It’s hard to believe that the World Wide Web is almost 30 years old. While technically launched in 1991 by Tim Berners-Lee, most people didn’t really know about it until the mid-1990s. The Web as we know it today really took off in the late 1990s with the “dot-com” boom and subsequent bust. We’ve come a long way since the early days of Mosaic and Netscape Navigator (the first popular web browsers). Web pages have gone from simple blocks of text and hyperlinks to amazingly powerful and complex websites that can do just about anything. Many of the tasks that were relegated to heavyweight software applications like Photoshop and Microsoft Office are now moving into “the cloud.” With high-speed Internet connections and powerful new web technologies, there’s so much you can now do within the confines of your web browser. In fact, Google has a whole operating system called Chrome OS that is essentially a web browser that acts as a full-fledged desktop operating system. (This OS is the basis for the popular and inexpensive Chromebook laptops.)

Much of what we do today on our computers is surfing the Web. (I must admit I never understood that phrase…wouldn’t you be crawling a web? Or even getting stuck in a web? I guess it makes as much sense as “channel surfing,” which is probably where we got the term.) So, in this chapter we’re going to learn about how to surf safely.

The way we access the Internet directly is usually with a web browser. Therefore, we need to find a good one—and by “good” I mean safe, not just full of whiz-bang features. Microsoft and Apple each have their own browsers that come with their operating systems: Edge on Windows and Safari on Mac OS. And because most people take the path of least resistance, these default web browsers tend to be popular on their respective platforms.1 However, there are better choices out there, and in this chapter I will help you choose the one that’s best for you.

Because web browsers have become the portal to the Internet, the bad guys have focused a lot of time and attention on finding ways to track, scam, and even infect you via this magical gateway. The functionality of a web browser can be extended in many ways, including plugins, extensions, and add-ons. I will help you figure out which of these are good, which are bad, and which are just plain ugly.

Before we get into those specifics, let’s dig a little deeper into how security works on the Web. This is going to sound rather technical, but it’s important to understand the basics at a high level. Don’t worry too much about the acronyms in this chapter—you don’t need to memorize them. But I want to get the terms out there in case you’ve seen them before or run into them in the future. The real key thing to take away here is the general “web of trust” concept that forms the basis for our current Internet security scheme.

Recall that all your computer communications (in both directions) are chopped up into small packets and shipped out over a massive web of interconnected computers. The packets will take many hops before they reach their destination, and each packet could take a slightly different path—it doesn’t really matter, as long as they all reach their destination. Previously in this book, we discussed the basic issues that we need to address when trying to communicate securely over the Internet. First, we need to somehow ensure that the person or website we’re communicating with is actually who they say they are. Second, we would like our communications to be completely private—that is, we don’t want anyone between us and our intended recipient to be able to read what we’re saying or what data we’re exchanging. Finally, we would also like to know that the messages haven’t been tampered with along the way (you don’t have to be able to read something in order to alter it).

The way we secure Internet communications and authenticate third parties is using a technology called Transport Layer Security (TLS).2 TLS is used all over the place today to secure all sorts of communication, including digital phone calls, file transfers with cloud storage providers, and, of course, web surfing. When TLS is added to regular web communications via a browser, we move from “HTTP” to “HTTPS”—the added S stands for “secure.” When you are connected to a website via HTTPS, you should see a little lock icon to the left of the web address that indicates that the connection is secure.3 Most of this happens automatically behind the scenes. Your web browser and the server at the far end do some quick negotiation, and when both sides are capable of using TLS, they establish a secure connection.

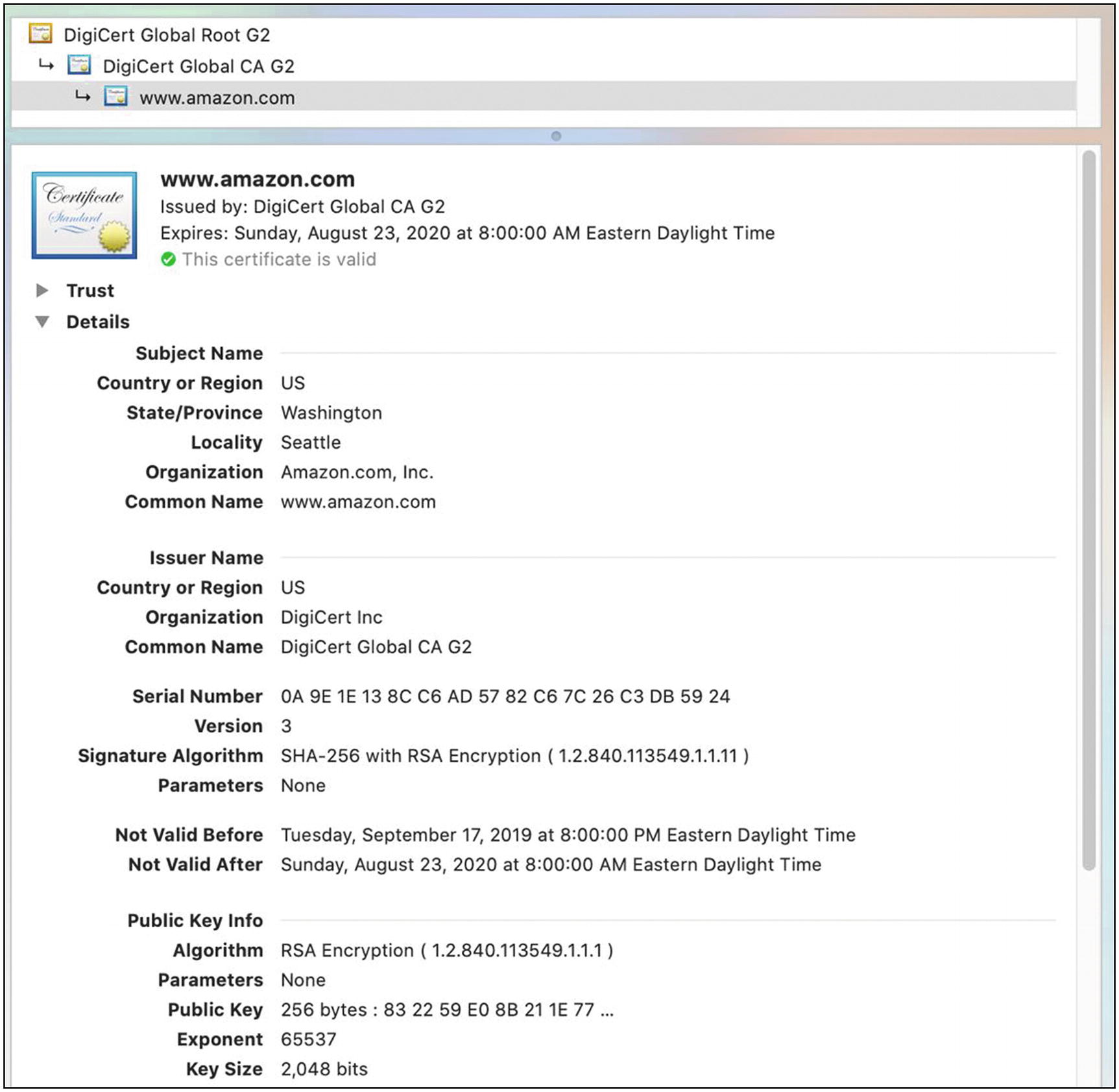

Sample certificate

Once the CA issues a cert to the owner of the website, the website provides the cert as proof of identity when establishing a secure connection. This is like showing your driver’s license when buying booze to prove that you are who you say you are and that you’re old enough to buy alcoholic beverages.

But wait…driver’s licenses can be faked. What about certificates? Well, I’ve got good news, and I’ve got bad news. The good news is that because certificates use solid cryptographic methods for creation, CA-backed certs can’t really be forged. While it’s possible to create “self-signed” certificates, no one is going to trust it for anything important. Web browsers have a built-in list of certificate authorities that they trust, and Joe Blow is not going to be on that list—just like liquor shops would only accept driver’s licenses from the 50 US states and they probably have a folder that shows what each state’s license should look like. Creating a self-signed certificate is like printing up a homemade ID card on your printer and laminating it. Sure, it looks nice, but it’s not going to get you into a bar. Self-signed certificates can be used to properly encrypt communications; you just can’t be sure who it is you’re talking to.

So, that’s the good news. The bad news is that there are other ways to get a certificate that are arguably worse. Creating a trustworthy certificate is a crucial task, so you’d think we would limit this job to a select few organizations that we can all agree to trust. In practice, there are hundreds of certificate authorities in the world, including the Hong Kong Post Office (I’m not kidding). Any one of these CAs can issue a completely authentic certificate that contains nothing but lies, if they choose to. We trust them not to do this, but if they “go rogue” or if they get hacked, it’s possible for bad guys to get perfectly legitimate certificates that will allow them to impersonate Google or Yahoo or whoever they want. It would be like getting your “fake ID” directly from the Department of Motor Vehicles…it would be fake only in the sense that it contained wrong information, but it’s a perfectly valid driver’s license that would pass any examination.

As bad as this sounds, in practice this is not easy to do. You’re not worried about average teenager hackers in this situation; you’re worried about highly skilled and well-funded attackers, probably backed by a government or a big corporation. The target in this case would mostly be information (espionage). Also, there are other safeguards in place that mitigate the risk of being duped by one of these bad certs. For one thing, even if the bad guys get their hands on one of these mendacious certs, they still have to somehow get between you and your target server. This is a “man-in-the-middle” attack, which we discussed earlier—they insert themselves in the communication channel and pretend to be the other side to each end. That is, you establish communications with them, and then they turn around and establish communications with Amazon.com, let’s say. To you, they appear to be Amazon.com; to Amazon.com, they appear to be you. To do this, they need to somehow redirect you to the false website instead of the real one. When you type amazon.com into your web browser, it uses the Domain Name Service (DNS) to figure out where your request really needs to go on the Internet—that is, the IP address of Amazon’s web server. Unless you can somehow also intercept that DNS lookup and provide a hacked reply, then the user will still be connected to the real Amazon website. Also, there are new technologies coming online that will make this even more difficult in the near future (like Google’s Certificate Transparency4 project). So, while there are definite problems with the current CA-based system, it still works very well for the vast majority of web surfers, and other safeguards are being put in place to make it much harder to thwart or subvert.

So, if we can assume that the certificate system works (which is, as we’ve said, a significant “if”), then we can assume that when we establish an HTTPS connection to another website that (a) we can believe they are who they say they are and (b) no one else can eavesdrop on our communications.

There’s one last—but crucial—point here. When you see that lock symbol on your web browser, that means your traffic is encrypted and that the certificate used by the website is valid. That’s all. It doesn’t mean you can trust the owner of the website. You can now get free entry-level certificates thanks to an effort by a large consortium of companies called Let’s Encrypt. That’s great—it makes it much easier for mom-and-pop companies to offer secure communications to their website. But the bad guys can also use this free service to obtain a valid certificate for a malicious website. So, the lock icon doesn’t mean the website you’re on is trustworthy; it only means that no one else can spy on your communications with them.

Again, don’t worry about remembering all the technical details. All you really need to remember here is that HTTPS connections are secure. Most websites are moving to HTTPS for all communications, which is a good thing, because everything we do on the Internet should be safe from prying eyes, even simple stuff. In the next section, we’ll take a look at just how pervasive web tracking has become.

Tracking Tech

While secure communications are vitally important, we have to also address the elephant in the room: web tracking. The amount of information you divulge every time you use a web browser is absolutely staggering: what websites you visit, how long you stay on a given website, how you got to that website (i.e., which site you just came from), whether you bought something on a given website, what ads you saw, what links you clicked, and even how much you spent while there. There has been a lot of debate on the value of this “metadata,” but the proof is in the pudding, as they say. These companies wouldn’t be bending over backward to get this info if it wasn’t making them money. And just in case you think it’s only retailers that are trying to find the right way to hook you into buying that spiffy new TV or anti-aging cream, you should also know that the politicians are using this data, too. Maybe they want to find sympathetic potential voters and even to identify voters who might be convinced to switch sides. But they would be just as happy to convince or trick people likely to vote for their opponents to stay at home on election day. The recent scandal involving Facebook and Cambridge Analytica is a shining example. And of course this treasure trove of personal data is also potentially available to law enforcement and intelligence agencies, as well.

This data is often used to specifically tailor a website just for you—and not in a good way. For example, if the retailer happens to know that you’re wealthy or that you’re a heavy online shopper, they can actually make sure to show you the more expensive products first—in fact, they may even raise the prices5—if not based on your information specifically, perhaps based on whether you appear to be from a wealthy area.

The Webs We Weave

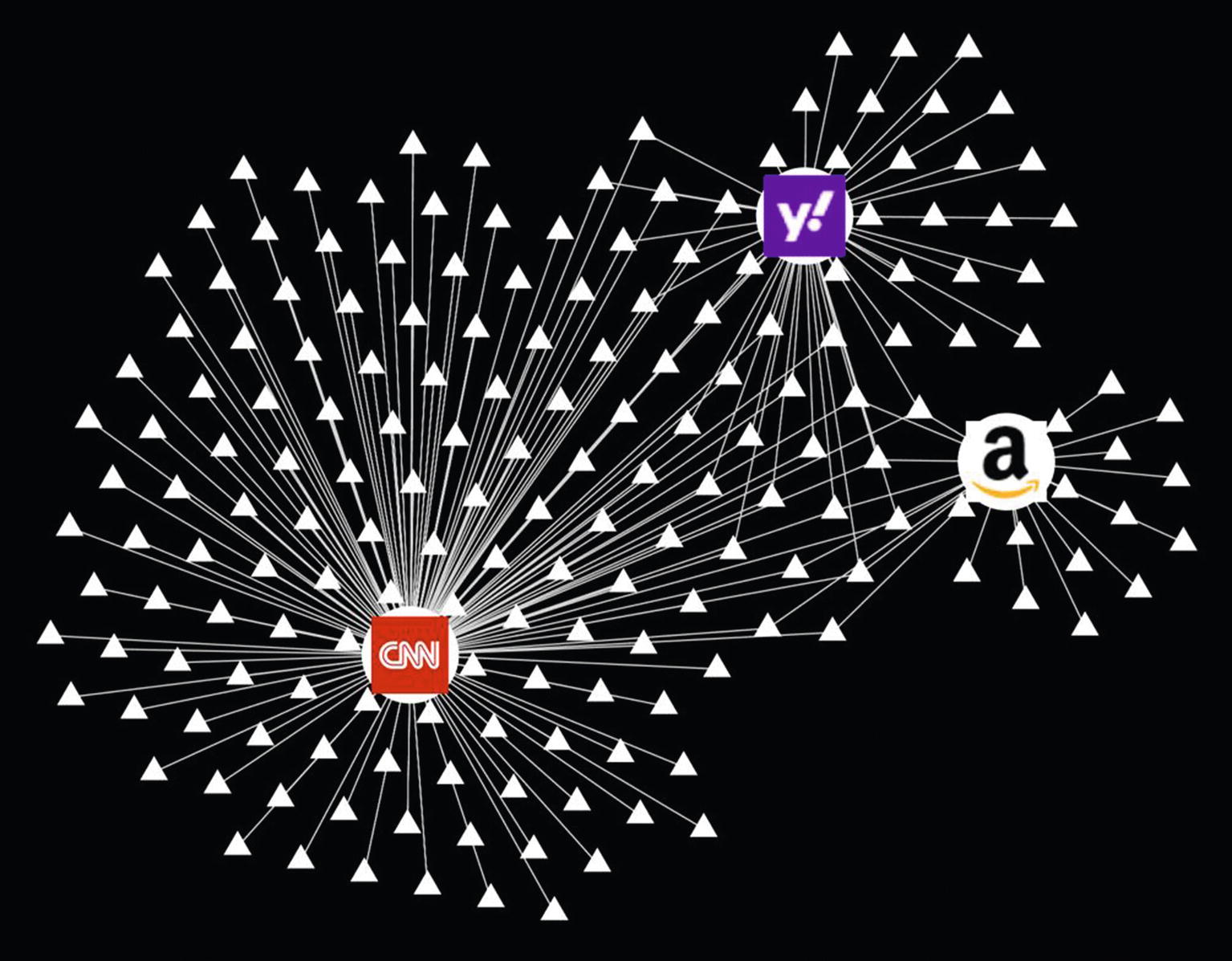

Most people just don’t realize how wide and vast this tracking network really is. The best way I know to explain the pervasiveness of web tracking to you is to use a nifty little web tool called Lightbeam .6 When you go to a website, the content you see is often provided by multiple different companies. Think of a web page as more of a patchwork quilt, with each panel coming from many sources. In addition to the first-party site (the website you actually intended to visit), there are often many other third-party websites that provide ads and other images—and also track what you’re doing. To see these third-party relationships, Lightbeam draws a graph that shows you all the third-party sites that are associated with the first-party site you visited. (I know, all this “party” stuff sounds like legalese. It sorta makes your brain want to tune it out. But bear with me here.)

Wikipedia graph

In Figure 7-2, you’ll see the first-party site as a circle—in this case, the one with a W in it, which is wikipedia.org. The little white triangle next to that is a third-party website that is associated with the site we visited. However, in this case, the third-party site is just wikimedia.org, which is directly associated with Wikipedia (i.e., it’s not a third-party advertising or tracking site). It’s not uncommon for the third-party sites to just be extensions of the first-party site. And it’s also not uncommon for the third-party sites to be perfectly normal other websites that provide things like web tools, images, and other harmless content. However, many of them are marketing firms and other “Big Data” companies whose sole purpose is to build a portfolio on you.

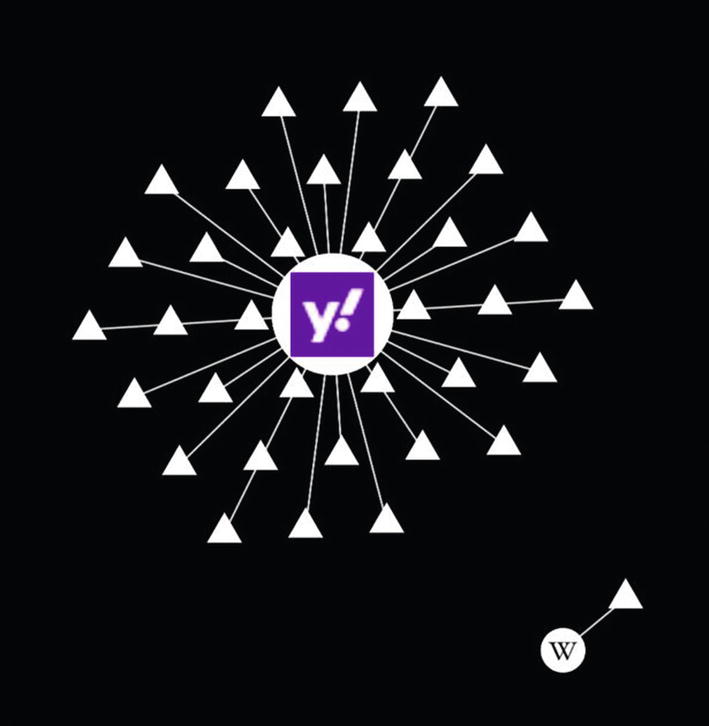

Wikipedia + Yahoo graph

Our little graph (Figure 7-3) has now grown substantially. While Yahoo.com was our primary target (the big white circle at the left with the “Y” in it), we can see that we’ve also triggered a few dozen other sites, almost all of them tracking sites. Note that there is no intersection here between the two main websites—no common third parties. Wikipedia—since it doesn’t track you—is actually pretty boring in this regard, so from here on, we’ll just cut them out of our picture.

Yahoo + Amazon graph

You can see in Figure 7-4 that loading Amazon’s website also caused you to communicate with several other third-party websites. Now we can see the overlapping third-party sites. Those are all tracking sites. And they now know that you went to Yahoo and then to Amazon, and they quite likely know a lot about what you did there. Starting to get the idea?

Yahoo + Amazon + CNN graph

The graph in Figure 7-5 is so crowded now that you can’t really even read it. It’s hard to tell, but there are 183 third-party websites there. You’ve visited just four websites so far. The triangles that have multiple connections are the tracking sites.

So, just exactly how is it that they track you? The details would make your eyes glaze over. It’s very technical, and the techniques are legion and myriad. But essentially it boils down to somehow marking you in a way that can later be recognized if they (or someone they know) see you again. These markers come in many forms. One of the most popular tracking devices is called a cookie. A cookie is a small bit of data that websites give to your computer, asking your browser to save it off and then repeat it back to them later when they ask for it. This is sort of like a medical chart—the information is kept on you, and when you interact with another party, they look at it to refresh their memories of you. These cookies were originally used by the first-party website to help keep track of your login, your personal preferences, your shopping cart contents, and so on. However, third parties have used them to mark people as they move around to different websites, tracking all sorts of stuff about you. That’s the key point here…first-party cookies are between you and the site you intended to visit, which tends to be mutually beneficial; third-party cookies are things you generally didn’t ask for and may not even be aware of, and it’s almost completely for the benefit of the third party.

Let’s try an analogy to explain how this works. Let’s assume that your local mall wants to gather information on the people who shop there, and all the merchants agree to participate in the program. It’s time for you to go Christmas shopping, so you park your car and walk in via the Macy’s door. As you walk through the door, a silent little blowgun shoots a sticky dart that attaches to your back. This dart contains a little homing beacon that puts out a unique identifier, specific to you. They don’t know who you are (yet), but they want to be able to distinguish you from all the other people wandering the mall. This ID is logged in a special computer system, along with a little note: “Customer 4372 entered mall via Macy’s East door on first floor.” This entry in the log automatically notes the time and date, as well. You walk through Macy’s and into the mall proper. As you do, you walk by another sensor that detects your tag: “Customer 4372 left Macy’s without buying anything.” Since the time of entry and time of departure were so close, they could probably also conclude that you didn’t even look at anything.

Now you walk into a jewelry store. You look around, find the perfect gift—a diamond tennis bracelet—and go to the register to buy it. Your entry to the store was of course logged, but now you’ve also made a purchase. They now know quite a bit more about you. If the store is trying to be nice, they may only log that you are a white male in his mid-50s who lives nearby (based on your credit card billing address) and that you bought an expensive piece of jewelry. From this, other retailers in the mall (who can see all of this information) may well assume that you are married and have an above-average income level.

You leave the jewelry store and head down to Victoria’s Secret, where you make a very different purchase on a rarely used credit card. Marketing data analysis may suggest that you have not just a wife but also a mistress. You now walk into an electronics store. The store personnel can see from your records that you’re in a buying mood today and you have plenty to spend, so they ignore other customers who show less promise and focus on you. They steer you to higher-end equipment, and given that you probably have a wife, they test your interest in kitchen appliances and push hard for you to get a store credit card.

This is all just from a single trip to the mall. Think about all the other places you’ve been and purchases you’ve made—what could they tell about you? How detailed would your profile be? And would you want that profile to be shared with every store you walk into?

The key here is that all the stores have contracted with the same tracking company. They have a common set of sensors that are all networked together, creating a central place to log your activity. While you might think it’s entirely reasonable for a given store to keep information on previous buying and shopping activity, how do you feel knowing that information is being shared with many other retailers (and credit bureaus, potential employers, insurance companies, etc.)? It may be that this tracking company hordes the juiciest bits of information and gives only partial information to each store owner (depending on what level of service they’ve paid for). But it’s important to realize that even with the best of intentions, the fact of the matter is that that information exists somewhere—and therefore it can be stolen, abused, or even compelled by the government.

Enter the Panopticon

But we’re just getting started! There are several other tracking mechanisms, as well. People have gotten wise to the third-party cookie tracking method and have learned how to block them, so marketing companies have come up with other ways to track you—ways that can be difficult to avoid. If they can convince (or trick you) into installing a browser extension, they can potentially access all of your web surfing data. Even those social media buttons such as Facebook’s Like, Pinterest’s Pin It, and Twitter’s Tweet can be used to track you—even if you don’t click them! Sometimes they use tiny little one-pixel images with unique names…when your browser loads that image, they know you’ve been there. Sometimes they use invisible web form fields. The list goes on and on, and the exact techniques change all the time.

Some really clever folks have figured out ways to “fingerprint” your web browser. To help websites present themselves optimally, your web browser gives up all sorts of general information about your computer and web browser configuration: what plugins you have installed (even if they’re disabled), all the fonts you have on your computer, computer screen dimensions, what type of operating system you’re running, and what type of browser you have. The idea behind browser fingerprinting is that few people will have the exact same combination of these items.

Unlike regular cookies and other forms of tracking, there is no way to know that browser fingerprinting is happening to you, and it’s very hard to prevent. It’s just not easy to disguise yourself as you traverse the Internet. In this case, your best defense would be to look like everyone else—blend into the crowd. Unfortunately, many of the measures you might take to increase your online security and protect your privacy also tend to make you stand out because so few of us take the time to install these tools. Finally, this is just one technique—if you combine this technique with others (even just looking at your IP address), it becomes extremely difficult to hide your tracks.

Panopticon prison plan drawing7

You’re being tracked much more often in the physical world now, too. The mall tracking analogy I used before is actually happening in real life—except it’s not a tracking dart, it’s your cell phone. Our smartphones are constantly broadcasting wireless signals, looking for things to connect to via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. These signals include a unique ID to be used for communication, but that unique ID can also be used to recognize your phone (and therefore you). Mobile phone makers started using ever-changing, random IDs to combat this.

But you can’t change your face. Video cameras are everywhere now. While these systems were originally used for anti-theft monitoring and short-term recordings to be used in case of a robbery, they are now being connected to facial recognition systems to track where you go, how long you look at that end cap sale, how often and when you come to the store, and so on. And like web tracking, these systems’ third-party companies correlate this data across multiple stores and locations. These systems are all over the place in China and the United Kingdom. People in China can pay for food at vending machines and ride public transit simply by presenting their faces.

Several companies are now marketing systems that will use high-resolution video cameras to scan a scene to find all the license plate numbers it can see. The system records each plate number along with the time and place it was seen. These cameras are being mounted on utility poles, traffic lights, overpasses, and even police squad cars as they patrol. This information is hoovered up and shared with other agencies, creating a massive database of millions of cars. The timestamp and location information can be used to track where you go, identify your travel patterns, and even (potentially) track who you associate with. While this could obviously be useful finding who was near the scene of a crime and where those people live and work, it could just as easily be used to track an ex-wife, patrons of a gun show or a Planned Parenthood, or people attending a political protest.

I know it sounds hyperbolic, but we are truly living in an era of constant, global surveillance. Our “institution” is not just the virtual world, but increasing the real world, as well—and the watchmen are numerous. Unlike the 18th century, we have the computing power to actively monitor a large swath of the populace in real time. And with massive data storage facilities, our watchmen can record massive quantities of our activity, review it later at their leisure, and store it effectively forever.

Arguing that you don’t care about privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.8

We all have aspects to our lives that are private. Why are there doors on bathrooms? Why do people sing in the shower? Why do we have bumper stickers that say “dance like no one is watching”? Privacy is a basic human right and is fundamental to any healthy society. We act differently when we’re watched—not because we’re doing anything wrong but because we all need safe spaces to express ourselves. And as a famous Roman poet once said: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes, which roughly translates to “who watches the watchers?”.

If you’d rather read than watch a video, then check out world-renowned security expert Bruce Schneier’s essay on the value of privacy:

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2006/05/the_value_of_pr.html

On the Ethics of Ad Blocking

The business model for most of the Internet revolves around advertising, which in and of itself is not a bad thing. It may be an annoying thing, but passive advertising isn’t actually harmful. Passive advertising is placing ads where people can see them. And savvy marketers will place their ads in places where their target audiences tend to spend their time. If you’re targeting middle-aged men, you might buy ad space on fantasy football or car racing websites, for example. If you’re targeting tween girls, you might buy ad space on any site that might feature something about Taylor Swift or Ed Sheeran. And if it stopped there, I don’t think many of us would object—or at least have solid grounds for objection. After all, this advertising is paying for the content we’re consuming. Producing the content costs money, so someone has to pay for it or the content goes away.

Unfortunately, online marketing didn’t stop there. On the Web, competition for your limited and fickle attention has gotten fierce. With multiple ads on a single page, marketers need you to somehow focus on their ad over the others. And being on the Internet (and not a printed page), advertisers are able to do a lot more to grab your attention. Instead of simple pictures, ads can pop up, pop under, flash, move around, or float over the articles you’re trying to read. Worse yet, ad companies want to be able to prove to their customers that they were reaching the right people and that those people were buying their product. This makes their ad services far more valuable, meaning they can charge more for the ads.

Enter the era of “active advertising.” Today, you’re not just watching ads—those ads are now watching you back. The code that displays these ads is tracking where you go and what you buy, building up profiles on you and selling those profiles to marketers without your consent. Furthermore, those ads use precious data on cell phones and take a lot of extra time to download regardless of what type of device you use. And if that weren’t bad enough, ad software has become so powerful, and ad networks so ubiquitous and commoditized, that bad guys are now using ad networks to distribute malware. It’s even spawned a new term: malvertising .

Over the years, browsers have given users the tools they need to tame some of these abuses, either directly in the browser or via add-ons. It’s been a cat-and-mouse game: when users find a way to avoid one tactic, advertisers switch to a new one. The popular modern tool in this toolbox is the ad blocker. These plugins allow the user to completely block most web ads. Unfortunately, there’s really no way for ad blockers to sort out “good” advertising from “bad” advertising. AdBlock Plus (one of the most popular ad blockers) has attempted to address this with their “acceptable ads” policy, but it’s still not perfect.

But many web content providers need that ad revenue to stay afloat. Many websites are now detecting ad blockers and either nicely asking people to “whitelist” the website (allowing their site to show you ads) or in some cases actually blocking the content unless they turn off ad blocking. In a few cases, you have the option to subscribe (i.e., pay them money directly).

So…what’s the answer here? As always, it’s not black and white. I fully understand that websites need revenue to pay their bills. However, the business model they have chosen is ad-supported content, and unfortunately the ad industry has gotten overzealous in the competition for eyeballs. In the process of seeking to make more money and differentiate their services, they’re killing the golden goose. Given the abusive and annoying advertising practices, the relentless and surreptitious tracking of our web habits, the buying and selling of our profiles without our consent, and the lax policing that allows malware into ads, I believe that the ad industry only has itself to blame here. We have every reason to mistrust them and every right to protect ourselves. Therefore, I think that people are fully justified in the use of ad blockers—and I wholeheartedly recommend that you use them.

That said, websites also have the right to refuse to let us see their content if we refuse to either view their ads or pay them money. However, I think in the end they will find that people will just stop coming to their websites if they do this. (It’s worth noting that some sites do survive with voluntary donations, like Wikipedia.) Therefore, something has to change here. Ideally, the ad industry will realize that they’ve gone too far—that they must stop tracking our online pursuits and stop trafficking in highly personal information without our consent—and voluntarily change their ways. But it hasn’t happened yet.

The bottom line is that the ad industry has itself to blame here. They’ve alienated users, and they’re going to kill the business model for most of the Internet. They must earn back our trust, and that won’t be easy. Until they do, I think it’s perfectly ethical (and frankly safer) to use ad-blocking and anti-tracking tools.

Information Leakage

As you can see, it’s hard to hide your tracks as you surf the Web. But there are even more ways in which your web surfing is tattling on you.

As we’ve discussed in early chapters, when you enter a web address into your browser like “amazon.com”, your computer must actually convert that human-friendly hostname to a computer-friendly IP address. This is done via the Domain Name Service (DNS). Your computer is usually given its DNS provider automatically when it’s connected to your home network at the same time that your computer obtains its local IP address. Your home router is in charge of this, and it all happens behind the scenes without you having to do anything. Your router usually gets its DNS service from your Internet service provider, in much the same manner. So, when your computer asks the router to convert “amazon.com” to an IP address, your router turns around and asks your ISP to do it.

Unfortunately, unlike much of our regular communication now on the Internet, DNS queries are not encrypted by default. And because we have rolled back regulations on what your ISP can track, they are more than happy to keep information about every website you visit and sell it to the highest bidder.

To fix this, you need to choose another DNS provider—preferably one that supports encrypted DNS queries so that your ISP can’t see what hostnames you’re looking up. The best way to do this is to just alter the DNS provider on your router—change the default to something better. This means every device in your home network will inherit this setting. However, for smartphones and laptops that will leave your home network, you’ll want to change this setting on these devices, as well.

There’s another obscure way that your computer rats you out, and it’s actually part of the most basic part of the Internet: Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). It’s just trying to be helpful really, but in doing so, it’s oversharing. When you enter a web address (http://something.com), your web browser hands over lots of potentially helpful information to the website you visit including the website you just came from. This data is passed to the new website through the Referer header (yes, it’s misspelled… a classic Internet-ism). Why? Well, sometimes websites work together, so it’s helpful for them to know where you came from. It’s also a way to pass data on to the next site. But if the website isn’t careful, it can share too much information (TMI).

Referer: https://www.healthcare.gov/see-plans/85601/results/?county=04019&age=40&smoker=1&pregnant=1&zip=85601&state=AZ&income=35000

Take a close look at the info contained in there. Those are parameters that the user had submitted to the website, probably in a form page. As a quick-and-dirty way to pass that data around to other pages on the healthcare.gov site, it simply included the form values in the web address, which would show up in the Referer header. But as soon as you leave healthcare.gov and go to amazon.com, let’s say, Amazon would get all that info, as well—and you wouldn’t know it. This bug was fixed, but who knows what other websites might be oversharing like this? Luckily, at least one browser maker is automatically cleaning up this for you. We’ll discuss that shortly.

Speaking of web forms, I need to let you in on another dirty little website data-slurping secret. How often have you started filling in a web form—maybe to sign up for an account or to answer a survey—and then changed your mind because you felt it was getting too personal or something? So you closed the page without hitting Enter or Submit. No harm done, right? Maybe not. Some websites are now recording all the data you enter, even if you never submit the form. Web technology that can be used to make sure that you entered good data (e.g., a valid telephone number or email address) can just as easily be used to save that data. It feels really slimy, but it’s actually being done on some sites. So, just be aware.

Choose Your Weapon

Your primary interface to the wild and woolly Internet is the venerable web browser. For many people, the web browser is the Internet. So, it stands to reason that you would want to pick the safest browser to do your web surfing.

There are at least two primary aspects to safety when it comes to web browsing: security and privacy. A secure browser will do whatever it can to prevent you from visiting bad websites, warn you against entering sensitive information on insecure pages, identify sites that aren’t encrypted, and strictly enforce policies that prevent malvertising and other malicious web exploits. A privacy-protecting browser will help protect your privacy by severely limiting the ability of websites and marketers to track you.

According to NetMarketshare, the most popular browsers as of this writing are Chrome (69 percent), Internet Explorer/Edge (13 percent combined), Firefox (8 percent), and Safari (4 percent). Internet Explorer and Edge are the default browsers on Windows PCs,9 and Safari is the default browser on Apple Macintosh computers. Firefox (which rose from the ashes of Netscape Navigator) is the only browser in the top four that is open source (meaning the source code is freely available for inspection). Firefox is made by the nonprofit Mozilla Foundation, which is funded primarily by search royalties (accepting money to set a particular search engine as the default). Despite very different aesthetics, at the end of the day, all four of these browsers do basically the same thing: they show you web pages. So, how do you know which is safest?

Most Secure Browser

Let’s just get this out of the way now: it’s almost impossible to know which browser is the most secure. This is largely because all of these browsers are constantly rolling out new security-related features, fixing security-related bugs, and generally trying to claim the title of “most secure.” That’s a good thing—they’re competing to be the best, so we all win. There are dedicated hacking contests to reveal bugs in browsers, but it’s hard to say whether the number of bugs found in these contests really reflects the security of the browser. How likely were bad guys to find these bugs? How severe were the bugs? What about the bugs they didn’t find? These hackathons also don’t address factors like how quickly the browser maker fixes their bugs and whether the browser is smart enough to self-update (because if you don’t have the latest version, you don’t have the bug fixes). It’s really hard to compare the relative security of web browsers.

However, if I had to pick a winner here, I’d probably have to choose Chrome. Google is doing some fantastic work in the realm of computer and web security. That said, I think Firefox and Safari are also very secure browsers. And you could argue that because Firefox is open source, it can actually be audited by cybersecurity experts—unlike the other three major browsers. Ideally, this third-party vetting leads to less bugs.

Most Private Browser

Unlike security, there are significant and important differences between the four major browsers when it comes to privacy. And this (to me) is the real deciding factor.

While Google has been a true leader in terms of security, it’s pretty much the worst in terms of privacy. Its whole business model revolves around advertising (Google makes about 90 percent of its money from ads10). And that leads to an enormous conflict of interest when it comes to protecting your personal data and web surfing habits. Apple has gone out of its way to basically be the anti-Google, making it a point of pride to collect as little data on their users as possible (and causing a collective freak-out by advertisers because of technology that limits tracking). But Firefox is also doing some great work in this area, and adding more privacy features all the time.

So, who’s the winner in terms of privacy? Today, I’d say it’s a toss-up between Firefox and Safari, with Chrome being dead last. Edge is somewhere in between, but with Microsoft’s recent penchant for collecting user data, I would put it closer to Chrome. Chrome has been trying to tame obnoxious ads with a built-in ad-blocking technology, but it’s important to note that it does nothing, really, to prevent tracking. And even if Google were protecting you from other companies tracking you, you should assume that anything you do in the Chrome browser is known to Google. In fact, as of June 2020, Google is being sued for continuing to track its users while in “incognito mode.”11

And the Winner Is…

Based on everything I’ve found in my research, I personally choose Firefox as my go-to browser. No browser is 100 percent secure, and it’s hard for even the most erstwhile browser to completely protect your privacy. But I think Firefox, on balance, is the best of the bunch.

Beyond the Big Four

The Brave browser is a relatively new, open source browser built for privacy, with built-in ad blocking and tracking protection. However, in a move to try to acknowledge the need for ad-based revenue, it also has a mechanism to insert its own ads, which opens up a lot of issues.

The Tor Browser is all about privacy. In fact, it tries to achieve true anonymity (though that is extremely difficult to do in practice). It’s based on Firefox and builds in several kick-butt privacy tools that are too technical to sum up here. But if you really need to surf privately, you should give the Tor Browser a serious look.

Summary

Surfing the Web is one of the main ways in which we interact with our computer and the Internet, and as such, it’s one of the most important things that we need to secure.

Our web security system is based on special digital certificates that are used to (a) prove that you’re talking to who you think you are and to (b) encrypt the communications between you and the other end. While the certificate authority system has flaws, it’s the best we have right now, and it’s good enough for most things.

We’ve learned why and how your actions are tracked via the Web. Simple things like web cookies and nearly invisible images can be used to track everywhere you go, reporting the information back to central locations run by marketing companies. Worse yet, the configuration information your browser provides to every website can be used to recognize you.

We also saw how your browser leaks information about you in several other ways: DNS lookups, Referer headers, and web forms.

When choosing a web browser, you need to consider both security and privacy. While all browsers attempt to be secure, one a few are really trying to protect your privacy.

Checklist

I have to give one caveat here. Many security and privacy tools can cause some websites to act strangely or even fail to work at all. This is an unfortunate side effect of trying to protect yourself. When you come to a website that no longer seems to work properly, you may need to try adding a special exception for that website or disable some security plugins temporarily. I realize this is painful. As with all security choices, you need to weigh safety against convenience. I would try to be safe by default and make security exceptions only when necessary.

Browsers change their screen layouts all the time. These screenshots were accurate at the time of this writing, but you may find them a little different. Use the search feature within the browser’s settings/preferences window to find these settings if they move around.

Tip 7-1. Install Firefox

Choosing a good web browser is important. For me, the clear choice to maximize both security and privacy is clear: Firefox. While Google’s Chrome browser is very secure, they have a severe conflict of interest with regard to your privacy. Google potentially has access to everything you do in that browser, and that should give you the creeps. Google already knows way too much about us.

You do not need to sign up for a Firefox account to use Firefox. You can just bypass/close/skip the sign-up screens, if you’re presented with any. But if you use Firefox on multiple devices, having an account will allow you to synchronize your bookmarks, which can be very handy.

Download and install Mozilla’s Firefox browser: https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/new

Launch the web browser and go through first-time setup. If asked whether you want to make Firefox your default browser, say yes. This may take you to a system preference where you have to change the default setting.

If asked, you will probably want to go ahead and import bookmarks, favorites, and so on, from your current web browser. However, do not import passwords. LastPass has that covered.

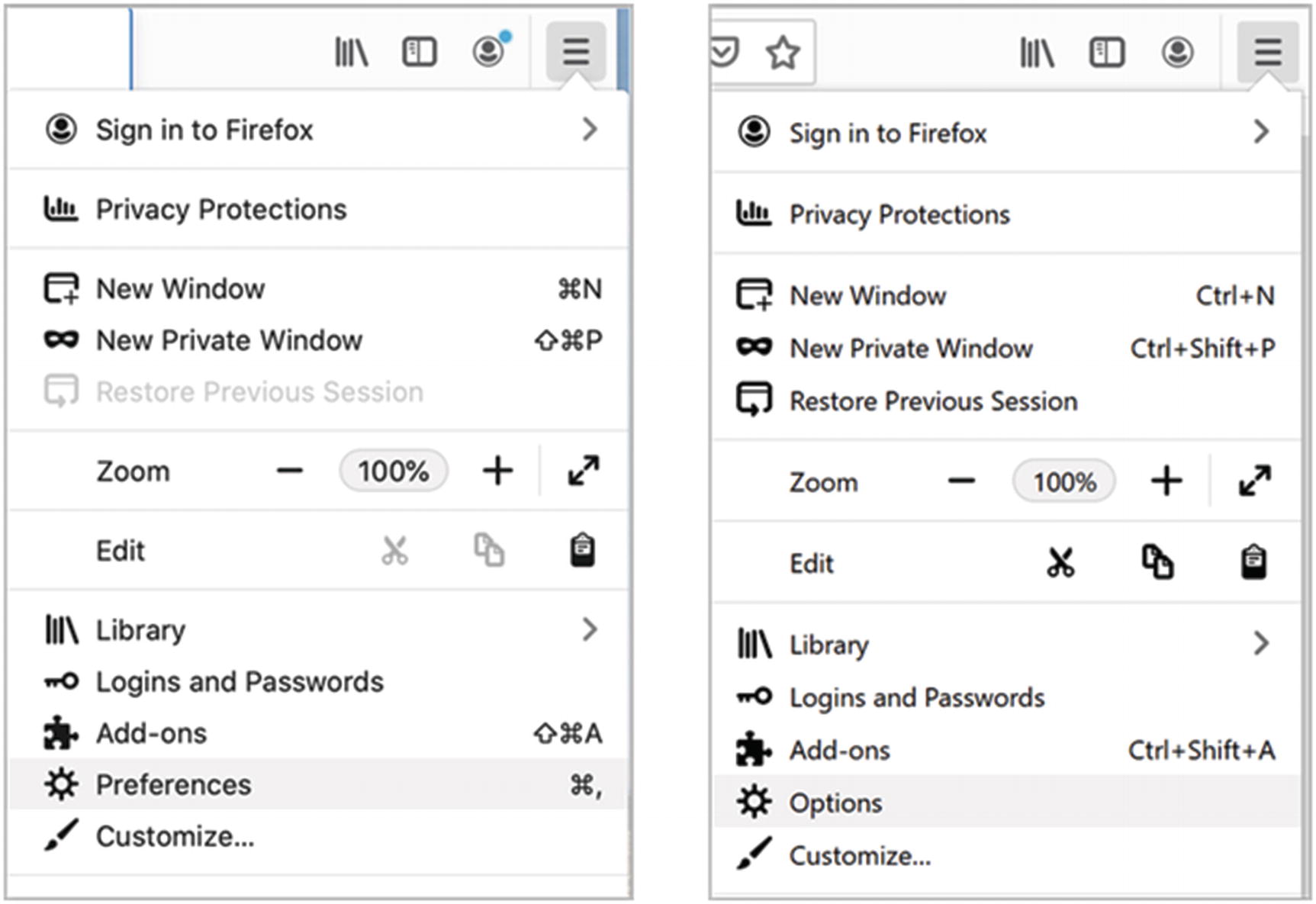

Tip 7-2. Configure the Security and Privacy Settings on Firefox

- 1.

Open the Firefox menu at the upper-right corner of the browser window. Click Preferences (Mac) or Options (Windows) (Figure 7-7).

Firefox preferences (left, Mac; right, Windows)

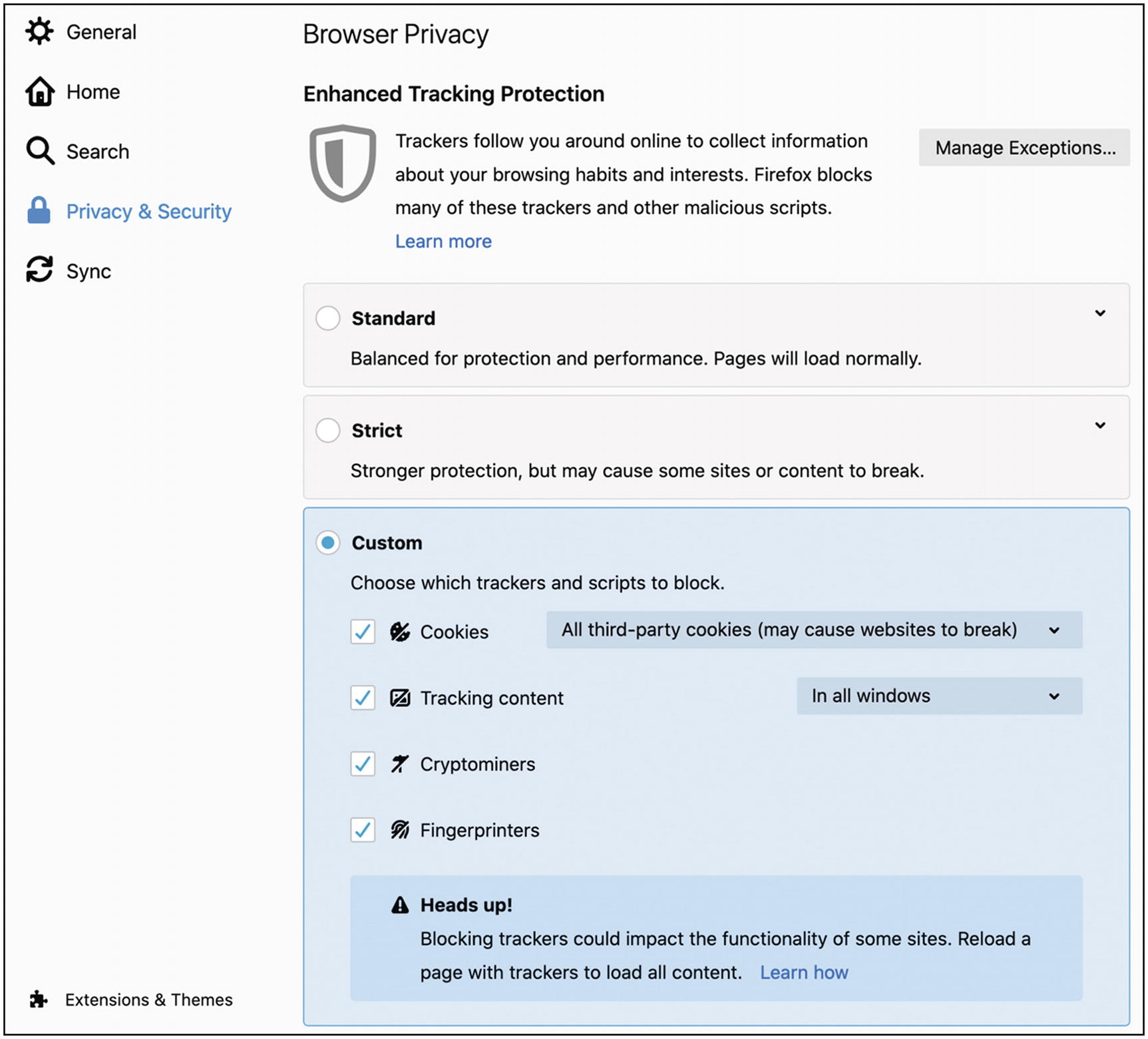

- 2.

Select the Privacy & Security tab at the left. Under “Enhanced Tracking Protection”, you can either select “Strict”, or you can create a custom set of security and privacy settings. I personally use “custom” so I can block all third-party cookies. This is slightly more strict than “Strict” (Figure 7-8).

Firefox Enhanced Tracking Protection

- 3.

I would always send the “Do Not Track” signal just to register your desire to be left alone, but realize that this is mostly symbolic—most websites that want to track you will ignore this, sadly (Figure 7-9).

Firefox Do Not Track setting

- 4.

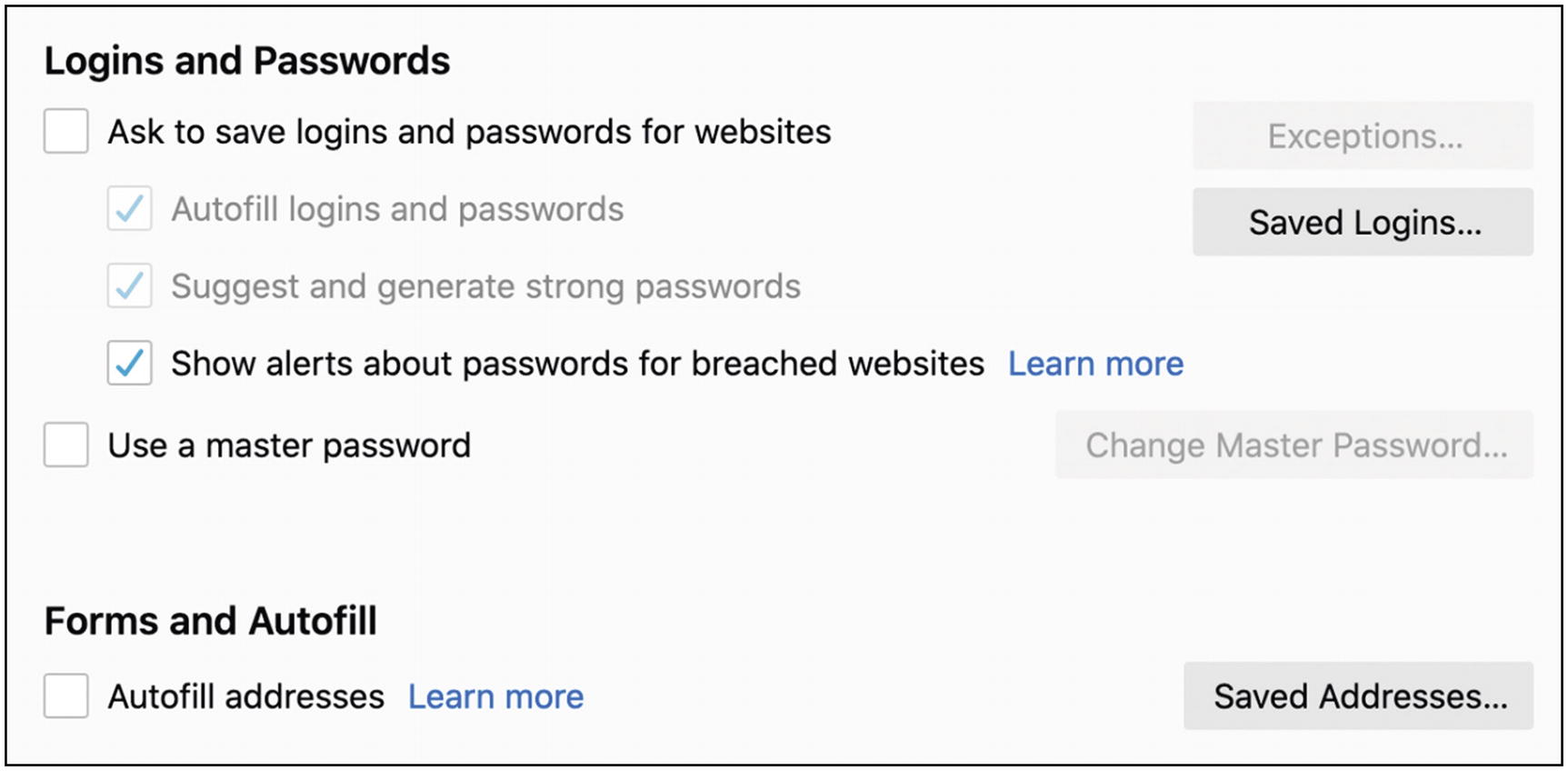

Under Logins and Passwords, be sure to uncheck “Ask to save logins and passwords”—we’ll be using LastPass for this. And if there are any saved passwords under “Saved Logins…” be sure to remove them all (after you copy them to LastPass, of course). LastPass will also handle filling in mailing addresses for you, so you can uncheck the “Autofill addresses” option, as well (Figure 7-10).

Firefox forms and passwords settings

- 5.

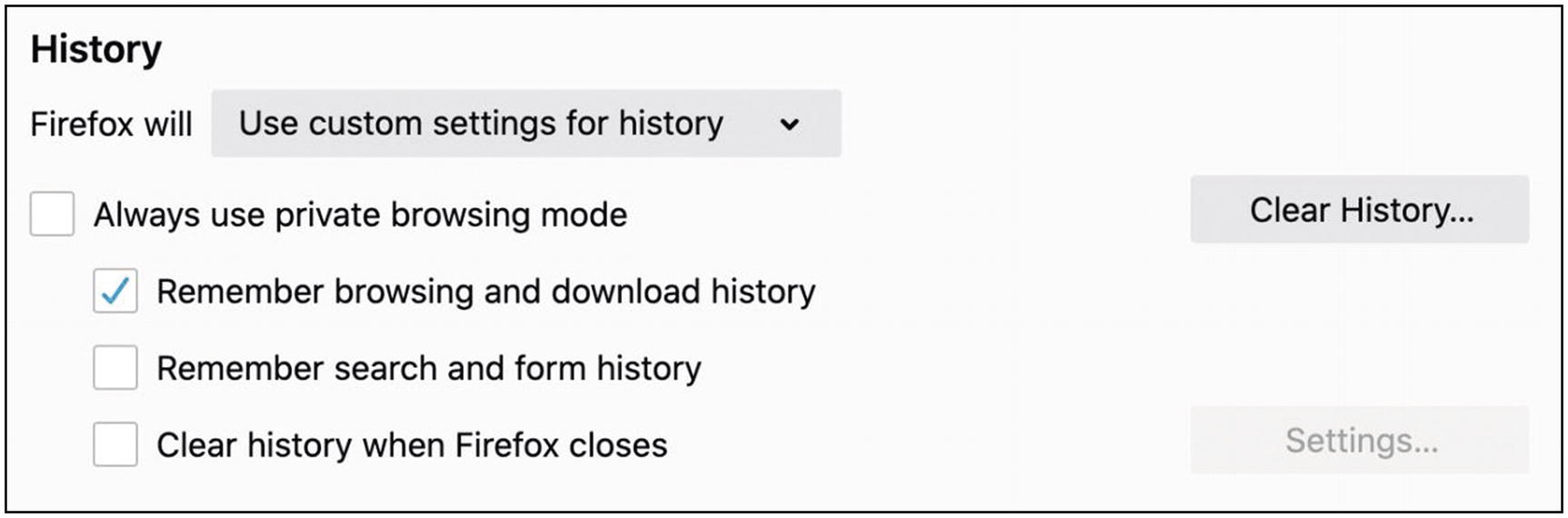

Under the History section, you can feel free to use whatever settings you’re most comfortable with here. To the best of my knowledge, Mozilla does nothing with this saved information. You probably don’t want to always use “private browsing mode”, but only as needed. This is discussed in Tip 7-10 (Figure 7-11).

Firefox History settings

- 6.

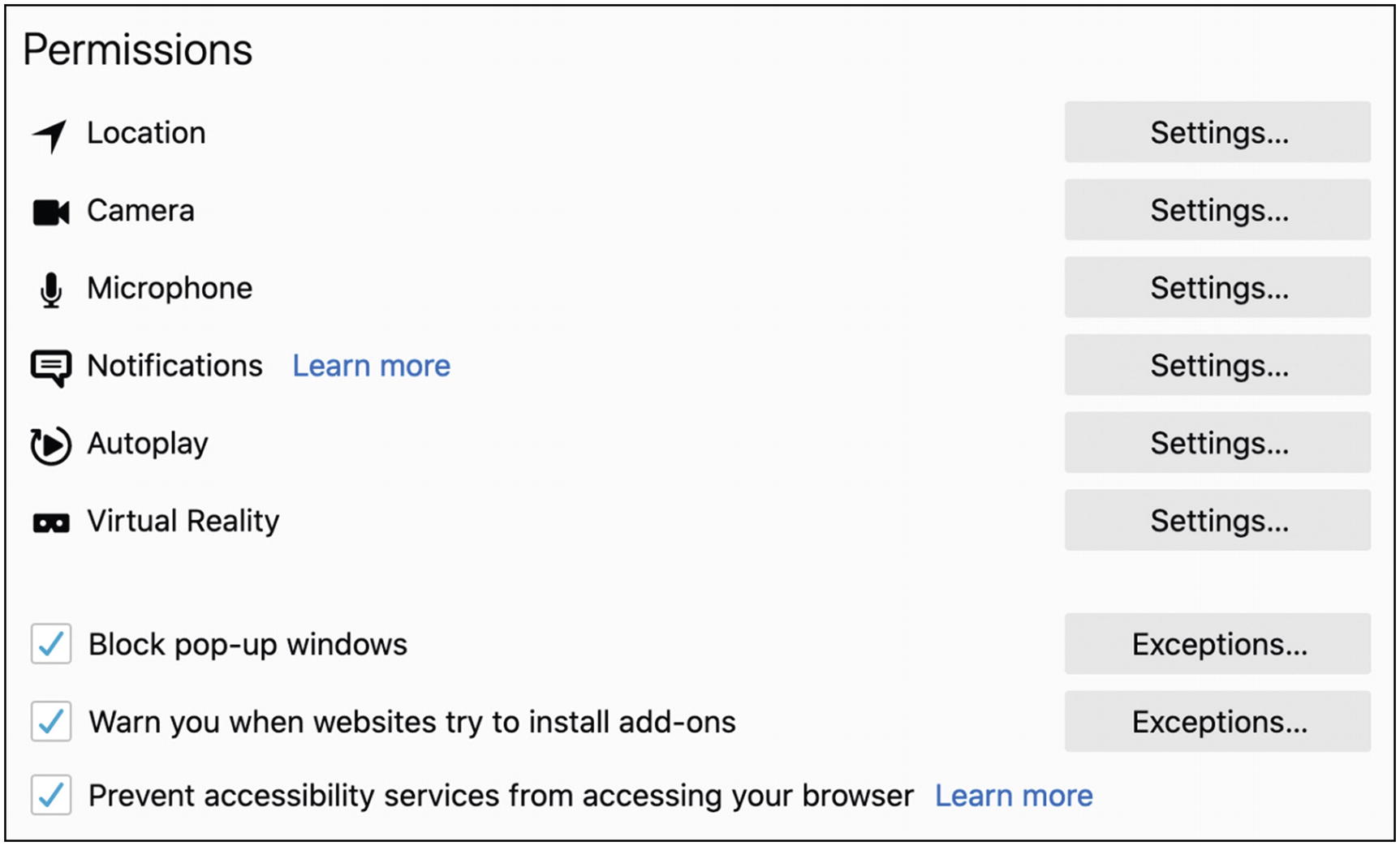

Next, find Permissions (Figure 7-12). There are several settings here, and you should look at each of them individually. By far the safest thing is to block all requests to access your location, camera, and microphone. However, that will break some websites. Firefox will ask you for permission whenever a website requests access to these items, so you can leave these settings at the default. Just know that you can permanently deny or allow any site here. Below the Permissions settings, you should check all three boxes. This may require you to restart Firefox.

Firefox Permissions settings

- 7.

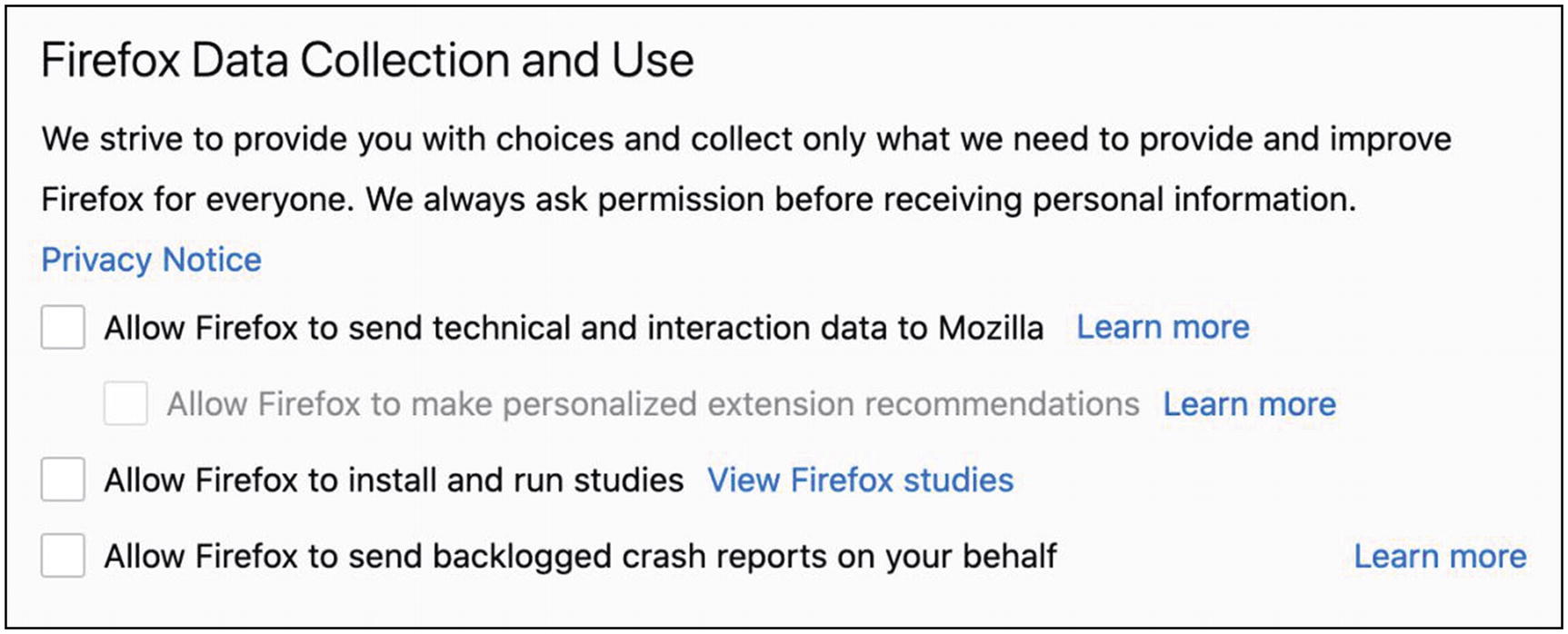

Find “Firefox Data Collection” (Figure 7-13). You can decide what you want here. For maximum privacy, you should share nothing. But for Mozilla to improve its products, it has a legitimate need for some user data. But maybe they can just get that from someone else.

Firefox Data Collection and Use settings

- 8.

Finally, find the section “Deceptive Content and Dangerous Software Protection” under the “Security” section (Figure 7-14). I’m not sure how effective this is, but it’s worth a shot. I would check all the boxes.

Firefox Security settings

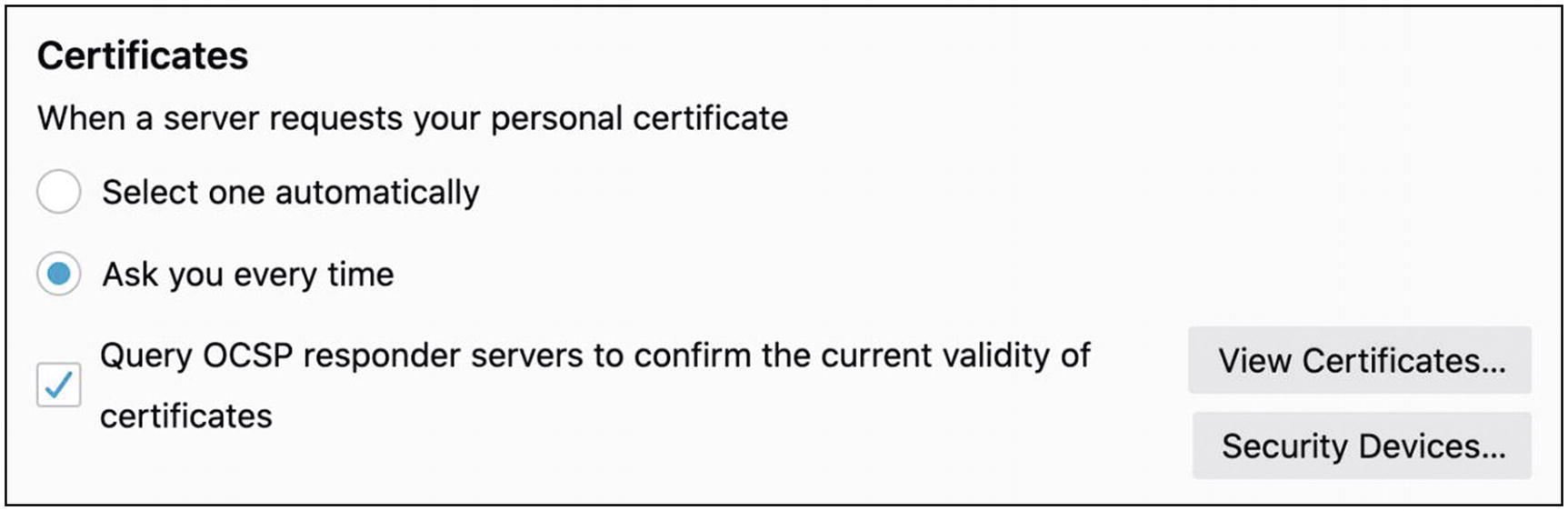

- 9.

Finally, under “Certificates”, you should have it ask you every time and query OCSP servers. This is protection against bad certificates, which we discussed in the chapter (Figure 7-15).

Firefox Certificates settings

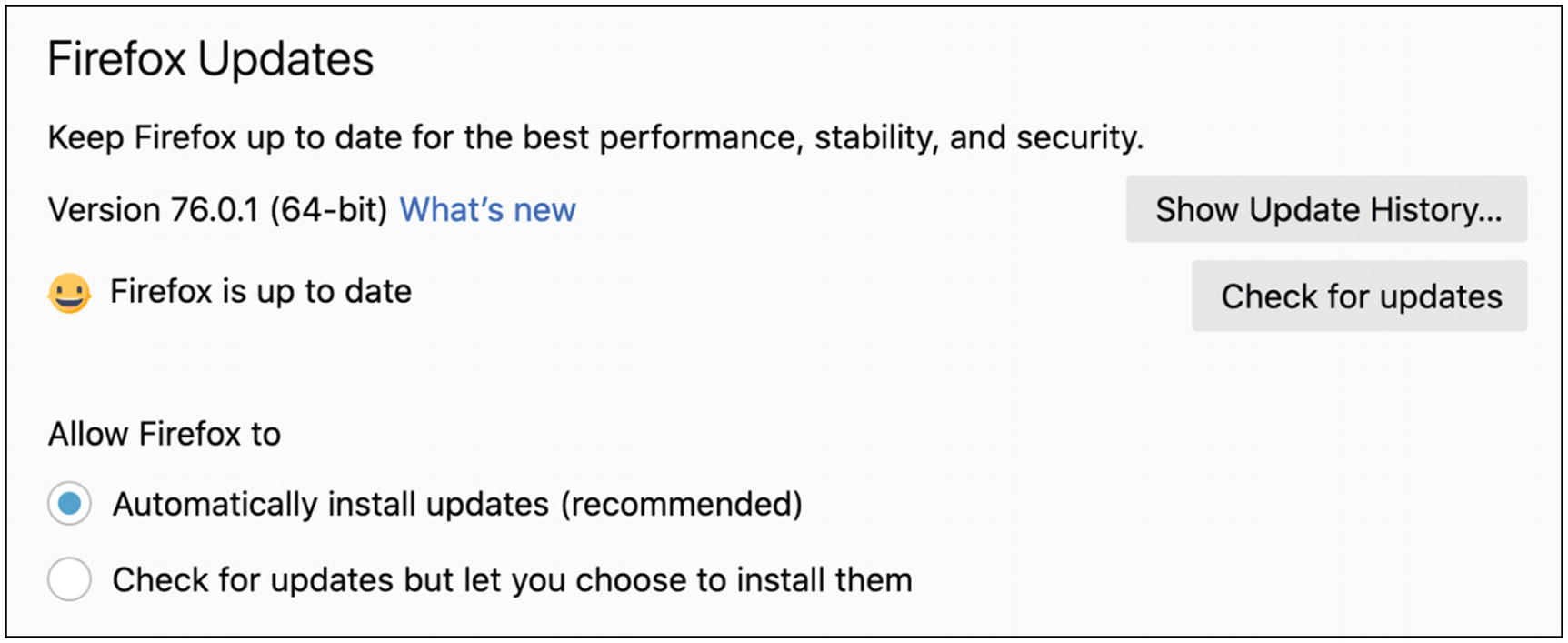

- 10.

Finally, go back to the “General” tab at the left of the Preferences/Options page. Check the box to have Firefox automatically install updates (Figure 7-16).

Firefox Updates settings

Tip 7-3. Remove All Unnecessary Add-ons

Web browsers have become very flexible, allowing you to add all sorts of fun and useful features via plugins, add-ons, and extensions. Unfortunately, these extras, many of which are free or get installed with other software, can open security holes and seriously invade your privacy. Avoid them unless you really need them. (In the next tip, I’ll give you some add-ons that will significantly enhance your security and privacy.) If you have any trouble removing an add-on, try searching for remove <add-on name> in your web browser. Some of these add-ons are tenacious and hard to remove (and these are the ones you most assuredly need to remove).

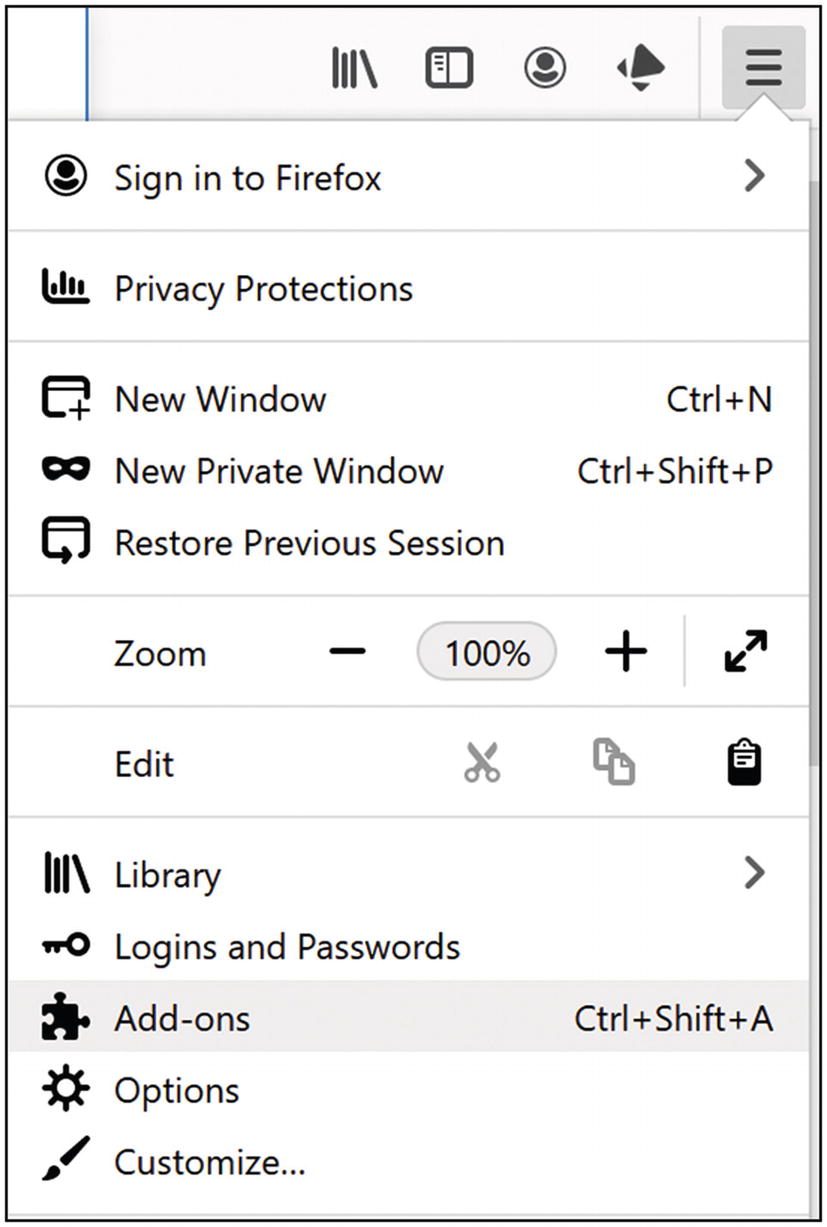

- 1.

To remove an unwanted add-on in Firefox, first open the Add-ons menu from the general Firefox menu (Figure 7-17).

Firefox Add-ons menu

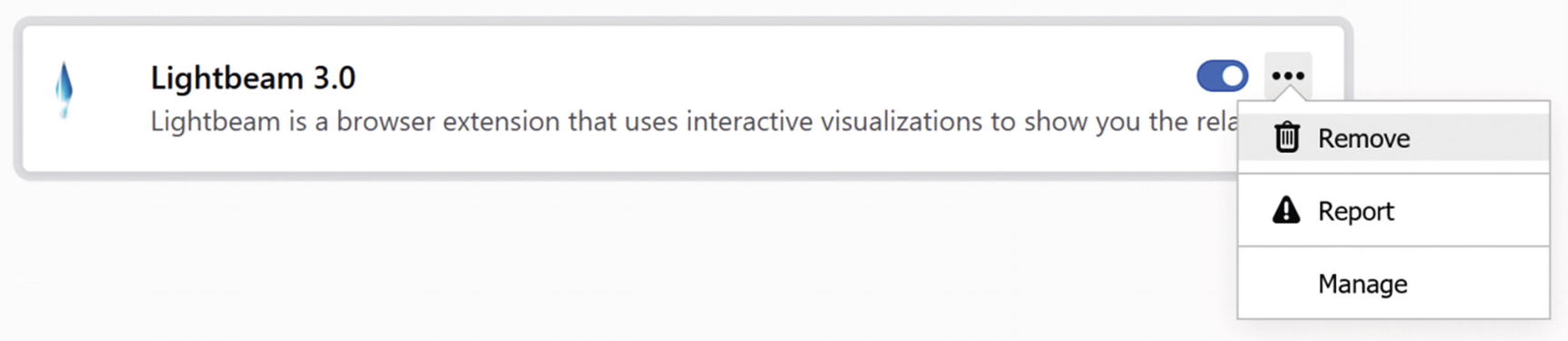

- 2.

Select the Extensions tab at the left. Find the add-on that you want to remove and click the Remove button, under the little menu at the right. (If you’re not sure, just click the Disable button for now and remove it later when you’re sure.) Figure 7-18 shows an example.

Firefox extension example

- 3.

You may need to restart your browser to complete this. If you have multiple add-ons to remove, you can remove them all and then just restart the browser once.

Tip 7-4. Change the Default Search Option to DuckDuckGo

To set DuckDuckGo as your default web browser search engine, the easiest way is to just install the DuckDuckGo Privacy Essentials plugin. Not only will this make DuckDuckGo your default search engine, it will also add some great privacy-protecting features to your browser. See the next tip for help with installing this and other great plugins.

Tip 7-5. Install Security and Privacy Add-ons

Some add-ons actually enhance your security and privacy by preventing websites from loading annoying ads and installing tracking cookies. (In fact, these plugins can significantly increase page-loading speed by avoiding lots of stuff you don’t need.) I recommend installing all of the following extensions. They each perform a slightly different function, though there is some overlap. I will walk you through installing one extension. The rest will follow the same procedure.

The nature of most of these plugins is to block or restrict unwanted content. This can sometimes break websites that haven’t been properly designed for the possibility that people might not want annoying ads, tracking cookies, and so on. If you find a website that is not working properly or somehow acting funny, you might try temporarily disabling some of these plugins. Or you could also use the browser provided by Mac OS (Safari) or Windows (Edge) as a backup.

- 1.

Open the Add-ons menu, as we did in the earlier tip.

- 2.

Using the Add-ons search bar where it says “Find more extensions” (not the regular browser search bar), search for Privacy Badger and hit Enter.

- 3.

The top choice should be Privacy Badger from EFF. Click the name of the add-on to select it. Then click the “Add to Firefox” button. This will bring up a confirmation dialog; click Add.

Privacy Badger : We just did this one, but wanted to make sure that anyone scanning this list would see it.

HTTPS Everywhere : Another great plugin from EFF that attempts to use HTTPS wherever possible. Some sites can do HTTPS but won’t do it unless you ask—this plugin makes sure that your browser asks for HTTPS by default. Note that some sites with mixed content (HTTP and HTTPS on the same page) may not work properly with this plugin, so you might try disabling this one first if you’re having trouble.

LastPass : Even though we already installed LastPass in an earlier chapter, the browser plugin was installed only for the browsers you had installed at that time. If you just now installed Firefox, then you’re going to need to install the LastPass plugin for Firefox.

DuckDuckGo Privacy Essentials : Not only will this install some excellent privacy and security tools, it will set your default web search to be DuckDuckGo.

uBlock Origin : This plugin blocks website advertising (and therefore tracking). You should note, however, that most free websites stay in business by getting money from advertisers. You may want to consider enabling ads from websites that you want to explicitly support. But keep in mind that it’s not just about ad revenue for your favorite site—it’s also about protecting your privacy and securing your computer from malvertising. (Don’t install “uBlock”—that’s a totally different add-on. You want uBlock Origin. It’s an interesting story—you might look it up in Wikipedia.)

Decentraleyes : It’s a little hard to describe what this one does in a few sentences. But many of the web pages you visit download a bunch of little helpers in the background to do fancy things. Just the act of fetching these little snippets of code can give away information about sites you visit—this plugin contains many of the most popular helpers so your web browser doesn’t need to get them.

Tip 7-6. Always Go to the Source for Downloads

It may surprise you that legitimate software download sites often install things you don’t want and didn’t ask for. Sites like Download.com, BrotherSoft, Softonic, Tucows, and SourceForge will often install trial offers, adware and other junk, along with the software you actually wanted. This is how these sites make money.

But it’s actually worse than that. There have been several cases where these bundle installers have been hacked to install nasty malware, too. It’s just not safe to use these sites anymore.

Always, always go to the source for software downloads. Find out who makes the software and go directly to their website. Or, better yet, get the app from the Apple App Store or the Microsoft Store. These apps have gone through at least some security and privacy vetting. The vetting isn’t perfect, but it’s better than no vetting.

Tip 7-7. Be Careful on “Shady” Sites

Some websites are just way worse than others when it comes to malware, and those sites tend to be associated with what some would call vices…porn, gambling, copyrighted movie and music downloading, and so on. I’m not here to judge. Just know that these sorts of sites tend to be worse than others, and the ones that are “free” are ones I’d worry about the most.

Tip 7-8. Beware of Pop-Ups Offering/Requiring Plugins

Some websites will ask/offer to install some malware checker or speed booster or video player. If you get a pop-up window that wants to install something, just close the window and walk away. If the plugin is something common like Flash, Java, Silverlight, or QuickTime, you should go directly to those websites to download and install the plugin. Then return to the original website and see if it works. The rule is: if you didn’t go looking for something or request it yourself, don’t install it.

Some of these website pop-ups will actually tell you that you’re already infected with malware or that your computer is having problems. They may sound dire and urgent, but don’t be fooled. They’re just playing on your fears. They’re almost surely scams or malware.

Tip 7-9. Opt Out Where You Can

This site has lots of great info: https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/2015/08/consumer-tips-top-ten-opt-outs

This site has a ton of information about what specific websites and real-world retailers collect and how to opt out:

Opting out of credit card offers: https://www.optoutprescreen.com

Opting out of online tracking: https://optout.networkadvertising.org

Opting out of Google “interest-based” ads: https://adssettings.google.com

National “do not call” registry: https://www.donotcall.gov/

Opting out of direct marketing mail and email: https://dmachoice.thedma.org

Tip 7-10. Use Private Browsing

- 1.

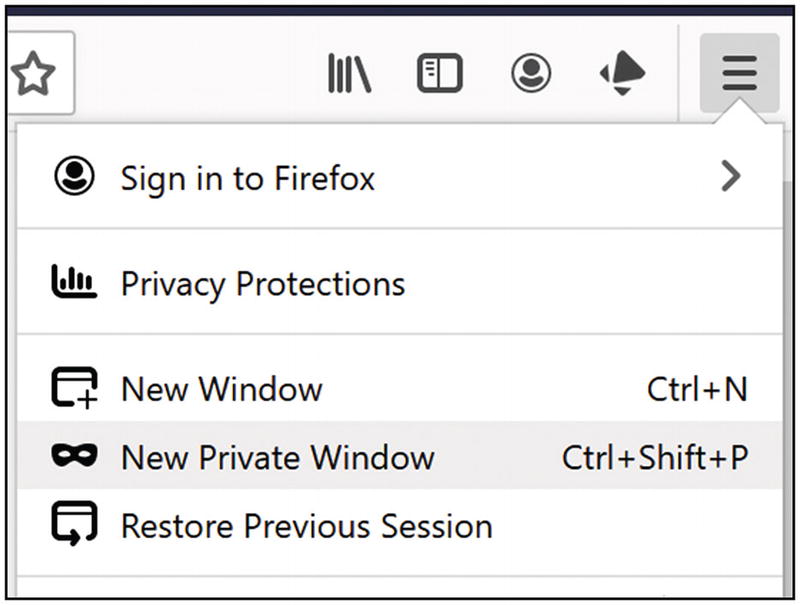

Open the Firefox menu and select New Private Window (Figure 7-19).

Firefox New Private Window menu

- 2.

Do your private browsing in this window. When done, just close this window and all (local) history of what you did in that window will be erased.

Tip 7-11. Change Your DNS Provider on Your Wi-Fi Router

Remember that DNS is the Internet’s “phone book”: it will convert a name (like amazon.com) to a number (an IP address). Today, most DNS lookups are not encrypted, meaning that your DNS provider—and any computers along the way—can see every website you go to. For this reason, it’s important that you choose a privacy-respecting DNS provider that supports encrypted DNS requests. By making this setting on your home Wi-Fi router, this means that all devices in your home will use this DNS service.

Unfortunately, changing any router setting can be tricky because every router’s admin page is a little different. I can’t give you a simple step by step for every possible router. In the previous chapter, I told you how to find your router’s admin IP address—use that same address to make these changes. You’ll need to look for the configuration for your Domain Name Service (DNS) server. It should be prepopulated with a couple addresses—a primary and a backup. The first entry is the one it will try most times, but if that one fails, it will try the second one. The default addresses almost surely belong to the DNS provider used by your Internet service provider (ISP).

Once you find these settings, remove the existing entries and add one of the two pairs. The options listed here are privacy-oriented (and will avoid using your ISP’s DNS, which is almost guaranteed to log every site you go to). Note, however, that unless you’re using a VPN, your ISP will still be able to see every IP address your computer communicates with and can use that to figure out where you’re going if it bothers to do a reverse lookup.

Basic:

1.1.1.1

1.0.0.1

Anti-malware (best for most people):

1.1.1.2

1.0.0.2

Anti-malware and Adult Content:

1.1.1.3

1.0.0.3

While not used much yet, you might want to go ahead and set the IP version 6 (IPv6) versions of these servers, as well:

Basic:

2606:4700:4700::1111

2606:4700:4700::1001

Anti-malware:

2606:4700:4700::1112

2606:4700:4700::1002

Anti-malware and Adult Content:

2606:4700:4700::1113

2606:4700:4700::1003

If you would like a different option, try Quad9: www.quad9.net.

Tip 7-12. Change Your DNS Provider on Your Laptop

If you have a laptop, you should also set your DNS settings there because when you’re out and about, you’re no longer using your home’s Wi-Fi router.

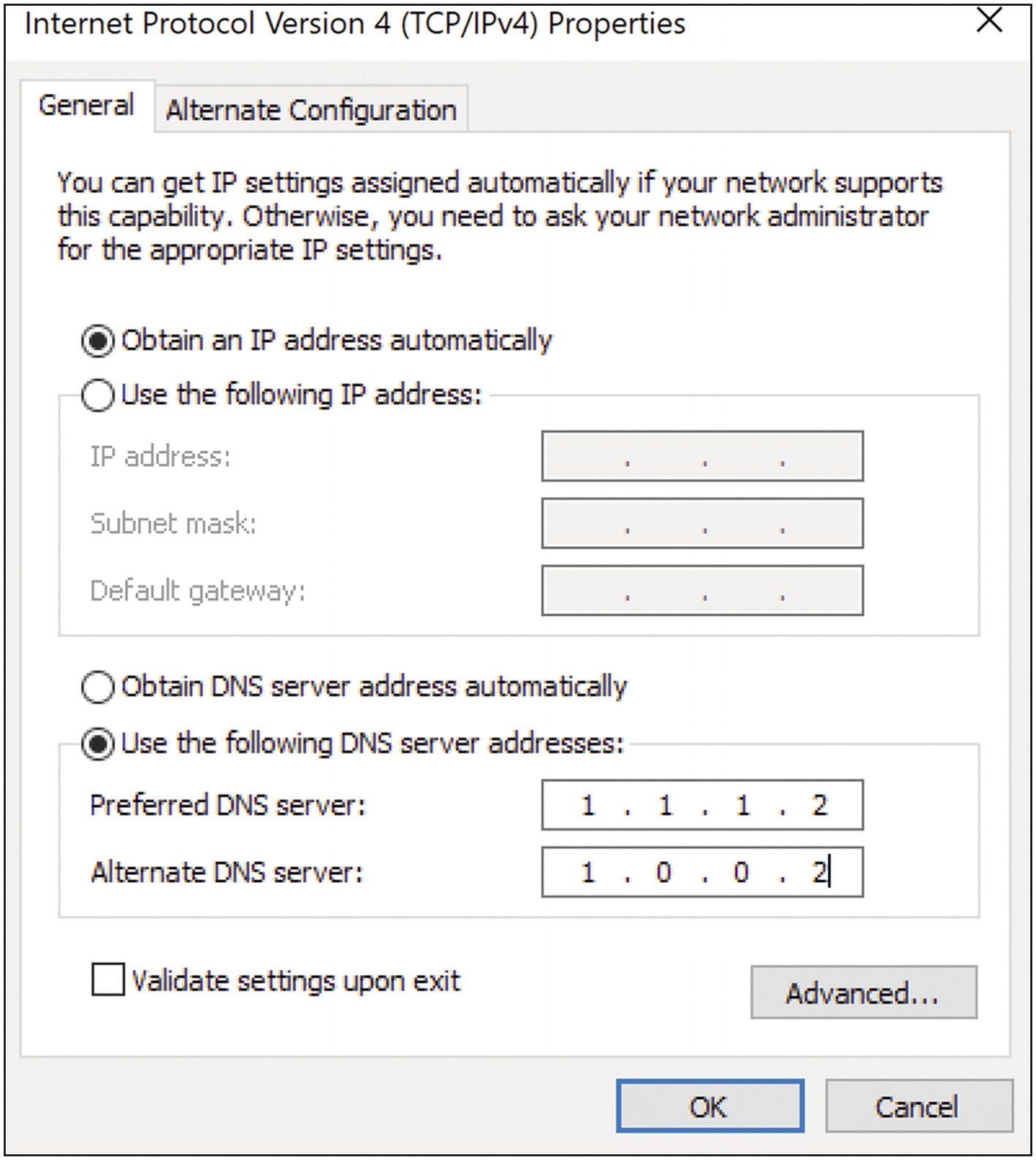

Tip 7-12a. Windows 10

- 1.

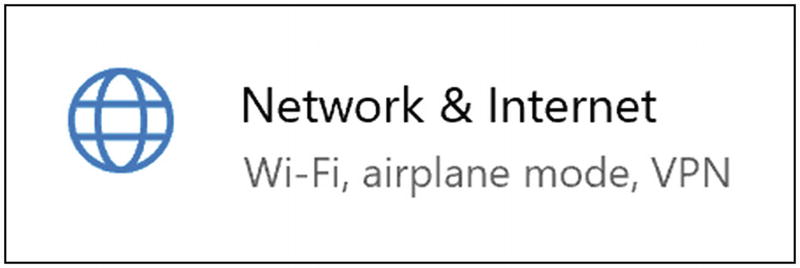

Open Settings. Click Network & Internet (Figure 7-20).

Windows 10 Network & Internet settings

- 2.

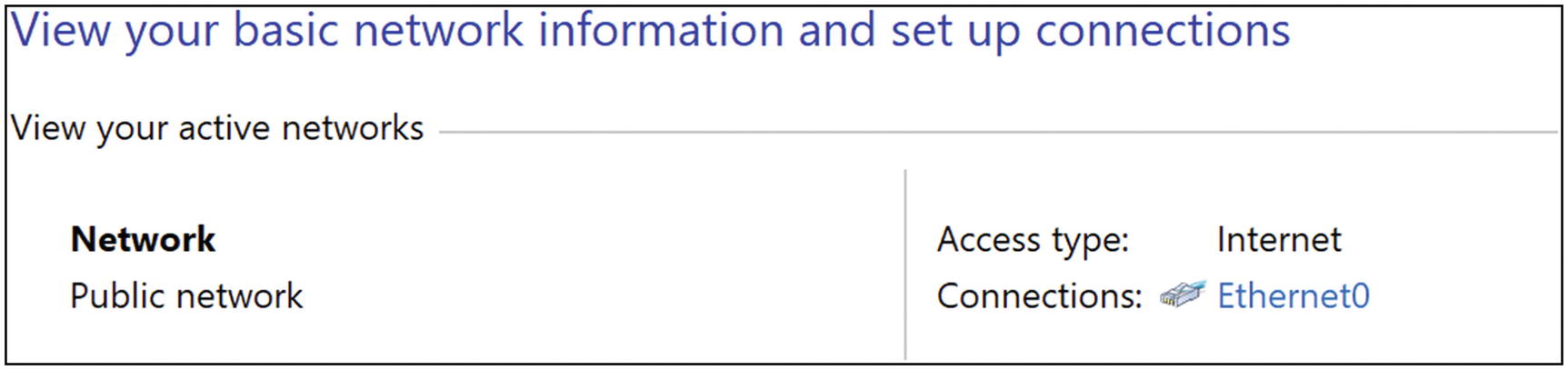

Find “Network and Sharing Center” and click it. You will then see your active networks. On a laptop, there will probably be just one (Wi-Fi), but you can (and should) change these settings for all the active networks. Just repeat this process for each listed connection (Figure 7-21).

Windows 10 active networks

- 3.

Click the blue link next to “Connections” to bring up the connection status. Click the “Properties” button at the lower left (Figure 7-22). Enter your admin password, if asked.

Windows 10 connection status

- 4.

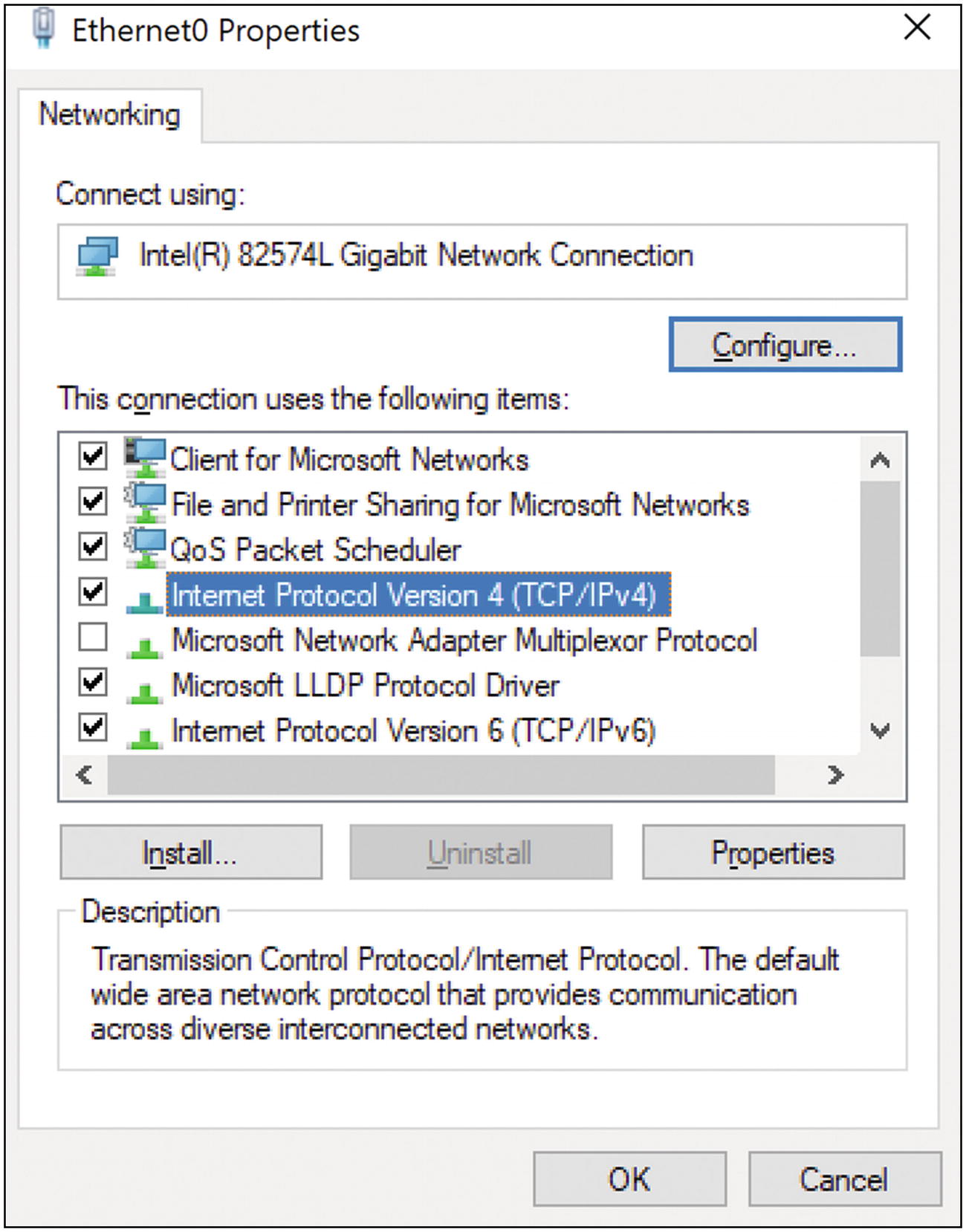

In the Properties window, select “Internet Protocol Version 4” and click the “Properties" button under the list (Figure 7-23).

Windows 10 IPv4 network properties

- 5.

Change the DNS server addresses to the ones you want (see the previous tip for info). You’ll need a primary and an alternate pair. In Figure 7-24 I’ve shown the Cloudflare addresses as an example. Click “OK” to save the settings.

Windows 10 example IPv4 DNS settings

- 6.

If you’d like to set the IPv6 DNS settings, select the “Internet Protocol Version 6” entry and click “Properties”. You can then set the IPv6 servers, using the information in the previous tip. The following example shows the Cloudflare settings. Click “OK” to save the settings (Figure 7-25).

Windows 10 example IPv6 DNS settings

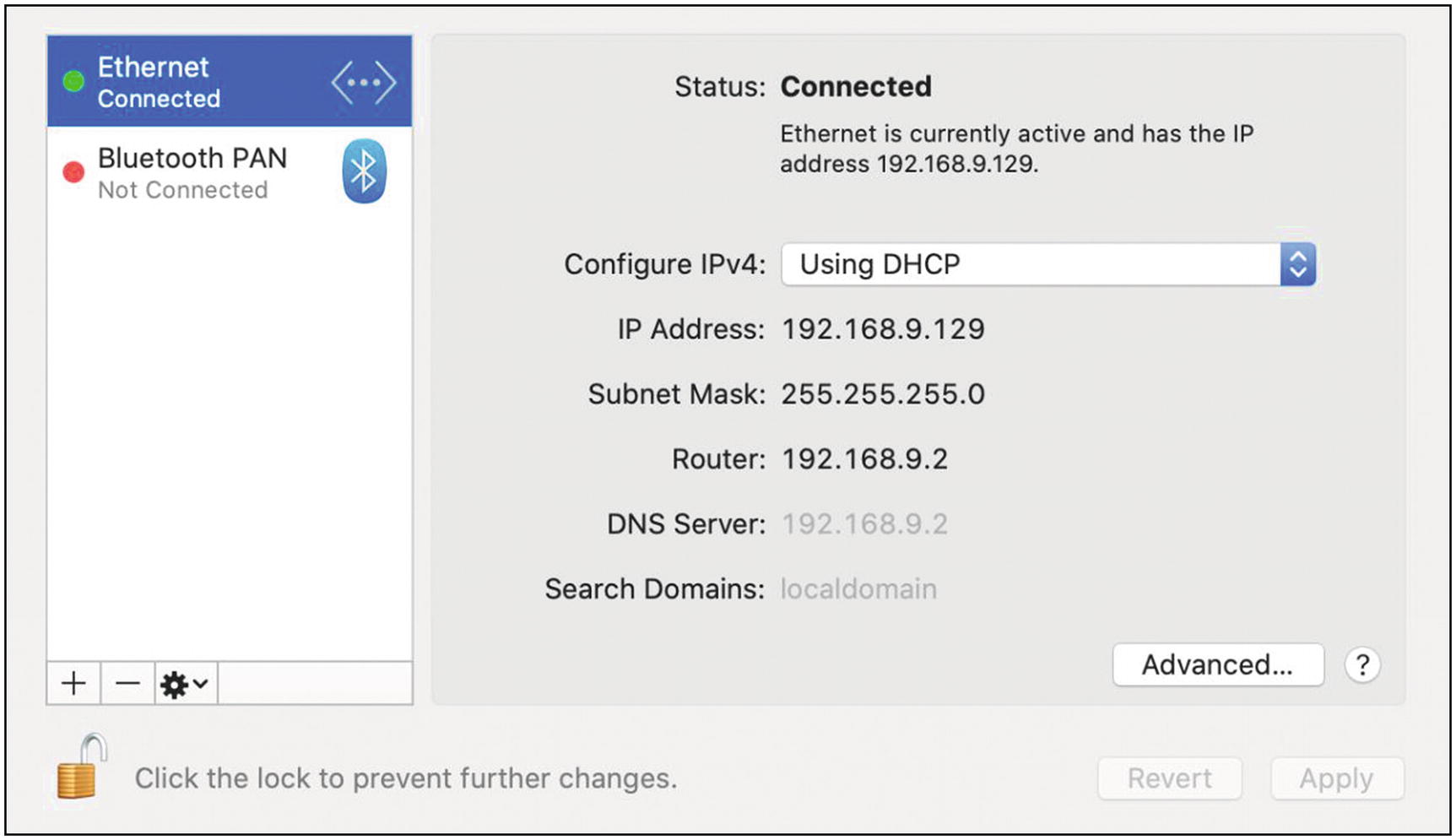

Tip 7-12b. Mac OS

- 1.

Open System Preferences from the Apple menu. Find Network and click it.

- 2.

If necessary, click the lock icon at the lower left and enter the admin username and password to unlock.

- 3.

You may see more than one connection here. You should probably change them all, but the primary one for laptops will be the Wi-Fi adapter. Repeat the following process for every one you want to change. Start by selecting the connection you want to change. Click the Advanced button at the lower right (Figure 7-26).

Mac OS network adapter settings

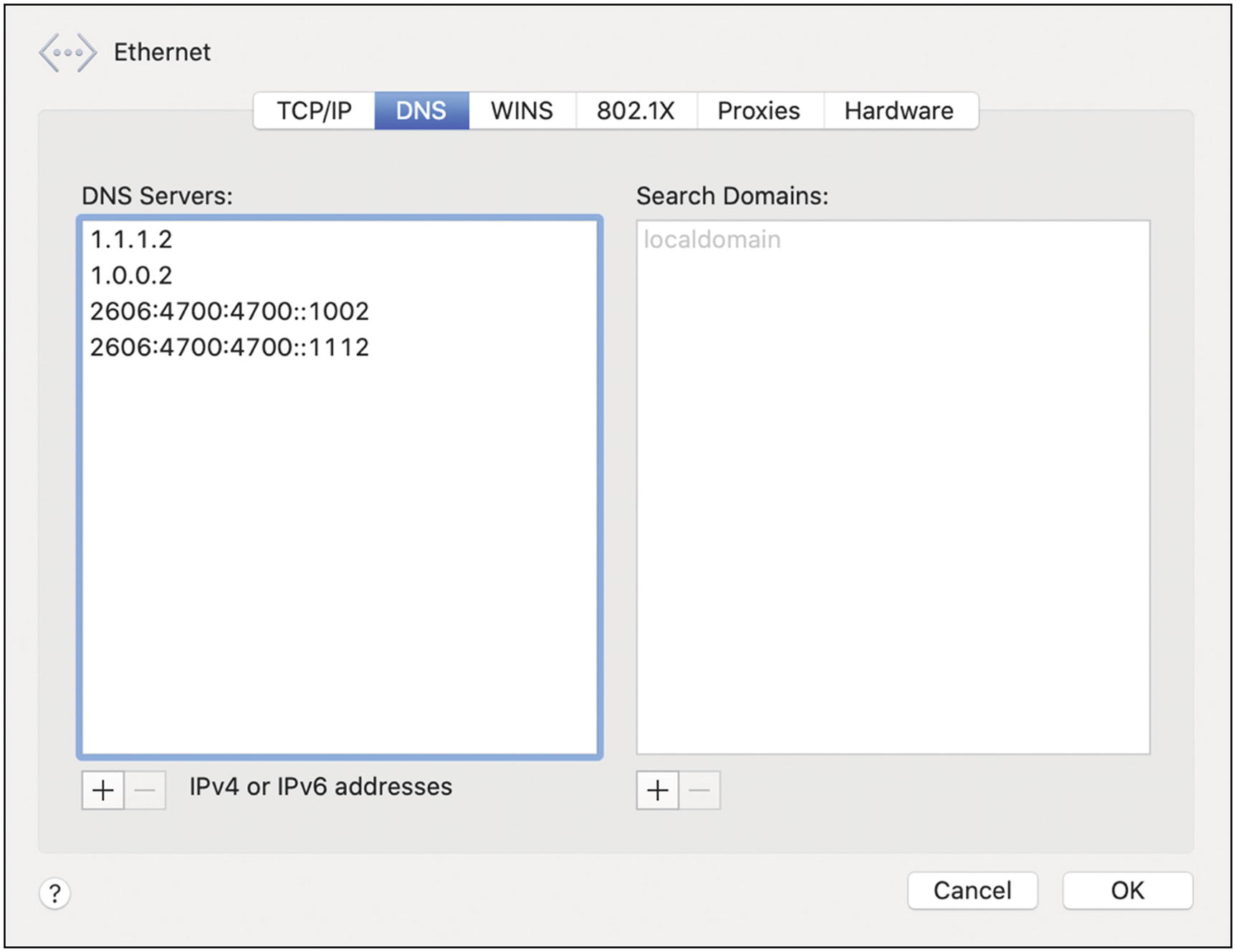

- 4.

Click the DNS tab. Change the existing DNS server by clicking the little minus button at the lower left. (Note that if these entries were set automatically by your network, you can’t directly remove them—they’ll disappear when you add the new ones using the plus button.) Add two more entries: the primary and backup DNS servers you want to use (see the previous tip for choices). You can add both the IPv4 and IPv6 addresses here. The following example shows the Cloudflare values (Figure 7-27).

Mac OS example DNS settings

- 5.

Click “OK” here and then “Apply” on the previous window.

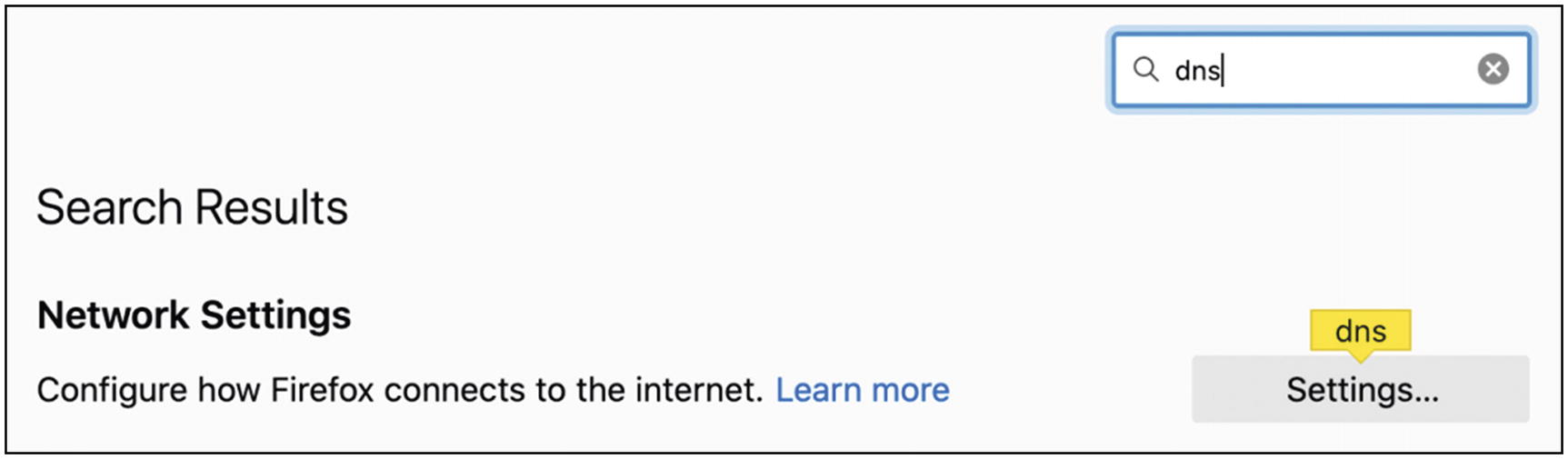

Tip 7-13. Use DNS Over HTTPS (DoH)

To truly make your DNS queries private, you need to encrypt them. There are a couple ways to do this, but the easiest and most popular one is to just send the DNS queries over HTTPS—the secure protocol we already use for our web surfing.

Firefox settings search for DNS

Firefox DNS over HTTPS setting

Mac OS and Windows are building support for DNS over HTTPS into the operating system itself, as well. You can look for these settings under the usual network preferences, when they become available. However, if your home Wi-Fi router supports DNS over HTTPS, enabling it there will cover all the devices in your home.