Portraits from the Mind

I noted toward the end of the Orientations that opened this book that I would not be able, for reasons of space, to give more than minimal consideration to the actual experience of Alzheimer’s as it affects individuals and their families. I am acutely aware that what is missing almost entirely from this treatise is the ultimate, undeniable reason for the existence of the Alzheimer enterprise—the anguish and suffering that this condition brings to millions of individuals and their families. In closing I want to draw readers’ attention to a remarkable set of paintings by the artist William Utermohlen that he produced after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. These paintings (A1–A4) draw one into the terrifying, miserable experience of losing one’s mind with heartrending clarity. My attention was first drawn to the work of Utermohlen when I came across an article about him in The Lancet, published in 2001. And then at the large international Alzheimer meeting held in Chicago in 2008, I went to an exhibition of Utermohlen’s work sponsored by Myriad Genetics, shown at the Chicago Cultural Center. This exhibition was a retrospective in four parts of the artist’s work before and after his diagnosis with Alzheimer’s disease and included his early portraits (1955–77); the Dante Cycle (1964–66) and the Mummers Parade Cycle (1969–70); Conversation Pieces (1990–91), and, finally, The Last Portraits (1995–2000).

William Utermohlen lived from 1933 to 2007 and was diagnosed with AD in 1995. He was born in South Philadelphia, the only son of a first-generation German immigrant, and attended art school in Pennsylvania. He later moved to England, where he continued his art training and was particularly influenced by the pop art of R. B. Kitaj. He married the art historian Patricia Redmond in 1965 and settled in London, where he lived out his life. After his diagnosis he was taken care of at home by his wife, friends, and caregivers, but his deterioration made it necessary in 2004 to place him in a nursing home, where he eventually died.

The authors of The Lancet article inform us that Utermohlen’s family had no history of neurological or psychiatric illness and that his medical history was unremarkable except for a car accident at the age of 55 in which he was left unconscious for about 30 minutes. After assessment when he was first referred to a neurologist, he was given at age 61 a diagnosis of “probable Alzheimer’s disease.” His wife traced the beginning of her husband’s problems back to a point several years earlier in his life. The age of onset of the disease was, then, very early indeed, but, with no family history of neurological disease, it could not have been dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. By age 65 Utermohlen was showing a “global deterioration in his cognitive state.”1 At this time he agreed with his doctors that he would attempt to continue painting as long as possible in part to assist in helping others to understand what was happening to him neurologically. Patricia Utermohlen commented, “As each small self-portrait was completed, William showed it to his nurse, Ron Isaacs. Ron visited the studio, photographing every new work. Ron’s conviction that William’s efforts were helping to increase the understanding of the deeply psychological and traumatic aspects of the disease undoubtedly encouraged William to continue.”2

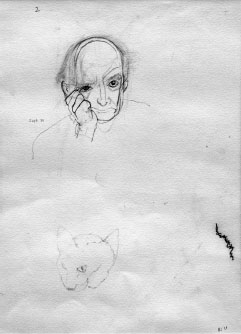

All his life Utermohlen had experienced a strong desire to draw people, as is strikingly illustrated by his colorful pictures of the Mummers Parade held every New Year’s Day in Philadelphia. He had also painted many portraits throughout his career, including self-portraits, and after his diagnosis almost all of his work was concentrated on self-portraits. As The Lancet authors note, his self-portraits subsequent to diagnosis “reveal a change commensurate and consistent with the deterioration in his cognitive stage.”3 They point out that self-portraits have been considered by many observers to openly express “a variety of states of mind including terror, sadness, anger, naked pain and resignation.”4 There can be little doubt that themes of sadness and anxiety are readily apparent in Utermohlen’s later self-portraits, and even terror, one would surmise, especially in Head 1. It is noted that such themes can readily be found in several of the works painted before any noticeable decline had taken place in Utermohlen’s artistic ability. One such picture, painted at the age of 60, shows the artist seated at and gripping onto a table beneath an open skylight. His wife believes that this picture depicts fear and isolation. When asked if this is a reasonable interpretation of the work, the artist himself indicated to his doctors the open skylight and said, “Yes, and I was getting out.”5

The pictures make it dramatically evident that Utermohlen’s processing of spatial and perceptual information had declined greatly, making the portraits remarkably poignant for viewers, and quite possibly raising anxiety and fear for them, perhaps even for their own futures. The Lancet authors note that because Utermohlen used an abstract style for much of his painting, this may have provided an outlet for his continued artistic expression long after his mind was no longer functioning fully, because no restrictions were imposed by the demands of realism, with its need to reflect as accurately as possible what appears before one. They conclude that to be able to continue as an artist at a stage when Alzheimer’s disease has “blunted the craftsman’s most precious tools offers a testament to the resilience of human creativity.”6 These paintings also indicate that there may be many avenues, as yet only beginning to be explored, that suggest ways in which humans can perhaps be protected from the ravages of this condition by means of lifelong social and cultural activities. Such practices will not inhibit the eventual development of dementia in people who are heavily predisposed, but they may thwart the condition for years.

Figure A.1.

Self Portrait with Cat, pencil on paper, 1995, by William Utermohlen. Reproduced with permission from Galerie Beckel-Odille-Boïcos.

Figure A.2.

Broken Figure, mixed media on paper, 1996, by William Utermohlen. Reproduced with permission from Galerie Beckel-Odille-Boïcos.

Figure A.3.

Mask (Black Marks), watercolor on paper, 1996, by William Utermohlen. Reproduced with permission from Galerie Beckel-Odille-Boïcos.

Figure A.4.

Self Portrait (With Saw), oil on canvas, 1997, by William Utermohlen. Reproduced with permission from Galerie Beckel-Odille-Boïcos.