2

Look for clues

The people hacker

Jenny Radcliffe, social engineer, human factor security expert, people hacker. Jenny uses her expertise in non-verbal communication, deception and persuasion techniques for ethical white hat hacking to help secure client sites and protect them from malicious attacks. She was part of the special operations unit for the successful Channel 4 series ‘Hunted’.

‘I’m a hacker, but I’m not the stereotypical hacker in a hoodie behind a computer, I’m a security consultant and I work with psychology, as a “people hacker”. My job involves physical infiltration, when organisations or high net worth individuals give me permission to try and bypass their security measures and gain access to their premises.

These are necessary exercises to expose security flaws and educate clients, so that they can fix the gaps and the bad guys can’t come along and do the same thing as me. So, I’m an ethical hacker; consider me a burglar for good.

One client asked if I could try and gain access to his office inside a building on what he considered to be a secure site. He said, “You’ll never get in. We’ve just spent £2m on the perimeter defences, we’ve got fences, alarms and guards. The only way you’ll get in is if someone leaves the door open for you, and that will never happen.”

Accessing any site requires detailed planning. I use open-source intelligence techniques (OSINT) to research the industry, the organisation, the building and the people. I’m looking to find any levers or triggers that they will respond to, that might be exploited. This is often something that fits in with their values and beliefs or with the way they operate and conduct their business.

My research showed that this company was traditional and hierarchical, operating in an industry with multiple safety considerations. It was important people followed rules and this was a key part of their company culture. The management were “god” and people did what they were told. So that’s what I worked with.

To breach the fence, we used a pellet gun to shoot a crack in a car windscreen and then posed as a car maintenance and repair firm, as per the staff benefit package. This convinced their security staff who let us through the fence, but we still needed to get into the building. My “windscreen repair” colleagues left and I hid and waited.

I had prepared a piece of paper, with “Please do not close this door. Thank you.” printed on it. I’d signed it with a vague signature, and printed “HR Dept” underneath. It looked official enough and I sellotaped it to the currently closed, external fire door.

After a while someone came out and paused as they saw the sign on the door. Then they obediently wedged open the door and left.

I waited, watching people leave, each happily leaving the door open as per the sign telling them to do so. After most people had left for the night, I walked through the door into the factory and found the client’s office. I took some pictures to prove access and left my calling card for him to find in the morning, and that was the infiltration complete.

If I had been a criminal, the consequences of this type of security breach would have been very serious.

They were only eight words, but used in the right place with the right person, it worked.

It wouldn’t have worked at every site; it might not have worked on a more casual company or in a rebellious culture where rules were not seen as so important. However, used in the right place with the right people, that piece of paper was able to open the door.

Eight words, but if you know how a group of people operate, then sometimes that’s all you need. Psychology and culture do the rest.’

2.1 The secret to making persuasion easy

So we’ve learnt to aim high and we’ve learnt if we don’t ask, we don’t get. But that doesn’t mean if you ask you will always get. Sometimes persuasion can be really difficult. Sometimes it is beyond the other person’s control to grant your request – ‘I would love to help you, but my hands are tied’.

But there are always answers, if we look hard enough.

Over the years I’ve been teaching negotiation skills I’ve worked with many top negotiators. One colleague who was regularly involved in nine-figure deals in London’s financial Square Mile described his negotiations. ‘It’s strange’, he said, ‘I will go to the meeting, I’ll shake hands with the other person, we have a nice chat over a cup of coffee and then we sign the deal and then I leave. It’s not like a negotiation at all, it’s just a nice conversation’.

How come? Was he just such an amazing negotiator? Natural born? Or lucky?

No, none of those. It was just that he had done the preparation. That meeting was at the end of days, weeks or months of preparation.

If you want the conversation to go really smoothly, the secret is in the preparation. Do that research and you will find the clues you need to persuade.

What should you prepare? Lots! Almost every paragraph of this book is an item to cover in your preparation. Know the facts, know the figures – yours, theirs, the competitors, the benchmarks. Things won’t necessarily go in a straight line so scenario plan, know the what-if’s, anticipate the difficult questions, the push-backs, the offers and your responses to all. Do the thinking now, so you don’t have to do it later, under pressure, in the conversation.

The ABCD of research is Always Be Collecting Data and this is a good guideline to remember. Look for clues everywhere and you will find them and they will help you in your mission.

And prepare your mood. You probably find that when you’re in the right mood, you’re unstoppable, so what can you do beforehand to make sure you’re in that mood in the meeting? What mood does it need to be? Super-confident? Strong and robust? Quick-thinking and alert? Charming? Whatever it is you need for your conversation, do what you need to do to get in that state of mind and then the results will just follow.

Now I know some people can be afraid of these situations, but it doesn’t have to be like this. Even the toughest of conversations can seem like a nice chat if you prepare properly. You can enjoy them; you can even look forward to them.

And if you do, you will almost certainly get better results.

2.2 Clues in the context

In your research, you will find clues – clues everywhere; clues that can help you change their minds.

You will find clues in the context. We can learn a lot about someone from the context. Where do they work? Where do they live? Do they spend their time in the gym or the pub? Do they spend their money primarily in Harrods or at the Saturday car boot sale? If you’re meeting in a restaurant of their choice, are they taking you to the local McDonald’s or for some posh nosh in Mayfair?

In fact, some studies have shown that the location actually impacts personality profiling scores. For example, people tend to measure higher on extraversion in cafes, lower on neuroticism in places of worship and higher on conscientiousness in gyms.1

So, expect a different response accordingly. Expect a different response if you are meeting at a wedding or at an academic conference. Expect a different response if there is an economic crisis going on or a time of plenty.

It turns out that people make their decisions partly depending on the context – wow, who knew? Well, maybe you did, but did you know just how much it depended on context? And how you could, therefore, use it?

It can be really nuanced. Researchers put four bottles of French wine and four bottles of German wine on sale in the wine section of a supermarket: on days that French music played in the background, three times as much French wine was bought than German; on days German music played the figures were reversed. And when asked about their choice, 86 per cent of shoppers said specifically they were not influenced at all by the music.2

Context counts. You can learn much from it and you can strategise how you might persuade better.

Try speaking in a French accent, you never know.

2.3 Clues in their story

A few years ago, I had a sales meeting with a large law firm and I did some quick research on the person I was meeting. My usual strategy for a law firm is to play it straight – smart suit and tie, nice briefcase and polished shoes.

But five minutes on Facebook showed me this person happened to be the lead singer of a thrash metal band. I took a different approach to normal.

Human beings are just human beings. So if you’re trying to persuade someone, bear that humanity in mind.

One of the most successful negotiations in recent times was the Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement which ended decades of civil war in the region. The process was chaired by Senator George Mitchell and anyone who wanted to get something into the final agreement would, ultimately, have to persuade him.

In the three years of the negotiations, Mitchell married, had a baby miscarried, another one born and his brother died.3 So many emotional moments of such intensity, these were bound to be on his mind, no matter how professional or heroic he tried to be. Taking this into consideration could make or break your request.

Understand their perspective

But it is not only such high stakes negotiations or such life-and-death events. In any situation one thing you can guarantee is that the other person will see the situation very differently to how you see it. And, typically, we have our rationale, our evidence to back that up and we think ‘It’s obvious, isn’t it?’

But they have a very different perspective, they have a very different rationale, they have their own evidence to back that up and they think ‘That’s obvious, isn’t it?’

And what we do is go back to our rationale, louder. And it doesn’t work.

And this is why our world is full of irrational people making crazy choices. Actually, they’re not irrational, it’s just they have a different rationale to ours.

What we need to do, instead, is take the time to step into their shoes, understand their perspective and then put our outcome in terms of their rationale. That’s the only way that will work. Anything else and they will say ‘Yeah, but you don’t get it’.

One of us

If we know someone’s story, we know who they are and this is crucial if we want to change their mind. If they see us as different to who they are, if we are a ‘Them’ to their ‘Us’, it will be very difficult to persuade.

Human beings are very tribal – for good reason: for millions of years the animals we feared the most have been other human beings. So, we have deep wiring to distinguish between ‘Us’ (safe, can trust) and ‘Them’ (definitely not safe, definitely can’t trust).

Mark Levine and his colleagues at Lancaster University conducted a great study where they invited a group of Manchester United fans in to write an essay (a bit ambitious, I thought) about why they were a Manchester United fan.4 It was then set up that as they left the building, they saw a runner slip and obviously hurt themselves. If that runner wore a Manchester United shirt, 92 per cent of people went over to help; if they wore a Liverpool shirt, only 30 per cent helped.

The really interesting part of the experiment was the second phase where they invited a similar group of United fans to come in and write an essay, but this time the essay was about why they were a football fan. Now, 80 per cent helped the Liverpool fan. It was no longer ‘I’m a Manchester United fan, they’re a Liverpool fan’, it was ‘I’m a football fan, they’re a football fan’.

We are all plural. I’m a man, a middle-aged man, yes Stale Pale Male! I’m English, I’m half-Irish, I’m Essex Man, a West Ham fan, a football fan. I’m an author, I’m a trainer, I’m an occasional meditator, I’m an avid reader, I’m an ex-trapeze artist, I’m a scuba diver. I’ve travelled to 80 countries; the likelihood is I’ve visited your country and if I did, I almost certainly loved your country. I’m a son, I’m a brother, I’m a human being, and so much more. . . we have a quasi-infinite range of identities and they all have different perspectives and attributes and at any given point in the day I might be in one and at the next moment I will be in another.

This is good news. It gives us the opportunity to find that overlap with the other person, through knowing their story. And once you have done this, you can build a deeper connection with them and work with them so much more effectively.

8 WAYS TO BECOME ‘ONE OF US’

- 1.You work in the same field.

- 2.You live in the same town.

- 3.You have the same interests or hobbies.

- 4.You have had a similar experience in the past.

- 5.You are from the same background.

- 6.You are the same age.

- 7.You are the same gender.

- 8.You live on the same planet.

2.4 Clues in their personality

If you want to change their mind it helps, of course, if you know how they think – and there are all kinds of personality tools that can help with this.

Some like Myers–Briggs and DISC are used a lot in the office; Belbin is used for the team context; and others (‘Which kind of squirrel are you?’) don’t seem to have much use at all.

One that is very relevant to changing minds was developed by Doctors Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann and is known as the Thomas–Kilmann Instrument which categorises people according to how they manage conflict. Unfortunately, Thomas and Kilmann fell out when deciding on the name. . . ok, no they didn’t, just my little joke.

They identified five different types of people.

- 1.Competing

The competer likes to fight, looks for a fight. They want to win and they want you to lose.

Thomas:I insist we call this the Thomas–Kilmann Instrument.

- 2.Accommodating

These are the ‘nice’ people, too nice, people who lose out.

Thomas: Let’s call it the Kilmann–Thomas Instrument.

Kilmann: Oh no! We’ll call it the Thomas–Kilmann Instrument, that’s much better.

- 3.Avoiding

These are the scaredy-cats, the people who don’t like conflict at all.

Thomas: What shall we call our fantastic new instrument?

Kilmann: Erm, good question, can we talk about it later?

- 4.Compromising

The ‘split the difference’ types who think compromise is win–win (when in actual fact it is lose–lose; neither side fully gets what they want).

Thomas: Shall we call it Thomas–Kilmann or Kilmann–Thomas?

Kilmann: How about Kiltho–Masmann?

- 5.Collaborative

The sensible, intelligent, successful type, usually good-looking, who work together to find a solution that suits everyone.

Thomas: We can call this model the Thomas–Kilmann Instrument. . .

Kilmann: . . . and we’ll call the next one the Kilmann–Thomas Instrument.

(High fives)

Let’s hope Kilmann especially isn’t the competitive type because he might sue me for defamation of character, but I am confident he is the sensible, intelligent, successful, good-looking, collaborative type so I should be ok.

Joking apart, the TKI can be a really useful exercise before any negotiation or persuasion situation. It will help predict the other person’s likely response and which approach would be your best option.

Each of the types has got their place but, as you’ve probably guessed already, this book suggests the collaborative approach will be most successful in the large majority of cases.

The OCEAN Big Five

In recent years, the scientific world has coalesced around the OCEAN Big Five tool as the profiling instrument of choice. I suspect there is an element of self-fulfilling prophecy here – it seemed to be studied more than the others, which gave it more credibility, and so it was studied more, which gave it yet more credibility – and so on.

Whatever its history, the net result is that it is the tool with the most amount of credible research to back it up and therefore the most rigorous scientific support. This model also identifies five types of people, but these types are applicable to a much wider context than just conflict.

Once you know what type they are, you can tailor your message accordingly. In 2012, Hirsh, Kang and Bodenhausen published a study that showed how you might do this.5 Their experiment presented five different advertisements for a fictitious ‘XPhone’, each targeting one of the traits. Respondents were much more likely to judge the advert effective if it matched their dominant personality style.

These are the Big Five personality types, their characteristics and the XPhone advert most effective.

- 1. Openness

Openness to new ideas: those who score high on this dimension are typically creative, curious, tolerant, politically liberal; a low score on this scale correlates with pragmatic, down-to-earth, politically conservative.

‘With the new XPhone, you’ll have access to information like never before, so your mind stays active and inspired. . . ’

- 2. Conscientiousness

People high on this score are typically organised, focused on the goal and work hard; those low on this score are often more spontaneous and easy-going.

‘With the new XPhone, you’ll never miss an important message, simplifying your work life. . . ’

- 3. Extraversion

As the name suggests, people high on this score are sociable, friendly and often loud; those who score low are more reserved, serious and likely to prefer time on their own.

‘With the new XPhone, you’ll always be where the excitement is. . . ’

- 4. Agreeableness

Friendly, trusting, co-operative people score highly on this dimension; assertive, self-orientated, people who disagree a lot with others score low.

‘With the new XPhone, you’ll have access to your loved ones like never before. . . ’

- 5. Neuroticism

High scores here suggest an anxious, self-conscious worrier; low scores suggest a calm, self-confident and stable type.

‘Designed to keep you safe and sound, the XPhone helps reduce the anxiety and uncertainty of modern life. . . ’

Top tip

Don’t depend too heavily on the label. Just because someone is normally, say, extraverted doesn’t mean that they can’t enjoy time by themselves.

Use the right nudge with the right person

Patrick Fagan, behavioural scientist, visiting lecturer at three London universities, the author of ‘Hooked: Why cute sells. . . and other marketing magic that we just can’t resist’ (Pearson). Previously Lead Psychologist at Cambridge Analytica, he is currently Chief Scientific Officer at behavioural science consultancy Capuchin.

‘I’m a behavioural scientist and my job is to use psychology to influence people in the real world.

For example, I’ve recently completed a study where we used targeted nudges to increase the likelihood that people would save a phone number for a suicide prevention helpline into their phones.

In the first phase we had nearly 500 people complete an online survey, starting with a questionnaire that enabled us to psychologically profile them with respect to various demographic factors like the OCEAN Big Five tool, their gender and their age. It also profiled them with respect to their persuasion profile, using Cialdini’s six influencing principles. Then at the end of the questionnaire, there was a request to save a crisis line number into their phone.

Now each group had a slightly different message. The first group had a very neutral message but the second one conformed to Cialdini’s “Authority” concept (that people are more likely to be influenced by the trappings of authority) and the third to his idea of “Social Proof” (that people are more likely to be influenced if others are doing the same). For the authority nudge, we told them that experts say it works and gave them statistics to back it up, using high-credibility language. For the social proof nudge, the message stressed how other people are using the number, that it was a popular thing to do and so on.

And then we measured how many people saved the number to their phone. And what we found out was that these nudges worked. Both the authority and the social proof nudges increased the likelihood of saving the number by about 14 per cent.

But when we looked deeper and saw how the nudges worked with specific personality types, we got even better results. For example, women who scored highly for being conscientious were especially influenced by the social proof message. In fact, they were 40 per cent more likely to save the number compared to the same nudge used on other people.

So we followed this up with a second phase, where we specifically allocated a social proof message to women who scored highly on conscientiousness and randomly split everyone else to either the same social proof nudge or to no nudge at all.

From our control group, random population with no nudge, 14 per cent saved the number into their phones. From the random population with the nudge, 29 per cent of people saved the number, more than double. But a full 50 per cent of the conscientious women receiving the nudge saved the number.

So, these nudges work but they work even more effectively if we use the right nudge with the right person.’

2.5 Clues in the wider picture

If we want to understand the other person’s perspective, we need to understand the world in which they live. This world will involve many people: their family, their friends, their boss, their boss’s granny’s dog and so on. Ok, the boss’s granny’s dog doesn’t officially count as people, even if it thinks it does, but you understand my point.

- ■If you want to persuade your child to go to the extra homework classes, it might improve your chances of success if you ring up the parents of their best friend first and check if they are going too.

- ■If you are trying to persuade your neighbour to trim their tree but they are slow in getting round to it, a friendly letter from the local council saying the bye-laws allow you to trim it yourself (with you suggesting a date you’re free), might be the thing that nudges their elbow.

So widen out the picture and answer the questions: ‘Who else is involved?’, ‘Who else can be involved?’ and ‘Who else do you need to get involved?’.

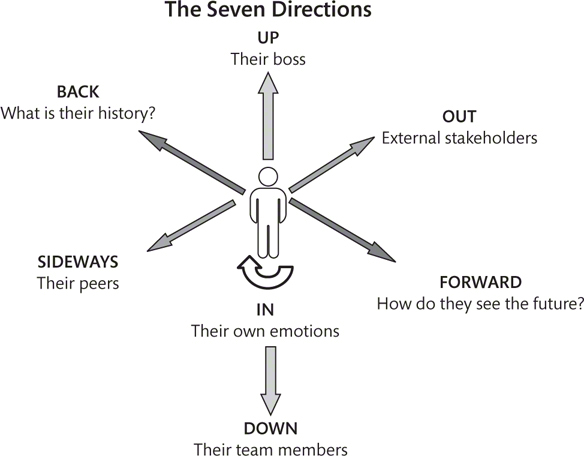

Let’s put this in a corporate context and we can use the model developed by Bourne and Walker,6 a model they called The Seven Directions, to identify key stakeholders:

Description

The diagram shows the processes of evaporation, condensation, evapotranspiration, water storage in ice and snow, and precipitation. A large body of water …

For you to understand the other person’s perspective, you need to know what’s going on with their boss, with their team members, with their peers and so on. And the more you know this, the more successfully you will persuade.

You can apply your own variation of this model even outside of work. Take a sheet of paper and draw on it everyone involved. You don’t have to be a great artist, I can’t even draw stick-people and it still works for me, but the visual mapping can provide a deep understanding of the situation. Somewhere on that map you will see someone (or someone’s dog) that is the critical person (or dog). And that’s how you will get your answer.

Top tip

Use as much visual richness as you can. Drawings, different colours, different types of lines or shapes can all carry extra information and bring a better understanding of the situation.

When Yanis Varoufakis became the Greek Finance Minister in the middle of his country’s debt crisis, his job was to persuade the famous Troika (the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the IMF) to buy into his plans for re-structuring the debt. But for this he needed to get more support from the political leaders of Britain, France and Germany.

Hardest of those to persuade would be the British government, famous for their love of austerity. If they were putting their own country through such tough measures, it was a slim chance they would allow any other country to get off lightly.

But Varoufakis had an unlikely ally. Three years earlier at an event in Australia he had met Norman Lamont, a grandee of the Conservative party and an ex-finance minister himself, and they had become very good friends. A quick call to Lamont and then a call from Lamont to George Osborne, the British Finance Minister, and the meeting was a surprising success.

And not a dog to be seen.

Understand the power dynamics through visual mapping

Dr Lynda Bourne, stakeholder engagement expert, lecturer at Monash University and Director of Professional Development at Mosaic Project Services. She is a recognised international authority on stakeholder management and visualisation technologies, publishing papers in many academic and professional journals on the topic.

‘I advised a global port management company who built new container ports and updated existing facilities in partnership with other organisations around the world. The work in each location was very similar, but for success the company really needed to understand the nature of the local stakeholder relationships and these would vary hugely.

Each specific location would have its own complex web of organisations including port management authorities, national government agencies, other shipping lines and operators and even local populations, and the attitudes and relative importance of each needed to be understood. And, of course, each partner organisation would have very different reporting structures, very different decision-making processes, very different national cultures – all of which needed to be understood thoroughly if the partnership were to be successful.

So the approach they took was a detailed stakeholder identification process based on teams using the “directions”. Mapping this enabled them to get a solid grasp of the diverse power relationships and the communication processes needed to influence decisions and move each project forward.

The situation was made even more complex by the fact that the same organisation may be collaborating in one country and competing in another. In these instances, they used the analysis to help manage the relationship and communicate the information needed to work together but at the same time ensuring competitive information was withheld.

Using a disciplined and consistent process to the stakeholder analysis across all of the locations, they were able to achieve a better understanding of the stakeholder group at each port and the local power dynamics, and were therefore able to build more effective working relationships and more successful projects.’

2.6 Clues in the culture

In the globalised world of today, we can easily find ourselves trying to persuade someone from the other side of the planet; and if we want to do this, it helps if we understand their culture. Working with someone from Beijing is very different to working with someone from Paris, which is very different to working with someone from Mexico City and so on.

And if we get it wrong, it can be disrespectful and might break the whole deal. Many billions of dollars have been lost by organisations that did not take this factor seriously enough.

Clearly, there are too many cultures in the world to cover them all here, but it is worth your while learning some general principles.

7 WAYS TO WORK SUCCESSFULLY ACROSS CULTURES

- 1.Understand their culture as well as you can. Study it in every way possible.

- 2.Spend lots of time in their country.

- 3.If you don’t know it well, find someone who does.

- 4.Compare your culture with theirs and note the differences.

- 5.Discuss any differences with the other person. Celebrate them.

- 6.Expect miscommunication and allow for it.

- 7.Meet face-to-face in your country or theirs if you can.

Of course, cultural differences aren’t just national, they arise across regions within countries too – Milanese have a different mind-set to Napoletanos; New Yorkers are different to Texans; highlanders to lowlanders; coastal people to continental.

And it’s not even just geographical: different industries will have different cultures, different organisations within an industry, different departments within an organisation, different teams within the department. There are cultural differences across age, gender, race, schooling, income strata, social tribe.

And then, for all your learning of their culture, remember that the individual is not their culture. So always treat everyone as unique. Use the cultural guidelines as exactly that – a guideline; but be ready to learn that this individual is quite different to their group’s norm.

Ultimately, all interactions are cross-cultural; we are all in a culture with a population of one.

If you hold the pen, you have the advantage

David Landsman, former positions include British Ambassador to Greece, British Ambassador to Albania, Managing Director of Tata Ltd (Europe) and Director of UK India Business Council. An international negotiator and expert in corporate strategy and geopolitics, he is currently Chairman of Cerebra Global Strategy and Chairman of the British-Serbian Chamber of Commerce.

‘As a former diplomat who previously studied linguistics, I’ve always been interested in the role language plays in diplomacy, in its broadest sense. Knowing the other person’s language is of immense value. When I was posted abroad, I was almost always fortunate enough to have had the chance to learn the language before arriving, which without a doubt gave me an advantage over diplomatic colleagues who didn’t.

Of course, you can hire a translator, but they can never explain every detail of how it’s been said, the tone of voice or the implication. On the other hand, I’ve negotiated in the EU, NATO and the UN and I definitely don’t speak everyone’s language!

In the early 2000s, I was part of the European team negotiating with Iran on its nuclear programme. I had the advantage that the negotiation was in English, but it would definitely have been better if I had been able to understand Farsi too. As I recall, only one of our team did, whereas several Iranians understood English, which gave them many advantages: a few seconds’ extra thinking time while the interpreter explained; they could pick up nuances better; and they could even understand the asides when we were talking “privately” to each other.

Even better is to be a native speaker of the language the negotiation’s being conducted in – and today that’s usually English. I recall one negotiation in the (then) G8 taking place in London under a British Presidency. We were trying to find a way of bridging a serious underlying difference about a recent development with North Korea and its nuclear weapons.

Some wanted to take a stronger line than others: some wanted to express “deep concern”, others didn’t want to go beyond “concern”. We batted this about for a bit with no progress. Then I suggested we try an alternative: how about “profound”? Nods all round.

If you hold the pen, you have the advantage.

“Language” can go beyond whether you speak French or Farsi. It’s important to think holistically about what’s being said and when, by whom, as well as what’s not said.

I was in Libya negotiating with senior members of the Gaddafi regime following his decision to abandon his chemical and nuclear weapons programmes. This was a difficult decision for Libya and the negotiations were tense.

The two lead Libyan negotiators were chalk and cheese, though both were very senior and had strong links to the Leader. One dominated the talks, spoke only in Arabic, often loudly and aggressively, and did a pretty good job of tiring out some of our team. His colleague, however, kept silent for much of the long negotiating sessions, although he spoke excellent English and no doubt picked up all the nuance. In the end, it was he who summed up calmly in a few words. No doubt who was boss.

Negotiators ideally speak the language(s) of the negotiation. If they’re lucky, they hold the pen. But even if neither of these is possible, paying active attention to “language” in its broadest sense will certainly help.’

2.7 Clues in the channel

What’s your favourite medium? Not who’s your favourite psychic, but how do you like to communicate?

Everyone has their favourite channel, and if you want to change the other person’s mind it is worth thinking about which channel will be best. A large part of the answer will be the channel they like best, whether that’s face-to-face or TikTok or messenger pigeon.

We can learn a lot about them from their preference. If it’s face-to-face, do they want a formal meeting at the office or would they rather a quick chat at the local coffee shop or the taster menu at a Michelin-starred restaurant? If it’s video-conference, do they have the camera on or off? Do they prefer the phone or the latest still-in-exclusive-invite-only-mode platform?

We can learn about them from their communication style too. Many years ago, I was running two different projects with two different friends, both called Alex. One was hard-nosed investment banker Alex and the other was soft, fluffy, hippy Alex. Hard-nosed investment banker Alex would ring and the call would never last more than three minutes. It would be bish-bash-bosh and bye, no time for how are you. Soft, fluffy, hippy Alex would call and it would take an hour and a half whatever it is we were talking about. Before we talked about anything to do with the project, he wanted to know how I was feeling and then he would tell me how he was feeling and then he wanted to know how I was feeling about how he was feeling and so on.

I’m exaggerating, of course, and both Alex’s were very good friends and both projects were successful projects, but I did have to bear in mind each other’s communication style if I wanted to get my outcome.

Even if it’s good old vanilla email there’s a lot we can work with. Some people write long emails, some write one-word grunts, some don’t even respond at all. Some are bullet-pointed, some start with asking about your weekend and others have lots of emojis and fluffy bunny rabbits.

It’s all useful information about who they are and how you can best communicate with them to get your outcome.

In summary

If you want the conversation to go well, you can’t beat doing the preparation. It’s the same with everything – the results you get are a function of how well you prepare. And if you do that research, you will find clues everywhere to know how to persuade them.

- ■Understand their perspective

One thing you can guarantee is they will see it differently to how you see it. You have to put your message or your outcome in terms of how they see it. Otherwise, it just won’t get through.

- ■Become ‘one of us’

Human beings are tribal animals and you want to show that you and they are of the same tribe. This is not to fake it; you should be able to find a genuine overlap between who they are as a person and yourself. Once you’ve done this, they will be much more open to your idea.

- ■Know their personality type

Everybody is different but personality profiling can be a quick way to understanding how someone thinks. If you know how they think, you can use this to predict how they are likely to respond to your request and how you might change your approach for greater success.

- ■Understand who else is involved

It is never just you and that one other person, there are always other people involved – even if you aren’t aware of who they are. But if you can map out everyone involved and identify their drivers, it can help you navigate a route through to success.

- ■Understand their culture

Ultimately, everyone is in a culture of one, but understanding the person’s broader culture in which they live and work can give clues as to how they might respond.

- ■Which channel should you use?

Typically, we default to our favourite, whether that’s email, phone or the rooftop restaurant with great views across the city. You might, however, want to choose their favourite channel instead. Either way, knowing their choice of channel and how they use it can give interesting pointers to how you can influence them.

So, look for clues everywhere. You have to listen for clues too, but we’ll cover that in the next chapter.