1

Hello, Kitchen!

Chapter Contents

Don’t Always Follow the Recipe

A Place for Everything and Everything in Its Place

WE GEEKS ARE FASCINATED BY HOW THINGS WORK, AND MOST OF US EAT, TOO.

Learning to cook can be one of the most rewarding endeavors of your life. Cooking—and eating—is a fascinating puzzle with many layers that, like those in an onion, peel away only to reveal another layer. No one is ever done learning to cook.

To the beginner, cooking has many hidden rules. Learning them is not so much about rote memorization as it is about curiosity, and that’s something geeks have plenty of. With time, the hidden rules of the kitchen reveal themselves to be a combination of art and science, giving you the keys to the kitchen kingdom. It is a worthwhile quest. With good food, you can take better care of yourself and your health. And with knowledge of the kitchen, you can cook and provide for others, building friendships and community.

This chapter is about the ground rules for the game of learning to cook—that tough outer layer of the onion, if you will. It covers how to approach the kitchen. What does it mean to think like a geek? What type of cook are you? Where do recipes come from and how do you interpret them successfully? What tools should you have in your kitchen? What else might be important in cooking? To answer these kinds of questions, you need to start thinking like a geek.

If you’re already comfortable in the kitchen, skim this chapter and dig right into the science of taste, smell, and flavor in Chapter 2.

How to Think Like a Geek

What does it mean to think like a geek in the kitchen?

In part, it’s technique and tools. Rolling pizza or pie dough to a uniform thickness can be hard, but slap a few rubber bands on each end of your rolling pin and you’ve got an instant autoleveling roller. Need to grill something, but don’t have a grill? Your oven’s broiler is extremely similar, but the heat comes from above, instead of from below. Spraying cooking oil onto a muffin tin? Open your dishwasher, set the tin on the opened door, and spray away—no messy counter to clean up, and the door will get cleaned on the next cycle.

Other times, thinking like a geek is about understanding why ingredients are being used. Following a recipe that uses white vinegar, but don’t have any? Lemon juice can work—if the recipe is using the ingredient as an acidifier and the taste won’t interfere. Making a dish that uses oregano for flavor, and you’re all out of it but do have thyme? The two herbs share common odor compounds and therefore are good substitutes for each other. Wondering if you can substitute baking soda for baking powder in a cake? Not without adding the right amount of an acidic ingredient to react with the baking soda.

Sometimes thinking like a geek means being inventive in how you solve a problem—coming up with a clever trick to get around something that’s broken or just seeing easier ways to do something. I know one person who tweeted, “My microwave has no 3 key, but I can enter 2:60.” Clever! Another friend uses a mug as a pastry bag holder—instead of trying to spoon stuff into a bag while holding it, she just drops it in a mug or pitcher and folds the top down around the edge. Learning to think like a geek is seeing the “why?” behind the technique or ingredient, and then answering that question in a useful way.

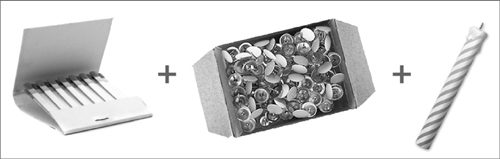

Here’s a thought experiment: imagine you’re given a candle, a book of matches, and a box of thumbtacks, and asked to mount the candle on a wall. Without burning down the house, how would you do it?

If you were stranded on a tropical island, how could you start a fire with a can of soda and a bar of chocolate? Think like a geek and see past the functional fixedness! Use the chocolate to polish the bottom of the can to a mirrorlike finish, then use the polished bottom as a parabolic reflector to focus sunlight onto a dry twig.

This experiment is called Duncker’s Candle Problem, after the German psychologist Karl Duncker, who studied the cognitive biases that we bring to problems. Things like the cardboard of the matchbook have a “fixed function” of protecting the matches. We don’t normally think of the matchbook cover as a piece of thick cardboard that’s been folded over; we just see it functioning to protect the matches. As a result, other uses of the cardboard become invisible to us.

We’re blinded by functional fixedness everywhere. Recognizing that an object is capable of serving other functions requires mental restructuring, whether it’s a rubber band on a rolling pin or lemon juice as an alternative acidifier. We see large wire mesh strainers as tools for straining pasta, but flipped upside down and placed on top of a frying pan, they work as splatter guards. Toaster ovens are perfectly serviceable for more than making toast: they heat air up to 350°F / 180°C, so why not poach fish in one if your oven is otherwise occupied?

Functional unfixedness: use a wire strainer as a splatter guard.

The obvious solutions to Duncker’s Candle Problem—pushing thumbtacks through the candle or melting the side of the candle so that it sticks to the wall—will either split the candle or set the wall on fire. The solution, at least the one Duncker was looking for, involves realizing that you have a box: the one that is holding the thumbtacks. Pin the box to the wall, stand the candle in the box, and light the candle.

You should banish functional fixedness in the kitchen. In learning to cook, you’ll learn the most by figuring out the why behind each step in a recipe and exploring different possible answers. Even if you guess wrong, you’ll learn what does and doesn’t work, and in the process slowly build up a new, “functionally unfixed” view of the kitchen.

Duncker’s Candle Problem:

how would you mount a candle to a wall, given a box of thumbtacks and a book of matches?

Know Your Cooking Style

Part of learning to think like a geek is understanding your temperament and style in the kitchen. Most of us think of there being two types of chefs: cooks and bakers. (Personally, I think there are two types of people: those who divide people into two kinds, and those who don’t.) Cooks have a reputation for an intuitive, “toss it into the pan” approach, pulling together whatever ingredients inspire them and correcting as they go. Bakers are typically described as precise, exact in their measurements, and methodically organized. Even culinary schools such as Le Cordon Bleu split their programs into cooking (“cuisine”) and baking (“patisserie”), due to the differences in technique and execution. Professional line cooking requires prep work and then an on-demand, “order in!” portion. Professional pastry baking is almost always done production-style with a different set of techniques and completed well in advance of when the order comes in. For most of us cooking isn’t a profession, though, so dividing culinary types into two isn’t useful.

The most helpful way of thinking about types of cooks that I’ve come across is the research done by Brian Wansink, the director of the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab and author of Mindless Eating (Bantam, 2006). Brian’s work is fascinating, finding all sorts of patterns in eating behaviors that can then be used to create healthier eating patterns.

Based on a survey of about a thousand home chefs from North America, Brian found five different types of cooks. With his permission, I’m reproducing his short quiz here. It’s fun to see that any food TV show or cooking magazine that I can think of falls neatly into one of these five categories. In his research, he found that most people were roughly equally split between the five types that describe about 80–85% of us. The other 15–20% end up being combinations of two or three types, so don’t sweat it if you take the quiz and don’t fall squarely into one category. What I’ve found in talking with some geekier audiences—full of scientists and software engineers—is a huge bias toward the innovative type of cook. There’s clearly a personality bent in these fields!

When cooking for others, keep in mind the possible combinations of different types of cooks and, by extension, eaters. Imagine you’re a health-driven eater being given food by someone who is a giving cook, who expresses affection with food. That plate of brownies is their way of saying, “I care about you!” So enjoy one, or at least a nibble, and say thanks. When I asked Brian about conflicts between the eating styles of people who live together, he suggested sharing the cooking responsibilities: take turns doing the cooking, giving the regular cook a night off at least once a week.

How to Read a Recipe

It’s easy: start at the beginning and finish at the end. Ha! If only. Recipes are documentation of what works for their authors; suggestions from one chef to another. When looking at a recipe, realize that it’s not only a suggestion, but an abbreviated one. Give the same recipe to a dozen different chefs, and you’ll get a dozen different variations.

The first time I follow a recipe, I stick to it. I’ve learned many things this way—turns out, you can peel red bell peppers (the peel has an herbaceous, grassy, bitter taste). For a new cake recipe, I might think the batter looks too runny (needs more flour?) or too thick (add more oil?), but I go with it. After I’ve made it once, though, all bets are off. The next time I’ll tweak it based on notes and memories from the first time.

If you’re new to cooking, start with breakfast. It’s the meal that we’re most likely to eat at home, and the recipes are the easiest to learn. Plus, breakfast meals are quick to make and the ingredients are cheap. (One friend told me about learning to debone meat in culinary school. It basically amounted to “Do it 100 times, and by the time you’re done, you’ll know how to do it.” No wonder culinary school is so expensive!)

• Understand the “why?” behind each step in the recipe. I’ve watched chemists—experts trained at following instructions—skip right over the step that says “turn off heat” in a recipe that involves melting chocolate in simmering liquid. “Turn off heat? But melting things requires heat!” That recipe used the residual heat from the liquid to melt the chocolate to prevent it from being burnt.

• Practice mise en place—French for “put in place.” Start by prepping your ingredients before you begin the cooking process. Read through the entire recipe, and get out everything you need so you don’t have to go hunting in the cupboards or the fridge halfway through, only to discover you’re short of a critical ingredient. Making stir-fry? Slice the vegetables into a bowl and set it aside before you start cooking.

• Follow order of operations. “3 tablespoons bittersweet chocolate, chopped” is not the same thing as “3 tablespoons chopped bittersweet chocolate.” The former calls for 3 tablespoons of chocolate that is then chopped up (taking up more than 3 tablespoons), whereas the latter refers to a measure of chocolate that has already been chopped.

• When a recipe calls for something “to taste,” add a pinch, taste it, and continue adding until you think it is balanced. Ingredients vary, so balancing flavors depends on the specifics of the ingredients you have on hand. Also, what constitutes balanced is a matter of cultural background and personal preference, especially when you’re using seasoning ingredients such as salt, pepper, lemon juice, vinegar, and hot sauce.

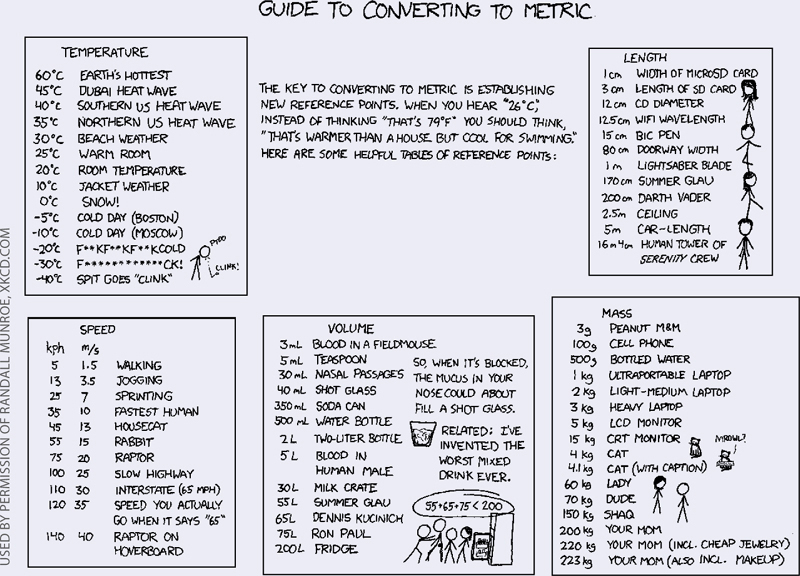

Need to convert between standard and metric measurements for ingredients?

Check out Wolfram|Alpha (http://www.wolframalpha.com). Enter “1 tablespoon sugar” and it’ll tell you it weighs 13 grams; enter the ingredients for the pancake recipe using a “+” between them and it’ll tell you the combined ingredients have 38 grams of fat, 189 grams of carbs, and 46 grams of protein.

Always read through the entire recipe, top to bottom, before starting.

Fear in the Kitchen

The only real stumbling block is fear of failure. In cooking you’ve got to have a what-the-hell attitude.

—Julia Child

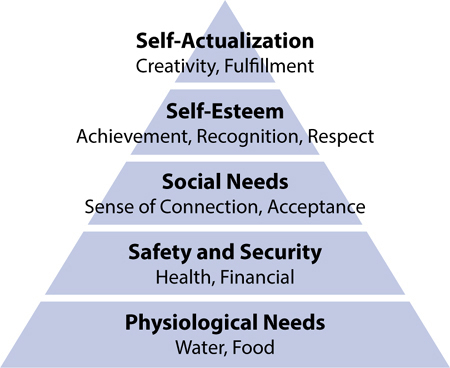

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs with areas related to food and cooking.

This is my pep talk for readers who are afraid of the kitchen. For some, the idea of stepping into the kitchen sets off panic attacks as the primitive parts of the brain take over. (If it helps, you can blame your brain’s locus coeruleus. It’s not your fault; take a few deep breaths to relax it.)

Fear in the kitchen can come from many sources but invariably boils down to fear of rejection and fear of failure. Why someone fears something depends on what needs are at stake. Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, was looking at what motivates human behavior in 1943 when he created his hierarchy of needs, putting what he considered the more basic human needs at the bottom of a pyramid. While his ranking of the needs hasn’t held up to scrutiny, the needs themselves give a good framework for looking at kitchen fears. The most common fears I’ve seen about cooking involve social needs and self-esteem.

First up, social needs. Cooking for others is a powerful way of building friendships and community, and bringing people together over a good meal is immensely rewarding. But there is also trepidation: what happens if you utterly ruin the food that you’re cooking? To overcome this fear, start by redefining what happens when food is ruined. So what if you ruin the dinner? Sure, there are physiological needs (one solution: order delivery) and a financial impact. But if your fears are based on social needs, the food doesn’t actually matter. As long as you’re bringing people together and treating them well, you’ll be meeting your needs—and theirs. (Humor goes a long ways to getting over fear—“Remember that time we served cereal for dinner and laughed about it?”) People are far more likely to remember how you made them feel than the food you served. What’s important is who’s at the table, not what’s on the plates.

Then there’s self-esteem. Low self-esteem comes from comparing ourselves to others and caring too much about what others think. We’re bombarded with magazine covers promoting the perfect holiday meal (“so easy, so elegant!”) and online posts showing amazing culinary creations. Then when we go to try that “easy” recipe with the beautiful photograph, we expect the same outcome. These comparisons aren’t valid. Aspirational magazines—and, sadly, many scientific papers—publish their best results instead of their more obtainable average results. Can you picture a glossy cooking magazine with all the photographs of perfect meals replaced with ones capturing a home cook’s version?! For self-esteem challenges, instead of making impossible comparisons, accept yourself for who you are and accept whatever it is you’ve made. (Unless, of course, it’s utterly burned, in which case see the previous paragraph.)

Julia Child’s appeal lay in her almost-average abilities and her “nothing special” humble aura (plus buckets of tenacity). Like her, try things with a what-the-hell attitude. Expect to drop the chicken on the floor once in a while. Play around with various ingredients and techniques. Come up with projects you want to try. (Mmm, bacon and egg breakfast pizza.) So what if you drop the chicken or burn the dinner?! If you’re enjoying yourself, does it matter? As the famed psychologist Albert Ellis quipped: “Only you can make you feel guilty!”

How much better off would we be if we talked about “success in learning” instead of “failure in the kitchen”? There’s not much to learn when things work. When things fail, you have a chance to understand where the boundary conditions are and an opportunity to learn how to do something better next time. Philosopher Alain de Botton gave a fantastic speech on this definition of success at the 2009 TED Conference. See http://cookingforgeeks.com/book/botton/ to watch his talk, “A kinder, gentler philosophy of success.”

Give learning time. You might have days when you feel like you’ve learned nothing, but the cumulative result will lead to insights. If a recipe doesn’t work as well as you’d have liked, try to figure out why. The recipe might simply be too advanced or poorly written. If you’re not happy with the results, try a different source of recipes.

The way to get over the fear in cooking is to understand what needs you’re trying to meet and not allow anxieties around those needs to bubble over elsewhere. Treat cooking as an experiment and bring that smart geek curiosity to the kitchen. Approach it as a fun puzzle to solve, where you get to pick the pieces.

If you’re nervous about cooking for others—a romantic date?—practice cooking the meal you’ve chosen the day before for just yourself and a confidant. This will make the routine of cooking the meal more familiar, reducing fear. It’s entirely okay to screw up and toss it in the trash; it’s no different than a science experiment that didn’t pan out (pardon the bad pun).

A Brief History of the Recipe

We’ve been writing about food for as long as we’ve been writing. The oldest known tablets, from the beginning of written civilization, show glyphs for beer, fish, and eating. The oldest known recipe dates to four millennia ago and describes a ritual for making beer. Like its cousin, bread, beer was a food of necessity. Beer was safer to drink than potentially polluted water, so ritualizing and recording the process of making it created a recipe of necessity and survival.

The ancient Romans expanded on recipes of necessity to recipes of indulgence (roasted flamingo, anybody?). While more complicated, their recipes still read more like short notes than precise protocols with measurements and descriptive steps.

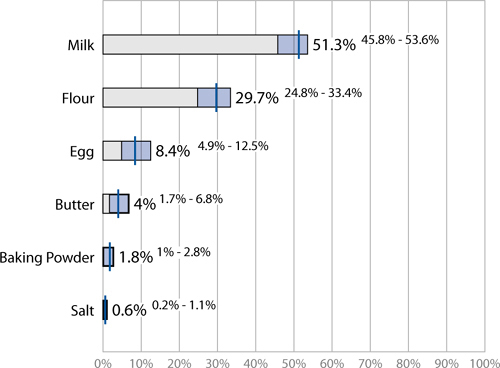

Golden Corn Cake.

¾ cup corn meal.

1¼ cups flour.

¼ cup sugar.

4 teaspoons baking powder.

½ teaspoon salt.

1 cup milk.

1 egg.

1 tablespoon melted butter.

Mix and sift dry ingredients; add milk, egg well beaten, and butter; bake in shallow buttered pan in hot oven twenty minutes.

It wasn’t until the 1800s that cookbooks began to give more precise measurements, with Fannie Farmer’s the Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (Little, Brown & Company, 1896) being a notable early bellwether in the United States. Her book is still enjoyable today. Here is her recipe for what we’d call cornbread (although I think her name, Golden Corn Cake, is more apt).

Fannie Farmer’s book sold 4 million copies, changed the way we cooked, and set the stage for Irma Rombauer’s culinary classic Joy of Cooking (1931), which to date has sold 18 million copies. Ironically, both authors had difficulty with their initial printings, having to pay for the initial print runs themselves. Breaking the status quo has never been easy.

Joy’s innovation was “casual culinary chat,” weaving in the ingredient lists with the instructions that give the reader a description of what to look for. It’s one of the first books to walk the reader through the process of cooking, serving as both a culinary guide and source of notes for the aspiring cook. (Growing up and thumbing through my mom’s copy of the 1975 edition, I remember reading “How to Skin a Squirrel,” which made an impression on me of what cooking was like only a few generations ago. Plus, ewww. The latest edition has understandably dropped that section.)

Even modern recipes that inherit Fannie Farmer’s precise measurements and Joy’s woven narrative should still be viewed as notes from one cook to another. There’s simply too much variability in ingredients and preferences. A teaspoon of dried oregano in your drawer won’t necessarily be the same strength as a teaspoon of the dried oregano in my drawer, due to age, breakdown of the chemicals (carvacrol, in this case), and variations in production and processing. And food preferences are just too varied—there simply is no “perfect” chocolate chip cookie; we each have our own version.

What will the future of recipes look like? While I don’t believe—or choose not to believe!—that printed cookbooks will go away, we are clearly in the digital age. Books no longer need to be authoritative or exhaustive, but should be entertaining and inspirational. With Internet access becoming universal, you’ll be able to find a good recipe for chicken tagine or tofu scramble faster with an online search than by flipping to the index at the back of this book. Fannie Farmer and Irma Rombauer would be amazed.

When will we see a dynamically generated cookbook with recipes tailored to our individual tastes—emphasizing slow food, or healthy meals, or low-sugar recipes? Or recipe generators that allow us to choose our own parameters? “Computer, change the recipe to make the cookies crispier!” Some attempts at this exist, but they haven’t been breakout successes. In part, digital ebook formats don’t have the capabilities, and installing apps is a higher barrier than most creators imagine.

I also think we’ve reached a simplicity point: cooking for pleasure is a pastime. We find it enjoyable to have a challenge rewarded with success. I call this maker’s gratification: the emotional reward and sense of accomplishment that one gets by making something that has some level of difficulty. Good brownies, made from scratch, are gratifying to make and to eat. The food industry understands this all too well. Instant brownie mixes could be formulated to not need eggs, oil, and water, but then they wouldn’t deliver maker’s gratification. How much reward would you feel for putting a store-bought pan with batter into the oven and hitting the “on” button? Probably not much.

Condensed recipes, like those that Maureen Evans posts on Twitter (@cookbook), are easy to follow for experienced cooks:

Lemon Lentil Soup: mince onion&celery&carrot&garlic; cvr@low7m+3T oil. Simmer40m+4c broth/c puylentil/thyme&bay&lemzest. Puree+lemjuice/s+p.

Regardless of the source and format of a recipe—short note, culinary essay, flowchart, or whatever may come—read it thinking of the source and the author’s intent, translating as necessary in order to achieve what you want.

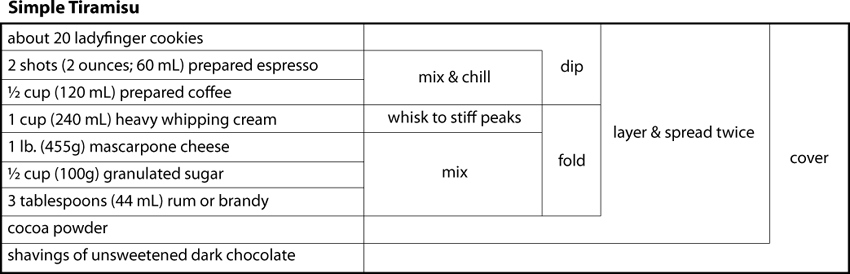

Visual recipes, like Michael Chu’s (http://www.cookingforengineers.com) tiramisu, communicate quantities and steps with minimal overhead using a time and activity chart:

Don’t Always Follow the Recipe

Recipes shouldn’t be blindly followed, for a bunch of reasons:

• Recipes can’t be written to exact measurements. There’s too much variability in ingredients and techniques: mixing 3 cups of flour and 1 cup of water won’t reproduce the same results every time or for every cook. Professional bread bakers know to vary the amount of water based on weather (flour is moister with higher humidity) and the amount of yeast based on time of year (using more in the winter, when it works slower). Gain experience by paying attention to how dishes look and feel, and tweak quantities to get things to look and react like they did previously.

• Some recipes are just concepts. Stone soup? Kitchen sink salad? Congee? I can tell you what I did, based on what produce I found in my market, but you’d have to adapt. The recipe for congee, as you’ll see on the next page, is hardly a recipe, but it’s still written up with measurements and instructions. You’ll only need to read it once; after that, you’ll know the concept and never need the recipe again.

• Go off-recipe! Maybe you don’t like the taste of one suggested ingredient and want to substitute something else. Maybe you’ve read a few recipes for a dish and want to mix up the seasoning or vegetables. Recipes aren’t written in stone. (Well, excluding that beer recipe by the ancient Egyptians I mentioned earlier.)

A/B experiment to myth-bust. Make a recipe twice, changing just one thing (cookies: melt the butter or not?), and see what changes (if anything). If you’re not sure which way to do something, try both and see what happens. You’re guaranteed to learn something—possibly something the recipe writer didn’t even understand.

And finally, following recipes kills innovation. I often turn to the cuisine of different cultures, looking at their “flavor families,” or regional ingredients that are considered complementary. Lemon, tarragon, and wine—a common combination in French dishes—are pleasing together. Elsewhere it might be lemon, rosemary, and garlic. There are tons of regionally based cookbooks—pick up one that covers a region of interest to you. I find books from regions where two or more cultures mix together (Morocco, Israel, Vietnam) to be the most thought-provoking. The way techniques and ingredients get blended together is fascinating.

For off-recipe ingredients and inspiration, explore ethnic supermarkets and mom-and-pop stores. These tend to be small storefronts with new smells from the unfamiliar produce and spices and are typically located in old-style ethnic neighborhoods. Ask around to discover where they’re hidden. They can be amazing finds and introduce you to ingredients that will change the way you cook for the rest of your life—which won’t happen if you stick to the recipes you have.

A Place for Everything and Everything in Its Place

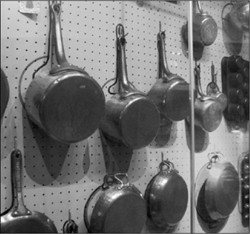

Not everyone is the neat-and-tidy type, but if there were ever a place to try to keep things in order, your kitchen would be it. Julia Child took the adage “a place for everything and everything in its place” seriously: pans were hung on pegboards that had outlines drawn around each item to ensure that it was always returned to the same location. Knives were stored above countertops on magnetic bars where she could easily reach out to take one. Common cooking items—spoons, whisks, oil, vermouth—were placed next to her stovetop. Her kitchen was organized around what the French call near to hand, with common tools and ingredients kept near where they would normally be used.

You should do the same thing in your kitchen. Every item should have a home location, to the point where you could hypothetically grab a particular tool or pan while blindfolded. (This isn’t hypothetical for the blind.) Store tools near the foods with which they are used: measuring spoons with the spices, garlic press with the garlic, and measuring cups with the dry goods. Speaking of dry goods, make sure to label any bulk goods with both what they are and their purchase date to avoid potentially unpleasant surprises months (years?!) later.

Keep often-used things out where you can reach them quickly. Every kitchen should have a container for spoons and spatulas next to the stove, and every kitchen should have a good, foot-pedal-operated trashcan right next to the cutting board. A good trashcan seems like an odd suggestion, but it’s way easier than having to open the cupboard below the kitchen sink while your hands are full of onion skins and whatnot. Consider removing cupboard doors as well, if the aesthetic appeals—having plates and bowls where you can reach out and grab them speeds things up. These tweaks are individually small, but you will be amazed at how much time they save when added up.

Countertop space is precious, so move rarely used appliances to cupboards. Anything in your cupboards that you haven’t used for more than a year should be foisted off on others. If you’re not sure you can part with some rarely used gadget (“but that’s the mango slicer from our honeymoon!”), find another home for it, outside the kitchen. If you find the idea of a marathon pruning session overwhelming, try doing one cupboard per week. Still too overwhelming? Remove one thing a day, no matter how small, until you reach a Zen state of tranquility. Keeping the kitchen functional is much easier as an ongoing habit than an annual ritual.

A Dinner Party for One

We should celebrate our opportunities to eat alone. How we cook and eat when no one is looking is fascinating: a bowl of cereal, bread and cheese, fried spam (!), takeout. There’s nobody else to please and no one to judge. Indulge yourself!

It needn’t take time if you’re busy. Scrounge for dessert while eating your dinner. Eat and read at the same time. Take the opportunity to think about what makes you happy. Set out a placemat. Pour yourself a drink. For the busy parent or working professional, eating alone should be a treat: a time to take care of yourself in whatever way you like.

Some tips for when you’re cooking solo: amortize costs by picking recipes that share ingredients. Extra tomatoes and cilantro purchased for a chicken dish can be used with eggs the next morning. Transform cooked chicken and vegetables from dinner into a sandwich. If your grocery store has a salad bar, look there for ingredients. Need a handful of cilantro? Snag the amount you need, already diced and sometimes cheaper than in the produce section.

The Power of a Dinner Party

Cooking and entertaining others has the amazing power of bringing people together. As the host, you’re able to create an experience exactly the way you want, from table settings to music. Don’t be scared of cooking for others, whether it’s a dinner party, brunch, elevenses, or any other meal. As I mentioned earlier when talking about fears in the kitchen, dinner parties are not about the perfection of the food. Bringing people together over food is about engaging in lively conversation and fostering community.

Here are some quick pointers if you’re new to throwing dinner parties or brunches:

• Bring people together with intent, thinking about whom you’re inviting and how they’ll get along with other guests. When extending an invitation, be clear if it extends to others (specifying “and guest” or “ and friends”), and set expectations (should your guests arrive at 7 pm sharp, 7-ish, or anytime? are you serving food or just snacks?).

• There’s an unofficial protocol in accepting dinner party invitations. It varies depending upon occasion and type of relationship, but when unsure, follow this script: guests should offer to bring something (“What can I bring?”), hosts should demur (“Just yourself!”), and guests should show up with something anyway (a bottle of whatever for the host to enjoy that night or another evening).

• Ask about allergies ahead of time. If you are cooking for someone with a true food allergy, you should take extra precautions. Likewise, if you have allergies yourself and are invited somewhere, it’s your duty to let the host know when you reply to the invitation; you may want to offer to bring a single portion of something for yourself to unburden the host from meeting your needs.

Take a look at page 445 for information on food allergies and common substitutions.

• Some guests may be following a restricted diet, either limiting certain types of foods (e.g., vegetarians don’t eat fish or meat, vegans avoid any animal products, and lacto-ovo-pescatarians eat milk, eggs, and seafood but no other meats) or limiting certain classes of foods (e.g., saturated fats, simple carbs, or salty foods). Then there are religious observations (e.g., kosher, halal). Regardless, if you’re up for the cooking constraints, talk with the guests to agree on something that suits their needs.

• Choose recipes that leave you time to spend with your guests. They’re there to see you! That doesn’t mean you need to have everything ready before guests arrive. Spending time with guests as you put together a meal can be a lovely beginning to an evening, as long as it lines up with what your guests expect.

• Have appetizers for your guests to snack on before you serve the meal. Simple things like bread and cheese, pita and hummus, or fresh fruit (grapes) and vegetables (carrots and dip) are quick, easy, and useful for guests who are hungry before the meal is ready.

Presentation and Plating

“Looks delicious!” is a seemingly impossible phrase. How can you see what something will taste like? Presentation and plating—the arrangement of food on a plate—set an expectation for how food will taste, and when cooking for others, can be a powerful signal of much more than taste and flavor.

Food presentation is a form of signaling, most easily understood by looking at what biologists call signaling theory. In biology, animals use signals to communicate many intentions. Bright red coloration on frogs signals “poison!”, warding off predators. With time, other animals mimic the signals—imagine non–poisonous frogs that happen to be red—which leads to a race between honest signalers and copycats. This is why harder–to–copy signals replace older, copyable ones. Some gazelles ward off predators by pronking (now there’s a Scrabble word), jumping up high to demonstrate that they can also run fast. The cheetah that sees a gazelle pronk quickly learns that the gazelle isn’t worth chasing, saving both the cheetah and the gazelle an energy–intensive race. Weaker gazelles can’t copy the honest signal and suffer.

Humans use signaling too. Expensive sports cars aren’t practical, at least for driving around town, but they do signal one’s economic status. (Incidentally, this is why high-end sports cars have only two seats and little storage space: if the car were practical for daily chores, then it wouldn’t be a good signal of wealth.) Cooking from scratch and spending time making a meal is a signal, letting others know that you value them. Inviting guests over and preparing food for them is a huge signal. Signaling theory partly explains why things like instant brownie mixes call for eggs and oil: in addition to the maker’s gratification I wrote about earlier in this chapter, requiring those ingredients leaves just enough work that the baker can signal their care.

Different situations require different signals to communicate a message, and this makes writing a universal list of “how to plate food” tricky. To understand presentation, one has to understand the message that one is trying to communicate and then pick the appropriate signal for the context. If you’re cooking an everyday meal, you wouldn’t want a fussy presentation. (Using a fussy, special presentation on an everyday occasion would be its own signal, perhaps softening the blow of imminent bad news.) If it’s a special date night, setting out cloth napkins and spending time on the way the food is plated is a way of signaling that it’s a special occasion. And with good friends, setting up an environment that matches the expectations of your social circle communicates your understanding of the group norms. Following a fine-dining restaurant-style presentation can be charming, or can come across aggrandizing, depending upon your peers.

Here are a few basic presentation tips if you do want to present food using appearances common to Western fine-dining.

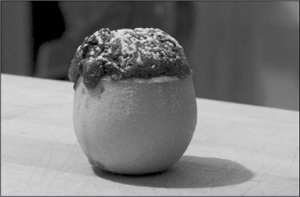

Match the color and size of the plate to the food. I’ve been surprised what a difference using a large plate can make; it’s like a frame around a picture. Some empty space on a plate is good! Color, too, can be instrumental. I find having two sets of plates—mine are either white or dark grey—makes it easier to pick one that contrasts well with the food. You can add color to a dish with food: a few herb leaves on the top of a bowl of soup, a dusting of freshly ground black pepper on roasted chicken breast, or powdered sugar on a chocolate dessert all add visual interest to otherwise monochromatic dishes.

Make it look different than traditional home-cooking. If you’re plating a meal that has a vegetable, starch, and protein component, traditionally the three items would be placed next to each other, like wedges of a circle. Try placing the starch in the center of the plate and spreading it out in a thin layer, then adding the vegetable component on top of the starch, and finally stacking the protein on top of the vegetables. (If you want to go for extreme height, use a large can with both its top and bottom removed and stack the food inside it, and then slide the can up and away.)

Think about the size and arrangement of the food. All the rules of visual composition taught in art class (preschool counts!) apply to plating food. The “rule of odds” is one of the easiest: seeing either three or five meatballs on top of a bowl of pasta is generally considered more visually interesting than seeing four or six. Contrasts in size and shape help, too. If you’re serving pork chops, try slicing them into two pieces and placing one part angled up on top of the other. This will show the interior of the chop, both revealing how the meat is cooked and adding visual interest from arrangement and color contrast.

The Basics of Kitchen Equipment

Figuring out which tools to have in your kitchen can be a daunting task. With so many products on the market, the number of choices you have can be overwhelming, especially for overly analytical perfectionists (you know who you are). What type of knife should I buy? Which pan is right for me? Should I buy that cherry pitter?

Take a deep breath and relax. To a newbie, kitchen equipment probably seems like the secret to success, but in all honesty, it isn’t that important. A sharp knife, a pan, a cutting board, and a spoon to stir with, and you’re covered for 80% of the recipes out there and have more kitchen equipment than 90% of the world’s population. Heck, in some parts of the world, people just have one pot and a spatula that’s been sharpened on one side to double as a knife.

Having good tools does make cooking more enjoyable. The right answer for which model of equipment to buy is: whatever works for you, is comfortable, and is safe. The next few pages offer my take on kitchen gear, but it’s up to you to experiment. Modify my suggestions to fit your needs.

The best kitchen gear tip that I can offer is this: look for a commercial restaurant supply store. These stores stock aisle after aisle of every conceivable cooking, serving, and dining room product, down to the “Please wait to be seated” signs. If you can’t find such a store, the Internet, as they say, “is your friend”: you can order anything online.

Use your hands when cooking! They’re the best tool in the kitchen. After a good scrubbing with soap, they’re just as clean as anything else and infinitely more dexterous. Tearing lettuce leaves? Squeezing a lemon? Putting the entrée on a plate? Use your hands.

Also, learn what various temperatures feel like: hold your hand above a hot pan, and notice how far away you can still “feel” the heat. Stick your hand in an oven set to medium heat, remember that feeling, then compare it to when you’re working with a hot oven. For liquids, you can generally put your hand in water at around 130°F / 55°C for a second or two, but at 140°F / 60°C it’ll pretty much be a reflexive “ouch!”

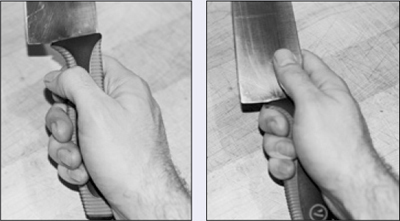

Knives

Knives are humankind’s oldest and most important tool, for good reason: they make cooking and eating possible. Cooking—preparing food for eating, in its most basic sense—is what created society, and over time, better knives advanced our ability to prepare food. Metal blades replaced ones of flint and obsidian, and this ability to work with metal literally defined the boundary between the Stone Age and the beginnings of historical times in some parts of the world.

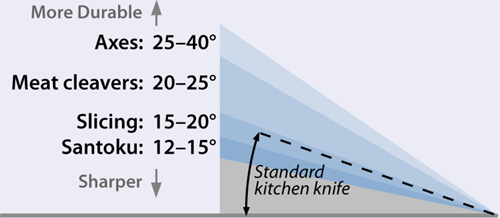

Steel replaced other metals—bronze, iron—some 4,000 years ago, and presumably shortly thereafter was forged for culinary purposes. Modern steel knife blades are now manufactured in one of two ways: forging and stamping. Forged blades tend to be heavier and “drag” through cuts better due to the additional material present in the blade. Stamped blades are lighter and tend to be cheaper because of the way they’re manufactured. Which type of knife is better is highly subjective; to some, knives are a very personal choice. Personally, I’m perfectly happy with cheaper stamped knives. Make sure you know how the knife feels in your hand before you buy it!

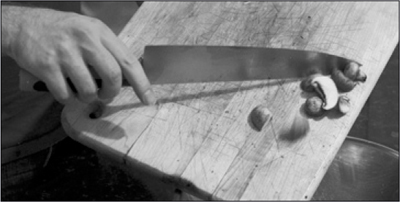

Regardless of material when cutting, you should “pull” the knife through the food (don’t just press straight down, except for soft foods like cheese or a banana, and don’t “saw”; use smooth, long motions). Here are the three knives everyone should have:

Chef’s knife. A typical chef’s knife is between 8” / 20 cm and 10” / 25 cm long and has a slightly curved blade; this allows for rocking the blade for chopping and pulling the blade through foods. If you have smaller hands, you might want to look at a Santoku-style knife, a Japanese-inspired design that has an almost flat blade and a thinner cross section that’s best suited for straight up-and-down cutting motions.

Paring knife. A paring knife has a small (~4” / 10 cm) blade and is designed so you can hold the knife in one hand and the food item in the other, for tasks such as removing the core from an apple quarter or cutting out bad spots on a potato. The almost pencil-like grip design of some commercial paring knives allows you to rotate the knife between your fingers, so you cut around something by rotating the knife instead of rotating the food item.

Bread knife. A bread knife has a serrated blade, typically between 6” / 15 cm and 10” / 25 cm long. While not an everyday knife, they’re handy for cutting items besides bread: oranges, grapefruits, melons, and tomatoes all cut more easily with a serrated blade.

Cutting Boards

Cutting boards come in two main varieties: wooden and synthetic. Wooden cutting boards are made of close-grained hardwoods like maple or walnut and have a lovely, warm feel; synthetic boards are made of plastics like nylon or polyethylene and have the benefit of price. Avoid using glass or stone cutting boards for anything other than serving; they dull knives.

Which material is safer depends. Running a cutting board through a dishwasher sterilizes it, killing any salmonella or E. coli present from meats or unwashed veggies. Wooden cutting boards aren’t dishwasher safe—hot water warps wood—but wooden cutting boards are more forgiving to lapses in sanitization due to the chemical properties of wood. Researchers have found that home chefs using plastic cutting boards were twice as likely to contract salmonellosis than those using wooden cutting boards, even when they hand-washed the board after contact with raw meat. If you use synthetic cutting boards, make sure to wash them properly.

Use the butcher paper that meats come in as an impromptu disposable cutting board for them. One less dish to wash!

Personally, I use a plastic cutting board for raw meats and a wooden one for cooked items because I find the difference to be an easy visual reminder, and if I do slip up on washing one correctly, there’s less chance of cross-contamination. Beyond the food safety issues, there are a couple of practical aspects to keep in mind:

• Look for cutting boards that are at least 12” × 18” (30 cm × 45 cm); too small, and you won’t have space to chop or dice things.

• Some cutting boards have a groove around the edge to prevent liquids from running over the side. This is handy when you’re working with wet items, but it makes transferring dry items, such as diced herbs, more difficult. Keep this in mind when choosing a board.

• If your board starts to smell (say, from working with garlic or fish), use lemon juice and salt to neutralize the odors.

• Place a kitchen towel under your cutting board to prevent it from moving while you’re working.

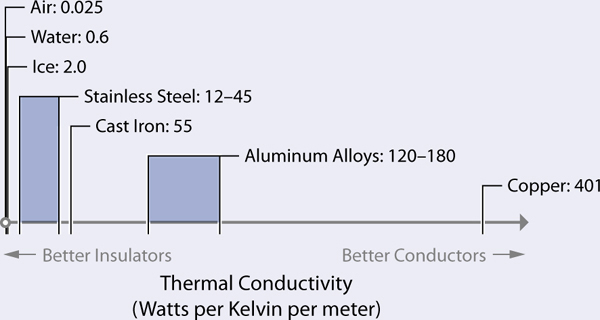

Pots and Pans

I like to think I have a minimalist kitchen at the moment, having downsized in a recent move, but even so, my collection of pots and pans numbers five: two frying pans (one with a nonstick coating), a saucepan (an odd-lot one I picked up in college), a stockpot (thanks, Dad!), and a small cast iron pot. The cost of these five pans probably adds up to more than the rest of my current kitchen gear combined. That strikes me as about right.

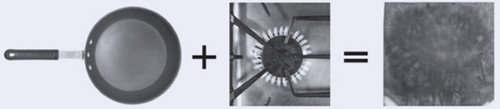

Frying pans are shallow, wide pans with slightly sloped edges. If you can only have one pan, get a nonstick frying pan—it’s the easiest to use. Since nonstick coatings prevent the formation of fond (the bits of food that brown in the bottom of the pan and add flavor to sauces), consider purchasing a stainless steel frying pan as well.

Saucepans, roughly as wide as they are tall and with straight sides, hold a few quarts/liters of liquid. Look for a pan that has a thick base, as this will avoid hot spots. Make sure to pick up a lid as well; they’re sometimes sold separately.

Stockpots hold a gallon or more of liquid (~4+ liters) and are useful for blanching vegetables, cooking pasta, and making soups. The stockpot I use is one of the cheap stainless steel commercial varieties. Be sure to snag a lid!

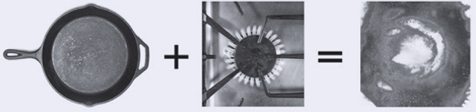

Cast iron pans have a much higher thermal mass than other pans, making them ideal for searing foods. Certain sizes are also great for baking dishes like cornbread. Avoid stewing highly acidic ingredients such as tomatoes in cast iron; they’ll react chemically. Always, always dry your cast iron pan after washing: clean it by rinsing and optionally scrubbing with a plastic scouring pad (or salt and a towel), heat it over a burner for a minute, and then wipe the inside with a very thin layer of oil.

What’s seasoning a cast iron pan mean?

Seasoning is culinary lingo for developing a nonstick finish based on fats that have been heated high enough to break down and bond to each other and the pan’s surface.

You should season new pans (or reseason old ones in need of care) by thoroughly scrubbing them with soapy water, drying them on a burner for a minute, and then coating all sides with a thin layer of fat. Traditionally lard or tallow was used, although any oil should work; some cooks swear by raw flaxseed oil. Wipe away as much of the oil as possible, place the pan in the oven, set the oven to 500°F / 260°C, bake for 60–90 minutes, and then turn the oven off and allow the pan to cool inside. Repeat a few times if the finish seems too thin, or just do the wipe and baking steps as part of regular post-use cleaning the first few times you use the pan.

How do they get a nonstick coating to stick to the pan if it doesn’t stick to anything?

By using a chemical that sticks to both the nonstick coating and the pan, called an adhesion promoter. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) is the adhesion promoter of choice these days. Unfortunately, it’s rather toxic, but according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), it’s used only as a processing aid during manufacturing, and manufacturers claim that it’s not present in the finished products.

Buy more than one frying pan so you can cook different components of a dish at the same time.

Kitchen Equipment Essentials

If you were to ask me for a shopping list for a brand new kitchen, I’d tell you to snag one of each type of knife and pan I mentioned earlier, a few cutting boards, and then the following list of “everything else.”

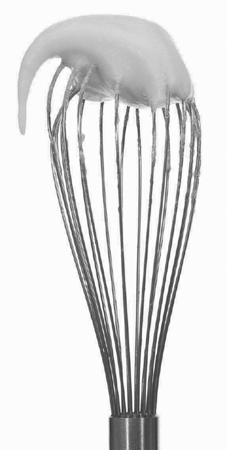

The “obvious” parts of “everything else” need merely a mention: a few wooden spoons for stirring, a whisk, bar towels, a kitchen timer, heat-safe metal measuring cups, a microwave-safe glass measuring cup for liquids, and measuring spoons. Then there are items where short comments may be useful to the culinarily uninitiated:

Metal and glass mixing bowls are easy to clean, cheap at commercial kitchen stores, and safe at low temperatures in the oven (for keeping cooked foods warm). Don’t use plastic ones; they’re far less versatile.

A silicone stirring spatula is perfect for scrambling eggs in a pan, folding egg whites into batters, and scraping down the edge of a bowl of cake batter. Silicone is a great material for cooking implements: it’s heat-stable up to 500°F / 260°C.

Tongs should be thought of as heatproof extensions of your fingers: useful for flipping French toast, turning chicken on the grill, and fetching ramekins out of the oven. I recommend spring-loaded tongs with scalloped-edge, heatproof silicone tips.

Kitchen shears are heavy-duty scissors useful for cutting through bones (see page 218) and trimming leafy greens (including as garnishes, such as snipping chives directly above a bowl of soup).

Garlic presses are great for more than garlic, if you get a heavy-duty one made of stainless steel. To use one with garlic, pop in an unpeeled clove, press, and then pull out the just-pressed peel and wash the press right away—5 seconds of work for fresh garlicky goodness. For ginger, slice off a thin piece, squeeze, and likewise, rinse the press immediately.

Immersion blenders, also called stick blenders, have a blade mounted onto a handle and are immersed into a container that holds whatever you want to blend, be it a smoothie, soup, or sauce. Quick to use, even quicker to wash.

Mixers shouldn’t be expensive: the cheapest hand-held mixer will work just fine; only splurge on a stand mixer if you’re baking a lot.

“Cream the butter and sugar” is a common step in recipes. Plenty is written about the microscopic air bubbles that the sugar crystals drag through the butter when they’re creamed. When you see a recipe call for creaming butter and sugar, use room-temperature butter—it needs to be plastic enough to hold on to the air bubbles yet soft enough to be workable—and use an electric mixer to thoroughly combine the ingredients until you have a light, creamy texture.

And finally, three items that are so worthwhile that I’m going to expand on their virtues:

A digital kitchen scale is a must-have item. Dry ingredients compress easily, so the amount of flour in “1 cup” will vary by a surprising amount. Digital scales solve this problem. Weighing ingredients also allows you to measure ingredients quickly. Look for a scale that has a flat surface on which you can place a bowl or dish and that’s capable of measuring up to at least 5 lbs (2.2 kg) in 0.05 ounce or one-gram increments.

Digital probe thermometers are awesome. Get one with a cable so that you can stick the probe into the food you’re cooking and set the controller to beep when it reaches the desired temperature. While timers are handy, time is just a proxy for temperature. Recipes that say “bake chicken for 20 minutes” assume it takes 20 minutes for the internal temperature of the chicken to reach 160°F / 71°C. Using a probe thermometer prevents overcooking: stick the probe in the chicken, set the alarm to beep at 150°F / 65°C, and when the alarm goes off, pull the chicken out of the oven. (Set the alarm a few degrees below the target temperature to allow for “carryover” heat to raise the temperature up the remaining few degrees.)

An electric pressure cooker with rice and slow-cook modes is another great tool. Some chemical processes in cooking require a long period of time at a relatively specific temperature. With pressure, you can cut six hours of cooking down to an hour. Electric pressure cookers are like automatic cars: you don’t get the same control as with an old-fashioned stovetop one, but you also don’t have to learn to press the clutch in or shift gears. Manual pressure cookers do have the advantage of slightly higher pressure and potentially faster heat-up times, plus no electronics to break. Still, if you’re new to them, I’d go electric, at least at first: they can safely be left on unattended without the worry of your kitchen burning down. This handy appliance makes an entire class of dishes (braised short ribs, duck confit, beef stew) trivially easy. Get a unit that also has rice and slow-cook modes (not everything is better “under pressure”); some units have settings for making yogurt and other temperature ranges too.

Do you need to weigh your flour? Yes! I asked 10 friends to measure out, then weigh, 1 cup of flour. The lightest weight reported was 124 grams; the heaviest, 163g. That’s a 31% difference!

Poke a probe thermometer into a quiche or pie to tell when the internal temperature indicates it is done—around 150°F / 65°C is hot enough to just set the egg custard without making a quiche dry.