CAREERS AS A PROFESSIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER

Every fall at New York University I attend a weekend seminar with the parents of our incoming freshman class. My primary function at these events is to dress well, assume my most optimistic/successful persona, and assuage the concerns of a room full of nervous parents, most of whom would rather that their children pursue any other profession besides photography. I always fantasize about starting the talk by playing an old country song “Mommas, Don’t let your Babies grow up to be Cowboys”, made famous in a duet by Willy Nelson and Waylon Jennings.

No one becomes a cowboy, or an artist, to get rich. There are better ways to get rich: real estate, investment banking, or arbitrage for example. These are professions where money is both the means and the end. However, it’s also important to remember that while artists don’t become artists to get rich we all know that there are plenty of successful artists, musicians, and actors who are very wealthy. For that matter, I also happen to know a few cowboys who are multi-millionaires (raising cattle is a big business).

I also recognize that I am a hypocrite. I’m a photographer and my spouse is an actress. We live a nice middle-class lifestyle, but given our druthers neither of us would choose for our son to follow in our footsteps. That said, we would both support him in any career choice he made, even if that involved riding horses and herding cattle.

For artists, money is a means to an end. The goal of an artist is to create; money is simply a tool towards that goal, or (if there isn’t enough) an obstacle to be overcome.

If life were all about money it wouldn’t be very interesting, which might explain why so many wealthy investment bankers and hedge-fund managers spend so much money on collecting and supporting the arts. The world needs inspiration as much as, or more than, mere sustenance.

The allure for most young aspiring photographers is the stereotype as we are portrayed in movies and fiction. It’s a romantic image: we are dashing and brave, we travel all over the world, and we witness the historic events of our time. We socialize with beautiful models, celebrities, authors, and political power brokers. We create the images that define our epoch in history. We wake up every day to a new adventure. According to the Hollywood script, the lifestyle of a rock star pales in comparison.

At this point you are probably expecting me to tell you that this is pure myth, but I can tell you from first-hand experience that it’s all true. Really! Living the life of a freelance photographer is a privilege that is full of great adventures. The reward of this profession is that it dares us to be great, and demands that we are better today than we were yesterday. These are intangible perks that few other careers can match. We are responsible for our successes, failures, and the legacy of our vision. These are the rewards that make financial matters seem trivial.

Given this reality, who wouldn’t want to live the life of a photographer as Hollywood portrays us?

Hollywood doesn’t show us slogging around our portfolios, or spending sleepless nights building websites, digging through receipts for the inevitable tax audits, or calling clients who are overdue on paying their invoices. It doesn’t show how many times you are likely to be on the brink of bankruptcy. In short, Hollywood often does a pretty good job of showing the practice of being a photographer, but it never shows the business of being a photographer. It’s hard to be creative when you have no financial stability, so the creation of a fiscal foundation that supports their creative aspirations should be part of every artist’s plan.

There are a few inherent problems with the way photographers begin their careers that contribute to financial difficulties later on.

Most of us begin shooting when we are teenagers, and photography at this early stage is often very gratifying with very little formal training. In this formative phase we get a lot of positive reinforcement for adolescent work that seems very accomplished, original, and creative to us, and the people around us. This is truer than ever with the proliferation of smartphones and social networking. It would be hard for a 17-year-old with 50,000 Instagram followers not to be seduced by the idea that photography might be a pretty easy way to make a living and have fun. There’s a parallel for young musicians who quickly master the three basic “cheat chords” and begin to fantasize about life as a rock star. It’s one thing to impress your friends and family, but as your career progresses it is going to get much, much harder and you may not be prepared for the level of commitment it will ultimately require.

Another factor is that every professional artist starts his/her career as an amateur. Henri Cartier-Bresson was an amateur before he ever became “Cartier-Bresson,” so were Jackson Pollack and John Lennon. Lawyers and accountants don’t start their careers as a hobby. Doctors don’t begin their profession as teenagers by setting the limbs of their friends after accidents for fun, but judging from the application portfolios I see annually, every aspiring teenage photographer has photographed a pretty girl (in a white dress in the woods), or their friend performing a trick on a skateboard.

While all artists start as amateurs, it is also vital that even after we become accomplished pros we still maintain our “profession” as a hobby. We need to continue to innovate and keep our work fresh by doing projects and personal work that don’t earn income. This means that we often find ourselves saying, “Don’t tell anyone, but I’d do this job for free”; as a consequence we often undervalue our skills, underestimate jobs, and undercharge for our work.

Photography is, for the most part, an entrepreneurial profession, but very few university photography programs provide the requisite training for graduates to become successful entrepreneurs. Business professionals love to make fun of artists and photographers for the terrible ways we run our businesses. Very few photographers ever start with a real business plan or any start-up capital to speak of. We are all amateurs until the day when we get a call, usually the friend of a friend, and they want to know if we can shoot something, a wedding, a headshot, or some photos for a website, and we do it. Maybe it goes well, and we have a happy client who refers us to someone else. Then we do another job, and another, and in a year or two we quit our day job, build a website, get some business cards printed, and before we know it we have become professional photographers.

No other business is started like this; there was never a formal business plan, no capitalization, no advertising, no branding, and no market analysis. According to every commonly accepted business practice no photographer should ever succeed.

If you went to a bank and asked for a loan to start a business that would require you to spend thousands of dollars in materials and time, and allowed your clients to pay 90 days after the job was delivered, your application would be stamped “rejected” before you finished shaking the loan officer’s hand. Yet photographers buy thousands of dollars of equipment and materials for jobs on credit cards all the time. We accept credit card debt as a “cost of doing business,” and we routinely advance money to multi-million dollar corporations, ad agencies, and magazine conglomerates at zero interest rates.

And yet, in spite of the odds against us, many of us succeed; we build careers, make enough money to support our families and spend our days doing what we love. We work obscenely hard, but it never feels like work because if it’s all going well you are having too much fun.

It’s Not About the Money, But the Money Does Matter

I doubt that anyone becomes a photographer to get rich and even if that was the goal then they are probably doomed to fail. In my professional practice I have photographed hundreds of very successful business people for Fortune, Forbes, and other publications. Successful business people are a different breed; they compete in a world where money is their way of keeping score. If net profits are up by 10 percent then they are winning, if their stock portfolio drops by a few percentage points they are a failure. If they get a raise or a promotion, it is tangible evidence of their value.

Our successes are measured in exhibitions, books, magazine pages, and memorable images.

A young photographer friend of mine recently sold a personal fine art project to a major publication. He did the project on his own dime; he saved diligently for a year from the money he earned assisting other photographers and shooting weddings on weekends. He had no thoughts of the project being a financial success, and he never even sent it to the magazine; the editors discovered it on his website when they were randomly trolling Instagram for fresh young photographers. The money the magazine paid for the rights to the project was fantastic (he was able to pay off his remaining student loans in a lump payment) but the really exciting part was the prestige of getting 15–20 pages published in one of the world’s premier magazines. The story will launch his career and open up a world of new opportunities. The financial reward is appreciable, but that’s just a side benefit to the body of work he created. He is 23-years-old and his future is very, very bright.

In fact, even when you look at the careers of the few superstar photographers who are billing millions of dollars annually it is important to remember that they didn’t achieve their financial success by being good business people. They got there by being exceptional photographers, by taking every photograph, every assignment, as a creative opportunity. If you look at virtually every great and financially successful photographer from Avedon to Liebovitz you will see that they routinely took on projects that were financially disastrous, but creatively fulfilling. These are the projects (loss leaders in business parlance) that made them inimitable and allowed them to demand top dollar for commercial assignments; advertising, and so on, where the money available is much, much greater.

Why Do We Become Photographers?

Like many photographers of my generation I became a “professional” by accident. I was just a guy who loved getting up every morning and throwing a camera over my shoulder as I walked out the door. Life is a daily adventure and making photographs enhances that adventure; the challenge of being a participatory observer of the world around you puts “skin in the game”. Photography makes life, and your place in the world a little more vibrant, and lot more meaningful.

I hadn’t considered what I’d do after college. I had no plans to make a living as a pro because I thought professional photographers were “hacks”; technicians who just made the pictures that they were paid to take, and my few experiences assisting low-level professional studio photographers only confirmed that impression. My heroes were Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and Walker Evans. None of them worked for magazines, or ad agencies (or so I thought); they were pure artists.

As a student I had done internships at art galleries, so after graduation I got a job at a gallery that showed photography. I loved working at the gallery so I thought I’d become an art dealer and make photographs during my free time purely for art’s sake. When I started shooting exclusively in large format color film my personal projects got too expensive to fund from my salary, and as my job became more demanding I found I had less and less time to pursue my own work. I only became a professional photographer as a more efficient way to finance my addiction to making photographs and carve out more time to pursue my personal work. Being able to deduct the expenses for my personal projects was a welcome side benefit.

The point is that like most photographers, musicians, dancers, and cowboys, I never really cared about the money. The surprising thing was that becoming a professional raised the stakes and meant that I actually had more skin in the game. It gave me access to subject matter and situations that would have been difficult or impossible without the framework of a magazine assignment, and it presented fresh challenges and obstacles that made me a better photographer in my fine-art work. It made the thing that was already the most exciting and rewarding thing in my life even more challenging and fun.

For most successful professionals it’s a two-way street: personal projects nourish your soul and reignite your enthusiasm for your work; they bring fresh ideas to your commercial practice. Clients can sense when you are just “churning it out.” This is a creative field; if you aren’t excited creatively your clients will find someone who is. You became a photographer because you loved making pictures long before anyone paid you to. You became a good photographer by experimenting and trying new things. Keeping that passion alive is necessary for your growth as an artist as well as your financial success. You can’t be a good sales person when you are bored with your own product. When you are excited about your work so is everyone else.

You don’t become a photographer to get rich; you become a photographer to make photographs and satisfy your creative needs. When you stop being a creative photographer you are short-changing the very dreams that made you become a photographer in the first place. Running a business well is simply a way to serve your creative aspirations.

The Changing Scene: When One Door Closes Another One Opens

When I speak to my room full of nervous parents at NYU I have to tell them the same hard truth I will tell you here: It’s not easy, and it never has been. Every generation of photographers has to reinvent both the medium and the business for themselves and for their place in history. The ways that photography is used in the world today is completely different from the way it was used a scant five years ago; it is changing that fast. Reinventing the medium and adapting your business to an ever-changing financial landscape is not easy, but it is absolutely necessary.

This should come as no surprise to anyone conversant with the history of photography. It has always been incumbent on photographers to be adaptable creatures. This is because photography has always been tied to science, technology, and the economic realities of society. Avedon’s reinvention of fashion photography was largely due to the advent of commercially available strobe lighting and the rise of color reproduction in magazines. The introduction of faster films, the invention of the 35 mm camera, and the rise of mass media all presaged Cartier-Bresson’s reinvention of photojournalism. The work of the F.S.A. photographers was directly influenced by the economic realities of the depression, and in fact the work by the F.S.A. photographers was forced to evolve as the United States moved towards joining the Allies during World War II.

With the rise of e-commerce there is more demand for competent/creative studio photographers than ever before. A side benefit is that many e-commerce studio jobs offer a level of financial security that past generations of photographers could only dream of.

Conversely, the decline of print journalism also means that thousands of gifted photojournalists and sports photographers (many of whom had enviable staff positions) have had to transition to wedding photography in order to pay their mortgages. One possible bright spot on the horizon is that as tablet devices replace print magazines photojournalism may be poised to make a comeback (in my opinion).

Video, the rise of the HDSLR, and multimedia production offer new creative and financial possibilities that were unheard of ten years ago.

A recurrent theme among the professionals I have interviewed for this book is that any young photographer who has not embraced video is likely to have a very tough time in their future practice. Video/motion production is here to stay and must be considered part and parcel of the contemporary photographer’s skill set.

In this chapter I’ve interviewed a few photographers who represent a cross-section of traditional areas of specialization: fashion, travel, architecture. They are all very different from each other yet there are a few recurrent themes to their respective successes:

• They have made learning new technology a habitual part of their practice.

• They treat every project as a creative challenge, not a job.

• They are all working far too hard, but they don’t mind it because the work is so fulfilling.

And that’s the best part …

DIANE COOK AND LEN JENSHEL: LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHERS

If there is a better example of two people who have more fully integrated their creative careers, financial success, and love lives in photography, I haven’t found them yet. Len Jenshel and Diane Cook haven’t just made careers as photographers, they’ve made their lives and their marriage about photography.

Nina Subin

After studying with Garry Winogrand, Tod Papageorge, and Joel Meyerowitz at Cooper Union, Len Jenshel quickly established himself as one of the most original photographers of his generation; a pioneer who was reinventing the traditional notions about color photography and its acceptance as a valid form of expression in fine art/documentary photography.

In 1980 he received the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and came to the attention of the New York gallery scene with a solo exhibition at the prestigious Leo Castelli Gallery. He followed this success by publishing his first monograph, Travels in the American West.

Meanwhile Diane Cook graduated from Rutgers University in 1976 where she studied with Larry Fink. After graduation she continued to work on her personal photo projects, which consisted of mainly black and white landscapes, while making her living as a photo editor at Time Inc.

Introduced by mutual friends in 1979, they were married in 1983.

In 1990, Diane left her job as a photo editor at Time Inc. and they began their first collaboration—a long-term landscape project on the volcanic landscape entitled “Hot Spots: America’s Volcanic Landscape,” which was published in 1996. The success of “Hot Spots” cemented their lifelong collaboration in the fine arts—combining color photographs by Len, and black-and-white photographs by Diane—contrasting and joining their two mediums and their individual sensibilities.

In that same year they also began collaborating on magazine assignments. Because most magazines required color photography, Diane began shooting color when they were on assignment. As collaborators they were committed to the idea that there was less difference between the fine-arts world and editorial magazine photography than most people believed—and that the story was the thread between the two. That approach has been a cornerstone to their careers, both as individuals and as a team.

Two photographs from Len and Diane’s book Hot Spots:

America’s Volcanic Landscape

Len Jenshel

Diane Cook

Len Jenshel

Two photographs from Aquarium

Diane Cook

Over the last 30 years they have continued their commercial and creative success, shooting hundreds of assignments for “A-list” magazines like Condé Nast Traveler, the New York Times Magazine, and Fortune to name a few, while also exhibiting their fine-art work worldwide. In 2003 they published their second collaborative book, Aquarium.

In 2006 they got the call that every photographer dreams of; an assignment from National Geographic to shoot the newly erected wall between the United States and Mexico. That assignment was the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the magazine that has continued to the present.

As a longtime friend, and one of their biggest fans, I’ve watched their work develop as both collaborators and individual artists. It would be a futile exercise to try and over-simplify the similarities and differences in their sensibilities here. Suffice it to say that when I look at their collaborative work it’s akin to the experience of listening to two virtuosos playing a duet: The trained ear can hear both the combined melody and the individual players at the same time.

The Wall on the U.S/Mexican Border, for National Geographic

Cook/Jenshel

MJ: So I was especially happy that you guys agreed to let me interview you for this book, because when I ask every freshman class what their ultimate career goal is, about 25 percent of them say that they want to be a National Geographic photographer.

You two are living the dream of many photographers, you get to travel the world and make the pictures you want to make. But you aren’t really the typical National Geographic photographers. Neither of you are hardcore photojournalists, nor do you have the backgrounds in science or anthropology that Geographic traditionally looks for. You’re fine-art landscape photographers. How did you manage to make that switch?

LJ: The editor who brought us into Geographic had seen our books and other stories we’ve done for Condé Nast Traveler, Audubon, Fortune—and many of the other magazines we’ve worked for. Many years later, the Director of Photography told us that we were “the sweet spot between art and journalism.” It was really great to hear it stated that way—it really put things in perspective.

DC: More than any other magazine we have ever worked for, Nat Geo has really told us, “We want what you do—we want your picture.”

LJ: When they called us for our first assignment—on the building of the wall between Mexico and the U.S.—our editor told us, “I don’t want a story on illegal immigration. I don’t want photos of Border Patrol agents, or people scaling the wall—I want you to do landscapes.” So we got to do what we had hoped for—we treated the wall as a piece of sculpture in the landscape—an icon of sorts. It was a story about a cultural landscape.

The Wall on the U.S./Mexican Border, for National Geographic

Cook/Jenshel

Night Gardens for National Geographic

Cook/Jenshel

MJ: That particular story was an assignment, but most of your stories have originated as your ideas that you’ve pitched to the magazine. Tell me about that process. Because Diane has a background as a photo editor I imagine that you have some real insight into how to pitch a story and what the process is like from the editorial side of the table.

LJ: Well the reality is—you don’t just pitch the story once—you really have to pitch it many times during the process of working on a feature for National Geographic—first there’s the pitch meeting to sell the idea, then an interim show, and then the final show and the layout.

MJ: Really? I’ve pitched lots of stories, and there is an art to it, but it’s never been that involved for the stories I’ve pitched.

DC: The initial pitch is short, like a traditional “elevator pitch.” It should be no more than one page long.

LJ: [aside] Did we mention that the best advice we have for young aspiring photographers is to learn how to do an elevator pitch?

DC: It has to be well researched and it has to be a story that is slanted towards your work in particular and you have to make sure the magazine hasn’t done the story before—and, of course, it has to be brilliant and engaging.

LJ: For example, we just got a story approved on “wise trees.” These are historically significant trees, trees that have borne witness to history; like the Emancipation Oak where the Emancipation Proclamation was first read to the slaves, and the apple tree in England where Isaac Newton first witnessed an apple falling from the tree, and thus formulated the theory of gravity.

MJ: Wow, that tree is still there?

LJ: Yes, it’s still there—and still producing apples—though not many.

DC: So the initial pitch has to be short and to the point but you also have to do enough research to be confident that if they are interested you are certain that there’s a significant story there. The first pitch is sent in and we see if they are interested.

If they like the idea, then you really have to do a ton more research and come up with a full proposal—a work plan—a line-by-line list of dates and locations. And if that gets approved, then a budget—an estimate of expenses comes next. Then that goes in for approval—and then you’re on your way.

We look at seasonal weather patterns for every location—so perhaps (for trees) you want to photograph a particular specimen with spring blossoms, one with autumn foliage, etc. We also use tools, like Google Earth, to scout locations and possible vantage points for certain shots, and we use a program called The Photographer’s Ephemeris (http://photoephemeris.com) to predict where and when the sun and moon will be rising and setting, the azimuth, where shadows will fall from surrounding buildings or mountains—at different times of the year. It is an amazing piece of software.

LJ: That program saved us on our “Night Gardens” story—when we were shooting the Italian water garden at Longwood Gardens. We wanted the moon to be centered in a shot above a fountain—and the program enabled us to predict exactly when the moon would be in that exact position.

DC: We also really watch weather patterns. On the “Night Gardens” story we obviously wanted to shoot as much as possible by the full moon so that means you have about four nights a month that are ideal conditions. If it’s raining two of those nights we’ve lost half of our shoot time.

MJ: Are you paid for the time you are researching? The process must be exhaustive. I also imagine that Diane has to be really good at this given her background.

LJ: We share the load, but Diane does have a little more patience for this part of the process. The research is a huge part of the process that most people are totally unaware of but it helps us so much once we are in the field that it’s always time well spent. Yes—Diane is great at research—and I’m the one who gets on the phone and schmoozes and sweet talks the people into giving us ample time to make “great” pictures. How many times have I heard, “Why do you need three days to photograph that—when the local newspaper came by they only needed three minutes?”

Diane Cook

Backyard of Heirloom Rose subdivision, inundated with tumbleweeds, Lancaster, CA, for National Geographic

Cook/Jenshel

DC: When, and if, the editors approve the story, we pack our bags and start shooting. When we feel like the story is about halfway complete we return to New York, process files, look at what we’ve done, and prepare another presentation for the editors in Washington on the progress of the story so far—this is called the “halfway show” or “interim show.”

MJ: Does the direction of the story ever change based on their input from that presentation?

LJ: Sometimes, but it’s usually a change that was good for us, and the story. We did a story on tumbleweeds; it was an assignment from them, not one of our ideas, and it was initially supposed to be a fairly traditional science story about the proliferation of superweeds, specifically Russian thistle in the United States. But after the editors saw our quirky approach to the story the magazine changed the editorial slant of the story to suit some of the more lyrical and humorous photos we were shooting.

DC: After the interim show, the editors meet and decide whether to continue to fund the rest of the project—either a thumbs up or thumbs down. Or they can decide to switch gears, make a large or small change, etc. (to use a sports world term—a halftime adjustment). And finally when the second half is done, we go back to Washington and do a final presentation of the whole project. This is like defending a PhD dissertation—you need to show the entire arc of the story, along with great pictures (obviously), great stories, and facts and humor and charm—nothing less. Is that stressful? You bet!

LJ: But don’t forget, this is a very specific process to National Geographic. As is also the amount of time we have to produce and shoot a story. Most magazines don’t give you nearly as much time to work on a story.

MJ: This is all a far cry from the stereotypical image the average person has of photographers wandering around the world and relying on fortune.

LJ: There’s a great quote from John Szarkowski: “And whether good or bad, luck is the attentive photographer’s best friend, for it defines what might be anticipated next time.”

MJ: Szarkowski is still my favorite writer on photography and that quote is still true. We build photographic “luck” by paying close attention to the world, the same way a gambler builds luck by studying the facial tics of the other players at the table.

MJ: The other reason I really wanted to interview you is because you haven’t just built your careers on photography, you’ve also built a marriage, a business partnership, and a collaborative body of creative work in addition to your solo projects. This is a profession that can be tough on relationships, especially when one of the people in the relationship is traveling all the time. Can you talk a little bit about that? How do you divvy up the responsibilities?

LJ: [laughing] Well, we have no kids, no pets, and all our plants are cacti—so we only have to water them every six weeks or so.

MJ: I’ve known you both for a long time and I’ve seen many bodies of work that each of you have created individually so—to a certain extent—I can separate out the work and see the individual photos that each of you are making. It’s obvious in many cases because Diane still shoots black and white for her personal work but when you are on assignment you both shoot color. How do you actually work it out when you are shooting? I guess what I’m asking is are there times when you see a situation and you know it’s more appropriate for the other partner?

DC: All the time.

LJ: [laughing] Honestly, when I can’t make a photo work I call Diane over, because if it’s not working for me, then I figure it must be a black-and-white photo. And I think the same holds true for Diane. But, don’t forget, there were the exceptions to the rule—like Kathleen Klech of Condé Nast Traveler, who not only encouraged Diane to shoot in black and white but published the black-and-white work.

DC: And just as we were talking earlier about how I might be a little better at the research and preproduction, Len is really amazing when we get into the field. He can talk his way past security guards and get people to let us camp out for hours, or even days, in a location.

When we were doing the tumbleweed story we were driving around and we could see that a particular residential backyard on the other side of a wall was inundated with tumbleweeds, so we drove around and lo and behold, there’s a woman leaving that house and getting into her car. Len jumps out from behind the wheel of our car—while it’s still moving—and runs up to the woman to ask if we can go into her backyard to make some pictures for our story. Meanwhile I’m trying to put on the brakes and stop the car …

LJ: Well of course the woman is mortified because all of her neighbors have cleaned up all the tumbleweeds from their yards and hers is still covered with tumbleweed. She certainly doesn’t want us to shoot it and she’s on her way out for dinner with friends …

DC: [continuing] … but Len talked her into it. So we get into the yard and there are all the tumbleweeds and the wagon, but the light isn’t quite right yet …

LJ: … so Diane and I take turns talking to her and keeping her occupied until the sun gets lower in the sky and then we make the photograph. It’s the double-page opener of the story—and one of our favorites.

MJ: Nice. So we were talking earlier about the difference between photojournalism and fine art and that particular picture seems to be a good segue because you mentioned that it was a homage to the famous William Eggleston photograph of the tricycle on the cover of William Eggleston’s Guide. It’s a very straight-forward photo (so to say), but it also has those layers.

LJ: When I was a much younger photographer I thought the greatest difference between photojournalism and the fine arts was that journalism was overstated and art was understated. Put another way; journalism told a story, though sometimes at the expense of hitting one over the head, while art was better suited toward fiction—and could only suggest a narrative—art being much better at metaphor.

I think of it like this: Art, at its best, is ambiguous and intuitive and instinctive—and asks many more questions than it answers.

With that said, we both came to journalism through the non-traditional back door, we came from the art world. But we wanted to find a way to combine this wonderful notion of storytelling with a bit more subtlety, a bit more ambiguity, but with much more poetry. The real goal for us is to make wonderful photographs—ones that are totally capable of a narrative—but don’t ever need a caption. Imagine that!

MJ: Right, because great photographs have layers of meaning that are created by their inherent ambiguity and when the photograph uses the caption as a crutch all the mystery is taken away. There’s a great quote from Cartier-Bresson: “The anecdote is the enemy of photography.” Traditional photojournalistic captions are often used to reduce the photograph to a single specific meaning, which might be great if you are trying to inform the public. But if the photograph is wonderful the caption can suck all the life and mystery from it, and if it isn’t a great photograph then the caption isn’t going to make it better.

LJ: Agreed! And that’s a great line from Bresson—I did not know that one.

MJ: Actually, case in point, is that we have just related two anecdotes about the stories behind two of your photographs. The purpose of this book is to demystify the lives and careers of professional photographers so I hope the stories do that for the intended audience of young photographers, but there’s no denying that the story of how you researched and planned where the moon would appear in the night-garden shot changes the photograph in the mind of the viewer. The anecdote reveals your artistic process, which is great in this context, but it does make the photograph less mysterious.

LJ: Not really—because having as much information as you can get is only a plus. You can reject that later on—or make a whole different picture you never conceptualized. But knowing exactly where and when the moon will rise can’t hurt—if you know what I mean.

DC: All true, but even with all the research we were still sweating in that garden as we watched the moon come around in its orbit. We were never really sure it was going to do exactly what we expected it to …

MJ: Or if a cloud was going to roll in and completely obscure it …

LJ: And who knows? Maybe that would have made it better … Diane’s favorite expression, “When you’ve got lemons—you make lemonade.”

DC: And then we’d all be sitting here talking about the lucky accident!

MJ: Exactly. So something that you mentioned a while back was very interesting. When you were talking about the “wise trees” pitch I was surprised that you spoke about a story you hadn’t started yet because back in the day we were never allowed to leak stories or show any photographs in advance of publication.

LJ: Yes, that’s all changed, now they want you to post photos from the trip to your Instagram feed. It generates anticipation and helps to market the magazine and create buzz around the project.

MJ: Because your followers are the potential customers/viewers once the story is published.

LJ: Right, it’s amazing, now every publisher wants to know what we are “bringing to the table,” it’s not enough to just make amazing photographs and have a great book concept. They want money, they want us to have traveling exhibitions lined up in advance, and have a deal with a corporate sponsor. The marketing of photography has gotten crazy.

MJ: It’s true, this profession has always been about shameless self-promotion because every client wants to feel that they are getting the best photographer in the world. I know that has been awkward for me personally because sometimes I can have a hard time turning it off.

But social media has taken it to a whole new level. It’s a little insane how many monthly newsletters I get from photographers, how many Facebook posts from ex-students are about the assignment they just did, and how many requests I get to contribute to fund someone’s book project through crowdfunding. I get a little turned off by it, but some people do it very well. When there’s really new work or they’re doing a significant project I’m happy to check out their site or contribute to the book project.

You know it occurs to me that through all of this I have been referring to you as “landscape” photographers, but that’s not true and I’ve actually never thought of you as landscape photographers because the tradition of landscape photography is—if you really look at it—rooted in an almost religious reverence, for the natural world in its most pristine form. Sometimes that happens, like in Diane’s “dunes” project or the volcano pictures. But more often, your work is much more about the scars, or adornment, that humans have left on the natural world.

DC: We’re interested in making photographs that address different aspects of human intervention, boundary, and the control of nature. We make photographs in the documentary tradition, but hopefully we do not make documents. We hope to create a dialogue—one between the two of us—and another between our viewers and us; a dialogue that is intuitive, lyrical, and aims for poetry.

LJ: We love art, but we also love science, and we care deeply about the environment. We love nature, but we’re also intrigued how the altered landscape is a veritable battleground on our planet. National Geographic, Audubon, On Earth (the more journalistic publications) have recognized our passion and let us run with it. All of them have blessed us with some of the most interesting assignments we have had in the last ten years.

Every story is a huge amount of work—yes it sounds like a dream—but we work so very hard on all aspects of the photos and the story. Every story comes with amazing pressure, and incredible challenges to solve. But then—we’ll find ourselves waking up in Iceland or Greenland, in some of our favorite places in the world—and we’ll have to pinch each other, just to make sure we aren’t dreaming.

KRISTIINA WILSON: FASHION PHOTOGRAPHER

For many young photographers a big-time career in fashion photography is the ultimate Hollywood dream. A lifestyle filled with beautiful people, exotic locations, sweet cars, and fat paychecks. While I’m sure there are photographers out there who are living that dream, I haven’t met one yet, and I’ve met some pretty big-time fashion photographers.

To be sure, some of the stereotypes are true. You do get to travel, but what they don’t show in movies is that once you get to Morocco, Cancun, or wherever, you have to get up at 4 a.m. in order to be ready to shoot by dawn. Then in the evening, when all the models, stylists, and editors are at the bar you are in your hotel room on the computer, retouching, estimating, emailing, and negotiating for the next job. Fashion photography in practice is a huge amount of hard work that has to look easy and fun, because that’s the illusion that magazines and advertisers are trying to sell.

More than any other area of specialization fashion photography requires that you are constantly working on creating fresh content. A great landscape or portrait might be able to sit on your website for years, but last year’s fashion is so … “last year.” Maintaining a career as a fashion photographer requires that you are constantly testing, shooting, thinking, and reinventing the wheel.

Being a professional photographer is entrepreneurial by nature, and this ability to “invent ourselves” is one of the primary attractions of the profession. Kristiina is an interesting example of someone who has truly invented herself. She never had a mentor in the traditional sense, and just “made it up as she went along”; an approach that has its pitfalls, but also allows certain photographers to invent their careers without the preconceptions and poor practices they might have inherited from their mentors.

In talking to Kristiina what was immediately apparent was a formidable young woman with a solid plan and strong creative drive. She puts the business first but always has her gaze fixed on a horizon of fresh creative possibilities.

Kristiina Wilson

Kristiina Wilson

MJ: So one thing I think is kind of interesting about your career is that you never assisted for anyone did you? How did you do that?

KW: I just … started! I just decided to do it, and I made a lot of garbage! The other day my assistant and I were cleaning out files and I found one of my early portfolio shoots: I photographed my best friend and my ex-husband as a “pretend couple” at my parents’ house. My assistant and I were laughing: it was really bad.

I supported myself shooting weddings and building websites. People with web-design skills were pretty rare back then so I made a good living as a web designer, that’s how I was able to buy my house. But while I was doing all that I just decided to start as a fashion photographer. I started setting up shoots, testing models, and made it up as I went along.

I didn’t assist for anyone because I wouldn’t have been a good assistant. I can’t work for someone else, I just won’t show up. But I have a killer work ethic, I’ll work 16 hours a day seven days a week for years. Working for myself, doing what I love to do.

So yeah, I just made it up. I had no industry contacts, no mentor, no agent. I’d go to the magazine stand with a pad and pen, look at the masthead [the directory of all the editors and art staff] of the magazines I wanted to work for, copy down their names and cold call them to set up interviews. I’m sure I was really annoying but that was how I did it.

MJ: Well that’s amazing because that’s exactly how I did it as well. Although I usually sent them a promo card a week before I called because I figured that if they liked the promo then they’d take the call or call me back if I got their voicemail.

Another thing that’s interesting is that you don’t have an agent.

KW: I had an agent for a while but I felt that they hardly did anything except take 25 percent of my money. I’ve never found an agent who is willing to work as hard as I do.

I’ll forgo a social life, I’m not interested in going out to clubs, I’d rather be doing my own billings or following up on contacts.

I do have a studio manager who negotiates fees for me because it can get a little tacky if you are doing that yourself.

MJ: I’ve had three agents and two of them were useless; in fact one of them was actually detrimental to my career because many of my established clients didn’t want to deal with her.

But I do have to say that I had one agent that I was very happy to have as a representative of my work. She actually didn’t bring in much new work, but we had an unusual deal because she only dealt with my corporate/advertising clients and she only got a commission on those jobs, and she negotiated better fees. That freed up a lot of time for me to work on my editorial career which paid a lot less but was more fulfilling creatively. I’m not down on agents, but I think you really have to find the right fit and it is a lot more work on your shoulders if you are doing all the promotion, the meetings, the billing, and office work yourself.

KW. Well, yes, but who cares? Again, if you love it, you don’t mind the demands on your time.

MJ: One thing that perplexes me about fashion, and your work in particular, is that you seem to have a lot more latitude about your style from shoot to shoot. What I mean is that within a given story or spread, your work is really consistent. But looking at one story for magazine “A” and another for magazine “B,” they can be very different from each other. You seem to be able to change up your style or execution a lot.

KW: Hmmm, yes and no, there are a lot of fashion photographers like Terry Richardson who only do one thing and then there are other people, Steven Meisel for example, who change it up a lot from shoot to shoot.

Remember that I’m collaborating with the magazine or advertiser so often it’s a “look” that’s been dictated by the client, they’ll give me very specific direction: “white background, soft light, these clothes, this style of make-up, etc.”

But other projects, like the “Paper Doll” shoot, that was all my idea, so in my editorial work I’m trying more and more to push the edges of what I can do and incorporate more of the weirder stuff that’s on my Tumblr page.

Kristiina Wilson

Kristiina Wilson

MJ: So this “Paper Doll” shoot …

KW: I shot the model in the studio and then I had a life-size cutout made and I dragged the cutout all over New York shooting her in different locations …

MJ: And that’s the great thing about certain magazines, I know we have both worked for FLAUNT and I love working for them because they basically just give you ten blank pages and tell you to do anything you want. The creative freedom is fantastic, but then again they are paying you …

KW: Nothing! In fact I spent a couple of thousand dollars of my own money having the life-size cutouts made, assistants, catering, etc. so I lost money on that shoot. That’s the drawback to editorial but I got great portfolio material.

MJ: That’s true and I’ve also lost money on those shoots, but I have to say that of all the magazines I’ve shot for, the shoots I’ve done for FLAUNT in particular have generated the most calls from major advertisers. Unfortunately, because I shoot so little fashion I really didn’t have the portfolio to capitalize on the contacts. But, for instance, I love Ruven Afanador’s fashion work but every story is so different, so creative, that I sometimes wonder how any major advertiser can hire him because I don’t know if they can predict what he’ll do.

KW: I wrestle with that all the time because I have catalog work on my site that I’m proud of, it’s good solid work, but it’s “pretty” and sometimes I think that maybe I should just show the weird stuff that shows what I really want to do. But then I get afraid that I won’t work as much or be able to pay my mortgage. That’s why I started my Tumblr site, it keeps my website as a certain kind of marketing tool to a certain type of client, but the Tumblr page is younger, hipper, and edgier.

For an editorial fashion spread Kristiina had life-size prints made from photos she shot of the model in her studio. Financially, the shoot was a loss but generated great samples for her portfolio and website

Kristiina Wilson

Kristiina Wilson

MJ: Right, I think the value of the website is that when you are up for a certain, specific, kind of job you can send a client to that section. If you are up for a campaign that is all couture, you don’t want the creative director surfing through all the crazy stuff that you have on Tumblr feed.

MJ: Now, I remember that you used to do a lot of stories on spec and then you would sell them to magazines as a package later, do you still do that?

KW: No, that’s something you do when you are starting out and I don’t have to do that anymore. I’m too busy with commissions. I keep an idea book and a file on my computer of things I want to do. When a magazine calls I’ll try to push them towards something I’ve been thinking about.

MJ: Are you doing a lot of advertising?

KW: I do some advertising, but I actually make more money doing editorial.

MJ: What? How are you doing that?

KW: I work a lot for Asian magazines that pay much more than magazines in the States.

MJ: I had no idea. How did you tap that market?

KW: For them New York is an exotic, hip location. It’s amazing how often I shoot in Times Square because for foreign magazines it’s the iconic New York location.

But lately I’ve been shooting more and more in my studio, which is in the same building I live in, so it’s great. I can practically roll out of bed and I’m at work.

The one issue that is kind of interesting about the Asian fashion magazines is that they always want to cast very young models. It can get tricky because so many of the models I shoot are brand new and they don’t have a lot of experience. When we shoot on location I’m putting the model in an environment so I can work around their inexperience a little easier, but when you are working in a more sterile studio context there’s nothing except you, the camera, and the model to make the picture work. Older models know how to work their body and the clothes for the camera, they bring life experience and confidence. The young girls need a lot of coaching and direction.

MJ: Another thing that’s more particular to fashion photography is the idea of the “team,” essentially a crew of people that you regularly work with. How many people are on set with you when you shoot? How did you put together your crew?

KW: It can vary from photographer to photographer. Steven Meisel can have a hundred people on a shoot, not everyone is on set necessarily, but the crew can be huge.

But generally, maybe because I’m a control freak and I want to do everything, my crews are pretty small and I want them to be as small as possible. It’s usually just me, my assistant, then the hair stylist, make-up artist, and fashion stylist. It can vary; if it’s a shoot with a lot of models I might need to add more stylists.

MJ: And you are close to your crew? You work with the same people all the time?

KW: Absolutely. I work with the same two or three people all the time. Some of it is just … who you enjoy hanging out with, and people who have similar tastes. I like a team where I don’t have to give much direction.

MJ: Right, because I used to travel so much I always hire people that are good travel companions. If you have to spend eight hours driving or sitting next to the wrong person on a plane, it can be a huge drain and really affect your ability to perform well on set.

How did you put your team together? With my students who want to break into fashion it seems like this is one of the biggest stumbling blocks.

KW: In the beginning you just work with whoever you can find on Craigslist and is willing to work for free. You go to the modeling agencies and you get the girls who are at the bottom of the list and need pictures. It’s taken a long time, but I have a really solid team now.

MJ: When you estimate a job, how do you bill the team? Who is responsible for what? I guess what I’m asking is … Because I don’t shoot a lot of fashion, when I’ve done fashion shoots, usually the magazine casts the models. And provides the team. Sometimes I use a hair and makeup person I like, but more often the magazine has someone they assign to the shoot.

KW: Because I’m shooting the model, I’m responsible for casting the model. If they are available I’ll also ask my makeup person to come to the casting as well. My makeup artist really looks at the model from a different perspective than I do and her input is invaluable. It gives her ideas for how to approach the makeup because she’s looking at the face and the possibilities with her facial structure. I tend to focus on how the model moves, even as they walk in the room.

If we are doing something tight and more focused on the face, like a beauty shoot or sunglasses, then the makeup artist really has a better idea of how the model is going to look and how to achieve the look we want.

But in truth, these days I rarely meet models in person. We get a digital package from the agency and we cast from that. If we are traveling I like to meet the model because I want to get a feel for whether we’re all going to travel well together and just make sure they’re not crazy!

MJ: I know that might sound like a joke to my readers but it happens. I have a friend who was regularly shooting big spreads for Vogue. They were on a shoot in Mexico and two of the models got in an argument with one of the stylists. In the middle of the night the models jumped on a plane and came back to New York leaving an entire crew in Mexico with no models.

That story aside, I think models often get unfairly stereotyped as stupid or flakey. Because so many of my students are also models I think it’s important to remember that for the most part they are very young women, often straight out of high school, so they might not have the maturity of the other people on the shoot. Actually all the female models I’ve ever worked with have been great. A really good model is a joy and makes me look great as a photographer.

KW: I feel the same way. I’ve never had any bad experiences with models being unprofessional.

MJ: How much do sizes matter? The clothes are made to a fitting model right? But you might be shooting a model who’s proportioned differently …

KW: Yes, the clothes are usually made for runway models, and we might be shooting a print model who isn’t rail thin like a runway model. On big shoots we’ll have a tailor on set who will cut the back of the dress and sew in a stretch panel; it’s the same for celebrity photoshoots.

MJ: And what are you shooting with? What gear?

KW: I use a Canon 1DX.

MJ: Really? That’s a strange choice. That’s the Canon with the superfast 12 frames per second motor drive right?

KW: I shoot a lot for T.J.Maxx, and they like to have a sequence of pictures that they can animate into GIFs so I needed the 12 FPS burst rate.

MJ: And what about your other gear? Lighting, lenses, etc….

KW: I keep it simple. 24–70 zoom, a 135 prime and a 180 mm for beauty. That’s it.

In fact I actually get hired to shoot Polaroids a lot (actually a Fuji Instax), so I’m often on set with nothing but a point and shoot camera loaded with instant film.

MJ: I noticed those photos when I was looking through your website but you are actually doing some more sophisticated things than just using the cameras built in flash.

KW: Right, I slave the studio lights to the little flash that’s built into the Fuji, so even though we are shooting with a point and shoot the lighting is considerably more sophisticated.

Clients hire me to shoot fashion with that camera all the time which is actually kind of strange since it’s so low-res that you can’t see the detail in the clothes. But people love the raw-realness of that camera.

When I shoot for myself I still shoot film, but clients won’t let me shoot film on jobs. I have a hard enough time because I won’t shoot tethered.

MJ: Really?! You don’t shoot tethered? Why not?

KW: If I’m shooting a person, the computer pulls the energy from the set. Everyone is focused on the computer instead of the person who is working. People are looking at what just happened instead of what is happening at that moment.

Kristiina Wilson

MJ: I can understand that. Sometimes when I’m shooting tethered I’ll hear the art director or another person on set say something negative about a photo that is on the computer screen, they might be talking about a lighting issue, but what the subject hears is the negativity, that there’s a problem, and it can have an effect on their confidence. That connection between the photographer and the subject can be quite fragile.

What is it about fashion photography that made you decide to specialize? Do you love fashion?

KW: Actually I’m not interested in fashion at all, but fashion photography was a good fit for me. I think for me it’s about the mix of art and commerce. I have a lot of latitude and freedom because I work in fashion.

MJ: But you aren’t the stereotypical fashion photographer either, you’re very down to earth. I know that things get exaggerated by assistants telling war stories, but there are some pretty crazy prima-donna photographers out there.

KW: Fashion is a strange world because it’s so full of “yes” people and butt kissers, and it’s a party world, but I’m more likely to be at home reading a book with my cat.

I think everyone at that stratosphere level; the Steven Klein, Patrick Demarchelier, Mario Testino level, has some kind of weird reputation. It’s a very gossipy business and photographers at that level are surrounded by so many people kissing their butts that I think anyone would have a hard time maintaining perspective. If you think about it, in order to do the work you have to have a pretty extraordinary level of self-confidence and a really healthy ego. It would be pretty hard not to think, “Oh yeah, I’m all that.”

MJ: So when you’re hired, you have a series of conversations with the art director or the client, and somehow you each communicate the look and feel of the shoot. How does that process work?

KW: I’m not sure if photographers in your field market yourselves, or work this way, but in fashion you’re hired for your editorial portfolio, the cool, edgy stuff, but then if you’re doing catalog or advertising, they need to dumb you down a little, or maybe a lot. There are lots of big, mega-fashion photographers who shoot for Kmart, but that’s not the work they put on their website; that’s their payday for all the great editorial work they’ve done for a loss.

MJ: That’s exactly the way it works for me too. I do tons of ad and corporate work that never makes it onto my site because it’s too dull.

So take me through the process, step by step. You get a phone call or email for a job, like an ad client or a catalog shoot where you can’t necessarily call the shots, then what?

KW: Probably the first thing is to contact my team and make sure everyone is available on the date.

As I said before, you get the job based on the editorial work, but in the case of an ad or catalog the client probably already has a branded look that I have to … not duplicate, but be consistent with. I’ll ask them for some photos of the clothes, jewelry, or whatever we’re shooting. They’ll also send me examples of photographs, or model “looks” that are close to their vision.

Then I go to an idea/inspiration folder on my computer, or do web searches and get my brain working on ideas for the shoot. Then I create a mood board, and that process might go back and forth quite a few times between me and the client depending on the kind of shoot it is

MJ: That is different; we don’t have mood boards for what I do, but it seems to be a big thing in fashion.

KW: It’s a really big deal in fashion; even on editorial shoots the magazine will want to see a mood board, and the rest of the team, stylists, hair, makeup, and fashion will respond to the mood boards, add to them, or maybe create their own.

MJ: And who pays for everyone? What are people getting paid? How much does the model get paid, or the stylist?

KW: On editorial the model gets nothing, they are working for tear sheets.

MJ: Really? Nothing. When I’ve shot with models for magazines they usually got paid a token of a couple hundred bucks by the magazine.

KW: Not anymore; people expect a lot for a little in the fashion world. Although, if I’m shooting for one of my Asian magazines then the models get paid.

Then for the stylists … it depends on the shoot; for editorial it might be little to nothing, for a big ad shoot or catalog it might depend on the terms of usage, how many girls … there are a lot of factors. Fashion stylists get paid for one or two days prep and post time, pulling and returning clothes. If I need a producer or a location scout, that’s another budget item.

MJ: And how do you negotiate all that? It’s so complex …

KW: That’s where the studio manager comes in. I’m never directly negotiating for myself. If it’s really complicated or I feel lost, I have a friend who’s a big agent and I can call her for advice.

MJ: See, that’s where I feel like agents are a huge asset. I think they can have an overview of the market that can help them negotiate a better fee, and they have a different perspective because they are in it for the money. When I get called for a great job that I really want to do—and I’m sure you’ve had the same feeling—I’d practically do it for free because I just want to do it for the fun.

On the other hand I’ve often felt with my agents that sometimes their lack of flexibility has cost me jobs. I might negotiate something; like not budging on my fee, but giving the client an extra year of rights to a shoot, that would make the client feel like I’m willing to work with them. I think you need to find places in the negotiation process where you can be flexible without hurting your profit margin.

You are billing for your studio as well right?

What about your equipment, or post-production Photoshop?

KW: The equipment is included in the studio rental. I don’t charge extra for retouching because it’s been included in my creative fee.

MJ: And you require advances?

KW: Yes, 50 percent in advance.

MJ: That’s good. The thing I think is tricky about advances is that if you are going off for five days on a $40,000 shoot everyone understands that you need an advance because you are going to be incurring huge expenses.

The problem is when you have eight small $5000 shoots because each client thinks, “Really it’s just a little shoot, why do you need an advance?”

KW: I know, I know, that’s exactly the problem because a lot of small assignments drain your working capital more than the big ones. I’ve had to fight hard for advances but it’s in all my contracts.

MJ: And every client signs a contract?

KW: Yes; after my years of shooting weddings I found it was a great way to filter out the people I didn’t want to work with. If they won’t sign a contract I won’t work with them.

MJ: Let me ask you about overhead. You have a studio in your home right? And your employees are full time?

KW: No, I own half a building, I live on one floor and the studio is downstairs, so I have to leave my apartment and actually walk outside to go to the studio. It’s legally a commercial use space, and my apartment is residential. It’s good for legal reasons, but I think it’s also good for my brain. When I’m in the studio I’m at work, and it’s a different mentality from being in my living space.

I have a full-time assistant and a part-time studio manager.

MJ: And as regular employees you are paying them on the books, social security, federal withholding, all that good stuff. So you have all your other expenses, insurance, accountant, lawyer … Do you have a sense of what your yearly operating expenses are?

KW: Including the mortgage on the studio it’s almost 200,000.

MJ: That’s a significant nut, and the problem is that when you go to the dentist and you are charged $250 for a cleaning no one assumes that all that money is going into the dentist’s pocket but when you’re a photographer and you are charging $10,000 per day …

KW: Hah, I know! It’s so annoying, people think you just get to pocket that money!

MJ: Right; depending on how your business is set up (whether you have your own studio, employees, etc.) I figure you get to keep $1000–3000 that you actually get to live on, pay your rent, food, car insurance, etc.

The overhead is intense. Do you feel you need all that overhead? How many days are you actually shooting in your studio?

KW: Three or four.

MJ: That’s a lot! That’s an awful lot. When do you have time to do pre-production and post?

KW: At night! [Laughing.] Like I said, I work all the time, I have no life! Yesterday I shot for eight hours and spent hours doing post while I ate dinner in front of the computer.

I think the big misconception is that people think I spend most of my time shooting but I think I spend 80 percent of my time at a desk: writing estimates, making mood boards, billing, bookkeeping. Getting to shoot is the reward for all the other hard work I do.

Kristiina at work on rooftop in New York, shot from a drone

Kristiina Wilson

BRYAN DENTON: PHOTOJOURNALIST

http://bryandenton.photoshelter.com

Imagine arriving in New York as a college freshman in the fall of 2001. You’re an excited 18-year-old, moving into your dorm room, making new friends, and getting to know your professors. Then, less than two weeks after orientation, your new home becomes the epicenter of a global conflict. For two weeks a solid column of smoke and ash rises from the cityscape to remind you that your country has just been attacked by an enemy you didn’t know existed. An enemy so full of hate that they would gladly die to kill you and your countrymen.

Many young men and woman with revenge in their hearts signed up for a war(s) that was supposed to be quick and easy. Bryan Denton’s instincts led him to take a different path. His impulse was to try and understand the cultural divide between the Western and the Arab worlds that led to the conflict.

Bryan is now an award-winning freelance photographer who has made his home in Beirut, Lebanon since 2006. He is a frequent contributor to the New York Times as well as shooting assignments throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Afghanistan for TIME, Newsweek, Stern, the Wall Street Journal, Vanity Fair Italy, Der Spiegel, Monocle, and Human Rights Watch.

The images he’s produced in his career are not simple photojournalism: they are complex documents of our time that both inform us in the present, and serve the future as traces of our unique place and time in history; images made with a discerning lens and the pure truth of light itself. Of the thousands of conflict journalists roaming the world looking for adventure and bang-bang, Bryan’s work is distinct; in every photograph the viewer is subtly reminded that any man who is holding a gun (on any side of the conflict) has been driven to do so because of deeply held beliefs. Whether it is a U.S. marine manning a remote outpost in Afghanistan, or a boat full of Syrian refugees, every single person in every single image is rendered with dignity and compassion. Bryan’s work reminds us that every human, every culture, and every belief has a rich story to be told, if we would only listen with our hearts.

At the time of this writing Bryan was busy covering Kurdish refugees on the Syrian/Turkish border as they came under artillery fire from ISIS militants. What follows below is a series of email exchanges as he (somehow) found the time to answer my questions.

Bryan Denton

MJ: So of all the careers in photography, photojournalism is the most baffling to me. I can understand that a photojournalist can get hired to shoot an event, but the kind of stuff you do, especially the conflict journalism, how do you get started? Do you just jump on a plane to the nearest war zone? How do you sell work, and get assignments? How do you make a living at it?

BD: To be honest, I’m not 100 percent sure how I got to this point. It certainly wasn’t a linear path, which is what most graduating students are looking for, and to make matters more complicated, the photojournalism industry, in terms of its economics, that I broke into in the mid-2000s has been extensively disrupted by technology since.

I began focusing on photojournalism in university, but more than that, I was focused on the Middle East, which I spent a great deal of my elective credits at NYU studying. When I graduated, photojournalism as a general field was not really what I was interested in, but more specifically telling stories photographically in the Arab world. I knew that in order to make that happen, I had to get there, and I thought about it in fairly black and white terms. I could either stay in New York, where much of the magazine and agency world had their main offices, and try to survive in an expensive city in the hope that somebody would one day send me abroad. My thought process was that why be poor and struggling in NYC doing something I ultimately wasn’t interested in when I could be poor and struggling where I hoped to end up? That was the initial rationalization that got me out the door.

Benghazi, Libya, 2011: A young woman cries and hugs her father, a defecting Libyan soldier who is staying in Benghazi, before boarding a ferry for evacuation to Tunis.

Bryan Denton

2011, Tripoli, Libya. Libyan rebels battled cells of Qaddafi loyalists in the Souk al-Thalatha district, near the front gates of Bab al-Azizia, Gaddafi’s sprawling compound, in Tripoli as rebels fought to capture the city.

Bryan Denton

I initially moved back to Jordan, where I had studied abroad, and had some friends. I had also worked for a small English-language magazine published in Amman while I was a student, so figured I could use that as an initial way to keep busy. At that time I was making about $75 per story, so basically nothing, and I wasn’t sure how one went about getting introduced or seen by larger publications or agencies. This is one thing that NYU didn’t prepare me for at all was how the business of photography itself worked. Amman was a boring journalistic wasteland in the middle of a region that was quite covered and over-saturated with freelancers, so in a way I had the place to myself. This made it a great place to start, but one that I grew out of fairly quickly.

My first break came though from the New York Times, who I work primarily for today. In 2005, before Facebook really took off, there was a social networking site for photojournalists called Lightstalkers, which was started by photographer and now Facebook staffer Teru Kuwayama. I had no personal website at the time, but I did have a Lightstalkers profile, because many editors were also part of the community, and used it to locate freelancers for assignments. Beth Flynn, then the Foreign Picture Editor at the New York Times sent me an email out of the blue after finding me on the site, and asked if I was available to shoot an assignment in Amman. It was a small piece for the Education section on a new private school being built by the king. Not A1 material obviously. This would be the first assignment that I had ever had from an American publication, and it would come to define my career in many ways, and it all came out of luck of the draw so to speak. Without Lightstalkers, they never would have found me.

That same night, coincidentally, there was a terrorist attack in Jordan on several hotels, and I filed my first news images to the paper as well. They weren’t that great, but it started my conversation with them. Lightstalkers and social media also alerted editors at World Picture News, a now defunct NYC based photo agency, that I was in Amman, and I became a contributor with them as well. While I never sold much through them, this initial relationship with an agency gave me a bit of exposure to editors, as I continued to work.

Over the next six months after my first contact with the NYT, I did two or three assignments probably, including the funeral of Abu Musa’ab al Zarqawi, who was from Jordan. These assignments were paltry in terms of compensation. The New York Times hasn’t changed its international day rate of $250 per day, in quite some time, so I had to find additional work. I ended up working part time as a photo editor for a startup magazine in Amman to make rent, which was a really valuable experience because it taught me a bit about how the pie gets made. It also provided a steady stream of extra local work because I was able to freelance for them as well. All told, I was still barely surviving financially off of what I was making, probably $700–1000 per month, but I was making it work.

My first big break came during the war in Lebanon in 2006. I was at my desk at the photo-editing job when the news broke that Hezbollah had captured several Israeli soldiers, and I immediately sent a note to Beth at the New York Times saying that I was thinking of going. At the time, I think I had about $300 available on my one credit card, and maybe 200 in cash. Not enough to cover a war in Lebanon, but I had no idea at the time because I’d never covered a war before. I also expected Beth to write me back and say “sorry, we’re sending João Silva, Tyler Hicks” or someone else, but to my surprise, she said “you’re hired, get up there.”

So I went. I borrowed money from my parents and had them send it Western Union Amman after I spent my last cash on a flight that got canceled when Israel struck the airport and I had to then travel overland. I called my credit card company and bullshitted them into extending my credit limit by $4000 at insane interest rates in order to fund the trip. I had no real playbook to go off of and didn’t want to seem like too much of an amateur with the Times, so didn’t ask for too much advice from them, though I probably should have. Beth, who I’ve always viewed as my patron saint of photography, ended up keeping me on assignment for the duration of the war. 42 days. I didn’t cover the front-page news, but mainly red-shirted in Beirut itself, trying to pick up the smaller enterprise assignments and provide coverage of the air war in Beirut. I also got to meet and start learning from Tyler Hicks, João Silva, and Lynsey Addario during this trip—relationships that have since become close friendships in the years that have passed. Rather than looking at it as a financial success, which in many ways it was—I was able to buy equipment, move to Lebanon, and start working more functionally—it was a huge learning opportunity for me and one that I was lucky to have been given. Without it, I don’t think my career would have been the same. I visited New York shortly after the Lebanon war and went to the NYT offices for the first time to meet Beth, and she asked if I would be interested in a more consistent stringing arrangement that would have me based in Lebanon. There was no promise that the work would continue, no contract, but she said she wanted me to work with Bobby Worth, the new bureau chief who would be arriving in the next year. I was over the moon and felt like I’d made it. This filled me with perhaps too much confidence than I needed at that time—enough to make me feel like I was secure in the job and didn’t have to push myself as much as I should have.

With all that said, that was just a foot in the first door of a never-ending number of doors. That’s photojournalism. Beth was soon promoted within the NY Times and Patrick Witty, who went on to TIME, and now is the DoP (Director of Photography) at Wired magazine, would replace her, and didn’t have the same enthusiasm for developing me as a young photographer with NYT resources as Beth did. That’s not me saying anything disparaging about Patrick. We are friends, and I love his work and eye as an editor. It’s one of the most sensitive in the business, and he’s an incredible photographer himself. Every editor usually tries to make their mark on the paper and wants to do so with photographers who fit their vision. At the time it was frustrating but it taught me an important set of lessons. I realized that I would have to diversify my client base.

As a result, I started pushing for new clients in the region and abroad. This was also a relatively calm time in Lebanon and the Middle East outside of Iraq. Not much was happening in the news. I started doing lots of day work for The National, a broadsheet newspaper in Abu Dhabi that was paying well, albeit for fairly dry work—travel, real estate, and business section type stuff. I also worked for many of the region’s airlines’ inflight magazines. All told, 2009 was a great year financially for me, but it wasn’t very stimulating, and I was getting bored—wondering if this was what I was going to be here for, then I might as well go home.

The second “start” to my career came out of this dissatisfaction with the work I was doing, and in the fall of 2009, I decided to start covering the war in Afghanistan, which the US was increasing surging forces into. The prospect of which was frightening. I’d covered some clashes and unrest in Lebanon, but not conventional military operations in the 3.5 years that I’d been in the Middle East. I’d also never really covered American soldiers, especially within the context of the US military embed. I also didn’t have a publication that was paying me to go. I knew though that I needed to do something that I was interested in so I invested in better body armor, and started to make inroads with the military. More importantly, through Lynsey Addario, I was also introduced to Corbis—one of the world’s largest photo agencies, and was given the opportunity to join as a contributor. Up until then I’d been with boutique agencies that gave me a press pass, but weren’t selling that many images anymore, mainly because their prices were high and their reach was minimal.

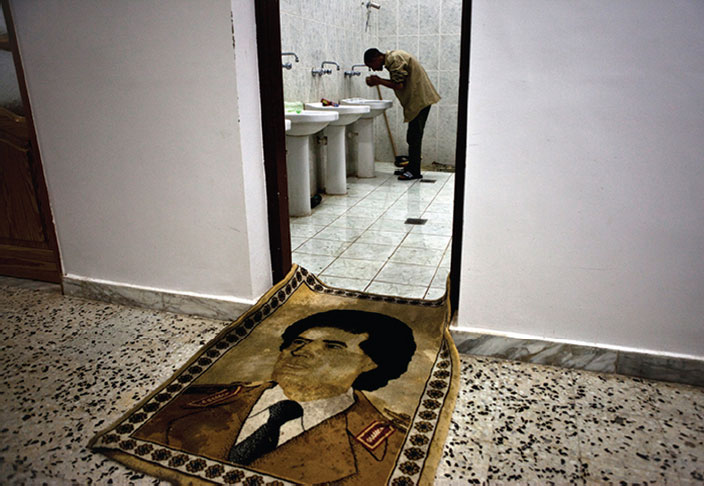

A captured Qadafi forces fighter washes before prayer at a detention facility in Misurata, Tuesday. A wall tapestry of Col. Qadafi has been placed as a door mat for those entering and exiting the restroom—a serious insult in Arab culture.

Credit Line: Bryan Denton

I covered Afghanistan for most of 2010 and early 2011, until Libya exploded. I had still been doing work for the NY Times a fair amount, and Patrick left for TIME and was replaced by David Furst. I initially went to Libya on my own, with no assignment, but with a commitment from Corbis to pay for my satellite transmission fees—a huge favor from them, as the transmission costs are quite expensive. This would be the last time that I would embark on covering a war without an assignment. I picked up work there fairly quickly from my client in Abu Dhabi, but the extreme violence of the place, and that which has marked many of the wars in the region, left me questioning my decision to cover it without more support or an assignment. The potential costs just seemed too high. Since then, I have made the decision not to cover any highly kinetic, frontline stories without an assignment from a publication I trust. I will still travel to places that are considered unstable or dodgy to do personal work, but I draw the line at battlefields. That said, I don’t know if I would have my career if I had always had that rule, and there are many more resources now for freelancers, including insurance plans, and medical training courses that were not available when I started.