3  Organizing around Value Streams

Organizing around Value Streams

Nine departmental silos. In our experience, that’s the average number of silos that need to be traversed to deliver value to customers in any large organization today. Midsize and even small organizations are not exempt—most operate with silo thinking as their default. Is this your experience as well? If so, we can agree that this is a major, and likely an existential, problem.

The siloed organizational structure may appear efficient to those inside the organization, but it is generally a disaster from a customer’s standpoint. Almost anything that a customer needs is likely to require the coordination of many of these siloed functions, each of which often has its own interests and budgets. Consequently, it is either very difficult or sometimes impossible to achieve fast flow of value to the customer. Even just measuring end-to-end flow as a first step toward identifying the bottlenecks impeding flow is very challenging. Things get worse when an organization has a command-and-control, top-down hierarchy. The need to get things done by a throw-it-over-the-wall transfer from silo to silo is compounded by the need to traverse up-and-down organizational totem poles several times to get decisions. Essentially, slow lead time between silos and slow decision velocity across hierarchical layers create rigid organizations. Such organizations have struggled to develop the flexibility needed to survive in a fast-moving modern world and most will likely cease to exist in the pandemic era.

So what can be done quickly? One of the first steps toward breaking down organizational silos like these is to have business and information technology (IT) partners regularly connect with each other. For instance, a banking client of ours needed to set up an omnichannel organization for better end-to-end customer service and innovation. Their first step was to set up a consolidated unit that brought together business partners with agile teams that had hitherto been siloed in the IT organization. After initial and understandable agitation, this unit gelled into a larger, unified team of teams. Another client of ours had taken a similar approach, augmenting a business unit that was very conversant with Lean Six Sigma techniques with agile teams. Quite often a restructuring of the organizational structure is required to get things moving powerfully in the right direction. Of course, any organizational restructuring needs to be thoughtfully designed to be in line with agile principles and executed carefully under executive direction and oversight.

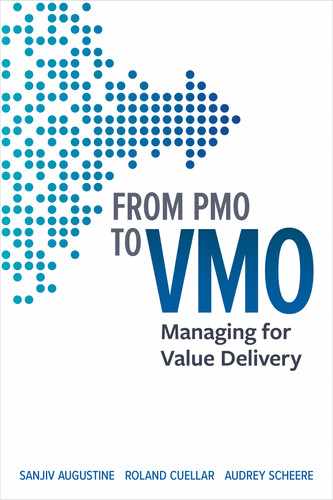

Longer term, what are the types of organizational structures that best support, enable, and grow agile methods? Things get very hairy when the agile notion of small, cross-functional, self-disciplined teams is introduced into our legacy organizations, as illustrated in figure 3.1. Rooted in the manufacturing efficiency mindset from the 1900s, the vast majority of firms worldwide are organized around functional specialties like marketing, finance, sales, and IT. Functional silos that mirror industrial-age production lines are also perpetuated within departments. For instance, within IT, a plethora of subspecialties form the typical basis of organization: requirements analysis, front-end software development, database development, database administration, network engineering, information security, and so on.

Figure 3.1: Agile teams in a legacy organizational structure

Even if we can stand up teams that meet Scrum’s guidelines for a cross-functional team of three to nine people with a scrum master and a product owner, we run into misalignment issues, some of which are captured in table 3.1.

If our older industrial-age organizational models are clearly mismatched for agile teams and methods, what are the more suitable alternatives in our current era?

Organize as Adaptive Networks of Teams

In recent years, a modern-day alternative to the industrial-age manufacturing-based organizational model has emerged and is gaining widespread popularity: the understanding of organizations as adaptive networks of teams organized around specific goals. Agile methods have long posited that small, cross-functional teams are the natural way for humans to work and to achieve high levels of team productivity and performance. Connecting these high-performance teams into adaptive networks of teams allows individuals and teams to share information and learning transparently across the enterprise and thus adapt quickly and dynamically to change.

Table 3.1. Organizational Misalignment with Agile Methods

• While agile methods call for small, cross-functional teams (3–9 people for Scrum), average team size devolves over time to 25+ people. |

• While agile methods call for integrated teams with all necessary disciplines represented on the core team, testers get pulled out of the formerly fully integrated team core, and end up in a separate quality assurance silo. |

• While agile methods call for team allocation of 80 percent or more for the core team to a single effort, team members end up multitasking on two to three projects at a time. |

• While agile methods call for locking down scope within a Sprint/iteration, untrained product owners introduce new user stories while Sprints/iterations are underway. |

• While agile methods call for accepting responsibility and team members handling work assignments among themselves, newly hired project managers end up assigning work to team members in Sprint/iteration planning meetings. |

• While agile methods call for daily stand-up meetings to be run by the team, they eventually devolve into status meetings for the project managers. |

As shown in figure 3.2, networks of teams can be formed and reformed dynamically into different constellations to meet the business goals at hand. This flexible networked model assumes change is normal and is qualitatively different from the traditional linear, mechanistic organizational model that assumes stability is the norm.

From the ground up, there is a clear recognition that each team or organizational component in the network has an impact on every other part as impacts ripple through the larger network. These teams of teams are thus set up so that people work together end to end across the entire organization to optimize the whole in response to changing business conditions. Optimizing the whole value stream from the customer’s standpoint is a core tenet of lean thinking and one that our VMOs should apply in figuring out how to evolve organization models away from the hierarchical and siloed model.

Figure 3.2: From the industrial to a networked organizational model

How should we handle scaling up from one team to networks of agile teams? How can we ensure that those networks of teams can be aligned with our business and configured and reconfigured dynamically? One of the most durable examples comes from W. L. Gore and Associates, best known for its GORE-TEX fabric developed originally for rainwear, see sidebar.

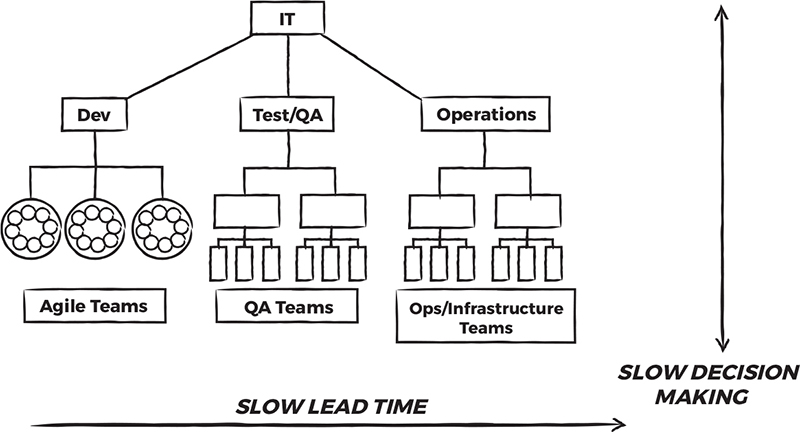

Within our organizations, one way we can deploy this network-of-teams model is by using the agile release train technique from SAFe. Multiple teams can be aggregated into an agile release train constellation, as shown in figure 3.3.

In the SAFe, agile release trains range from 50 to 125 people, with the upper limit based on Dunbar’s number. The anthropologist Robert Dunbar proposed that 150 is the cognitive limit to the number of people with whom we can maintain stable social relationships.1 Other anthropologists have put that cognitive limit closer to 300 people. As we look for ways to group teams into larger teams of teams, and those teams of teams into larger constellations, it is useful to consider how best to use this knowledge about cognitive limits to set group size limits at each level. Using guidelines as input into a scaling approach, we can set up the following:

• agile teams that range in size from 3 to 10 people

• multiple teams configured into agile release trains of 50–150 people

• multiple agile release trains configured into constellations with no more than 500 people

Figure 3.3: Scaling to multiple teams

Define Flexible Value Streams by Customer Journeys

Practically, how should one go about implementing the desirable adaptive network-of-teams concept in a modern business or other organization? Successful agile organizations tend to organize their team constellations around the customer in order to provide fast and frictionless cross-functional support and delivery of products or services. A value stream is the set of steps that are needed to provide continuous value to our customers. Organizing around the customer using a value stream approach implies the following:

• understanding the primary experiences, journeys, or touch points that customers have with the organization

• creating internal companies within a company that are organized into value streams that directly support these customer experiences

• creating flexible roles and responsibilities that allow these experience-aligned value streams to operate in a more entrepreneurial fashion

• allocating budgets in ways that support the customer value stream from end to end and that are aligned with strategic outcomes

Since we want and expect our VMO to be tasked with team formation and resource allocation, we need new ways of thinking about how to implement these concepts for more effective value delivery and true business agility. Fundamentally, we recommend a two-step approach.

First, evolve from project to product with experience-aligned teams. Second, assign work to teams, not individuals, to ensure alignment within teams.

These steps are covered in detail next.

Evolve from Project to Product with Experience-Aligned Teams

The idea of shifting the underlying organizational structure and processes of an organization from supporting projects to supporting products has been percolating for a while. The core idea is to ensure that the way we fund our work and the ways we organize our teams and organizations enable rapid response to user feedback and changing market conditions.

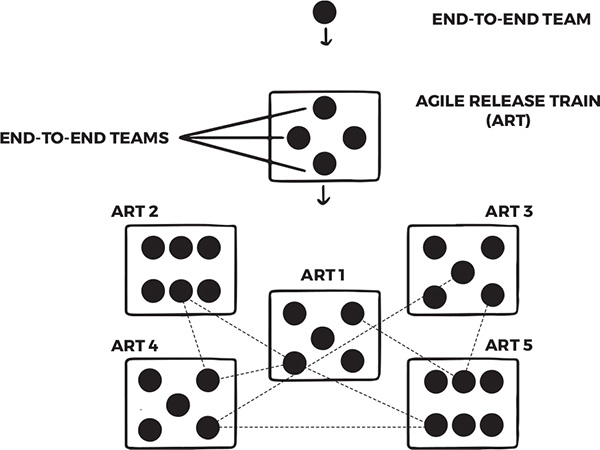

With a product model, rather than locking ourselves into a brittle organizational structure, our organizational design goal is to set up stable, cross-functional teams that are aligned around a customer experience in a flexible constellation. Rather than allocating team members across multiple projects simultaneously, our cross-functional teams focus on a single minimally marketable product (MMP) at a time. An MMP is a deployable set of minimum product features that address our customers’ immediate needs, that deliver value back to our business, and that allow us to test and learn. MMPs allow us to test our assumptions about our markets and customers and learn directly from the results we get from those tests. Figure 3.4 illustrates a basic model for creating an end-to-end team that is experience aligned.

In our example model, each experience-aligned end-to-end team is aligned with and focused on customer experiences like seamless delivery, flexible viewing channels, and effortless point of sale. Replacing the siloed organizational structure, each experience-aligned end-to-end team is set up with all or most of the functions necessary to deliver value from end to end within the organization to end users. Each team has several types of roles:

Figure 3.4: Experience-aligned, end-to-end team model

• product management, with product owners led by a product manager

• user experience experts, assisting product management with customer discovery activities

• team members conducting innovation experiments through direct end-user contact and prototyping

• other cross-functional members working on MMPs and systematically and progressively breaking them down into epics, features, and user stories in an overlapping discovery-refinement-delivery process

• team members with expertise in production or run activities

• team members focused on digital measurement support

This design helps implement what is known as an inverse Conway maneuver, and in addition to enabling end-to-end communication, it helps us eventually overcome issues with monolithic systems. Recall from chapter 1 Conway’s law, which famously states, “Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”2

Since we are solving for business agility, this inverse Conway approach evolves our team and organizational structure to promote our desired architecture. That is, we build our teams for flow and that in turn promotes a modern, decoupled architecture. There are several distinct advantages to decoupling teams from one another with this approach. It significantly reduces the cognitive load on each team, as well as the dependencies between teams. Finally, by building our team in a customer experience-aligned constellation, it ensures that our systems and flow of value will also be customer-experience aligned and flexible.

Assign Work to Teams, Not Individuals, to Ensure Alignment within Teams

There are manifold benefits to giving talented team members more autonomy. From a humanistic perspective, people really appreciate having control over how their jobs are done. The more autonomy, the greater their job satisfaction, their sense of well-being, and their overall work engagement.3 From a financial perspective, better work engagement drives higher productivity, lower costs, and greater value to customers. There is, however, a dark side to superficially increasing individual autonomy without understanding what changes need to be made systemically. In less mature agile organizations, efforts to increase autonomy among team members have counterproductive effects because they are not aligned with each other and not accountable to a larger organizational goal. In mature agile organizations, there is an understanding that autonomy, alignment, and accountability have to go hand in hand. As Kent Beck, the creator of extreme programming, has declared, “Autonomy without accountability is just vacation.”4

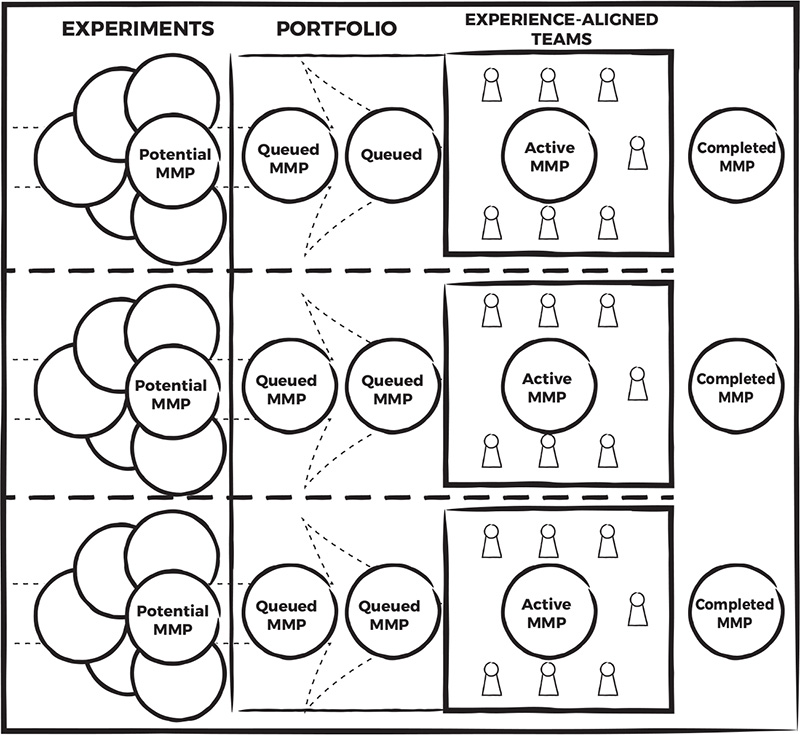

How do we create autonomy for our team members and also ensure they stay aligned and accountable for delivering on organizational goals and customer value? The answer is to first ensure we have experience-aligned end-to-end teams and then to assign work to our experience-aligned teams, and not individuals, as illustrated in figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5: Assigning work to experience-aligned teams

In this model, prioritized work flows from customer-facing experiments to a portfolio where work is queued for an experience-aligned team. Customer-facing experiments facilitate value discovery and allow us to go from business idea to initial identification of epics in a structured and disciplined way. The unit of work shifts from projects to MMPs. Projects are broken down into the smaller MMPs, and the MMPs are prioritized by product managers or product owners. By contrast, in organizations that have transitioned to the product approach, all product and nonproject work is initiated at the MMP level. Teams pull the work as they complete the previous MMP and become available. Further upstream, customer discovery experiments are run to validate or invalidate actual customer wants and needs. With a self-imposed work-in-progress limit of one MMP, each team works on just one active MMP at a time. When a team is done with the current MMP, they pull the next MMP in their queue, work on it, and deliver it. The cycle repeats for each team one MMP at a time and ensures a disciplined implementation of the lean concepts of pull and flow. We will explore this model in further detail in chapters 5 and 6.

Establish the VMO as a Team of Teams

In chapter 1, we introduced the VMO as a small, cross-functional, cross-hierarchy team that consists of key representatives who work collaboratively across the organization to drive change and ensure value flow to customers. The VMO has its own dedicated director, program manager, executive champion, and other elected representatives who work full-time to support them. In addition, the VMO has select linking-pin representatives.

The VMO’s linking-pin representatives ensure organizational overlapping between the VMO and agile teams and also between the VMO and an executive action team. By belonging to both their respective group (either an agile team or the executive action team) and representing that group on the VMO, they help with alignment across the organization. For example, a chief information, operating, or executive officer will represent both an executive action team and the VMO. Similarly, a scrum master will represent her team and the VMO, and a release train engineer represents the agile release train and the VMO. These interconnections among the various levels and areas of the organization need to be made carefully, with the goals of enabling the flow of value and facilitating organizational change. A well-known application of this linking-pin model is General Stanley McChrystal’s team of teams.5 See the sidebar for more.

As simple as they may appear, we know that putting these principles into practice is extremely hard. That is because implementing this network model requires both structural and operational change—that is, we need changes to our organizational structure and changes in the ways we operate. That said, once we realize that the alternative may be to go out of business over the long term, or even perhaps the short term, we can develop the fortitude necessary to enable these changes.

Fund Experience-Aligned Teams by Value Stream

Rather than making funding decisions at the beginning of a project and locking them in for the duration in industrial-age style, we want to ensure that our teams are funded in a way that drives business agility. If we borrow from the venture capital model, this means that our organizations will need to establish a funding model where we can take calculated risks and invest in strong entrepreneurial teams. The venture capital model also explicitly acknowledges the inherent risk in all our investments. The venture capital world is governed by the power law, which holds that only a small number of investments will generate the majority of financial returns, and the rest will generate little or no returns. This calls for a very different mindset and approach to funding our experience-aligned teams.

In most companies, the budgeting and funding process is driven by plans and a waterfall structure. That is, yearly budgets involve an inordinate amount of up-front planning, estimation, and accounting work. Once budgets are created, funding outlays are typically locked into the annual budget. The target annual budget is thus inextricably tied to long projects and initiatives, locking teams into predetermined efforts that may or may not deliver successful business outcomes. Overshooting the budget is frowned on, driving very conservative funding toward the beginning of the year. Paradoxically, underspending is also frowned on, causing some incredibly wasteful behavior where departments find ways spend their money toward the end of the year to avoid having their budgets cut the following year. This rigid yearly budgeting and funding process generates tremendous amounts of waste, and it is also perhaps the greatest obstacle to business agility.

To fully leverage the investment in our agile teams, and to manifest true business agility, we will need to transition our funding to an entrepreneurial and incremental model. Our VMO will need to do the following:

• work with finance teams to ensure they understand we will need changes to the existing annual budgeting and funding model and to enlist their help in making those changes

• use yearly budgets to fund experience-aligned teams for longer periods of time

• break the waterfall habit of locking funding outlays into the yearly budgets. Instead, make adjustments at least quarterly to funding outlays based on business outcomes

• make regular adjustments to product functionality, aggressively funding the MMPs that outperform and aggressively terminating the ones that underperform

We will explore these new funding techniques in detail in chapter 7.

Summary

Because many organizations are still structured in a way that impedes agile methods, one of the most important steps toward agility is to form experience-aligned teams. Two key responsibilities of the VMO are structuring dynamic networks of experience-aligned teams and creating a customer-centric model for funding and assigning work to them.

This enabling structure of a network of teams organized around specific customer outcomes helps value to flow unimpeded across the entire organization. To organize around the customer with this value stream approach, the organization must first understand the customer experience as customers consume products and services. Then they can create entrepreneurial company-within-a-company units with flexible budgets and roles that will dynamically support the customer experiences.

After the experience-aligned teams are established, work and funding should be allocated to the teams following the dynamic needs of a product model rather than a project model. The VMO will act as a team of teams, which ensures that all teams remain aligned to company goals and outcomes. Quite often such alignment will require establishing an enterprise-level VMO or other connection with a high-level strategy group in the organization.