinsic value) call options and pocketing premiums on a regular basis.

Today (1 August 2017) Joe has written one option on March calls in Unilever for an exercise price of 2600p (current share price 2567p). In other words, Joe is committed to delivering (selling) 1,000 shares at any time between 1 August 2017 and the third Friday in March 2018 for a price of 2600p at the insistence of the person who bought the call. This could be very unpleasant for Joe if the market price rises to, say, 3500p. Then the option holder will require Joe to sell shares worth £35,000 to them for only £26,000. However, Joe is prepared to take this risk for two reasons. First he receives the premium of 51p per share up front – this is 2 per cent of each share’s value. This £510 will cushion any feeling of future regret at his actions. Second, Joe holds 1,000 Unilever shares in his portfolio and so would not need to go into the market to buy the shares to then sell them to the option holder if the price did rise significantly.

Joe has written a covered call option – so-called because he has backing in the form of the underlying shares. Joe only loses out if the share price on the day the option is exercised is greater than the strike price (2600p) plus the premium (51p). He is prepared to risk losing some of the potential upside (above 2600p + 51p = 2651p) to gain the premium. He also reduces his loss on the downside: if the shares in his portfolio fall he has the premium as a cushion.

Some speculators engage in uncovered (naked) option writing. This is not recommended for beginners as it is possible to lose a great deal of money – a multiple of your current resources if you write a lot of option contracts and the price moves against you. Imagine if Joe had only £10,000 in savings and entered the options market by writing 40 Unilever March 2018 2600 calls receiving a premium of 51p × 40 × 1,000 = £20,400.4 If the price moves to £28 Joe has to buy shares for £28 and then sell them to the option holders for £26, a loss of £2 per share: £2 × 40 × 1,000 = £80,000. Despite receiving the premiums Joe has wiped out his savings and is in considerable debt.

LIFFE share options

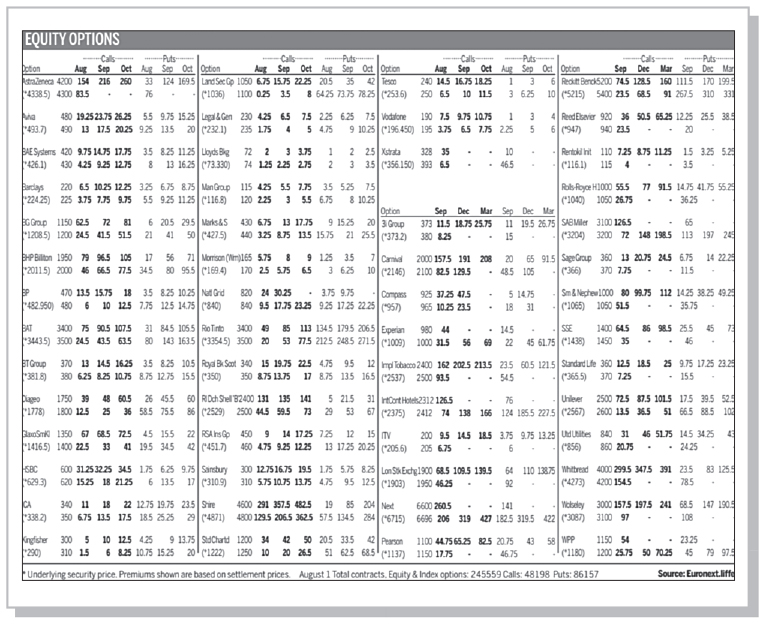

The Financial Times lists about 60 companies’ shares in which options are traded – some are shown below.

Box 8.1 - Equity options in the Financial Times

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 1 August 2017.

© The Financial Times Limited 2017. All Rights Reserved.

Put options

A put option gives the holder the right, but not the obligation, to sell a specific quantity of shares on or before a specified date at a fixed exercise price.

Imagine you are pessimistic about the prospects for Sainsbury on 1 August 2017. You could purchase, for a premium of 5.75p per share (£57.50 in total), the right to sell 1,000 shares before late September 2017 at 300p (see above). If a fall in price subsequently takes place, to 250p, say, you can insist on exercising the right to sell at 300p. The writer of the put option is obliged to purchase shares at 300p while being aware that the put holder is able to buy shares at 250p on the stock market. The option holder makes a profit of 50p per share less the 5.75p premium (44.25p per share or £442.50 in total), a 770 per cent return (before costs).

As with calls, in most cases the option holder would take profits by selling the option on to another investor via ICE Futures Europe rather than waiting to exercise at expiry.

For the put option holder, if the market price exceeds the exercise price, it will not be wise to exercise as shares can be sold for a higher price on the stock market. Therefore the maximum loss, equal to the premium paid, is incurred. The option writer gains the premium if the share price remains above the exercise price, but may incur a large loss if the market price falls significantly.

How to trade options

Your existing share dealing broker will probably be able to offer an option (and futures) dealing facility, with or without advice. If not, ask another broker. Minimum commissions are generally £20, but brokers do go lower in special promotional periods when in search of business. Expect to pay a bid–offer spread of between 1p and 3p per share on the premiums. So if a premium were quoted at 35p in the Financial Times, this will be a mid-price between the price you would pay if you were buying (offer price), say 36p, and the price you would receive if you were selling (bid price), say 34p.

Traded option prices for over 300 leading European companies are carried on the ICE Futures Europe website (www.theice.com/products), and are continuously updated, as they are on a number of financial websites. Traders can set limits on the price to pay when making an order. The price limits can be good for the day (if not fulfilled in a day, the order is cancelled) or good till cancelled.

Gains from option trading are taxable as capital gains. No stamp duty is levied on purchases.

Using share options to reduce risk: hedging

Hedging with options is especially attractive because they can give protection against unfavourable movements in the underlying while permitting the possibility of benefiting from favourable movements. Suppose you hold 1,000 shares in Sainsbury’s on 1 August 2017. Your shareholding is worth £3,109. There are rumours flying around the market that the company may become the target of a takeover bid. If this materialises, the share price will rocket. If it does not, the market will be disappointed and the price will fall dramatically. What are you to do? One way to avoid the downside risk is to sell the shares. The problem is that you may regret this action if the bid does subsequently occur and you have forgone the opportunity of a large profit. An alternative approach is to retain the shares and buy a put option. This will rise in value as the share price falls. If the share price rises you gain from your underlying shareholding.

Assume a 300 October put is purchased for a premium of £82.5 (see Equity options box above). If the share price falls to 250p in late October you lose on your underlying shares by £609 ((310.9p − 250p) × 1,000). However, the put option will have an intrinsic value of £500 ((300p − 250p) × 1,000), thus reducing the loss and limiting the downside risk. Below 300p, for every 1p lost on the share price, 1p is gained on the put option, so the maximum loss is £191.50 (£109 intrinsic value + £82.50 option premium).

This hedging reduces the dispersion of possible outcomes. There is a floor below which losses cannot be increased, while on the upside the benefit from any rise in share price is reduced due to the premium paid. If the share price stands still at 310.9p, however, you may feel that the premium you paid to insure against an adverse movement at 8.25p, or 2.7 per cent of the share price, was excessive. If you keep buying this type of ‘insurance’ through the year it can reduce your portfolio returns substantially.

Using options to reduce losses

A simpler example of risk reduction occurs when an investor is fairly sure that a share will rise in price but is not so confident as to discount the possibility of a fall. Suppose that the investor wished to buy 10,000 shares in Diageo, currently priced at 1,778p (on 1 August 2017) – see Equity options box above. This can be achieved either by a direct purchase of shares in the market or through the purchase of an option. If the share price does fall significantly, the size of the loss is greater with the share purchase – the option loss is limited to the premium paid. Suppose that on 1 August 2017 ten September 1750 call options are purchased at a cost of £4,800 (48p × 1,000 × 10). The table below shows that the option is less risky because of the ability to abandon the right to buy at 1750p.

Index options

Options on whole share indices can be purchased, for example, Standard and Poor’s 500 (US), FTSE 100 (UK), CAC 40 (France) and XETRA DAX (Germany). Large investors usually have a varied portfolio of shares so, rather than hedging individual shareholdings with options, they may hedge through options on the entire index of shares. Also speculators can take a position on the future movement of the market as a whole.

A major difference between index options and share options is that the former are ‘cash settled’ – so for the FTSE 100 option, there is no delivery of 100 different shares on the expiry day. Rather, a cash difference representing the price change changes hands.

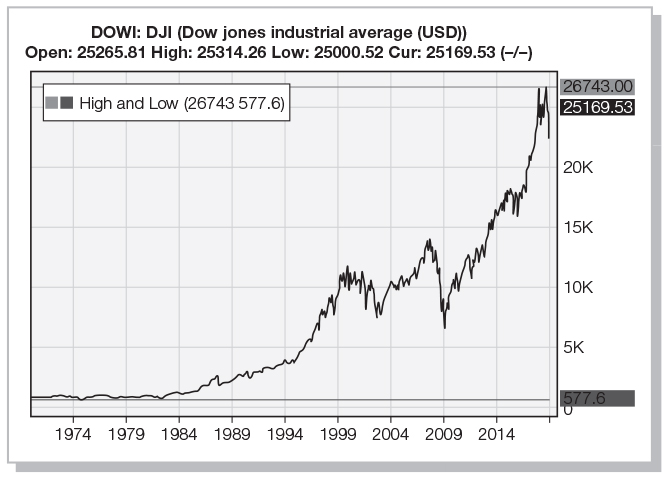

In between working on books, I invest in shares and write up my exploits in my investment newsletter on ADVFN (www.newsletters.advfn.com/deepvalueshares). In February 2019 I held a lot of UK shares but was worried that the US markets were over-extended. If they fell significantly there would be a ricochet effect around the world, pulling down my shares. So, I bought some ‘insurance’, purchasing put options on the Dow Jones Industrial Average share index. Here is what I wrote up for my subscribers.

Example - Protection against a fall in the equity market

Given the significant economic and business uncertainties roaming the world, alongside American equities being only slightly lower than in 1929 relative to company earnings over ten years, I’ve decided to buy some more insurance against a large drop in markets around the world.

I’ll continue to buy deep value UK shares, but also have in place a financial instrument that rises in value between ten- and fifty-fold should the Dow Jones fall by a large percentage. Thus, even if the price of my UK shares declines, I’ll be OK overall.

Tomorrow’s newsletter will describe the instrument I bought. Today, I briefly recap the reasons to worry about a major downturn, especially in the American share market.

Cyclically adjusted price earnings ratio

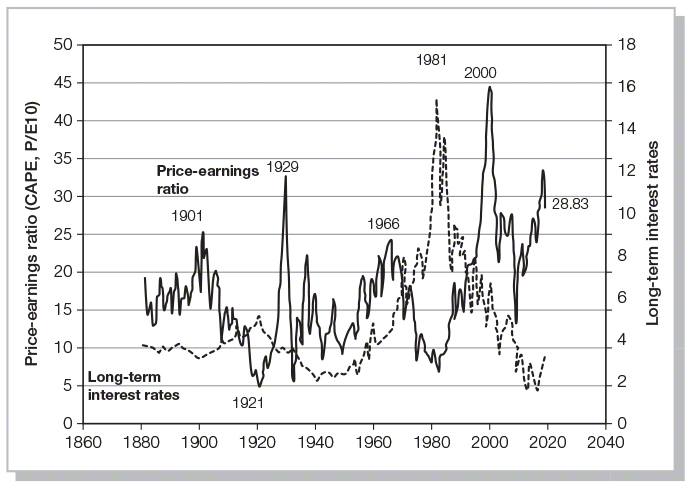

The first chart is taken from Professor Robert Shiller’s website. It measures the current share price divided by the average of the past ten years’ earnings per share.

The ratio has come off its highs of around 34 in 2018 due to recent rapid growth in earnings helped by the tax cut, but nevertheless, it remains around the same level as in 1929 and 1999, and much higher than at the 1966 or 2007 peaks.

Investors in American shares have high expectations of earnings growth over the next few years. Will they be fulfilled? Maybe. But there are some reasons to doubt continued resilience. I’ll outline a few of the possible triggers that might start a large slide in US shares:

1. Bank crisis?

“Nearly every banking crisis in the last thirty years has been associated with a decline in cross-border investment flows that led to a decline in the price of a country’s currency. Every country that experienced a banking crisis had previously experienced an economic boom. These booms morphed into busts when the investment flows stopped.” (Manias, Panics and Crashes (2015) by Kindleberger and Aliber.)

Is the flow of loans to America slowing?

The Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis recently wrote: “As long as a government runs deficits, it has to find buyers for its bonds. In the years after the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve was a willing buyer of U.S. Treasury bonds. Since 2014, though, the Fed has put its buying spree on hold. So, somebody else must be taking up the slack. But who? Contrary to some reports, foreigners are not soaking up federal government debt. It seems to be domestic private investors, given that their holdings have continued increasing, while foreigners’ holdings have not.” We thus have an indicator that foreigners are less willing to fund American borrowing.

US Gross Domestic Product is around $21tn and total government debt (including the $13.5tn of Federal debt) is also $21tn, that is $64,000 per man woman and child – 40% of it is owed to foreigners.

2. Danger in corporate debt levels

The debt of US companies is double the level of 2008 ($3tn in 2008 and $6tn in 2019), when the last crisis set in – the economy has grown by about one-third in the last decade.

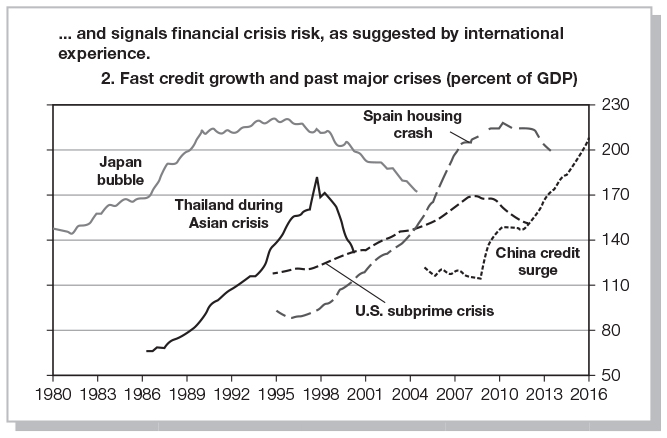

3. China’s debt surge is unsustainable

China has vast amounts of debt outstanding, and the surge in its debt fits a familiar pattern – see chart.

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, International Monetary Fund, April 2017

4. Housing property markets around the world are suffering

A loss of consumer confidence may follow.

5. The Minsky moment

Hyman Minsky observed that the supply of credit was pro-cyclical – when the economy is booming banks and other lenders become much more willing to lend, when it is in a recession they pull in their horns and become very reluctant to advance loans.

Similarly, investors in real estate or securities become increasingly optimistic as the economy expands about their potential returns; they become more willing to borrow to invest.

There is usually a simple story to help generate optimism, e.g. the new economic era in the US in 1999, the East Asian miracle in the mid-1990s.

When the economy slows share investors become more pessimistic, alongside the lenders, and so are less eager to engage in debt finance.

This pro-cyclicality leads to fragility. Investors who expected that large increases in the prices of their investments would greatly out-weigh the cost of the interest borrowed to invest in them, suddenly find they are wrong when the economy grows less fast. Later, many become distressed sellers as they observe property and security prices declining.

6. Chinese shadow banking

Private sector Chinese lenders and borrowers are by-passing the banking system by investing/issuing risky short-term instruments, e.g. “wealth management products”. The parallel system pumping money from savers into banks, insurance companies, local authorities and corporations, might prove to be built on sand – short-term loans, which are then used to buy all sorts of assets from land in China to UK companies and property. The whole system relies on a regular rolling-over of those loans.

7. War, e.g. caused by an unpredictable Trump.

8. European recession caused by (a) China slowdown and trade wars and (b) Brexit.

9. Leveraged loans and junk bonds currently offer remarkably low interest rates with virtually no covenants. This is caused by excessive confidence in highly leveraged companies following a benign economic phase. Such confidence can evaporate.

10. A well-loved company with an exceptional influence on investor mood disappoints the market greatly, stimulating thoughts that disappointments will hit investors from elsewhere, leading to mood of caution., e.g. Apple (I hear already that teenagers are more enamoured with alternatives and Chinese/other buyers are recoiling at the price).

11. Trade war, which becomes very intense because it is merely a symptom of China/US rivalry.

12. Something completely off the radar, something we haven’t even thought about.

The options bought

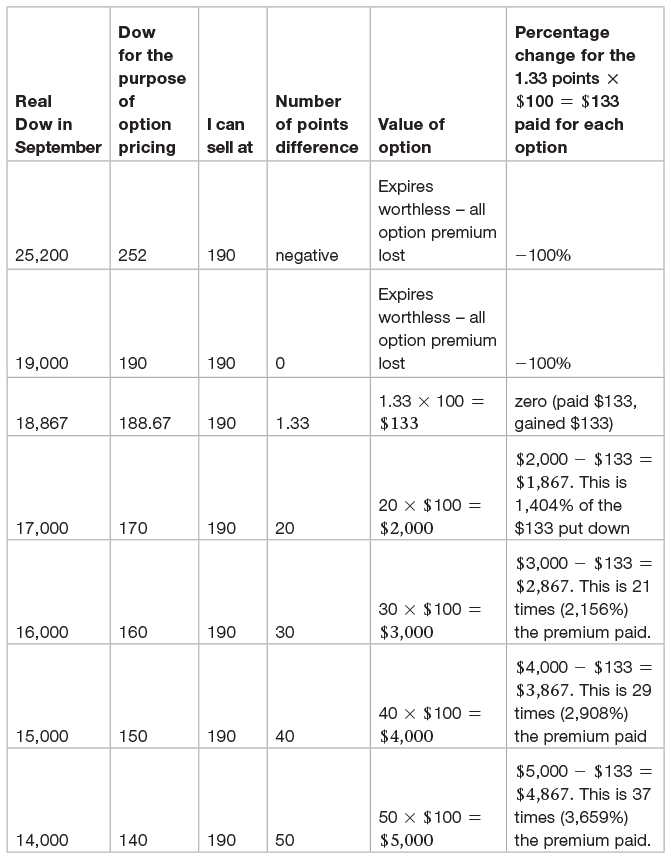

On Thursday I bought put options on the Dow Jones Industry Average Index. The exercise price is 190 and this right to exercise expires on the third Friday in September. I’ll explain.

Let’s start with what a put option is: a right, but not an obligation, to sell the underlying at a fixed price at some point in the future or over a period of time.

Source: www.advfn.com

Applying that to the Dow: the underlying, i.e. the DJIA stands at 25,200 today. A put option gives me the right to sell the Dow at a set price in September.

A complication: instead of the straightforward Dow the DJIA number is divided by 100 for the option contract. Thus if the real Dow is at 25,200 the option that is ‘at the money’ is expressed as 252. Each of those points is worth $100.

I’ll illustrate with the put that I purchased on Thursday: I bought the right but not the obligation to sell at 190. If I was to go ahead and exercise my right I would fork out 190 × $100 = $19,000.

But, with index options I do not have to buy the underlying because these are what is called ‘cash settled’. That is, only the difference between 190 and the value at expiry is paid over in cash (I don’t sell 30 different company shares). Obviously, I would not want to exercise the right to sell at 190 when the market is at 252. This means that the option does not have intrinsic value (it is ‘out of the money’).

If I had bought a 260 put option instead I would have the right to sell at 260 × $100 = $26,000 and I could buy that index at 252 × $100 = £25,200. This put option has intrinsic value of 8 points or $800 (it is ‘in the money’).

But such an option costs a lot more than the heavily out of the money one I did buy. I paid 1.33 points for the right to sell at 190. Those 190 points are worth 190 × $100 = $19,000, whereas my option cost 1.33 × $100 = $133. This is only 0.5% of the underlying.

I have between now and the third Friday in September for my option to gain some intrinsic value. It will not do so if the Dow stays above 19,000.

So, if the underlying fell to 180 (that is 18,000 on the real Dow) I would have the right to sell at 190 while being able to ‘buy’ at 180. The market organiser (CBOE in Chicago) will cash settle with me for 10 points per contract (190–180), each point worth $100, thus sending me $1,000 in September.

Thus, I have a highly geared position on the Dow. For a large range of Dow values in September I receive nothing, but when (or, rather, IF) the Dow falls below 19,000 I start to gain quite high percentages. If the Dow falls all the way to 14,000, off about 44% from its current level, then the amount I receive is thirty-seven times the amount I put down as a premium – see table.

So, if the market stays reasonably steady I do not make any profit, losing all the premium I paid to buy the right to sell at 190. That is OK because this is a hedge against other positions, i.e. if the stock market and the economy are doing well then my long share portfolios are doing fine.

(Please note that many other people speculate with options going all in on one side of a bet or the other. I have off-setting positions, so a swings and roundabouts approach is taken.)

But if the Dow falls below 188.67 I will probably be losing on my long-only share portfolio in that period. But I can make a multiple of the amount I paid for the option.

A couple of additional points:

- Of course, to hedge my underlying I have bought many more put options on the Dow than one.

- I can sell my right to other investors at any point between now and the third Friday in Septmber.

Why options rather than other ways of shorting?

With options my downside is limited to the option premium I’ve paid. I cannot lose more than $133 per put option. The counterparty cannot come to me at a later date and ask me for more money unlike with other types of derivative positions.

Take futures (similarly for contracts for difference): if I had a futures position to sell at 252 and the Dow fell to 19,000, or 190 on the future, I would win 62 points per contract at $100 each point ($6,200). To take this position in the first place I might have to put down, say, ten points of “margin”, i.e. $1,000 [see Chapter 9 for futures].

But what if things had gone the other way and the Dow rose to 30,000, or 300 on the future? Then I would be obliged to sell to my counterparty at 252 but have to buy at 300. Thus, I have lost 48 points. I originally put down only ten points of margin but now I have come up with another 48 points, or $4,800, 4.8 times what I originally committed.

Indeed, as the market was moving against me the counterparty clearing house would have insisted that I keep sending money to them – far more than the $1,000 I originally put down. I have an open-ended commitment with futures that I do not have with buying options. I’ll sleep much better knowing the maximum I can lose on the options position is what I’ve already paid in premiums.

There is, however, one advantage of futures - you do not have to pay a premium to have the right to sell. But these are dangerous instruments unless you really know what you are doing.

Other possibilities for shorting the Dow include exchange traded funds, but these are less geared than the options and so require more money to hedge my underlying.

Useful websites

| www.advfn.com | ADVFN |

| www.bloomberg.com | Bloomberg |

| www.cboe.com | CBOE |

| www.derivatives.euronext.com/en | Euronext derivatives |

| www.ft.com | Financial Times |

| www.fow.com | Futures & Options World |

| www.theice.com/futures-europe | ICE Futures Europe |

| www.globalinvestorgroup.com | Global Investor Group |

| www.money.cnn.com | CNNMoney |

| www.reuters.com | Reuters |

| www.wsj.com | The Wall Street Journal |

_______________

1 Expiry of options is on the third Friday of the expiry month.

2 For this exercise we will assume that the option is held to expiry and not traded before then. However, in many cases this option will be sold on to another trader long before the expiry date approaches, at a profit or a loss.

3 £670 is the intrinsic value at expiry: (2567p − 2500p) × 1,000 = £670.

4 This is somewhat simplified. In reality, Joe would have to provide a margin of cash or shares to reassure the clearing house that he could pay up if the market moved against him. So it could be that all of the premium received would be tied up in the margin held by the clearing house (the role of a clearing house is explained in the next chapter).