INTRODUCTION

Uprising

Using your workforce as an engine for innovation is critical for our economy. Who knows better about what makes a quality operation than folks who are in the front lines?

—Thomas Perez, former U.S. Secretary of Labor

Although the massive civil outburst following the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. had taken place more than five years before I, Peter Lazes, started to work in Newark, New Jersey, I could still smell the smoke of the burned-out buildings on Central Avenue from my office at New Jersey Medical School.

It was as if that uprising had just ended when I started my new job, developing a community psychiatry program for the patients at Martland Hospital, the large city hospital served by the medical school’s interns and medical residents. Most of the stores on Central Avenue had remained untouched since they were set on fire during the massive civil response to Dr. King’s murder. Promises made by Mayor Kenneth Gibson, the first black mayor of any major northern city, to rebuild Newark and to provide better healthcare services for its citizens, remained unfulfilled. Community activist Amiri Baraka responded to this failure with censure and disappointment, stating that Gibson’s attention was primarily focused on “the profit of Prudential, Port Authority, and huge corporations . . . while the [community] residents were ignored.”1

Eventually, New Jersey Medical School’s departments of Community Medicine, Internal Medicine, and Psychiatry began to hire practitioners like me to work with the mayor and with community groups to improve healthcare services for Newark residents. I found that by focusing on what patients were experiencing as they waited for and received clinic or emergency care, and by listening to observations of the staff who helped them— from laboratory staff to receptionists, nurses, LPNs, aides, and Emergency Department (ED) physicians—I could assist in devising a care system that worked better for all involved. Ever since then, I have spent my career devising methods to help frontline staff, workers, and administrators collaborate on improving the systems to which they devote their lives.

As this book approaches publication, the COVID-19 pandemic has been escalating daily around the world. The method that we espouse here is thus particularly relevant. Hospital staff have an imperative need to be involved in ordering equipment, setting up isolation areas, and determining staff ratios in order to keep themselves and their patients safe.

The Growing Chasm between Administration and Frontline Staff

From 1980 to 2016, I was a member of the faculty at Cornell University in the School of Industrial and Labor Relations. This position provided me the opportunity to consult with a variety of organizations, helping them to keep jobs in the United States while improving working conditions for their employees and the quality of their products and services. For the past 20 years, I have focused particularly on healthcare systems as a researcher, educator, and consultant to medical centers and nursing homes from New York City to Los Angeles. These experiences have made me aware of practical and effective methods that can improve healthcare services in our country.

My work in Newark from 1972 to 1978 brought me into early, intimate familiarity with the challenges facing urban healthcare and mental health treatment systems. Sadly, 40 years later, I continue to witness our healthcare delivery systems—the organizations of people, institutions, and resources delivering healthcare services to meet the needs of target populations—being plagued by the same struggles, and still routinely producing poor patient outcomes at high cost. To a large extent, this arises from patients’ limited access to adequate preventive and diagnostic care and from a lack of integrated patient services, especially for those with chronic, stigmatized, or complex conditions.2 These problems persist in large cities, but the systemic difficulties also affect rural and suburban communities, with rural areas especially afflicted by the scarcity of operating hospitals and physicians. I have noticed that fragmentation of care tends to go hand in hand with an alienated staff and with an administration that focuses less on patients and their needs and more on the workings and demands of an institutional hierarchy. Indeed, the growing need for hospital administrators to focus almost totally on insurance reimbursements and on meeting state or federal regulations has led to a growing chasm between them and the clinicians who directly provide patient care within many organizations.

This chasm has led to an increasing experience of frustration and even despair among those nurses, physician assistants, and doctors who care for patients. Ross Fisher, whose internal medicine practice centered on the outpatient care of patients with complex chronic diseases, describes this tragic situation: “From everything I read and hear about, I should be one of the most sought physicians to meet today’s patient population needs. But our current broken healthcare system fails to respect and accommodate the requirements necessary to succeed in managing these challenging patients, and the reality today is that I am marginalized and diminished in capacity by forces removed from my influence.” He describes those forces especially as including the fact that in most settings, “the power to dictate how much time a provider spends with a patient is divorced from the primary . . . caregivers.”3 In addressing this dilemma, Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker stated, “Our system should reward clinicians who invest in time and connection with patients and families.”4

No matter what form of payment is used so that all Americans have access to healthcare services—whether one has insurance through his or her employer, exercises a public option, or is enrolled in Medicare for All—we need to restructure our delivery systems and pay for clinicians to have sufficient time with their patients. As it currently stands, in most U.S. hospital and outpatient settings, caregivers have become increasingly despairing about the degree to which their time with their patients is managed by administrators and insurers. As they mourn their ability to be clinically effective, this dramatically affects their patients’ healthcare experience.

How the System Disconnects Clinicians from Patients

I, Marie Rudden, MD, have worked as a practitioner in multiple medical settings for the past 50 years, and for the past 10 I myself have suffered from two complex chronic illnesses (systemic lupus erythematosis and Sjogren’s syndrome), an experience that has illuminated the shortcomings of the American health-care system quite vividly and personally for me. As clinicians in even excellent tertiary care institutions have little time allotted for patients with complex conditions, I have had to become my own advocate, pointing out aspects of my history about which my doctors have little time to inquire, and communicating test and consultation results myself to each of the specialists involved in my care. As a practicing physician, I am prepared for this task. However, I have seen firsthand among my own patients with chronic illnesses how bewildering this process is for those without a medical degree. I routinely call their multiple specialists in order to understand my patients’ diagnoses and treatment strategies, and then translate what I find to answer their questions.

I have been able to do this because I am in the minority of remaining physicians who have practiced privately and thus control their own schedules—a sadly vanishing breed, due to the increasing, expensive incursions into practice by insurers and regulators starting in the late 1980s, which have driven physicians into working within group practices and larger hospital systems. These incursions began with the limitation by Medicare on physicians’ charging for more than one intervention per day, which keeps doctors from visiting their patients whom they have just admitted to the hospital, to follow up on their care. It prevented me from seeing patients with psychiatric emergencies, first by themselves and then later in the day with their families, whose support they required in order to avoid hospitalization.

This situation accelerated with the spread of HMOs, which restricted many other aspects of patient care. I well remember an untrained “behavioral healthcare representative” instructing me to refer a quite troubled patient to an online support group rather than approving her continued treatment with me. It took hours of my time to appeal this foolhardy decision.

Further, since the enforcement of a universal requirement that clinicians record every visit through an electronic medical records system, primary care doctors now spend nearly two hours typing into these records for every hour they spend in direct patient care!5 The time these records systems require drives clinicians away from fully listening to their patients and from communicating with other specialists.6 As one nurse reported, “I didn’t become a nurse in order to collect data.”7 While electronic records were partially intended to help coordinate patient care through the sharing of information from clinical visits, lab tests, and procedure results, their use has become the bane of most clinicians’ work lives. Most EMR programs require them to follow a rubric that often fails to include central issues addressed within their patient visits. Our healthcare system must be reorganized so that clinicians have enough time and resources to practice more humanely and effectively without such intrusions.

The Purpose of This Book

As both of us have been occupied in our careers with what makes organizational systems more effective and have observed the central role of frontline staff and caregivers in this effort, we offer methods for restructuring healthcare systems in a way that makes collaboration and active communication among administrators, medical staff, and patients a key value. This book explores exactly what it takes to effectively engage staff and providers in improving the patient care shortcomings within their institutions. We do this by presenting case studies of institutions that have successfully implemented major systemic changes in this manner, by reviewing research findings and outcomes, and by conveying the direct words and experiences of staff who have participated in changing their healthcare organizations.

We offer several avenues toward redressing care system shortcomings but focus particularly on the use of Labor-Management Partnerships to restructure care as it is currently offered. Such partnerships are based on a cooperative engagement among administrators, providers, and staff; offer contractual protections for each group; and include defined methods for initiating and overseeing unit-based, departmental, and system-wide changes. The outcome of an effective, well-resourced Labor-Management Partnership can be more meaningful work for employees, greater workplace morale, increased awareness for administrators of flaws in their operating system, improved patient care, and cost savings.

Throughout this book, we examine questions such as: How can the knowledge and communication gaps between administrators and those who offer care be overcome in our healthcare systems? What roles do management and healthcare union leaders (when applicable) need to play to capture the knowledge and firsthand experience of their frontline staff in making decisions about the practice of patient care? What interventions are most useful for assisting them in turning their ideas into workable proposals? What processes and structures best accomplish effective changes within a given healthcare system? And what are the challenges that arise in involving frontline staff and their unions, when present, in redesigning their healthcare delivery system?

We have shaped this book around the specific methods that healthcare systems can employ in order to enlist their frontline staff in diagnosing and rectifying difficulties in providing high-quality patient care. This book not only is a manual detailing what can be achieved when frontline staff have a direct voice in controlling their practice environments, but also was written to provide a method for accomplishing transformative changes in how our hospitals and outpatient clinics work.

All Americans deserve and should have access to high-quality, affordable healthcare services delivered by professionals who know them and who have sufficient time and resources to care for them.

Why Healthcare Systems?

Much has been written about the need for healthcare reforms in America. Governmental attention is usually directed to increasing citizens’ access to insurance, to rewarding institutions for positive outcomes, or to penalizing institutions for practices that fall short—for example, for frequent and early hospital readmissions. This top-down approach has been valuable in focusing hospital and systems administrators on essential bottom-line markers of effective treatments. Such approaches, however, need supplementation by finer-gauged methods for identifying and addressing the service gaps particular to each institution.8

The participation of frontline staff in identifying areas of concern, and in creating and, most important, implementing changes that will transform our current systems, is vastly underutilized, even as it has been shown to assist hospitals and health systems in becoming more efficient and delivering higher-quality outcomes. One study by Anita Tucker at Boston University, using data from 20 hospitals, documented that frontline staff proposals for improving patient safety were more effective than those originally offered by the institutions’ managers and also led to more effective utilization of staff time and efforts.9

North American hospital administrators are rarely taught in business, medical, nursing, or public health schools how to meaningfully engage with clinicians or caregiving staff or with the unions that represent healthcare workers.10 To the detriment of all, clinicians and other frontline staff are essentially told, “Keep your thoughts about patient care and the work environment to yourself. We know what’s best to keep this institution afloat.” This situation is particularly unfortunate in healthcare organizations, in which nurses, aides, pharmacists, dietary and cleaning personnel, physician assistants, and physicians can all observe problems in care delivery, in cost excesses, and in the uses of technology, and can contribute to solving them. When implemented effectively, frontline staff participation creates a cogenerated process,11 weaving together the knowledge and skills of frontline staff and management to result in a stronger organization. We offer practical examples of how to implement and sustain an effective participatory process, as well as an analysis of the challenges in undertaking such a change process.

Focusing this book on healthcare organizations is also particularly important, as this is a growing sector of our national economy, and one that elicits significant concern due to skyrocketing costs and limited access to high-quality services. Health-care costs now consume over 18 percent of our current gross domestic product (GDP),12 and the healthcare sector is expected to generate more new jobs than most segments of the economy, at least through 2026.13 The need for more coordinated, cost-effective services is also growing due to an aging population with patients who may have complex, intersecting illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, autoimmune disorders, pulmonary diseases, and cardiac diseases.

Since healthcare services are mostly provided directly to patients on-site, aside from radiology and pathology, they cannot be outsourced,14 which is a cost-cutting strategy used in other sectors of the U.S. economy. Thus, healthcare organizations must find different ways to cut costs while also providing high-quality-of-care outcomes. It makes intrinsic sense for frontline providers and staff, who daily witness the aspects of their system that may not be cost-effective, to be enlisted in a joint effort toward cost containment.

The Importance of Labor-Management Partnerships

In the United States, unions represent 20.7 percent of the healthcare sector’s workforce, a statistic that is increasing15 just when union membership is shrinking in most other segments of our economy.16 Our focus on employee participation within healthcare needs to take this fact into account. Happily, many unions representing healthcare workers17 have themselves become increasingly sophisticated in working with healthcare administrators to create joint labor-management participation processes.

Modern healthcare organizations—outpatient clinics, inpatient settings, nursing homes—interface constantly with an array of insurance companies, each with its own set of cost-monitoring practices, as well as with state and federal regulatory agencies. As stated earlier, the need for these organizations to stay on top of the ever-changing regulatory and reimbursement processes has led to an increasing stratification within them, with CEOs, CFOs, and whole administrative branches devoted to budgeting and regulatory issues rather than to what happens within the hospital: patient care.18 In fact, from 1975 to 2010, “[t]he number of healthcare administrators increased 3,200 percent. There are now roughly 10 administrators for every doctor within United States healthcare systems.”19 In such top-heavy organizations, administrators have become too far removed from the daily process of patient care to effectively manage all the issues that arise within their complex medical settings.20

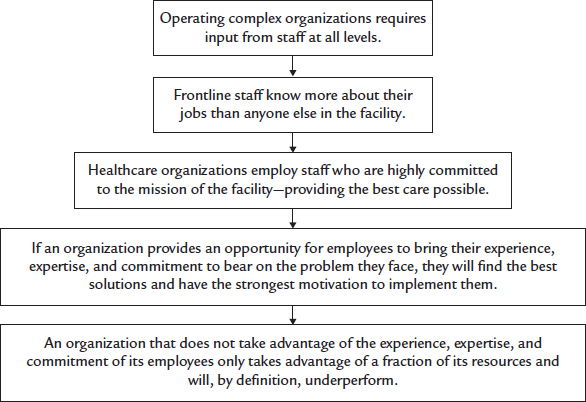

Complex organizations, as a rule, face real difficulty in making changes effectively and efficiently due to their having to face multiple variables, often occurring within siloed departments. It has become a common understanding in in the organizational studies literature that in complex institutions, the flexible but structured involvement of all key stakeholders is required to achieve an optimal result.21 For healthcare organizations, this means that the staff who interact with and directly care for patients must be involved in decision-making processes—in analyzing both care-delivery shortcomings and opportunities for improvement. Working together, administrators and frontline staff can claim responsibility for envisioning, researching, and implementing the changes necessary to create a high-functioning complex organization devoted to caring for sick patients (see figure 1). At the unit and departmental levels especially, this involves consultation and knowledge sharing with all contributors to their particular mission.

Figure 1. Healthcare Facilities Are Very Complex Organizations

The Labor-Management Partnership approach has emerged as especially useful in formalizing processes through which frontline staff can contribute to improving their workplaces while also making their own working lives more meaningful. The approach creates a clear process for frontline staff and administrators to jointly identify and solve patient care problems, make work decisions, and implement their solutions. We focus in this book on defining and demonstrating the use of this strategy.

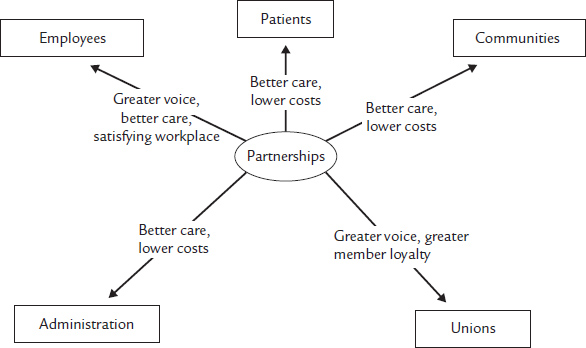

Examples of the use of Labor-Management Partnerships to structure a shared decision-making process among the organizational stakeholders are provided throughout the book. Within such partnerships all stakeholders, including patients, contribute to and benefit from this process (see figure 2).

One example of a Labor-Management Partnership, described in detail in chapter 4, concerns the joint effort of administrators, nurses, physicians, and other staff in one hospital to respond to a series of sudden deaths that occurred within their cardiology unit over a short time period. The hospital administration’s initial response to this crisis was to penalize nurses who had not responded quickly enough to the patients’ cardiac monitors. A more forward-thinking response occurred when the hospital’s Labor-Management Partnership created a joint task force composed of clinical personnel on the unit and their departmental administrator to study what had actually led to these errors. As a result of their joint analysis of the crisis, the hospital eventually purchased a more effective cardiac monitoring system, and various practices surrounding the transport of monitored patients and the assignment of nurses to high-risk patients were instituted. As a result, no more such deaths occurred in subsequent years. The administration alone had not been aware enough of the practical difficulties in caring for and monitoring such patients to be able to arrive at such a solution by themselves.

How This Book Is Organized

Although our book focuses on the importance and application of healthcare Labor-Management Partnerships to improve patient outcomes and control healthcare costs, the basic principles presented can and should apply to other economic sectors as well. From the Ground Up begins with a brief review of employee participation activities and Labor-Management Partnership practices as they evolved in the United States (chapter 1) and in Europe (chapter 2). These histories are presented from the vantage point of a practical analysis: What were the goals of such activities? How were their processes structured? What sorts of problems did these activities attempt to address? What outcomes were obtained? These chapters orient the reader to the particular practices of Labor-Management Partnerships, which can deepen and extend earlier employee involvement activities.

Figure 2. Healthcare Partnerships Can Benefit All Stakeholders

Chapter 2 also highlights the critically important connection between worker participation and increased civic participation among frontline workers, an issue amplified in chapter 8. This is crucial for our country today, given the alienation too many citizens feel toward their local and national government.

Chapter 3 presents specific core practices for developing and sustaining a viable Labor-Management Partnership. Two extensive case studies are employed to illustrate these necessary practices, which include creating a social contract between labor and management about their mutual goals, with protections for each side and a clear decision-making process; developing educational activities for both staff and senior leaders about the need for, and processes involved in, change; improving overall labor relations within the organization; using sector strategies to find solutions already in use in other venues; and documenting results of the change processes.

Chapter 4 describes structures for effectively implementing frontline staff participation within Labor-Management Partnerships. Unit-based and departmental approaches can achieve both process and quality-improvement outcomes within current work systems, while the Study Action Team approach can create new work structures that address cost-saving and quality improvement throughout the organization. Vignettes from both healthcare and manufacturing partnerships present the pros and cons of each of these approaches, providing a broad understanding of which form of partnership might best suit a particular workplace.

Chapter 5 details ways in which work group leaders can respond to departures from a work focus in their teams and suggests approaches to problems that can arise in teams when members occupy different places in the organizational hierarchy or come from different cultural backgrounds.

Chapter 6 details how labor unions can foster a worker participation process, offers advice to union leaders who are contemplating engaging in such activities, and describes the risks and benefits to labor unions for engaging in such activities.

Chapter 7 offers suggestions for healthcare leaders seeking to expand existing Labor-Management Partnerships. The first section of this chapter focuses on two unique approaches to enlist greater frontline staff participation within the existing work systems; the second section describes a method borrowed from the technology industry for launching new Partnerships that significantly transform current delivery systems. We also discuss the need for Partnerships to include patient as well as staff input in their proposals for systemic change and suggest a method for the Partnerships to interface with insurance companies regarding reimbursement changes.

Chapter 8 summarizes the successes of Labor-Management Partnerships but also takes a close look at what has happened when existing Partnerships that offered initial promise were not sustained. We describe preventive measures based on these findings. We also document research on the increase in civic participation among workers and staff who participate in Labor-Management Partnerships, a finding that is of crucial importance to sustaining our democracy.

In the epilogue, we reprise the importance of worker participation as a critical process for improving healthcare outcomes. We also emphasize the central concepts and strategies offered in the preceding chapters, most of which are highly practical. We summarize the state of our current healthcare “system” in which chaotically intertwined for-profit systems entangle clinicians’ abilities to deliver adequate care to their patients. Finally, we issue a call for collective action to all healthcare administrators, professionals, and frontline staff to challenge these systems. We outline ways in which the corporations that currently hold patient care systems hostage can be pressured, through political and staff group actions, to resurrect the value of “first, do no harm” in treating patients.

In sum, this book will inform you about the historical development of approaches for engaging frontline staff in job redesign and in the creation of more effective organizational systems. The book gets you under the covers, so to speak, exploring what it really takes to effectively initiate, implement, and sustain employee involvement activities. It demonstrates how Labor-Management Partnerships particularly can help organizations to evaluate the effectiveness of their current systems and to design more functional structures. We emphasize too the importance of establishing collaborative leadership processes to engage and sustain employee participation efforts.