Trust is a most valuable currency within any organization, and in remote and distributed organizations, where coworkers and team members do not regularly interact face-to-face and may be geographically separated most or all of the time, it is crucial to success. In Chapter 4 we discussed the importance of hiring for trust. Now, we’re going to focus on how to build trust in remote scenarios. Going forward, everything I’ll cover assumes that you have hired with two-way trust in mind and are committed to developing and maintaining a culture of trust and accountability within your remote distributed organization.

Trust

Trust, along with its close partner Accountability, is the most basic currency in any organization. The confidence that exists when one person says, “I’ll take care of that thing” and others know that the thing will be taken care of is what enables any working relationship or team, on-site or distributed, to function. Trust is also the currency that enables people to have open and honest conversations and share enough of themselves so that others develop understanding of what makes them tick, and openly admit to mistakes and actively seek to address them and learn from them.

Trust is something that typically takes time to develop between people and groups. It is also extremely difficult to regain when lost or damaged. Leaders build trust by describing and embodying the type of positive environment they will foster, protecting teams, and following through on commitments. Leaders build trust by creating environments where mistakes aren’t punished – they are corrected and learned from.

People create trust through accountability and delivering on commitments. When a team shares a goal and everyone on the team does their part to meet the commitment, the team builds trust in each other. This trust in turn enables the team to extend their effort, knowing from experience that everyone on the team will do their best. When a coworker makes a mistake and turns to another for help and gets that help without criticism or judgment, trust is developed. When leaders hold themselves accountable and create an environment where accountability is expected and valued, trust grows.

In on-site scenarios, the factors that facilitate and create trust are supported by proximity and opportunities for social interactions that help build familiarity and knowing others. In remote environments, trust evolves in different and important ways. There are fewer non-work social opportunities, and so trust and accountability tend to be developed through delivery of work and follow-through on work and project-related commitments.

I’ve taught a master’s degree course on managing project teams for about 12 years. The original course and one of the texts we use was developed by my mentor, Dr. Ginger Levin. Dr. Levin and her writing partner, Parviz Rad, identified the obstacles to building trust on virtual teams in their 2003 book Achieving Project Management Success Using Virtual Teams. Their book sourced research going back to the mid-1990s regarding the challenges associated with building trust on virtual teams – this is not a new topic.

Rad and Levin describe trust as the key ingredient necessary in preventing the physical and structural separation between team members from manifesting as psychological distance. Rad and Levin further note that online interactions can preclude the multi-channel cues that make up full communications, resulting in lower-bandwidth scenarios for developing understandings of personalities and capabilities. Trust is listed as one of the key people attributes necessary for virtual project organizations to ascend to higher levels of maturity and competency. At the highest levels of maturity and competency, virtual team members share concerns, work approaches, and engage in collaborative leadership based on trust (Rad and Levin, 2003).

Collage.com – Examples for All of Us

Kevin Borders, co-founder of Collage.com, references the importance of trust as critical in remote environments. Borders notes that trust in remote scenarios starts with leaders and creating what he calls a “mistake-friendly culture.” When leaders admit mistakes and share challenges they are facing, it models for the whole organization. Borders describes how retrospectives help to create trust, and how the assumption of positive intent by all team members is critical. Leaders must be accountable and own those retrospective findings that could prevent future problems.

The importance of personal connections is a key part of the Collage.com approach to trust. By intentionally creating practices that encourage discussion of personal and family details and reinforcing these practices, managers stay connected to and develop empathy for their teams while people in different functional areas learn about their coworkers. Seeing others as people and not just coworkers is an important factor in building trust.

Reinforcement of shared objectives helps remote teams avoid or resolve disagreements – Borders notes that in remote environments people may engage less often, making the shared goal critical to enabling people to trust one another’s decisions. I have found this to be an important component of team meetings and all-hands meetings. I use these meetings as opportunities to reinforce our ongoing and consistent values and to remind groups and departments of the consistent “north stars” that we are striving to evolve and achieve.

Like many other all-remote organizations, the in-person all-hands is an important part of how Collage.com builds and maintains trust. These periodic in-person opportunities have proven essential to Collage.com, as they have for Automattic and countless other organizations. In addition to in-person leadership Q&A sessions and cross-department collaborations sessions, the after-hours social opportunities that occur at gatherings such as these are incredibly valuable to fostering and cementing relationships and trust that last long after the in-person gatherings are done (Borders, 2020).

Swift Trust

Have you ever joined a team of people you’d never met before to work on a task or a project, and found that you all gelled and began to get things done relatively quickly and with a minimum of concern as to who was in charge at the moment? One name for that experience is “swift trust.” This is the unspoken agreement that a group of like-minded and competent people quickly develop that enables them to assume the best of one another and focus on accomplishing work versus jockeying for leadership or worrying about who is doing the most or least work.

Swift trust can be more challenging to develop on virtual teams and in remote settings, but it can be achieved, and it is critical for success in these scenarios. Leveraging the initial atmosphere of assumed positive intentions, shared commitment, and benefit from the outcomes helps to foster swift trust and also helps to create experience on which to build more lasting forms of trust through the experiences described earlier.

Foundations and components of Swift Trust

Personality Types – How They Adapt

People approach and respond to remote work scenarios in different ways. No one who’s spent any time researching or working with the topic of people and personality types recommends slotting people into groups and generalizing their behaviors and tendencies. Yet, understanding these general frameworks and having conversations with the people in your organization to better understand their needs and responses to workplace configurations is a key element to establishing a successful remote and distributed organizational model.

Organizations operating in remote and distributed modes prior to 2020 already understood the importance of acknowledging and adapting to people’s personal styles and needs and had various methods for doing this in place.

Plenty of other organizations learned this for the first time during the Covid-19 pandemic. Organizations forced to move to a remote work model had an opportunity to learn how people responded to this scenario and to develop methods to support them and the varying needs that people with differing personality types and life situations have when working remote.

Introverts like to process and think – they tend to gather information, including information from interactions with others, and then seek some time and solitude to process and come up with ideas and solutions. Introverts often prefer to work alone for periods of time and find this to be productive. Most critically, introverts find that engaging with groups of people for long periods of time drains them of mental and physical energy, and after such engagements need time to recharge.

Extroverts like to talk through their ideas and form new thoughts and solutions through these interactions. The lively exchange of ideas helps form and improve their thinking, and the engagement with groups of people in these types of sessions energizes them. Extroverts desire interaction with others to maintain that energy level and engagement.

Extroverts may find the remote/virtual team experience generally unsatisfying – leaders must find ways to compensate. This could include frequent one-to-one check-ins, regular engagement in chat channels, engagement in small groups of others with similar needs, and activities such as book clubs and special interest groups.

Introverts may find the remote/virtual experience generally satisfying but could become disengaged – leaders must be alert to this and find ways to compensate. Given the many competing priorities that leaders face, it can be too easy to leave the introverted worker to their own devices, assuming that, based on what you know, he or she is okay with this.

It is useful to consider the variations in learning styles that become even more important in remote and distributed environments. With a totally on-premise workforce, it is easy to gather groups of employees together for training and learning. The employee learning and organizational development departments of organizations often rely on this type of training, combined with various types of online learning, in order to convey mandatory information or for training on things like soft skills.

In a remote distributed environment, there are multiple ways to convey similar information that can account for variations in personality types and learning styles. Extroverts who appreciate learning from a speaker or presenter can benefit from a live webinar. Others who may prefer not to be present in the live webinar can watch the recordings. Everyone can take part in asynchronous online learning through various learning systems.

As a professor with over 20 years of working with adult learners in executive and graduate programs, I believe that professionals are responsible for identifying their learning needs and objectives and making these needs known to their instructors or employers, while also being accountable for ensuring their learning needs and objectives are met. Remote and distributed organizations can offer a variety of ways for the adult learner and worker to get their learning needs and objectives met.

In summary – people with different personalities approach and respond to remote work scenarios in different ways, with extroverts potentially finding it an unsatisfactory experience and introverts being totally happy with it. The key is for leaders to recognize these qualities in people and teams and find ways to adjust. Recognize that the extroverts may be craving a chance to be in the office whereas the introverts are perfectly happy with extended periods of no on-site/in-person time, but run the risk of becoming disengaged. Learning and organizational development efforts must also account for personality types and learning styles, and the remote distributed organization benefits from a variety of ways to approach this.

Motivation – Theory and Practice

In a course that I teach on leading project teams, we spend an entire unit on motivation. It’s an important topic and a key leadership skill to have and to foster in any work environment, and in remote and distributed scenarios it is critically important. As with personality types, there are a myriad of theories and approaches to motivation, and one could devote an entire book to them – but not here. For the purposes of this section, I’ll nod to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs but spend most time covering some basics of Motivation-Hygiene Theory as well as Theory X and Y management and how these two approaches have applicability in remote and distributed settings.

Maslow’s Hierarchy

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

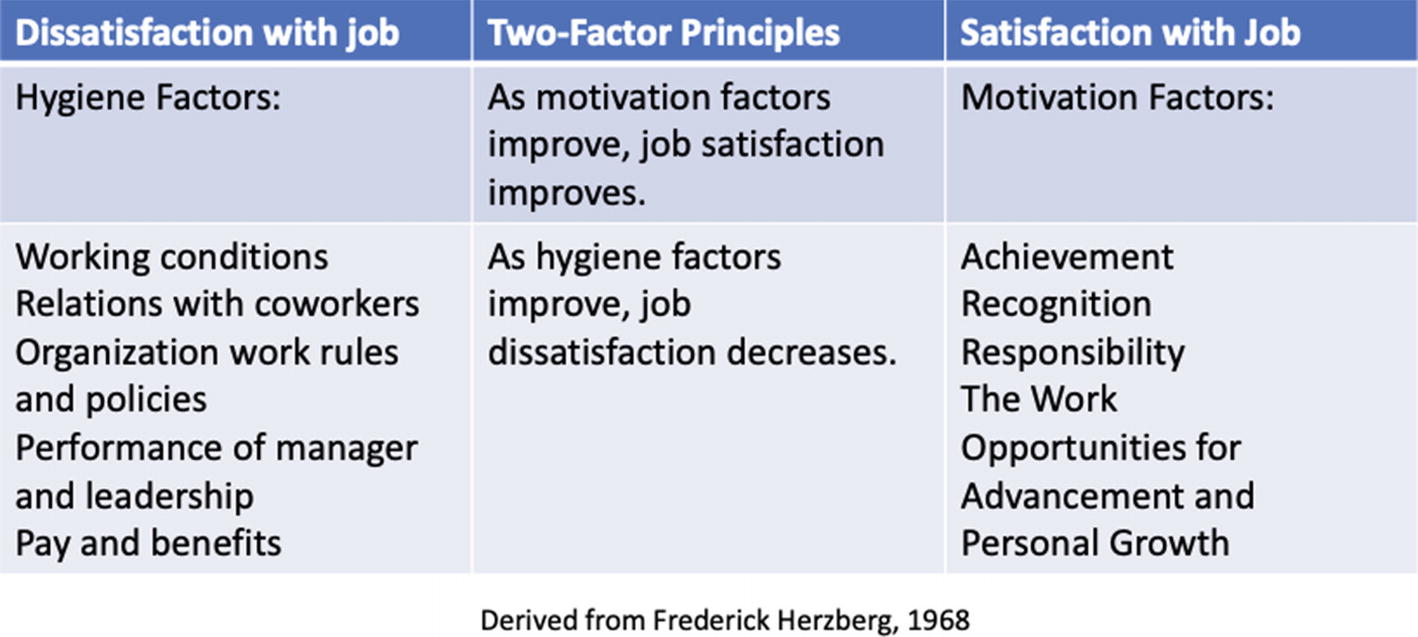

Motivation-Hygiene Theory

Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene Theory (Derived from Abraham Maslow, 1943, 1954)

Motivation-Hygiene theory is important to remote and distributed work scenarios because elements from both categories will influence the creation and evolution of culture and practices and are within the sphere of leaders to tune and improve. Aside from salary, the leadership culture and style, policies and practices and the accommodations and support systems for remote workers are critical hygiene factors to consider in building or evolving a remote distributed environment.

The implication for leaders and organizations is this: Creating remote and distributed work environments that foster trust, that have flexible rules and policies, that facilitate positive relationships with coworkers and assume the presence of accountable and knowledgeable leaders will have as much of an influence on the success of your remote distributed organization as pay and benefits, assuming that these are competitive for your vertical or industry.

EDL Consulting and the culture created by Bill Loumpouridis is a perfect example. As consultants in a specialized field of software development and ecommerce, EDL employees were well-compensated and got their pick of the best possible technology with which to do their jobs. We had reasonably cool swag as well. However, similar boutique consulting firms sometimes offered higher compensation. People who left EDL to work for the competition often found that the culture was not as conducive and supportive of remote work and their career growth as the culture that Bill created at EDL. Not only were the hygiene factors present at EDL, but EDL provided opportunities for achievement, recognition, growth and advancement, and challenging, cutting edge work in our particular field of ecommerce and software as a service on the Salesforce platform.

Theory X and Theory Y

Theory X: These managers generally believe that people don’t want to work and therefore need to be managed and motivated through rewards for working and punishments for not working. The classic micromanager fits in the Theory X category, and organizations built around this approach tend to be hierarchical with lots of management layers to provide supervision and hold everyone accountable. This is also the approach of the manager who does not trust people unless they can see them and thinks that butts in seats equals work and accountability.

Theory Y: These managers generally believe that people like work – that work is a natural and productive part of the human condition and therefore people find satisfaction and self-expression in working. Theory Y assumes self-motivation, ownership, and responsibility, and therefore typically a flatter and more collaborative management style is present in these organizations. This approach is a natural fit for the remote distributed environment.

If you are a Theory X leader – ask yourself why this is the case. Seriously consider whether this approach and personal style is valid and effective in a 21st century knowledge and technology-oriented workplace. There are doubtless some fields and areas where reward and punishment and micromanagement are valid leadership approaches, but the scenarios in most remote work settings are not those and the Theory X approach will be destructive.

If your organization tends to Theory X – this is a critical and potentially limiting factor in the successful long-term adoption of remote and distributed models. Consider whether it is possible to transition the dominant leadership approach given the traits and styles of the most senior leaders, and the tenure in office (and possible attrition) of senior and mid-level managers who ascribe to this approach.

Theory Y leadership is in the DNA of most “from Day 1” remote distributed organizations. Founders tend to be highly motivated on their own, and their early hires mirror, by necessity, this approach and attitude. As they grow and scale, remote distributed organizations intentionally recruit and hire for, then foster and reward the Theory Y approach.

As you and your organization evaluate the adoption of remote distributed as a long-term organizational and working model, it is critical to evaluate the extent to which Theory Y leadership is present in your organization. The presence of Theory Y leadership and motivation is a critical factor in the success of this transition.

Overall, the remote distributed, virtual organization or team requires nuanced application of many of these motivation techniques and approaches. Because of cultural differences, it may be necessary to focus on individual motivation, since no single motivational approach would work culturally for the entire team. Similarly, it is important to consider cultural factors in motivation, because in some instances and cultures, rewarding the individual can be counterproductive – we will discuss this in a later chapter.

Motivation for virtual team members must also account for and address the potential feelings of isolation and disconnection some virtual team members may feel, depending on the circumstances. In cases where part of the team is colocated and part is virtual, the virtual team members may feel excluded or less valued due to the physical separation, and benefit from focused efforts to highlight their contributions to the team or project as well as aforementioned and intentional work by leadership to avoid this happening at all. I previously noted some research that supports tendencies by some managers to consider people who come into the office to work as more productive and higher performing than remote workers – be active and intentional in assuring this does not happen as you design and evolve your remote distributed organization.

This same issue may arise based on countries and cultures – if team members from a particular country or culture dominate the make-up or proceedings of the team, other members may feel less valued and require focused efforts to motivate them and show appreciation for their role and work.

Consider – as a leader, traveling to visit virtual team members, or consider conducting a virtual team meeting from various team member locations. This example sends a clear message to each virtual team member and the entire team that they are valued and important wherever they are and can be highly motivating.

Using In-Person Events to Build Connections

One thing I learned during my time leading remote software development teams at CloudCraze was that even though we were from inception a fully remote and distributed team, we needed to gather periodically to plan, brainstorm, and whiteboard, and also to build and grow our personal connections and keep our “esprit de corps” as a team. My experience and the experience of companies like Automattic, Collage.com, and countless others is that connections and team spirit are hard to maintain without the cadence of intentional on-site gatherings. The models for these gatherings share common elements, so I’ll give some examples from the CloudCraze on-sites I organized from 2015 to 2017 and add some additional examples from Automattic and Collage.com.

CloudCraze – November 2015

CloudCraze was acquired by a group of Chicago investors in August 2015. As part of the post-acquisition reorganization, I took over as vice-president of software development and support. One of my first moves was to organize an on-site all-hands meeting of the software development and support team that November. It would be the first time that the entire team had ever gathered together, and for many, the first time that they had met each other.

This meeting also coincided with the need to complete and release a version of our product that had been in progress all summer. The work had stalled due to the acquisition and due to the annual fall Salesforce conference in San Francisco, which tended to consume everyone’s energy. The gathering would be an opportunity to introduce myself as the new leader as well as introduce the new director of engineering who was promoted to this role as part of the re-org.

We gathered on a Monday, had a huge social outing at one of Chicago’s famous pizza joints, and started and renewed relationships over numerous adult beverages. Work sessions focused on structure and expectations of the newly formed unit along with presentations from other leaders. The final full day was consumed with the entire team gathered in a massive conference room testing and fixing final bugs before releasing the new version of the product.

This first meeting set the pattern for subsequent meetings. As we completed each release of the product – spring, summer, and fall – we planned an on-site gathering in Chicago. We started on Monday, with people arriving from all over the country, stopping in the Chicago office, and then attending a large and generally raucous social event that evening. Other leaders and people from other parts of the company often joined for the socializing.

Tuesdays were typically an all-hands discussion of the release we were completing. We brought in other parts of the organization such as professional services and sales and marketing to brief them on technical elements of the new product. We also performed a release retrospective, discussing practices that worked well and good decisions as well as things that did not go as well and decisions we would revisit for future releases.

In some of these meetings, we weaved in question-and-answer sessions with our C-level leadership, training on security and new platform features, and other activities that benefited from having the entire team present in-person.

One to two days were devoted to planning the next release. Reassessing the product road map, finalizing and committing to features, and planning the next month of work consumed the remainder of the on-site. Socializing after hours continued, with groups of people self-forming along with planned activities.

Examples – Automattic and Collage.com

Both of these organizations engage in similar all-hands gatherings a few times each year. Automattic tends to do theirs in different locations, while Collage.com does theirs twice a year in the same spot. Both organizations share the goals of in-person meetings – foster relationships, celebrate accomplishments, have fun as people as well as coworkers, and also accomplish some work-related stuff.

Both Automattic and Collage.com attest to the value of these on-site/in-person gatherings, including the after-hours socializing that occurs, as valuable and important to building relationships and enabling their success during the majority of time that the organizations are in fully remote distributed operations. This reinforces both formal studies and practical notions that you tend to trust and look out for the interests of someone you have met, shared a meal or a beverage with – even better, someone with whom you have created a unique and positive memory with – which further supports the importance of these periodic in-person gatherings.

Adopting the Practice

If you are building or transitioning to a remote and distributed scenario, I highly encourage that you plan for similar practices as those described here. The intentional gathering of an entire team or entire organization at least once and ideally a few times each year is a proven and effective way to build and enhance the relationships that are foundational to trust, productivity, motivation, and overall satisfaction. The time, resources, and money spent doing these and ensuring they are fun and memorable experiences will prove to be valuable investments.

Think about your culture and the overall personality of your organization. There are doubtless elements of your particular organization or line of work that will influence how these on-site gatherings can go. You may have specific work rules or even regulations that determine, for example, whether adult beverages can be part of the equation, and what you can spend and how. Regardless, take the time to think these through and make sure that these in-person gatherings of teams and organizations happen. They build the bonds that enable trust, empathy and effective remote work teams.

The Best of Both Worlds

Remote and distributed scenarios are not an all or nothing proposition. Perspectives that state that all work and organizations will go remote or that state that there is no substitute for in-person work are absolutes and will not be realized. You can have it both ways, and your people can, too. In fact, it is likely that your model for remote and distributed work will include time in the office and time remote each week or each month for most of your team.

Earlier in this chapter, I wrote a bit about introverts, extroverts, and motivation. These elements are unique in each person and influence the degree to which people want or need to be around others as well as work independently. As well, work/life situations will afford opportunities to work from the office on some days, home on others, and the favorite coffee shop or the library on still others.

Assume Hybrid

We like hybrids. Hybrids enable us to have our cake, and eat it, too. Or enjoy two flavors of ice cream at the same time. Or the economy of an electric motor with the power and range of an internal combustion engine. Or cloud-based and on-premise IT systems. You get my point. As you consider models for remote distributed work, your most likely scenario is the hybrid where people spend some time in the office and some time working from somewhere else in any given period of time.

Creating the expectation where a mix of on-site and remote work is the norm is the most realistic and optimal way to go after so many have had the opportunity to experience remote and distributed environments. People will want to have it both ways – they’re going to want to spend some time on-site and they’re going to want to have the flexibility of remote work. This arrangement provides opportunities for people to determine their own needs for contact and social working – encounters that foster relationships and build trust, which sustain them when they are working remotely and distributed.

As a leader and as an organization, it is critical to foster and enable that flexibility, and build practices and systems that seamlessly support it. As a leader, it is important to consider those work scenarios that would be best served by having people present – and then challenge that. Ask yourself and your team – why? Is the interest in having people gather in-person based on habit or a bias? Or are there practical reasons to do so? The best thing a leader can do is figure out what “hybrid” looks like for their particular situation, articulate a vision, and do your best to make it so.

Four Generations in the Workplace – Differing Expectations

Another thing to keep in mind – we have four generations in the workplace, and there are pretty broad interpretations of what constitutes “work” as well as levels of experience with technology. Older generations may be wedded to the “nine to five” model, while younger generations are already accustomed to different hours and different models of “in the office” versus remote and distributed scenarios. As leaders we need to accommodate and, in some cases, coach others through this.

Potential case in point: You may need to mediate and coach in scenarios where older workers, used to being in the office during set hours and potentially less comfortable with the technology and tools that enable remote meetings and collaboration disagree with a project schedule or collaboration approach proposed by younger team members who are comfortable with remote, flexible scheduling around work/life balance, and the tools and tech that enable this.

It is critical to keep in mind that each generation's perspective has value – no one here is right or wrong. As you build the remote distributed culture of your organization and determine where you need policy, keep in mind the needs and perspectives of each of these cohorts and plan to be flexible and iterative. You will doubtless learn as you gain experience and work through various scenarios.

Summary

This chapter focused on people and various aspects of human behavior, expectations, and motivation in remote and distributed scenarios. We discussed the importance of trust and how it is developed, and we looked at the importance of leadership attitudes and approaches to motivation. We discussed how to leverage on-site gatherings to build and enhance relationships, and how the likely model for most organizations will be a hybrid mix of on-site and remote work, where people spend days in the office and work elsewhere during the week for a variety of reasons and benefits.

In the next chapter we will focus on best practices and tools that ensure remote and distributed organizations operate effectively and create the best possible experience for everyone.