EIGHT

The Heart of the Effort

There’s a poem by A. A. Milne (of Winnie-the-Pooh fame) called “The Old Sailor.” In the poem a shipwrecked sailor thinks of all the things he needs to do to survive on the island where he has washed up: make shelter, keep himself clothed and fed, protect himself from possible attack, perhaps even escape. But in the end, he becomes overwhelmed, not knowing how or where to begin . . . and so becomes paralyzed by indecision. In the last stanza of the poem, Milne writes “And so in the end he did nothing at all / But basked on the shingle wrapped up in a shawl.”25

This had a profound impact on me as a child (you notice I still remember it, all these years later); I never wanted to end up like the sailor, freezing up and doing nothing at all when confronted by a challenging situation. The Old Sailor is the ultimate example of avoiding change in a futile quest for a no-longer-available homeostasis. Sadly, we’ve seen many business and political leaders do something just like this when faced with the need for change—and they often do it at this particular point in a change. They see that a change is needed, and they know why it’s needed, and they might even have envisioned what the organization would look like, postchange. But then they start thinking about what it will actually take to make the change . . . and they retreat into simplistic half-measures, or no measures at all.

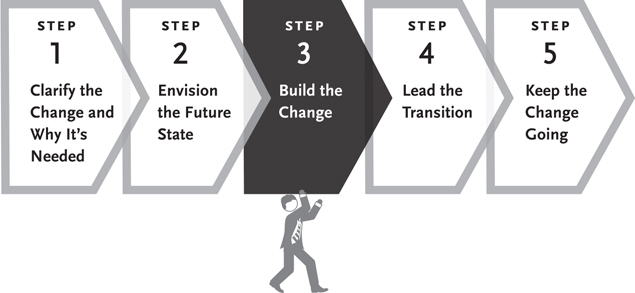

FIGURE 10. The five-step change model: STEP 3

A clear example of this was Borders’ reaction to Amazon, and specifically to the Kindle, in the early 2000s.26 I can only imagine the leaders at Borders had the data about how readers’ behavior was changing (buying online and moving to electronic readers), and that they saw the need to change. They probably even had some idea of what their business could look like after the change—after all, B&N created barnesandnoble.com and the Nook fairly early on in response to Amazon, so Borders had that as an example. I suspect that they, like the Old Sailor, looked at all the things they’d have to change in response to this new reality and simply froze up. In effect, Borders “did nothing but bask.” And they never were saved.

Step 3 of the change model gives you a way to move through this daunting point in your change journey—the point where you actually have to decide what to do, how to do it, and who will do it (Figure 10). The goals of this step provide a pathway to clarity and set you up to lead the organization through the change in Step 4. Those goals are to create the change team that will be responsible to move the change forward from this point; to identify and engage the key stakeholders—those who will most need to sponsor and/or influence the change (these people may be both within and outside the change team); to build the change plan; and—once you know what the change will require—to assess the organization’s readiness for the change.

——————GOAL #1——————

Create the Change Team

Leaders and Individuals

This is where the core team that has focused on the change during the first two steps will have to step back and think about who else needs to be involved. For a relatively small change, or in a small company, the group that has been thinking about the change through Steps 1 and 2 may actually be the change team: they are that core group who will now need to identify any other key stakeholders, create the change plan, and assess the organization’s readiness. But let’s assume for the moment that the leaders who have been focused on the change so far are not all going to be the change team; they are going to be determining a core change team that will be responsible for managing the organization through the remaining steps of the model.

If that’s the case, achieving this first goal requires truly effective delegation. Here’s what I mean: when you’re delegating a day-to-day job responsibility to someone who works for you, you need to make sure that the person is both capable and willing; you need to have a clear two-way agreement about what the responsibility entails; and you need to make sure you provide the support necessary for the person to be successful. In just the same way, when you and your fellow leaders are deciding who should be on the core change team, you need to make sure that the people you choose will want to be a part of the team and will have (or can quickly gain) the skills and mindset needed. You need to make clear agreements with them about what it means to be part of the change team and what will be expected of them. And finally, you need to be sure that you’ll be able to provide the support—the time, money, influence, and other resources needed—for them to be successful in their role.

You’ll also have to agree on who is going to be the leader of the change team. It may very well be you or one of your colleagues on the leadership team—but it doesn’t have to be. However, if it isn’t one of you, make sure that this person has the skills and attributes necessary for success in this role. In fact, let’s focus on what you and your colleagues will most need to do to select the best possible change team and get them started well. Choose wisely. Getting the right people on the change team, especially the person in the leader role, is key. Based on our experience, here are the most critical things to consider when choosing the ideal change team members:

• They work in a part of the organization that will be directly impacted by the change. You want people for whom this is not a theoretical exercise, but upon whom the change or changes will have a substantive effect.

• They have high credibility in the organization. You want their involvement to be viewed positively by others; this will go a long way toward ensuring the change is ultimately seen as “normal.”

• They have knowledge, expertise, or experience that will be helpful in making the change. This will be especially important when it’s time to create the change plan.

• They are open to the idea of change and can be “fair witnesses.” Although it’s important to support the team members in moving through their own change arc, you don’t want the team to spend time and energy on dealing with a teammate who’s deeply homeostasis-oriented, or who can’t be objective about what’s needed.

• They have the bandwidth to participate and their leaders’ endorsement. Having a great person who can’t put time into the change effort is frustrating for everyone.

• They want to be on the team. It’s important to resist the temptation to talk “perfect” candidates into being on the team. If they don’t really want to do it, they’ll tend to disappear when things get complicated or challenging.

The ideal leader of the change team will have all the preceding attributes, plus:

• They will have a proven track record of getting important things done well. This is the person who, more than anyone else, will be responsible for making sure there’s both a change plan, and a related transition plan, and that they get implemented. This person needs to be comfortable with the kind of ambiguity that arises in any large project—especially one that entails moving into uncharted territory—and they need to be persistent and solution-focused in the face of obstacles. If you don’t know that this person is good at completing important initiatives, it’s risky to choose them, no matter how smart, articulate, or well-connected they may be.

• They will have very high emotional intelligence and are effectively collaborative. This person will have to have great relationships with a wide variety of people—the change team, the change sponsor, the leadership team, the key stakeholders—and be able to support them to make agreements and decisions that are acceptable to everyone. If you’ve not seen this kind of ability from this person in the past, it’s unrealistic to expect they’ll suddenly be able to develop the skill in this high-pressure situation.

• They will be change-capable. This person needs more than the basic openness to change required of other team members. Look for someone who is very fluent at moving through change and at helping others do so as well.

All the members of the change team, especially the leader, need to understand what they’re signing up for. This is primarily on you and others who invite the change team members into the project; you need to be very clear about what the role entails. Make sure they’re clear on how much time will be involved over what period; the skills and knowledge they’ll need to have or build; and what they’ll be accountable for doing. Most important, they need to know that the change team is much more than simply a project team (although that is part of its remit): they and their colleagues on the team will not only be responsible for building and driving the nuts-and-bolts change plan but also for creating and supporting the transition plan that will help everyone move through their change arc as the change plan is implemented—and they will have to model and advocate for the change personally, in a balanced and authentic way. As Kevin Cashman has noted in Leadership from the Inside Out, “authentic leaders harness their gifts to serve something greater”—a great description of the role of the change team.27

Finally—and this is both important and often overlooked—don’t make the change team too large. This is a working team, and you want it to be able to operate efficiently and effectively. You want the team to be able to meet regularly and have most or all of the members present at each meeting. The least effective core change team I’ve ever experienced had thirty-five members; the most effective had eleven. Remember, team members can call on others outside the team to help in completing specific parts of the plan or understanding needed technologies or new approaches; those people don’t have to be members of the core team but can be part of extended teams that work closely with one or more core team members.

Take Them through Your Journey

Once you’ve chosen the leader and the team members, don’t forget the change arc. Unless this team is exactly the same group that’s been moving through Steps 1 and 2 together, you’ll need to support the change team members through proposed change and mindset shift before you ask them to begin to function as the core group that will lead the change from this point forward. The best way to do this is to take them through Steps 1 and 2 of the model in an interactive way.

As I noted earlier, this may be difficult. To many leaders, this feels like a big step backward (“But we’ve figured all this out already—why do we have to go through it all again?”). But remember, it’s not just a matter of communicating the information to the team. They have to go through their own mental and emotional change arc of proposed change, mindset shift, new behaviors, and finally change occurs. They won’t be able to start being effective members of the team until they’re well through their mindset shift and thinking of the postchange future as being relatively easy, rewarding, and normal.

Getting the Change Team Started

Here’s what we’ve seen work:

Prepare the leader. If the leader of the change team is a member of the leadership team that has already been thinking through the first two steps of the change, you’re in luck: they’re pre-prepared! If not, start by introducing them to the idea of the change arc and then the five-step change model as a way of supporting the whole organization to move through the change arc. Use information, stories, and experience to make your explanation three-dimensional. Most important, make sure it’s a conversation as opposed to a lecture: ask questions and encourage the new leader to ask questions, so you can find out how what you’re saying is landing, and whether you need to say more—or whether you need to draw out their questions or concerns and their own experience of change.

Once they seem comfortable with the idea of how change works, both for individuals and organizationally, you can take them through the work that’s been done on Steps 1 and 2 in your organization’s change: what the change is and why it’s needed, what the future will look like postchange, and how you’ve agreed to measure success. Again, make this a conversation, with lots of opportunity for dialogue and questions. Ideally, the leader will start asking questions like, “Have you thought of . . . ?” or “Is X a part of this . . . ?” If you have answers to their questions, great—share them. But if you don’t have answers, resist the temptation to make something up or dismiss them as unimportant at the moment. Instead, let the leader know these things haven’t yet been discussed and will be something for the change team to consider. In other words, use those questions as an opportunity to start treating this person as the leader of the change team. Finally, make sure that you and the team leader have a clear agreement about what their role will be. It’s important to have this clarity before the team meets for the first time. This way, you’ll know you’re on the same page, and the leader will be able to show up with clarity and confidence from the very beginning.

Have a kick-off meeting. This is where you begin to take the core change team through the steps you’ve already moved through with the leader. Here’s how the agenda for that first kick-off meeting might look:

• Welcome and introductions

• Goal of the meeting: to give attendees necessary background for being on this team

• How change works: the change arc and the change model

• What’s our change and why is it needed? (elevator pitch)

• Scope of the change

• Our hoped-for future once the change has happened (vision elements)

• How we’ll measure success

• Discussion: likes, concerns, and suggestions

• Next steps

Likes, concerns, and suggestions. Before we go on, let me introduce a remarkably useful tool for getting people engaged and bought into an idea, while obtaining their useful feedback about how to make it work. I learned this many years ago from a friend of mine, Mitch Ditkoff, who invented this tool as a way of supporting and encouraging creativity.28 Here’s how it works: when introducing an idea or approach to a group of people, first ask them what they like, appreciate, or find appealing about it. This gives you an immediate sense of where the group feels aligned with the idea or approach, and what parts of it they’re most likely to connect with and support. It also puts their brains into a “fair witness” frame—rather than just immediately keying into the negative, as many people have a tendency to do when faced with change (i.e., focusing on how it will be difficult, costly, and weird).

Next, ask them what concerns they have about what they’ve heard. Using the frame of “concerns” is much more helpful than simply “dislikes,” because when you ask for concerns, people have to think about what exactly doesn’t resonate for them or what they’re worried about. They may say things like “I’m worried that this will require a lot of technology we don’t have” or “I’m concerned that longtime employees might see this as overwhelming.” When you ask people what they “dislike,” they can be much more negative and superficial: they’re much more likely to say things like “We can’t do this” or “This is too much for people.” Once you’ve gathered the group’s concerns, it’s useful to look for and agree on themes: most groups, in most situations, will have a few concerns that are broadly shared and deeply felt.

Next, you’ll ask the group: “What suggestions do you have for addressing these key concerns?” This is the most effective and unexpected part of this approach. This is where you’re saying, in effect: “Okay, you’ve raised these issues—now help us figure out how we can resolve them.” A person can opine all day about how something won’t work, but when you invite them into figuring out how to address the things that aren’t working, that’s when most people start feeling some ownership for the success of the idea or the approach. In a change situation, this is when the team begins to take responsibility for actually being the core change team. And it’s a powerful mindset shifter: it really helps people start to transition from seeing the change as difficult, costly, and weird to looking for ways to make it easier, more rewarding, and more normal. Finally, it’s a great setup for the meetings ahead: let them know that in the next meeting, you’ll begin to focus on how to resolve those concerns as you identify key stakeholders and make a change plan.

Building past the first meeting. You (if you’re facilitating the meeting) or the change leader may have a strong urge to keep going at this point, to talk about everyone’s role on the team, how the team will operate, what the outputs will be, and so on. But be sensitive to the needs and capacity of the team. If most of the team is just being introduced to these ideas about how change works and to this change specifically, then they’re probably at the beginning of their change arc and need time to process and go through their own mindset shift. Make sure that they know that you’ll attend to these practical tasks (about their role, how the team will work, and what you’ll accomplish together) in the next meeting and—this is important—that they can come to the change leader with any questions they have between now and the next meeting.

The Second Meeting: Help Them Become a Team

The second meeting is when the leader will turn the team members’ attention toward each other and how they’ll operate together. In our work with teams we’ve seen that the most high-performing ones have five things in common: (1) they have clear goals that are compelling for everyone on the team; (2) they have ways of measuring progress toward those goals; (3) they have clearly defined roles that will allow them to achieve the goals; (4) they have good team processes—simple, efficient ways of working together and sharing information; and (5) they trust each other. With a core change team the overall goal is clear: they’re responsible for supporting the organization to achieve the postchange future that’s been envisioned. The measures of success in achieving that goal have already been established (at least in draft form). So, what’s needed now is to make sure they’re clear on their roles, that they have good, effective processes (ways of operating together), and that they begin to build trust with each other. To that end, the agenda for the change team’s second meeting might look something like this:

• Welcome back

• Goal of this meeting: to define how we’ll be a team

• Our team goal: to plan and drive the change

• Measures of success for the change: review

• Roles: discuss and agree on our role as team members (and team leader)

• Process: establishing our operating agreements—meetings, decision-making, information-sharing

• Building trust: making clear agreements about how we’ll support each other, including giving feedback and conflict resolution

• Next steps

These two meetings are foundational to the change team’s success: ignore or skip them at your peril. In our experience, if you conduct these two meetings with care and focus, you’ll most likely have a change team that is mentally, emotionally, and practically ready to begin planning the change and support the organization through it.

Ongoing Change-Team Cadence

Having these first two meetings is a great start—but it’s just a start. Since the change team will be the core driver through the remaining steps of the change, it’s critical to establish a regular cadence of meeting and communication after these first two level-setting meetings. Depending on how fast your change is moving, how complex it is, and how much coordination will be required among the various workstreams, you may decide to have brief daily stand-up meetings or more in-depth weekly status meetings. Deciding this—how and when these meetings will happen, what the standard agenda will be, who will facilitate them, and how outcomes will be noted and communicated—is part of the work of the second meeting. Remember, “process” refers to establishing the operating agreements, including meetings, decision-making, and information-sharing. It’s the job of the change team leader to make sure those agreements are carried through.

Organization

Generally, the main organizational element to be aware of in achieving this goal is cultural: your organization’s current culture may or may not support this kind of approach to change. For example, if your culture is very fast-paced and not planful, you might get some resistance (even from the team members themselves) to having these foundational meetings—or even to having a defined change team at all. However, if your culture is very top-down and traditional, team members who aren’t senior leaders may have a hard time believing that they’re being given the freedom and responsibility to plan the change—and they may start by waiting to be told what to do.

If you think there may be cultural impediments to having this change team operate in the ways that will be necessary in order to be successful, build that conversation into the first few meetings, acknowledging those cultural realities, and encouraging the team to discuss what they may need to do (e.g., have conversations with their direct bosses, or ask people from the leadership team to do that; be aware of and address their own limiting assumptions; consciously find new ways to work together) in order not to be blocked by those cultural impediments. You’ll want to build the needed cultural shifts into the change plan; we’ll talk about that more when we get to the third goal in this step.

Let’s see how the folks at Moment are working through this part of Step 3:

Rachel starts the meeting right on time, just as Rajiv slides into his seat muttering an apology.

“Good morning, core change team,” she says, looking around at everyone. The newly defined change team is all present: Rajiv, the CTO; Steven, the CFO, and his financial systems person, Joy; Gina, the head of HR; and Carolyn, the GM of Stamford and White Plains, who is there to represent all the GMs. The final member of the team is Moment’s newly hired VP of marketing, Aliya. “What remaining issues or questions do you have from our first two meetings?” Everyone shakes their head, says, “I’m good,” or gives a thumbs-up.

Rachel nods. “Excellent. I thought you guys did a great job of finding your footing in those meetings.” She smiles. “Where are you all in your own change arcs?”

Steven responds first. “I’m well on toward seeing this all as potentially rewarding and normal,” he says. “But it still seems difficult.”

Freed by his honesty, others weigh in, and Rachel just listens. After everyone has spoken, Rachel summarizes: “So, it seems like those of you who were part of the leadership team, and have been thinking about this for a while, are generally further through your own change arc than those of you who are newly part of this team, which makes complete sense, but that all of you feel you’re well along in moving through your mindset shift. Does that summarize it fairly well?”

People nod or say yes. “Whatever I can do to help you keep making that shift—information, stories, or experiences—that’s part of why I’m here,” Rachel says.

Joy says, “Can you just follow me around all day and remind me what’s on the other side of this?” Everyone laughs.

Rachel turns to Steven. “As team leader, you’re going to get us started identifying other key stakeholders in the organization and figuring out how to best mobilize their support, right?”

“Right,” Steven says, standing as Rachel sits down. “But first, let’s talk about our change project sponsor . . . ”

——————GOAL #2——————

Identify Stakeholders and Mobilize Their Support

Leaders and Individuals

Here’s a simple way to think about the key stakeholders of a change: they’re the people whose lack of support for the change can keep the change from happening. You may be thinking, But isn’t everyone a stake-holder? If the Moment employees don’t adopt the changes, they’ll fail. And you’re right: that’s why all of Step 4 is devoted to leading everyone in the organization through the change. Unless most or all of the employees adopt the new ways of operating, the change won’t be successful.

In Step 3, though, you need to identify those stakeholders who are key to initiating the proposed change. For example, in the case of the company mentioned earlier that’s planning on changing its core production process, if the union steward isn’t on board with the change, she or he could create tremendous obstacles to involving union members in the change. Without the support of these key stakeholders you won’t get to the point where employees have the chance to decide whether or not to adopt the change! In other words, you’re looking for the people whose resistance could block the change even before it happens—and whose support can make it possible.

The Most Important Stakeholder: The Sponsor or Champion

Before discussing all the key stakeholders, let’s talk about the change sponsor or champion. In any change, the sponsor is the most senior face of the change to the organization. The sponsor is often the CEO but sometimes can be someone else in the C-suite. At Moment Jewelry, for instance, everyone agrees that Jade is the sponsor. She is passionate about the need for change, sees the postchange future clearly, and is articulate and consistent in talking about how important it is for the organization to get there. She isn’t a part of the core change team, but that team—especially Steven, the leader—will look to her for big-picture support, and the team will bounce key decisions off of her. They know that Jade is completely committed to the change and will do everything in her power to free up the resources and focus needed to make it successful.

Jade is a great example of all the necessary characteristics of the change sponsor:

• Deeply committed to the change

• Articulate about the need for change and how to achieve it

• Takes responsibility for supporting the change team’s success

• Has considerable power and influence in the organization

• Willing to be the face of the change to the organization—and has credibility with employees and outside stakeholders to play that role

• Balances their own passion for the change with an understanding of the change arc and that people need to go through that individually

In fact, it would be fair to say that the change sponsor—especially for a large, complex, and difficult change—needs to be a leader who is farsighted, passionate, courageous, wise, generous, and trustworthy.

Identifying the Other Stakeholders

In large organizations and especially with very complex changes, the most senior leaders in the organization—the C-suite and their direct reports—probably will not be members of the core change team: the change team is the working team that plans the change and transition and then project manages them through to completion. For a number of the change team members, their role on the core team may actually be their “day job” for weeks or months. Generally, the C-suite leaders will need to keep running the organization while the change is being planned and executed, rather than being working members of the change team. However, some of these senior leaders will almost certainly be key stakeholders. When trying to identify the key stakeholders for a change, three questions will serve you well:

• Which leaders’ areas of responsibility will be most impacted by the change?

• Which leaders will need to change the most?

• Who could most negatively impact the change, even if they’re not directly affected?

James is a good example of a key stakeholder at Moment. You may remember that their change involves both integrating online sales and social media marketing into their business model and moving “to a single financial system that includes a streamlined order-to-cash process for both in-store and online sales.” You might also remember that James, who is the GM of the Danbury and Waterbury store locations, runs his stores on a different financial system than the rest of the company. His stores will be more impacted by the financial systems part of the change than any of the other stores. He, personally, will have to change a lot—from a financial system with which he’s comfortable and has used for years, to a system that’s familiar to the other GMs and the finance folks, but to James is new and unknown.

When the Moment change team asks the three questions above, James immediately surfaces as a key stakeholder. His function will be deeply impacted, and he’ll have to change significantly. And he is also a good example of how a change can be blocked by a key stakeholder. If he drags his feet on changing his own behavior, or doesn’t support and encourage his on-site store managers, Nayla and John, to work closely with Steven and Joy in finance, it will be much more difficult to create a future where “the systems and processes that support the buying experience are seamless across stores and platforms.”

It’s also important not to forget those stakeholders who only fall into the “question 3” category—that is, those who aren’t strongly impacted and may not need to change much themselves but who could impede the change. For example, sometimes functions like legal, regulatory, or internal audit may have a lot of power in the organization, and they may be more focused on protecting against risk as opposed to helping the company grow or change. Folks like this may not be much impacted by a change but could get in the way of its success—either by speaking negatively about the change in public or by trying to convince others that it’s not a good idea. Be sure to recognize and include these people in your stakeholder analysis and then work to mobilize their support.

Mobilizing Support: Stakeholder Analysis

Once the change team has a good sense of the key stakeholders—those leaders who will be most impacted and of whom the greatest changes will be required—it’s important to get a sense of where those people will likely be starting from relative to the change, so you can incorporate gaining their support into your planning. A stakeholder analysis template can be a simple way to understand and visualize that information (Figure 11).

Here’s how you can use this template:

1. Note the stakeholder’s name and function in the left-hand column.

2. Then note (shown here with an “0”) where you believe the person is starting from right now in terms of their support for the change: strongly against, moderately against, neutral, moderately supportive, or strongly supportive.

3. Now, note where you believe this person’s support for the change needs to be in order to assure the change isn’t blocked or impeded (shown here with an “X”). Generally speaking, if you’ve identified your stakeholders correctly, they will all need to be at least neutral to moderately supportive for the change to be successful.

4. Then, in the space below, note what you believe the stakeholder’s key concerns are. Note whether each concern is primarily mindset (arising from this person’s current belief that the change will be difficult, costly, and weird), behavioral/functional (arising from a perceived lack of needed skills, tools, or resources), or organizational (arising from the sense that existing systems, structures, or culture will make the change difficult or impossible). It’s useful to make this distinction whenever possible, because it provides you with important insight about what might be needed to address the concern. Addressing mindset concerns generally requires supporting people through their change arc, by helping them make their own internal mental and emotional shifts. Resolving behavioral/ functional concerns most often involves offering practical solutions like training, equipment, or process clarity. And resolving organizational concerns could involve either including more organizational elements in the scope of change—or providing information, stories, and experience to help the stakeholder see that their concerns are unnecessary or are being addressed.

FIGURE 11. Stakeholder analysis

You may not know their concerns at this point, or you may have some initial hypotheses. You’ll be able to evolve this part of your analysis as you connect with your stakeholders and support them through their personal change arc.

Stakeholder Engagement

Once the team has identified the key stakeholders, noted where they’re starting from and where they need to end up in terms of their support for the change, and finally have taken a first pass at noting the concerns of those stakeholders who aren’t now supportive of the change, the team is ready to decide on and incorporate the process of engaging the stake-holders into their overall change planning.

It’s important to do this in an organized way. It can be tempting to be ad hoc about this—especially in smaller organizations—to say, for example, “Oh, I know Joe—I’ll just go talk to him. He’ll be cool about this when I explain what’s happening.” But remember, you don’t actually yet know what’s really happening—you haven’t yet made the change plan. You might tell Joe one thing, and then he’ll hear something else from another member of the change team later and feel even more confused and unsettled. It’s better to have a plan . . . even if the plan doesn’t always go to plan. As soon as you have the project charter, you can begin to talk with stakeholders—we’ll talk about that in just a bit.

Organization

As with creating the change team, any organizational impediments here are most likely cultural. For example, in some cultures that value talk over action, it may be difficult to find a sponsor who is able and willing to play the role in a substantive way: senior leaders may be happy to give lip service publicly but won’t go to bat for the team to make sure they have what they need to be successful. The organization might be okay with that version of sponsor (it may be what they’re used to and expect), but the team will need something more. In that case, you may end up with a “real” sponsor, a true champion—often someone a few layers down in the organization who sees how necessary the change is and has built actual support for it internally, and to whom people look as a true leader. That actual sponsor can then work closely with the “public sponsor”—the more senior leader whom everyone may expect to be the sponsor but who will be less active in that role—to agree on the kind of support that’s needed and which of them will offer it.

Cultures that are “too nice” may present another difficulty at this point. Stakeholders may be reluctant to share their concerns out loud, so it may be hard to know whether they’re supportive of the change, and—if not—why not. In this situation, as mentioned earlier, part of your planning will need to focus on how to catalyze the cultural shifts needed to change your organization in the ways you’ve envisioned.

——————GOAL #3——————

Build the Change Plan

Leaders

This is the key tipping point in your change effort: the change team members, and especially the team leader, should by now have taken responsibility for being the key drivers of the change (along with the project sponsor, and often a full-time project manager, if the change is large and complex). They are about to draw together all the threads of what they know and what has been agreed upon so far, and create an overall, practical plan for the change. This may seem like a daunting task—especially if the change is complex and the organization is large. You may remember that this is where the Old Sailor froze, wrapping himself in his shawl and lying on the beach waiting to be saved.

One way to keep yourself (and your change team) from becoming overwhelmed at this point is to remember that the nuts and bolts of navigating through even the most complex, far-reaching change or series of changes is a project. And we humans have figured out a lot of important things about how to manage projects well. I’m going to share some key project management tools and approaches you can use in planning any change, large or small. I hope this will be helpful in giving you a sense of how to approach making your change plan. Remember, though, if you’re planning any change that’s complex enough to require a change team, make sure that at least one person on the change team has project management training and experience. It will save you untold hours of reinventing the wheel (people have already figured this stuff out) and vastly increase your chances of success (there’s a reason that people get trained in project management).

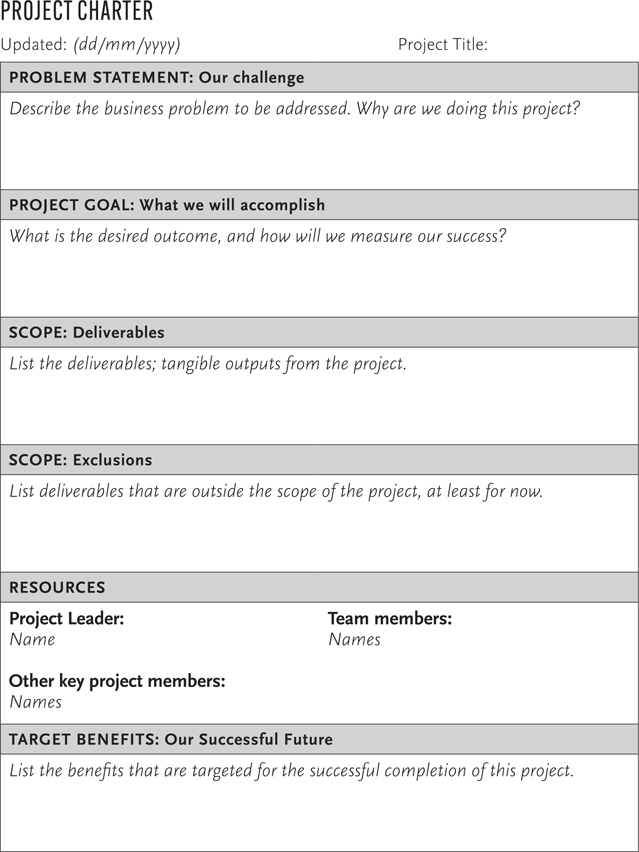

The Project Charter

Practitioners of project management think of this as their foundational tool. The project charter is a single sheet that captures the essential information about a project to be managed. Take a look at our standard project charter template (Figure 12).

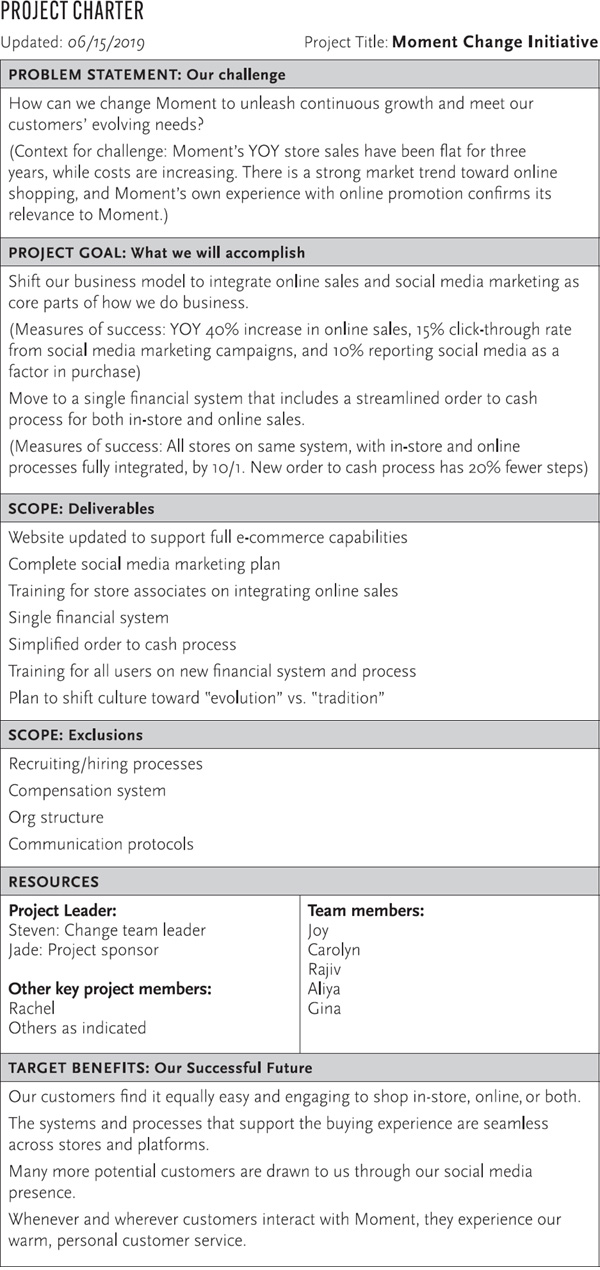

This template becomes the perfect repository for the clarity you’ve already established—in Steps 1 and 2 of the change model—about what, why, what-it-will-look-like, and the change team. You can also see how the Moment folks have completed their project charter (Figure 13).

FIGURE 12. Project charter

FIGURE 13. Moment Jewelry project charter

The Problem Statement is Moment’s original challenge (plus a little context for why that’s their challenge). The Project Goal is their “what”—both their definition of the change and how they’ve decided to measure their success. The Scope—deliverables and exclusions—are just as they have defined them in working through Step 2 of the process (and remember, this is an initial list—they’ll get clearer about it as they plan and work the change). The Target Benefits are their what-it-will-look-like—that is, the vision they defined in Step 2. And in the Resources section they’ve noted the change leader and team; the project sponsor, Jade; Rachel, their change consultant; and they will add others as appropriate. Having this core information all in one place serves a number of purposes. First, it’s a clear agreement among everyone who is involved in planning the change: it makes sure that everyone is literally working off the same page. The project charter is also a great starting point for conversations with stakeholders (those will start happening now); it provides them with key information in a simple format and, again, makes sure everyone is hearing the same thing. Finally, along with the elevator pitch, this document provides a wonderful foundation for all the communications to the larger organization that will happen in Step 4.

Using the Project Charter to Engage Stakeholders

I told you we’d come back to stakeholder engagement after we talked about the project charter, so here we are. This is a great time to focus with the change team on how and when to engage your key stakeholders; you want them to be as supportive of the change as possible as early on as possible. Now that you have the project charter, you can use that with the stakeholders to begin to move them through their own change arc, by clarifying for them what will be happening and why. You can also use the project charter to show them how you’ll be addressing their concerns. For example, James at Moment was pleased to see that “training for all users on new financial system and process” was a deliverable in their project charter—he was a little worried that his folks would be expected to get up to speed on those things by themselves.

Here’s a simple approach for beginning to engage your stakeholders at this point:

• Buddy up. “Assign” each stakeholder to someone on the change team (or perhaps to the project sponsor, for the most senior stake-holders). Pick someone who has a positive, respectful relationship with the stakeholder, and who will understand and be able to address their concerns—and represent those concerns back to the change team.

• Agree on the approach. All of the change team members who will act as stakeholder buddies should agree on what the core message should be, how they’ll walk their stakeholder through the project charter, how they’ll gather the person’s feedback and bring it back to the group, and how they’ll stay in touch and support their stake-holder’s movement toward “supportive.” It’s often useful to have a change team meeting focused on clarifying these things.

• Stay connected. Once the change team “buddies” have had their initial conversations, be sure to make time in the change team meetings to debrief and decide how to keep the stakeholders looped in and moving in the right direction.

The Magical WBS

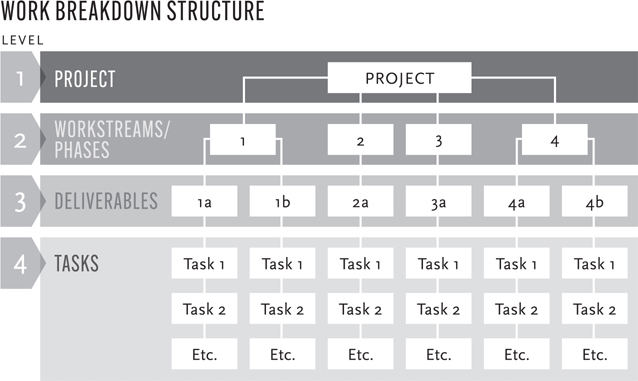

Okay. So now you’ve got a project charter for your change. What’s next? This is where your change team rolls up their sleeves and starts making the actual plan for the change. I want to introduce another tool beloved by project managers everywhere: the WBS (Work Breakdown Structure) (Figure 14). It’s a great way to unpack the work that will need to be done in order to make the change or changes you’ve envisioned.

Level 1: Project. This level can simply be the change itself (as in the previous example of Moment Jewelry’s project charter). However, for an extremely complex or long-range change, you can use this project level to break the change into manageable pieces. For example, let’s say a multinational media company is changing their core distribution and commercialization process (D&C), and the change is going to require very different work in each geographical area because the business units are in varying states of evolution. The company might therefore want to have a project (and therefore a separate WBS) for each geography—for example, “D&C transformation EMEA,” “D&C transformation NorthAm,” “D&C transformation LatAm,” and so on.

Level 2: Workstreams/Phases. This is where you begin to divide up the work to be done. For fairly simple changes, or changes that start in one part of the organization before rolling out to others, it may make the most sense for the work to be chronological, divided into phases. The situation described in Chapter 7—the commercial real estate company that’s updating their brand—is a good example of this. Their work-streams might be “analyze current state,” “redesign brand,” “develop brand materials,” “launch new brand,” and “evaluate impact.” Where a change is more complex, though, or involves different parts of the organization simultaneously doing work on different aspects of the change, it probably makes sense for the workstreams to be functional. In Moment’s change, for instance, the change team decides there will be separate workstreams for finance, technology, marketing, and people.

FIGURE 14. Work breakdown structure

Level 3: Deliverables. Once you’ve divided the project into the appropriate workstreams or phases, you’ll allocate the agreed-upon deliverables among them. If you’ve created the appropriate workstreams or phases for your project, this should be fairly self-evident. In fact, if you find it difficult or confusing to assign your deliverables to your workstreams or phases, that may be a good indication that you haven’t divided your project well. Using Moment as an example, all the deliverables listed on the project charter can be easily assigned to one of the four workstreams noted above: “single financial system” and “simplified order to cash process” fall under the finance workstream; “update website to support full e-commerce capabilities” is under the technology workstream; “complete social media marketing plan” is under marketing. The change team decides that the two training deliverables (for integrated sales and for the financial systems and process) fall under the people workstream, as does “plan to shift culture toward ‘evolution vs. tradition.’” Completing this part of the process can also help tease out deliverables you may have forgotten in earlier conversations. As our friends at Moment are creating their WBS, Rajiv realizes that one deliverable they’ve forgotten is connecting the in-store and online point-of-sale purchase “carts”—so that someone can select something in-store and finish the purchase at home, or vice versa (that is, select something at home and go into the store to buy it). So they add that deliverable to their technology workstream.

Once you’re clear on which deliverables will fall under which work-streams, you’ll agree on owners for each deliverable. As you’re deciding this, it’s important to clarify that the owner is the person responsible for delivering the deliverable. That person will not do all the tasks; they are responsible for assuring the tasks get done. I often use the example of Tom Sawyer here: when Aunt Sally told him to whitewash the fence, he convinced other people to do the work—and so fulfilled his responsibility of delivering a newly whitewashed fence. In fact, we often call the owner of a deliverable the “Tom Sawyer”—it’s a lighthearted way to remind everyone that this is the person responsible for making sure the “fence gets whitewashed”—not for doing all the whitewashing alone. For example, even though Gina, the head of HR for Moment, might be the owner for the two training deliverables, she’ll be relying heavily on Steven and his team for designing the content of the financial training, and probably for conducting the training when it’s complete. And she’ll be working in the same way with Rajiv for the design and delivery of the integrated selling training. Think of the Tom Sawyer as the person who is on the hook for the deliverable being completed well and on time—and making sure they clarify and arrange the support or resources they’ll need to make that happen.

Level 4: Tasks. This task level is where the change team gets down to the nitty-gritty of what, who, and when. This is, if you will, the guts of the plan: once you’ve named, organized, and assigned the key tasks, you have a change plan.

Completing the WBS as a Team

We suggest the change team do the entire WBS process collaboratively. Using Post-it notes and a big wall (or virtual Post-its on a virtual wall, if you’re not in the same physical location), work together to divide the change project into workstreams, then allocate the deliverables under the work streams, adding any deliverables you may have missed during earlier conversations.

Now you’re ready to assign owners for the deliverables. To avoid confusion, it’s important to have just one Tom Sawyer per deliverable—remember, this person is not going to be doing all the tasks alone (many of the tasks will be done by or with others). The owner is the person who is responsible for making sure the tasks get accomplished in order to complete the deliverable: if that responsibility rests ultimately with a single person, it’s much more likely to happen. Generally, a deliverable’s owner should be the person within whose job description the deliverable lives, and who has the experience and bandwidth to oversee the completion of it. That person might also decide to assign the deliverable to someone on his or her staff who has the necessary expertise, bandwidth, and interest. For example, in our Moment change effort, Steven, the CFO, agrees to be the owner for the “simplified order-to-cash process” deliverable, and he asks Joy, his financial systems person, to be the owner for the “single financial system” deliverable.

Once you’ve agreed on the owner for every deliverable, ask each owner to make a Post-it for each of the tasks that will need to be completed in their deliverable. This is just a first step; they don’t yet need to think about how the tasks will be sequenced, or to include task owners or due dates for the tasks. Each Post-it should describe a single task in a verb-noun format—for instance, “map current order-to-cash process,” as opposed to simply a noun, such as “current process.” This allows everyone on the team to understand what the task actually entails, and the task owner—once that person is assigned—to know what they’re agreeing to do in taking ownership for it. Once the Post-its are complete, have the deliverable owners put them on the wall (physical or virtual) under their specific deliverable—don’t worry about putting them in chronological order yet. Have the owner of the first deliverable read their Post-it notes aloud. The rest of the group can then ask for clarity where needed and suggest any missing tasks—this will help the deliverable owner improve and clarify their planning. When the tasks under the first deliverable have been reviewed and revised, go on to the second deliverable and so on, until all the tasks under each deliverable seem reasonably complete and clear.

Once you’ve done this, the deliverable owners will write the name of a proposed task owner on each of the task Post-its under their deliverables. The task owners should be people who have the skills, bandwidth, and interest necessary to complete the task. When every task has a proposed owner, the change team should review all of them together, to make sure there’s agreement—and also to make sure that the “asks” are realistic—and if not, how to make them so. For instance, if a task owner is someone outside the organization, note any added expense this will entail (to be added later to the project budget). If they are people not on the change team (as will often be the case), decide who will explain the change and their proposed part in it and invite them to own the task. If one person is the owner of a number of tasks, and the time involved will make it difficult for them to complete their day job, decide how their regular responsibilities will be accomplished during the change.

There’s more work to be done to turn this overall plan into a project schedule, but if you’ve come this far, you’ve done a better job than many organizations do in planning for change. Let’s check in with Moment to see how they’re doing at this stage:

The Moment change team has done amazing work in a short period of time. Rachel’s impressed that it’s only taken them two meetings to create their project charter, identify the workstreams and deliverables (with owners) for their change project, and now, to identify the tasks under the deliverables and assign them owners. The team has been focused and very mutually supportive.

Suddenly Rachel notices that Rajiv, ordinarily serious and quiet, is giggling helplessly. He simply points at the wall when Aliya asks him what’s up. Rachel looks at the board and notices that Joy has added a few new Post-its, in red, to the tasks under her deliverable of “single financial system,” reading things like, “Take a long lunch to avoid telling James how different this is going to be,” and “Curse fluently when the computer in Danbury won’t reboot the new system.” Steven, her boss, shakes his head in mock dismay, grinning.

“What?” Joy says, eyebrows raised and palms up. “Those things are certainly going to happen—and I’m responsible. We can’t leave them out!”

Now everybody laughs, and Rajiv quickly puts a couple of his own pretend Post-its under his e-commerce deliverable: “Take a vacation when the website platform won’t do what we need it to do,” and “Explain e-commerce for the seventh time to an employee who doesn’t use a computer at home.”

Rachel lets the joke run for a while—the team has been working hard, and they need some playing around time—then asks, “All right, gang, time to regroup?”

After some exaggerated and good-natured grumbling, the team refocuses on the task at hand. And they decide to give many of the “joke” Post-its to Gina to save—they realize that these provide actual insight into their own and others’ difficulties in going through the proposed change or mindset shift part of the change arc.

“Between now and the next meeting, we’re going to do some individual work,” Rachel says. “Each of you as deliverable owners will need to sequence your tasks, so we’re going to be looking at timing and dependencies. Then we’ll come back together and organize what you’ve come up with into an overall project schedule. At which point we’ll have a pretty fully-baked change plan.”

Carolyn, usually quiet and dignified, smiles and says, “Yay, us.” Everyone nods or applauds, and they settle down to hear about how to sequence and time their tasks.

One More Step: Scheduling

Now you have all the pieces of your change plan; you just need to put them in the proper order. It generally works best for the deliverable owners to do the first draft of the scheduling for the tasks within their deliverables, then bring the team back together to make sure all of your efforts will be aligned. So here’s what each deliverable owner will do:

• Put the tasks roughly in order. To do this, think about dependencies. As you look to see what should be the first task under a deliverable, ask “What do I need to do before I can do anything else?” Often these are tasks having to do with assessing the current state. For example, Steven, who is the owner for “simplified order-to-cash process,” might decide that “map existing order-to-cash process” is her first task. A few tasks may not have obvious dependencies on any other tasks, so you can slot them as you see fit.

• Note about how long you think each task will take. Take some time to think through the complexity of the task, whether it can be completed independently by its own owner or will require collaboration or input from others, and even what you know about the owner’s work pace. You want to balance forward movement with realistic expectations.

• Break up large or long-term tasks. If you find that a task will take longer than a few weeks, it’s generally best to break it into subtasks, both for clarity and to provide regular checkpoints.

• Make notes on dependencies. As you’re thinking through the previous steps, you’ll find you’re making assumptions about why your tasks will need to be done in a particular order—and you may realize that completing some of your deliverable’s tasks will depend upon tasks in other deliverables being completed. Make notes so you can bring this up when the team comes back together to create the overall project schedule.

Bringing It All Together

Now you’ll bring together the change team once again, and all the deliverable owners will post (either physically or virtually) the work they’ve just done, so the tasks are in order, with time estimates, and larger tasks broken into subtasks and connected by lines. This is where having moveable Post-its (again, either physical or virtual) is very helpful—you’re likely to do a lot of shifting around.

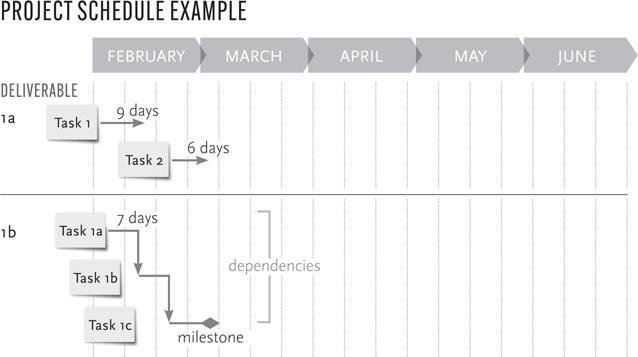

Let’s say you’re meeting virtually and using a virtual white board (there are many great platforms for doing this—we like using Miro to have more visual and moveable frames, but you can also use more traditional planning platforms like Smartsheet).29 Across the top of the board, divide it into a timeline. Now divide the board under the timeline into horizontal lanes, one for each deliverable, and ask the deliverable owners to put their task Post-its in date order from left to right in their lane. Have them draw a line after each Post-it to show the task’s duration, and draw “dependency” lines to show which tasks are connected. Have them put a milestone shape at the date when all the subtasks in a task are completed, and a big final milestone shape where all the tasks in their deliverable will be done. Here’s how that will look as the group starts to work (Figure 15).

FIGURE 15. Project schedule

Once all the tasks on the whiteboard are in order, with duration and dependencies shown, everyone can review it together. As a group, look for and address the following:

• Dependencies between deliverables. This is a chance for everyone to realize, “Oh, wait—we won’t be able to do Task 3 in Deliverable A until we’ve completed Task 2 in Deliverable B”—and then reorder or move the timing of tasks to reflect those dependencies.

• Unrealistic demands on individuals. Looking at the project schedule, you may realize, for instance, that the way you have tasks scheduled will require one group of employees to be designing a new product while communicating something to the organization and getting trained on a new process. You’ll need to spread out those tasks or make others responsible for some of them.

• Nonchange demands. Even though the change is critical (or you wouldn’t be making it), it’s not the only thing that’s happening in your organization. You may realize, for instance, that your timeline shows the finance group heavily involved in completing change tasks right when they’re going to need to do the year-end close. You’ll need to move those tasks to before or after year-end—or find someone else to do them.

• Resource constraints. The last consideration is, of course, do we have the money for this? The change team will generally have a finance person (even if the change isn’t directly finance-related), who will be creating a budget for the change effort while you’re creating your change plan. As you review your plan, look for more cost-effective ways to allocate time and people resources. If, for instance, by moving a task back two weeks, you can take advantage of an existing software license instead of paying for a new one, or you can work with a great internal person instead of having to bring on a contractor—move that task.

I could keep going down this project scheduling path . . . but I’ll stop here. I hope this has provided you with some good core tools and insights for making your change plan. As I said before, be sure to have someone on the change team who is experienced and comfortable with the art of project management to support and guide you through this part of the change process.

Individuals

The folks in the organization you’ve been talking to and bouncing things off of in Steps 1 and 2 will probably be those you go to as subject matter experts and task owners in this part of Step 3. Since they’re in the know and will probably already have moved through the mindset shift part of their own change arc, they will generally be ready to help.

Look for ways to include some of the key stakeholders who aren’t on the change team in the creation of the plan. Remember to first help them start to move through their own change arc: use the project charter to answer their proposed change questions and catalyze their mindset shift as needed, then ask for their support or involvement in whatever ways seem best for them and for the project. This can be a powerful and practical way to move them from “against” or neutral to supportive by providing the personal experience that will help them see the change as easy, rewarding, and potentially normal.

Organization

In making the change plan, you are identifying what needs to change in the organization—structurally, systemically, and culturally—in order for the change to take place, so organization will be at the heart of the change plan. However, as you’re agreeing on the deliverables, be sure that you look for and include any underlying organizational impediments that may need to be addressed if the change is to be successful. For instance, our friends at Moment realize that in addition to the systemic changes they’re making in how sales happen, fully integrating both online sales and social marketing into how they do business, they also need to shift the company’s strong cultural value around “tradition.” Part of their change plan involves building and implementing an approach to revising that value to one of “evolution,” so that the new integrated approach to sales and marketing can be fully embraced and sustained. This also helps ensure that the company will be more open to the need for ongoing future change.

——————GOAL #4——————

Assessing Organizational Readiness

Even though this is the final goal in this “building the change” step, you’ll find you’ve been informally assessing readiness since the beginning of Step 1 of the five-step change model. You’ll have noted which members of the leadership team seem open to and enthusiastic about the change, and you’ll have been thinking about whether people have the skills they need to operate in the new ways the change will require. The stakeholder analysis you did earlier, when you noted whether each key stakeholder was starting against, neutral, or supportive of the change—and why—was, in a sense, your initial assessment of their readiness.

You also probably built some readiness assessment into your plan. For instance, in the Moment change plan, Steven’s first task, in her deliverable of “simplified order-to-cash process” is “map existing order-to-cash process.” Gina’s first task in her deliverable of “plan to shift culture toward evolution vs. tradition,” is “conduct an employee pulse check on existing and proposed cultural values.” Doing both of those things will provide a lot of important information about how big the gap is between the current reality in those areas and what’s needed to make the change. But you’ll probably still be missing some needed understanding about how ready the organization is to make this change, so I want to share some additional ideas for getting clear about how ready the organization, your leaders, and individual employees are to make this change.

Leaders

Once you have your change plan, vet it with the senior leadership team, to make sure you have their support before you move to Step 4 of leading the organization through the transition. Use this meeting to assess the leaders’ readiness for change. The best way to do this is to set the expectation that this meeting will be more a conversation and less a presentation. To make that more likely, have the change team leader and the sponsor share the plan with the senior team—as opposed to the whole change team (that tends to make it more “presentation-like”). An even better approach, if possible, to really assess leader readiness for change, is to have the change leader and sponsor begin by having individual meetings with senior leadership—starting with the CEO—rather than unveiling the plan to the whole group at once.

Socializing the plan like this, individually first, gives you a chance to assess each person’s readiness and address each person’s concerns. This is especially useful if you suspect that different leaders may be in very different stages of readiness for the change. Sharing the plan individually not only gives you a better chance to assess readiness, it provides a way to help each leader feel heard and included and to tweak the plan based on what you hear. This way, when you do share the plan with the whole senior team, you’re more likely to get their support and buy-in. You might also want to do some surveying of the senior leadership team (and other key stakeholders) after you’ve shared the plan with them, asking them how ready they believe the employees and the organization are for the change overall (perhaps on a scale of 1–5, where 1 is “not at all ready” and 5 is “ready now”), and then where they believe the biggest gaps will be culturally, structurally, and systemically. What you hear may help you improve your plan, by adding tasks for skill development, additional resources, or more time for helping people through their individual change arc.

Individuals

As you build the change plan, you’ll probably be going back to those folks you’ve already been relying on as resources throughout Steps 1 and 2. They understand the change and—hopefully—have a good sense of the organization. You can ask them the same question you’ve asked the leaders: “How ready do you think the employees and the organization are overall for this change?” Then you can dig into what they see as being key gaps. Finally, you can do surveys or focus grouping on subsets of the population that will be most affected by aspects of the change. For instance, Steven at Moment may decide to get together with a small group of senior employees from the Danbury and Waterbury stores, to find out what they think will be hardest and easiest about moving to a common financial system.

Organization

As you’re building the plan, notice any assumptions you may be making about structures, systems, or cultural expectations—organizational elements you believe are in place to build upon in order to make the change. For example, for the commercial real estate company that was updating its brand, one of their deliverables was the following: “A phased plan for revising all electronic uses of the brand throughout the organization (to include logos to media outlets, sales decks, fact sheets, proposal templates, and email signatures).” The change team assumed there was an existing process they could build on for making sure that everyone was using the same version of the company branding. But when they got curious and asked if that was so, they found that didn’t exist. Based on that assessment, the change team added a new deliverable: “Establish an agreed-upon process for assuring that everyone in the organization has access to only the most current version of the company branding.”

This is a way to target your assessment. As you’re building your plan, question your own and your teammates’ assumptions. Every place the plan contains a task that assumes an underlying system, structure, or cultural expectation is in place, ask yourself, Does that really exist and is it now functional? The answer may be “yes,” in which case—whew! But if you think the answer may be “no,” or you’re not really sure, that’s a great place to dig in and do some current state assessment.