14 Man and Surroundings

Photography can showcase the surface of things, as do the large portraits by Thomas Ruff, one of the world’s most expensive artistic photographers. Apart from Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, he is probably the best known of the Becher School photographers. To support his viewpoint, he takes portraits of people with a large-format camera, as if he is taking a meaningless passport photo that says nothing about the sitter’s personality. He then enlarges this “neutral” photo, to a size of almost 7 feet. You initially get the impression that it is a passport photo, but as you come closer to the image, the face starts disintegrating into its surface components. Standing directly before it, you see only a collection of pores, pimples, and other skin blemishes in vivid sharpness. The character that cannot be captured becomes nothing more than a surface when seen up close. Photographs conceived and enlarged like this do indeed capture just the surface because the nature of a person cannot be glimpsed in them.

Throughout the history of photography, countless photographers have vividly demonstrated that photography is quite capable of going well beyond the depiction of surfaces to reveal personalities. Most of the time, photographers recorded a human significance by placing people in surroundings that would say something about them.

Whereas in the late nineteeth century it was stylish to portray the bourgeoisie in their ambience, one of the first photographers who left the studio to capture people in places having a different special atmosphere was Eugène Atget. Apart from impressive character studies that don’t shy away from disreputable professions (rag pickers or prostitutes, for example), he vividly showed Paris in his portraits at the turn of the nineteeth century.

Similar successful fusions of people and their surroundings are also the trademark of the photos taken by the sensitive British photographer Bill Brandt in the early 1930s. He felt attracted to the victims of the new disease of the bourgeoisie: depression. He set out to portray the poor and suffering of his times with a lot of compassion (think of his well-known photos of unemployed miners riding bicycles to collect coal). Another one of the “Sociologists of the Eye” is the famous August Sander, who attempted to typify an entire country (Germany), structured according to the professions of its inhabitants. His best-known photo of a baker is also a fusion of a person and his everyday surroundings. August Sander even had the opinion that every profession created its own type of person, who would then be photographed by him with some attributes from his professional surroundings.

Fashion photography also dealt over and over again with the fusion of model and surroundings. Naturally, the goal was not to characterize the model with her traits but rather to attach external attributes to the model when choosing the surroundings in order to stimulate potential buyers. Often, fashion photography is criticized for its superficiality, but the history of photography proves the opposite: French fashion photographer Jeanloup Sieff developed a unique style in a powerful way. He almost never photographed his models on the catwalk but placed them in surroundings that were frequently so moody or droll that the atmosphere would almost dominate the models. He often fought it out with editors (of Harper’s Bazaar, for example) who thought that the clothing got lost in his images. Most of the time, however, he prevailed, and eventually he became one of the most sought-after fashion photographers precisely because of the way he fused natural-looking models in especially atmospheric surroundings.

A highly successful fusion of the person and personal space was the book The German Living Room by Herlinde Koelbl and Manfred Sack, published in the early 1980s. The German and his ambience were characterized across all social strata, and their work characterized that historical period as well.

In my opinion, the best fusion of a person with his surroundings can be seen in the book East 100th Street by New York photographer and Magnum member Bruce Davidson. After tiring of industrial photography, he decided to photograph Harlem. “I had to make contact with people once again in a way that not only demanded observation and commentary, but participation, a giving and taking, that allowed me to come back to myself.” He spent two years working with a tripod and a large-format camera in New York’s 100th Street and everyone quickly knew him as the “Picture Man.” He took photos for people; every sitter who requested prints was given them. The result was an expression of close participation in the lives of these people and of togetherness. His touching photographs are not images of a voyeur but of a photographer who earnestly cared about Harlem’s residents. Thus, his photos are not really pictures that expose ridicule and abuse but rather images of deep humanity that nevertheless look inside the dark side of society.

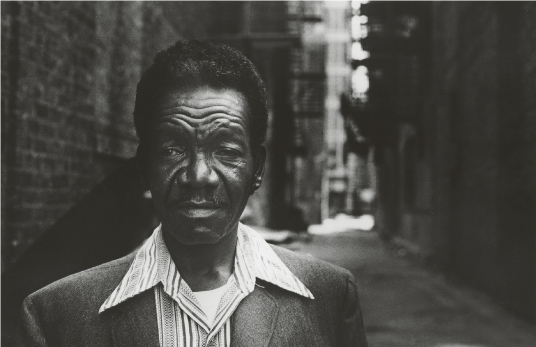

In the Shadow of the Bronx

The photo in figure 14–1 can be regarded as a small homage to Bruce Davidson. It is by no means the product of a long relationship, but instead of a brief encounter in which the person in the image confided to me, among other things, that he had been unemployed for a long time. I was impressed by the intensity of his features that seemed almost incapable of smiling any longer. It can be clearly seen in his face that this man had lived a tough life—yet he introduced himself wearing a jacket and a clean shirt with a bright collar. He undoubtedly had a sense of pride. However, it was very important for the photo to characterize him in his surroundings, and in spite of the blurred background, the back alley of an American metropolis can be recognized. The twin attributes of brick buildings and fire escapes are enough to place him. In spite of the 400 ASA film, I could only take the photo with the light-sensitive normal lens and a relatively large aperture. It was essential to emphasize the man’s features, and the light falling from above was perfect for this job because it made his wrinkles stand out and provided some facial highlights. I had to burn in the surroundings quite a bit in the darkroom to make this unity of man and surroundings more a sociological shadow image. The Bronx is considerably larger than Manhattan and yet is barely mentioned in a tourist guide to New York—is this a sociological collective suppression? This photo also shows how strongly this individual is rooted to his surroundings by how he clearly fuses with them; you get the impression that he feels quite at home here.

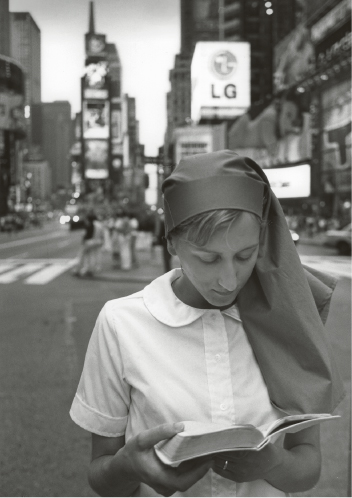

Nun in Times Square

The young sister in figure 14–2 provides a strange contrast to lively Times Square. Oblivious to the flashing advertisements, cars, and hustle and bustle of countless pedestrians in the pulsating center of New York, she stands in the middle of the street engrossed in her study of the Bible—an anachronism in the modern world. The kind of life and surroundings that have motivated this young woman to follow her religious trajectory cannot be glimpsed in this photo, but her sensitive expression does radiate a sense of calm amid the rather noisy and restless surroundings of the large city. She certainly and successfully asserts herself against her surroundings by not allowing the hustle and bustle to swallow her. Even the photo-taking process (I had requested her permission) did not diminish her concentration on the Bible. A 28 mm wide-angle lens was the right one to use here because you can recognize the background even with an almost full aperture. After all, it was important to wait for early dusk so the neon signs would be clearly recognized in the background.

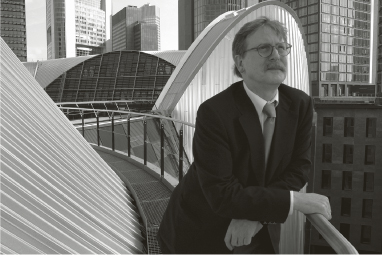

Man and Real Estate

The man in figure 14–3, the head of a Frankfurt ad agency, is at home in the modern world. Man and surroundings fuse here as well. This person, often under extreme time constraints and competitive pressure, must still be creative and innovative. With almost philosophical thoughts of the highest order, he gives modern real estate projects an intelligent image. Therefore, it made sense to fuse him photographically with one of these buildings.

It was essential to examine Frankfurt’s Junghof neighborhood very closely with the agency president before the actual shooting, so the photo session would be as brief as possible for someone whose time is so precious. During the exploratory session, the perspective that showed the roofs seemed the most interesting, and I decided that the interplay of both arches should become the formal, dominating elements of this picture. It was especially attractive for this interplay to be shown in tension with the skyscrapers of Frankfurt’s banking district towering in the background, and it was crucial to place the manager at this spot so he would be framed by the bright arch of the roof.

A fill-in flash powered down by three stops provided a soft fill-in light because he was standing in the shadow. The effect of this significantly weakened fill light is that you do not notice the flash in the picture and the face does not lose definition in the shadow. The agency president crosses his arms and looks toward the distance. His posture looks relatively relaxed, but his face expresses the energy of a powerful decision-making individual.

This photo was taken with a 28 mm lens.

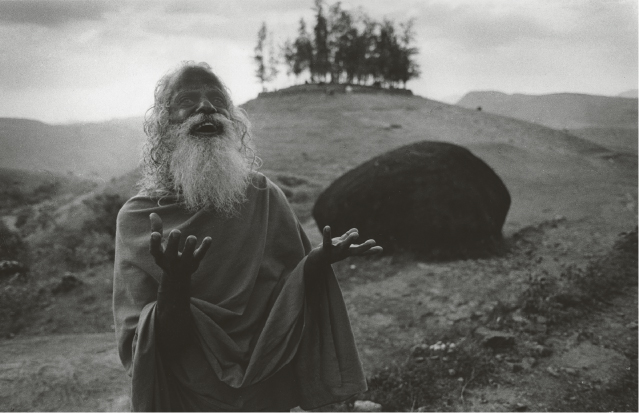

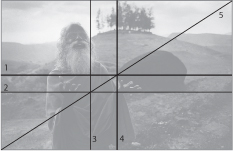

Indian Yogi

The Indian yogi (figure 14–4) comes from a very different corner of the world. During my stay in an Indian ashram while photographing a coffee-table book, I had many conversations with him. He personally guided me through the yoga exercises, and when he saw me doing them so stiffly, he frequently remarked, “After a few days, months, or years, you will do them as well as me!” For him, it was unimportant whether I would need a couple of days or years—and this is what really characterized him. As opposed to the agency president, he lived in a blissful timelessness not motivated by the pressure to succeed. This timelessness conveyed a hint of eternity, and it was important for me to place him in a relatively timeless backdrop that provided only one indication of an infinitely long time, namely a dark and eternal-looking boulder that has certainly been around for several million years. So that the boulder would not dominate the composition, it was essential to keep it in the background. The sharp focus on the yogi also emphasized the figure. Because he liked to talk and gesticulate, I had to ask him questions and observe his gestures when he answered them; I had to shoot at the right moment. Although his dark, deep-set eyes find their equivalent in the boulder, his gesture expresses something very sublime.

1 Horizontal symmetry axis

2 Lower horizontal harmonic dividing line

3 Left vertical harmonic dividing line

4 Vertical symmetry axis

5 Positive image diagonal

In the photo, taken with an analog camera using a 28 mm lens at almost full aperture, the yogi stands out well from the slightly open backdrop. I burned in the sky a little in the darkroom and slightly brightened the eyes with Photoshop’s dodging tool after scanning.

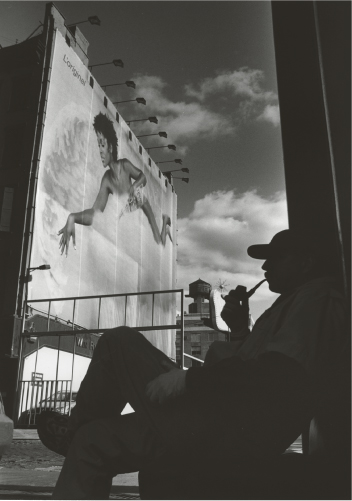

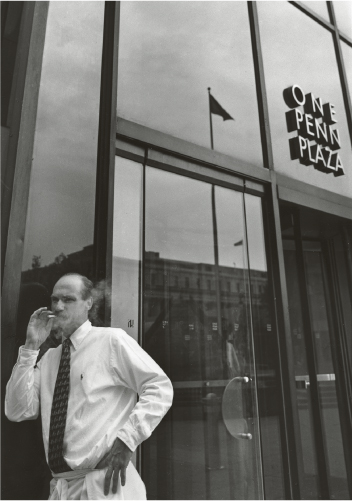

Two Smoking Breaks

The next two images both show people taking breaks—a cigarette break and a pipe break—and yet both photos express something radically different. The man at One Penn Plaza (figure 14–5) has little time for a break, while the pipe-smoker (figure 14–6) has made himself comfortable for a longer period of time by sitting on a chair. Their postures convey these differences very clearly. While the man leaning on the glass façade of a New York skyscraper seems ready to jump back to his workplace at any moment, the other one is very much at ease sitting on his small folding chair, also in the middle of New York.

Both persons have fused with their surroundings, but whereas the first man gives a rather cool impression similar to the glass reflections, the man wearing the cap and smoking his pipe looks considerably more human despite the fact that we see only his silhouette. Obviously, the juxtaposition with the floating figure on the large advertisement particularly contributes to the pictorial tension. When taking the photo, I had to make sure that hand, pipe, and face with cap would be placed before a bright section of the background so they could be easily recognized. This photo contains significantly more organic shapes, such as the clouds and the figure in the ad, whereas the other photo places the cooler, more sullen individual within an interesting design of lines, corners, and edges—another reason why this photo makes an uncomfortable impression on the viewer.

These pictures demonstrate that the ambience of the surroundings seem to define, at least partially, the personality of the person in a photo. It is, therefore, even more important to analyze the interplay of the person and his or her surroundings as thoroughly as possible in order to create a successful interaction of both of these components with all the tools of the trade and of sight.

The first photo (figure 14–5) was taken with a 28 mm lens, and the second one with a 20 mm super-wide-angle and plenty of depth of field.