6

Why Headlines Matter

In newspapers and magazines, headlines serve the same purpose as a store’s logo on its window, wall, or door: They are meant not only to inform you of what’s inside, but to lure you in. A person walking down the street will take no more than a few seconds to read the store sign and glance in the window before deciding whether to go in. So it is with headlines. The main headline, the top line, is the store sign. Any kind of readout—a second line or deck—is its window display.

We could call this The First Rule Of Headlines: You have two seconds to get the readers interested. As we said in Chapter 2, headlines must be clear. They can be clever, too. But clarity must come first.

Headlines on the Internet do the same—inform and draw the reader into the story. But they must do much more, and that is why headlines matter more on the net than in any other medium. Headlines need to contain keywords that will turn up in search engine results and in social media searches. On a blog and on many news websites, headlines not only appear at the top of stories. Recent headlines often also appear along the left-hand or right-hand side of the page to keep them instantly accessible to the reader. These headlines continue to tell and sell the story, reminding readers what they might have missed.

How Readers Find Blog Posts

Some readers will check your blog every day to see what’s new. They will be your family and friends, at least at the start. Most won’t. So to build an audience, you need to know how people find things on the Web and how to draw them to your stories.

You’ll get the vast majority of your new readers through social media (see Chapter 12, “Building Your Blogging Brand”), and from Google and other search engines. Readers scan web pages, surf from one site to another, and go to search engines when a topic they want to know more about pops into their heads. From various studies of Web use, here’s what we know:

- About three-quarters of readers use search engines to find news and commentary. They already know the topic they are interested in, and they are looking for information and perspective.

- Two out of three readers come to a news website without ever going to the front page. They get to the page that interests them either through a search or by clicking on a link they’ve found on social media.

- The average time an Internet user spends on a page is less than a minute; the average time an Internet user spends on a website is about three minutes.

See why headlines matter? To get readers to click their way through to your blog posts, your headlines—your store signs—need clarity and pizzazz.

Writing Headlines for the Reader

- Build off the main point. This isn’t always in the lede. Blog posts sometimes begin with introductory, scene-setting, or contextual material. The headline should cut to the chase. Give the news or purpose.

- Don’t repeat the wording of the lede. If the first paragraph of your blog post reads, “The European Union has gone too far in regulating perfumes,” don’t write a headline that says “New EU Perfume Regulations Go Too Far.” Try something like: “New EU Perfume Regs Smell Too Strong.”

- Use the present tense. The present tense gives headlines immediacy and freshness. Your headline the day after the presidential election would be “Obama wins second term,” not “Obama won second term.” In English grammar, as well as the grammar of many other languages, this is known as the “historical present.” You use it frequently in conversation: “So I’m sitting in my office the other day …”

- Cut to the bones. Headlines omit any form of the verb “to be” and any form of article. Note that the example of a bad headline above did not read “The Problem Is The New EU Perfume Regulations Go Too Far” (that would have made it even worse). Omitting forms of “to be” and articles such as the, a, and an save valuable headline space.

- Use commas instead of “and.” Another way to save space: “Festival to Feature The National, Lorde, Bruno Mars.”

- Use punctuation sparingly. Never end a headline with an exclamation point. A headline, by virtue of being in a larger font size, is already a typographical exclamation. Using an exclamation point at the end of a headline is like shouting at your reader.

-

Choose a consistent style. Decide whether you want the headlines on your site to be “upstyle,” capitalizing each word except prepositions, or “downstyle,” in which only the first word and proper nouns are capitalized. Consistency is key.

-

Upstyle:

U.S. Warns Afghans Not to Form “Parallel Government”

-

Downstyle:

U.S. warns Afghans not to form “parallel government”

Whichever style you choose is a matter of taste. One is not considered more readable than the other, in print or on the Web. nytimes.com uses upstyle, while theguardian.com uses down-style.

-

- Start with the subject. Headlines typically follow a noun-verb-object construction. This is the active voice—the construction of the famous news lesson: “Man bites dog.” “Dog is bitten” wouldn’t make much of a story. Dogs bite each other every day. “Dog is bitten by man” eats up a lot of space and backs into the point. Man bites dog? Well, that doesn’t happen every day—which is why this story makes news.

Writing Headlines for Search Engines and Social Media

- Include keywords in every headline. If you have written a blog post about a recipe that uses cilantro as a spice in crab cakes, your most obvious keywords would be “cilantro,” “recipe,” and “crab cakes.” By including those keywords in a headline (“Chef François Uses Cilantro in His Famous Crab Cakes Recipe”), your blog post will have a much better chance of appearing at the top of the results when a web user searches “recipe crab cakes cilantro.” The use of keywords in blog headlines is essential. It is how search engines find them. Search engines work, in part, by constantly combing the web for text and building indexes of the words they find. The better you can match up the keywords of your headline and text to the words Web users submit to search engines, the better chance your post will have of appearing near the top of the results.

- Write headlines that can stand on their own. In a newspaper, the headline sits atop the story. The web is different. Often, on a web page or a blog, the headline stands by itself—the reader needs to click through to read the story. This, obviously, places more importance on headlines. If they aren’t good—and enticing— you won’t get readers to click through to your article. We’ve already mentioned another reason to write headlines that can stand on their own: In most blogging software, the headlines and only the headlines from your previous half dozen or so posts will appear in a column on the left-hand or right-hand side of the page. Good headlines entice your readers to catch up with older posts.

- Place the most emphasis on nouns. Yes, active voice demands strong verbs. But online, the “who” or “where” can be the most important elements of the headline because, once again, of those search engines. In the crab cake headline above, the emphasis is on the nouns (cilantro, Chef François, and crab cakes), not the verb (uses). On the web, think of the headline as a label for the blog post. Remember those storefronts?

-

If space is an issue, skip the verb. Verbless headlines sometimes can be more effective. In print (magazines, alternative newspapers, daily newspapers), such headlines often appear over feature stories, editorials, op-ed columns, advice columns—anything that isn’t straight news. Below are headlines taken from nytimes.com on a Monday morning in mid-summer 2014. Note the difference between the news story headlines and the blog post headlines.

News story headlines

- Ukraine Military Finds Its Footing Against Pro-Russian Rebels

- Top Iraqi General Killed in Mortar Attack

- Britain to Investigate Allegations of Sexual Abuse Cover-Up Decades Ago

- Eduard Shevardnadze, Soviet Foreign Minister Under Gorbachev, Is Dead at 86

- Still-Divided Washington Readies for Start of Recreational Marijuana Sales

- Severe Storm Damages Homes, Hurts 6 in W. Michigan

- Obama Weighs Steps to Cover Contraception

Blog post headlines

- 50 Ways to Love Your Quinoa

- Learning “Lear”: A King’s Gotta Eat

- “The Leftovers” Recap: Laws of Human Nature, Interrupted—or, The Case of the Disappearing Bagel

- Book Review Podcast: Hillary Rodham Clinton’s “Hard Choices”

- They Have Seen the Future of the Internet, and It Is Dark

- Rescuing an iPod With a Fishing Knife

- What’s News in Washington: Immigration Fireworks

Which headlines are you most likely to click on? Our guess is that you would click on the news story headlines only if the news is of interest to you. The blog post headlines, on the other hand, are written to tantalize you into clicking. I wonder what it means that “a king’s gotta eat” in learning the play King Lear? (Click.) Hey, I watched the last episode of The Leftovers. What does this writer have to say about it? (Click.) How can a fishing knife rescue an iPod? (Click.) Note, however, the importance of the noun in all three cases. You’d be less likely to click on “A King’s Gotta Eat,” without Lear. You’ve got to have iPod and The Leftovers for either head to work.

- Use question headlines sparingly. Headlines that ask a question don’t work on news stories—after all, the job of a news story is to answer questions. But for a more reflective blog post, the question mark can draw readers. Take this example from a post about the clinical trials for a medication to fight breast cancer. The headline “How Effective is Tamoxifen in Pre-Menopausal Women?” works well because it identifies a drug widely used in treating breast cancer and discusses the results of the latest medical research. Questions can also work atop posts directed at the reader. A financial advice blog post about the advantages and disadvantages of different types of student loans might be topped with the headline “What is The Best Student Loan Package for You?” It limits audience, but it also targets audience.

- Limit headlines to 10 words or less. Google, the king of the search engines, displays only the first 60 characters (letters, spaces, punctuation) of a headline in its search results. You want the headline to appear in full in search engine results—you wrote it to entice readers. So why sabotage yourself? Here is a headline, 59 characters long, as it would appear in a Google search result: “The Most Important Thing You Need to Know Before You Go to University is.” You may think that is a clever way to get the reader to click. It isn’t. Without the most important piece of information, the reader will ignore your partial headline, and find one that gives the answer.

- Keywords alone do not make a headline. Don’t turn yourself inside out to game the system of web algorithms. In the end, humans decide whether and what to click on. Search engines use far more than headlines to rank results. The people who write the algorithms that run search engines became wise to the piling-up-keywords ploy a long time ago. In the end, a headline still must impart information and intrigue a reader. Keywords can help you do that; they can’t replace news judgment and intelligence.

Bob Trott

“Mom was right: You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression”

Bob Trott, a former Associated Press reporter, works as an editor and web producer of the “Money” channel at Microsoft’s msn.com, ranked by the news analytics company Alexa as one the 50 most popular websites worldwide.

Bob Trott

What makes a good online headline, and how is it different from a print headline?

Online and print headlines are similar in that they’ve got to grab the reader’s attention and sum up the story in just a few words. Obviously it’s still the first impression you’re making on the reader. The headlines are different because once you’re holding a newspaper, the article is right there under the story. Online, it’s behind the link, so you’ve got to make readers want to go beyond the link. Nowadays, the headline has to be more of an enticement that “you need to know what this article says” instead of “here is what this article is about.” That has always been important, I think, but it’s more so now.

What are the worst sins a headline writer can commit?

A flat headline that says absolutely nothing. I have punched up many a headline along the lines of, “New bank regulations proposed.” I also am not a huge fan of question headlines, they’re cheap and easy, but sometimes (particularly in personal finance, I find) they can’t be avoided. And readers respond to them, so perhaps I shouldn’t complain. Also, it’s key with online headlines to not give away the punch line. If you read a headline that says “George Springer named AL MVP,” you know all you need to about that story. Why click? But a “Surprise pick for AL MVP” headline … well, you’re going to click on that.

Do you have a mental process for writing a headline? Do you start with a keyword and build from there? Do you start with a subject and verb? Do you consider nouns (who, where, what) more important than verbs?

With the importance on headlines, particularly if we have articles linked on the msn.com portal, we use keywords and phrases that were tied to our Bing search goals as much as possible. “Retirement planning” is one phrase I’ve worked into more than one headline. Optimizing for search is obviously a concern in any online shop. Same with social media. They’re pretty much audiences you have to write to. I start off by summarizing the story to myself, then trying to narrow down the information to something that: (1) is interesting; (2) makes sense and is coherent as a headline; and (3) could (I hope) be unusual.

How long is too long for an online headline? What’s the maximum number of words or characters?

We used to have a strict 35-character count, spaces included, to keep headlines on one line and to make it easier for the home page to run them, to fit easily within our real estate on msn.com. Lately, though, we have let go of that and occasionally we run headlines that spill over onto line two. That said, I still think shorter is better. If it reads like a complete sentence, you’ve probably written too much.

What guidelines and tips would you give young journalists about writing headlines for the Web?

Mom was right: You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression. There are figures out there somewhere along the lines of 8 of 10 people read a headline, and only two of those click through to read the article. And since online headlines often stand alone, with no image or video or other content, those few words are usually all you’ve got to entice the reader to the entire piece.

Writing Decks

Sometimes two headlines complement one another. The main head (also called the first deck) gives the basics and pulls the reader in. The secondary head or deck expands on the first deck but without repeating words or ideas.

Such multiple deck headlines were the norm until well into the twentieth century. Some papers, magazines, and websites—such as the New York Times—still regularly use them.

On the net, decks are less common. They’re not summaries, which we’ll talk about below. But they do give more information.

When the Titanic sank, 102 years ago, the front page of the New York Times on April 16, 1912 offered up no fewer than 18 decks below the main headline to give the news. These included: “Biggest Liner Plunges to Bottom at 2:20 a.m.,” “Rescuers There Too Late,” “Except to Pick Up the Few Hundred Who Took to the Lifeboats,” and “Women and Children First.”

Headline writers today are lucky to get a second deck to tell the story. It’s important, though, to know how second decks work with the main headline. A few examples should help.

These are from Time magazine and its website, time.com. The site makes excellent use of decks, which, in the case of secondary decks, today sometimes are also called readouts.

Two examples from time.com:

| Head: | El Niño Likely to Hit This Summer |

| Deck: | That could mean fewer destructive hurricanes on the East Coast |

| Head: | Obama’s New Drug Policy Looks Like the Old One |

| Deck: | A new emphasis on treatment and addiction, but no change on marijuana |

A few guidelines for writing decks:

- Don’t repeat the headline. A deck is a supplement to the headline. It should add information.

- Keep the deck short. Don’t write decks any longer than 200 characters. Less is better.

- Never repeat the same words in the main headline and deck. The two examples above follow this rule.

- Dig deep into the article for material. You don’t have to write a deck based on the first paragraph or two of the article. Go deeper and find an interesting fact or angle that draws readers.

- Decks are always downstyle. Even if the main headline is up-style.

Writing Meta Descriptions (Warning: HTML Ahead)

Even if you use blogging software that allows you to make changes to your blog’s and blog posts’ HTML tags, learning the basics of HTML will allow you to control what Web surfers see when your blog or one of your blog posts comes up as a search engine result.

If you don’t use metadata tags, most search engines will instead display the first 160 or so characters of the article. This can be problematic. Here are some examples:

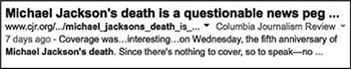

Here is a blog post from The Kicker blog on the website of the Columbia Journalism Review.

Compare the first paragraph of this story to the Google search result below.

(© 2014 Columbia Journalism Review. Reprinted by Permission)

Here is the Google search result for the CJR blog post. Notice that it cuts off the second sentence of the article when the maximum of 160 characters is reached.

Note the second sentence is cut off. Google search results have a maximum of 160 characters.

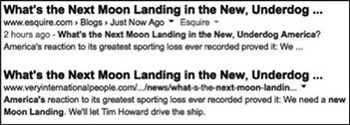

Here’s a post from the website of Esquire magazine, from a news blog called Just Now Ago.

The deck above this story and the first paragraph are different.

(By Permission of Esquire Magazine © The Hearst Corporation)

Here are the first two Google search results for the esquire. com blog post.

The second Google result includes the deck because the Web editors added HTML metadata.

(Google is a Registered Trademark of Google INC., Used with Permission)

Notice that the first result, in the text under the headline, includes the headline (again!) and the first dozen words of the deck. The second result, from a website that picked up and used the esquire.com post, includes the exact text deck below the headline and the URL.

That’s because the producers at the second website used HTML metadata so that the deck would appear in the Google search result— and the producers at esquire.com didn’t. Metadata means “data about data,” and there are simple HTML tags you can use to have search engines display what you want them to display in the search results.

If you go into the HTML of your blog software, you can add, usually beneath the <title> tag, a meta tag. It will look like this:

<meta name=“description” content=“whatever content you want to appear in the search result”>

w3schools.com, a website that offers free HTML tutorials, has a useful meta tag tutorial at www.w3schools.com/tags/tag_meta.asp.

In WordPress, you don’t even need to use HTML to add metadata. All you need to do is add a metadata plug-in, activate it, and type your metadata into the text box provided. It’s a bit more complicated in Google’s Blogger software, but if you do a search for “Google Blogger meta tags,” you’ll find some excellent tutorials that will show you how to add metadata.

Writing Chapter Breaks

Chapter breaks—also known as subheds—are small headlines placed at intervals through the text of an article. They can be used in any long post, but they are particularly useful in instructional blog posts. If you’re writing a post on how to build a birdhouse, each step could have its own subhed.

You should also use subheds, or chapter breaks, in a post that covers more than one topic. If you’re writing a blog that offers advice in response to questions from readers, each new topic should start with a subhed.

These small headlines in the body of text serve several purposes: they help the reader move more efficiently through the text by providing signposts; they add “white space”—empty space above, below, and to the sides of the subhed—that breaks up blocks of text to make them easier to read; and they help you organize your writing. Try writing your subheds before you write your post and you’ll see.

A few quick guidelines for writing chapter breaks:

- Subheds should summarize what’s to come. So for that birdhouse guide, the first subhed might read “Choose a birdhouse plan.”

- Make the font size 18 point. You don’t want your chapter breaks to be close to the same size as the main headline at the top of the page, but you do want them to be slightly larger than the body text. Put chapter breaks in downstyle.

- Use parallel construction. For example, you could start each subhed with an active verb. If the first subhed for the birdhouse is “Choose a birdhouse plan,” the next two, to be parallel, might be “Gather your materials” and “Measure the wood and mark where you will cut.” Or the first three subheds could be: “Plan,” “Materials Needed,” and “Measure.” Either way, all the chapter breaks should have the same grammatical format.

- Avoid cute—be clear and complete. Resist the temptation to use “For the birds” or “A wing and a prayer” or any other ghastly avian puns as subheds in your how-to-build-a-birdhouse post. Not only are they useless to the reader; they confuse.

Discussion

- What type of headline makes you more likely to read the article— a headline that provides factual information (“Government Announces New Low-Interest Student Loan Program”) or a headline without a verb that tries to tease you into reading the article (“The Cats of Des Moines”)? Explain why.

- When you use a search engine to find articles on a topic, how many pages of search results are you likely to scan?

- What do you find most difficult about writing headlines?

- Are posts on Twitter more like headlines or decks? What about posts on Facebook? How are they different from each other?

Exercise

The blog post below was published by one of this book’s authors, Mark Leccese, in his media criticism blog on boston.com in early 2013.

Write a headline, a deck, and a meta description for this blog post. Make sure to include at least one search engine keyword (a word that you believe potential readers will use in their search engine query) in the headline, which should be no longer than 8–10 words. Keep the deck to no longer than 200 characters and the meta description to fewer characters than that.

Reminder: a meta description is the words you want to appear in search results beneath the main headline. For example, for a story about the world’s largest pumpkin, the headline could be “One ton pumpkin sets world record” and the meta description could be “A Northern California man grew a pumpkin that weighed in at 2,058 pounds at yesterday’s Safeway World Championship Pumpkin Weigh-off.”

Main Hed:___________________________________________

Deck:______________________________________________

Meta Description:_____________________________________

In a little-noticed action just after Thanksgiving, the Federal Communications Commission opened the door for hundreds and hundreds of community groups and nonprofit organizations to start hyperlocal radio stations.

Until its November decision, the FCC had prohibited low-power FM stations in urban areas. That’s why there aren’t any in the Boston area. But let’s imagine a low-power FM station in Waltham, a city of 61,000.

Think of the potential for community journalism.

Waltham had a daily newspaper, the News Tribune, until 2010, when GateHouse Media cut the paper to a twice-a-week publication. A year later, GateHouse turned the paper into a weekly. Two years ago patch.com launched a news and features website in Waltham with a full-time staff of one: the editor.

GateHouse, headquartered in Fairport, New York, owns hundreds of newspapers in 21 different states. Patch, a division of AOL Inc., is headquartered in New York, New York and owns and runs more than 850 hyperlocal websites across the U.S.

A hyperlocal radio station in Waltham with a 100-watt transmitter in could reach every corner of the city. The station could use volunteers to cover School Committee and City Council meetings, the Mayor’s office, and all the other community events that used to be covered by the local newspapers.

In addition to news, the station could program call-in talk shows about local issues, shows featuring local music and musicians, shows about books or computers or food—all community-based. The station could even step into the space abandoned by public radio in Boston and air a daily jazz show, like WCRX in Columbus, Ohio.

Best of all, a low-power FM station in Waltham would be owned and operated by a organization or group from the community.

I’m just using Waltham as an example here—it could be any city or town.

There are already 12 low-power FM stations in Massachusetts, each with a broadcast range of about 3.5 miles—just enough to create a local community of listeners. Seven of the existing LPFM stations in the state are owned by churches, Nichols College in Dudley owns one, and the other four are community stations.

The community stations are a pleasure to listen to—quirky, opinionated, eclectic. They all have web streams. Check them out: WBCR in Great Barrington, WVVY in Tisbury on Martha’s Vineyard, WXOJ in Northampton, and WMCB in Greenfield.

The Prometheus Radio Project, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit founded in 1998 to advocate for community radio stations, helps groups across the country looking to start community radio stations. When the FCC approved the new LPFM regulations, Pete Tridish of Prometheus waxed inspirational:

A town without a community radio station is like a town without a library. Many a small town dreamer—starting with a few friends and bake sale cash—has successfully launched a low power station, and built these tiny channels into vibrant town institutions that spotlight school board elections, breathe life into the local music scene, allow people to communicate in their native languages, and give youth an outlet to speak.

What would it take to be one of those small town dreamers who launches a low-power station—besides a heck of a lot of work and some devoted collaborators? Prometheus estimates “a fairly minimal” start-up investment in the necessary equipment would be about $10,000. The blog Engineering Radio has done a breakdown of the cost of starting a hyperlocal radio station and sets the cost of a full set-up somewhat higher. You can check out prices for equipment at The LPFM Store.

Some existing low-power stations are getting serious about doing community journalism. KSOW in Cottage Grove, Oregon (“Real Rural Radio”) just published a guide to radio journalism resources for its volunteers.

I’m dreaming, you say. No one listens to the radio anymore. (Actually, more than 90 percent of adults listen to the radio.)

At a time when so many community media outlets have become skeleton-staffed cells on a corporate spreadsheet in some distant finance department, we need to think creatively about community media.

The federal government, after a decade of stalling, is offering communities an opportunity to create new hyperlocal media. Who’s going to step forward and start creating community radio?