Key Terms

Algorithm

Analog

Animation

Audio

Automation

Batch Processing

Blog

Broadcasting

Communication

Content Sharing

Convergence

Designated Market Area (DMA)

Digital

Graphics

Hashtag

Hypertext

Linear

Mass Audience

Mass Media

Medium/Media

Microblogging

Multimedia

Narrowcasting

New Media

Nonlinear

Numerical Representation

Old Media

Paradigm Shift

Social Bookmarking

Social Media

Structural Modularity

Tag

Text

User-Generated Content

Video

Vlog

World Wide Web (WWW)

We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.

—Marshall McLuhan, communication theorist

The digital revolution is far more significant than the invention of writing or even of printing.

—Douglas Engelbart, inventor of the computer mouse

Chapter Highlights

This chapter examines:

- ■ Multimedia as an extension of traditional media industries and practices

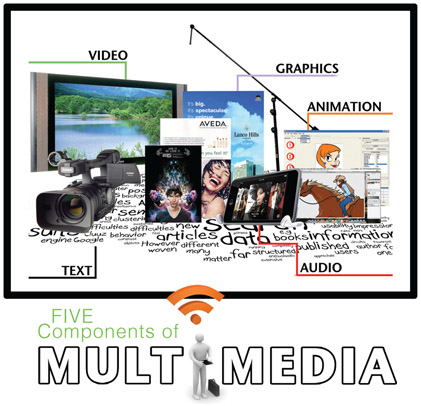

- ■ The five components of a multimedia experience

- ■ Three characteristics of old media

- ■ The new media paradigm shift

- ■ Five principles of new media in a digital age

What it is … is Multimedia!

In 1953, legendary comedian Andy Griffith recorded a monologue about a country preacher’s trip to a college town during a home football game. In this fictional tale, the preacher has traveled to the “big city” to conduct a tent meeting, but his plans are interrupted when he is unexpectedly caught up by a frenzied crowd as they make their way to a football stadium on game day. What follows is a hilarious first-person account about the culture and sport of football as witnessed through the eyes of someone who has never seen or played the game. With a limited vocabulary and frame of reference, he begins to describe the events around him using the only terms he understands. He refers to referees as convicts because of their striped uniforms. The football is called a pumpkin. And the playing surface is compared to a cow pasture that players enter through a “great big outhouse” on either end of the field. The skit, titled “What It Was, Was Football,” launched Griffith’s professional career, leading to a guest appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1954. The live radio recording remains a cult classic and is one of the biggest selling comedy recordings of all time.

At one time or another, all of us have been caught by surprise by a new experience or trend that sneaks up on us at lightning speed, challenging old ways and habits and leaving us scratching our heads in bewilderment. The country preacher’s first game of football reminds me of the challenge my mother must have experienced as she learned to send an email message or open a file attachment for the very first time. She was born in the 1930s and spent most of her life relying on pen, paper, and the U.S. postal system for sending and receiving correspondence. To her, this newfangled thing called email must have seemed like a strange and foreign idea. Perhaps you can think of a friend, grandparent, or child who has struggled finding the right words to describe social networking, online shopping, or surfing the Web. How does someone raised in the 1950s come to understand the World Wide Web? How does someone raised in the 1970s adapt to Facebook, Twitter, WordPress, and other social media channels?

For some of you, engaging in a formal study of multimedia will resemble the country preacher’s first time at a football game. The landscape will appear strange and foreign to you at first as you struggle for meaning in a sea of unfamiliar objects and ideas—even though you’ve probably spent plenty of time online. In time, a sense of comfort and familiarity will set in as you catch a glimpse of the big picture and begin to grasp some fundamental concepts and principles. To begin, let’s take a peek at something you are probably very familiar with that may serve as a common reference point for understanding multimedia.

The Legacy Media

The legacy media, or old media, as we will refer to them later in this chapter, are collectively the traditional forms of human exchange that have been around since the advent of mass communication. The word media literally means “ways of transmission” and is a broad term that applies to all the various technologies we rely on to

Great Ideas

Metaphor

It’s natural for us to draw upon past experiences when confronted with a new tool, system, or way of doing something. Familiar frames of reference, along with established patterns and workflows, can help us make sense of new technologies and methods of productivity. This may explain why metaphors are used so often to describe a new communication technology or activity (see Figure 1.1). For example, a computer’s main visual interface is called “the desktop” because it represents the virtual version of a real space where tools and documents reside for conducting everyday business. Likewise, folder icons are used to represent digital spaces on your computer’s hard drive for storing electronic documents in much the same way that cardboard folders are used for storing and sorting paper copies. In fact, we’re told to think of the hard drive as a file cabinet. We refer to online content as a “web page” because the book analogy makes sense to those of us familiar with print media and the structure of content arranged in a linear format. On Facebook we write messages on “the wall” and refer to the included members of our social network as “friends.” Metaphors are handy devices used to frame complex ideas in a way that nearly everyone can understand.

Figure 1.1

A 1983 promotional brochure from Apple Computer illustrates the power of a good metaphor. The Apple Lisa computer used these familiar picture icons to represent virtual versions of common everyday objects in a real office.

Source: Courtesy of Computer History Museum.

record information and transmit it to others. For example, videotape is a recording medium (singular) used for storing moving images and sound onto the physical surface of a magnetic strip. Television broadcasting and DVD (digital versatile disc) are transmission media (plural) used to deliver a video recording or live event to an audience. Likewise, printing is a medium whereby ideas are encoded as letterforms in ink onto the surface of a page, while books, newspapers, and magazines are the distribution channels or media through which intellectual content is delivered to a reader.

A medium can be thought of as a pathway or channel through which ideas, information, and meaning flow as they travel from one place or person to another. Every medium has a native form and structure through which it delivers content. A sound recording produces pressure waves that can be understood aurally through the organs of hearing. A book transmits ideas visually through text and illustrations. Video and film convey stories through moving images and sound. Traditional media products such as these have a physical structure that is rigid and fixed and cannot be easily modified or adapted by the user or content producer.

Figure 1.2

Source: Sarah Beth Costello.

Multimedia Defined

Multimedia can be thought of as a super-medium of sorts because it consolidates many of the previously discrete and non-combinable products of human communication (the legacy media forms) within a single convergent channel of expression and delivery. Stated simply, multimedia is any combination of these five components: text, graphics, video, audio, and animation in a distributable format that consumers can interact with on a digital device.

Text

The first component of multimedia is text, which is the focus of chapter 8. Text is the visual expression of letters, numbers, and symbols used to communicate ideas and information to others through a human language system. Of the five elements of multimedia, text is the most ubiquitous. It represents the vast amount of visual content in most multimedia page layouts. If you doubt this, just compare the use and extent of text on Facebook or your favorite website to the other multimedia components on the same page. While graphics may consume more physical space in a layout, it is text that most often provides the intellectual substance, detail, meaning, and context in a visual design or presentation. The purpose of text in a multimedia project is fourfold: 1) to provide instruction, 2) to provide a written narrative, 3) to provide hierarchical structure, and 4) to facilitate discovery.

Figure 1.3

Text can be used in countless ways to communicate ideas and information, provide direction and structure, and convey visual energy and emotion in a multimedia design.

Text Provides Instruction

We’ve come to rely intuitively on visual text prompts to navigate web pages or make choices about where to go and what to do via the visual interface on our smartphone, tablet, game console, or television. Next time you are in a public building, look for the EXIT sign above an outside door. You rarely notice signs like this until you need them, but they are kept there to guide you when the time arises. When the power goes out, they shine as illuminated beacons to guide you safely out of the building. Likewise, text prompts are the digital signage of multimedia interfaces. We know from experience that a button labeled HOME will take us immediately to the landing page of the website we are currently on or to the top level of a compound menu system. Similarly, we click on the BACK button to retrace our steps to pages we have recently explored. When we embed text with a reference (or hyperlink), it becomes hypertext, a clickable object that users can interact with to immediately jump to another page or screen. Hypertext is usually color coded and underlined on web pages because, as creatures of habit, we want a predictable visual reminder to help us distinguish normal text from hypertext.

Text Provides a Written Narrative

Text is also used to tell stories and to communicate information and ideas about people, places, animals, objects, events, and so forth. Much of the textual content on commercial websites is carefully written prose in the form of advertisements, articles, news stories, blogs posts, captions, and so on. In this capacity, the purpose of text is largely informational and descriptive, although it can just as easily be entertaining or inspirational. Chapter 4 reminds us that “content is the tangible essence of a work: the stories, ideas, and information that we exchange with others.” Text is the primary vehicle we use to deliver it.

Text Enables Hierarchy

In the context of a multimedia experience, the visual information on your screen is rarely equally weighted. Some textual elements are intended to have more significance than others. To this end, text is often used to provide structure and a hierarchical order to multimedia pages and screen layouts. For example, headings, like the one prior to this paragraph introducing the section, titled “Text Enables Hierarchy,” are included to help organize the contents of each chapter into meaningful parts, just as chapter titles are used to arrange the entire manuscript into logically ordered and related subsections. The style of the heading text above was intentionally made to look different from the paragraph text (or body copy) that surrounds it. Because the heading text features a bold typeface and a larger font size, it stands out—thereby capturing more attention and enabling the reader to clearly see it as a separate, yet related, element on the page.

Text Is Discoverable

Finally, text can also be used to categorize digital content so others can discover it and have access to it. One of the most common ways to categorize content is by tagging. A tag is a short descriptive keyword or term about the subject of a written post or uploaded file. Any text that is entered on a web page or attached as metadata to a file using a text-based editor can be recognized and found through a digital search. Tags do not even have to be visible to users in order to be found by a search engine. In the case of web pages, tags are often invisible to the user and are only recognized beneath the surface in the HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) head tag or page title. Web page authors use HTML tags to enhance search engine optimization (SEO), a practice that can increase the likelihood that a particular page or site will appear on the results page of a search engine query.

Hypermedia The term hypermedia refers to a host of digital technologies that allow for the presentation of multimedia content in a nonlinear form. Traditional media such as books and vinyl records have a native linear structure. Their contents are arranged in a fixed logical order of presentation from beginning to end and cannot be changed or modified by the reader or listener. Hypermedia, on the other hand, is not dependent on linear presentation alone, but allows the user to experience content in a nonlinear fashion. The path can vary depending on user-directed choices or spontaneous detours encountered along the way. Hypermedia is an extension of hypertext, a term coined in 1963 by technology pioneer and author Ted Nelson to describe text that is linked to other text, allowing the user to move between sections of text within the same page or between linked documents. In the case of hypermedia, the principle is applied to nontext elements. Hypertext and hypermedia are core elements of the World Wide Web, although the principles extend beyond the Web to any type of digital technology that allows users to randomly access content in a nonlinear way. The compact disc is a hypermedia technology because it allows users, in a nonlinear fashion, to skip tracks or change the loca tion of the playhead rapidly rather than having to fast-forward by linear means, as we used to, when advancing through a tape recording.

Figure 1.4 NASA.gov is an example of a multimedia-rich website that includes articles and other text-based resources, public television channels and programming, social media feeds, image archives, photo and video galleries, and much more.

Source: http://www.nasa.gov/

An online file that has been tagged can eventually be located and retrieved by a web search engine like Google, which uses powerful computer algorithms to organize and index the content of web pages and social media sites. You can also use text-based searching for locating tagged items within popular sites like Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Twitter, and YouTube. Those of you who use social media on a regular basis may be acquainted with the practice of attaching a hashtag to content you’ve posted or uploaded through one of these services. A hashtag combines the hash symbol (better known as the number sign on a keypad) with a short descriptive term or phrase comprised only of alphanumeric characters with no spaces (e.g., #multimedia, #text). The use of hashtags has grown into something of a cultural epidemic as people often overuse the practice or, worse, use it as a way of poking fun at themselves or others. In such cases, the hashtag becomes a part of the message rather than a way of relating the subject of the post to a specific topic or group of people.

Graphics

Figure 1.5

Graphics add dynamic visual support to multimedia narratives. They can be used to illustrate concepts and ideas as well as bring visual energy, emotion, and pizzazz to your design.

The second component of multimedia is graphics—the focus of chapters 9 and 10. While the importance of text cannot be overstated, a page or screen comprised entirely of text would come across to most of us as visually drab and one-dimensional. Graphics provide much of the visual sizzle and wow factor in a multimedia experience. The term graphics encompasses a broad variety of things, including digital photographs, illustrations, clipart, and any other type of still image that can be displayed on a digital screen or computer monitor. Having just talked about text, it’s worth mentioning here that words and phrases can also be presented in the form of a graphic. However, when text is rendered and saved as a graphic, it loses its identity and meaning as text and cannot be understood by search engines unless it is tagged with metadata. A graphics editing program such as Adobe Photoshop or Adobe Illustrator can be used to create and edit graphics. Photoshop is used for editing digital photos and bitmap graphics, where pixels serve as the building blocks of a digital image. Illustrator is used primarily for editing vector graphics, which are defined by paths formed by points, lines, curves, and shapes. Chapter 9 expands more fully on the difference between these two types of computer graphics formats.

Figure 1.6

Video is one of three time-based components of multimedia. Whereas text and graphics are static by nature, video is a moving image or motion picture. We typically watch video in a linear format, from beginning to middle to end over a fixed span of time.

Video

Video, the third component of multimedia, is an umbrella term for any type of motion picture system or format designed to capture and reproduce real-life movement across time. Video is covered at length in chapters 11 through 14. Today, the terms video and film are often used interchangeably when referring to television shows or movies. As a standalone medium, a television program or movie does not fully satisfy our definition of multimedia. However, when you package video into an interactive Blu-ray disc, it does. The Blu-ray disc contains a navigation menu that often includes a mix of text, graphics, animation, and sound. Likewise, when video is embedded into a web page or streamed online, the media skin or interface includes player controls for interacting with the content. Related content such as episode descriptions or program links may also be found nearby. Turning on subtitles adds the element of text to a video presentation.

Today, a cadre of devices can be used for shooting video, including traditional broadcast television cameras, video camcorders, HDSLRs (hybrid digital single lens reflex cameras), tablets, and smartphones. Nearly every laptop computer features a built-in camera, or webcam, for transmitting “live” selfies to connected parties during a Google Hangout, FaceTime, or Skype session. You can use this same camera to produce a video that you create and edit on your workstation before uploading it to your favorite social media site. The acronym NLE stands for nonlinear editing, the technology behind computer-based video editing. Today, the most popular professional NLE software programs are Adobe Premiere Pro, Apple Final Cut Pro, and Avid Media Composer.

Figure 1.7

Audio brings sound to our ears as either a standalone component or as a synchronized source tied to a visual narrative. It includes elements such as narration, dialog, sound bites, music, natural sound, and sound effects.

Audio

Audio is the fourth component of multimedia and refers to the aural content that’s created through the electronic capture and reproduction of sound. Audio is covered in detail in chapters 11 and 12. By definition, video assumes the inclusion of an audio component while the opposite isn’t true. Audio can serve as an independent element in the multimedia experience. Think about the last time you played a video game and how the music and sound effects contributed to the energy and excitement of the gaming experience. The element of sound is a potent time-based media element that can evoke memories and emotion or, at the very least, intensify them. Professional software tools such as Adobe Audition, Avid Pro Tools, and the popular free and open-source program Audacity are designed for audio recording, editing, mixing, and sweetening.

Figure 1.8

Mario is the fictional animated mascot for Nintendo’s popular video game franchise. Animation brings motion and lifelike qualities to computer-generated characters and objects over time. It is a common element of multimedia game design and an integral component of many film, video, website, and interface design projects.

Animation

Animation is the process of creating motion over time through the rapid projection of a sequence of hand-drawn or computer-generated images and falls into two broad categories: 2D animation and 3D animation. In 2D animation, motion is constrained to horizontal and vertical paths along the x-axis and y-axis. In 3D animation, the third dimension of depth (the z-axis) is achieved through algorithmic manipulation of form, lighting, texture, perspective, and other motion variables. The term animation can refer globally to a specific genre of storytelling or moviemaking, such as in the Disney classic Toy Story (1995), the first feature-length film produced entirely with computer animation. Animation can also be combined with live action or used in the production of short-form works such as television commercials, cartoons, and animated shorts. The term motion graphics is commonly used to describe the animation of still images and graphics such as company logos or text.

Within the specific context of multimedia, animation is integrated into many web-sites and user interfaces as well as in standalone gaming products and applications. Animated websites and interface components can be produced using Dynamic HTML, Flash, and a variety of scripting languages, programs, and plug-ins. For example, a rollover button is an interactive component on a web page that performs an animation whenever a user hovers over it or clicks on it with the mouse. Likewise, an animated GIF is a series of still image frames that play on screen to give simple motion to a single web object or graphic. Finally, a wide range of visual effects, such as dissolves, wipes, page turns, and so forth, can be used to add motion to multimedia elements and transitions—bringing visual eye candy and pizzazz to an otherwise static image, page, interface component, or screen.

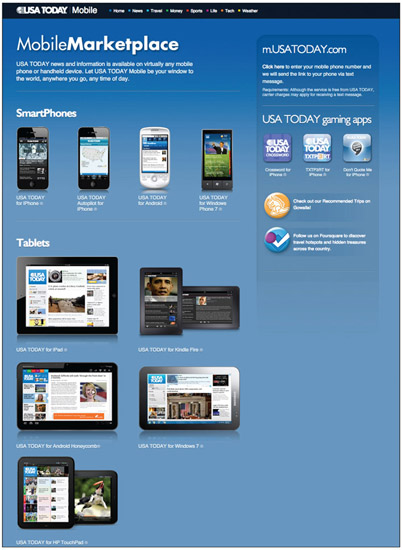

The World Wide Web

Invented by Tim Berners-Lee, the World Wide Web (WWW) became a reality in 1990 (see the chapter 7 Flashback entitled “A Brief History of the Internet and the World Wide Web”). For more than 20 years, the Web has been the dominant distribution platform for multimedia, and for many people today, it still is. However, in recent years, the Web has faced steady competition from newer technologies. While it remains a popular gateway to a plethora of multimedia content and experiences, more and more, users are producing and consuming multimedia through the growing cadre of “smart” devices and mobile media apps. Smartphones, smart TVs, tablet computers, gaming consoles, and similar devices are being touted as “multimedia enabled” by virtue of their ability to rapidly access nearly any form of media content from within the cloud or on the Web and through wireless Wi-Fior cellular connections (see Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9

In addition to delivering content through traditional print and online media channels, USA Today offers readers access to its branded content through a cadre of mobile news and gaming apps.

Source: http://www.usatoday.com

My Introduction to the Web

The year was 1993, and I was in a study lounge with fellow graduate students at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. We were seated around a small desk exploring a new software program that had just been installed on a Windows workstation. The program, called Mosaic (see Figure 1.10), was one of the first web browsers that could combine colored images with text on the same screen. The more I discovered about Mosaic’s web-surfing capabilities, the more I began comparing the experience to that of my parents’ generation, when people gazed upon broadcast television images for the very first time. Little did I know then that this nascent technology would change the world forever and affect me directly in my career as a video producer and media educator.

Figure 1.10

Mosaic 1.0 for Microsoft Windows was released in 1993 by the National Center for Supercomputing Applications. NCSA discontinued development and support for the browser in 1997.

Source: Courtesy of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) and the Board ofTrustees of the University of Illinois.

Mosaic faded into obscurity nearly as quickly as it came into existence, eclipsed by Netscape Navigator in 1994. Despite its short life span, Mosaic was known as the “killer application” of the 1990s and was the catalyst for making the Internet accessible to the general public. While the Internet had been in existence for two decades, the human interface was text based, cryptic, and visually uninteresting. Mosaic was one of the first web browsers to feature a graphical user interface (GUI), an object-oriented design that was visually intuitive and easy to use. Mosaic introduced the Web to the masses and took the Internet mainstream.

Today, much of the media content we consume is available in a variety of formats intended to serve multiple purposes and audiences. For example, a book typically starts out as a print-only product. However, if the market demand is high enough, it may also be published in a spoken-word format, as an audio book, and delivered via compact disc or MP3. With the right equipment, you can avoid paper altogether by downloading the e-book, a digital version of the text designed for reading on a computer screen or on a tablet such as Amazon’s Kindle Fire. The website for a bestseller may offer bonus material or value-added content to online users through a gamut of multimedia channels—featuring audio excerpts, video interviews, background stories, pictures, and more (see Figure 1.11). With such a vast sea of information and social networking potential, you can easily imagine many other possibilities. The opportunities for shaping content to meet the diverse needs and habits of different user groups are numerous and are evolving rapidly as the culture of multimedia continues to grow and permeate nearly every aspect of our personal and professional lives.

Three Generations of the Web

The evolution of the World Wide Web can be traced through three key stages of development, which are unofficially labeled Web 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0. The first generation of the Web, known as Web 1.0, covers the first decade of its existence from 1991 to 2001. This era was characterized by one-way communication and point-to-point exchanges of information. Web pages of this era usually mirrored the linear presentation and structure of a printed book. Static content, made up mostly of text and images, was consumed linearly in a traditional manner by reading from left to right and from top to bottom. User-generated content was unheard of, and there were few opportunities for interactivity, collaboration, or customization of the user experience. For most people, access to Web 1.0 was made possible through a low-bandwidth connection using a dial-up modem. While this was an adequate pipeline for the exchange of text and low-resolution graphics, it was not sufficient for handling the high-bandwidth transmissions of large files such as high-resolution images and streaming audio and video files.

Web 2.0 came into its own around 2001 following the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. This generation of the Web ushered in the era of rich media content, dynamic web pages, content management systems, content sharing and collaboration sites, tagging, wikis, blogging, social networks, and more. Web 2.0 was made possible in large part by the release of program authoring tools used for creating Rich Internet Applications (RIAs). An RIA is a web-based application such as Adobe Flash, Oracle, Java, Microsoft Silverlight, or HTML5. RIAs typically require the use of a supported browser, media player, or browser plug-in (such as Flash Player or QuickTime) to run programs and view content. RIAs are used for deploying “rich media” or “interactive multimedia” content to consumers. As the name implies, rich media is designed to enrich the user’s online experience by increasing opportunities for interactivity, customization, and personal control of a multimedia experience.

Figure 1.11

A companion website for the best-selling biography Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand offers readers value-added content about the author and her subject. Here, an interactive map offers details about key locations in the subject’s journey.

Source: http://laurahillenbrandbooks.com/.

Figure 1.12

World Wide Web is the name given to the vast system of interconnected servers used in the transmission of digital documents formatted using HTML via the Internet.

Timothy Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, coined the term Semantic Web to describe Web 3.0, which many see as the next significant iteration of the Web. The Semantic Web is defined as “a web of data that can be processed directly and indirectly by machines.”1 Web 3.0 will likely involve the creation of new standards and protocols for unifying the way that content is coded, organized, and analyzed by computers monitoring the Web. This may involve transforming the Web into a massive unified database akin to a virtual library. Such a vast library will require more sophisticated computers and search engines to categorize and make sense of its holdings. As computers become “smarter” and the engineering behind the Web grows more sophisticated, many believe we will see a significant increase in computer-generated content. Web 3.0 signals, in part, a larger role for computers as creators of intellectual content. Is a day coming when you will no longer be able to distinguish between content written by humans and machines? Has it already arrived?

Great Ideas

Social Media

Social media is a broad term used to describe a growing host of tools and services that enable computer-mediated interpersonal, group, and mass communication (see Figure 1.13). Increasingly, they also support sharing of multimedia content in diverse forms and contexts. Social media can be broken down into many different categories of services as related to their general purpose and focus. A few of the most popular channels are included here.

Figure 1.13

The rapid proliferation of social media sites such as those represented here has contributed to a growing phenomenon known as hyperconnectivity—whereby people stay perpetually connected to the Web and to one another through a host of digital devices and apps.

- ■ Social networking services such as Facebook, Snapchat, LinkedIn, and so on connect friends and people with common interests and backgrounds. They provide numerous opportunities for synchronous and asynchronous communication through features such as live messaging or chatting, email, updates, invitation and announcement posts, image and video sharing, and so forth.

- ■ Blogging engines such as Blogger and WordPress provide users with an online publishing tool for the regular posting of written stories or narrative commentaries. The term blog is a blended form of the phrase “web log.” Blogs often focus on a particular subject or offer news and insight from a specific point of view. They can also serve as a public space for personal reflections, such as you might find in a diary or travel journal. Celebrities, media practitioners, and organizations (journalists, critics, actors, singers, authors, public relations firms, etc.) use blogs for interacting with fans, consumers, or the general public. Video blogging, or vlogging (pronounced V-logging), is a hybrid form of blogging that uses video in place of a written narrative. Vlogs typically feature a headshot of the individual as he or she communicates directly to the audience through a webcam attached to a personal computer. Microblogging is a variation of the blogging concept that limits communication to short strings of text or video. Microblogging services such as Tumblr and Twitter integrate the text-messaging capabilities of mobile technologies such as the cell phone with the enhanced distribution channels of the Web and mobile apps.

- ■ A wiki is a tool that allows users to collaboratively create and edit documents and web pages online. Wikipedia, an online encyclopedic resource founded in 2001, is one of the most popular wikis. Entries in the Wikipedia database are posted and compiled interactively by a community of volunteers from around the world. Wikipedia is based on the MediaWiki platform. Like many of the wiki platforms, MediaWiki is free.

- ■ Content sharing sites enable the exchange of various forms of multimedia content. Commercial photo sharing services such as Flickr and Shutterfly allow users to order photographic prints, albums, cards, and other products from content uploaded by family members and friends. Instagram integrates mobile photo- and video-sharing with other social media services such Facebook, Twitter, Tumble, and Flickr. Video-sharing tools such as YouTube, Vimeo, and Vine allow users to upload and embed video in their social media sites. Other services enable users to share music, audio resources, music playlists, and channels (as with the integration of Pandora Radio’s online music service into Facebook and Twitter).

- ■ Social bookmarking services (such as Delicious) and news aggregators (such as Digg) allow users to rate and share the most popular sites and news articles on the Web.

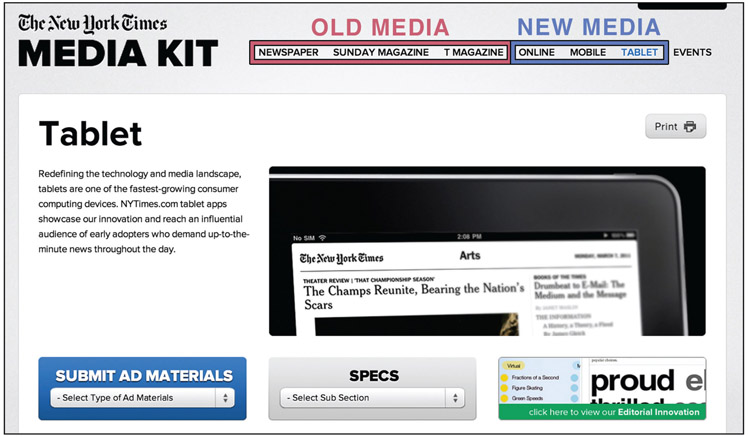

Old Media

The term old media has become synonymous with the seven original forms of mass communication: books, newspapers, magazines, film, sound recordings, radio, and television (see Figure 1.14), while the term new media is used to describe the relatively recent emergence of digital technologies that have changed the way content is produced, distributed, and consumed.

Figure 1.14

Old media. Seven industries are often grouped under the broad heading of mass media. The print media include books, newspapers, and magazines. Time-based media (also known as electronic media) include sound recordings, movies, radio, and television.

Old media can also refer to the discrete technologies, tools, practices, and work-flows that communication professionals have traditionally used to craft messages and stories. Journalists work with paper, ink, and words; photographers are the masters of communicating through the still image; graphic designers create visual illustrations and page layouts; and video producers, audio engineers, and filmmakers engage audiences through sound recordings and motion pictures.

The legacy media of old such as newspapers, television, and motion pictures are still with us. Being “old” does not mean they have disappeared or no longer provide a viable commodity for consumers. Rather it reminds us that the previous century’s models of mass media, which took many years to refine, are based on a different paradigm from those used by the new media platforms of the 21st century.

Paradigm Shift

Thomas Kuhn coined the term paradigm shift in 1962 as a way of describing monumental changes in the meanings of terms and concepts that would shake up the status quo, challenging the scientific community’s preconceived ideas and assumptions about natural phenomena. Kuhn was a proponent of aggressive puzzle-solving science, the sort of out-of-the-box thinking that would break new ground, pushing his colleagues away from routine practices of “normal” science that were rooted in established theories and methodologies. With Kuhn’s help, it may be better for us to think of old media as normal and new media as the inventive type, the kind that allows us to advance new ideas and methodologies of information sharing and social interaction. The old media were slow to change because of the tremendous investment in the physical infrastructure (television towers, printing presses, recording studios, etc.) and the high cost of producing and distributing content. The digital revolution and the birth of the World Wide Web represent two of the most important defining moments in the history of communication. The paradigm of old media was suddenly confronted with new ways of creating, delivering, and consuming content. A paradigm shift of epic proportions has occurred, and things will never be the same.

In the 1950s sociologist Charles Wright examined the mass media and found they share three defining characteristics:2

- 1. The mass media are the product of large organizations that operate with great expense.

- 2. The mass media are directed toward a relatively large, heterogeneous, and anonymous audience.

- 3. The mass media are publicly transmitted and timed to reach the most audience members simultaneously.

Large Organization

The first characteristic of old media is that they are the product of large organizations that operate with great expense. Hollywood movie studios, metro city newspapers, recording houses, television networks, broadcast television and radio stations, and book and magazine publishers are large entities employing many people with highly specialized skills and job functions. The concentration of media ownership has increased significantly over the years, leading to fewer and fewer companies owning more and more of the world’s mass media outlets.

In 2015, Forbes listed Comcast as the largest entertainment and media conglomerate in the United States with net revenues in excess of $68 billion.3 The top five also included The Walt Disney Company (#2), 21st Century Fox (#3), Time Warner (#4), and Time Warner Cable (#5). These are household names to many of us. Millions of people are touched daily by content delivered or produced by companies such as these or their subsidiaries. The start-up costs for a conventional media operation are high, which means that most people will never be able to own a television station or movie studio. Also, professional programming and content is difficult and expensive to create. A single episode of a primetime dramatic series can cost millions of dollars to produce.

The Consumer as Producer: The New Media Paradigm Shift

Consumers no longer have to rely solely on large organizations to provide them with news and entertainment. The shift to new media means that anyone can produce and deliver content to a public audience. User-generated content (UGC), or consumer-generated media (CGM), bypasses the formal gatekeeping functions and monopolistic control that characterize the old media factories of cultural production. This paradigm shift is sometimes referred to as the democratization of media because it empowers the individual with a multitude of outlets for personal expression. With a little bit of new media know-how, you can self-publish a book or compact disc, rule a country in Second Life, post a video on YouTube, send an iReport to CNN as a citizen journalist, maintain a blog or Twitter feed, create a website, manage a radio station, host a podcast, and so much more.

The opportunities for self-expression and commercial enterprise are virtually unlimited (see Figure 1.15). If the content you publish is compelling enough, you might even develop a significant following. Almost daily, we hear of people rising to celebrity status, sometimes almost overnight, by publishing an item of sensational interest on the Web. For example, think about how often you hear about a new viral video that is trending in the news or rapidly gaining views as word spreads through the social network grapevines. Word travels quickly through the emerging channels of social media as well as through the more established mainstream media outlets as they monitor and report on Internet trends and pop culture. As Andy Warhol so aptly predicted in 1968, “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” With new media and the Web, this has never been more likely.

Figure 1.15

Launched in 2006, CNN iReport gives users of CNN.com a public outlet for posting opinion pieces, news reports, photos, and video. The best submissions are marked with a red CNN iReport stamp, meaning they have been vetted and cleared for mainstream distribution on CNN.

Source: http://www.ireport.cnn.com.

Large Audience

Wright’s second characteristic of old media states that they are optimized to reach a large, anonymous, and heterogeneous audience. This characteristic identifies the receiver of a mass media message as a large group of people collectively known as “the audience.” For this reason, they are sometimes called the “mass audience.” The model of advertiser-supported media, which has been in use in the United States since the modern era of commercial printing and broadcasting, makes content available to consumers for free or at a partially subsidized cost. With this model, a media company generates revenue indirectly through the sale of commercial advertisements. A “mass” audience ensures a sufficient return on investment (ROI). Television programs will continue or be discontinued based on their ability to maintain a large audience. When audience numbers fall below a predetermined threshold or break-even point, a program is cut to minimize losses.

While media research and marketing analytics firms such as Nielsen and Alexa can provide aggregate data about the size and composition of a mass audience, the individual identities of people consuming mass media messages are largely unknown (see Table 1.1 through Table 1.3). An exception occurs with subscription services such as newspapers and magazines. Still, for every known person who subscribes, there are many anonymous users who acquire print products through point-of-purchase displays, magazine racks, street vendors, and the like.

Designated Market Area (DMA)

The United States is divided into 210 designated market areas (DMA) for television broadcasting. Each DMA represents a specific geographic area that is regionally served by local television stations transmitting over-the-air signals. The list of radio station DMAs is even larger because, due to FCC (Federal Communications Commission) power restrictions, their market size is typically much smaller than their television counterparts.

Table 1.1 The Top 25 Television Markets in the United States

Source: The Nielsen Company, January 1, 2015.

Note: For television, the DMAs are rank ordered from largest to smallest according to the number of television homes in each region.

The term broadcasting is a metaphor taken from earlier days when farmers sowed seeds manually by tossing them into the air with a sweeping movement of the hand. The farmer’s “broadcast” method of planting his fields ensured the seed would be evenly dispersed in the air before hitting the ground. Done correctly, this would produce a healthy crop of evenly spaced plants. Radio and television broadcasters use this principle to transmit programming to a mass audience. Based on the frequency and power allocation awarded to them by the FCC, they have a specific geographic region in which to operate. The broadcast signal is dispersed evenly over this area, falling randomly on home receivers that happen to be tuned in at any given moment. The opportunity to receive a broadcast signal is open to the public at large. While social and economic factors prevent some people

Table 1.2 U.S. Broadcast TV Ratings for Week of February 8, 2016

| Rank | Program | Network | Rating | Viewers (000) |

| 1 | NCIS | CBS | 10.4 | 16,941 |

| 2 | THE BIG BANG THEORY | CBS | 9.8 | 16,250 |

| 3 | CAMPAIGN 16 REP DEBATE | CBS | 8.1 | 13,443 |

| 4 | NCIS: NEW ORLEANS | CBS | 7.7 | 12,587 |

| 5 | SCORPION | CBS | 7.0 | 11,364 |

| 6 | BLUE BLOODS | CBS | 6.9 | 10,924 |

| 7 | 60 MINUTES | CBS | 6.5 | 10,417 |

| 8 | MADAM SECRETARY | CBS | 6.2 | 10,061 |

| 9 | NCIS: LOS ANGELES | CBS | 6.2 | 9,755 |

| 10 | LIFE IN PIECES | CBS | 5.7 | 9,348 |

Media companies and advertisers rely on audience research firms like Nielsen for statistical data about the consumption patterns of television viewers.

Source: The Nielsen Company. Viewing estimates here include live viewing and DVR playback on the same day, defined as 3 a.m.–3 a.m. Ratings are the percentage of TV homes in the United States tuned into television.

Table 1.3 Top 10 Websites in the United States

| Rank | Website |

| 1 | Google.com |

| 2 | Facebook.com |

| 3 | Amazon.com |

| 4 | YouTube.com |

| 5 | Yahoo.com |

| 6 | Wikipedia.com |

| 7 | eBay.com |

| 8 | Twitter.com |

| 9 | Reddit.com |

| 10 | Go.com |

Source: Alexa.com, October 27, 2015.

from owning a receiver, the wide distribution of the broadcast signal ensures delivery of the content to a diverse and heterogeneous audience. In order to appeal to a large and diverse audience, programming has to be broadly appealing to average groups of people or segments of the population. While programming can be targeted to specific groups such as men and woman, narrowing the focus too much can result in an audience size that’s too small to offset expenses or meet profit expectations.

Narrowcasting: The New Media Paradigm Shift

With new media, consumers have greater access to content that interests them the most. Tuned in to a traditional radio broadcast signal, a listener must conform to the linear presentation of a playlist as determined by the on-air announcer or music director of the station. While it’s possible to switch to a different station on the radio dial at any time, the presentation of musical selections is fixed and cannot be altered by the listener to fit his or her personal tastes and preferences. A new media paradigm shift has occurred with services such as Pandora, an Internet radio service. Pandora calls itself “a new kind of radio—stations that play only the music you like.” With Pandora, a user can enter the name of a favorite song or artist. The Pandora search engine will analyze the selection and generate a playlist based on similar styles of music. You can skip a song you do not like and a new song will begin. User feedback in the form of approvals, disapprovals, and skips provides Pandora with information it then uses to improve future selections and playlists. The term narrowcasting is used to describe the new media technique of delivering content of value to a niche audience with shared values and interests. Narrowcasting shifts power to consumers, enabling them to access the content they enjoy most, more quickly, and without having to be bound to linear and fixed methods of content distribution.

Figure 1.16

Like Pandora, the streaming music service Spotify allows users to create custom playlists and channels to fit their personal tastes and preferences. As with commercial radio, music streaming ventures like this are funded by advertising, keeping the basic service free to the consumer. Users can enjoy ad-free listening by paying a monthly or annual subscription.

Simultaneous Delivery

Wright’s third characteristic of mass media states that they are publicly transmitted and timed to reach the most audience members simultaneously. The mass media industries use expensive distribution systems to ensure a product is delivered to consumers in a timely manner. For example, a new motion picture is released to all theaters on the same day. The Wall Street Journal arrives in a subscriber’s mailbox on the publication date whether the reader resides in Atlanta or Milwaukee. Television networks go through great pains and lots of research to determine the best day of the week and time to air their programming. Once the schedule is set, consumers must align their schedules and expectations to fit the producer’s timetable.

Old media are also transient in nature. Mass mediated messages are available for a season, and once they’ve aired or become outdated, they are removed from circulation. Newspapers have a shelf life of only one day for a daily paper or seven days for a weekly edition.

Before the invention of home recording technologies such as VHS tape or the popular digital video recorder (DVR) TiVo, consumers had to conform to the broadcaster’s fixed program schedule. It was not unusual for families to alter their schedule to accommodate the viewing of a favorite television program. Today, consumers are no longer constrained to watching a program as it is being broadcast over the air or via cable at its regularly scheduled time slot. Instead, streaming services such as Amazon Instant Video, Apple iTunes, Hulu, and Netflix make television shows and movies available to consumers—for a fee, of course! In addition, cable and television networks routinely provide free access to recently aired episodes of their programs through their official websites.

New Media

The transition to new media began in the early 1980s with the proliferation of the personal computer (see Figure 1.17). The digital revolution, as it is often called, fundamentally changed many of the ways people work, produce, and interact with one another. It also opened up many new methods for the production and distribution of media content. In Being Digital, Nicolas Negroponte uses the phrase “from atoms to bits” to describe the revolutionary shift in the production of intellectual content from a material form consisting of atoms (film; printed matter such as books, magazines, and newspapers; phonograph records and cassette tapes; etc.) into an electronic format made up of bits (the invisible numeric output of computers and digital devices).4

Moving from atoms to bits is reflected in the transition from a print newspaper to an online version that readers consume on a computer screen. It means shifting from a physical book to a virtual one using a tablet computer and book-reading app. It means moving away from the distribution of content in a purely tangible format such as a record, tape, or compact disc to an electronic format that comes to us as a digital download. With digital content, a computer, tablet, or smartphone is needed to decode information from an encrypted format (or digital cipher) into human symbols and sounds that we recognize and comprehend. Material content (made of atoms) must be transported by hand (person to person, postal service, FedEx, etc.). Digital information is more easily transferable from person to person and across geographic space. In fact, the distribution possibilities are nearly endless. Bits can travel across telephone lines, via fiber optic cable, or through the airwaves using wireless transmission systems.

Figure 1.17

New media extends the reach and capabilities of all forms of media content to consumers through a host of new methods and delivery channels.

For decades, media producers had little choice but to use physical media (made of atoms) for recording and archiving content. Early photographic images were recorded on metal and glass plates and later on celluloid film. Animations used to be entirely hand drawn by the artist frame by frame on a transparent sheet of thermoplastic called a cel (short for the celluloid material it was made from). Sound and video were captured and edited on magnetic tape. Books and printed materials were published using mechanical typesetting equipment and paper. Being digital means moving away from traditional processes that depended so heavily on proprietary platforms and methods of creative expression.

Today, a growing number of photographers routinely shoot and edit their own video stories; graphic designers are busy retraining as web designers in order to retain a job or advance in a career; video and film have become nearly synonymous terms, having been unified (at least in part) through significant advancements in digital imaging and editing technologies; and journalists are fighting for survival as the traditional products of the information age, such as the newspaper, are growing less viable in a digital marketplace driven by instant access, free content, and mobile delivery. More than ever before, media professionals are crossing historic lines that have previously defined who they are and how they produce and deliver content to consumers. What lies on the other side can be exciting or scary, depending on your point of view and ability to adapt rapidly to change.

In his book The Language of New Media, author Lev Manovich uses the phrase “the computerization of media” to highlight what he sees as the primary distinctions between old and new media. According to Manovich, “just as the printing press in the fourteenth century and photography in the nineteenth century had a revo lutionary impact on the development of modern society and culture, today we are in the middle of a new media revolution—the shift of all culture to computer-mediated forms of production, distribution, and communication.”5 In the new media era, the computer assumes a dominant role as the universal instrument of inspiration, creation, distribution, and consumption, radically transforming old methods and workflows that have defined media production and cultural transmission for centuries (see Figure 1.19).

Figure 1.18

Old media haven’t died, but, rather, they’ve evolved and adapted as the technology infrastructures and platforms became digital and converged—leading to many changes in how media content is now delivered and consumed.

Figure 1.19

In addition to its traditional print products, the New York Times offers advertisers access to new media channels (online, mobile, and tablet).

Source: http://www.nytmediakit.com.

Five Principles of New Media

Manovich goes on to list five principles of new media that he says reflect the “general tendencies of a culture undergoing computerization.” He named these principles 1) numerical representation, 2) structural modularity, 3) automation, 4) variability, and 5) cultural transcoding. While not entirely exclusive to new media, this list identifies some of the most significant differences between the media of today and those of previous generations.

Numerical Representation

The first principle of new media is called “numerical representation” and states that new media objects can be defined numerically as a formal equation or mathematical function. The computer reduces every act of human communication to a binary expression made up of zeros and ones (bits).

Old media relied on analog methods of reproduction and distribution. An analog audio or video recording is represented by a continuous signal, whose physical qualities vary across time along a linear path. For example, when listening to a phonograph recording, the stylus is placed in the groove of a vinyl record. As the record spins, the stylus (usually a diamond or other hard stone) advances along a spiral path while sensing minute variations in the structure of the groove. The stylus stays in direct contact with the record at all times, resulting in the reproduction of a continuous uninterrupted sound signal. The vibrations picked up by the stylus correspond directly to the fluctuating properties of a live sound performance across time. The term analog is used to describe this type of process because the man-made recording is directly comparable to the physical properties of the original sound source.

The digital sound recording process is different. A digital audio recorder converts the properties of sound to a numerical value at discrete intervals of time. Each point of measurement is called a sample. In professional audio recording, sound is sampled at 48 kHz (or 48,000 times per second). This means that every 1/48,000th of a second, the computer measures the sound source’s physical properties and records them as a data file. In a digital recording, the value of each sample is retained in numerical form, allowing it to be individually addressed and affected mathematically. While it would be difficult and impractical to try to edit 48,000 individual samples of a one-second audio clip, the fact that a digital signal is numerical opens up opportunities that were impossible to achieve before computerization. New media, because they are digital, are naturally subject to algorithmic control and manipulation.

Tech Talk

Algorithm An algorithm is a mathematical sequence or set of instructions for solving a problem. The software tools used in multimedia design and editing employ mathematical algorithms to systematically rewrite the numeri cal data structure of a computer file. This results in a wonderful partnership between people and machines. The designer can focus on the creative tasks of authoring and content creation while the computer performs the math, crunching numbers at an amazing speed behind the scenes while the designer works.

Like a digital audio recorder, a digital camera uses sampling to create a digital image. Before computerization, photography involved the production of a “continuous” tone image on a sheet of film emulsion. Held up to a light and magnified, the negative imprint of the image was uninterrupted, a perfect analog of the intensity of light captured by the photographer through the lens of the camera. With a digital still camera, the image plane is broken down into a grid made up of millions of individual light-sensing picture elements called pixels. The computer saves the color information of each pixel, or sample, as a numeric value and stores it in the image’s data file. Math is an integral part of the process, and the computer uses algorithms to both compress and modify the pixel values. For example, applying the blur tool in Adobe Photoshop to a digital image causes the pixels in the path of the tool’s cursor to lose focus and soften. As you move the tool across the image, the appearance of each pixel it interacts with is visibly altered. In the background, what’s really happening is that the numerical value of each affected pixel is being changed to reflect the altered state of its new appearance. As you change the properties of a tool (e.g., make the brush tip bigger or lighten the stroke intensity, etc.), the underlying algorithm is adjusted to yield the desired effect (see Figure 1.20).

Convergence

Convergence is a term used to describe the merging of previously discrete technologies into a unified whole. A digital smartphone is the perfect example of convergence at work in a new media device. The primary function of a smart-phone is telecommunication, enabling the user to have a conversation with a distant party on the other end of the line. This function preserves the original purpose of the telephone as an instrument of person-to-person voice communication. The smartphone, however, is much more than a telephone appliance—it’s a mobile wireless device capable of 1) surfing the Web; 2) capturing still images, video, and sound; 3) texting using the industry-wide SMS protocol (or Short Message Service); 4) sending and receiving images, video, sound, newsfeeds, ringtones, and so on using the industry-wide MMS protocol (Multimedia Messaging Service); 5) downloading, uploading, and storing digital content; 6) running software apps; 7) location and navigation services (using built-in GPS [Global Positioning System] technology); and 8) playing multimedia content (music, video, etc.). A smartphone is essentially a computer. It has a microprocessor, operating system, RAM (random access memory), and storage media. Because of this, the smartphone can become anything a computer software application will allow it to become.

Convergence is a product of the digital revolution, made possible by the commonalities of a shared binary language system. Before the computerization of communication media, each system and tool functioned according to the principles of a proprietary design and system architecture. The tools of old media— cameras, televisions, cassette tape recorders, telephones, and so forth—were discrete inventions designed to perform a single primary function. Combining such a divergent mishmash of technology together was like mixing oil and water.

In the absence of a common structural platform, convergence was not possible (see Figure 1.21).

Figure 1.20

Using Adobe Photoshop, various visual effects were applied to the original image of the hurdler to achieve the four altered versions. Effects such as these are produced by the software mathematically through algorithmic manipulation.

Structural Modularity

As we continue our discussion of Manovich’s principles of new media, you will notice they are somewhat interdependent and often build upon previous attributes in the list. Thus, we can say that the second principle of new media, called structural modularity, is made possible because of new media’s property of numerical representation. Modularity means that a new media object retains its individuality when combined with other objects in a large-scale project. This is only possible because the computer sees each structural element in a design as a distinct mathematical object or expression.

Figure 1.21

In the not-too-distant past, a phone was just a phone. It was used for the sole purpose of establishing voice communication between two people. Today, the smartphone represents the convergence of many previously discrete communication technologies. It is a “multimedia enabled” device that functions more like a computer than the telephone some of us remember from earlier days.

The principle of modularity isn’t limited to text alone. To illustrate, let’s take a look at a common multimedia program many of you may be familiar with. A Microsoft PowerPoint presentation is a good example of structural modularity at work in the new media age. A PowerPoint slideshow is made up of a collection of slides positioned and arranged in a logical order of presentation. The designer can apply a unique transition or timing function to each slide individually, or he or she may choose to assign a single effect globally to all the slides in the presentation. Each slide is populated with its own unique content and design elements (text, graphics, video, sound, background image, etc.), each of which can be individually altered without affecting the others. The principle of structural modularity allows you to build a project from the ground up, one piece at a time, without losing independent control of each of the constituent parts of the whole.

In PowerPoint, as in many other programs, a designer can interact with a project’s content on multiple levels. On the macro level, you can edit global properties such as the slide template and background colors. It’s also possible to interact with multiple objects simultaneously by grouping them and manipulating them as one. On a micro level, you can make changes to a single element on a particular slide. For example, an image on the first slide can be cropped or resized without affecting content on the second slide. Likewise, a style can be applied to a single letter, word, sentence, or paragraph, simply by selecting the portion of text you wish to transform (see Figure 1.22).

Figure 1.22

This composite image, created in Adobe Photoshop, is constructed of four separate elements: 1) sky, 2) sun, 3) person, and 4) house. Each element resides on its own editable layer, allowing the designer to alter each constituent part of a design independently of the others.

Source: Adobe product screenshot reprinted with permission from Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Structural modularity is most valuable during the editing phase of a project, prior to the point when you export it for distribution or deployment. Most multimedia software tools, such as those used for photo, video, and audio editing, are designed to give you total control of the project assets and elements during the editing process. Once editing is complete, however, you’ll usually export the project for distribution in a compressed and uneditable file format. As an example, the native file format for Adobe Photoshop is .psd (Photoshop Document Format). As long as you are working in the original PSD version of a graphic or image file, you will be able to edit all the constituent parts of the graphic (layer objects, text, styles, etc.). When you are ready to put the image online, however, you’ll need to convert it to a JPG, GIF, or PNG file (we’ll learn more about these later). These distribution formats, while web friendly, are uneditable. They are only intended for viewing with a browser such as Chrome or Safari. Structural modularity is preserved only in the original native file format of the application that created it.

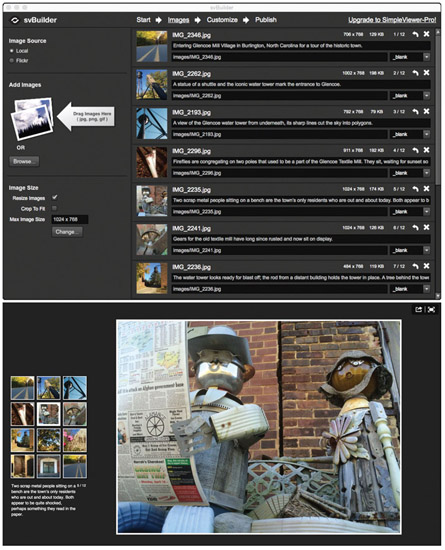

Automation

According to Manovich, digitization and structural modularity are the antecedents upon which the third principle of new media, automation, is predicated. With automation, the computer can be programmed to serve as an agent of content production. Low-level creative tasks can be carried out through automated machine processes or preprogrammed batch sequences. This feature can save time and often requires little expertise on the part of the user.

The power of automation can be demonstrated with SimpleViewer, a free cross-platform software program that allows users with no advanced coding or programming skills to create a professional image gallery for the Web in a matter of minutes. The first step to creating an image gallery with SimpleViewer is to drag the images you want included in the gallery to a designated drop zone. A user-friendly interface then walks you through the few easy steps of sorting the images, adding captions, and customizing the slideshow’s visual design and interface. The final step is to click on the Publish button to create the gallery. The publishing step initiates a script that automatically generates all the programming scripts, code, and web files needed to make the gallery function online (see Figure 1.23).

Figure 1.23

The photo story shown here (bottom) was created using SimpleViewer (top), a free application for creating a customizable image gallery for the Web.

Source: Courtesy of Kaz Colquitt.

The software and web-based tools of multimedia creation grow more sophisticated each year. Prebuilt templates and user interface components, widgets, scripts, and style sheets are just a few of the things users can utilize to fully or partially automate complex operations. While software tools and web applications are increasingly more intuitive and intelligent with each new release, computerized automation has yet to replace the human element. Producers should strive to embrace the potential efficiencies of workflow automation without sacrificing the autonomy and aesthetic sensibilities of the content creator. In short, some tasks ought never to be delegated to the computer.

Variability

Manovich’s fourth principle of new media is variability. It states that new media objects are not bound to a single fixed form but can exist, and often do, in a “potentially infinite” number of versions. As I’ve already noted, it’s common practice to create and edit projects in one format while distributing them in another. For this reason, new documents and project files are usually saved first in the native file format of the application that created them. For example, a Microsoft Word document originates as a .doc or .docx file. A Photoshop project is saved natively using the .psd file format. Professional sound recordings often start out as uncompressed WAV or AIFF audio files. And a digital video project may include source material that was acquired in a QuickTime or MPEG-4 compression format.

Before publishing a Word document to the Web, however, it’s best to convert it to a more widely accessible format such as PDF (Postscript Document Format). PDF is a universal file format that nearly everyone with a computer and Internet access will be able to download and read. After conversion, the same document will now

Tech Talk

Batch Processing Batch processing is the execution of a series of sequential actions performed by a digital device or software application. For example, one repetitive task I find myself doing often is selecting, sorting, and renaming digital images after a photo shoot. I can perform this type of activity manually, or I can turn to a computer and software program to assist me. For a job like this, I usually turn to Adobe Bridge. Using the virtual light box in Bridge, I begin by selecting the keepers, the images I like best and would like to see included in my project. Next, I rearrange them by dragging and dropping them into a desired sequence order. Finally, I choose the Batch Rename option from the Tools menu to automatically apply a renaming algorithm to my sorted images. The Batch Rename properties window provides me with several options for specifying a file name prefix and sequence number.

As Figure 1.24 shows, I enter the word image in the text field for the prefix and select a three-digit sequence number for the second part of the naming protocol. The result will be as follows: image001.jpg, image002.jpg, image003. jpg, and so on. After entering all the required information, I click on the Rename button to perform the automated process—and just like that it’s done. Without automation, even a simple procedure like this can end up taking a lot of time to manually perform, particularly when working with a large collection of images. Automation saves me time and effort I would rather not waste completing low-level menial tasks such as renaming files. It also ensures the process is performed flawlessly, without the human mistakes that are more likely to occur during manual editing. A savvy multimedia producer stays on the lookout for tools and automated processes that can speed up or enhance workflow productivity and performance.

Figure 1.24

The Batch Rename tool in Adobe Bridge is used to automatically rename five selected image files (top) and copy them to a new folder (bottom).

Source: Adobe product screenshot reprinted with permission from Adobe Systems Incorporated.

exist in two different formats. I will retain a copy of the MS Word version (.docx) in case I ever need to make changes to the original document or export it in a another format. The PDF version will be used only as a distribution format for making the document available to others.

Likewise, I often use Adobe Photoshop to create graphics for the Web. However, before publishing a graphic to the Web, it must be saved in a browser-friendly format such as JPEG, GIF, or PNG. To minimize file size and conserve bandwidth during transmission, online music files and podcasts are usually distributed in a compressed format such as MP3 or AAC. As a final example, in order to burn an HD video project to Blu-ray disc, the video must be encoded in the MPEG-4 file format while the audio is encoded to AC3.

The principle of variability means you can export, convert, or transcode digital files for a variety of purposes—to accommodate multiple distribution channels or to conform to a designated industry standard as appropriate. Because digital content is numerical, the data structure can be altered mathematically, allowing files to be re-encoded any time the need arises (see Figure 1.25).

Figure 1.25

A graphics editor such as Adobe Photoshop offers users many different format options when it comes to saving and exporting bitmap images. Photoshop’s native file format is PSD. Some other popular formats you are likely to run into are JPEG, TIF, PDF, and PNG.

Source: Adobe product screenshot reprinted with permission from Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Cultural Transcoding

Manovich’s fifth principle of new media delves deeply into the theoretical implications of using computers to represent the various products of human culture. He uses the term cultural transcoding to describe the bidirectional influence of computers and human culture acting reciprocally upon one another. With old media, the methods of production and distribution were based largely on organic processes that conformed to the natural properties of a specific medium or method of reproduction. Sound and light were captured and stored in a way that attempted to preserve the native structure and form of physical properties in a natural way. Manovich believes new media is partitioned into two competing parts, which he calls the “cultural layer” and the “computer layer,” and that each of these layers is constantly at work influencing the other. The merging of the two layers is producing a new “computer culture”—“a blend of human and computer meanings, of traditional ways in which human culture modeled the world and the computer’s own means of representing it.” In the words of Marshall McLuhan, “We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”6

In the mid-1990s, Nicholas Negroponte, then director of MIT’s Media Lab, argued that the world’s economy was moving rapidly from the production of material objects comprised of atoms to immaterial ones made of bits. He knew that any object of human creativity that could be digitized could also, then, be delivered to consumers via the world’s growing networks of computer and telecommunication systems. Digital platforms would become the dominant means for designing, producing, and distributing ideas in the next information age. Fewer than 20 years after his forecast, history has proven this to be true. Amazon now sells more e-books per year than physical books; YouTube is the largest distributer of streaming video content in the world, with an estimated 300 hours of video content uploaded every minute;7 and, if Facebook were a country, it would be the largest nation on earth, with a monthly active user population of 1.39 billion people.8 Physical letters and cards? Who needs such primitive and time-consuming methods of communication when you can post an electronic message, photo, or video to the wall? The move from physical to digital production and consumption has rapidly reshaped how people interact with one another and how users consume the media products professionals create. With new media, the consumer is potentially just as influential as the producer. In fact, we can no longer speak in such archaic ways about consumers and producers. In the multimedia age, everyone can be both and often is.

In this first chapter, we have defined multimedia as any communication event that combines text, graphics, video, audio, and animation though a digital channel or device. Understanding multimedia requires an appreciation for the traditional mass media industries and systems that have influenced human communication for more than 100 years. For the time being, old media such as broadcast television, books, newspapers, radio, and so forth remain relevant and are an important part of the media mix we continue to enjoy; however, the legacy industries of mass media have been forced to adapt and evolve within a radically changing paradigm and economic model. Likewise, consumers have also been forced to accept change—for one, transitioning from basic phones to smartphones! The digital revolution brings with it a whole new set of technologies, concepts, and workflows that we are being challenged to embrace and understand. As with many things, understanding multimedia requires us to explore the present and to engage the future through the lens of past experience and practice.

Notes

1 Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J., & Lassila, O. (2001, May 17). The Semantic Web: A new form of Web content that is meaningful to computers will unleash a revolution of new possibilities. Scientific American Magazine 284(5), 34–43.

2 Wright, C. R. (1959). Mass communication: A sociological perspective. New York: Random House.

4 Negroponte, N. (1996). Being digital. New York: Vintage Books.

5 Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

6 McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. New York: McGraw-Hill.