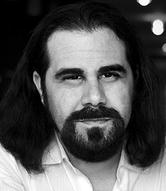

Ian Bogost

Ian Bogost and Gerard LaFond cofounded Persuasive Games in 2003 to create video games that persuade, instruct, and engage. That same year, the duo made their mark on history, creating The Howard Dean for Iowa Game—the first video game commissioned for a U.S. presidential campaign.

Bogost and Persuasive Games have continued to move the video game industry in new and exciting directions, pioneering games as editorial content for the New York Times and using video games to address critical issues, such as airport security, clean energy, and tort reform.

Dr. Bogost is the Ivan Allen College Distinguished Chair in Media Studies and Professor of Interactive Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology. A satirist, sometimes critic, and ambiguous Twitter personality, Bogost appeared on The Colbert Report in 2007 to celebrate how video games can make a difference. He is the author of several books, including Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames.

Since this interview was conducted in 2013, Bogost has continued to write and speak about games, media, and other subjects through, among other work, his role as a Contributing Editor at The Atlantic, the author of How to Talk About Videogames, and a editor of the Platform Studies series from MIT Press and the Object Lessons series from The Atlantic and Bloomsbury.

Ramsay: You’ve led a distinguished academic career. You’re a professor, public speaker, and a prolific author. Why video games?

Bogost: Right. I have degrees in areas that seem to have nothing to do with making software or video games. I got my undergraduate degree in philosophy and comparative literature, and then a master’s and Ph.D. in comparative literature.

Comparative literature is one of these fields that doesn’t mean anything to anyone who doesn’t know what it is already. It doesn’t really matter what it is, other than to point out it’s one of those areas where people mix stuff up. While I was in school, I was also working in industry, and I had other bizarre working experiences, from software development to financial services, and then design work, and print and digital publishing.

I teach now in a program where our students do this deliberately. At Georgia Tech, I teach computational media, which is half computer science and half liberal arts. That’s awesome. When I was in school, you had to make a choice between being an engineer or a humanist.

I was always interested in bringing those worlds together, more than they already were. Games are good examples of computer media that naturally fits at the intersection point between computing and culture. In an interesting leap of faith, I finally quit my full-time job and committed to two things: finish my Ph.D., and create a game development studio, to see what paths those might open up. It was like a hedge. Either I can do game development professionally, or I can do higher education professionally. Of course, I ended up doing both.

Ramsay: How did you get started with the studio?

Bogost: I had worked together with my business partner and cofounder, Gerard LaFond, in technology consulting and development during the dot-com era. Gerard also has an interesting background. He was a philosophy student as an undergrad, and then got an MBA before becoming a general manager at CitySearch.

We worked together building software for e-business, consumer packaged goods, automotive, and entertainment at a boutique agency at the end of the first dot com era. Gerard ran business development, and I was running the technology group. We had done a lot of marketing, development, e-business work, and some games, like licensed add-ons for films. Probably the biggest was the online development work around the launch of the first Spider-Man movie for Sony. We worked on huge e-business projects for the Honda Motorcycle Division, and we made some games that were tie-ins for Hollywood films. We did a lot of work for Columbia TriStar in those days. Gerard was trying to bring in business. I was trying to make the promises we had to make things we could actually accomplish technically and within the resources that were available. This is how things work in that business, right? You try to find the friction point between what you need to say to get work and what you can drum up as a solution to the problem at hand.

We had a good working relationship. We seemed to be on the same page about doing something bigger, or at least more meaningful, than just solving other people’s silly marketing problems. Since we both had worked extensively in advertising and marketing, very near the start of the studio, we thought if we built a base in advertising work, we could use that as a springboard from which to build the studio, and then move into other domains, like education and politics.

After we started in early 2003, the opportunity to create a game for the Howard Dean presidential campaign arose. It’s hard to remember now, but that was the beginning of online grassroots political outreach. A lot of people were online, especially on broadband, for the first time. The idea of the blog was new. It was a different era. It was pre-YouTube, pre-Facebook, and pre-Twitter. And this was an interesting first public project. Everyone knew about Howard Dean. It was also the first time there had been an official US presidential candidate video game. That was an interesting way for the studio to come out of the gate. We built that game together with Gonzalo Frasca’s studio, Powerful Robot, with next to nothing. In a very short time, we got the game out right at the end of the year.

Ramsay: Did either of you have experience with starting companies?

Bogost: I had not, at least not in a meaningful way. I had set up business entities that were working on smaller projects. Just before Persuasive Games got started, I got involved in an educational publishing venture. That’s a company that still exists; it’s just in a very niche publishing market. I knew what it meant to set up a company and how the basics of that work. I also had set up a previous company just for consulting work, but nothing that we thought might have a big future. I don’t think Gerard had been involved in starting up new ventures. He had a lot of experience starting up new divisions and new offices within CitySearch as they were expanding rapidly though.

Ramsay: You invested some of your own money. How did you manage that risk? What did you expect would come of your investment?

Bogost: I just assumed the funds were sunk. I could take a modest amount of funds, and throw them away without feeling like the loss would be catastrophic. This was going to be an experience that might have an upside, but I wasn’t banking my future on it. At the same time, once I quit my marketing job, something had to happen. Persuasive Games had to ramp up and provide something approaching a proper income, or I had to get a job in academia. If we had lost everything, that would have been okay. We hoped though that the business would turn into a viable entity that sustains itself.

Ramsay: You didn’t put together a business plan?

Bogost: Not even remotely. I had done that before. I put together a business plan and sought funding for the publishing business. I even toyed with starting up a web business. Before the blog was a big deal, I had an early build of software that provided blog-like services for families. I had a half-developed product and tried to build a business plan for that. I poked around, seeking money. I just found the whole experience boring and soulless.

I didn’t want to be in business that way. I didn’t want to have a “startup,” to have a “company,” or to have a set of meetings with PowerPoint slides or whatever. We had a good sense of what we could accomplish by modeling our business around a combination of service work. When we had enough experience, we didn’t feel like writing it down in greater detail would benefit anyone. Plus, we weren’t looking for external funding, so we never had to prove our salt to anyone else. And I’m terrible at trying to make my ideas match other people’s expectations.

Ramsay: Were you on the same page with Gerard about how to start up?

Bogost: Oh, we were both looking to make money and to do something interesting. Over and above anything else, we wanted to be on our own. And we were aware that we had to set our expectations at a level we could actually meet. Our time didn’t cost us anything. There were opportunity costs, I guess. And we thought, “Well, we’ll give this a shot.” When we did the Howard Dean game, we got a large amount of attention right away—a lot of press.

But more than the money, which was small, we had cracked open something that might have a future in spreading the gospel of how games can be used. That’s almost what the company has always been. We’ve made money doing this. We haven’t gotten rich doing it, but we always had this secondary mission of just trying to do our part, showing how games can be used outside entertainment.

Ramsay: Were you working in academia yet then?

Bogost: I wasn’t working in academia at the time. I had been working in tech still, making good money, but I was just sick of it. It was awful. For years and years, I had been working too much and on other people’s stuff. It wasn’t very gratifying.

Bogost: I was married. By then, I had a three-year-old, and my daughter was under one. I was almost never around though, and my son remembers that; he was old enough. But my daughter doesn’t have any real memory of those days when I would be at work all the time. Now, almost a decade later, I’m just around all the time. Since I’ve been working at my own company, and in the very unusual circumstance of academic life, I do a lot of work, but I also have a lot of flexibility in my schedule. That was a big factor in trying to rebalance my family life.

Ramsay: When did you become a professor?

Bogost: About a year after starting Persuasive Games, I got the job at Georgia Tech. We were in Los Angeles before, and we moved the studio to Atlanta. I wasn’t terribly fond of the idea of becoming a university professor. I imagined I would have to do what I had to do as a student, which was kind of lie, cheat, and steal to get away with studying and writing about the things I wanted to. I was very ambivalent about what was going to happen next, but I was also totally confident that if something went wrong, I would be able to get a good high-tech, games, or entertainment industry job and everything would be fine.

The studio predated my coming to the university. Luckily, because Georgia Tech is very encouraging of entrepreneurship and outside activities within the boundaries of our employment agreement, they were totally fine with me living in two worlds. And those worlds have definitely been incredibly, mutually beneficial. In some ways, any attention I get commercially benefits the university, and my credentials, the Ph.D., and affiliation with a major technical research institute lend credibility to the work we do at the studio.

Ramsay: Why did you take a job at Georgia Tech?

Bogost: The job presented itself. It was an opportunity that was unusual. I had told myself that I wasn’t going to take a university position unless it was right, unless it was really a good opportunity. Professionally, the job would have to allow me to really work on the intersection of culture and computation, particularly in the context of games. Georgia Tech started these degrees in digital and computational media at all levels, so there was a chance to really do the work I hadn’t been able to do as a student, and to be a part of building a program that I might have benefitted from if I had access earlier.

Ramsay: Beyond the Howard Dean game, what did you envision Persuasive Games doing? Did you imagine it’d just be you and Gerard against the world?

Bogost: We never talked much about growth in the early days because we were really trying to keep lean in order to fund projects. We were really trying to get something back out of the company, too, because we weren’t spending other people’s money. We really needed to see some income immediately, so we tried to remain very, very small and agile—and then we just became very fond of that. I think, partly, it’s because Gerard and I are not the world’s best managers, and we had been working remotely anyway. Even ten years ago, it was so easy to work from almost anywhere; that gave us the freedom to have family lives.

And we weren’t after the self-gratification of having a logo on the wall, or the validation that comes with looking like a real business. We just wanted to work on cool things. And working on cool things turned out to be pretty easy at the time. We were able to be competitive and scrappy, and we got a lot of attention which brought more attention which brought more opportunities.

Ramsay: Did you hire out the engineering work?

Bogost: I can program. I do a lot of work on our games. We do hire out though because I don’t want to work on the games all the time. We’ve done that partly by having a small number of employees during our boom years, and often by just bringing in people we work with on specific projects.

I think we would have never done our most interesting work had we tried to build a small- to medium-sized business quickly. We would have gotten wrapped up in our run rate, we would have had to go out and find ways of sustaining that rate, and then we would have definitely been responsible for those mouths we had to feed.

Ramsay: You know, Persuasive Games doesn’t sound a typical studio.

Bogost: Is there a typical studio anymore? Our studio has always been a hybrid between a services organization doing game development on behalf of other companies, and a small, independent studio. The business really got off and running right when the services model and serious games were compromised by the financial collapse of 2008—just before the distribution channels we now take for granted had really arisen. Our timing was a little bad in that regard.

Before then, it wasn’t really possible to make money on small-scale, downloadable or online games. We had a little ad revenue, but we didn’t have the downloadable and mobile channels that are available now. So, the idea behind the studio from a business perspective was always to stay independent and bounce between a combination of services revenue and independent sales.

If you look at a company like Area/Code, which became Zynga New York, they were doing similar things: a lot of advertising or entertainment work-for-hire deals, and they were slowly developing a stable of their own games, too. They managed to hit that peak at the right time to be acquired, although that didn’t necessarily work out the way they’d hoped in the long run.

Often, the services work we do never sees the light of day. Consulting is interesting because it gives you a chance to see a lot of different problems. It’s also sometimes frustrating. Shipping games is much more appealing than just solving hypothetical problems, or telling people to not make games, which is what we spend a lot of our time doing.

Ramsay: Do you work with publishers or self-publish?

Bogost: For most of our work, we’ve either distributed it ourselves, or it’s been published in a very particular context. For example: games meant to be distributed through after school programs or implemented in a corporate Internet training system. For our own original work, we’ve both self-published and worked with publishers.

Ramsay: Did the Howard Dean game fit with your vision?

Bogost: One thing that’s interesting to me is that games can be used for lots of things in addition to entertainment. It stands to reason that the ways of developing, publishing, marketing, selling, and using those games are just as varied.

This is fairly obvious when you think about other media. If you worked on commercial and fine art photography, like taking portraits for magazines or photographing food for Gourmet, the processes and methods of working would be different from managing your portfolio for gallery installations and fine art sales.

With TV and movies, the moving image is a general purpose medium you can use for big blockbuster films you see at the cinema. But you can also use the moving image to make little instructional videos to post on YouTube, or that play when you get on the airplane to tell you how to buckle your seatbelt.

We’re often working in modes of game development that are different from the commercial entertainment industry, so our relationship to the business of games is more complex. With that said, we occasionally work in the ordinary entertainment game space. In those cases, publishing has less to do with methods than with the compatibility of our games with the interests of the marketplace.

Ramsay: Did Howard Dean’s campaign managers come to you?

Bogost: I got introduced to one of their campaign advisors around the late summer or early fall of 2003. We talked about doing the game, and they were immediately on board with the concept.

Ramsay: Has buy-in always come that easily?

Bogost: Oh, god no. That’s always been the hardest thing when working with organizations that aren’t familiar with games: getting them to buy into the value of games. I would say, generally speaking, the most common issue we’ve had has been comfort and commitment. The problem is not even the idea; a lot of folks are interested in making a game, even if they haven’t done it before.

The problem comes when they realize what that actually means—that, no, we’ll actually make a video game and they’ll release that game and people will play it. At that point, it’s often very startling to our clients that this is actually happening. Where we’ve had the most success is when someone high up in an organization has endorsed not games specifically, but the idea of experimentation and taking risks with new things.

And where we haven’t had success, that alignment has been absent. The typical issues are very boring. It’s not so much about people’s misconceptions; it’s more about their aversion to risk in their jobs. If you’re a brand manager at a consumer goods company, or the editor of a newspaper, you have a lot of work to do. People like that just want to go home at the end of the day. They don’t want to stick their neck out for something that might not be worthwhile.

For instance, we were working with the New York Times doing newsgames—games as journalism—back in 2007. Our editor was well-meaning, but they just didn’t want to try this new stuff in a way that would allow us the freedom to experiment and figure out what it meant to make games about news issues, and to do them quickly. They were overworked, concerned, and no one was rewarding them for these experiments.

Ramsay: When you meet with prospective clients, do you try to figure out what they need first? Or do you instead start with the game you want to make, and then find someone who needs that game made?

Bogost: It’s happened both ways. The way we run the business? More of the former. We have a lot of interests and enjoy working on a diverse set of problems. Occasionally, if we have the resources and the wherewithal, we’ll make a game we want to do. But in other cases, one of the interesting things about the consulting model is that you get to see a lot of different problems that you wouldn’t have encountered otherwise, and try to help organizations solve them, even if in a small way.

Ramsay: How do you go about developing a game around an issue?

Bogost: It’s actually a pretty straightforward process for me. Think about what games are; they’re systems you interact with. The games we make are about real-world systems. If we want to teach someone how to do a job or represent a political issue, we make a game that shows what it’s like to be somebody working in a job, or one that characterizes the complex choices that arise when you allocate resources in a civic context. And through these games, you find there’s not one way to do things.

We’ve done corporate learning games—games for employees to play as a way of either practicing or learning their jobs. We’ve done this for line workers in retail and food service, and general managers in hospitality. In those cases, one way to get a sense of how a real-world system works is just to go into the business and do the training. I did the new employee training at Cold Stone Creamery, for example, and we did the same with hoteliers. And we’ve had to do research on more abstract topics, like a pharmaceutical or chemical process, a set of civic or political issues, or a particular legislative proposal. We have to either learn enough so that we feel like we have a good understanding of the model, or work with experts who know more than we do.

The first step is to learn about the system we’re modeling, and then get an angle on that system. What are we trying to say about it? Are we trying to just depict how it works? Or are we trying to make an argument about it to say there’s a solution we would like you to consider? Are we trying to advocate for a particular course of action? Should you take this next step in your political life? Or should you buy this product? That’s the second step. What’s the argument? We try as hard as we can to get our partners to tell us what they’re trying to do, what problem they’re trying to solve, and why they want to make a game.

Ramsay: With entertainment games, you measure success by sales. Since your games tend to be communication media, how do you measure their success?

Bogost: In most cases, our clients are interested in getting an idea across, altering a set of possible behaviors, promoting a product or service, or providing some version of what they do in a different way. Measuring the success of such initiatives usually involves the tools that you use to measure marketing of any kind: the number of visitors, or players, or the amount of plays, or the popularity of a game, particularly if you’re giving it away. You can use these as stand-ins for sales.

When we develop corporate learning games, we look at whether we can get employees to play these games of their own volition without any reward. When they play those games because they’re useful, we’ve been able to show that engagement is much higher and lasts longer. The employees talk about and engage with the material in a way you can’t imagine with other training options.

Ramsay: Do your games tend to be naturally pedagogical?

Bogost: Some of our games are pedagogical. They’re trying to get something across. Others are really quite exploratory. They may not look it on the surface, they may not sound like it, but they represent the operation of some system. They don’t have a specific conclusion or action. Often our games really just show the dynamics of something—the conditions under which something operates.

We made a game a few years back about creating clean energy through wind farms, but we wanted to demonstrate the political issues involved. For example, one problem with wind energy is that out in the country where there’s enough consistent wind conditions to put up a turbine farm, people just don’t want them there. They don’t want their view or pastoral hillside disrupted by these big, ugly turbines. So, it’s not so much that we have an opinion that we’re presenting—that we think it’s right or wrong to pursue a particular energy strategy—but that we wanted to show that this dynamic is at work and worth considering.

Ramsay: When players say “that game sucks,” they really mean the game wasn’t fun, and not everyone enjoys the same games. With a corporate learning game, does the game have to be fun for the game to be successful or effective?

Bogost: No. It’s a terrible idea for these games to try to compete for the entertainment time of their employees because then the game has to be interesting and it has to not suck, right? What that typically means in a business context is that the game must earnestly engage with whatever aspect of the business it deals with. That might mean explaining and characterizing some aspect of a job; providing helpful, useful practice so that an employee knows it better; setting up the context in which they’re working; or enabling them to practice the skills associated with that work or what have you. That’s different from being fun, right? It gives you a deeper knowledge about the job that you do.

And you might call that gratifying. It’s actually really gratifying for employees, especially public-facing service employees who are working on the line in big organizations. It’s very gratifying to understand why the hell they’re doing the things they’re doing. It makes their job feel less arbitrary and more meaningful. But it isn’t necessarily fun. A job is a job. Treating the job seriously, not trying to trivialize it as an entertainment experience, gives it more value, not less.

Ramsay: I’m sure you’ve read Raph Koster’s book, where he argues that fun is learning. Would you agree with his conception of fun?

Bogost: Raph and I talk about this a lot. He and I are closer than ever before in our conception of fun, but my problem with his idea is that it’s too cognitive. His idea of fun is too much about this quasi-neuroscientific analysis of what fun means. For me, this practice of discovery, of learning something new or deeper about something, does seem to be intimately tied to what we call fun. And even in entertainment games, we find them fun not because they’re distracting or amusing, but because they give us a system to explore. When we explore that system, we find gratification in finding new parts of it, or returning to familiar ones.

I’m skeptical that fun is a cognitive process. The idea that fun is learning puts too much of the work—or too much of the success of that work—on the player. This is where Raph and I disagree, I think. He’s very much of the opinion there’s this co-creative process of equal contribution from player and the game. Obviously, you need a player experience to have an emotional response to it, but to me, in large part, the fun in a game is in structuring it so that the play space it creates is compelling, rather than that the burden is placed on the player to feel a certain way and then just to measure the nuance or quantity of that feeling.

A subtle distinction, but I think it’s one of the differences between Raph’s thinking on fun and mine. For me, fun is where the action is whereas, for Raph, the player’s experience is more prominent.

Ramsay: As communication media, your games have to engage players in a conversation, but a conversation takes at least two.

Bogost: Yeah. The danger in the games I make is they have to invite a player to experience a topic they might not otherwise have cared about at all. When you buy a Grand Theft Auto game, what are you getting? You take it home, you play it, and you have a set of responses to it, but you knew you were already interested. You had to pony up some money to get what you expected.

If I give you a game about wind energy, or your otherwise forgettable job, I can’t rely on the idea that you’re coming voluntarily to the game with open arms. My audience is always going to be a little suspicious. At the same time, players have to be open enough to the material such that I can meet them halfway.

Part of this idea of opening a conversation is just “hey, I’m going to prove to you that the thing that I made a game about is worth it, that it deserves having a game about it, that it’s not silly or a gimmick or a joke to make a game about ice cream portion sizing or about the features of this new SUV.” I think that can be done for anything. I don’t think there’s a set of topics for which it can’t be done.

Ramsay: How do you build progress tracking and evaluation into your games?

Bogost: It’s a lot of soft measurement, like whether a player has demonstrated an ability to synthesize the ideas inside the game into a little nugget of wisdom. And then it’s up to them to act on that wisdom. That part you never get for free. The idea that you can put a piece of media of any kind in front of people and then, magically, their behavior changes? I just don’t believe it. I don’t think it’s possible.

Ramsay: You’re quite widely known as a vociferous critic of gamification. Why do you hate gamification so much?

Bogost: It’s a lie. It’s snake oil. It’s a way of making the promise, the appeal, and the sexiness of games feel like games can be easily tamed and put to use in business without actually doing the work of putting games to use in business. It’s a type of consulting pretending to use games as solutions. Gamification is just a perversion of behaviorist economics.

In relation to game design, gamification has little to nothing to do with it. In relation to business solutions, gamification isn’t necessarily about solving any problems. All gamification developers care about is providing consultancy services to organizations that want to get in on the game of getting in on the game of games. The difference between making games and gamification is the difference between cooking and driving. They just have nothing to do with each other.

Ramsay: Quite a visceral reaction, but you’re a professor. Taking an objective position, studying every dimension of the problem, why is gamification not a lie? Why is gamification not snake oil? Why doesn’t gamification work?

Bogost: The argument I’m making about gamification is largely one that has to do with the rhetoric and presentation of the material. There are these management trends that come and go. When they come, there’s always somebody there to capitalize on them, to oversell them, to build conferences around them. The argument I make about gamification has nothing to do with the output of the gamification business. The gamification business seeks to produce a commodity to be sold in the same fashion to everyone as a general solution, that works in all cases, at a low cost, with a high reward, and then to strip mine that interest until the trend burns out and the next trend comes along.

So, the idea that there are specific examples of incentive-based reward programs that have results, that can demonstrate results, has nothing to do with gamification. Gamification completely fails to acknowledge its predecessors in business intelligence and incentive programs, and just gives lip service to these things. But at the end of the day, gamification is really just sugar water; it’s a gloss that you paint over the existing practices that you’re already doing. Adding a little bit of slightly game-y incentive-based applications to them in order to make it appear as though you’ve ticked off the box of a video game strategy within your organization.

I’m very cynical about this because the values gamification represents as a way of engaging individuals with a business is just repellent to me. Gamification is like saying we can get people to accommodate our wishes when we take them hostage and threaten their lives. I don’t think there’s a reason to justify that behavior.

Ramsay: Hostage taking works, I guess. Does gamification?

Bogost: Well, gamification works, insofar as the purpose of gamification is to get organizations to buy gamification services. That’s the point of gamification. It works pretty well at that. Whether it works in the business contexts it’s deployed in is completely irrelevant to the gamification world. They need enough examples that seem to be reasonably coherent, such that they can point to them as case studies.

But the truth is that even the people who are buying these things, they don’t really care if they work or not; they’re buying them so that they can keep up with the corporate Joneses. Gamification has established itself as a trend you’d better be talking about when you’re a brand manager, HR manager, or whatever. When your boss asks you, “I’ve heard about gamification. Are we doing that?” You have to say, “Oh, yes. We’ve investigated that. In fact, I’m attending this conference…”

Ramsay: Supermarkets have been using loyalty programs for a long time. To me, gamification applies the loyalty program model to other problems.

Bogost: The loyalty programs in supermarkets aren’t really loyalty programs. They’re more like hostage situations. Basically, the supermarkets say, “Hey, I’ll make you pay a worse price on our products unless you give me data associated with everything you buy.” You use those cards, so that you can be tracked by supermarkets, who then build complex databases of purchase patterns.

Real loyalty programs provide a way for customers and businesses to talk about what they value and what they want in return for the value they provide. Real loyalty is bidirectional. You can’t have real loyalty if it only moves from the customer to the organization. Gamification doesn’t create real loyalty because it’s just trying to trick or fool people into doing something they might not if they really understood what was happening.

That has been going on for a long time, and that is by no means exclusive to games or loyalty programs. We’ve debated endlessly about whether tricking people into doing things they might not do is a virtuous business practice. In the past, we admitted they’re tricks; we didn’t glorify them as entertainment experiences. We ought to admit now and again that gamification is that same kind of trick, where a business is just trying to dupe you out of your money and your dignity.

Ramsay: Moving on, your games don’t have a specific conclusion or action, but how do you have a game that doesn’t have an end?

Bogost: If we were dealing with workplace safety, customer service, the assembly of a particular menu item in a restaurant, or what have you, you want to understand how they work or practice to get better at them. So, the ending of one of our games is not so much a place and time when you’re done. Instead, you’ve played through the missions or the levels or something, and you feel like, “Okay, I’ve got a sense of this system. I have a sense of how this works in the manner that it’s been presented, and that’s something I can return to in my mind later. That these are the dynamics that are at work in a particular situation.”

Ramsay: Some would call that point where the player expresses their understanding “grokking the pattern.” As a designer, how do you know when players have reached that point?

Bogost: One method of understanding that pattern is recognizing that it’s incomplete. You see that it’s just one piece of a larger puzzle, and it has to be reincorporated into a set of other practices, whether those are exercised through games or not. People sometimes think they want an answer, like “just tell me what to do, and I’ll do the things right.” But the thing that’s right to do varies and part of what a game can offer is a sense of that variation: that any general rule has to be altered, mixed, or blended into other varied circumstances.

What we end up doing in life is taking little bits of knowledge and reassembling them in ways we’ve never seen before, or ways we’ve seen before that have slight variations and those variations end up mattering a great deal. So, part of grokking the system also involves being able to see the limits of the system you’ve grokked and the places where the system breaks down.

Ramsay: Do your games try to capture that point where players see where the system breaks down?

Bogost: I think they try to be honest. They don’t try to over-portray the wisdom they are passing on, sometimes through humor or visual abstraction. In a corporate learning context, there’s some really boring but serious matter-of-fact instruction and information dissemination that has to occur. The challenge that we face is to rise above the noise and give players something memorable. I think one of the reasons we use these sort of cartoon-like scenarios is to acknowledge that we’re not capturing everything, that we’re abstracting the real world.

Ramsay: Do your games test whether player have internalized that wisdom?

Bogost: I really don’t think you can do this. I think what you can test in a game is whether a player has understood the game. A game can test whether the player is good at playing the game, but that’s all it means. If you want to talk about the experience they had in the game outside of the game, then that has to take place outside of the game, right? You have to reflect and discuss. That’s why I’m so obsessed with discourse analysis; of looking at the ways that people talk about the experience they had in a game in relation to what they know or what they thought they knew about the topic. That’s where I look for synthetic evidence.

But there are a lot of folks who think, “I’ll just plug this into my learning management system, and ask a series of quiz questions.” You’ll pass that module, and you’ll be certified in whatever aspect of the training regimen you’ve been asked to be certified in. All that stuff reflects only the player’s performance in the system. It doesn’t have anything to do with their ability to put their new wisdom to use.

Ramsay: If the game can’t provide that feedback, do you need someone in the room to pull them away?

Bogost: I think one problem with this work is that often the framework for that feedback isn’t put into place. Some games we make are played in a very specific context. For example, there’s a management retreat for general managers of hotels in a particular hotel chain. This is a real scenario we’ve done. It’s facilitated by instructors, and there’s a small number of participants who do a wide variety of activities, including play a game. They play the game, they discuss, and they play the game again, looking at it differently. And the game becomes an experience they can return to at home. But I think, by and large, this doesn’t happen enough.

Ramsay: You’ve said that you run a small business.

Bogost: It’s definitely a small business. I don’t even know that there was a time in my life when I was comfortable using the word “entrepreneur” for what I do. I’m now totally, just completely, disgusted by that term. It has been so invaded by the startup world.

We provide a set of very custom solutions, and we also make our own games. We provide a very boutique service. It’s the kind of company venture capitalists would derogatorily call a “lifestyle business”—a thing that can’t possibly grow, doesn’t want to, and is therefore corrupt because it’s not trying to scale to a billion dollars as quickly as possible.

We have a small business. It’s a small business that comprises a portion of our incomes as partners. We’re doing what may not ever be work that can be done at a large scale. I’m not bothered by that. It’s an interesting and challenging set of problems that has allowed me to see a variety of little corners of the world I wouldn’t have been able to see otherwise, to make some weird and hopefully interesting games. And these are games that have had a modest impact in a variety of different contexts, that have been gratifying both to make and see played, and, in many cases, have been ungratifying to see made and not played.

A lot of our business is telling people to not make games, by the way. “Please don’t make a game. It will do you no good.” Sometimes we get paid to reach that conclusion, but I find that to be just as useful as a conclusion that results in me making a weird game.

Ramsay: Well, telling people to not make games doesn’t sound like a very sustainable business model for someone who makes games.

Bogost: It is sustainable because it’s not a lie. I think our reputation matters. We don’t just make games because someone knocked on our door and said, “We’re willing to spend some money.” We want to make the games that ought to be made, not just any game that could be made. It’s maddening and just completely demoralizing to me to work on something that shouldn’t exist, or to work on something because there wasn’t anything better to do. I just don’t want to do that.

Ramsay: How small is a small business?

Bogost: How do you measure businesses these days? I think the ways we measure businesses are stupid. Do you measure businesses by revenue? Do you measure businesses by the number of employees? What do we measure businesses by? We are a company whose permanent staff is two and whose typical staff is about three to five. We bring in a small amount of revenue every year. It’s a strange thing to have to justify, right? You’d never ask somebody the opposite question like, “How big is a ‘big company’? 10,000 employees? 50,000 employees? That big?”

Ramsay: I think I would, actually! I know you’re working a few jobs in addition to Persuasive Games. Would you be able to quit those jobs and make games full time?

Bogost: We could do it. I couldn’t do it and maintain the same lifestyle I currently have though. It would be different. It would be possible to sustain a living on this work for sure. But I’ve also scaled it down partly because I don’t have to rely on it year over year for my personal income. That looks like it’s completely ridiculous, unsustainable, and not repeatable. I actually think this is a pretty common pattern for small businesses these days, where you’ve got a little thing and that little thing does a certain amount of work for you. Maybe it’s not enough to sustain your whole family, but it’s one corner of your life.

Ramsay: You don’t aspire to “make money while you’re sleeping”?

Bogost: In this particular business, if we were to do that work, it would be through original work rather than client work. A lot of the original work we did early on was a little bit early in mobile location-based games, news games, and weird political games. We had unfortunate timing in getting a lot of stuff to market when there weren’t any distribution channels.

But even if you look at app store-style game development, it’s hardly a sure thing. There are very few individuals or small businesses that sustain themselves on that work because you’re charging 99 cents for a game. Well, either that, or you have one of those free-to-play monstrosities that tries to extract enormous amounts of money by virtue of advertising and network effects. Everybody wants to make money while they sleep, but that would be a different business for us.

Ramsay: How would you say you’re different from indie developers?

Bogost: I think we share a lot in common with indie developers. We do independent development. We also do development for other people and organizations. Some indie developers do this, too. They’ll do consulting or freelance work, and then they make their own games. In that respect, we have a lot in common. But one difference between us and the indie scene is that there is a lot of indies who are young, up-and-coming twentysomethings who have all the time in the world to just make their game. They can live on a shoestring budget and do their thing. I think that’s awesome. I wish I could do that, but that’s not what we’re doing; we’re at a different stage in our lives.

Ramsay: In much of your work outside the studio, you’ve become a captain of mockery.

Bogost: There’s definitely a large percentage of my work that is satire. There has been some of that work at Persuasive Games, too. We did this weird game that was a mockery of Kinko’s business practices. I like humor. I like satire and parody. It’s a very serious business actually. There’s a gravity to humor, particularly black humor. Satire has never been at a higher fever pitch. The fact that people think of Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert as serious journalists when they’re really comedians is because the news business is in such dire straits that their mockery feels more real than the reality. Satire is a very serious way to communicate ideas.

Ramsay: Isn’t satire also a safe comedy?

Bogost: There’s risk in satire. If you mock everything in the same way, then it becomes meaningless. It’s precious. It can’t be used all the time. I think in that respect, it’s a little too easy to do send ups and mockery when in some cases a more serious approach to a real issue is recommended.

All that said, I think that there’s plenty of room for more humor and more satire in games than we’ve seen. Humor is not as common in games as it is in other media. A lot of the games we think we love for their seriousness we actually love for their humor. We’re talking today, the day before the release of Grand Theft Auto V. That’s a good example of a series that’s incredibly satirical and snide, but which also has this gravity that people mistake for seriousness.

Ramsay: You also use Twitter for satire as well.

Bogost: My Twitter persona is very ambiguous in that regard. I think a lot of people are not sure if I’m straight-faced. I love that format where anything might be either exactly what it says or just the opposite, which is the way I feel about the Internet in general.

Ramsay: When you were promoting your book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames in 2007, you appeared on The Colbert Report. How did appearing on that show affect your business?

Bogost: Obviously, any attention is attention that pays dividends. If somebody hears about my writing and they work for an organization that might want to make games, they start to look into who might make games for them and they’ll find my name. That has some direct benefits. The indirect benefit is I really am interested in this stuff. I’m committed to the results, not just the money.

Potential clients often ask, “How much will it cost for you to consult for us?” I often answer “twenty bucks” or whatever the cost of my book is at the time. I’ll say, “Just go buy the book. The book won’t give you a personal solution to your specific problem, but all the approaches are in there. Have at it.”

I think by giving these ideas to the world and simply inviting everyone into the conversation rather than thinking everything needs to be owned and tightly controlled, that every exchange has to be under NDA and I have to bill every hour of my time, well, all that stuff is a little weird to me.

Ramsay: The path to success for many people involves building up and out.

Bogost: We’ve had those thoughts. We’ve worked at larger companies in the past. We had large teams. We were part of those organizations. We had that experience. But we didn’t have that sense that “oh, this is what a company is. I want to build a company that has this many people.” If anything, we didn’t want to deal with the difficulties of worrying about making payroll, keeping everybody afloat, and having enough business to sustain the company.“ But we’ve talked about it in the past. Mostly, we’ve talked about taking investment for various projects because, at that point, you’ve got to be all-in and ramp up fast. Certainly, one of the reasons why we’ve never done that is because we just didn’t want to be forced to run the company according to somebody else’s desires.

Ramsay: You’re satisfied with just profitability?

Bogost: I don’t know what it would mean to be satisfied with anything. I’m satisfied with some of the work we’ve done, and with some of the what I think are influential contributions to a variety of fields. That’s where I find the satisfaction; it’s not really in the business part. That’s nice, but that’s just gravy for me. Satisfaction to me is really the feeling of having accomplished something in the world that I’m interested in.

Ramsay: When I talk to founders of large enterprises, I always ask them about quality of life. For them, quality of life often comes down to free time. But you seem to fill up your time as much as possible.

Bogost: I have a lot of friends who are in that situation; they’re running large companies in various industries. I think everybody’s got their own ups and downs. I’ve got to do a lot of wrangling on my own. We don’t have as much stuff that just takes care of itself.

I was hanging out as a game designer in residence at PopCap Games over the summer. They’re a pretty big studio that’s a part of a very large company. I had forgotten what it was like to have a kitchen in your office, where you just go in and there’s food and drink there all the time. There are little things like that, or like having someone take care of accounting. Sometimes I wish I just didn’t have to deal with every little detail. And then, of course, at Georgia Tech, I have a handful of students who work for me; it’s like a small research organization. I have to keep them fed, manage what they’re doing, meet with them, and make sure that everything is going according to plan. That takes up time, too.

If anything, if I could imagine a different approach to living my life, it might involve somehow having the resource flexibility to just do exactly what I want to be working on at any moment with no demands from elsewhere. I’d like to think that if I were lucky enough at some point to have the material resources to not have to worry about work ever again that I wouldn’t invest those resources in silly things like another company. I would try to use them to figure out what I can contribute when I’m not distracted by all the things I have to be distracted by to make a living.

Ramsay: Do you ever get tired of your many responsibilities?

Bogost: Everybody gets tired of their job. I have a pretty good situation. I try to remind myself that even when I get annoyed, it’s a good set up. There’s going to be nuisances everywhere. I’m fortunate to have the ability to remember how other situations work. One of the nice things about spending some time in a large company, like when I was at PopCap, is remembering what it’s like to come into work every day. I don’t want to come into work every day, actually. I want to have a lot of flexibility.

Ramsay: I was watching Conan O’Brien interview Harrison Ford a few months ago. At the end, he said, “You’ve reached a stage in your career where you can do whatever you want.” Shaking his head, Ford lamented, “I wish that were true.” It occurred to me that no matter how high you rise, you’re always hustling.

Bogost: I think everybody’s hustling, and hustling more than they once were. And even people who work salary jobs are hustling now, too, because you have no idea if you’re going to get laid off next week. You have a suspicion that once this product is done, your team is going to be made redundant. On top of that, we all have these identities online now we have to hustle: “Here I am. I have to say something interesting today on the Internet or you will forget about me!” Even when we’re not selling something explicitly, we’re constantly hustling.

Ramsay: When you are selling something explicitly, you have to qualify to hustle. Book publishers won’t sign you unless you have a platform, for example.

Bogost: Well, while you are building a platform, speaking, and engaging, they want you to have a website where you’re talking about nonsense. It’s something that everyone has to do. We don’t do it enough because there is a cost to it. I think it’s the flipside of this golden age of independence. There never really was independence; it was just a license to have other obligations.

Ramsay: To what extent does social media impact the time you have available to your business?

Bogost: Or available to anything else? The Internet has become a destructive compulsion for everybody. It’s there to keep us busy while the Internet companies take over and destroy the universe! I feel both obligated to, and disgusted with, my relationship with these tools. You have to—it’s an ecosystem now. When you do what I do, largely hocking ideas into the idea space, it’s a place with a very short memory; you have to constantly return to it. But it’s a place with a short memory partly because we’ve made it so by filling it with all of our chatter.

Ramsay: Sometimes people try to avoid social media by going cold turkey. What do you try to do to avoid being overburdened?

Bogost: The main thing I do is I have a work computer that’s online but offline. It has the Internet, but it doesn’t have all those accounts set up, like downloadable Twitter clients, instant messaging, and all that stuff. When I know I need, or want, to be disconnected, I’ll just go there, and it’s a physically different workspace. I wish there were more of those spaces. It used to be possible on airplanes to escape, but now you can get Internet access in the air, too. There’s almost nowhere you can go without cell phone coverage anymore. All of those nooks and crannies are increasingly unavailable unless you fashion them yourself, so you have to fashion them yourself.

Ramsay: You’re definitely not a fan of gamification, but isn’t social media modeled on what gamification purports to be?

Bogost: Well, yeah, people like to count their chits, I guess. It’d be interesting to see what social media would be like if you just took all the numbers out. In fact, there was somebody who made a plugin or something for Facebook that removed the “this is how many friends you have, this is how many likes, and this is how many shares.” It definitely gave Facebook a different tenor, when you didn’t know how many followers you had, or how many times your last tweet was retweeted, favorited, or all this crap we count as if it mattered.

What if we could see something else? What else would we want to see? For me, the key is the way we’ve influenced people, or how much we’ve contributed to something bigger than ourselves. Those are things we could try to measure, if we weren’t so busy measuring the number of times we clicked on stuff, which is basically what all those numbers end up meaning.

Ramsay: Is that drive to measure our social capital really our fault? Or are we enabled by Facebook, Inc., Twitter, Inc., and other companies?

Bogost: You have an onboard computer in your car that tells you your current fuel economy, and you try to maximize your moment-to-moment driving patterns. It’s not exactly the same. It’s certainly not limited to digital technology, but it certainly is an example of this feedback system that has been around for decades. We’ve been counting stuff for a long time.

I don’t think you can point to Facebook or any specific example that started all this. The Internet has just amplified that, and allowed us to do it for everything, not just for a subset of our experiences. Maybe it should give us pause. Not so much that the measurement itself is a problem, but do we want to do it to everything? Do we want everything to have a little gauge on it?

Ramsay: Do your clients want more numbers to count?

Bogost: They often think they do. They often express that they do: “We want to increase our stickiness, or our page count; or we want to increase engagement.” That’s sort of nebulous: what does it even mean when people say that?

The number of people who click on something, or the amount of time they spent staring at your website, may or may not have anything to do with the growth of your business or there might be other values at work. But it’s an easy way to pretend that it does, so we can build a collective delusion that we have a generally accepted and scientific way of measuring stuff.

Ramsay: Along with an increasing dependence on metrics, everything has to be social, in the cloud, or whatever happens to be popular at the moment.

Bogost: Well, everyone uses the same buzzwords as everybody else does. When you point it out to them, they’re embarrassed. The best thing you can do to fight this stuff is ask, “Everybody’s talking about this, but what does it really mean? What does it mean to you to be social?” And they realize they have no fucking idea what they’re talking about. They’re just spouting back the thing they heard at the last meeting, what they think their boss wants to hear, or the thing they think will allow them to keep going another day. And usually it does. That’s the thing. Everyone’s involved in this complex game of cat and mouse where if they all look the same, they can point to the guy next door and say, “We’re doing the same thing as everyone else.” If you stick your neck out, it’s easier to be blamed.

Ramsay: Are there any games you want made?

Bogost: I have notebooks full of stuff I think I might want to do. But I don’t find the creative process anymore to be one of trying to realize some fully formed vision. It’s more of a matter of allowing a set of unformed ideas to realize themselves to a point, and then suggest a path that they follow. There are other kinds of games I would like to make, but in my current lifestyle, where I have a lot of different things going on, I have to be a little bit particular. At this stage, I’m interested in trying to make stuff I feel great about. But I do have to admit it would be nice for one of those games to also be massively commercially successful.

Ramsay: In terms of game design, have there been opportunities you missed?

Bogost: There are just tons of things I had early inclinations about that were right in retrospect but that I didn’t pursue or I didn’t pursue enough. In 2003, when we did some of these campaign games around the election of 2004, they had early social features that would later become standard in games. We didn’t have the social networks yet, but we had these ways of connecting with people via instant messaging and other mechanisms to draw them into our game. They became resources then by virtue of the fact we had reached out to them. This fit well with the notion of social outreach in the political sphere.

In 2004, I wrote pretty extensively about asynchronous multiplayer gaming. This was back in the era of World of Warcraft and EverQuest. The MMO was the way that multiplayer gameplay was thought of. Asynchronous play became incredibly huge in Facebook and mobile games.

We made a game called Jetset about the TSA and air travel. We had this whole location-based play thing where you could play in different airports, and you could get these little souvenirs related to the location you were in. That idea of checking in was around long before check-ins became popular with Foursquare.

But in all of these cases, we were too early. Even with newsgames, we were too early. They were overly complex. It turned out that what people wanted was a much simpler and shittier version of the same idea.

Ramsay: Where do you see yourself going? How many jobs is enough?

Bogost: I feel like I’ve got one job really. I don’t really feel like I have more than one job, and that one job is to think about the meaning and application of games and media more generally, in the era of computation. I do that in a lot of ways. It expresses itself in a number of forms. At my studio, there’s a particular game design we do. I’m interested in other kinds of game design and how they work, and how organizations function. I’m interested in teaching and thinking about the game design process as a practice we can refine. I’m interested in looking at individual games other people make. I try to identify and describe how they work, how they work well, or how they don’t work well. It’s all just one thing to me. It’s just that I enter that process through all sorts of doors, windows, air vents, and even holes that I drill through the wall.