In the simplest possible terms, cyber threat intelligence (CTI) is the process of taking disparate pieces of information about a cyber attack and identifying the context in which it happened and what that means. It is the same process a traditional intelligence analyst working for the military or law enforcement would apply to an investigation; it just sits within the realms of cybersecurity.

The earliest example of CTI, at least in terms of prominent media coverage, is probably the Mandiant APT1 report issued in 2013. This report was an in-depth, highly detailed insight into the cyber operations run by part of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in China. The report went as far as identifying the individuals involved, the buildings they were working in, and even so far as to individuals’ home addresses. It was an incredible read, and for me, that report was the moment CTI became an industry in its own right. Before the APT1 report, CTI was not well regarded, nor was it widely practiced. That report changed everything. People realized they could finally talk about this kind of thing in the public domain. As technology has improved and become more widespread, the amount of data accessible to a “normal” person started to match those available to the super spies in GCHQ or the NSA. It truly was a watershed moment for the industry.

Following APT1, several companies started to sprout up and offer their “highly detailed” CTI products. Some of them were groundbreaking for their time, but as the world has moved on, the companies haven’t. It’s a common issue as alluded to in the previous chapter. The best CTI vendors as I write this have evolved a long way from being able to scrape web pages automatically. The trend in the industry is moving away from being focused on IOCs (indicators of compromise) and moving toward the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used by adversaries. What I mean by that is rather than continually being fed a list of domain names, IP addresses, email addresses, etc. – some of which will definitely be malicious – a large number will be false positive. With TTP-level detection, we start to look at the actual processes and methods used by the villains to identify and prevent them from successfully gaining entry into our networks.

This approach is a much more significant technical challenge, of course, and it relies on having the technology, detections, and staff capable of identifying and responding as necessary. However, it provides you with a much greater level of response. For example, you might identify a phishing campaign from a threat actor that contains fraudulent invoices; you find the email addresses used, the domains used in the email, and how they register them so that you can track them in real time. You can continually update your blocklists, and everything’s great. But that’s only one campaign, from one actor. What happens when a different actor does the same thing? They might use another registrar or hosting provider; they might use an additional email service to send the emails. As a result, you might miss this new campaign, and thus you may find they gain a foothold and achieve their aims before you’ve had a chance to respond.

If we take this example and apply our response at the TTP level, we’re much more likely to identify and block the adversary before they have any chance of success. If we understand how invoices from our suppliers look, how their emails are structured, and what the documents look like, we can put mitigations in place to identify fraudulent emails as such and mark them as spam etc. It wouldn’t be 100% guaranteed to be successful, of course. But if your supply chain were to be compromised, there’s a chance that a legitimate-looking email would get through. Still, it does mean that you’re much less likely to find emails coming through and being acted on across the broader range of actors than you would by responding directly to the IOCs alone. It might be a bad example, but I think the concept rings true. Taking a more holistic approach, you can focus a lot more on prevention than response, and that has to be a good thing.

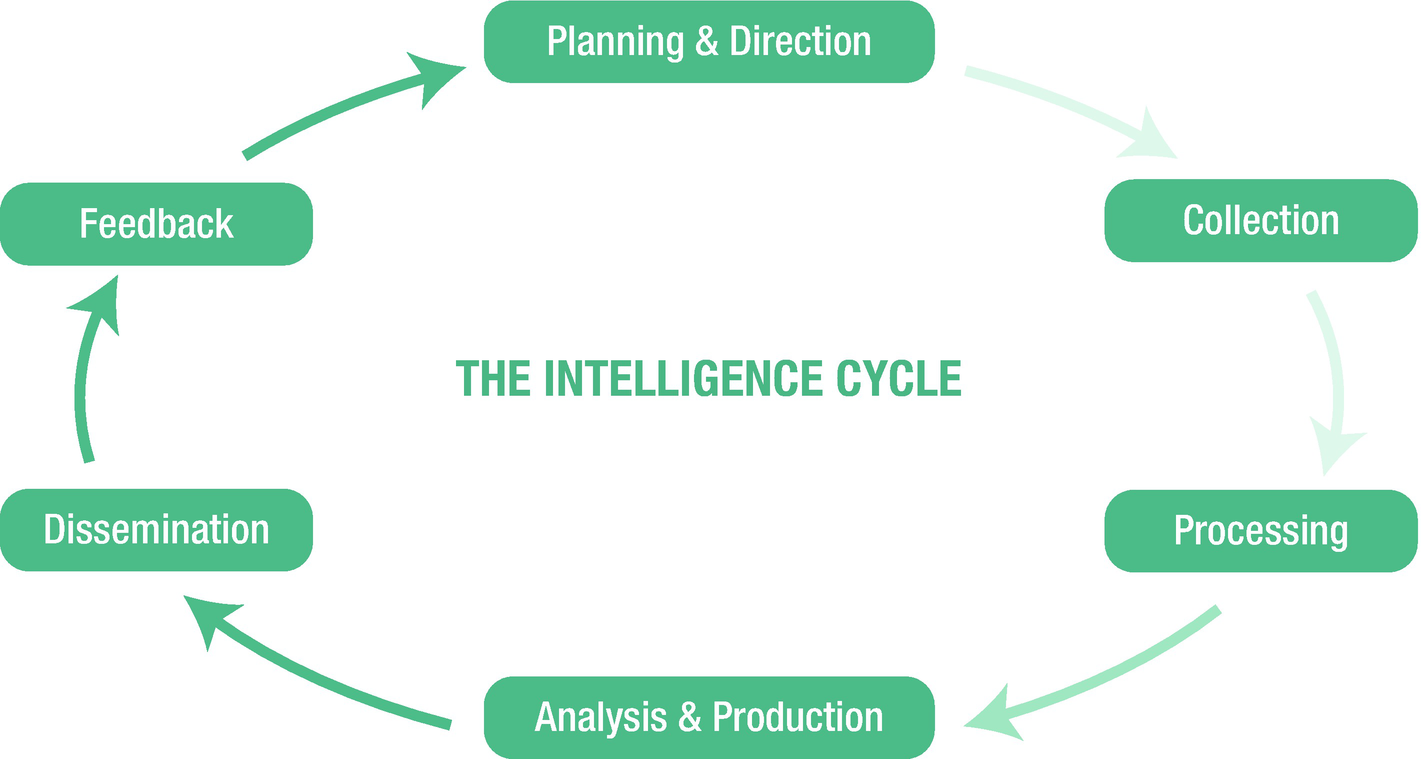

The Intelligence Cycle

The intelligence cycle is the process an analyst uses to collect, analyze, and report intelligence findings. The cycle is the same whether the analyst is looking at SIGINT, HUMINT, cyber, or imagery-based intelligence. The path is always the same, and when the process ends, the analyst starts again with the next requirement. Let’s break down each step of the intelligence cycle and explain what happens at each point.

1. Planning and Direction

As discussed in Chapter 1, this is where the intelligence team prioritizes their intelligence requirements. If we assume that the tools in place are implemented, and we’re purely considering the analytical process, this is where the requirements about specific topics or themes are established.

For example, the UK government deems terrorism a highest-priority threat. The UK intelligence agencies then put resources and tools in place to meet this requirement. In cyber, you’ll probably consider the danger from Business Email Compromise (BEC) fraud to be one of the largest threats to your business. You instruct your intelligence team to monitor for threats relating to your organization and to stay on top of trends in phishing emails that could be used to target you.

The intel team takes this requirement, establishes which tools and sources would be best placed to fulfill it, and then sets about establishing their collection for this particular area of concern.

2. Collection

With the requirement established, the focus shifts to collecting relevant intelligence. An analyst will use the commercial vendors to monitor for threats and set up monitoring or alerts, will look through the existing intelligence repository (if you have one), and should also monitor open/closed source to aid in their investigation.

This process can take considerable amounts of time, dependent on what the analyst identifies and where the trail leads them. This is a good sign – it means you’re bringing in good data, and you’re finding potentially key pieces of intelligence that could prevent your business from suffering a major incident. However, that’s not to say that a short investigation is a negative sign either.

Dependent on the requirement, you may find there’s very little information regarding your business or this particular threat at the time the investigation occurs. This is why the cycle repeats; just because you don’t find anything today doesn’t mean that you won’t find a significant amount of information in the future should you approach the same issue. Your team should be mindful of the technologies they’re using and how much value they are getting from them though. If you’re spending a lot of money on a tool that does not help you meet your requirements, you should consider replacing it.

When the analyst has exhausted their search, they should then begin the processing and exploitation phase of the cycle.

3. Processing and Exploitation

Traditionally , this part is where the translation of foreign languages happens. In CTI, this is where we bring all the disparate information into one place to enable the analysis.

Depending on the size and type of your organization, you might consider using a Threat Intelligence Platform (TIP) for this. TIPs are a potent tool for an analyst. A good TIP will act as an intelligence repository of all collected information, will identify links between disparate pieces of data from multiple sources, and will allow the analyst to automate large parts of the processing and exploitation part of the process.

If your team doesn’t have a TIP in place, this can be quite a laborious and manual process. There are tools available that can help with the link analysis of data (Maltego or i2 Analyst’s Notebook is an obvious example). Still, dependent on the amount of data the analyst has, they might have to rely on spreadsheets to record and track information. Not very cyber, I’m sure you’ll agree. However, once the processing of data has occurred, which can include de-duplication of data and checking for false positives or circular reporting, the analyst moves on to the analysis phase of the cycle.

4. Analysis

This one should be fairly self-explanatory. This phase is where the analyst brings all the collected and processed information into one place and analyzes it for new or key information that can provide context on the threat facing your business. They will look for patterns in data. For example, does a cyber actor use the same details for registering domains for their phishing campaigns? Is there a common theme or pattern in how they conduct their attacks? If so, how can we track or mitigate against it?

During this phase, the analyst may take a step back and look to start the collection and processing phases again, depending on what information they have gathered. This might be the use of enrichment sources (e.g., using passive DNS tools to look for other domains registered by the actor they’re tracking), or they might have a new angle to investigate further based on the results of their initial search. This process can repeat as often as necessary until the analyst is content that they have all the relevant data and information needed.

Once the analyst has completed this phase, they will typically double-check again for false positives, before moving on to the dissemination phase of the cycle.

5. Dissemination

This phase is where the analyst takes all the new information they have identified and applies the relevant context for their customer into a finished intelligence report. This finished report can come in many forms: for example, a long-form written report highlighting the trends, key TTPs, and motivations of the actor in question. It could be a slide deck intended for consumption by senior board members or a machine-to-machine report which includes the relationship information between different entities for ingestion into SIEM or other security platforms.

The type of report that is required will usually be set at the outset of the cycle. Depending on where the requirement came from and who the audience receiving the report is, deep technical analysis is unlikely to be shared with C-suite readers. However, a high-level global trend report on the threats from cybercrime probably would be. Of course, this can change depending on the organization and the nature of its business. Once the report is disseminated, or the analyst provides a brief, arguably the most important (and least implemented) part of the process occurs, feedback.

6. Feedback

As with anything that’s customer-facing, intelligence analysts have the same problems as anyone else: getting feedback from their customers.

A good CISO and good security team will provide constructive feedback on the products published by the intelligence team and the results of implementing any actions. This is vital for the intel team, so they know what products are hitting the mark and which ones don’t match their customers’ requirements.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the intel team lives and dies by the quality of their requirements. If they have a very flimsy set of criteria to meet, you’re unlikely to reap the full benefit of having an intelligence team. If the requirements are directed and clear and the team receives regular feedback on their products, you are infinitely more likely to see the value they provide. That’s the kind of value you can’t just see from buying Shiny Super Security 5000 for £78bn.

The intelligence cycle

The Diamond Model

Adversary

Victim

Infrastruczture

Capabilities

The Diamond Model

The point of the diamond model is to allow an analyst to build out a picture of a cyber attack and to identify links or aspects for further investigation. By understanding this model, an analyst can quite quickly map out what happened and will be able to provide a useful output to their SOC or management team. This will help to drive mitigation or build understanding around the incident. Let’s look at each of the points in turn and how they relate to each other.

Diamond Model – Adversary

The adversary point of the diamond focuses as you’d expect on the threat actor behind the attack. The first piece of information you’ll normally have for the adversary is their initial entry point into your network. This is likely to be an email address from a phishing email or the IP address of the remote connection used to exploit a vulnerability or access an unsecured part ovf the network.

From this initial piece of information, the analyst will conduct their own research to find more contextual evidence to help understand what the actors’ motives were or the scale of the risk to the organization. Each piece of information is collected and processed to help them with the analysis phase of the intelligence cycle and, ideally, help them to attribute the attack. Although it’s unlikely you’ll attribute a cyber attack to a specific threat actor, you should be able to at least identify if the threat looks like low-level cybercrime, advanced cybercrime, or potentially APT/nation-state actor. Don’t worry about this, attribution is incredibly difficult at the best of times, and you need access to intelligence from more than one incident to really do it successfully. A large number of reports that attribute cyber attacks usually originate from organizations that deploy endpoint protection and thus have visibility across thousands of clients globally.

Once you have collected the relevant information on the adversary, the analysis can begin. In terms of the diamond model, this means grouping the relevant information along the right side of the diamond. For the adversary, the connections are infrastructure and TTP/capabilities. Where you find information relevant to the infrastructure used in the attack, you place it on that side, and likewise for the TTP/capabilities.

Diamond Model – Victim

At the opposite end of the diamond to the adversary is the victim. This of course represents the victim of the cyber attack and could be an individual, group of individuals, a whole organization, etc. The aim here is to build out what was affected and other relevant information that could help provide key context to why the attack happened. Is the victim supportive of controversial political policies? Are they supportive of an agenda that goes against a particular nation or set of nations? What sectors do they operate in? Are they cash rich and thus susceptible to cybercrime? These are just a couple of examples of the questions an analyst should be asking when considering the victim in the attack.

For technical analysis, the analyst should be looking at the entry point for the cyber attack. In the example of a phishing email, they should be asking if the email recipient has been seen in previous data breaches. Is the individual who received the email a public-facing employee? Do they advertise their level of access on LinkedIn accidentally? Is the email they received specifically crafted (spearphishing) for them, or is it a lot more generic (traditional phishing) and therefore more opportunistic? This is a vital step in considering the scope of the incident. If the individual received an email that all other things being equal appears to be completely legitimate, then you clearly know this is a highly targeted attack, and thus your level of response is likely to increase. If the employee clicked a link in an obvious fraudulent email, then they may need some training to help them understand the risk in future, but once mitigated you unlikely make any sweeping changes.

The victim aspect is possibly the most important point of the diamond for understanding the why behind a cyber attack. Once you build out this picture of the victim and you consider the reasons why, it helps to understand the adversary better and subsequently the infrastructure and TTPs. It also allows an organization to understand the level of response it may need to mitigate any ill effects from the incident itself.

Diamond Model – Infrastructure

The threat actor used [email protected] as the email address for their spearphishing email to Bob.

The badguy.com domain is hosted by Villain Hosting Services in Russia, determined by the analyst after conducting a WHOIS lookup on the domain.

A bit of research reveals that Villain Hosting Services is a notorious hosting provider. It has a history of providing hosting to sites selling and hosting illegal material on both the clear web (normal Internet to you and me) and the dark web (where villains and conspiracy theorists hide, also CTI professionals…).

Further research shows that badguy.com has been seen previously spreading malware that exploits a vulnerability in Microsoft Word.

Bob works for ACME, and they use Outlook for their corporate email. When Bob received a phishing email and opened the attachment, the Word document asked him to run a macro, which he duly did.

This macro exploited the vulnerable software, as ACME is naughty and didn’t patch its systems properly, if indeed at all.

The threat actor now has access to Bob’s machine, where he downloads further malicious software as part of a script that runs when the macro is allowed. This results in Bob’s computer becoming infected with ransomware.

ACME goes out of business because the ransomware spreads, and they can’t afford to recover the data or pay the ransom.

The last point is, of course, an exaggeration. Still, I hope this flow helps you to understand why this method is incredibly useful to an analyst and how it helps to inform the mitigation process.

From the victim side, by understanding the affected infrastructure, we can look at what the likely methods for intrusion are. This can range from particular types of malware, known exploits, or misconfigured containers, among others. Having this detail to hand will primarily help an organization to respond quickly and efficiently. You can also consider whether there is a risk of broader infection if the infrastructure is part of a more extensive network or in its own segregation. These things are vital to ensuring an appropriate level of response and to help reduce the risk of the same thing happening again and again.

Diamond Model – Capabilities/TTPs

This last point of the diamond is often one of the hardest to identify. The goal here is to identify the approach the adversary has taken and what steps they took to reach their goal. It also relates to how they “exploit” the victim. In our example, we would say spearphishing. However, there could be any number of steps used by the attacker to encourage the victim to fall for their bait.

This is the hardest aspect in my opinion as a lot of the time the intel analyst has to make a number of assumptions to fill in the gaps. This is because often you won’t have all the information you need to build out the diamond. That being said, you can gradually expand outward from the initial information you have, with the hope/expectation that as you build further outward, you understand more context, and you identify more of the actor’s TTPs and the capabilities they deploy. You may find this information from other threat reports about previous incidents or from intelligence you already have from your commercial sources.

If your intelligence team is able to understand the TTPs used by an actor and the tools/capabilities used, you can start to plan to block this activity at the TTP level rather than playing whack-a-mole with new IOCs as they appear. This is currently the gold standard for CTI practice; bear in mind there are very few organizations that are mature enough to implement this level of response currently, but I hope that this will improve over the next few years, as CTI garners more attention and focus from the decision-makers. That’s not to say that blocking IOCs is bad practice, far from it. IOCs still hold significant relevance for analysts and should be blocked appropriately.

However, once you understand that an actor can always change their infrastructure, register a new domain, or use a different email address, you can see that this isn’t a scalable solution. But human nature is to rely on the things we know and trust; therefore, changing behaviors is hard. It is the same for threat actors. By blocking their activity at a TTP level, you make life infinitely more difficult for them as they will have to adopt and create a new approach, something which takes them out of their comfort zone.

As you may expect, you’re also raising the bar to entry for all would-be attackers into your organization. For me, this is why TTP-level blocking is currently the aim and should be for all organizations. I am sure in time we’ll have to create and block even more advanced TTPs, but the positive sign here is that by always raising our own standards, we force the enemy to raise theirs. Making life a lot harder for them and reducing the chance of them seeing us as an easy target.

How Do We Apply Intelligence to Existing Security? The Cyber Kill-Chain and MITRE ATT&CK Framework

Understanding how we can apply the ideas and techniques discussed in this chapter to existing security frameworks or policies is arguably the most crucial part of any threat intelligence capability. If you have these great ideas and ways of tracking adversary activity and no way of applying them to your business – what’s the point?

Most security vendors nowadays will mention how they integrate the MITRE ATT&CK2 framework into their tooling and how this can help you. While they’re not wrong (it definitely can and should be helping!), too often there’s a breakdown between the SOC and TI team, or your existing way of working is based on detecting and remediating IOCs. This is a fine approach if it’s 2014, but I write this in 2020, and the world has moved on. The goal of any CTI program today should be to provide their business TTP-level detection and threat response.

This approach is hard of course, and that’s probably why a lot of companies have shied away from the idea. However, utilizing the (expanded) cyber kill-chain or the ATT&CK framework (ideally the latter), you can make significant strides in improving your detection. Let’s look at the reasons why this is important.

Human Behavior Doesn’t Change

Very simply, most people struggle to change how they do anything in life. Cybercriminals, APT groups, and people with ten heads who are omnipotent do too. We can play IOC whack-a-mole all day, every day, and sometimes we’ll stop an actor; sometimes we’ll be late. However, this will be a perpetual cycle you will struggle to get out of.

It is trivial to set up a new web domain to host malicious content or use as a Command and Control (C2) server . Criminals know this, you know this, and that’s why there’s a metric ton of open source feeds and resources that will tell you what the latest detected IOCs are and what they could be. Don’t get me wrong, this is important work, and you should be ingesting and blocking IOCs as relevant to you and your organization. However, a lot of SIEM tools will get increasingly more expensive the more data you’re putting into them. Probably not ideal if you’re a for-profit company or don’t have unlimited resources.

So enter the idea of TTP detection. Very simply, it’s significantly harder to change malware behavior and identify new exploits than it is to swap out the C2, hosting IP or domain name. Therefore, if you can identify the type of activity that a particular actor or malware performs, and you understand how to remediate against that, you can make the bar to entry much higher for any malicious actor. Apply this to an example of a targeted attack. Your CEO receives a highly targeted, sophisticated phishing email and falls for it. They open a document loaded with malware and subsequently get data stolen and their credentials harvested. However, your TI team tracks this particular actor as they target your sector. Subsequently, they understand that the malware used performs specific actions, and they have written remediations to block that activity at the point they occur. This action prevents the attack from being successful and saves the company from potentially significant financial loss and reputational damage.

For the threat actor, they’ll of course know the attack wasn’t successful, and if they want to target the organization further, they need to change what they’re doing and hope that their new approach avoids protection. Or, they’ll move on to a different target that they hope will be an easier target. I think it’s fair to say that the latter option would be easier and much more likely to be taken by any actor motivated by financial gain. A sophisticated APT actor may indeed change their approach or develop bespoke capability, but if you accept that this can and probably will happen if you’re in the kinds of business these groups operate against, then you can at least prevent lower-level groups from being successful.

This idea is not a pipe dream. It’s aspirational in a lot of CTI practices for sure; however, any good CISO should be aiming for this kind of detection and response from an intelligence-led cybersecurity practice. Trying to get a person to change their behavior is a lot harder than opting for the easy path. Criminals are no different, and this approach will serve you and your business well.

The IOC Is Dead. Long Live the IOC

The trusty IOC. The benchmark by which all over intelligence feeds are judged. This has quickly become an antiquated approach. The rapid year-on-year growth of cybercrime and the ever-expanding number of successful data breaches and cyber attacks show that there are more IOCs out in the wild than any team can realistically handle, manage, and block. It’s a simple truth. When you can ingest hundreds of millions of indicators, you’re not going to have the resource to analyze them all, and the fact is a lot of them won’t be relevant for your organization.

So why bother? IOCs are and can be very useful for identifying campaigns or trends and can be used to follow actor activity. Analysis of the indicators can provide the TTPs the malware uses to infiltrate a network, and they are quantifiable. You can confidently state how many IOCs have been added for blocking, and execs love numbers. You can’t really do that with TTPs in the same way. IOC remediation and blocking should be one of the things that your security team automates as they get more mature and have better understanding of the tools they have and the threat landscape that faces your organization.

But that doesn’t help with TTP-level detection, and most TIPs are so overly focused on IOCs that it feels like this is still the best way forward. Although I stated how useful IOCs can and should be, the fact remains that there are more attacks than anyone knows what to do with, and whack-a-mole is only reasonable to a point. Eventually, you will miss something, or a different actor will be successful. You must be ready to look at a deeper level to give yourself the best chance of avoiding successful compromise.

Security Products Are Evolving – So Should You

It should be evident that products are always evolving and changing, but a lot of security teams don’t develop in the same way. For every “Cyber Fusion Center” that stands up, there’s another siloed SOC that needs resourcing and people to realize that talking to each other solves a lot more problems than it brings. Really. Try talking to someone about something that’s their job that you don’t understand; you just might learn something! I know! I was skeptical too!

As more products come to the market or your existing tool upgrades and brings new features, you should be looking to capitalize on the changes in technology and the potential they have to help you. For every “Machine Learning, AI, Blockchain!”, there will be subtle additions that really do make the lives of all your security staff easier and enable them to work collaboratively among not only themselves but also the wider security industry.

The advent of the ATT&CK framework has accelerated massively since I first learned of it in late 2017. It’s evolved from a “useful way to track campaigns by specific actors” to the de facto industry standard for TTP tracking and monitoring. The MITRE organization has also started introducing more features or ways of using the framework for organizations, from adversary emulation (for penetration testing) through to adopting user feedback and suggestions for new techniques and removing redundant ones. As more providers include it as an “out-of-the-box” integration into their products, there are no reasons why your teams shouldn’t adapt and be using it. Almost overnight, you’ll be able to share intelligence or threat data with peers and the broader community in a way they can understand and interpret. ATT&CK allows for literal defense in depth, and who wouldn’t want that level of capability?

The Cyber Kill-Chain

It would only be right to mention the Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain. It was introduced millennia ago to track and understand the phases of cyber attacks, aligned to the more traditional kill-chain used by militaries all over the world.

- 1.

Reconnaissance – Indeed, this is the research and intelligence gathering phase for the target.

- 2.

Weaponization – Developing the relevant exploit for the target based on what the recon phase identified.

- 3.

Delivery – Obviously, the sending of the initial payload to the target, usually via email, USB drive, or web link.

- 4.

Exploitation – Once delivery is successful, the attacker will exploit vulnerabilities to execute code on the target’s network.

- 5.

Installation – Once code can be executed, the attacker can install further malware and malicious payloads, usually to target other systems or to help establish persistence on the network.

- 6.

Command and Control (C2) – Establishing the command channel for remote administration of the access that’s been established.

- 7.

Actions on objectives – The final stage where the attacker achieves their initial aims. This can be data exfiltration, executing ransomware, or establishing their next move.

The main issue from the original kill-chain is that cyber attacks can be and usually are more intricate than seven easy steps. It’s clearly little surprise that the ATT&CK framework and expanded kill-chain have more stages to them than the original.

I’ve included this section on kill-chain as, although it’s no longer as widely used as previously, it is still worth being familiar with as you may see the terms used in the industry, and you never know where they might appear. However, in 2020 the industry has moved away from the kill-chain, and ATT&CK is becoming the standard. This move to structured intelligence is also what we will discuss in the next chapter.

Key Takeaways

Intelligence is a long-term process. The intelligence cycle repeats and repeats; the more you do this, the more intelligence you gather and your process improves. It never stops.

CTI has methods which can be used to help the analysts to respond to incidents or remediate attacks, namely, the diamond model and the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

Adopting a TTP-level detection approach will assist in raising the bar to entry for lower-skilled threat actors. Human behavior doesn’t change, stop their TTPs, and most times you stop them.

The world of CTI is continually evolving, and so should you if you want to stay on top of the threats and attacks your organization will face moving forward.

IOCs are still worth following and blocking, but focusing purely on this will be detrimental to your security posture as the landscape evolves.