TEN

To the Future

At some point, all this preparation and planning, all the effort and angst, will have finally paid off. With some changes there’s a clear demarcation of before and after: a specific day and hour when you move from old reality to new. Having a baby, taking a new job, closing an office. Most changes, though, are less black and white than that. For our friends at Moment Jewelry, I suspect it will be hard to pinpoint the precise moment when the in-store staff are comfortable and fluent in the new reality of integrated in-person and online selling. Or when everyone in the company fully accepts and adopts the new order-to-cash system. Instead, there will be a change team meeting where everyone realizes that all the tasks on the change and transition plans are completed except for some final minor “to-dos” and that the new systems and ways of operating have become, for most people in the organization, reasonably easy, rewarding, and normal.

So, what then? This stage is where, all too often, we congratulate ourselves, the change team dissolves, and we turn our attention to other pressing matters (of which there is never a shortage). And sometimes, by sheer luck, that turns out okay. The change and transition were planned and executed well enough that the new reality keeps rolling along—no harm, no foul. Far more often, though, abandoning the change at this point doesn’t turn out so well. With no focus on monitoring ongoing progress and making adjustments, the change can easily sputter to a halt, half accomplished. If there are overall unaddressed organizational impediments—ways in which your systems, structures, or culture are antichange in a larger sense—this change and future changes may be doomed to failure, despite your good planning and preparation. I’ve even seen reasonably well-planned and well-executed changes be completely reversed, when the opposing weight of overcomplicated, disconnected, or nonexistent systems or structures or an unsupportive culture makes it too difficult or costly, or makes it seem too “weird” to continue operating in the new ways.

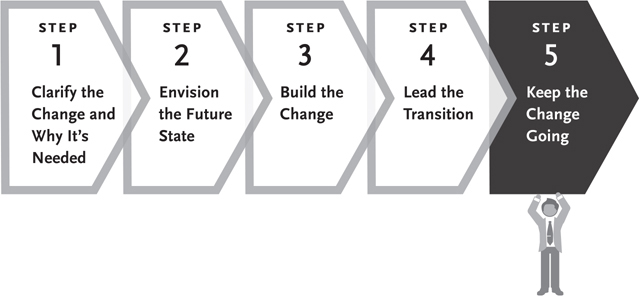

FIGURE 19. The five-step change model: STEP 5

Think of Step 5 in the change model as your chance to make sure that the change you are implementing is successful and—more important—to set yourself up for success with the changes yet to come (Figure 19). In other words, it’s an opportunity to make leaders, individuals, and the organization itself more change-capable. This step answers the question, How will the change—and change itself—become business as usual? The three goals of this step—monitor and report progress, institutionalize ongoing adjustments, and make systems/processes, structures, and culture more change-capable—support you to answer that question.

The change team at Moment is gathered in the conference room, but they’re not particularly focused: Gina and Joy are talking about the training on the new financial system, which just finished last week; Carolyn is asking Rajiv about a minor technical problem some of the store staff are having getting online purchases to come up when the customer has also bought items in-store; Jade, who has joined this meeting, is going over the new social media marketing plans with Aliya.

Steven stands at the front of the room, checking off completed tasks on the change and transition plans. “Hey guys,” he says suddenly. Everybody stops talking and turns to face Steven, who shakes his head, looking bemused. “We’re done.”

“Wait,” Rajiv says. “What do you mean, ‘done’?”

“Well,” Steven responds, “unless I’m missing something, all of our deliverables are pretty much delivered.”

Everyone is silent for a long moment. Finally, Joy says, “Congratulations?” They all laugh.

“Absolutely congratulations!” Jade says. “This is amazing. Bravo to all of you and to the whole organization.” The group dissolves into happy chatter—about how hard it’s been, how people in the organization have really stepped up, how tired they are, how much they like the website . . .

At last, Carolyn asks, “So . . . what now?”

“Now,” Steven says, “we spend a few minutes high-fiving ourselves, and then we get ready for Step 5. Remember Step 5? We have to make sure this keeps going.”

Everyone nods and, led by Joy, the change team agrees to go out for a celebratory drink to end this meeting. They decide to jump into Step 5 at their next meeting.

Jade pulls Steven aside on the way out of the conference room. “Let’s invite Rachel back to run the first Step 5 meeting—we haven’t ever had to sustain a big change . . . and we’re not great at using data to monitor progress.”

“I completely agree,” Steven says. “And you and I both know that there are still some organization-level impediments to change—things we’ve seen that will make it harder to sustain these changes and will get in the way of future changes. Gina has done an amazing job Tom Sawyering the cultural shift, and I think our structures are okay, but there are definitely systemic problems we need to figure out how to address—for this change and whatever the next one will be.”

Sighing, Jade nods. “I guess change really is nonstop these days.”

“Yes,” Steven agrees, as he closes the conference room door behind them. “I figure we can either bitch and moan about it—or learn how to be good at it.”

When that magical day arrives, as it did for the folks at Moment, and you realize that your deliverables have been delivered, everyone on the change team is going to have to decide how to operate in this final phase. I encourage three shifts to set yourself up for success in Step 5:

1. Evolve your change team cadence. In this step the change team generally won’t have to meet as often or for as long. You might start with half as many meetings (for instance, if the change team has been meeting weekly, twice a month may work well). You might find that you need less time in your meetings than in earlier steps; if so, make them shorter. Meetings need to continue to feel and be productive.

2. Redefine team roles. Once the deliverables and tasks are completed, team members no longer have specific assigned roles. Rather than just let accountability drift, it’s best to create specific agreements about your new roles in step 5. For example, the Tom Sawyer for a particular workstream or deliverable might not be the best person to be in charge of monitoring progress and adjusting the approach if necessary. You may want to assign someone else to oversee that work. If you encounter new organizationwide efforts needed to make systems, structures, or your culture more change-capable, you’ll need to decide who will manage those efforts as well. It’s best not to assume that the team leader role will remain with the same person. There may be someone on the team who is better at and more motivated by the monitoring and ongoing improvement that is the focus of Step 5, as opposed to the planning and execution focus of Steps 3 and 4. Make sure that the change team leader for this step is best suited to this part of the process.

3. Be ready to make new plans. The plans you build in Step 5 probably won’t be as complex as the plans in Steps 3 and 4—but the planning chops you built in Step 3 and refined in Step 4 will definitely come in handy. For example, if your organization doesn’t already have good processes for collecting and reviewing data about the results of the change, and for institutionalizing adjustments, you’ll have to make plans to build those. If you find underlying systemic, structural, or cultural problems that need to be resolved in order to support this change long-term, and other changes that will arise, you’ll need to plan for those organizational changes. Being able to plan for both change and transition is a skill that will serve you in every aspect of your life.

——————GOAL #1——————

Monitor and Report Progress

Leaders

You may already be good at monitoring and reporting progress for ongoing initiatives, and if so, congratulations. In my experience, however, many leaders are not. It’s a Goldilocks problem: some leaders err on the side of too much monitoring and reporting; they spend so much time, money, and effort gathering, reviewing, and reporting on the data that they may not pull back the camera to see what’s most important and actually do something about it. Many more leaders spend far too little time monitoring and reporting: they either don’t have mechanisms for assessing whether their change efforts are working or don’t pay attention to those mechanisms.

I want you to be “just right” in this part of your change effort. I want your change team to have FIT (feasible, impactful, timely) ways to track and report the progress of your change. Fortunately, you don’t have to start from scratch: you can build on the measures of success you determined way back in Step 2. Now that you’ve implemented your change and transition plans, when you review your original measures of success, you may find that you missed some important elements. You may find that some of your measures either aren’t a good way to measure the success of the change (they don’t correlate with the outcomes you want) or that they are too difficult to measure. But even though they may need some revising, your initial measures of success are almost always a great place to start when you’re deciding how best to monitor and report on the success of your change going forward.

As you finalize your original measures, remember the key ideas in building measures of success from Chapter 7: leverage current practice, don’t bog yourself down, and pick your shots. In other words, insofar as possible, use measures and ways of reviewing them that already exist in the organization; don’t make the monitoring and reporting so cumbersome and time-consuming that it takes more effort than it’s worth (and more than anyone will actually put into it for the long term); and select a few most representative measures rather than trying to be exhaustive. You’ll be more successful if you use a dashboard approach.

Once you’ve agreed on your measures, determine when and how you’ll review/report what’s happening with those measures, and who will be responsible for making sure the change team has that information. For instance, once the change team at Moment had finalized the success measures they wanted to monitor, they agreed that Aliya would be the Tom Sawyer for the success measures relating to social media marketing and the customers’ views of the integration of in-store and online branding and support, and that Joy would take responsibility for the success measures around the financial system. Gina volunteered to own the monitoring and reporting on the success measures around the staff’s understanding and acceptance of the change. Rajiv took responsibility for the success measures around the efficacy of the website as an e-commerce platform and its integration into in-store sales. The four of them got together and proposed to the team that they spend one of their twice-monthly meetings to review and report on the measures, and decide what, if anything, needed to be done in response. The alternate meeting would focus on making any indicated adjustments (Goal #2—which we’ll talk about shortly).

Individuals

It’s good to let the organization know that you’re making these efforts. Generally speaking, employees assume that once a change has been made, senior leadership and the change team don’t really pay any attention to how it’s working, and whether further changes or adjustments may be needed. Sadly, they’re often right. So simply by sharing how you’re measuring success and that you’re measuring success, you can further support the acceptance of the change: you’re increasing people’s understanding (“Here’s how we’re going to make sure that we’re actually heading toward the future we’ve envisioned”) and clarifying and reinforcing priorities (“Yup, making these changes is still a priority and will help us achieve our other priorities”).

If you also include people in the data collection around these measures, you’re giving control. For example, Gina decided to create a simple quarterly online “pulse check” for employees to report their experience of the changes and provide feedback on needed improvements. The change team made those results a part of their monitoring and reporting, and let the organization know that. If you actually act on what you hear from them (again, we’ll talk about this further in Goal #2), you’re giving control and giving support.

Organization

Quite often, having problems in monitoring and reporting progress on your success measures is a function of underlying systemic problems in the organization. Let’s go back to our friends in the commercial real estate company who are changing their brand. One of their key measures for the success of the change was “Increased brand awareness and affection among owners of commercial real estate in their major markets.” The change team realized, when they got to Step 5, that their systems for gathering this data were different in every market—and ranged from haphazard and anecdotal in some markets to pretty rigorous in others.

Fortunately, once they saw this, the team put in place a simple plan to expand the best practices from the two regions that were doing it well to the other five regions. Within a few months they had a good system in place: all seven regions were gathering and reviewing the impact of the new branding on their core demographic segments. They realized that this system would support them being able to gauge the success of any future branding efforts or marketing campaigns.

——————GOAL #2——————

Institutionalize Ongoing Adjustments

Leaders

Developing a cadence of monitoring and reporting on the progress of the change is key to the long-term success of your change efforts. Don’t pat yourself on the back too soon, though: it’s all too easy to monitor and report progress and then not make the adjustments that your reporting tells you are necessary. Some leaders can talk themselves into a kind of self-congratulatory complacency at this point: “We’ve all done such a good job with this change,” they say to each other, “of course there are a few little bumps in the road, but that’s to be expected . . . no need to really address those, right?” And while they’re all agreeing with each other about how great everything is, the change effort can start to go off the rails. This is the time to be a fair witness. If one or more of your success measures aren’t being met, look very carefully at what’s happening. Don’t cherry pick the data, and don’t fall prey to confirmation bias. Don’t make excuses. Listen to the feedback you’re getting from others in the organization who may be able to be more neutral because they aren’t as invested in the success of the change (be especially attentive to those who aren’t on the change team or driving the change functionally).

Most important, manage your self-talk: notice whether your internal monologue is telling you that it’s a bad thing if some part of the change isn’t working and needs adjustment. Because if you’re telling yourself that need-for-adjustment = failure, then you’re also probably working hard to convince yourself that the change is working perfectly, so you feel successful! Revise your self-talk to acknowledge that recognizing and making needed adjustments is the only real way to succeed. In other words, work to make the mindset shift you now know is core to any change. Go from thinking that making adjustments is going to be difficult, costly, and weird to understanding how it can be easy (doable), rewarding, and normal. Once you’ve made that mindset shift, you can use all the skills and tools you’ve built in learning the change model to institutionalize the ongoing adjustments that will be needed.

Decide what needs changing. Remember Goal #1 of Step 1: “Surface and frame the change.” As you review the current reporting that’s showing you something isn’t working with the change, use the challenge question frame you learned in Chapter 6 (“How can we . . . ?”) to define exactly what’s not working. For instance, in the company that’s changing the production process for their core product, the change team noticed that the automation they incorporated into the process wasn’t yielding the time savings they’d targeted. They created a new challenge question to define the problem: “How can we better use our new automation to get the cycle time reductions we need?”

Once you know what the challenge is, look at the current state (your new, postchange current state) to see what might be getting in the way. When our manufacturing friends did this, they realized the problem was in the hand-off step from automated back to manual: there was a bottleneck because the pieces were going through the automated processing unit faster than the person on the line could then do the next, manual steps; the partially completed products were piling up as they came out of the machine. The change team realized that they needed to put two people on the line instead of one at the point where the product transitioned back to manual.

Build the adjustment into your existing plan. Rather than thinking of the adjustments you make as one-offs, look at them as an extension and refinement of your existing change and transition plan. (This is a big part of “institutionalizing.”) Look at the part of your WBS (Work Breakdown Structure) that focuses on the area that now needs adjustment, then create a new deliverable and tasks within the appropriate work stream. In the manufacturing example, there was a “production line” workstream and an automation deliverable (“Design and build automation into the production line as agreed”) and the tasks to complete it. The change team created a new deliverable in the production line workstream to address their new challenge: “Integrate all automated and manual production steps to achieve maximum efficiency.” They assigned a deliverable owner and agreed on the needed tasks. Looking at it in the context of the previous related deliverables and tasks helped make sure they could take full advantage of the work that had already been done and not reinvent the wheel (or in this case, the production line).

Support those most affected. Remember that when you make adjustments there will be a bit of related transition planning as well. Those most affected by the adjustments will almost always be the same people most affected by the original change plan in the area of the adjustment. In the case of the manufacturing company, the most affected groups for the production line deliverables were the people working on the line and the mechanics maintaining the line (who now also maintain the machines that do the automated parts of the work). The change team created a mini-transition plan to support those two groups through their change arc around this adjustment.

The plan focused on explaining what the adjustment was, why it was happening, and what it would look like when it was complete (employing the levers of “increasing understanding” and “clarifying priorities” to help these folks through the proposed change part of this new mini-change arc). They also needed to provide forums for those employees to ask questions, share concerns, and get the answers they needed (giving support). Finally, the change team agreed to let the line employees decide how they wanted to allocate the new responsibilities among the team (giving control). All of this was in the service of helping those most affected make the needed mindset shift to see the adjustment as easy, rewarding, and normal.

Individuals

You may be tired of hearing me say this, but I’ll say it anyway: including employees—especially those most affected—in the work of making ongoing adjustments to a change effort is almost always hugely helpful. Let them know that their feedback has allowed you to see a need for adjustment (if that’s true); involve them in coming up with the challenge question; and make them a part of deciding how to address the challenge. Doing this is perhaps the most powerful way to increase their understanding, clarify and reinforce priorities, and give control and support—and therefore accelerate these folks through their transition around this latest change. Getting input from the people who are closest to how the work is done helps make sure that your solution is a good one—and that it’s feasible, impactful, and timely.

It’s easy not to involve employees at this point in the process: you can convince yourself that since you already did such a good job involving them in the initial change, they’ll be fine with any adjustments. But this generally just isn’t so. In fact, if your employee population isn’t used to significant change, they may well be congratulating themselves on having “made it through” and hoping that they can just relax for a while . . . and being confronted with yet another change, even if it’s a relatively minor adjustment, can feel overwhelming to them. By recognizing that most people will need to move through a whole new change arc around adjustments that affect them, you can avoid a lot of unhappiness, resentment, and lost productivity.

Organization

One important way to institutionalize the change at this point is to make sure that the goals and ways of operating you’ve created with the change are built into the company’s ongoing systems and processes. For example, Moment hired their first head of marketing, Aliya, who was the Tom Sawyer for the deliverables around social media. Once those are done, the ongoing tasks and measures of success relative to that should become part of her job description and KPIs (key performance indicators), to “bake in” those new ways of operating.

Many of the adjustments needed at this point in a change effort are simply further improvements or alterations to a newly made change that was directionally correct but still has bugs to address—and the adjustment usually involves more work on a system, process, or structure. The earlier production line story is a perfect example of this: in creating a new process, the change team didn’t realize how the automated and manual parts of the process would interface, because they hadn’t experienced it before. In making any change, there will almost invariably be these kinds of unexpected consequences: it’s nearly impossible to anticipate everything that will result from making a major change. Many of these consequences will be relatively minor and can be addressed by tweaks to the existing plan (as in the example above). Sometimes, though, making a change will uncover organizationwide gaps or problems in systems, structures, or culture that have to be addressed in order to sustain the change long term—and that, if not addressed, will make the organization and its people less change-capable going forward. We’ll talk about this in the final goal of Step 5.

——————GOAL #3——————

Make Systems/Processes, Structures, and Culture More Change-Capable

Leaders

Step 5 is in some ways odd. The change team, if they’re doing their job right, will have a dual focus: both very granular and specific (monitoring and reporting progress, deciding on and making adjustments to keep the change moving forward) and also far-reaching and organizationwide (making systems, structures, and culture more change-capable overall). This is where the leadership attribute of being farsighted, with its associated skill of pulling back the camera that I talked about in Chapter 9, will come in very handy. As a change team, you’ll have to sometimes pull the camera pretty close to the action—for example, in meetings where you’re reviewing the data on your measures of success and focusing on the details of what’s not working as you’d hoped, and what you’re going to do about it.

You’ll also have to know when to pull the camera way back, as Steven did when talking with Jade at the beginning of this chapter, to recognize organizational impediments that may get in the way not only of your current change but of changes yet to come. How can you do that? Here are some questions to ask in Step 5 when you encounter a systemic, structural, or cultural problem that’s getting in the way of your change; asking these questions will support you in being farsighted, so you can step back and see how big the problem actually is.

Have we run into this before? Just asking this question immediately helps you pull back the camera; it encourages you to widen your focus from the particular situation where an organizational element is impeding this change, to think about other places the same element may also be getting in the way. If a system/process, structure, or cultural assumption has come up previously as a problem, odds are it’s having a broader, perhaps even organizationwide impact. For example, I recently worked with an online retailer that was trying to create better personalization on their site (“personalization” in the sense of being able to make good recommendations to customers, such as “If you like this, you might like that”). They realized that the lack of a sitewide consistent digital product catalog was not only impeding that effort but also making it hard to analyze sales of like products and to see where the company had gaps or overstocks in popular item types.

What else would be easier if we resolved this? This is another broaden-your-focus question, one that looks at the other side of the coin: the organizationwide potential for improvement if a system, structure, or cultural assumption is changed. The change team at the manufacturing company realized, in Step 5, that having a manual inventory management system was definitely limiting the effectiveness of their new production process for the core product. But when they asked this second question, they realized that improving this system would significantly increase their ability to respond more quickly to changing customer demands for all their products. They decided to move to a cloud-based inventory management system—one that would not only allow for much greater responsiveness in production changes—but which could easily be used to support new products and new production processes.

Why haven’t we already addressed this? This is a very interesting question which can, if honestly asked, shine a light on your organization’s historical difficulties with change. If a systemic, structural, or cultural element has shown up before as an impediment to change and hasn’t been addressed, it usually means that people in the organization have assumed it’s too big or too deeply embedded to be changed. Even if that has been true in the past, it could be that now that the organization has some skills and some momentum around change, the issue can finally be addressed.

Cultural impediments to change are the most common culprits in we’ve-seen-it-before-but-haven’t-done-anything-about-it situations. One client was trying to support greater innovation, and in the process of making change to support that (they focused on incorporating time and opportunity to innovate into people’s jobs, provided skill development, and incentivized innovation through spot bonuses), they ran into the fact that their culture had a historical bias against risk-taking. The change team (and the senior team) recognized that this had come up before as an impediment and that they had simply ignored it because the company’s leaders believed the issue wasn’t changeable (even though they didn’t want to say that out loud). Fortunately, it wasn’t true. The change team undertook a separate change effort around the culture. They started by clarifying the company’s current values and discovered that an implicit value was “caution.” They shifted that to “science-based”—close enough to resonate for their employees, yet a reframing that allowed them to define preferred behaviors for that value like “Find new solutions to critical problems” and “Question past assumptions.”

Once you’ve asked these questions, you’re much more likely to have a sense of whether you have “organization-sized” problems in your systems/processes, structures, or culture—problems that will not only get in the way of your current change being sustained but that will make it difficult for you to become fully change-capable as an organization.

Individuals and Organization

The good news (as I’ve been saying throughout this chapter) is that you have what you need to make these new organization-level changes: the five-step model with the change arc at its core. I hope that now you’re getting the sense of how you can thrive and prosper in this world of nonstop change. Once you have the understanding, mindset, skills, and tools to make one change, you have what you need to make any change. These are truly core, multiuse skills.

You may remember, in Chapter 4, I offered the idea of the organization, with its systems, structure, and culture, as the bridge that everyone in the organization has to traverse in order to reach any changed future state (Figure 20). And as with a real bridge, if the elements are too complicated, are disconnected, or aren’t sufficient, people won’t be able to rely on it to take them where they’re trying to go. I strongly recommend that you revisit Chapter 4, where I shared an overview of how systems, structures, and culture can be antichange. Now that you understand the change model and the change arc, I suspect (I hope) these insights will be even more useful as you think about how to transform systems, structure, or the culture of your organization to make it more change-capable—that is, to make your organization a bridge that will support everyone to make needed change, now and ongoing. As an added support and reference, if you go to changefromtheinside.com, you’ll find we’ve incorporated some of those insights from Chapter 4 into each step of the model to support you as you work to improve your organization to make it ever more change-capable.33

FIGURE 20. Leaders, individuals, and organization

One day you’ll wake up and realize that nonstop change really has become your new normal; that you’ve stopped expecting things to “stay the same”; that you feel capable and confident to keep evolving; that you even—gasp!—may be starting to enjoy figuring out how to surf the waves of change. You feel as though you know how to accelerate your own movement through your personal change arc around new changes as they arise; you don’t feel held hostage to your own impulse toward homeostasis. You realize you can help others accelerate through their individual change arc, too—and you embrace that as an important part of being a good twenty-first century leader.

You’re becoming change-capable.