Understanding Your Foods

In This Chapter

![]()

- Eating for health from all the food groups

- The best way to replace lost nutrients from certain food groups

- Consumer regulations surrounding food labels

- How to get the most information from food labels

Identifying what foods to choose and in the right amounts to create a healthy diet for yourself can be a daunting task. But with a little practice you’ll come to learn how easy eating healthier can be. When it comes to good health, eating a variety of foods every day helps ensure your body will have access to all the nutrients it needs.

In this chapter, we’ll review the vital nutrients in each of the food groups and why you need them to support a healthy body. We’ll also look at where to find additional nutrients and learn how to read the food label.

The contents of your grocery cart should reflect your plate. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans call for consuming fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat and fat-free dairy, and lean meats and seafood. Fill your plate with at least 50 percent fruits and vegetables and divide the remaining portion between lean proteins and whole grains with dairy on the side to satisfy these recommendations. Keep these guidelines in mind when you fill your cart to ensure you take home the types of foods you should be eating on a daily basis.

The Basic Food Groups

Food is divided into five basic food groups based on their similarities in nutrient content. Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and dairy make up the diverse nutrient groups. Eating a variety of foods within each food group ensures you consume all the nutrients your body needs to function and to ward off disease.

Whole Grains

Whole grains are ones that have been minimally processed, leaving the grain and its nutrient profile intact. According to the Whole Grain Council, in order to be considered a whole grain, all parts of the grain must be present. The parts consist of 100 percent of the bran, germ, and endosperm in the whole kernel.

Recommendations include eating at least half of your grains from whole grain sources. Eventually, choosing mostly whole grains rather then refined grains is a health-minded goal. Refined grains are often enriched with the vitamins they lose during processing. The information you’ll find on the nutrition label may read similar to the unrefined varieties. However, the nutrition you may receive from the added nutrients can actually be less than those that would actually come from whole grains. Many refined grains also contain added fat and sugar. Some grains may appear to be whole but have been processed. Watch for the word pearled on products such as farro and barley; it indicates the grain has been processed.

DEFINITION

A grain that has been pearled has had the outer portion polished. This process removes the bran and results in a grain no longer considered whole even though it still contains the endosperm and germ.

Ample scientific evidence exists to support the correlation between increased whole grain intake and reduction in some forms of cancer, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Whole grains are rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, including B vitamins, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and fiber.

Whole grains help you feel full longer and slow the release of insulin. Fiber from whole grains adds bulk and absorbs water, aiding in the digestion process. Vitamins in whole grains aid in energy production and the metabolism of the food you eat.

Whole grains contain amino acids in varying degrees. Some grains are considered complete proteins because they include all nine essential amino acids in adequate proportions. Some whole grains lack sufficient quantities of a few amino acids, making them incomplete. The amino acid lysine is generally lacking or in a lower proportion to the other amino acids in whole grains. By including items in your diet high in lysine (beans, legumes, and soy), you’ll make the whole grain a complete protein.

Grains that are considered complete proteins include quinoa, amaranth, millet, and buckwheat.

If you’re following a gluten-free diet, there’s no need to avoid all grains. Only grains from wheat, barley, and rye should be completely excluded. Some grains (especially oats) may be processed in plants with wheat and may contain trace levels. Check the packaging to ensure they’re considered gluten-free.

The following grains are considered gluten-free:

- Amaranth

- Buckwheat

- Corn

- Millet

- Quinoa

- Brown rice

- Sorghum

- Teff

- Wild rice

- Oats

WAKE-UP CALL

Instant oatmeal has been cut into smaller pieces and has disodium phosphate added to decrease cooking time. The addition of disodium phosphate makes this product undesirable for those watching their sodium intake. Many types of instant oatmeal also have added sugar. Instant oatmeal is still considered a whole grain, but it has a higher glycemic index than other oatmeal products due to the small particle size. Quick-cooking, old-fashioned, and steel-cut oats are all nutritionally equivalent.

Make smart choices when selecting products such as breads and cereals, as misleading labeling runs rampant in the grains aisle. You’ll find that many product labels claim “Whole Grain,” “Ancient Grain,” “Grain and Seed,” or “7 Grain.” However, you must read the item’s ingredients list to know for sure if the product is 100 percent whole grain or whole wheat. If the first ingredient is whole-wheat flour, the bread is truly made with whole wheat. If the first ingredient is enriched wheat flour, it’s not considered whole grain, but rather is made primarily or solely from processed flour. If the product claims it’s rich in whole grain or whole wheat, the terms “refined” or “processed” must not come before the word “whole.” Apply this principle to all cereal and bread products as well.

Making the transition from refined grains to whole can take some time. If you’ve always eaten white rice and pasta, slowly start converting to brown rice and pasta by mixing white and whole grain together. Finding new recipes that incorporate whole grains is helpful as well.

Adding whole grains into your dietary pattern can be simple. A serving is considered 1 ounce. This equals to about a half cup of cooked whole grains, one small slice of bread, or one cup of ready-to-eat cereal. Keep in mind that whole grains take longer to cook than refined grains. Planning ahead will make adding them to your diet easier.

If you find yourself short on time, cook whole grains ahead of time and freeze them in serving sizes for last-minute dinners. Look for precooked bags of quinoa, brown and wild rice, and mixed grains. These are easy to microwave and are shelf stable until opened. Try new varieties of grains such as bulgur, farro, quinoa, and barley as substitutes for rice and pasta. Whole grains are great incorporated into salads or on top of Greek yogurt and cottage cheese.

Protein

Protein is an integral component of muscles. Further, protein acts in every cellular function in your body. Animal protein is generally high in B vitamins, vitamin E, iron, zinc, and magnesium. Plant-based proteins are a good source of thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, phosphorous, potassium, and fiber. Some protein sources such as fish, nuts, and seeds are excellent sources of the essential fatty acids omega-3 and omega-6. Consuming adequate protein during an illness or the aging process ensures maintaining lean body mass, especially since it’s metabolically active.

Protein in your diet may come from both animal and plant sources. As previously mentioned, whole grains provide protein, whether it be complete as in peanuts, or incomplete. The most biologically available sources of protein are animal proteins such as meat, seafood, eggs, and dairy.

The biological value (BV) of protein is based on the amount of nitrogen absorbed from the protein. Eggs have 100 percent BV. Most animal protein sources are about 97 percent digestible, and plant-based proteins are between 70 and 90 percent digestible.

Many Americans eat more protein than is needed to maintain both muscle and vascular protein stores. Keep serving sizes in check to ensure that extra protein isn’t consumed and converted into fat. An amount equal in size to a deck of cards is considered a 3- to 4-ounce serving of meat and would contain approximately 7 grams of protein per ounce (21-28 grams).

With a high BV, eggs are perfect for any meal. Eggs can be poached and placed on toast, tossed over a salad, or scrambled and served alongside roasted vegetables. Keep hard-boiled eggs on hand for a midafternoon snack. Eggs are versatile and quick cooking, and can even be cooked and reheated in a microwave. Do a little online research and practice your cooking technique.

Fruits and Vegetables

Filling half your plate with fruits and vegetables will ensure you consume adequate amounts of the vitamins and minerals needed to maintain a healthy body. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports the most under-consumed nutrients are vitamins A, C, and K; folate; magnesium; potassium; and fiber. Fruits and vegetables are high in these nutrients.

Eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables has been scientifically proven to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, some cancers, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Filling up on these nutrient-packed foods will help you eat proper portions of the other food groups and aid in a balanced diet.

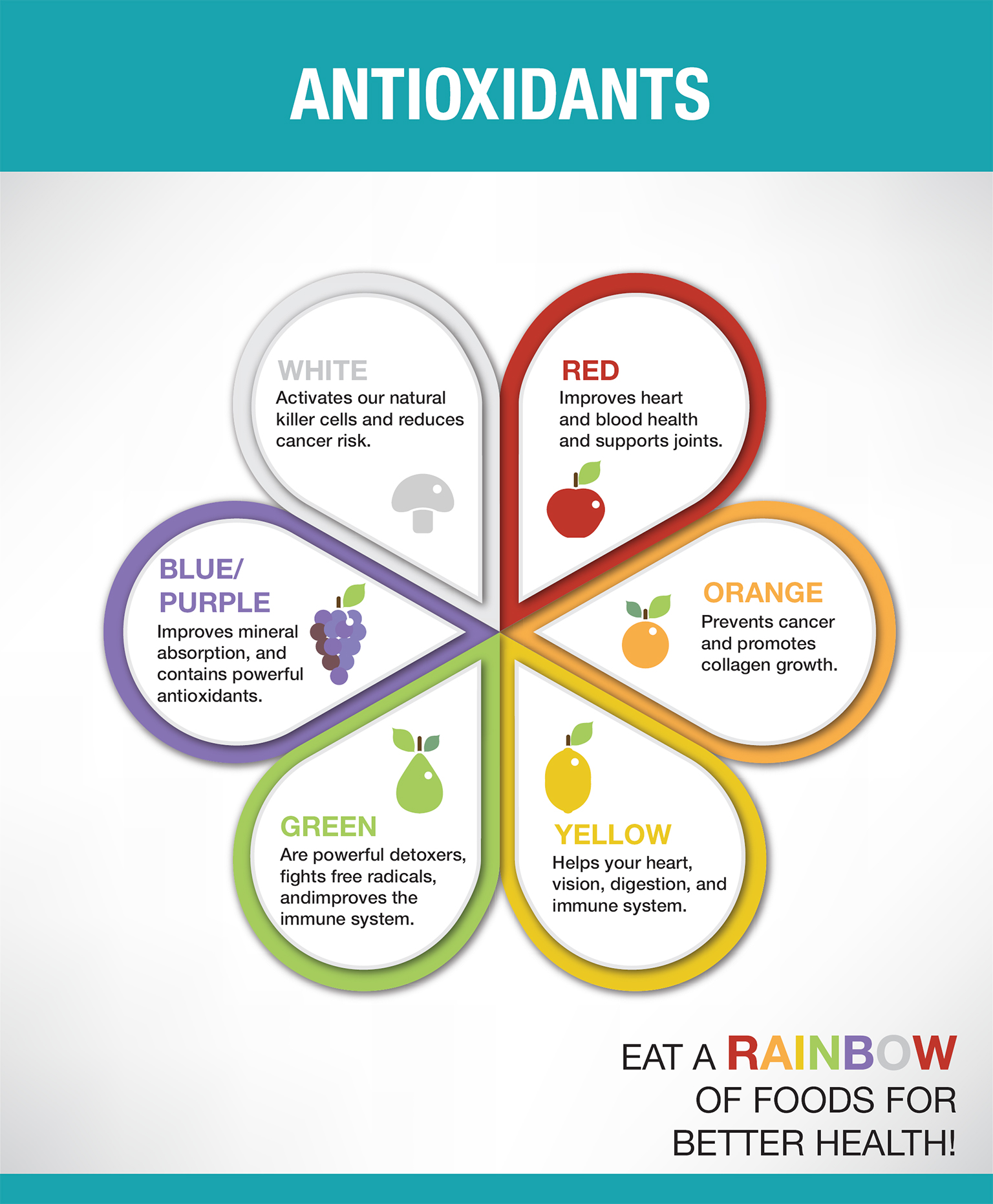

Fruits and vegetables are also packed with phytonutrients. Different colors are higher in different antioxidants and nutrients. Be sure to select a wide variety of colors when choosing what fruits and veggies to eat. The array of colors will ensure you get all the nutrients you need to keep as healthy as possible.

Fresh fruits and vegetables can be a large portion of your food budget. With some guidelines, you can always have some on hand. Always shop for produce that’s in season, which is usually advertised and less expensive. Plan to use items that spoil quicker at the beginning of the week like berries and leafy greens. Produce such as apples, bananas, oranges, carrots, and potatoes have a longer shelf life. Finally, with portable and preprepped fruits and vegetables available in the produce section, there’s no reason not to include them in your meals.

Canned fruits and vegetables also are a great backup for when you run out of fresh ones or their price are high. Look for varieties with reduced sodium and rinse them well before heating. When you select canned fruits, be sure they are packed in their own juice without any added sugar. Once the cans are open, be sure to store the contents in a refrigerator-safe container. Leaving them in the can may alter the taste.

Frozen fruits and vegetables picked at their peak of freshness are a wonderful solution. Items can be kept in your freezer for months and pulled out when you’ve eaten up your fresh purchases. Frozen fruits and vegetables are also great in smoothies and stir-fries.

WAKE-UP CALL

Food cans and plastic bottles are lined with an epoxy containing the chemical BHA. The FDA believes BHA is safe, but they’re continously researching to determine if it’s leaching into the contents. They’re also looking at what health detriments it may be causing. If you’re concerned about the possible effects of BHA, look for containers that are labeled BHA-free. Keeping bottles and cans out of the heat will also reduce the likelihood of BHA contaminating the food.

Dairy

Dairy products are an excellent source of calcium, vitamin D, and potassium. Some dairy products, such as kefir and Greek yogurt, contain probiotics. Generally, low-fat and nonfat milk and yogurt are recommended due to the lower saturated fat content. If you’re choosing nondairy alternatives such as almond or soy, be sure you choose unsweetened varieties that are fortified with calcium and vitamin D. Dairy milk is a great source of protein, but not all alternatives contain protein. Be sure to read the nutrition facts label.

Cheese, like other dairy products, is a good source of protein. Use cheese in moderation and opt for strong-flavored cheeses like feta, blue, or Parmesan to add to salads. If you’re a cheese lover, splurge on a different kind from the gourmet cheese section in your store once a month. The flavors are unsurpassable, and you can eat a slice or two a day as a snack along with apples, grapes, or a handful of nuts.

Processed cheese is a blend of cheeses with the addition of disodium phosphate. Often processed cheese will not contain enough true cheese to be labeled as cheese and may be referred to as a cheese food. They also have additional added oils and may be much higher in calories.

Greek yogurt and cottage cheese are also a great source of protein and supply needed calcium. Look for low-fat or nonfat options without added sugar. Cottage cheese can be high in sodium, so be sure to compare the brands when making your selections. Add fruits, nuts, and ground flaxseed to your yogurt. Use cottage cheese to add protein to your salads or to top a baked potato. Nonfat plain Greek yogurt is a great alternative to sour cream and provides more protein and less fat.

Healthy Fats

Healthy fats can help brain function, slow down cognitive decline, and help maintain optimal cholesterol levels. Choose fat sources that are liquid at room temperature. Use monounsaturated fats such as olive oil in place of butter. Eat unsalted nuts and seeds high in omega-3s.

Fish is an excellent source of omega-3 fatty acids. Eat fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, sardines, anchovies, and rainbow trout in 4-ounce portion sizes, two to four times a week. The University of Michigan Integrative Health department recommends a ratio of two to four times as much omega-3 in your diet as omega-6.

What If I Eliminate Food Groups?

Oftentimes, eliminating foods may be necessary due to allergies or religious or social beliefs. Eliminating specific foods will not generally cause problems in maintaining a balanced diet. However, when entire food groups are eliminated, the nutrients readily available in that group must be added to the diet in other ways. Being aware of your reasons for eliminating entire groups and making efforts to replace those lost ingredients will help alleviate any nutritional deficiencies.

Dairy Alternatives

Many individuals who are lactose intolerant can’t tolerate any dairy foods. For them, consumption of lactose causes cramping, gas, and diarrhea due to their body producing very small amounts of the enzyme lactase needed to break down lactose. Lactose-intolerant people, however, may be able to consume yogurt in small amounts due to the yogurt’s probiotics, which have already broken down some of the lactose. Additionally, the probiotics will aid in supporting a healthy gut environment, which will help with digestion. Hard and aged cheeses, such as Swiss and cheddar, have low lactose levels and may also be tolerated. If you’ve eliminated dairy altogether due to lactose intolerance, try slowly adding hard cheeses, yogurt, and dairy back into your diet a bite at a time to help build up a tolerance.

NOTABLE INSIGHT

Lactose intolerance is a condition that often affects individuals as they age. The National Library of Medicine estimates 30 million Americans will have some degree of lactose intolerance by the age of 20. Trauma to the GI tract may cause transitory lactose intolerance, which often subsides as the gut returns to normal functioning. In rare instances, babies may be born with a genetic defect that makes it impossible for their body to produce the lactase enzyme.

Products that contain the lactase enzyme may also be an option for those with lactose intolerance. These lactase-added enzymes also break down the lactose disaccharide into two monosaccharides for ease of digestion. Lactaid milk has a similar nutrition profile to fat-free milk. Yogurt, cottage cheese, and other dairy products are available in Lactaid versions.

Milk alternatives are plentiful if you choose to not drink dairy milk. Soy, almond, coconut, and rice milk are all readily available. Since these options aren’t animal-based, their nutrient profile will differ. Many alternatives fortify their products with calcium, protein, and vitamin D to make them more comparable to dairy milk. Be sure the option you choose doesn’t have added sugar.

Gluten-Free Alternatives

Individuals with celiac disease must avoid foods containing gluten due to the inability to digest gliadin, a protein found in gluten. Other individuals have medically diagnosed gluten sensitivity without having the antibody for celiac disease. These individuals may experience symptoms similar to celiac disease without the intestinal damage. Other individuals follow a gluten-free diet due to the “health halo” gluten-free products currently have.

Oftentimes individuals “feel better” when they stop consuming gluten, because they’re giving up refined carbohydrates along with the added sugar and fat that accompanies so many products containing gluten. Keep in mind that gluten grains generally are not the culprit for those without medically diagnosed sensitivity or allergies. Switching to only whole-grain products without added sugar and fat may have the same benefits.

Due to trends and consumer demand for gluten-free products, following a gluten–free diet is not as obtrusive as it once was. For example, pastas made with quinoa or brown rice are readily available. The wide availability of less-common grains like quinoa and amaranth has also given those avoiding gluten-containing grains more options.

There are gluten-free flour alternatives for the home baker. The flours use a combination of rice flour, cornstarch, milk powder, tapioca flour, potato starch, and xanthan gum.

DEFINITION

Xanthan gum is an ingredient often used in gluten-free foods. It’s a polysaccharide made by bacteria. Xanthan gum is used as a food additive and acts as a stabilizer and thickener. In 1963, it was approved for food use after undergoing extensive safety testing. It’s on the FDA’s list of approved food additives.

Reading food packages has become simpler due to the FDA’s definition of gluten-free. According to the FDA, if products are labeled gluten-free, they must either inherently be gluten-free or not contain or be made from a gluten grain. All products labeled as gluten-free must contain less than 20 parts per million of gluten. This labeling is voluntary and food producers aren’t required to label their foods as gluten-free.

Food Combining

Foods are generally eaten in combination with other foods at one sitting or at some point in the same day. Some food groups need a complementary food in order for it to be considered “whole.” As discussed in Chapter 7, most plant-based proteins are not complete proteins and lack sufficient amounts of the amino acid lysine. To make them a complete protein, you should eat a second protein high in the amino acids they lack. For example, beans are low in the amino acid methionine and rice is low in lysine. If eaten together or in the same day, the shortcomings of one food make up for the other.

Traditionally, two complementary foods are often served together. Beans and rice, hummus and a pita, and a peanut butter sandwich are all examples of successful pairings to make up what is known as complete proteins.

The Food Label

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for ensuring foods sold in the United States are safe for consumption. The two main laws that outline how foods should be labeled are the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (FP&L Act). The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) then amended the FD&C Act. These regulations lay out standards and claims allowed on labels. All labeling must be done with the intention to not deceive the customer.

The nutrition facts label, as we know it today, was mandated in 1993. Only small changes have been made over the past two decades, and it’s in need of reform to reflect how consumers today use the information provided. Proposed changes include new actual serving sizes, added sugar, amounts of vitamin D and potassium, and removing “calories from fat” information due to the lack of usefulness. The label will also get a new look with calories highlighted, shifting %DV to the left, and additional reconfiguration for consumer ease.

The nutrition facts panel or food label is designed to help you understand how a food fits into your diet by providing information on serving size, calories, fats, and key vitamins and minerals. Courtesy of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The NLEA was added to the regulations to require that food be labeled with basic nutrition information and health messages. Packaging must also include the name and address of the distributor, producer, or manufacturer.

According to the FDA, the label must include what the product is (name) and how much of the product is in the package (amount). Size and font type as well as location of required information is specified according to the package type. Not all information will be in the exact same location on every food package.

Each food product must contain a list of ingredients. Ingredients should be listed in order by weight, meaning the ingredient in the largest proportion in the product is the first listed. The ingredients in the smallest proportion are listed last. Ingredients are noted by their common name known by consumer, not the scientific name. If an approved chemical ingredient is used in the product, the common name and use should both be listed (e.g., “ascorbic acid to promote color retention”). Allergen terms must also be included.

NOTABLE INSIGHT

The following must always be labeled on foods:

- Alcohol

- Aspartame for those with phenylketonuria (PKU)

- Sulfites

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG)

One of the not-so-healthy things you need to be cognizant of is that trans fat listed as 0 grams may actually contain up to 0.5 grams by law due to rounding regulations. Read the ingredients list and if hydrogenated oil or partially hydrogenated oil is listed, then the product contains some trans fats.

The Serving Size

The serving size listed on the nutrition facts label is often very different from what you may consider an actual serving. Don’t assume an entire package or container of an item is one serving. The serving size is noted at the top of the nutrition facts label. The size should be listed in units the consumer can relate to, such as cup or tablespoon. The common measurement is followed by a metric measurement. In addition to serving size, you should note how many servings are included in the package. This may give you a better idea of how much of the product you can eat at one sitting.

New guidelines have been proposed for changes in serving sizes. In the last two decades since the creation of the nutrition facts label, serving sizes have grown. The FDA recognizes this and is moving toward mandating that serving sizes be more reflective of the quantity consumed at one sitting. A small bag of chips may currently be four servings. With the new proposed regulation, the entire bag would become one serving. Nutrition facts labels may indicate what the nutrition facts are for the entire bag along with a smaller portion, such as 1 cup.

What Is % Daily Value?

Based on a 2,000-calorie diet, the % daily value (%DV) is the recommendation for key nutrients. Using the percentages along the right-hand side of the nutrition facts label, you can determine if the product is a good source of the key nutrients. For items you would want to limit, such as saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium, having a %DV of 5% or less is ideal. For those you would want more of, such as fiber, vitamins, and minerals, 20% or more is ideal. “Good Source” foods must provide 10 to 19% of the daily value of whatever they are a good source.

You can use the %DV to compare similar products for a quick reference as to which product is higher in calcium or fiber. Be sure you’re comparing equal serving sizes. Instead of looking for words that may be misleading such as “light” or “low-fat,” read the %DV and see for yourself.

Not all nutrients have a %DV. Protein-containing products must contain one if the product makes a label claim about the amount of protein such as being “high-protein.” No daily value has been set as acceptable intake for sugar. The amount of sugar included on the nutrition facts label includes sugars occurring naturally as well as added sugar. However, there is a push for labels to differentiate between the two types of sugar.

Packaging Claims

There are three types of claims allowed by the government that manufacturers can make on their labels: nutrient claims, health claims, and structure/function claims. Each type has specific requirements associated with its use. Let’s take a look at each type of the legal claims that can be made on products.

Nutrient Claims

Nutrient claims relate to actual nutrient or implied levels. Examples of claims include “low fat,” “reduced calorie,” or “100 calories.” Claims are usually only for nutrients that have daily value % daily value associated with them. The FDA has specific nutrient claims allowed on packaging. Any claim not on the list is not allowed.

Relative nutrient claims compare the amount in the product to a reference food. These statements include terms such as “light,” “reduced,” “added,” “more,” or “less.” Other nutrient claims such as “high,” “lean,” and “antioxidant” have specific definitions tied to them.

If a nutrient claim is made on a product, generally a disclosure must be included if the product contains more than 13 grams total fat, 4 grams saturated fat, 60 milligrams cholesterol, or 480 milligrams sodium, for example. These nutrient levels are considered above the Reference Amount Customarily Consumed (RACC). Allowed nutrient levels for meals are higher. The disclosure statement helps eliminate any possibility the claim will be misleading to the consumer.

Health claims may be printed on food packages, are strictly regulated, and must be approved by the FDA before use. A health claim is when the benefit of a product is linked to a disease or condition. The claim may be explicitly stated (“Diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol that include 25 grams of soy protein a day may reduce the risk of heart disease”) or be implied (such as the heart symbol). Claims may only apply to prevention, not treatment or cure of diseases.

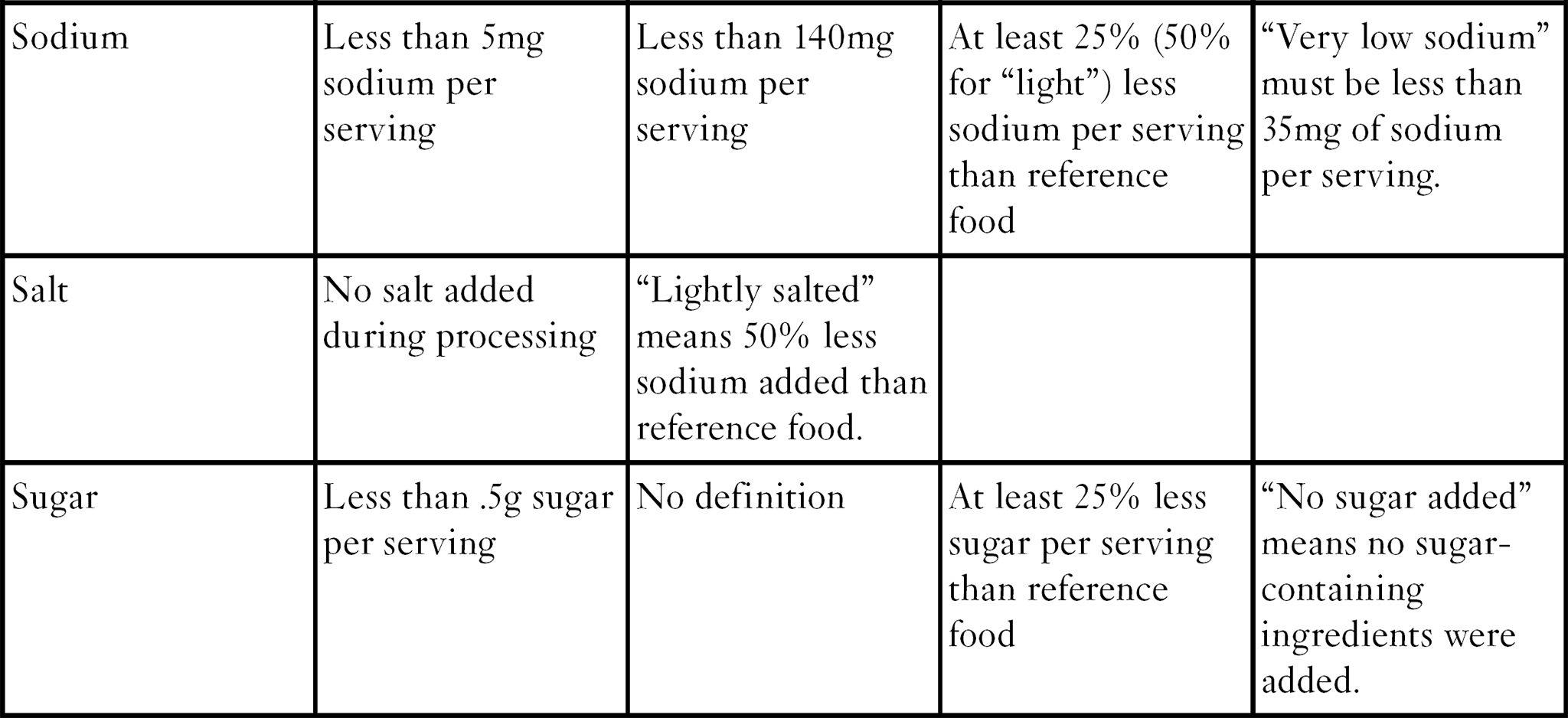

The following table provides a description of what the words found on a label mean.

Adapted from FDA Guidance for Industry: Food Labeling Guide.

Health Claims

Another category of claims food companies can make about their products are health claims. The FDA strictly regulates these particular types of claims. Health claims are made when a food or ingredient of the food has a relationship with a disease or health condition. These claims have science backing them up and have also been reviewed by the FDA. Health claims have two parts to them. The first is the food or food substance, and the second is the disease or health condition.

NOTABLE INSIGHT

Oftentimes food companies will petition the FDA for new health claims. The FDA will review the scientific evidence to determine if enough evidence is available to draw health conclusions. If the FDA finds enough evidence to support the health claim, it’s approved and will subsequently be added to the list. If the evidence is weak or lacking, the FDA will deny the petition.

The following is a list of the approved health claims. Only these links between food or food substances and listed disease or health condition may be made.

- Calcium and a reduced risk of osteoporosis

- Calcium and vitamin D and a reduced risk of osteoporosis

- Dietary fat and a reduced risk of cancer

- Diets low in sodium and a reduced risk of hypertension

- Diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease

- Fiber-containing grain products, grains, fruits, and vegetables and a reduced risk of cancer

- Fruits, vegetables, and grain products that contain fiber, particularly soluble fiber, and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease

- Fruits and vegetables and a reduced risk of cancer

- Folate and a reduced risk of neural tube defects

- Dietary noncarcinogenic carbohydrates and sweeteners does not promote dental caries

- Soluble fiber from certain foods and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease

- Soy protein and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease

- Plant sterol/sterol esters and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease

- Whole grain foods and a reduced risk of heart disease and certain cancers

- Whole gain foods with moderate fat content and a reduced risk of heart disease

- Potassium and a reduced risk of high blood pressure and stroke

- Fluorinated water and a reduced risk of dental caries

- Diets low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and trans fat may reduce the risk of heart disease

- Substitution of saturated fat in the diet with unsaturated fatty acids may reduce the risk of heart disease

Structure and Function Claims

The structure and function claims category made on food labels describes how a nutrient or food will affect the healthy structure or ability of the body to function. These claims don’t need to be approved by the FDA and are not preapproved. However, the product must also state the food will not “diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” According to the FDA, structure/function claims are phrases such as “calcium builds strong bones” or “fiber maintains bowel regularity.”

- Eating a balanced diet consists of eating proper portions and combinations of foods from all of the five basic food groups.

- If you eliminate entire food groups, do your homework to determine how you can make up for missing nutrients.

- Food labels are intended to give you the information necessary to make smart and healthy choices.

- Learning how to read the nutrition facts label will help you compare foods, moderate your portions, and estimate your daily intake.