12 ■ Knowledge Advantage and Why You Should Share Your Knowledge

Chapter Objectives

• Illustrate how I stumbled onto the café and how it impacted KM systems

• Case study on the café environment through mentoring

• Explore why you should share your knowledge

• Formulate an epilogue

12.1. KNOWLEDGE CAFÉ FOR COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

National Football League coach Pete Carroll has said, “Each person holds so much power within themselves that needs to be let out. Sometimes they just need a little nudge, a little direction, a little support, a little coaching, and the greatest things can happen” (Doyle, 2018).

Everyone needs a mentor. We all need a coach.

Let me tell you the story of how I stumbled onto a Knowledge Café and how it impacted our organization’s KM system.

I started developing CoPs. As the CoPs matured, they began to evangelize across the enterprise. Within a year, we identified 50+ CoPs, and KM activities began to grow across the organization. However, something was still missing. I needed to see some KM momentum. My curiosity increased. There were still silos, and CoPs were even duplicating activities. I thought that there had to be a way to bring all the active CoP practitioners together to know what everybody is doing. Sure enough, Knowledge Café was the appropriate vehicle for this kind of informal gathering for knowledge management enthusiasts in the organization. At the first café at TxDOT, we had about 80 percent of the divisions and districts participating. Attendees possessed different levels of maturity and sophistication. Several identified CoPs were present to discuss what was happening at different CoPs, the technology tools being used to share and collaborate, what was working and what was not working, challenges of knowledge capturing, mentoring, and knowledge sharing among CoPs.

The café was simple, with no preconceived outcome. Everyone was involved in the learning process. At the café, we learned that some of the CoPs were already advanced using some technology collaboration tools and maturing in mentoring members. One of the CoPs had previously conducted a knowledge audit for their CoP. They identified all the skills and expertise within their CoP, developing a knowledge map that traced all 150 members with specific skills and capabilities. They developed an expertise directory complete with frequently asked questions. It made my job easy. Other CoPs copied from them rather than reinventing the wheel.

One of the CoPs I support, Surveyors and Geomatics Scientists CoP, was way ahead of the curve. I provided them with guidance for a simple knowledge audit for their CoP, but they went over and above in conducting their CoP knowledge audit and mapping. A knowledge audit takes an inventory of an organization’s knowledge capabilities to understand where an organization stands in terms of knowledge management and its knowledge assets. An audit identifies precisely what knowledge the organization has, what knowledge they would require in the future to meet their objectives and goals, and maps the knowledge.

Needs Analysis is to identify precisely what knowledge the organization has and what knowledge they would require in the future in order to meet objectives, goals, and mapping (Kumar, 2013).

This CoP, through their knowledge audit, can identify all knowledge produced within the CoP, who produces the knowledge and uses it, the frequency of its usage, and where the knowledge resides or is stored. KM is all about knowledge stewardship—knowing what we should know and creating new knowledge.

Innovation happens at the intersection of knowledge-sharing and intelligent-exchange of ideas.

12.2. MENTORING CASE STUDY: SINCERE MENTORING IS ONE OF THE MOST EFFECTIVE WAYS OF KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER—SANDRA JACKSON

This case study is from Sandra Jackson, PMP. Sandra was a mentee. She has CTCM, SAFe 4, and Agilist certifications and was my successor as president of PMI Austin Chapter, with a membership of 3,500 project, program, and portfolio managers in Austin, Texas. Here is Sandra’s case study:

No organization I’ve worked for has a formal knowledge transfer program. Sadly, in terms of investment into KM, not nil to none. Regarding the challenges I encounter transferring or sharing knowledge, we are not being given enough time for knowledge sharing and transfer. For the most part, if done at all, knowledge transfer is done at the last minute when a person is leaving the organization. The time spent with the person leaving is limited and rushed due to their other commitments that they are trying to fill before they leave. Often, the knowledge has not been adequately documented, or there is no documentation at all. It’s all in the leaver’s head.

On knowledge transfer technology tools, it’s appropriately filing the information in a way that it can be accessed. For example, on SharePoint, I have to use keywords/phrases to locate/search for information. That can be a challenge when the information you are looking for is not correctly filed or indexed.

One of my most significant challenges in the project space is getting information from other people. You have to schedule meetings and set a date/time when they hopefully will be able to talk to you for the duration of time requested. At times, it’s easier to go online and get the information I’m looking for. But it doesn’t take the place of asking someone who knows the intricacies and idiosyncrasies of the information and knowledge you are seeking.

Share my knowledge? It brings less stress on you—especially if you are the only one who has the knowledge. It’s empowering to others. Also, when you share knowledge, it opens you up to receive knowledge. Knowledge transfer can be both a challenge or fun. Knowledge transfer can be a challenge if the other parties involved are not willing or limit what they share because they are intimidated, or it can be fun when both parties recognize the benefit of sharing and how it will add more skills to their toolbox.

On painful results from lack of knowledge transfer, I’ve encountered? I would say it left me feeling very disappointed with the person I was seeking knowledge from. I desperately needed their help before they left the company, and they chose to make themselves unavailable. I ended up gathering as much information as I could from the Internet—but not enough to feel confident in taking on the position’s responsibilities.

It was my joining the PMI Austin Chapter board of directors that I experienced knowledge transfer through hands-on mentoring. This was intentional. From day one, I experienced knowledge transfer on steroids, feeling the importance and joy of knowledge transfer. Café style knowledge transfer simplifies the whole knowledge system. Taking a leader by hand to observe one’s knowledge and leadership through sincere mentoring is one of the most practical knowledge-transfer methods.

When I handed over to Sandra as the PMI Austin Chapter board president, there was no need to provide her a formal handover note except that the boarding process required it. I literally took her by the hand to observe everything, we exchanged knowledge, and I made knowledge transfer part of our governing process. When I spoke to other speakers like Dr. John Maxwell, or contacted the police chief, mayor, or the governor, and participated in the PMI regional president calls, she was intentionally keyed into all of them as part of the KT process. I can boast that if I had stepped down halfway into my tenure, Sandra could’ve taken up the mantle and ran with it—thanks to the mentoring and knowledge-transfer culture we established.

One of my life’s missions is to mentor one million authentic servant-leaders. You don’t have to change the world; what you do is to mentor one person who changes another. One of my mentees, Chris DiBella, MBA, CSM, a passionate project manager, and Scrum Master, quipped that far too many companies have teams set up that act as individual entities within the company, which they should to a degree. Still, the issue is that some teams are stronger than others, perhaps due to a project manager handpicking whom they consider being the most qualified. There is no cross-transfer of skills or knowledge base to make the other teams better, and it almost seems like some people are unwilling to go to whom they consider a “weaker or lesser” team. This attitude only inhibits growth at the individual and team level and the cultural level of the organization.

I believe that everyone needs mentors and needs to mentor others, too. This is a dynamic knowledge-transfer tool. A mentoring environment is a KM culture.

12.3. WHY DO I SHARE MY KNOWLEDGE?

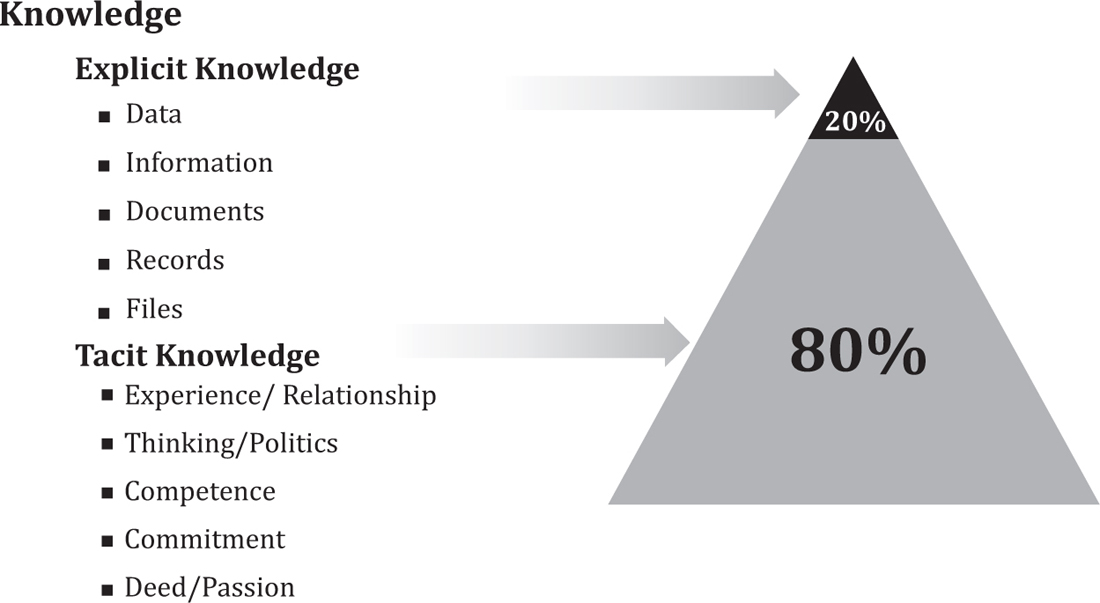

Every KM environment is a knowledge exchange and sharing environment. Most knowledge users are not aware of their knowledge or how valuable this knowledge is to other knowledge workers. Because tacit knowledge provides context for people, places, ideas, and experiences, it is considered more valuable.

Figure 7: Knowledge assets of an organization.

The knowledge assets triangle was adapted from Allee’s (2001) 12 Principles of Knowledge Management (see figure 7). Knowledge assets of an organization are made up of tacit and explicit knowledge, and some have added the category of implicit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is easy to articulate, write down, and share. Tacit knowledge is gained from personal experience that is more difficult to express. Implicit knowledge is the application of explicit knowledge.

Eric Verzuh, in his internationally bestselling book, The Fast Forward MBA in project Management, contends that it’s so important to get all assumptions and agreements written down and formally accepted. He argues that the “written statement of work is a much better tool for managing stakeholders than is memory” (Verzuh, 2011, p. 51). Carefully writing down the project rules, like agreement on the project’s goals among all parties involved, control over the project scope, and management and stakeholders’ support, is a project knowledge process that should never be overlooked (Verzuh, 2011; see pp. 117 & 127). Capturing and reusing knowledge or lessons learned during and at each phase gate or review point throughout the project’s life cycle is a knowledge management process.

An example of explicit knowledge would be that you write down the process or instruction for developing a software code. Contrast that with some tacit knowledge. You missed a deadline, and a customer is upset. No one could calm the customer down, so Brad was called in. He has the skill to talk to difficult customers. After talking to this customer for 15 minutes, the conversation turned into laughter as you could hear the customer on the side laughing. Brad, how did you do it? Can you write it down? Brad said, “No, I can’t. I just talked to him.” This tacit knowledge is hard to write down. Interaction and observation are the best way to share and transfer this kind of knowledge.

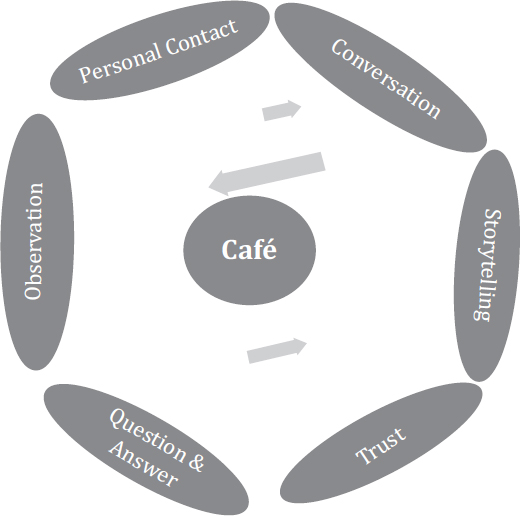

REQUIREMENTS FOR A SIGNIFICANT TRANSFER OF TACIT KNOWLEDGE

• Extensive personal contact

• Interaction and circulation

• Tight environment

• Trust

• Question and answers

Knowing what you don’t know is very important. Knowing what you don’t know that you are ignorant of is more important. I propose that conversation, personal contact, trust, observation, questions, and answers effectively extract tacit knowledge and close knowledge gaps, as seen in figure 8. Knowledge is contextual. Tacit knowledge is also situational. You may never know that you possess innovative or solution knowledge unless a problem arises or you are asked about it. Everyone has a story to tell. In that story is your tacit knowledge. Learning doesn’t always happen in the classroom. When you say it at the café so everyone can learn, your knowledge becomes richer. Stories at the café stir up tacit knowledge that you identify and document in your knowledge register. various cultures and people have different ways of acquiring and communicating knowledge. Where is the knowledge we need to do our work? Knowledge resides in people, systems, culture, or the environment. How do we get this knowledge and apply it?

Figure 8: Café and tacit knowledge transfer.

How do you create a collaborative team with a high level of trust without creating the space for it? You could be formal about it, but the café is a simple and informal and partially structured way of achieving the same objective—to get knowledge out of silos. It’s just one effective tool to create an environment of KM.

Create a space in the café to think alone and together, in person or virtually. In our high-paced work environment, we need a safe space to come together, to think, maybe to cry it out! Environmental psychology tells us that our mental space stands in direct proportion to our perception of physical space. Great ideas are not hidden in cubicles.

Albert Einstein was right when he said, “We cannot solve our problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” We need a knowledge learning culture to succeed in today’s world.

Why Do We Share and Exchange Our Knowledge?

We are not cisterns made for hoarding; we are channels made for sharing.

—Billy Graham

We share because the hand that gives is always on top! Every knowledge worker is a channel of knowledge, exchange, and sharing. The café mindset makes this possible as it stirs the culture. American activist Robin Morgan was right when he said that “Knowledge is power. Information is power. The secreting or hoarding of knowledge or information may be an act of tyranny camouflaged as humility.”

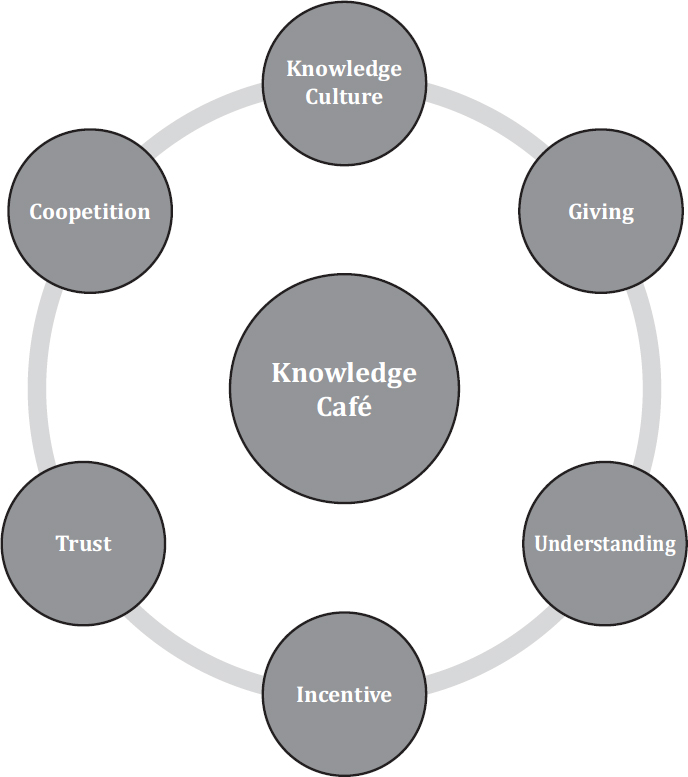

Why do some knowledge users hoard their knowledge while others share theirs (see figure 9)? At a global conference on KM in Los Angeles a few years ago, someone asked me, “Why should I share my knowledge with someone who is competing with me for a promotion?” To answer these questions, I’ll pose another question: Why do I share my knowledge?

I propose seven possible reasons why employees are reluctant to share their knowledge, and some rightly so.

Current economic conditions have placed a premium on an organization’s ability to be flexible, quick-to-market, scalable, and responsive to unique customer demands.

—Hiatt & Creasey (2003)

1. No knowledge cultures

Hiatt and Creasey (2003) emphasize flexibility, quickness to market, scalability, and responsiveness to unique customer demands. This kind of agility can be achieved in a café environment more effectively than in other settings. For there to be knowledge culture, there must be an environment of innovation and collaboration, with a strategy for knowledge sharing—as a Knowledge Café. Knowledge sharing is a Herculean task in an environment where there’s little to zero knowledge-sharing culture. As I said earlier, KM doesn’t just happen. The culture of knowledge sharing creates a knowledge workforce. Human beings do not readily embrace change. In the same vein, human beings and organizations don’t just embrace knowledge management. Like an organizational mission, KM is deliberately and meticulously managed and enshrined into the culture of an organization.

Figure 9: Why some share and others don’t.

Demand for knowledge creates a knowledge-sharing habit. Participants of a café and KM are willing colleagues who are curious to learn from others to create a learning process and knowledge culture.

Some employees see KM activities, such as a café, lessons learned, or communities of practice, as additional tasks that compound their daily workload. Many organizations are siloed in such a manner that makes it unnecessarily burdensome for knowledge workers to share their knowledge without feeling guilty about abandoning their regular project duties. A café mindset is making knowledge sharing part of our daily routine and our culture. Knowledge sharing should be painless if it’s part of the organizational culture. In my house, we clean as we go. So, after dinner, no one drops their dirty dishes into the kitchen sink. It’s natural for everyone to clean up after each meal. Knowledge sharing shouldn’t be an additional burden but part of the culture and routine.

Incorporation of the café practices in the organization’s business is part of organizational agility. Change has become the norm for all organizations. It has become a culture, so organizations develop a change competency and change agility, which is enshrined in their way of doing business. It becomes a way of life—a voluntary régime. Knowledge sharing creates a culture of knowledge. We explored knowledge culture in chapter 6.

2. People compete rather than complement: encourage “coopetition” and succession

We have been in prison from wrong teaching. By perceiving that cooperation is the answer, not a competition, Alfie Kohn (an American author) opens a new world of the living. I am deeply indebted to him.

—W. Edwards Deming

Employees get 50–75 percent of their relevant information directly from other people. Individuals hold the key to the knowledge economy, and most of it is lost when they leave the enterprise.

Most of us rely on information and knowledge from colleagues and teammates to do our work. There is a balance between cooperation to work together and compete in the workplace to do your best; this is coopetition. Amazon and Apple became “frenemies” when each realized, “If you can’t beat them, join them.” Both competitors joined forces to create the Kindle iPad app. This type of coopetition is beneficial for all major enterprise applications. Coopetition is exemplified in project Connected Home over IP. Apple, Google, and Amazon, who are competitors cooperating to make our home gadgets talk to each other, which is called project Connected Home over IP. This project will work to create a new standard that will make it easier for the fragmented ecosystem of smart home products to work together—and cafés. That is the meaning the joint distribution of the coronavirus vaccine between competitors Merck and Johnson and Johnson represents. I think that this is smart.

Coopetition is cooperating with your competitors, building synergy so that everyone wins. David McMillan, of the HR Division for the Texas Department of Transportation, defending succession planning as a KM tool, said, “People don’t like to succeed; they compete.” This saying is true—but sad! David is right because the test of success is succession. Succession planning is a technique of knowledge management for preparing. You don’t raise a successor if you are competing with them. In a public company governance survey by the National Association of Corporate Directors (2017), 58 percent of directors indicate that improving CEO-succession planning is a critical improvement priority for 2018, up from last year when 47 percent of respondents reported this as a crucial priority.

The good news is that in 2019, public company boards are more focused on long-term succession planning now than in years past. The same year, 80 percent of public company respondents to the survey reported discussing long-term (three to five years) CEO succession plans in the previous 12 months (Edgerton, 2019). This is succession rather than competition. When there’s a culture of succession rather than competition, knowledge sharing thrives.

SUCCESSION PLANNING DONE RIGHT

Here are some examples of succession planning done right.

• By establishing a great professional development pathway, IBM creates a thriving and positive company culture that allows candidates to compete at the same level. Consider when IBM’s senior vice president Virginia Rometty took over as its first female CEO from Samuel J. Palmisano. The company created the environment.

• Before he stepped down as CEO of Apple, Steve Jobs prepared his succession plan at Apple University. Their digital curriculum is an excellent example of how technology can be used to prepare an organization’s leadership succession.

• In February 2017, the luxury retailer named the company’s COO, Daniella Vitale the new CEO. Her predecessor and mentor, Mark Lee announced, “It’s time to turn the day-to-day management over to Daniella, who has long been my planned successor and is uniquely qualified to take the leadership reins.” (Ang, 2018)

In 2018, I was elected president of the project Management Institute (PMI) Austin Chapter. PMI Austin is one of the largest PMI chapters in the world, with membership of more than 3,500 professional project, program, and portfolio managers. I realized that coopetition is the way—a necessary element of resilience and succession. Coopetition means knowledge exchange. It creates a win–win situation. We increased the chapter’s membership by over 400 in 2018. We increased and strengthened membership, doubled the value offering to members, increased retention, generated lots of excitement among practitioners, and received 97 percent overall customer satisfaction. But in my opinion, these achievements alone do not describe our greatest success. The 2018’s board leadership success is ultimately dependent on the success of the 2019 board. We are not competing with our successors!

Authentic leaders celebrate the success of their successors. A business strategy and culture that ignores coopetition and throws succession planning away will have knowledge-transfer challenges.

These leaders are happy when their successors are greater achievers or excel where they didn’t—because your successor’s success guarantees the sustainability of your success. Hoarding doesn’t complement succession.

Competition in itself is not a bad thing. It all depends on the intention. I compete with the goals I set for myself. Unconsciously, we compete for everything. Steinhage, Cable, and Wardley (2017) identified that “some research studies suggest such competition can motivate employees, make them put in more effort, and achieve results. Indeed, competition increases physiological and psychological activation, which prepares the body and mind for increased effort and enables higher performance.”

Keeping your knowledge from others may sound like a smart strategy, but it depicts a need for knowledge growth, awareness, incentive, and competitive knowledge sharing in an organization. In many organizations, especially in the public sector, in some departments or offices, one person houses mission-critical knowledge that the organization needs to conduct its businesses. I have seen situations where only one person is the subject matter expert in a particular business process like risk management, business strategy, tool deployment, specific business analysis methodology, specific metric analysis, report generation, and project or program management. This individual or project team member may be the project manager and the go-to person with unique competencies for the project or program. There will not be a knowledge culture in this kind of environment.

Why is it that if an expert or a knowledge manager goes on vacation, progress is put on hold? For instance, there are some offices where only one person develops a specific critical report on the organization’s projects’ critical path. This expert may have been doing this particular report for as long as many team members recall. This means the entire team has to wait for that person to return before moving forward. These experts use their specific experience and skill as leverage or a bargaining chip for individual competitive advantage. Knowledge employees will continue to hold the entire office or division to ransom because of their knowledge, expertise, and special skills until everyone convenes at the café. This mentality proves that there is a cry for a knowledge culture.

An environment where information and knowledge are siloed is dysfunctional for knowledge workers. I call the environment where employees hoard their knowledge rather than sharing it a tight-fisted knowledge environment. Everyone guards their knowledge and their jobs. Everyone knows that an unshared knowledge mindset is an unspoken culture enshrined in the organization’s eternal psyche and culture. It makes employees compete rather than complement each other. Author Stan Kroenke (n.d.) was right when he said that “Economics is about creating win-win situations. But in sports, someone loses.” Knowledge management is within the context of economics and not sport. We can compete and complement at the same time. I don’t intend to diminish the psychological phenomenon of rivalry in the workplace. I do not believe that I’ll lose something when I share my knowledge. I’ve always won!

Within the purview of KM, the right competition should be deemed the one where the most knowledge is shared and where knowledge transfer matches the speed of disruptive technologies and job mobility. The café creates an environment where employees are inspired to share their knowledge. They will compete on who shares the most and not who hoards the most knowledge. Know that whenever there is a competition that impedes knowledge sharing, someone loses. We should compete so that everyone wins! Covey (2004) summed it up when he said, “When one side benefits more than the other, that’s a win–lose situation. To the winner, it might look like success for a while, but in the long run, it breeds resentment and distrust.”

3. Knowledge sharing is not rewarded

I acknowledge that many people have shared their knowledge with colleagues who eventually took over their jobs or edged them out in a job competition. Rather than serving as a lesson against knowledge sharing, the takeaway should be to practice political savviness. Those who feed on the “cheap advantage” don’t get too far, as I discovered in the research for my next book on political savviness and project management.

People who share the most knowledge within our hyper-competitive workplace inspire me to expound upon the significance and efficacy of incentives, rewards, and recognition as a knowledge-sharing strategy for executing an enterprise KM.

Encourage employees to share knowledge by incentivizing the sharing. In some instances, project team members feel that they are being punished for sharing their knowledge, which they believe is their personal asset. During the developmental stages of our KM program at Texas DOT, I organized an enterprise knowledge fair and café that had 80 percent participation from all divisions and districts. As I was engaged with District Engineer John Speed in Odessa, Texas, he said, “I believe in the principles and methodologies of KM, and we practice it. I even make knowledge sharing a requirement for a promotion. If you want to get promoted, you start sharing your knowledge.”

This is amazing! Employees should not be made to feel like they will be punished for sharing their knowledge. An atmosphere of reward and recognition should be created for the KM environment.

Some organizations such as Accenture perfected this act in what they called “gamification,” which is an approach to a rewarding collaboration. It encourages and incentivizes its employees to display everyday work-related knowledge-sharing behaviors encapsulated in what is called the 3Cs:

• Connect to people and content

• Contribute their ideas, insights, experience, and knowledge

• Champion by encouraging their colleagues to go the extra mile

These behaviors are reinforced through employee performance-management processes, with performance factors linked directly to collaborating effectively. The company calculates a quarterly “collaboration quotient” for each employee as a means of motivating employees to engage more actively in effective collaboration and sharing. The score is based on over 50 activities tied to its 3Cs. Scores are weighted toward quality rather than quantity. For example, an employee who writes blog posts is rewarded more based on the number of views and downloads the blog receives, not merely the number of posts he or she has written. Scores are reviewed quarterly, and the program recognizes top collaborators. Leadership gives these employees a recognition letter, a small monetary award, and virtual badges to display on their internal People profiles; these awards are noted in their annual performance reviews (NCHRP, 2014).

While some people share their knowledge naturally, gamification incentives encourage sharing and collaboration that yields incredible results. Free coffee works, too.

4. Fear of sharing knowledge

Fear is the opposite of faith. Ignorance leads to fear. I encourage you to believe it! It is impossible to fear and believe in yourself or a higher being at the same time. People fear because of uncertainty, insecurity, the unknown, the future, and by nature. We all fear something. People ask me why I am excited about sharing my knowledge. My answer is because I’m a believer! I’m also a “possibilitarian!” American graffiti artist, speed-painter, and author, Erik Wahl (2019) said that “every child is an artist,” but when we grow up, we are told that we can’t. We can’t disrupt the convention. Everyone has knowledge if you have ever said or done something and can share. How often do we deploy an enterprise application or buy a business tool and only use a few of its capabilities because of ignorance and fear? I believe everything is possible.

Not taking leaps of faith has consequences. For example, when Blockbuster faced or didn’t face their fears of the early rise of Netflix, it cost them their business. Another example is the challenge Apple faces by retaining a proprietary closed operating system. When we work in an environment of fear, it is impossible to cross-fertilize and share knowledge.

Café is the opposite of fear! To remove fears and open the doors of knowledge sharing, it has to be okay to share one’s knowledge—as well as your mistakes. Build organizational trust. The atmosphere of the café eliminates fears and builds confidence and trust.

5. Ignorance of the benefits of knowledge sharing

The hand that gives is always on top. People need the right information and knowledge to create the right attitude. We must acknowledge that the giver is not inferior to the receiver. A Knowledge Café brings enlightenment, creates space, and offers knowledge workers reasons to share what they know. As President Ronald Reagan said, “There is no limit to the amount of good you can do if you don’t care who gets the credit.” Small-minded people care a lot about who gets the credit.

6. Lack of understanding

Understanding is a fertile ground for knowledge, but understanding and knowledge are not the same things. You can have knowledge of something without proper understanding. You need to understand the knowledge that you possess and what should be shared.

According to the study of anatomy and physiology, “The cerebellum lies at the back of your brain and takes care of things like coordination, balance, and many more implicit functions that you don’t even think about. We would consider our cerebellum as our ‘intuitive brain’ ” (Wolf et al., 2009). The cerebrum lies in front of your brain and takes care of the movements you are consciously aware of. It is the part of your brain that can express ideas and direct your actions. It is your “intellectual brain” (Arnould-Taylor, 1998).

Your intellectual brain may know something, but your intuitive brain or your primitive brain may be on a different wavelength—not on the same page. Seek to understand the knowledge you have and the benefits of sharing what you know.

7. People shy away from sharing their failures

Some people ask if they should share knowledge of their failures. My answer is, yes, if the environment does not punish you for sharing your knowledge. Understanding vis-à-vis knowledge sharing means employing empathy; understanding something is to have a tested generalized insight, to comprehend, take in, or embrace. Understanding the place of knowledge sharing is key to answering this question. If you are insecure about your knowledge, you can’t make much progress within the circumference of knowledge exchange. Understand the purpose of knowledge exchange at the café. Understand political savviness. Besides doing the actual job, sharing what you know is the only way to showcase what you know and how much you know. You should understand why, when, and how you should share your knowledge. Have fun sharing it.

So, does the knowledge of my job offer me job security? My counter-question will be, “Would you prefer to die with your knowledge—so no one remembers you for such knowledge, no one uses that knowledge, and no one knows what benefits that would offer to humanity?”

The experience from the projects, programs, and portfolios that I am managing right now and the knowledge that I possess in my current job will only suffice for this current job. There are two significant types of knowledge: tacit (noncodifiable) and explicit (codifiable) knowledge. Others have contended for four types of knowledge, including (1) classified knowledge (e.g., historical knowledge); (2) explicit knowledge (e.g., organizational knowledge); (3) implicit knowledge (e.g., knowledge discovery in databases); and (4) tacit knowledge associated with unexplainable knowledge.

Implicit knowledge or inarticulate knowledge is knowledge in the application of explicit knowledge—those skills and competencies that are transferable from one job to another and from one person to another. The knowledge that I will need for my next opportunity is not necessarily the knowledge I have for this current position. Politically speaking, you are not sharing the knowledge of the next position. You are sharing the knowledge of your current job.

I have practiced two principles in my career. First, whenever I have a new job, I tell my boss, “If your standards for me fluctuate around average, I will quit.” Second, I affirm, “If someone needs to know anything about my current job, I will buy them lunch and explain everything I know. I will hold nothing back because I am working for the next position or promotion!”

There is a story of a couple who hated each other so much that they sold their house for $50 rather than the full market value after divorce. Neither of them wanted the other to profit from the house sale. This is what happens when we are not adept at sharing—everyone loses. We are better than that. Sharing is good. It’s refreshing to give, teach, and share what you know. It shows that you have an asset. It’s a way to build a legacy.