CAREERS IN THE INDUSTRY ADVERTISING, DESIGN, STOCK PHOTOGRAPHY, MAGAZINES

When we see a photograph in a magazine, on the web, or hanging on a gallery wall, we naturally assume that we are looking at the work of a photographer. In fact, we are actually seeing the collaborative efforts of a multitude of players behind the scenes: art directors, web designers, lab technicians, artist representatives, retouchers, printers, studio managers, assistants, and editors.

Some artists—painters, sculptors, and writers for example—can work in relative isolation, but photographers require a vast infrastructure of unseen, and unsung, collaborators to support their work, from camera manufacturers to lithographers. Photography is an art form that is also an industry.

Years ago I had a very talented and dedicated student. I knew he’d be successful as he started his career as a freelance photographer and I was right. Within a year after graduation he was shooting feature stories for magazines like Fortune and Forbes.

The only problem was that he hated it. The thing he hated most about the job was the constant traveling, which is typically one of the things that draws young people into the profession. He craved the day-to-day stability that comes from a regular workplace.

He gave up working as a freelance shooter and opened one of the best custom darkrooms on the East Coast. He now prints major museum exhibitions and collaborates with some of the most famous artists in the world. The hours are long, and the attention to detail is exacting. It suits him perfectly and he is very successful.

Virtually every person you meet in the greater photographic industry, whether they are web designers, photo agents, or editors, started their career by studying photography with the intention of becoming a shooter. They never lost their love for photography, they just found another niche that was more rewarding, and ultimately a career that would make them happier.

JENNIFER MILLER: PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR CONDÉ NAST TRAVELER

In essence, photo editing is curating and distilling the appropriate images for a particular purpose from the vast sea of possible choices.

Photo editors are connoisseurs of photography and photo editing is (or can be) one of the most rewarding and collaborative professions in all of photography. Photo editors rely on an encyclopedic knowledge of images and photographers in order to find and supply appropriate existing or historical photographs, and assign projects to contemporary photographers to create new images.

The title of photo editor actually encompasses a wide variety of jobs; it might mean finding photographs to illustrate a textbook (photo-research), or evaluating images from contributing photographers at a stock photo agency. In fact, because the title is so broad and can carry such a variety of responsibilities, it can open up a variety of different employment options over the course of one’s career. It’s not unusual for a young photo editor to start at a news service, move to a magazine, then eventually become an art buyer at an ad agency, or end up as the owner of a stock photography agency.

That said, the term is traditionally used to describe someone at a magazine who has the responsibility to fill the magazine with photographs every month, but with the growth of e-magazines and websites even that job description fails to encompass the role of the contemporary photo editor.

Jennifer Miller has always been one of my favorite photo editors. She loves photography and photographers. She understands the problems we face and she values our contributions.

Interview

MJ: So let’s just start at the beginning. How did you get started as a photo editor?

JM: I started as an intern with working on books with Marvin Heiferman and Carole Kismaric. I had no idea who they were at the time but I quickly learned that they were these big-time art photography curators/writers/book publishers who knew every important photographer humanly possible. That internship experience was really pivotal to my career. Working with them really taught me how to think about photography conceptually.

Later they recommended me for a job at Aperture. At Aperture my job was to photo-copy and physically paste photos into layouts; this was all before digital layouts obviously. Then I applied for a job at the Magnum Photo Agency, which I got, again, thanks to recommendations from Marvin and Carole.

My job at Magnum was working as a picture researcher. I’d take calls from photo editors at magazines who were working on a story, and then my job was to dig through these crazy, incredible archives for the appropriate images. I learned a lot from that job because I’d get such a wide array of requests; sometimes they were very specific—“I need a horse in a field,” that kind of thing—but other searches would be less literal and I could be a lot more creative with my interpretation of images that could fulfill the request.

Then eventually, I got a call from the photo editor at George magazine [a great, innovative, but short-lived magazine that was started by John F. Kennedy Jr. that focused on politics and popular culture]. She needed an assistant; I took the job and when she moved on I became the photo editor at George, so that was my first job as the head photo editor.

MJ: Over the course of writing this book it’s been incredible to see how important internships are—or can be—to the entire arc of your career.

Katey Cunningham

As stories and layouts are completed the finished pages, not including ad pages, are posted on a wall in the magazine’s offices.

JM: Yes, it is. It all started with working for Marvin and Carole. When George folded I went on to become the Director of Photography at Jane magazine.

Eventually Jane folded as well. I kinda kicked around for a couple of years at various magazines and as a freelance photo editor, then I ended up at Martha Stewart for a few years, and finally here at Condé Nast Traveler.

MJ: Tell me about your day-to-day job in your role as the Director of Photography for Condé Nast Traveler or about photo editing in general.

JM: It’s very different depending on the magazine you are working for. CN Traveler might be one of the best places I’ve worked because I have a lot of creative freedom; at other magazines the photo editor position can be very focused on production and organization.

At the moment my magazine is in the middle of a big transition, which offers a lot of creative freedom for me. I’ll spend time talking to the editors about stories they are working and ascertain what kind of photographs will be right for the story: Is it a straight travel story, do we want something more artful, more painterly, something looser?

Then I think about which photographers might be right for each story and who is available to shoot for us. Once I’ve established that I’ll confer with my staff to figure out the production and logistics of the story. How do we get our people there? The dates, the times, those kinds of things.

Then I’ll pull photo references, which is really fun. Because Traveler has a whole new staff, we are reinventing many aspects of the magazine, like the overall visual language for the cover, so I’m pulling a lot of vintage photographers like Moholy Nagy, Martin Munkácsi, and Hans Mauli as references for what our covers could become. That’s very exciting for me, because at other magazines, with an established staff and aesthetic, you have to stick to the established “look” of the magazine so you end up using the same photographers over and over for both the cover and inside the magazine

MJ: I always did very well approaching magazines that were just starting or in the throes of a redesign. It’s very difficult to break into an established magazine. In fact my first big story was actually for Condé Nast Traveler. I had heard that Condé Nast was launching a travel magazine and before they published the first issue I pitched them a story about a family of ski racers/coaches that I had trained with in France. It was one of my first big features and a major turning point for my career.

JM: Exactly, because they need an influx of fresh ideas and vision, and there’s also an element of panic because everyone is thinking, “Oh my God, we have all these stories to do,” so sometimes you are a little more willing to take a risk. Later on when the magazine establishes a brand it can become very rigid and people become afraid to break out of it.

I think this magazine in particular got a little stuck in an aesthetic of 1990s “spectacle” photography: Every story became a variation of “a celebrity, on a boat in the Amazon wearing a red couture gown,” or “here’s a model and she’s hanging off a gargoyle on the side of the Chrysler building wearing a $200,000 dress.” It was successful for a long time but it’s gotten outdated.

MJ: It’s funny because when I was hired by Traveler back in the day Harold Evans was the Editor in Chief and his motto for the magazine was “Truth in travel” so he encouraged me to think like an investigative journalist.

I did a story on skiing in Las Lenas, Argentina, a fantastic ski resort, but I discovered that the employees were living like migrant workers, working 20 hours a day, sleeping in barracks, that kind of thing. So I did the story I was sent to do, which was a lush story on a luxury ski resort, and then I also did an exposé on the worker conditions. Of course, the second story never saw the light of day so I never tried anything like that again! I learned quickly to come back with the story the editor had in their fantasy.

By and large, the magazine/media world is an idealized world, whether you are talking about fashion models with perfect skin or traveling to a country where everyone is beautiful and perfectly styled. I think that even in hard news magazines there is a certain gloss that is applied to every story.

JM: Right, I think that even in magazines that do hardcore photojournalism there is a certain curation that happens to every shoot. The edit—the final selection of images—is a very powerful thing. Traveler is not a news magazine and ultimately we are selling a dream of sorts, but I definitely push the boundaries at times. I can give a nod to political or economic realities that exist in a place. Nobody travels in a vacuum; otherwise you might as well stay at home.

MJ: As a person who hires photographers, what do you want to see on their website, or at a portfolio review?

JM: Of course the first thing is a strong photographic eye. But I will often meet with photographers that I like, but aren’t quite right for the magazine, because you never know when a unique story will come in, or an opportunity will present itself to open up the magazine’s vision.

But for a travel magazine the ideal photographer at the moment is someone who shoots in a loose-authentic way, and can shoot landscapes, portraits, interiors, and food. Food in particular is tricky; there are lots of photographers I’d like to use, but because their food skills aren’t up to snuff I can’t use them.

MJ: I always hated shooting food, but for almost four years I shot the restaurant column for New York magazine twice a month. It’s so persnickety, you have to be very detail oriented.

JM: Oh, tell me about it! When I was at Martha Stewart the level of perfection that was expected in a food shoot was insane! It’s a little easier here because we are shooting the food in an environmental context, but it still has to look like its available light even when it isn’t, and it has to look delicious.

I’ve had a few stories recently where there was no food involved so I was able to hire photographers with more of a fine-art background because all I needed were portraits and interiors.

In general, what I’m looking for is an overall aesthetic tone, and I’ll always edge more towards fine artists when I can. Because Traveler is in the middle of reinventing itself I’m trying to define a new language for the magazine,-which for now seems to be a “polished documentary” approach. It feels loose and real, but it’s still beautiful and intriguing.

MJ: Because of the demand for online content and tablet versions of the magazine, how important is a photographer’s “motion” or video portfolio to you?

JM: That might be an area where we are playing catch up. The online, tablet, and print versions of the magazine aren’t really integrated yet. At Martha Stewart it was more integrated and we did more with motion, but because video/multimedia stories add so much extra expense to a shoot—more days, equipment, crew, etc.—it becomes difficult because we don’t want the video story to compromise the print story.

At Martha Stewart we did video production, but it was all in the studio. Because everything at Traveler is shot on location it’s a much bigger budget issue. We are looking to integrate video more and more over the next year or so but our emphasis now is still on print.

MJ: I teach a whole class on that now. I think photography is at a point now with motion/video that is like where we were 15 years ago with digital; you either learn it or you get left in the dust. Virtually every job I’ve had in the last year has had a video component.

JM: To a certain extent you’re probably right, but I recently had a conversation with someone else in the business about which magazines will do better in a print environment versus digital. I think that certain magazine categories—pop culture, news, tech etc.—are better suited to digital, while luxury magazines are better served in print form.

MJ: As I think about it you’re probably right. News magazines in digital form can offer unlimited real estate to photographers and tech magazines like Wired can include hyperlinks or demonstration videos in stories, but the luxury magazines are so much about lifestyle and fantasy …

JM: Exactly, but you are right about the ability to run bigger stories. We do stories in the magazine and we only have space for ten pictures, but we can run a 20- picture slide show on the website.

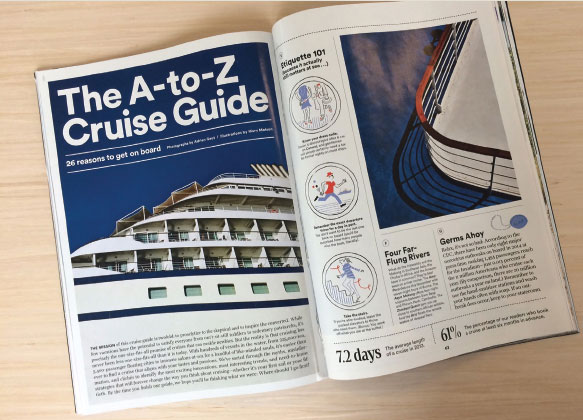

These images from Adrian Gaut’s portfolio and website convinced Jennifer that he could bring a fresh perspective to one of the magazine’s recurring stories.

© Adrian Gaut

Online content also offers opportunities to less established photographers. We might have a young photographer who has done a great story on a village in India; maybe the pictures are too gritty for the print magazine, but if the photos are amazing and if we love the story we’ll run them online.

For me, as a photography director, that’s an exciting new possibility.

MJ: You know, I’ve always thought that the two best jobs in photo editing were Rolling Stone and Condé Nast Traveler.

JM: Really? Why?

MJ: Well, yeah, because … Rolling Stone has the greatest variety of stories, everything from celebrity shoots, to investigative journalism, but Condé Nast Traveler, at least when I was working for them, always gave me a big enough budget to do the story properly. Not that I was personally getting a lot of money, but if I thought I needed something to do a story right, like renting a helicopter, or hiring additional crew, I always knew I could just do it.

JM: At a certain point the photographer and the photo editor should both know what is really needed to get the shot they need. If you need to shoot something large and from above, and you need a cherry picker then I’ll do what I can to get that expense approved. The photographer just has to be honest about what he/she needs and the photo editor should be in agreement. It just makes sense, but it needs to be discussed beforehand.

MJ: And that actually brings up another point that I think is surprising to young photographers: Photo editors are your friends.

JM: Yes, of course, and they should be! But why do you say that?

MJ: Students and photographers who are starting out are often negotiating with clients who don’t know much about photography and are trying to get a job done as cheaply as possible. Consequently, they often view photo editors in that same kind of adversarial light when they first start dealing with magazines.

But photo editors are different, they know what’s involved in doing a great shoot, they are fans of photography, and they know that the magazines don’t pay what photographers are worth, so photo editors—the good ones—fight to get as much money as they can for the photographer and fight to get the best pictures published.

JM: Exactly, and if a photographer is really good, reliable, and great to work with, that’s the kind of person I want to establish a long-term relationship with. I want the photographer to be happy, so within reason I’ll do everything I can to try to get them the budget and access they need. My goal is to have both the photographer and the magazine have a good experience and maybe even create something above and beyond.

MJ: And that’s why I love photo editors!

My first big shoot for Fortune I was on the road for seven days, but I traveled to at least ten cities in those seven days. I ate almost every meal on a plane, or at a hot-dog stand. When I submitted my invoice to my photo editor he noticed that I had billed less than $100 dollars total in meals for the entire trip. He called me and told me that I needed to send another invoice with an additional $500 dollars for meals. It was so great for him to do that; I was just starting out and the extra $500 bucks was a lot of money to me.

JM: That’s pretty common with young photographers; they want the job so badly that they’ll send me an estimate that is so low it isn’t realistic. In that case I’ll do a little education and get them to send a new estimate that’s closer to the actual money that we have budgeted for the shoot. Another thing is that when the industry switched to digital, photographers lost the markup on film and processing that was a profit center while incurring additional overhead in computers and equipment. Our stories include a provision for digital capture (essentially an equipment rental expense) and a lot of young photographers aren’t aware that we expect digital capture/equipment rental as an item in their invoice so I’ll tell them to include it.

I rely on my pool of photographers, so I want to be able to call on them in the future and have them be happy to work for us.

MJ: Is there any particular photographer or story that you can think of off the top of your head that would be a good example for us to talk about why you chose the photographer and how that choice influenced the end result?

The finished cruise story

Adrian Gaut

JM: Yes. Every year the magazine has to do a cruise package and for the past ten years the cover for the cruise issue has been something along the lines of: “Woman standing on a cruise ship looking off into the sunset.”

We were trying to find a way to modernize the cover for that issue and there’s this terrific photographer Adrian Gaut; he’s very versatile, he can shoot interiors and still lives. His work is very graphic, very architectural, and he has incredible taste, which is very important for our magazine. And he is chill, so he’s very easy to work with.

I sent him to shoot a cruise ship in Cabo, and I went on the shoot with him. His instincts, using the bow of the ship or curve of the swimming pool as a graphic element was exactly what I wanted.

MJ: You’ve been doing this a long time—what’s the appeal of the job?

JM: The business has changed a lot, and I’m lucky to have a job where my opinion matters and I have a lot of creative freedom. There’s a bit of a trend towards photo editors serving more as producers, while creative directors will pick all the photographers. There’s no fun in that for me.

MJ: It has to be gratifying though. I know that in my career, my collaborations with photo editors were instrumental to my success.

JM: Oh absolutely, and my happiness comes from working with the photographer and creating something together. That’s the exciting part; last week I assigned a photographer I met four years ago when I was at New York magazine. I never got to work with him when I was there, but I just found an amazing story for him in Florence. I love it when I can finally assign a photographer that I have been obsessing over for years.

YOLANDA CUOMO AND BONNIE BRIANT: GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Over the course of writing this book and interviewing the contributors one topic kept coming up: the importance of the mentor/apprentice relationship.

The importance of a strong role model/teacher/advisor/mentor to the apprentice is obvious: The pupil has the opportunity to learn at the elbow of a master. But the flip side of the coin is often overlooked: What does the mentor get from the relationship (aside from cheap labor)?

I’ve been on both sides of the equation. As a young artist beginning my career I had great teachers from many different walks of life in many different fields. People who taught me bigger lessons than how to change a lens, or position a light. They taught how to lead from the front, and how to go beyond the expectations of clients. These were lessons that transcended technique or prowess.

But as a teacher and professional photographer I have enjoyed my role as a mentor equally, and my dirty little secret is that I am certain I get much more than I give in my role as the teacher/employer. I often say that I teach because it gives me eight hours a week to be an idealist, and my assistants, young and wide-eyed on their first big shoots, remind me that my profession is a privilege. Any creative professional who has allowed himself or herself to become jaded is poisoning the well.

Yolanda Cuomo has been a legend among photographers for years. Beginning with her years at the elbow of her mentor, Marvin Israel, Yo (as she is known) has enjoyed a career collaborating with virtually every great photographer of the last quarter century. To be sure, her success comes in no small part from her formidable personality and great good humor. Yo is a riotously fun person to spend time with, but that observation should in no way diminish the quality of her work or the depth of her accomplishments, which would take up more space than I have allotted for this entire interview. Perhaps these three small bullet points will serve to impress:

• She designed the Richard Avedon retrospective at ICP in 2009.

• She designed Revelations, the definitive retrospective exhibit and accompanying book for the work of Diane Arbus.

• She was the lead designer for Aperture magazine for 13 years.

Bonnie Briant is a young fine-art photographer who studied with Yo at NYU. After starting as a student intern, she has been an associate designer at Yolanda Cuomo Design for four years.

Their collaboration should serve a model for what every mentor/apprentice relationship should be. Together they get a lot done, have a lot of fun, and do some astonishing work.

Interview

BB: [to Yolanda and I] You guys went to college together—how is it that in a school as tiny as Cooper Union you two didn’t know each other?

MJ: It is strange; I graduated in ‘78—when were you there?

YC: I transferred from Montclair State to Cooper in ’78, but I hated the photography and design department at Cooper. I spent more time with the conceptual artists who were doing film and sculpture like Hans Haake and Robert Breer.

MJ: Well, now that makes sense to me, because while Cooper was, and still is, famous for graphic design, your work has no family resemblance to any of the design that was going on at Cooper in the late seventies and early eighties which was typically so clean and refined …

Bonnie Briant (left) and Yolanda Cuomo

YC: Oh it was so awful! It was all Helvetica! You know, by the time any designer graduated from Cooper they were all doing the same thing, they were all completely interchangeable. Cooper was all Bauhaus, and I was all CBGB’s!

I did an exchange semester at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and I did a lot more photography there. I had my own color darkroom there. I always made books of my photographs. I was never interested in seeing them hung on the walls. I liked books, I always loved books; they have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

MJ: So if you didn’t study design at Cooper where did you learn design?

YC: I got out of school and I didn’t know what to do. I had a friend of a friend—one of those things—and I got an interview at Condé Nast to work at Mademoiselle doing paste-ups and mechanicals, I didn’t know what a mechanical was; I had to call a friend to find out what it was.

I got the job at Mademoiselle, and eventually I met Marvin Israel there …

MJ: The legendary Marvin Israel …

YC: Yeah, but I didn’t know who he was. He was designing a poster for a retrospective of Alexey Brodovitch’s work …

MJ: Another legend …

YC: Right, but again I didn’t know who he was either. Marvin starts pulling type and pictures out of his pockets and sticking it to the poster with tape. He was doing design like he was a painter. I said, “You can’t do that!” and he said, “Why not?”

The poster for the Diane Arbus “Revelations” retrospective and book

Cuomo Design

Marvin Israel’s poster for Alexey Brodovitch’s retrospective

Cover for Aperture magazine

Credit Line: Yolanda Cuomo

It was a revelation, and suddenly I saw how creative design could be. Marvin liked me because he didn’t have to unlearn me; he was fantastic to work with. He was really my design teacher, and then later he introduced me to Avedon.

MJ: And what was your relationship with Avedon?

YC: He was really my sponsor. I met him through Marvin, and he loved the fact that I was designing photography books, but of course they paid nothing, so he would give me ad campaigns to design and those paid the bills.

MJ: I don’t understand. Big ad campaigns like that are handled by ad agencies—how could Avedon hire you to design a campaign?

YC: No, we were like a kitchen-table ad agency. Dick [Avedon] was the creative director—he’d make the photos and come up with the ideas; Doon Arbus would write the copy, Marvin or I would do the design. When Marvin passed away I inherited the job. We did the Dior ad campaign, and the Calvin Klein Obsession campaign—I did the storyboards and layouts.

MJ: And how did your relationship with Aperture come about?

YC: Melissa Harris [Editor in Chief of Aperture Foundation for ten years] was looking for someone to design Donna Ferrato’s book on domestic violence called Sleeping with the Enemy. She looked up on her bookshelf and saw a book I’d done; it was my first commercial book, called PrePop Warhol.

Melissa pulled the book out and just said, “This is the person I want to work with.” We met and a 26-year collaboration began. Then eventually we did a redesign of Aperture magazine and that lasted for 13 years.

MJ: The thing that’s interesting to me about your career—and this hard to articulate—I’ve worked with a lot of famous designers and art directors, and while you always manage to put your stamp on the things you’ve done, I’m not sure I can define a “Yolanda Cuomo” style in the same way I might easily recognize another designer like Massimo Vignelli for instance

YC: That’s good! That’s great! Because if you have a style, as a designer, then it means you have an ego that’s more important than the person you’re collaborating with. I want my design to serve the photography.

That’s why I love Bonnie. I hire kids who study photography because they understand photographs.

BB: Text, design, typography, they are all important to us as a design studio but the photographs always come first.

MJ: Right, and that’s what I’m getting at because when I look at the books, when you look at the studio’s portfolio, what you see is a meshing between the photographer’s work and the design. If it’s a photographer like Sylvia Plachy or Gilles Peress, then the design feels like it’s a collage or like pages from the photographer’s notebook. But if the photographs are clean …

BB: The books always look like they are a mesh because it’s all about the collaboration between us and the photographer. We listen to the photographer and we look at the pictures carefully. That’s the defining style of the studio; it’s deeper than something as superficial as a bunch of fonts.

An ad for Christian Dior designed by Yolanda Cuomo

Yolanda Cuomo

Yolanda on press with photographer Alex Majoli (center) and printer Roberto Piva (left), Verona, Italy, 2014.

Bonnie Briant

We never get a folder of photos and just make a book. We spent four hours today with a photographer working on the sequence, creating pairs, looking at the relationships between images.

YC: And that’s one of the things Bonnie brings to the table—I need another person there to argue with.

BB: Though she always complains that I agree with her too much.

MJ: [to Bonnie] And that brings me to you, as a person who studied photography—what do you get out of this relationship?

BB: I get a lot, actually. I think I get more out of it than I’m able to contribute.

YC: Not true.

MJ: I think you’re interesting because you studied photography and you’re still shooting as a fine artist. We were just in a group show together a few months ago, but you’ve decided not to pursue a career as a Professional. Why did you decide to pursue a career in design over photography?

BB: There were lots of reasons not to pursue a traditional professional photography career. It just wasn’t something that interested me, but I love this job. I think if I made photos all day as a professional then I wouldn’t make art. This job affords me the freedom to do my photography the way I want to do it and still have a job that is creatively fulfilling in a different way.

The best part, aside from working with Yo, is the chance to spend time with so much incredible work and so many amazing photographers.

Right now I’m just cleaning up the files on a Gilles Peress book, and it’s a complete lesson in photography just to spend so much time with that work.

MJ: So tell me what the day-to-day routine is like here.

An iPhone/iPad app accompanies the catalog/book for the Library of Julio Santo Domingo

Cuomo Design

BB: It depends on the time of year. We just finished summer production. So we just got back from getting a book printed in Italy where we were “on press” [quality control of the print process].

MJ: So there’s a yearly schedule?

YC: Yes, because most of our books come out in the fall. So things are slow now. We’ll start looking at photographer’s projects and deciding what projects we want to do this year.

Today we spent the day, about four hours, with a photographer. Just looking at her work, and we started the sequencing.

MJ: But wait, aren’t you hired by a publisher once the photographer has a publisher in place?

BB: Sometimes, but mostly now we are packaging the book with the photographer and then we’ll help find the publisher and distributor, but more often we’ll start with the design and then the photographer will figure out a way to pay for it. More and more photographers are self-publishing and self-distributing.

MJ: Really?

YC: You know how you hear photographers say “books are dead”? Books are not dead, they are more exciting, and there’s a bigger market than there ever was. And there’s an appetite and a market for photography books that didn’t exist in the past.

The way books were done in the past is dead, but books, especially photography books are bigger than ever.

MJ: That’s exactly why I’m writing this book. I hear photographers my age complaining all the time, but the new generation is thriving because they aren’t attached to the old business models. At least six of my ex-assistants published their first monograph before they were 30, but not with traditional publishers.

YC: Exactly. For instance, we just had a project come through here … Wonderful photographer who shot John Cage all through the seventies, but there were over 200 photos that all needed to be produced and printed from the negatives. The great thing about having my assistants who are photographers like Bonnie and Jonno Rattman (another employee of the studio) was that we gave all the negatives to Jonno and he digitally re-mastered all the negatives and produced all the files. Having employees who know photography and are current with technology is invaluable.

In that instance the book was designed; then it was eventually published by Wesleyan University because they are the caretakers of John Cage’s archives.

And there are other projects, things that are about incorporating new technology with books.

MJ: I wondered about that. Yo, you seem very wedded to paper and print, but in a very non-traditional way.

BB: Last year we created a private app, to go with a book we did, for the Santo Domingo family, called “The Library of Julio Santo Domingo.” Originally we were contracted to do a 900-page book about this incredible—very eclectic—collection/archive, but the collection also included a lot of film and sound archives that couldn’t be shown in a book.

YC: Right, so when we were in the meeting with them I just sort of pitched it to them, “Hey! Why don’t we do an app to accompany the book?” [laughing] I had no idea what I was doing! I had never created an app, but we did it and we’re really proud of it because you can watch film clips, listen to music—it’s great!

New York, September 11, by Magnum Photographers; designed by Cuomo Design

Cuomo Design

MJ: Well, that’s one of the great things about having relationships with assistants and students. They’ve really helped to keep me current with technology; having young people around, people who are excited by the possibilities of technology helps to keep me interested.

BB: I think a lot of being successful, or at least one of the reasons this firm is so successful, is because we are willing to say “Yes” and try things we’ve never done before and have the confidence to know that we’ll figure it out.

YC: And invent …! We’re always inventing! I sometimes call Bonnie the “Mathematician” because the books, especially our books, can be very complex in their construction; some of our books incorporate multiple double gatefolds, multiple-page accordion folds, that kind of thing. Figuring out how to physically produce the book can be a real challenge, but Bonnie’s like an engineer … Printers will tell us that something can’t be done and then Bonnie will say, “What about if we tried this …?”, and the next thing you know it’s done.

Making a book is like making conceptual art or making a film, but sometimes we’re just sitting here folding paper, folding it this way or that, tucking one fold underneath another one … just trying to figure out what’s possible. It’s a lot of problem solving.

BB: It’s funny because she’s looking at it as a film or conceptual art, while I’m looking at it as a series of small jigsaw puzzles.

MJ: So, Bonnie, what’s your long-term plan?

YC: (laughing) Her long-term plan is that she never leaves here!

BB: She’s joking but it’s kind of true. My long-term plan is just to keep growing in the way that I’ve been growing now, and this is a great place for me to do that. I can’t imagine a better place.

I’m not going to have a big photography career. I don’t want that. I just want to make the photos that I like to make, and hopefully other people like as well. I love doing design for a living. Maybe someday I’ll have my own design studio, but for now, Yo is probably the best role model I could have hoped for. It’s incredible that we only get to do good work and deal with the best photographers.

You know, we do a lot of war and disaster books. We did all the 9/11 books, so on some level you might think, “Wow that’s depressing.” But the fact is the books are all great books with great photography. At the end of the day, I’ve been dealing with great photographs all day. This place has really spoiled me because I don’t know if I can step down from this level and I’d probably have to if I went to work somewhere else.

The great thing, and maybe I’d mention this as a piece of advice to young people looking for a mentor, is that you want someone who’s a boss, but someone who also takes you and your ambitions seriously.

Maybe someday, I’d like to have my own studio, but that’s a long way off and my goal is really to work with images that I like and people that I like.

This studio is a really happy place and one of the most important things I’ve learned here is that having your work environment be a happy place is a possibility.

MJ: Well, if there’s one point I would like any reader of this book to come away with is that business isn’t “boring business.” The most successful people aren’t the ones who came up with a plan to make money; they are the ones who enthusiastically take on challenges and create careers that they enjoy. Otherwise it’s too much work, and too much time, but when you enjoy the place you work, and the people you work with, then you don’t resent the time you have to put into it. It creates a better, stronger product, better work, and people will always pay more for good work.

In a way, I don’t think success makes you happy, so much as happiness makes you more successful.

YC: It’s true. My staff and my clients are my buddies. Who do you spend all of your time with? Your family and the people you work with, so you should do it with people you like, and the money/success will happen.

MJ: So this question is for both of you: What was the attraction to design as a career?

YC: I needed a job. It was probably that simple, but I also hated being by myself and if you’re a painter, or a photographer for that matter, you spend a lot of time, too much time, by yourself.

I just love being with people, and it’s the daily invention that we do, and the collaboration with other artists that I find so rewarding. It’s so exciting because you never know what you are going to make because it’s a different mix of creative personalities on every project. And every project has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

BB: I think I’d second much of that. I love the collaboration, and I love the inventing, but I think what I really love is the physical object. I love seeing the thing we produce and thinking, “Yeah, that’s what I’ve been doing for the last three months.”

YC: I just think sometimes, “How was I so lucky to find my groove?” I know I’d be an unhappy person if I hadn’t found this career.

JAMIE ANTONELLI: DIGITAL IMAGING SERVICES SUPERVISOR, SANDBOX STUDIO, NYC

www.sandboxstudio.com/locations/new-york

Many students enter traditional photography programs with the dream of becoming photographers, but since the advent of digital imaging more and more of them find themselves fascinated with computers and image manipulation.

Jamie Antonelli was the first student I ever had who used digital manipulation to produce thesis-level work that transcended the schlock that was typical of the late nineties. As one of his undergraduate teachers his work forced me to reevaluate my own prejudices and preconceptions about what photography could be. For Jamie the computer was a studio that was almost a real physical environment, a space where he could challenge himself and create something new.

Interview

MJ: So here’s why I thought you were an interesting person to include in the book. You entered NYU as a freshman in 1997 and graduated in 2001. When you came in as a freshman Photoshop had only been out for a short time and it wasn’t in widespread use. In fact our curriculum for including computer imaging was still very experimental at the time, but by the time you graduated Photoshop was a fixture in the industry.

You came into NYU wanting to be a photographer but left with a completely different career path. The career you have now didn’t exist when you entered college. What was your original career plan, and why did it change?

JA: When I applied to NYU I wanted to be a traditional photographer; my dream was to travel all over the world shooting for National Geographic or something. I always think it’s funny that I originally wanted to be a photographer so I wouldn’t sit at a desk all day, but now I sit at a desk all day.

MJ: I say the same thing all the time, but I still have no patience for sitting at a desk, which is probably why I’m still not as good at Photoshop or video editing as I should be.

JA: I really became interested in Photoshop when I was in my second year of photography school at NYU. One of my teachers, Jeff Weiss, was the first person to teach me realistic photo manipulation. I liked the process of compositing photos, and Jeff was the first artist I had met who was making really interesting work using Photoshop. He was really the inspiration.

MJ: And I would say that you were also the first student I had who used Photoshop for a fine-art project in an interesting way. Up to that point everyone was doing these very lame fantasy scenes.

So when you got out of school what happened?

JA: I got a job immediately. At the time, demand for Photoshop skills was exploding. I had done an internship at a retouching company called Robert Bowen Studio for two summers when I was in school. I learned a lot from Bob in a short amount of time. Plus, I was able to work on some amazing accounts and build up my portfolio, which helped me get my first job.

Jamie in the Lobby at Sandbox studios NYC

My first job out of college was at a studio called Image Consortium. I was working there only a few months until September 11, 2001. That company closed shortly after, and for the next few years I freelanced for a number of other photography and post-production studios in New York like Pixelway and The Lab.

In 2003 I became the Digital Coordinator at the Photography and Imaging department at NYU. While working there I received my master’s degree in 3D computer animation from the Center for Advanced Digital Applications at NYU. After graduating in 2006 I moved to San Francisco to work at a retouching/pre-press company called DMAX Imaging. While in San Francisco I met up with the Imaging Director for Sandbox Studio. Sandbox was just opening their retouching department in New York and I moved back to work for them in 2008.

MJ: And what’s your official job here?

JA: My title is Digital Imaging Services Supervisor.

A stylist at Sandbox preps a handbag for a photographer.

The majority of what I do is overseeing all the post-production for a major retailer. It is my big, ongoing account, but I also handle any advertising or editorial work that comes through the studio.

MJ: So maybe I’m not quite clear what Sandbox is, or does. I’ve always thought of them as a one-stop studio for smaller companies or designers who need a “one-off” catalog or look-book, but just from looking around I realize that I’m completely wrong. You have huge clients and major brands, and the work is constant.

The Computer Imaging Department at Sandbox, NYC

JA: Definitely. We have grown tremendously in the last few years and now have offices in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Portland, Memphis, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. A few of the New York clients we handle are Coach, Tommy Hilfiger, David Yurman, and Kate Spade. The client list is huge and very “A” list. But you’re right in the sense that we are a full service one-stop studio that handles all photographic production from start to finish. We hire the photographers, digital techs, stylists, models, do all the post-production, then deliver the finished imagery as a complete package to the client.

MJ: Mostly for e-commerce and catalog?

JA: Well, Sandbox was started as a way to service clients who had a need for large volumes of photography so e-commerce photography is our bread and butter, but we also work on editorial and advertising shoots.

MJ: See, it’s interesting because while certain fields in photography are suffering in the current market, others are exploding. Sports photography, in the traditional sense, of spot news coverage, I think, might be dead, but e-commerce is a gigantic new market.

One of the fashion studios at Sandbox with a solid “cyc”; short for cyclorama. Cycs are used on highend fashion shoots instead of the cheaper and more common “seamless” paper backdrops. A cyc is a solid structure that allows the model to move freely without tearing paper. Because it is also curved at the top the photographer can shoot from low angles and still make the model “float” in space without seeing the seam between the wall and ceiling.

JA: You think sports photography is dead?

MJ: In the traditional model of sending a photographer out to cover an event as a photojournalist. When a sporting event is being telecast using 4K (ultra HD) video cameras why do you need to send a photographer when you can pull a still from the video feed? Maybe “dead” is an exaggeration but it certainly isn’t a growing segment. But studio product photography is bigger than ever and we’re also seeing more and more motion/video clips on traditional e-commerce sites.

JA: We are doing more of that as well within Sandbox. The company has done some e-commerce video shoots and is even creating social media video content for some of our clients.

MJ: And what’s a typical day like here? What do you do?

JA: On a typical day I’ll start by going through emails and priority lists to ensure that we are on time with what is due on our post-production schedule. Next, I’ll review the art director’s notes and retouch their specific markups per image. I’ll usually retouch around 15 images a day. We use proprietary web and database programs that track every file. At any point I can pull up a filename and it will tell me what stage of production it’s in. This is great for a supervisor like me working in high volume so I can keep track of the whole workflow. Then I’ll cross-check the completed images done by other retouchers and send them out to be reviewed by the account’s art directors. Later, I’ll go through and make additional corrections to images that have further markups. Once they are approved, I’ll deliver final files to our FTP server.

[Jamie starts to open a few images on the computer so he can show me some examples.]

MJ: How many people answer to you?

JA: On a busy day I could be overseeing the work of three retouchers.

MJ: So four people working on fifteen images a day?

JA: Yes, but it depends on the art director and how intense the markups are. Some require more work than others.

MJ: And are you working on images by the same photographer all the time?

JA: Yes. They want to keep a consistent look on set with the lighting and feel of each shot. That way the post-production department doesn’t waste time fixing unnecessary variations and can focus on the specific retouching tasks at hand. It’s all about efficiency.

[The files open up and we start studying the art director’s notes and individual layers of the images.]

JA: So what we can see here is that we have chosen a designated “Hero” for the flesh tones for this specific model, so that her flesh tone is matched through the whole shoot regardless of the color of the clothing.

MJ: Really? So how do you match the color on the clothing? Do you have a program for that?

JA: No, we physically pull the merchandise sample from the rack and match it by eye.

MJ: You’re kidding?

JA: Not at all. We’ve tried different ways of doing it with digital swatches, but nothing works as well as a person with really good color vision matching it by eye. And since the images have to work for both online e-commerce, which is an sRGB color space, and the printed catalog, which is a CMYK color space, it really needs a trained eye to make the evaluation based on the usage.

The photographer’s original file on the left with the retouched version on the right. Aside from the obvious retouching of the monofilament holding the straps and the changes in contrast and color there are also a multitude of subtle changes to the surface of the bag that are probably not readily apparent in this reproduction.

Sandbox Studios

These additional color variants are all from the original file with the new colors created electronically but color matched by Jamie’s eye. Using the same file ensures that the styling is consistent throughout the catalog.

Sandbox Studios

MJ: So going back to your start. What was it that attracted you to digitally manipulating images?

JA: Originally I enjoyed compositing and enhancing my own photography and artwork. I liked the way it combined drawing and painting with photography. The work I made in college helped me get my internship and that transformed into a career that has allowed me to support my family. It’s also a very portable skill. When we moved here from San Francisco I was able to get a job immediately.

MJ: Sandbox seems like it’s a pretty nice place to work.

JA: I love working here. They treat me well and I work with great people.

MJ: So if someone wanted to get a job here, what would be the procedure?

JA: Well, I have to say that the level of expertise here is extremely high. These days it seems like everyone has Photoshop but there is a lot that goes into being a good retoucher. It’s all about being subtle; the trick is to make it look like it hasn’t been retouched. Some of what we do is very intricate work and it has to look seamless and completely real. It also has to be consistent throughout large imaging campaigns. Generally we don’t have the time to really train someone, so they need to be experienced enough to hit the ground running.

When we interview retouchers they are given a three-part retouching test. If they do well on that then they are brought in on a one-week trial.

EMILY HOSKIN OF ALAMY, STOCK PHOTOGRAPHY AGENCY, UK

Millions of photographers shoot billions of photographs every year, but where do they all go? That great vacation photo you shot of the sunset over the Grand Canyon, or that one of your niece dancing at her Bat Mitzvah. What becomes of those photos?

The vast majority of the images we make will languish in boxes of negatives or written in digital code onto hard drives, never to be looked at again. Most of the photographs we make are for a very select audience. Whether it’s for our family album or a specific magazine assignment, we often assume that no one else will be interested in the image past its immediate purpose.

But suppose I am a photo editor for an Australian travel magazine, or a Muslim sociologist in Yemen writing a textbook on the coming of age rites of Jewish American teenagers? I might just need, and be willing to pay for, exactly the photo that you shot.

Stock agencies collect millions of photographs every year and curate these images into searchable databases that can be accessed and browsed by a worldwide market.

After studying photography at two major universities in England, Emily Hoskin was as committed as ever to her love of the medium, but like many young grads fresh out of school Emily had decided that the life of a professional photographer was not for her. Luckily, she happened upon a job posting that fit her like a glove …

Interview

MJ: So there are really three topics to ask you about here: Your personal career path, Alamy, and licensing/stock photography in general. But let’s start with you. What was your background before you went to work for Alamy?

EH: I studied at university for four years in all. The first three years were at Birmingham University where I studied Media, Culture, and Society. It was all theory based, and very interesting, but I really wanted a more practical education so I transferred to the University of Plymouth, where I studied Media Arts, which was 90 percent practical.

MJ: And how did you come to Alamy after you graduated?

EH: By the time I graduated I knew that being a photographer wasn’t for me. I just needed more financial stability than that. But I also think that when you start out in school you are blessed with a kind of naïveté and I assumed I’d become a famous fashion photographer shooting for Vogue. When you get out of school and the cold light of day hits you, you’re faced with the fact that even shooting for the local newspaper is a very competitive field. The idea of being an average photographer had no appeal for me. If I wasn’t going to be great, I wasn’t going to do it.

MJ: So how did you end up at Alamy?

EH: I was working at a local gift shop in Oxfordshire, which was destroying my soul. I had a degree in photography that I had worked very hard for, and couldn’t bear a job wrapping packages. I started applying for any job I could find that had the word “photography” in the description. There weren’t many in Oxfordshire, but I was willing to relocate. Then I saw an advert for a job in Oxford, about 20 minutes away, and that happened to be Alamy.

I didn’t have a clue about stock photography; it wasn’t anything they taught us about at university. But Alamy was looking specifically for someone young and straight out of college.

MJ: And you were hired to do what exactly?

Emily Hoskin of Alamy Images

Jason Smith

The splash page for Alamy’s website

Alamy

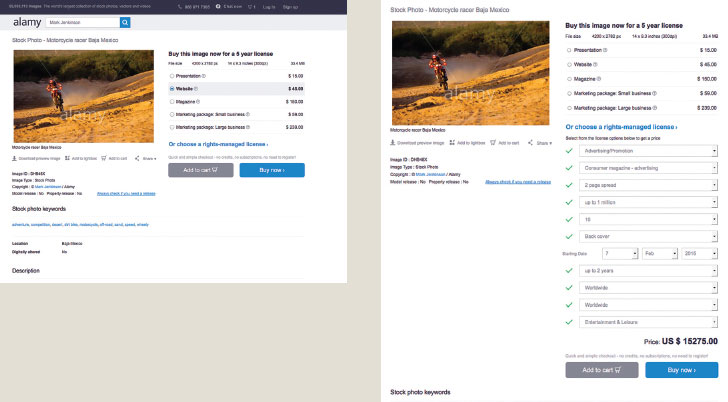

Using Alamy’s drop down pricing guide we can see the dramatic differences in how usage affects the pricing for this “rights managed” image. A one time web use prices the image at $45. The same image used for advertising and placed in various magazines is priced at $15,275.

Alamy

EH: I was hired as a Brand Ambassador for Alamy where my main responsibility was to create and promote the 100 percent royalties Student Photographer Project; that’s why they wanted someone straight out of university. They wanted someone who could relate to student photographers. Really, it’s my dream job—I’m involved with photography, I get to travel all over the world and recruit amazing young photographers.

MJ: So tell me about the Alamy Student Photographer program.

EH: In a nutshell, any currently registered student can place their images with Alamy for worldwide syndication. When/if the images are sold or licensed for use by a third party the student gets 100 percent on the royalties for the image. After two years, the percentage drops down to our normal split of 50/50, which is still the best in the industry.

MJ: It is a great program; I admit that I was bit skeptical when you first approached me about getting my students involved. Over the years I’ve seen so many ways that students are taken advantage of, but the Alamy student program seems like a win/win for everybody. The students have a chance to make money from their images and Alamy draws in a pool of loyal young talent with fresh imagery.

As a side note, one of my favorite side benefits of the program is that it gives the student access to industry standard price guidelines. I have students and alumni calling me all the time after they have been contacted by an ad agency or magazine that wants to use an image that was found on their personal website or Flickr. In one case the ad agency wanted exclusive use of the image for a worldwide ad campaign for a camera manufacturer as a double-page magazine advertisement, they offered the student $1500, which sounds like a lot of money to a college student …

EH: [laughing] When of course that usage should be in the neighborhood of a $10–20,000 use fee, or even more, depending on the specifics …

MJ: Exactly. So one of the nice things about Alamy is that you can use the Alamy web interface to find out exactly what the industry standard licensing fee should be, and if the photo is sold through Alamy (and the student is still in the student program) all of that fee goes directly to the student.

But you knew nothing about the stock industry when you applied for your job right? How did you even qualify for the job? How did they train you?

EH: Well, they trained me by having me rotate through all of the different departments within Alamy. I spent a few weeks in Customer Service where I learned about how licensing works, how we sell images, how we bill images, and about model/property releases. Then I went through Content, which is our interface with the photographers who create our images, I learned about how we do quality control (inspecting each image for technical flaws, file size, etc.) and the flow of all the images as they go through the Alamy system.

MJ: So let’s move onto the bigger topic: Can you give me your most succinct explanation for what stock photography and image licensing is?

EH: Simply put, it’s a way for clients, advertising agencies, magazines, businesses, etc., to purchase the use of an existing image or images without the necessity of commissioning a photographer. Licensing allows the client to buy or “rent” the right to use an image for the specific use and length of time that they need it for. There are two distinct ways that images are licensed: “royalty free” and “rights managed.”

Let’s use a bank as a typical client. Perhaps they need a simple photo of a hand counting out bills for a pamphlet or website. If they don’t care about having an exclusive rights to that image then they might buy the rights to use an existing image from our royalty-free image collection and pay a rather small fee for the non-exclusive rights to that image, for whatever use, in perpetuity. The image will be priced according to the size of the image, which in this example is quite small.

However, if they want to purchase the rights to an image exclusively (meaning it will not be licensed to another client or a competing bank) and they want to use it for a variety of specific uses, billboards, advertising, etc., then they will have to choose an image that is rights managed and probably pay a considerably higher fee. Rights-managed images are always priced specifically for, and commensurate to, the way the client will use them.

For clients there are a lot of advantages to using stock photography. The most obvious is that they know exactly what they are getting, but another is that they have access to browse a far greater variety of photographers and styles of imagery. They know exactly how much they will have to pay for their specific use. They also know that there won’t be any other legal issues in the future. All of these factors give the typical stock client a lot of peace of mind.

MJ: So let’s look at the process from the point of view of the client. How do they find the images?

EH: Right, well that brings us to the idea of “keywording.” The first thing a client will do is log onto our site and begin a keyword search. So you might start with something like “hand” “cash” “money” and that might bring up 2000 images but probably most of them aren’t quite right, but adding the keyword “count” or “counting” will probably narrow the search quite a bit. However, there might be other words like “transaction,” “commerce,” or “exchange” that are more conceptual and might yield a better or very different result.

A client with some experience, like a professional art buyer or photo editor, can narrow the search very quickly and efficiently by specifying limitations to the search, like whether they need a vertical or horizontal, color or black and white, or how many people they want in the image, etc.

For rights-managed images, once they have found the image they want then they use our drop-down menus to define the type of usage, the location of usage (regional, national, or worldwide), and finally the length of time they need the image. Then they simply pay for it and the image is made available for download.

MJ: Of course all of this depends on the keywords, and each photographer that contributes images to Alamy is responsible for keywording their own images, so the photographer really has to think about that when he/she submits the images.

EH: Yes, keywording is central to the whole idea of the search, so if a photographer is really bad at keywording his/her images they could end up at the bottom of the pile. Personally I feel that it’s best for photographers to do their own keywording because they know why they took the photograph, they know best what emotion or feeling they were trying to convey.

Keywording images is something you get better at with practice. There are also online services that will keyword images for a nominal fee.

MJ: Keywording is tricky. I find it useful to revisit images in my collection and add keywords a few months after I submit so that I’m looking at them with fresh eyes. Now let’s touch briefly on the difference between rights-managed images and royalty-free images.

EH: Rights-managed images are priced according to the type of use, duration of use, and region. Royalty-free images are purchased according to size. Once someone purchases an image for royalty-free use they can use it for as long as they like and as many times as they’d like. This means that royalty-free images are never exclusive to a particular customer; many different clients can use them.

MJ: So the obvious problem for a client is that they could end up using the same image as one of their competitors. Clients have to pay a premium to have the exclusive rights to use a particular image in a particular market.

EH: Exactly, it also means that photographers who choose to sell an image according to either the rights-managed or royalty-free marketing models have to make a conscious choice. A rights-managed image might only sell once, but it will most probably sell for a higher fee. A royalty-free image might sell hundreds or even thousands of times at much smaller fees based on size. A very experienced stock photographer might have a pretty good sense of when to use one method over the other and they can choose either based on the individual photo. It also bears noting that any photograph that is being marketed as royalty free must have all the proper model and property releases in place.

Many photographers don’t like the royalty-free model much because they aren’t sure that they are getting top dollar, but many clients love it because they can feel secure in the knowledge that the photo is properly released and that they can use it for as many different uses as they like without having to pay for it over and over.

MJ: And that brings us to one of the other things I particularly like about Alamy, which is that as a contributor you manage your own archive. You can add or delete images as you like at any time. You can revisit images and change keywords.

MJ: So that’s a good synopsis of what stock does for clients, but what would you say stock does for photographers?

EH: Well, of course my main contact is with photo students, but it’s true across the board that photographers get an outlet for their work and stock is a long-term investment. Once the photographs are on sale they can generate income for as long as the images are relevant to the market.

MJ: Yes, although I personally find that I can never really predict what will sell. I have some fairly ordinary images that I shot on assignment that have literally sold every month (somewhere in the world) for over ten years, and other ones that I think are spectacular that have never sold. Consequently, I never looked at stock as a way to make a living—it’s just an ancillary income for me—but I always wonder why more photographers don’t do it.

If you are really a photographer then you are shooting all the time, every day, and you will inevitably see things that might not fit into your primary interests but are still valuable images.

EH: And aside from the money I think that almost any photographer is gratified when they see that their work has been used and published in some way.

MJ: We should talk about model releases for a moment because they are very important and central to the entire topic of stock photography. I do know that the rules are different from country to country. In the US you can use any photo of a person for editorial use (newspapers, magazines, etc.) even if there is no signed model release. However, if that same photo is going to be used for commercial use (advertising, corporate brochures, or websites), then the photographer must have a signed model release from every person in the photograph. It stands to reason that it’s very important to get releases whenever possible because the fees for commercial use of any photograph are much higher than the fees for editorial use.

EH: And even if there is a signed release, there are times when we need to go above and beyond to insure that the person depicted in the photograph is comfortable with the use.

Let’s say you have a photograph of a specific little boy with a black eye, and a hospital wants to use the photo in an ad campaign about how sensitive their emergency-room physicians are. As long as the photo has a standard model release it’s unlikely to be a problem. But suppose someone else wants to use the same photo in a public service advertisement against child abuse; in that case we would go back to the photographer and ask them for a “sensitiveuse” release.

In those cases the photographer might actually set up a special shoot specifically for that kind of unlimited stock use. The photographer would hire a professional model, who is being paid for their cooperation and the model (or guardian) would sign a sensitive-use release.

MJ: To change the subject completely … you are traveling all over the world explaining the stock photography industry to photo students. What is the question you get from them most often?

EH: We’ve covered most of the big ones, but I am always surprised that so few of them ask about how to get involved in the stock photography industry from the agency side.

MJ: Honestly, that never occurred to me either, but that’s a great point because your job actually gives you the training for a very versatile, and portable, set of skills. If a young photographer learned about stock from the agency side it would prepare them for a variety of career options later on. You would learn how to shoot and sell your own stock photographs, which means you could travel all over the world, live anywhere, and simply shoot the photos that you want to make. Or you could transfer those skills into a very lucrative career as an art buyer at an ad agency, or become a professional picture researcher, photo editor … There are so many options.

EH: Exactly. Everyone asks about becoming a stock photographer, but no one ever asks me about careers in marketing stock photography.

I love my job, but I also work with an amazing team of people and every aspect of the company is quite fascinating. Within Alamy there are so many other interesting jobs. Our quality control department looks at every single image that comes through Alamy. Our marketing department promotes our brand, and sells the images. We have people who recruit videographers, which is an exciting and new industry. We have an amazing director of photography who is actively meeting with, and recruiting, photographers all over the world. There are people who work in our IT department who are on the very cutting edge of technology. The legal department is always dealing with interesting situations. I often say that I’d be perfectly happy to do 50 percent of the jobs at Alamy.

It’s also pretty fascinating if you think about all of the different customers you get to deal with: Your clients are newspapers, design agencies, private businesses, book designers, ad agencies, top magazines. You are looking at news stories and history-making events from all over the world. Working at Alamy you are exposed to all of it. It’s a remarkably creative field.

JACQUELINE BOVAIRD: SENIOR AGENT, LEVINE/LEAVITT

Earlier in this book I spoke about the differences between strategic alliances and tactical alliances. To recap: A tactical alliance is one where the relationship is strictly monetary, it is day-to-day, and it can be terminated at anytime by either participant (labs, printers, rentals, assistants, other suppliers fall into this category). Most clients are also tactical alliances as well because they are hiring you for a specific job. Strategic alliances are more permanent relationships, partnerships really, in which both parties depend on each other for their financial well-being, and share in the profits.

One of the most important strategic alliances a photographer can make is with an agent, or artist’s representative. In the best cases it is a very much like a marriage, and carries many of the same contractual benefits and liabilities. The agent and photographer begin by agreeing to share in profits and dividing responsibilities.

A photographer’s agent is a business partner responsible for promoting the photographer’s work, dealing with clients, negotiating fees, writing estimates, and invoices. In most cases the agent will also help with the production of major shoots and smooth out difficulties with clients (like requesting additional work that was not defined in the original estimate). Depending on the agreement the agent will usually receive 25–40 percent of the photographer’s total billings, including existing “house” accounts. It is important to remember that the agent is entitled to this percentage whether or not the agent actively solicits the work.

In theory this arrangement frees the photographer to do what he/she does best, make stunning images.

The analogy to marriage is not an exaggeration; this is a contractual relationship that is difficult to terminate (agents typically collect fees for a year or two after termination). Your agent is a person you will deal with daily; it is essential that you not only trust and respect each other, but that you also genuinely enjoy each other’s company. Your agent is your representative in every sense of the word. They have to share your artistic vision and promote you as a unique artist.

Jacqueline Bovaird was a student I didn’t know well for most of her time at NYU until her senior year when she enrolled in my “Business of Art” course. In that class I had another photographer agent come in as guest speaker to discuss her career; the unique challenges and rewards of the profession struck a chord for Jacqueline, and by graduation she had her future mapped out.

In hindsight, becoming an artist’s agent was a natural fit for Jacqueline; she was charming, self-motivated, very smart, and very interested in the challenges of business. Now, just six years later, Jacqueline is one of the best agents in the business and a regular guest speaker in the class she once attended as a student. Below is the Q&A from this year’s visit.

Interview

MJ: So let’s start with telling the students a little synopsis of your career and how you got started.

JB: I graduated from Tisch P&I in 2008, and while I enjoyed making photographs I also knew that I wasn’t the kind of person who was going to be very good at hustling for myself. It comes more naturally for me to talk about someone else’s work and to see their work in the broader context of the industry. Since I do love photography and being around images, I thought I could use this enthusiasm working for other people that I believed in. For me, promoting other photographers is a lot more fun.

A snapshot of Jacqueline Bovaird with the portfolios of all of her photographers laid out for a presentation at an ad agency.

Jacqueline Bovaird

When I got out of school I definitely had bills to pay. I worked three jobs: I was a junior assistant at a photo-agency called Glasshouse Assignment, a studio manager for a photographer, and a freelance photo editor at the Wall Street Journal Weekend, which was a job I got through an internship I had as a student. Interning as a student is really important and the relationships you create there are as valuable as you make them. All the jobs I got when I graduated were referrals from my internships.

Through those three jobs I was able to see and experience a few roles in the industry and I realized that being an agent was a perfect fit for me. Glasshouse is both a stock and an assignment agency. The assignment division was, at the time, in a bit of a crisis. There simply wasn’t enough time or energy to go around, to move the agency forward in the way it needed. The president and owner, Spencer Jones, really supported my ideas and was very influential in developing my love for this job. He had this overly ambitious girl straight out of college with lots of ideas, so he basically threw me a ball to see if I would run with it. I was put in charge of the assignment division of the agency. Spencer allowed me the freedom to make mistakes I needed to make to learn and grow, and was always the first one to celebrate our successes. Within a year we had overhauled the agency together and things were moving forward very quickly.

I designed their books, managed client relationships, built their database, wrote their contracts, estimated their jobs, and I even got to sign a few new photographers that I admired. I also wrote the blog for them for many years, Stone Thrower.

My experience with Glasshouse brought me to the attention of an established agency called Vaughan Hannigan, where I worked as a senior agent for over three years and had the opportunity to represent incredible artists and clients. In the spring of 2014 I was approached to join the team at Levine/Leavitt, which was always an agency I looked up to greatly because of the caliber of artists they represent, as well as their reputation for being both amazing people and incredibly professional. I was hired as a senior agent to take on the role of managing their West Coast office in Los Angeles. Through all the jobs I’ve had it has been very important to me to maintain relationships with the artists, and many of them are among those I call my closest friends.

Jacqueline doing a presentation on her career for a class of photo students

Jeff Levine and Elizabeth Leavitt have conceived and built the company as a smaller, exclusive, boutique agency representing photographers, directors, and illustrators with both a fine-art and commercial appeal. Keeping the roster small allows each artist to get a great deal of attention, and allows us to manage his or her career carefully and effectively. We have amazing relationships with our artists as a result, and a rare camaraderie within the roster.

Our artists are all different: from illustrators, directors, and photographers ranging in still-life, to lifestyle, sports, and portraiture. All of our photographers also shoot “motion” in some way. At this point, we’re getting so many calls for integrated (still and motion) productions that our photographers are quickly building their reels as directors, and some are considered established directors as well. Each one of our artists maintains both a fine-art and a commercial career. Danny Clinch, for example, is a photographer based in New York. His aesthetic is so developed and recognizable that his commercial clients tend to hire him to do exactly what he does for his personal work. Another artist I worked with in the past, Martin Schoeller, also has a very strong fine-art career with his Close Up work, though his commercial work is much more varied. He’s well known for his celebrity portraiture for magazines and also does a lot of advertising work.

MJ: [interjecting to the class] It’s important to remember that magazines and ad agencies are always looking to the fine-art world for inspiration, so having and maintaining a fine-art career is an important way for you to have your best work out in the world and bringing in new clients. In the best of all possible worlds your fine-art career and your commercial career support each other.

Students looking through the portfolios of the photographers Jacqueline represents.

JB: The strict definition of my job is to introduce my photographer’s work to people that they wouldn’t be able to get to any other way, and then negotiate and manage projects that come in. My primary focus as their agent is to get them commissions, so we’ll help tailor their portfolios and manage their careers towards the clients they are trying to reach.

That being said, I have always considered the role to have larger parameters. In many ways I’m their co-pilot and we’re working together to push both our careers forward. We work together as a team on all aspects from marketing to portfolio edits to estimating. They must trust my judgment as their agent as much as I must trust their skills as an artist delivering work to our clients. We’ll also partner with them to help set up test shoots or personal projects for their portfolios.

Student question: Do all photographers have to shoot advertising?

JB: No not at all, but it is the highest-paying segment of the industry and a goal for most of my artists.

When our artists make money they’re able to do the work and live the life that they want. Editorial work is incredible and often said to be the engine that keeps your career running. My recommendation would be to sit down and clarify exactly who you want to work for and then just go for it. It matters less which parts of the industry these clients are in and more that you’re excited to be working with them. Some of these will be brands represented by advertising agencies, some will be magazines, and some will fall into other categories.

MJ: [interjecting] Also, ad agencies often won’t work with a photographer who isn’t represented because there are services that reps provide that ad agencies consider imperative. If an ad agency needs a revised estimate in an hour a rep can do that, but if I’m a solo photographer and I’m on a shoot that day I wouldn’t be able to accommodate the request.

JB: Yes, and conversely there are plenty of clients, magazines for instance, where they have an established one-on-one relationship with the photographer, so I might not be very involved at all on a magazine assignment because the photo editor already has a relationship with the photographer and it’s simpler to just deal with them directly. We work as a team to manage these client relationships in whichever way works best.