- 15 -

THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS

OF THE SUBPRIME CRISIS:

THE RESULTS OF CONTAGION

OR COMMON FUNDAMENTALS?

In the preceding two chapters we emphasized the similarities between the latest financial crisis (the Second Great Contraction) and previous crises, especially when viewed from the perspective of the United States at the epicenter. Of course, the crisis of the late 2000s is different in important ways from other post-World War II crises, particularly in the ferocity with which the recession spread globally, starting in the fourth quarter of 2008. The “sudden stop” in global financing rapidly extended to small-and medium-sized businesses around the world, with larger businesses able to obtain financing only at much dearer terms than before. The governments of emerging markets are similarly experiencing stress, although as of mid-2009 sovereign credit spreads had substantially narrowed in the wake of massive support by rich countries for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which we alluded to in the previous chapter.1

How does a crisis morph from a local or regional crisis into a global one? In this chapter we emphasize the fundamental distinction between international transmission that occurs due to common shocks (e.g., the collapse of the tech boom in 2001 or the collapse of housing prices in the crisis of the late 2000s) and transmission that occurs due to mechanisms that are really the result of cross-border contagion emanating from the epicenter of the crisis.

In what follows we provide a sprinkling of historical examples of financial crises that swiftly spread across national borders, and we offer a rationale for understanding which factors make it more likely that a primarily domestic crisis fuels rapid cross-border contagion. We use these episodes as reference points to discuss the bunching of banking crises across countries that is so striking in the late-2000s crisis, where both common shocks and cross-country linkages are evident. Later, in chapter 16, we will develop a crisis severity index that allows one to define benchmarks for both regional and global financial crises.

Concepts of Contagion

In defining contagion, we distinguish between two types, the “slow-burn” spillover and the kind of fast burn marked by rapid crossborder transmission that Kaminsky, Reinhart, and Végh label “fast and furious.” Specifically, they explain:

We refer to contagion as an episode in which there are significant immediate effects in a number of countries following an event—that is, when the consequences are fast and furious and evolve over a matter of hours or days. This “fast and furious” reaction is a contrast to cases in which the initial international reaction to the news is muted. The latter cases do not preclude the emergence of gradual and protracted effects that may cumulatively have major economic consequences. We refer to these gradual cases as spillovers. Common external shocks, such as changes in international interest rates or oil prices, are also not automatically included in our working definition of contagion.2

We add to this classification that common shocks need not all be external. This caveat is particularly important with regard to the recent episode. Countries may share common “domestic” macroeconomic fundamentals, such as housing bubbles, capital inflow bonanzas, increasing private and (or) public leveraging, and so on.

Selected Earlier Episodes

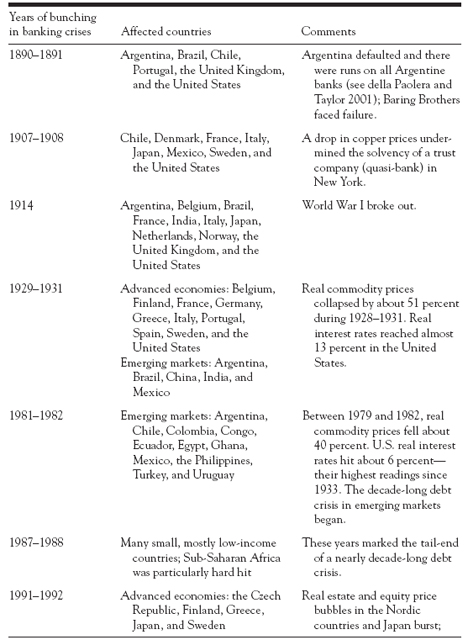

Bordo and Murshid, and Neal and Weidenmier, have pointed out that cross-country correlations in banking crises were also common during 1880-1913, a period of relatively high international capital mobility under the gold standard.3 In table 15.1 we look at a broader time span including the twentieth century; the table lists the years during which banking crises have been bunched; greater detail on the dates for individual countries is provided in appendix A.3.4 The famous Barings crisis of 1890 (which involved Argentina and the United Kingdom before spreading elsewhere) appears to have been the first episode of international bunching of banking crises; this was followed by the panic of 1907, which began in the United States and quickly spread to other advanced economies (particularly Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, and Sweden). These episodes are reasonable benchmarks for modern-day financial contagion.5

Of course, other pre-World War II episodes of banking crisis contagion pale when compared with the Great Depression, which also saw a massive number of nearly simultaneous defaults of both external and domestic sovereign debts.

Common Fundamentals and

the Second Great Contraction

The conjuncture of elements related to the recent crisis is illustrative of the two channels of contagion: cross-linkages and common shocks. Without doubt, the U.S. financial crisis of 2007 spilled over into other markets through direct linkages. For example, German and Japanese financial institutions (and others ranging as far as Kazakhstan) sought more attractive returns in the U.S. subprime market, perhaps owing to the fact that profit opportunities in domestic real estate were limited at best and dismal at worst. Indeed, after the fact, it became evident that many financial institutions outside the United States had nontrivial exposure to the U.S. subprime market.6 This is a classic channel of transmission or contagion, through which a crisis in one country spreads across international borders. In the present context, however, contagion or spillovers are only part of the story.

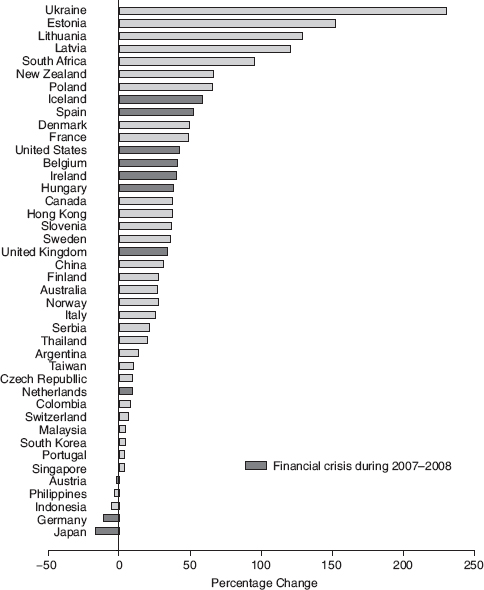

That many other countries experienced economic difficulties at the same time as the United States also owed significantly to the fact that many of the features that characterized the run-up to the subprime crisis in the United States were present in other advanced economies as well. Two common elements stand out. First, many countries in Europe and elsewhere (Iceland and New Zealand, for example) had their own home-grown real estate bubbles (figure 15.1). Second, the United States was not alone in running large current account deficits and experiencing a sustained “capital flow bonanza,” as shown in chapter 10. Bulgaria, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, New Zealand, Spain, and the United Kingdom, among others, were importing capital from abroad, which helped fuel a credit and asset price boom.7 These trends, in and of themselves, made these countries vulnerable to the usual nasty consequences of asset market crashes and capital flow reversals—or “sudden stops” á la Dornbusch/Calvo—irrespective of what may have been happening in the United States.

TABLE 15.1

Global banking crises, 1890-2008: Contagion or common fundamentals?

Sources: Based on chapters 1-10 of this book.

Direct spillovers via exposure to the U.S. subprime markets and common fundamentals of the kind discussed abroad have additionally been complemented with other “standard” transmission channels common in such episodes, specifically the prevalence of common lenders. For example, an Austrian bank exposed to Hungary (as the latter encounters severe economic turbulence) will curtail lending not only to Hungary but to other countries (predominantly in Eastern Europe) to which it was already making loans. This will transmit the “shock” from Hungary (via the common lender) to other countries. A similar role was played by a common Japanese bank lender in the international transmission of the Asian crisis of 1997-1998 and by U.S. banks during the Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s.

Figure 15.1. Percentage change in real housing prices, 2002-2006.

Sources: Bank for International Settlements and the sources listed in appendix A.1.

Notes: The China data cover 2003-2006.

Are More Spillovers Under Way?

As noted earlier, spillovers do not typically occur at the same rapid pace associated with adverse surprises and sudden stops in the financial market. Therefore, they tend not to spark immediate adverse balance sheet effects. Their more gradual evolution does not make their cumulative effects less serious, however.

The comparatively open, historically fast-growing economies of Asia, after initially surviving relatively well, were eventually very hard hit by the recessions of the late 2000s in the advanced economies. Not only are Asian economies more export driven than those of other regions, but also their exports have a large manufactured goods component, which makes the world demand for their products highly income elastic relative to demand for primary commodities.

Although not quite as export oriented as Asia, the economies of Eastern Europe have been severely affected by recessions in their richer trading partners in the West. A similar observation can be made of Mexico and Central America, countries that are both highly integrated with and also significantly dependent on workers’ remittances from the United States. The more commodity-based economies of Africa and Latin America (as well as the oil-producing nations) felt the effects of the global weakness in demand through its effect on the commodity markets, where prices fell sharply starting in the fall of 2008.

A critical element determining the extent of the damage to emerging markets through these spillover effects is the speed at which the countries of the “north” recover. As cushions in foreign exchange reserves (built in the bonanza years before 2007) erode and fiscal finances deteriorate, financial strains on debt servicing (public and private) will mount. As we have noted, severe financial crises are protracted affairs. Given the tendency for sovereign defaults to increase in the wake of both global financial crises and sharp declines in global commodity prices, the fallout from the Second Great Contraction may well be an elevated number of defaults, reschedulings, and/or massive IMF bailouts.