6

Planning Approach for Any Group

WHO DOES WHAT, BY WHEN?

Plan your work and work your plan. Let’s begin your journey with planning (novel idea?).

For Strategies, Initiatives, Projects, Products, and Teams

What is the difference between a strategic plan, a department plan, a product plan, a project plan, a team plan, and so on? Primarily, scope. The word “plan” can be defined with three words (preferably five), namely “who does what” (by when)—that’s a plan. The same logic extends throughout an organization. Every business group needs answers to the nine questions listed in the “Basic Planning Agenda” section that follows. This chapter shows you how to facilitate consensual agreement around those answers for any group.

Modify the following Planning Approach to define organizational direction when your group needs to build consensus around its priorities and initiatives. A robust Planning Approach defines vision factors, success measures, actions, and responsibilities. Further, the Planning Approach also does the following:

- It becomes a compelling road map for future decision-making. The Mission anchors decisions, the Vision inspires decisions, the Values discipline decisions, and the strategic plan articulates decisions, highlighting Actions that need to be promoted.

- The Planning Approach describes a group’s intent: who it is, where it is going, what to do to get there, and when the Actions will be accomplished.

- The Planning Approach may describe a situation, including problems or opportunities, what to do about them, and consideration about associated assumptions and constraints.

- The Planning Approach may describe the strategy, tactics, or activities along with roles and responsibilities for fulfilling products, projects, and other initiatives.

- The Planning Approach requires you to modify and reinforce your session with team-building exercises, creativity exercises, or both, as necessary.

- The Planning Approach suggests that preparatory conversations should focus on the people, personalities, and conflict issues, more than focusing on products, process, or technology content.

PLANNING DELIVERABLE

While a planning session’s input begins with why a group exists, the output documents what team members agree to do. A primarily narrative document, plans may be augmented with . . .

- Supporting graphics or illustrations that represent the Mission and Vision (chapter 6),

- A numerical matrix for Quantitative TO-WS Analysis (chapter 6),

- An iconic or numeric Alignment matrix (chapter 6), and

- An Assignment matrix (chapter 6).

BASIC PLANNING AGENDA

- Launch (chapter 5)

- Mission (why are we here?)

- Values (who are we?)

- Vision (where are we going? How do we know if we got there or not?)

- Success Measures (what are our measurements of progress?)

- Current Situation (where are we now?)

- Actions (what should we do?—from strategy through tasks)

- Alignment (is this the right stuff to do?)

- Roles and Responsibilities (who does what, by when?)

- Communications Plan (what should we tell our stakeholders?)

- Review and Wrap (chapter 5)

VISUAL AIDS TO ANTICIPATE

- Meeting purpose, scope, and deliverable in writing—handouts or large-format paper for in-person meetings and handwritten or handheld artifacts for online meetings

- Basic Agenda, easily accessible and preferably included in the pre-read, as well as additional handheld artifacts for online meetings, such as definitions or legends

- Definitions for each of the key terms, especially Mission, Values, Vision, and Key Measures—perfect for a slide or screen share because slides are good for transitory material that comes and goes, as with definitions or legends

- Quantitative TO-WS Analysis spreadsheet (Excel) (chapter 6)

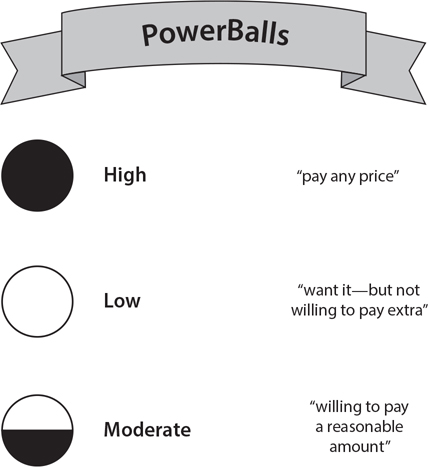

- PowerBalls (chapter 7) and Prioritization (chapter 7) legends, posters, or handheld artifacts for online meetings1

- Ground Rules (chapter 4), readily available as posters or handheld artifacts

- Blank Refrigerator (Parking Lot) and Plus-Delta (chapter 5)

COMMENTS

Planning workshops require more facilitation skills because of personality challenges and other biases. Carefully control your operational definitions for critical terms (Mission versus Vision, goals versus objectives, and so on) and how they fit together to form a strategic or other type of plan before launching your planning session.

Observe that in the Basic Agenda I have used a lighter gray type for traditional terms like Mission and used black type to emphasize the critical words (why do we show up?)—the primary questions being answered during each Agenda Step.

NOTE: Much confusion exists about the difference between Mission and Vision. Here’s why. Academic textbooks typically follow the sequence I use, including defining the terms by the questions being answered. The military-industrial complex also sequences the questions in the same order I use but defines the associated terms differently.

For example, the US Armed Forces define Vision as the answer to the question, “Why do we show up?,” and they define Mission as the answer to the question, “Where are we going?” Professional meeting designers remain agnostic and may use either sequence based on what is normally used by the culture being served. Keep in mind that the sequence of the questions does not change for either group. Both cultures need to know why they show up before they talk about where they are going.

For purposes of this book, Mission will be defined as “why we are here,” and Vision will be defined as “where we are going.” I leave it up to you to make the necessary adjustments based on the culture of the organization for which you are facilitating.

This Basic Planning Agenda can be used at any level in the holarchy—anytime a group of people needs to define who does what. If you are facilitating strategic plans for organizations, business units, and significant departments, proceed with the agenda as shown, including Mission, Values, and Vision.

For other types of teams, including team charters for products and projects, substitute the Purpose Tool (chapter 7) instead of using Mission, Values, and Vision. Either tactic creates a sense of direction upon which you build the Key Measures such as objectives and goals. After completing either the Mission, Values, and Vision or the Purpose Tool, every team needs answers to questions from the other Agenda Steps, namely:

- What are our measurements of progress to know we are reaching our vision?

- Where are we now?

- What actions should we promote to ensure reaching our goals and objectives?

- Is that the right stuff to do?

- Who does what, by when?

- What should we tell our stakeholders?

RIFFS AND VARIATIONS

The detailed instructions and procedures that follow may be easily modified to accommodate your culture and preferences. There is more than one right way to facilitate any Planning Approach. More important, however, there is a wrong way. The wrong way surfaces when you don’t know how to use or have not fully prepared a procedure.

NOTE: I will illustrate the Planning Approach Agenda Steps using a fictitious greenfield company called THRIVE LLC. THRIVE provides for-profit products and services to residential households, intending to make household and family activities and resources easier to manage. Occasionally, I will also reference the sport of mountaineering. Either may be used as an analogy to illustrate deliverables from the Agenda Steps covered over the next few dozen pages.

Explanation by Analogy

When explaining the agenda during the meeting Launch, provide a parallel path of change via analogy. Analogies help protect your neutrality while bringing to life the sequence and connections of Agenda Steps.

The Mission Agenda Step contains a unique challenge because Mission ad-dresses why we show up. We could show up for any reason we want. The reason for showing up establishes the foundation for your analogy, helping you link each Agenda Step back to the meeting deliverable. I encourage you to work with an analogy around which you have a personal passion.

For example, if you love baking, the analogy could be a designer cake. If you love scrapbooking, the analogy could be an award-winning scrapbook. Or, in the analogy chosen for table 6.1, we love mountaineering, and therefore reaching the summit.

Refer to your analogy to help explain the purpose of each Agenda Step. The analogy guides smoother transitions as to why the Agenda Steps are listed in the sequence shown. Although I picked a sport (some people are turned off by sports), I selected a gender-neutral, generic sport with a clear deliverable, reaching the summit.

Please accept my apologies in advance for the upcoming “mixed metaphor” because I will also use THRIVE LLC for examples, to provide analogous explanations with “business-like” conditions.

Pre-session Survey or Online Poll—for Strategic Planning Only

For strategic planning especially, assess a composite view of answers to the following six questions (see table 6.2). Gauge your group in advance so that you can better estimate how much you might get done, how quickly (or not), and how much resistance you will encounter.

Liberally modify the questions yourself and add others that establish a feeling for the culture. I strongly encourage you to keep participant contributions anonymous. Aggregate results and display them in a chart when sharing your findings.

1. Launch (Introduction) Agenda Step

Use the seven-activity sequence for Launch (chapter 5). Remember that the Launch is the “preachy” part for a meeting facilitator. My own Annotated Agenda for a Launch is always around three pages. If you want to rehearse anything, try explaining the white space behind your Agenda Steps—why are they there? Contextual control provides a terrific opportunity to develop confidence among your participants.

Table 6.1. Mountaineering Analogy

Agenda Step |

Corresponding Analogy |

Mission Why do we show up? |

We choose to show up because we love mountaineering. |

Values Who are we, and how do we treat one another? |

We could be young and vibrant with no cash, or more mature and experienced with lots of money. What do we carry with us? Young people have ropes and value rappelling. More mature people have Sherpas who carry ladders, among other stuff. |

Vision Where are we going? |

Which peak are we going to ascend? Young people may choose the south peak because they don’t have much time. Mature people may choose the north side with switchbacks that enable them to use their ladders and stop for comfortable breaks. |

Key Measures What are our measures or indicators of progress in reaching the Vision? |

There are three types of criteria: SMART—Be at 5,000 meters suspended in our sleeping bags before the storm blows in at 3 p.m. (objective). Fuzzy—Get some nice photographs when we reach the summit (subjective or aspirational such as a goal). Binary—Did we reach the summit or not (critical consideration)? |

Current Situation What is our current situation of things we control and do not control? |

TO-WS analysis (showing the youthful mountaineers): Externally Controlled External Threat—avalanche External Opportunity—a “break” in the weather Internally Controlled Internal Weakness—few supplies Internal Strength—stamina and flexibility |

Actions—What to Do Given our Current Situation, what do we agree to do to reach our Key Measures placed as milestones to ensure we reach our Vision? |

Young people—They are going to rappel up the south side of the face of the mountain to quickly reach the summit so that they can return to base camp before they run out of supplies. |

Alignment Are those the right Actions and enough Actions to ensure we reach or exceed our Key Measures? |

Do they have enough rope? If the young people are rappelling 100 meters but only have 50 meters of rope, let’s find out before they take off so we can adjust either the path or the amount of rope. |

Assignments Who is doing What? |

Who is carrying the rope? |

Communications Plan What do we tell the world about what we completed here? |

Phone home before they make their ascent in the morning when the weather is predicted to be calm. |

Table 6.2. Pre-session Survey for Strategic Planning

Among employees, what is the balance between anxiety and hope? |

||||||||

Mostly |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Mostly anxiety hope |

How does senior management’s point of view about the future compare to that of competitors and other industry experts? |

||||||||

Conventional |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Distinctive and reactive and far-sighted |

To what extent are we engineering the present or designing the future? |

||||||||

Mostly an engineer |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Mostly an architect or a designer |

What amount of our efforts focus on catching up versus setting up our own future vision? |

||||||||

Mostly a |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Mostly a rule-taker rule-maker |

What amount of our efforts focus on catching up with competitors versus building new industry advantages? |

||||||||

Mostly |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Mostly catch-up new stuff |

Which issues absorb senior management’s attention? |

||||||||

Re-engineering |

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

Regenerating core processes core strategies |

Note: If your marks lean to the left or in the middle, your organization may be spending too much time preserving the past and not enough time and energy strategizing a new future. |

||||||||

NOTE: For multiple-day workshops, cover the same items at the start of the subsequent day. Additionally, review content that was built the preceding day or days and reinforce how that relates to the progress being made completing the deliverable.

Before you begin your meeting Launch, have your physical or virtual room set up to provide a visual display of the meeting purpose, scope, and deliverable. Let me repeat that if you do not know what the deliverable looks like, then you do not know what success looks like.

INTRODUCTION PROCEDURE

Follow these activities in this sequence for a robust start:

- Introduce yourself and stress the importance of meeting roles. Stipulate how much money or time is at risk if the session fails.

- Unveil your meeting purpose, scope, and deliverable. Seek audible assent from all. Ensure that all the participants can support them.

- Cover “administrivia” to clear participants’ heads from thinking about themselves, especially their creature comforts. Explain where to locate lavatories, fire extinguishers, emergency exits, and other stuff they may be thinking about. Provide a check-in activity or Icebreaker, especially for online meetings and workshops.

- Carefully explain the logic behind the sequence of your Agenda Steps. Explain how Agenda Steps relate to one another. Link Agenda Steps back to the deliverable so that participants see how completing each Agenda Step provides content that helps complete the deliverable.

- Share Ground Rules (chapter 4). Supplement your narrative posting of Ground Rules with audiovisual support, including humorous clips, but keep them brief.

- For a kickoff, have your executive sponsor explain the importance of participants’ contributions and what management intends to accomplish. Do not allow the executive sponsor to take more than five minutes.

2. Mission or Charter (Why Are We Here?)

Mission defines the why of any business area or organizational scope. For me, the definition is brief, like a slogan, so that it is never forgotten, Mission represents an action-oriented expression of an organization’s reason for existence. When explaining, link back to your analogy.

Mission expresses why the participants, or group, or organization show up—the purpose and reason for their existence.

The Mission expression provides the foundation upon which other Planning Approach Agenda Steps are built. Each subsequent Agenda Step refers to the Mission expression (as purpose), ensuring harmony with the Mission of the group and organization. Mission documents why an organization exists, vitally linking it to subsequent Agenda Steps.

HINT: Mission expresses why. Why are we here? Why are we doing this? I recommend a concise expression that could fit on a bumper sticker or T-shirt. Servant leaders strive to ensure that Mission balances both the head (will), the heart (wisdom), and the hands (activity).

WHAT DOES A MISSION EXPRESSION LOOK LIKE? YOU DECIDE

You need to carefully determine what does your deliverable look like when you are DONE. Will it be a sentence, a paragraph, or a bumper sticker? Will it be brief and snappy like an axiom, or fully described? There is no single right answer; the wrong answer is not to know.

The following lists aggregate comments made by dozens of “experts” on strategic planning. Clearly, the characteristics of Mission expressions vary tremendously. Use the following and embrace what resonates with you:

Characteristics

- – Connected to deepest interests

- – Inspires commitment

- – Stirs up passion

- – Uniquely a description of why they show up now (Vision deals with the future, or where)

Clarity

- – Not fuzzy (avoid words that mean different things to different people such as “excellent” or “best”)

- – Sufficiently clear to guide people in day-to-day decision-making

- – Capable of being understood by a 12 year old

A Mission expression is not . . .

- – What the organization does

- – How the organization does that

- – Where the organization is going

Length (if people can’t remember a Mission expression, it serves only as a wall decoration)

- – No more than one sentence long

- – Short, clear, and usually less than 14 words

- – Short and sharply focused

- – If possible, 10 words or less

Ease of recall

- – Easy to remember

- – Easily recalled and recited, even if one is held at gunpoint

- – What the organization wants to be remembered for

STANDARD MBA QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER

Next determine the questions you deem most appropriate to have your group answer. The Mission expression traditionally distills answers to the following, textbook MBA prompts:

- Who the organization is and its role in the market environment

- Scope (boundaries) of operations

- Distinctive or unique characteristics—core competencies

- The organization’s customers or stakeholders

- The organization’s products or services

Other academic styles apply similar logic:

- Who are the targeted customers

- Need of the customers or opportunities being fulfilled

- By the primary products, services, or other value-add activities performed

- That serve a clear purpose and generate specific benefits

- Unlike competitor or competitive alternative being displaced

- Unique characteristics and differentiators include . . . 2

FOR AN EXTRAORDINARY MISSION EXPRESSION

Building a Mission expression can also be fun because you can use any questions that you think will benefit your group. Think about what you want your group members to know about one another, their situation, their conditions, and their stakeholders.

To avoid the “common deliverable” that makes many companies sound exactly like their competitors, consider the alternative questions that follow. Especially for team charters and other planning efforts, find the passion, rather than using the textbook MBA questions (everyone wants to grow and provide quality service). What truly makes your group unique? Why do they really show up?

Find the passion:

- Nothing else can _______.

- We are famous for _______?

- What allows us to take market share away from them?

- What are we most proud of about _______?

- What do you want others to say about _______?

- What is it about our competitors that allows them to take market share away from us?

- When the lights go out at night, people know _______?

- Whom do we aspire to be in terms of the market? In terms of performance?

- Why would the world be a less rich place if _______ disappeared?

You can modify questions to work with any group. Michael Barrett, of Resonance LLC, uses the following questions with boards of directors of nonprofits. He emphasizes that in one meeting, when directors shared their illustrations with one another, some were moved to tears.

- What do you bring to this organization?

- What do you need from this team?

- What is one event that fundamentally shaped your life?

- What legacy do you want to help create through this organization?

Other topical areas you might explore include these:

- Defining moment

- Greatest challenge for this group

- Greatest success for this group

- Moment of pride

- Worst fear

To facilitate a Mission, I use Brainstorming, Coat of Arms, and Breakout Teams Tools, whose explanations follow. After the next Agenda Step (Values), we will look at the Scrubbing, Defining, and Categorizing Tools.

DETAILED PROCEDURE

Display, distribute, or post the questions that you have selected.

- Use Brainstorming (next section) to build input for the group’s Mission expression.

- Use Breakout Teams during the Listing activity (explained after Brainstorming).

- Have each team use the Coat of Arms (explained after Breakout Teams) to answer each of your questions.

- Pull the teams together using the Categorizing Tool (explained in the next Agenda Step—Values) to analyze input and converge upon consensually agreeable output.

- Assign the output to two or three volunteers who take time after the meeting to write down candidate Mission expressions that can be reviewed by the entire team at another session.

- Allow time and gestation for the draft inputs to grow into a final expression everyone supports.

SAY WHAT?

Begin to appreciate the circuitous challenge of meeting design. It would be much easier to forget structure, sit around, and have a discussion. But how’s that working out for you?

- I am suggesting that you use a Tool nested within a Tool that is nested within a Tool that relies on an additional Tool . . . Huh?

- Coat of Arms is nested within Breakout Teams, which is nested within the Listing activity of Brainstorming.

- Output from Listing provides input for the Analysis activity, such as the Categorizing Tool.

- Categorizing may rely on Scrubbing, Defining, and Prioritizing—all nested within the Analysis activity of Brainstorming.3

- Say what?

The meeting designer’s life is never easy. I could go even further and use PowerBalls or Perceptual Mapping (Tools for prioritization) to prioritize input for the Mission expression, but for now, let’s keep it painless; PowerBalls and Perceptual Mapping are explained in chapter 7.

FOR MISSION EXPRESSIONS ONLY

The Coat of Arms Tool may be used for the Listing activity of Brainstorming when there is more than one question to answer. However, while especially useful for Mission expressions, time box (set a time limit) a Mission expression. Mission expressions can be highly emotional—so do not expect them to conclude smoothly or quickly.

Ask for volunteers to take time after this session concludes and return at some future time or date to share some expressions for all participants to consider. When reconvening, try to post the original Coats of Arms to stimulate and remind participants about their original answers.

COMMERCIAL EXAMPLES OF MISSION EXPRESSIONS

It’s difficult to distill the passion and verve of any group, organization, or team into very few words. However, by my standards, the following (at some point in time) reflected Mission quite well:

- Caribou Coffee (seven words): To be the best neighborhood gathering place.

- Cirque du Soleil (nine words): Invoke the imagination. Provoke the senses. Evoke the emotions.

- Dunn’s Local Newspapers (one word, three times): Names, names, names.

- Ritz-Carlton (seven words): Ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen.

- United States Marine Corps (six words): The few, the proud, the Marines.

- Noncommercial examples:

- – The golden rule is expressed with only 10 words (see the epilogue to this book for 13 versions).

- – The Peace symbol (nuclear disarmament; see figure 6.1) is nonnarrative and yet communicates universal intent about peaceful protest and mission.

Figure 6.1. Nuclear Disarmament Symbol

CAUTION: Mission expressions should be time-boxed. There are horror stories of groups that went off-site for a few days and never completed the first step of their agenda, Mission. Crafting the perfect Mission expression is not easy. Nor should it be expected during the first attempt.

Don’t hesitate to ask for two or three volunteers to take output from the initial exercise as an assignment when the session has completed. Have them go away and craft candidate Mission expressions to bring back to the group at a future session for consideration. Allow the power of gestation to work for your group. Their final Mission expression may take a few months, or longer, but continue to revisit the updated drafts until one version resonates with everyone.

CLOSURE

When you have assigned, documented, or drafted a Mission expression, and with the group’s assent, apply your analogy and move the agenda indicator4 for a smooth transition to the next Agenda Step, Values—answering the question, “who are we?”

COMMENTS

Effective meeting design is clearly not effortless—but the rest of this book will make it much easier for you. I will recommend using Brainstorming, Coat of Arms, Breakout Teams, and so on dozens of times throughout the book, so . . .

- I am not going to repeat the procedure for each Tool every time it is referenced. That would require hundreds of pages of redundant material.

- You will find an alphabetically sorted Table of Contents for Tools at the end of the book, making it easier to find the detailed explanations and procedures for each Tool.

Brainstorming Tool

A frequently abused and nebulous term, “brainstorming” is right up there with “process,” “system,” and “user experience.” Brainstorming is the means to an end. It is not a verb. You cannot “brainstorm” something if you are using the technique of the creator, Alex Osborn.5 You can, however, list, analyze, and then decide—or, using terms preferred by academics, diverge, analyze, and converge. Therefore, the trichotomous term (sorry) “brainstorming” should never be listed as an Agenda Step. To be successful, you must clearly envision the output from your Agenda Step before you apply Brainstorming activities.

Table 6.3. Trichotomy of Will, Wisdom, and Activity

Trichotomy |

Will |

Wisdom |

Activity |

Brainstorming |

List |

Analyze |

Decide |

Transformation |

Thought |

Word |

Deed |

Reflectionist |

WHAT |

SO WHAT |

NOW WHAT |

NOTE: The trichotomy unfolds transformation from the abstract to the concrete. Note the similarities of three different Tools in table 6.3. Brainstorming may be used to develop anything. Brainstorming intends to give us more information to use in a shorter amount of time by leveraging the power of groups. However, lists by themselves can be frustrating, since consensual answers never simply “pop out” of the wall or screen (flat-land).

Successful Brainstorming depends on thorough analysis. Creating, typing, or writing down lists is the easy part. The hard part is understanding what you are going to do with the list—the hard part is the analysis.

When facilitating, the Analysis and Decide activities provide significant challenges. Yet most people equate the term “brainstorming” with the Listing activity alone, and that is not Osborn’s definition, intent, or meaning.6 Osborn created the term in 1953, describing it as “a structured way of breaking out of structure.”

A THREE-ACTIVITY PROCEDURE

Brainstorming requires three discrete activities. Each could represent separate Agenda Steps:

- Listing or diverge (describe Agenda Step by title of the list)

- Analyze (describe Agenda Step by the outputs, such as prioritization)

- Decide or converge (describe the Agenda Step by the deliverable, such as a “decision”)

1. LISTING ACTIVITY (ALSO KNOWN AS “DIVERGE”)

Quickly list candidate items—do not talk about the merits of them or, in fact, have any discussion at all. Keep the energy high. Select from the following ideation rules as appropriate. Do not, as most facilitators do, become the first violator by asking for more information about an item, requiring further definition, mentioning that “we already have that,” or starting any inquiry. As the expression goes, “Is there any part of the word ‘no’ in the rule ‘no discussion’ that you don’t understand?”

Special Rules for Listing

The first two rules specific to Listing are sacrosanct. If you monitor these two closely, you don’t need any other Listing rules. The other Listing rules below may be helpful but are only supplemental. Remember, if you start or allow any comments or discussion during the Listing activity, you are not doing Brainstorming.

- No discussion

- Fast pacing, high energy

- Supplemental:

- – All ideas allowed

- – Be creative—experiment

- – Build on the ideas of others

- – Everyone participates

- – No wordsmithing

- – Passion is good

- – Suspend judgment, evaluation, and criticism

- – Five-minute limit rule (ELMO: Enough, Let’s Move On)

Ideation Riffs and Variations

There are various activities for Listing and gathering input, such as the following:

- Breakout Teams—use separate teams to provide ideas simultaneously. Using Breakout Teams remains my clear preference since you can get more done faster. With Breakout Teams, participants provide narrative or illustrative answers to your questions.

- Surprisingly, it is easier to illustrate than narrate answers to complex questions. In person and online, groups are refreshed by breaking into smaller teams to have conversations. Plus, as you begin to Analyze, where two or more teams have offered the same or similar content, consensus arises immediately.

- Facilitator-led questions—keep in mind that you can use a support scribe(s), but if so, remind them of the importance of neutrality and capturing complete verbatim inputs.

- Pass the marker—again having prepared the online template or easel title/banner, have participants contribute in the order of an assigned round-robin sequence to list their ideas.7 When in person, passing the marker after lunch or when participants’ energy ebbs helps get participants up and moving around. Help them with their penmanship if necessary by telling them to write larger and encourage the use of more white space.

- Pass a sheet or post a digital template—particularly appropriate if time is short, the group is large, or you have many questions requiring input (distribute a separate sheet for each question). Write the question or title on individual large cards or pieces of card stock, and either sitting or standing, have the participants pass them around until each person has had the opportunity to contribute to each question. This activity helps reduce redundant answers, since participants can see what prior people have written.

- Post-it notes—Have individuals write one idea per note, as many notes as they want, and mount them on the appropriate easel, whiteboard, Mural, or Miro.8

- Round-robin—having prepared an online template or in-person easel title or banner, and in consort with a scribe or scribes, create an assigned order in which the participants offer ideas, one at a time, permitting anyone to say “pass” at any time. Consider one last round-robin for any missed or final contributions, again allowing participants to say “pass” if they have nothing to add.

NOTE: Consider time-boxing your ideation activity if necessary, typically in the range of 5–10 minutes. However, if you fastidiously enforce the “high-energy” rule, you will discover that most groups cannot maintain high energy around a single question for more than 6–8 minutes.

2. ANALYZING ACTIVITY

Consensual understanding provides the foundation for all analysis. Analyzing comprises 80 percent of the Brainstorming effort. Listing is quick, as we just saw. Therefore, first “scrub” the lists and validate the clarity. Challenge participants as to why they contributed an item. Scrubbing may be quick or demand analyzing each item to determine

- what it means—define it (Defining Tool);

- whether it should be combined with another item or items (Categorizing Tool);

- the merits of each item (Prioritizing Tool); and

- whether it should be deleted as inappropriate, redundant, or superfluous.

To analyze successfully, you must first know what you are building. Know in advance what you are going to do with the list—what questions to ask and how you are going to clean up and document the final list.

Thorough analysis frequently requires input from more than one Listing activity. For example, Deciding and Alignment require purpose, options, and criteria. Assigning requires who and what. Situation Analysis requires understanding the resources that we control and factors we don’t control.

Rely on the Analyzing activity (and all other Tools) to do the work for you. Rely on and trust the procedure, not your content knowledge. Participants may never arrive at your answer, but they will create a solution they can all understand and will support.

3. DECIDING ACTIVITY (ALSO KNOWN AS “DOCUMENT” OR “CONVERGE”)

Thorough and complete analysis frequently relies on building some type of matrix. The Analysis activity sets up the matrix. The Deciding or converging activities document consensual findings resulting from the analysis your group set up by completing the matrix.

While I always remain hesitant about letting any tool make our decision for us, tools will frequently enhance focus by getting a group to agree on what not to consider or what not to talk about anymore. Tools help groups deselect. After deselection, most decisions are win-win because the remaining options may all be robust enough to secure everyone’s support. We have rid ourselves of the weak options and the noise they generate that causes distractions in meetings.

At this point, your definition of consensus becomes critical. We may not be able to find a solution that is everyone’s favorite. In fact, we usually won’t. We may even develop a solution that is not anyone’s favorite. But we have facilitated consensus by building an agreement, decision, or solution that everyone will support while not causing anyone to lose any sleep or withdraw their support.

Therefore, on a separate screen or sheet of paper, document the final list, output, or choice depending on what type of deliverable you have built. Confirm buy-in with your participants, securing an audible response from each participant as an outward sign of agreement and support. In highly contentious and politically charged situations, I’ve even circulated an 8.5-by-11-inch or A4-sized sheet of paper and required each participant to sign or initial.

COMMON PITFALLS TO AVOID

Plan Brainstorming ahead of time. Write down your precise question or questions before starting. Have a clear understanding of what you are building (a list of options, criteria, or whatever it is) before you start. Other cautions to heed include avoiding these pitfalls:

- Asking a question that is too broad or vague (such as “How do you solve global hunger?,” “How do you boil the ocean?” = “What should we do about it?”); always remember that Y = (f) X’s, so ask about the X’s and do not ask directly for the Y

- Asking the group “How should we categorize the list?”; if you do not know how, then prepare more thoroughly—groups frequently over-categorize and make things too general when they should head in the opposite direction and more fully articulate the attributes, characteristics, and specificity that describe their items

- Being the first to start a conversation by not waiting until everyone’s input has been gathered and confirmed

- Cadence—not knowing when to stop or stopping too soon

- Not enforcing that everyone, including the meeting facilitator, must avoid any conversation while listing

- Not having an activity or tool prepared to analyze the list

- Not writing soon enough, waiting for speakers to finish, and then asking them to repeat themselves (to avoid this pitfall, write while they are speaking—it is easier to correct something wrong than to go back and remember something that was “right”)

Breakout Teams Tool

Using Breakout Teams captures more information in less time and helps you overcome the monotony of relying too much on group Listings. Consider Breakout Teams whenever you are gathering information and ideas, typically where more is better.

NOTE: When building consensus, it is frequently best, however, to defer your Analysis activity until all teams have returned and assembled as one integrated group.

PROCEDURE

- In advance, have Breakout Teams assigned, predetermined, and provide reasons for how you determined who is assigned to which group.

- Provide something more creative and appropriate than relying on seating arrangements (such as “this half of the room”). Consider quick yet creative methods, such as alphabetically sorting participants’ names, birthplaces, birthdates, clothing colors, favorite ice cream flavors, and so on. You might even use a deck of playing cards, and everyone drawing the same suit forms a team.

- Appoint a CEO for each team, telling them after the appointments have been made that CEO stands for the chief easel operator (with laughter as a response).9 Assign their workspace (northwest corner of the room, or Room 3, for example), and have their workspace set up and provisioned with supplies such as an easel, paper, and markers. The CEO is not responsible for scribing but does provide a single point of contact when you ask that team for a status update. Ignore the loudest person or the person who speaks first, enforcing the status of the CEO role.

- Visibly post your assignment and questions to be addressed on a screen or handout. Be clear and explicit with instructions and the format you expect each team to follow (such as listing or illustrating). Keep the questions or instructions posted and available. Print and distribute copies for each CEO if teams gather outside the main meeting room.

- Remind team scribes to capture verbatim inputs and to use black or dark blue markers that are easier to read when they present their findings to the other teams. Also tell team scribes to contribute their own ideas toward the conclusion only if those ideas have not already been mentioned.

- When capturing content online, remind team scribes to shrug off any criticism about spelling. I show the symbol ☑ and tell them that this is a spell-check button for large easel paper and online note-capturing tools that will fix all the errors when the meeting has completed.

- Give teams a precise amount of time or a deadline and monitor them closely for functionality, progress, and questions that arise. You will be shocked how much teams can get done in three minutes with clear instructions.

NOTE: Be creative. Other ways to assign teams include birth order position, latitude of birthplace, mountain peaks, rivers, constellations, land features, mythical gods, historical icons, hobby or game themes (for example, sports), places, emotional categories, entertainment icons, and hobbies. If you want them to be creative, then walk the talk. For larger groups, consider using the day of the week you were born (making sure it can be looked up if they don’t know), name of their first pet, first concert they attended, and so on.

Coat of Arms Tool

Any time you seek answers to more than one question, Coat of Arms can be used during the Listing activity of Brainstorming. Use Coat of Arms whenever you have multiple questions. The Coat of Arms is especially helpful when developing input for brief Mission or Vision expressions for any group or business. Always use in conjunction with Breakout Teams, thus creating more than one Coat of Arms.

PROCEDURE

Provide participants or teams with written and posted questions along with pre-drawn templates for their Coats of Arms. Partition each Coat of Arms into the same quantity of sections as you have questions. Typically carve out three to seven sections with a discrete corresponding question for each section.

- Use with Breakout Teams described on the previous page.

- Allow each team 3–10 minutes to draw answers to the questions, using illustrations in their respective sections, without using any words on their illustrations.

- Monitor teams closely and be flexible enough to extend the amount of time if required. When completed (if in person), have them mount their drawings in the front or center of the room.

- After the teams reassemble as one group, write down the interpretations by each CEO-appointed spokesperson (CEOs can always delegate). Do not wait until they are done speaking, forcing them to repeat as you write down their explanations; begin writing as they speak.

- Never cross out or write on their drawings, and do not interpret the drawings yourself. Always shift as much airtime as possible to your participants.

- Once the teams have completed their interpretations, ask for volunteers to integrate the list of sentiments that you wrote down into final expressions that everyone can support.

HELPFUL HINTS

- Maintain cadence. At quick intervals, prod the group to see whether the core concepts have been written down. If so, summarize and move on.

- After converting the drawings to narrative, reread entire expressions from the very beginning to see whether there are any modifications. Groups need to hear full expressions in final form.

3. Values (Who Are We?)

Values define the principles or internal rules, laws, policies, and philosophies of their conduct—the “stuff” we carry with us and value. To me they answer simply, “Who are we?” Weave your analogy into your introductory remarks.

You will also see Values labeled with different terms by organizations, such as “credo,” “professional code,” and “tenets of operation.” Completed Values may be displayed as lists, paragraphs, sentences, and so on.

DEFINED: Values describe who we are by defining “how we will work together” for the business, in support of our Mission. Some consider Values as ideals that lend significance to our lives, that are reflected through the priorities we choose, and that we act on consistently and repeatedly.10

Values may support:

- How participants manage the organization

- How participants treat one another

- Importance of upholding participants’ ethics

- Product and product quality

- Relationship to stakeholders, employees, and community

- Responsibility toward the environment

- The things to which we stay true

- What distinguishes us from others

DELIVERABLE

Values may be narrative descriptions of policies or philosophies. They may be full-sentence descriptions or phrases. Keep in mind that groups can identify both descriptive values (we are this way and walk the talk) and prescriptive values (hopes and aspirations). The former is associated with traditional management, while the latter is more associated with servant leadership.

NOTE: Ken Blanchard asserts that an organization should limit itself to three values. Employees will not remember more than three. And if employees cannot remember their Values, then why build them?11

Values define “who we are” or “the things to which we stay true.” Values provide foundation for all Agenda Steps. Eventually, we will review and validate output from the remaining Agenda Steps as harmonizing and supporting the Mission and Values, sometimes referred to collectively as the Guiding Principles.

PROCEDURE

- Define Values using the definitions given earlier or your own derivative.

- Use Breakout Teams and any Brainstorming Listing activity such as Coat of Arms, Creativity (chapter 8), or a straightforward narrative listing.

- After teams reassemble, use the logic of Bookend Rhetoric (chapter 7) to first document items that are identical or similar across teams—instant consensus. Next rotate to the most unique, and so on.

- Roll up the list by looking for common purpose as explained in the Categorizing Tool that follows on the next page.

- When the group seems to have exhausted their most important ideas, review the final Values.

Values do not have to be short statements, but what is easier to remember? Values may be full sentences (as the examples below), but they should always capture an articulate sense of “how we will work together.”

NOTE: Values are best remembered as bullet points or brief sentences. When combined as paragraph expressions, they are much more difficult to remember.

ILLUSTRATIVE ORGANIZATIONAL VALUES USING THRIVE LLC

- We don’t say “no”—we say, “How?”

- We foster risk-taking without reprisal.

- We strive to balance family life with professional responsibilities.

- We understand the importance of CREAM—Cash Rules Everything Around Me.

COMMERCIAL EXAMPLES

- “The Ritz-Carlton experience enlivens the senses, instills well-being, and fulfills even the unexpressed wishes and needs of our guests.”

- “No compromise over guest accommodation which excites the senses. No replacement of intuitive, emotionally attuned service which cherishes each and every guest.”—Regent Ball

- Donald Miller’s Storybrand organization:

- – “Be the guide (help the customer win),

- – Be ambitious (go for it),

- – Be positive.”

CLOSURE

At this point, when you have documented Values with the group’s assent, apply your analogy and move the agenda indicator for a smooth transition to Vision—an explanation about where we are headed.

Categorizing Tool

Categorizing creates clusters or chunks of related items so that groups can sharpen their focus. Similar terms describing the same logic include “affinity,” “chunking,” “clustering,” “distilling,” “grouping,” and so on. To roll up or distill any list or group of Mural or Miro items, Post-its, or other forms of multiple items, Categorizing provides both detailed procedure and the logic behind the rationale for categorizing most things: common purpose.

Categorizing eliminates redundancies by collapsing related items into chunks (scientific term). Labels or triggers that represent the titles for your chunks can be easily reused in flow diagrams, matrices, or other visual displays, making it easier for groups to analyze complex relationships.

NOTE: Never ask the group how to categorize. They don’t know how. That is why they engaged you. Explain the tool and teach them the logic of common purpose when it becomes necessary to group items.

PROCEDURE

Categorizing can take little or much time, depending on how much precision is required, how much time is available, and relative importance. After ideas have been gathered, preferably using Breakout Teams, do the following:

Underscore

Take the lists created during your ideation activity and underscore the common nouns (typically the object in a sentence that is preceded by a predicate or a verb). Use a distinct color marker or shape12 for each group of nouns, and have the team add any synonyms or similar expressions that capture the intent for each group of items underscored.

Transpose

Ask a volunteer to take one grouping of underscored items (at a time) and provide a term or phrase (category) that combines, integrates, and reflects the sentiment of all the items underscored in that specific color (or shape).

Write the new term or phrase (category) on a separate page or screen. Use the Definition Tool to reinforce clarity if participants require better understanding.

Scrub for Clarity

Return to the original list—ask, confirm, and then delete items that now collapse into the new expression that you rewrote during the Transpose activity above.

The Don’t Forget Question

After each new category, before moving on, don’t forget to ask, “Which other items not underscored also belong to this category?” If so, delete those items or parts of them as well.

Remaining Orphans

Allow your group to focus on remaining items that have not been eliminated and decide whether they require unique expressions, need further explanation, or can be deleted.

For each item not underscored or remaining, consider asking “Why ?” Items that share common purpose may be categorized together. Create a new category if they remain unique or delete them if they are inconsequential.

Everyone witnesses building the final list, which now belongs to everyone, rather than being associated with one team or another. The original team contributions should be discarded once the group confirms that the sentiment has been effectively captured with the newly written term or phrase.

NOTE: Always cross out and rewrite listed items so that there is one final list when you are complete. Everyone should witness the rewrite and now become an owner. Ideas should not belong to the contributor, and if you keep the original version, it will always belong to the person or team who wrote it.

Review

Before transitioning, review the new expressions (categories) and confirm that team members understand and will support them. Let team members know that they can add to the categories later, but if they are comfortable as is, move on, since the new categories may be reused later.

You are helping your group move raw input into a refined output on a new sheet or screen. Deleting their raw input when rewritten makes it easier to focus on the items not yet deleted. When the new categories are documented, with everyone present, it also transfers ownership because everyone witnesses and participates in creating the new categories (expressions).

LOCK INTO THE LOGIC OF CATEGORIZATION

The primary reason for categories of things is common purpose. Look at how we organize in businesses. Walk around an office building and you will see that people are grouped together, organized around “things.” They are not organized around verbs.

Treasury personnel are organized around financial assets. Human resources are organized around human capital. Sales and marketing are organized around customers. Everybody performs the same verbs. They all plan, acquire resources, do their work, and control for the work they’ve done. What gives rise to the separation or categorization is symptomatic of the nouns or resources but the driving force behind the categories of most things is simply common purpose. Engineering has common purpose around products. The Enterprise Project / Program Management Office (EPMO) has common purpose around projects—and so on.

If there are arguments or uncertainty about which category something belongs, simply challenge the group with “Which purpose does it best support?”

LESS COMMON CATEGORIZING PATTERNS

People visually perceive items, not in isolation, but as part of a larger whole. These principles include human tendencies toward common purpose. Other, less common reasons for the “categories of things” may include these:

- Continuity—an identifiable pattern

- Proximity—physical closeness to one another

- Sizing—using a common unit of measurement

- Timing—based on duration, time of occurrence, or sometimes frequency

4. Vision (Where Are We Going? How Do We Know If We Got There or Not?)

It is hard enough to get a family of four to agree on where to go out to eat, much less getting a group of directors, executives, and managers to agree on where they want to drive their organization.

Vision defines the direction of an organization by providing details about where the organization wants to go. Vision should appeal to both the head and the heart, supporting the question, “Why change?” A clear expression of the future helps to gain genuine commitment. Illustrate your definition with your analogy.

A Vision is a desired position specified in sufficient detail so that an organization knows when they reach the Vision. A consensual Vision provides direction and motivation for change. Optimally, a Vision should be specific enough to differentiate your organization from competitors.

DELIVERABLE

A few clearly defined expressions or a brief paragraph 25–75 words in length. Consider beginning with “We aspire . . .”

RELATIONSHIPS

Vision anchors the forthcoming Measures Agenda Step by expressing where your organization is headed. When thoroughly constructed, Visions:

- Provide a picture of what the organization aspires to become

- Motivate and energize members to focus on priorities

- Enable individuals and teams to make trade-offs or eliminate options for consideration

- Sanction Measures whereby individual and organizational performance can be evaluated

BASIC PROCEDURES

- Use Breakout Teams (chapter 6).13

- Use Temporal Shift Tool (chapter 6).

- Apply Categorizing (chapter 6) to distill their various aspirations into a common Vision expression they all support.

RIFFS AND VARIATIONS

Asking “Where have you been?” is too broad to effectively stimulate. Consider the dozens of Perspectives (chapter 8) to provide additional input that aggregates into a broader, overreaching Vision, a view that considers the evidence and facts arising from answers to questions such as these:

- Where are the thrust and focus for future business development and growth? Which products and services? Which customers?

- What channels, markets, products, and services should be minimized or excluded in a future vision?

- What core competencies are sought to take us into “tomorrow”?

- What does our business look like “tomorrow” if we do not change?

- What product or service mix or decision criteria will change over time, enabling us to get ahead of customer and market expectations?

- Which financial parameters drive the likelihood for growth and returns on investments?

The following is an example for the organizational Vision at THRIVE LLC:

We aspire that contractors, developers, and homeowners will order THRIVE products and services before their new home construction or renovation begins. Residential families will begin to THRIVE before they take occupancy of their property. They will view us as a trustworthy partner as they begin their new life, in a place they may consider foreign, but we will help them occupy as familiar so that they THRIVE and feel like home.

CLOSURE

This Agenda Step concludes when you have an expression or paragraph that the group believes captures the target or Vision of where they want to go. Confirm enough detail that they can recognize the target, and would all agree when they get there. Use your analogy and move the agenda indicator for a smooth transition to Key Measures, setting goals and objectives (milestones) along the path toward reaching the Vision.

Temporal Shift Tool

Temporal Shift helps groups agree on where to go or be at some point in the future. It is much easier to ask and build consensus around “Where have you been?” or “What type of legacy have you left behind?” than to ask, “Where would you like to go?”

PROCEDURE

Temporal Shift defines a specific forward-looking view (Vision) of a group or organization in sufficient detail so that a group or organization can easily agree when they reach it (or not). Subsequent planning efforts direct attention toward reaching the Vision. Looking forward, shaping curves, or Vision help determine the optimal goals, objectives, and measures.

- Use Breakout Teams (chapter 6). Put each team and all the participants on a warm island with a beautiful beach and a cool breeze.

- Have a newspaper or industry magazine preselected for your participants to read.

- Hand out recent copies of an appropriate industry or trade magazine or periodical familiar to the participants. Decide which part of the paper or magazine will display a headline based on the success of the group (could be a column or specific section).

- Remind everyone that they are on the island at some point in the future. Calculate the point in the future as a date by when this team will have disbanded. For a project team, only 2–3 years. For executives, 5–25 years. Some Asian organizations look ahead 50 years; but it’s frankly tough to get most North American organizations to look past 5 years.

- Have participants turn to a specific page (could also be the front cover or front page) or column that is frequently read. The Wall Street Journal serves as a default publication.

- Have each Breakout Team first develop a newspaper headline that they would like to see when reading this paper while sitting on that beach in the future—for example, “What would the headline read on January 15, 20__?”

- After they complete their headlines, instruct them to draft the story behind the headline, in the form of a 250-word article. Their headlines and stories become the foundation for integrating their final Vision expression.

- Bring the teams together to compare and analyze. Use the Bookend Rhetoric (chapter 7) to look for substantive similarities and differences. Rely on common purpose (Categorizing, chapter 6) to distill their input into final expressions or statements.

- Remember, first create the headline. The story augments the headline with details. Consider a final written expression starting with “We aspire . . .”

- Surprisingly, the article takes them less time to write than the headline, as the article becomes the “meeting minutes” of the conversation and “arguments” leading into the headline.

NOTE: When you have them pretend they are on a beautiful beach sometime in the future and pick up a periodical displaying a headline about their efforts, what you are really asking them is “What is the legacy you have left behind as a result of the effort you began back in this meeting?” See the following website for today’s headlines worldwide, which could also be printed and given to team members, thus providing tactile stimulation: https://www.freedomforum.org/todaysfrontpages/.

5. Key Measures Agenda Step and Tool (What Are the CTQs, KPIs, and OKRs?)

This Agenda Step defines what the organization will Measure to determine its progress reaching its Vision. Relate each of the three measurement types explained here back to your analogy.

KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS OR CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS

The deliverable from this Agenda Step may be called by many names:

- Considerations

- Criteria

- CSF (Critical Success Factors)

- CTQ (Critical to Quality)14

- FMA (Future Measurement Acronyms)

- Goals

- Key Results (“OKR” stands for Objectives and Key Results)

- KPI (Key Performance Indicators)

- Leading indicators

- NCT (New Consulting Terms)

- Objectives

There are three general types of criteria: (1) SMART (specific, measurable, adjustable, relevant, time-based), (2) fuzzy, and (3) binary. In the most common vernacular, these three types correspond with objectives, goals, and considerations. An objective “measure” is a standard unit used to express the size, amount, or degree of something.

An objective is a desired position reached by Actions within a specified time. Objectives provide measurable performance indication ![]() and are commonly made SMART.15 With shorter duration than goals, they may be viewed as milestones en route to reaching goals.

and are commonly made SMART.15 With shorter duration than goals, they may be viewed as milestones en route to reaching goals.

A goal is a directional expression that may remain fuzzy or subjective to each observer ![]() . Although a goal may not be technically SMART, it is directional and on a long-term basis, a deep-reaching, fuzzy criterion, or a measurement that might decompose into multiple objectives (or key results).

. Although a goal may not be technically SMART, it is directional and on a long-term basis, a deep-reaching, fuzzy criterion, or a measurement that might decompose into multiple objectives (or key results).

A consideration is a binary (yes or no) management issue, constraint, or concern that will affect reaching the Vision ![]() .

.

DELIVERABLE

Clearly defined Measures or success criteria including a range of objectives, goals, and other considerations.

RELATIONSHIPS

Key Measures enable using measurements to calculate progress and the distance from reaching the Vision. Measures provide milestones that enable your group to better shape and define the most appropriate strategies, activities, or tactics (what to do to reach the vision).

BASIC PROCEDURES

Use the ideation activity of Brainstorming to draft and specify candidate Key Measures. See the Scorecard Tool (chapter 7) for additional detailed analytical support and scripting when analyzing Measures.

- First obtain rough ideas using the rules of ideation found in Brainstorming.

- Then explain the three measurement types (Objectives [SMART], Goals [fuzzy], and Considerations [binary]).

- Use the logic and rhetoric of the Scorecard Tool (chapter 7) to analyze the input and convert ideas into final and calculable Measures.

- To ensure clarity and consensual understanding, be prepared to use the Definition Tool (chapter 6).

- Review the fully defined Measures and assign Measures to a category by coding them as shown: Objectives

, Goals

, Goals  , or Considerations

, or Considerations  .

. - Analyze each objective

, one at a time, and make them SMART. Do not show the SMART definition until after you have completed writing down the initial input during Listing. Use Breakout Teams (chapter 6) to convert draft Measures into final form, making sure they are SMART:

, one at a time, and make them SMART. Do not show the SMART definition until after you have completed writing down the initial input during Listing. Use Breakout Teams (chapter 6) to convert draft Measures into final form, making sure they are SMART:

- – Specific

- – Measurable

- – Adjustable (and challenging)

- – Relevant (and achievable)

- – Time-based

- Remember to challenge SMART objectives by first identifying the unit of measurement. The unit of Measure is what we need first, not how we measure it (more on this later).

- Eventually, detail the precise calculation or formula and stipulate the source for obtaining the data to be used (including report name and line item from a spreadsheet if applicable).

- Separately list and fully define the remaining subjective goals (fuzzy and not SMART) and other important considerations (if any).

CAUTION: When purchasing a new vehicle, you may seek ample leg-room in the back seat. What is the unit of measurement for ample leg-room? If someone says “inches,” are we talking about linear inches, square inches, cubic inches, or a tesseract?

If linear inches, measured from what point to what point? For this exercise we need to know “linear inches measured from rear middle of the parallel seat in row one when fully upright to the front of seat where the knees bend in the second row” (or whatever we are told the measurement is). We do not need to know how it is measured, whether using a tape measure or a laser scope.

Be careful in your organization to document the source of the data. For example, if the unit of measure is “barrels of oil,” where are we obtaining the data? Which report? Which line item? We do not want participants to argue later over dissimilar sources of data.

The following discussion uses both THRIVE LLC and mountaineering as examples. Draw upon your own analogy for illustrative support.

THRIVE LLC objectives (SMART):

- Produce a detailed month-end analysis of sales from distribution channels within two hours, compared with 72 hours with the existing technique, using Report ABCD and line item 34 and have the sales total accessible for use by EOD (end of day) April 15, 20__.

- Accelerate organic growth beyond industry average of 7 percent per year, targeting 10 percent cumulative annual growth rate, by end of year, December 31, 20__, using Report ABCD and line item 73.

THRIVE LLC goals (fuzzy):

- Build leadership in the industry and become a go-to organization when others are seeking advice.

- Be feared by our competitors and other competitive options.

- Concurrent development and commitment of business units, including the determination and balance of dashboard success measures.

THRIVE LLC considerations (binary):

- Given current macroeconomic conditions that drive the new housing market, retire US$50 million in existing long-term debt by July 1, 20__.

- If Competitor X launches a new product line in widgets, leverage our analysis of other widget manufacturers to explore mergers or acquisitions.

ICONIC SUPPORT (MOUNTAINEERING ANALOGY)

Provide a legend that explains the icons you will use to code their input (using mountaineering to illustrate). You will also need a legend or artifact that defines SMART:

- Objectives

: Be at 5,000 meters by 17:00 hours UTC Friday, April 15, 20__.

: Be at 5,000 meters by 17:00 hours UTC Friday, April 15, 20__. - Goals

: Take some nice photos when we reach the summit.

: Take some nice photos when we reach the summit. - Binary considerations

: Did we reach the summit, or not?

: Did we reach the summit, or not?

Keep a Key Measures legend visible and easily accessible until you complete the Actions (such as strategies, projects, and activities) and Alignment activities later. The team will need to refer to Key Measures to justify proposed Actions and to clarify, add, or delete Actions.

Script your analogy by relating your analog to the three types of Key Measures. What measurements indicate progress toward reaching the Vision? Measures are appealed to continuously when analyzing the Current Situation to determine the most optimal Actions.

CLOSURE

When the SMART measures have been fully built, and the non-SMART measures have been defined, close this Agenda Step. Move the agenda indicator to the next Agenda Step, Current Situation (also known as Situation Analysis). Emphasize that Key Measures are created to provide indication of progress toward reaching the Vision.

Definition Tool

Keep this Definition Tool in your hip pocket and be prepared to use it whenever you encounter discord over the meaning of something. You may also need this Tool when you manage open issues (Parking Lot, chapter 5) and during your Review and Wrap if your participants do not agree or cannot remember what something meant.

WHY?

Facilitators need a robust and objective Tool for defining terms, phrases, and other “things” mentioned by subject(ive) matter experts. The standards listed are demanding and include five separate activities.

I created this unique Tool to quickly build consensual agreement around words, terms, and phrases. However, for concepts like processes, a more extensive and illustrative Meeting Approach like Activity Flows (Process Decomposition)16 might be required.

PROCEDURE

When a term or phrase requires further definition or understanding, never rely exclusively on dictionary definitions.17 Instead, facilitate the group’s definition with the following five questions or activities:

- First identify what the term or phrase is not. For example, as a highly appreciative gift idea, a camera is not something disposable or pre-used.

- Compile a narrative sentence or paragraph that describes it. For example, the camera is a handheld device for recording photographic images. If you must use a dictionary or other professional definition, use it to compare with something the group has already built to identify something important that is missing.

- List the detailed bullets that capture specific attributes, characteristics, or specifications of the term or phrase as intended by the participants. For example, with a camera, we might detail requirements for the quantity of mega pixels, digital zoom range, and so on.

- Get or secure a picture of concrete items or create an illustration of the item if it is abstract or dynamic (such as a process flow diagram).

- Provide at least two actual, real-life examples from the participants’ experience that brings the term or phrase to life. For example, a gift camera might be a Canon EOS Rebel T7 or a Nikon D3500.

6. Quantitative TO-WS Analysis Agenda Step (What Is Our Current Situation?)

Quantitative TO-WS (Threats, Opportunities, Weaknesses, and Strengths) Analysis reviews the Current Situation and is more frequently referred to as SWOT Analysis. While rare in use, I find TO-WS more appropriate, for these reasons:

- Evidence indicates the best sequence for Situation Analysis begins with the external and uncontrollable threats and opportunities before moving to internal and controllable weaknesses and strengths.

- I will introduce you to a quantitative Tool that I built to help groups generate consensus when prioritizing hundreds of options. Being unique, TO-WS brings a fresh sense to invigorate a stale tool (SWOT) that is poorly facilitated in most organizations.

- SWOT has left a bad taste in people’s mouths because they create four lists, hang them on a wall, stand back, and ask: “What should we do differently?” While some answers pop out of “flatland,” rarely can you drive consensual answers with an unstructured style that uses a “global hunger” question like “What should we do differently?”

I developed my Quantitative TO-WS Analysis in 1994 while attending Northwestern’s Kellogg Graduate School of Management because, unlike the four-list style, Quantitative TO-WS Analysis . . .

- develops shared understanding,

- making it easier to build consensual Actions,

- that ensure achieving or exceeding the Key Measures,

- established to reach the Vision.

As this Agenda Step develops you will see how easy it should be to apply your personal analogy.

NOTE: Time and time again, my students with MBAs and PhDs have commented that for them, two “lightbulbs” turned on with my structured planning that had never been clear in school:

- The difference between Mission and Vision and why people are so often confused (chapter 6)

- How to effectively use the logic and precise rhetoric of TO-WS to help build consensus

DELIVERABLE

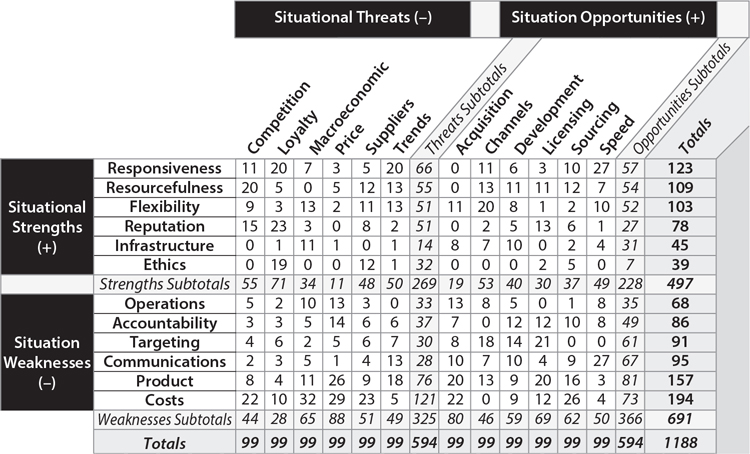

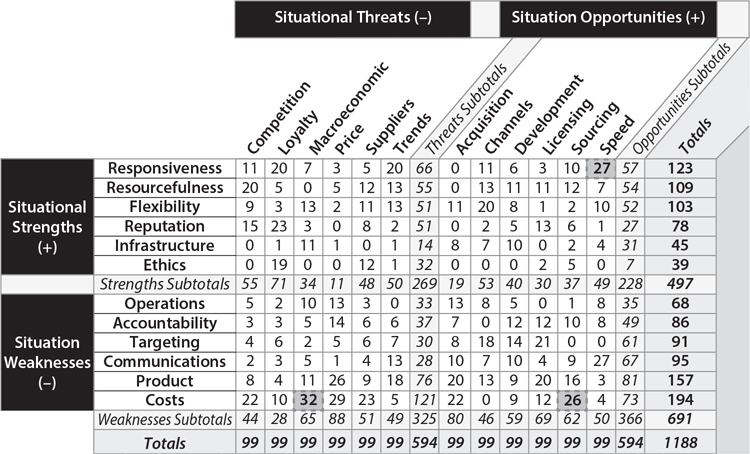

A numerical analysis that describes the Current Situation, Quantitative TO-WS makes it possible to prioritize hundreds of options (Actions). TO-WS Analysis helps groups visualize their current situation and prioritize hundreds of potential Actions on a single page or screen.

NOTE: Previously we have relied on words (narrative), icons (symbols), and drawings (illustrations). Because we confront hundreds of potential strategies, initiatives, products, or projects, the numeric Tool that I use here makes it easy to deselect weak options and focus energies on the best options.

Quantitative TO-WS Analysis Tool: Current Situation or Situation Analysis

This Tool describes the Current Situation by developing shared understanding that supports what Actions a group should embrace so that they reach their Key Measures (chapter 6), such as objectives (SMART), goals (fuzzy), and considerations (binary).

A quantitative view of the Current Situation displays the foundation for justifying Actions. Actions that currently work well are potentially reinforced and renewed alongside new Actions that get approved and developed.

The term used to describe Actions will change depending on your level in the holarchy. For example, an organization will refer to Actions as strategies, a business unit may call them initiatives, a department or program office may call their Actions new products or new projects, and a product or project team may call them activities or tasks. For each group respectively, the term used represents what the group is going to do to reach its Key Measures that were established to ensure that the group achieves its Vision (chapter 6).

The Current Situation provides consensual descriptions of the following:

- Current environment (TO-WS)

- – Threats (externally uncontrollable, frequently trends)

- – Opportunities (externally uncontrollable, frequently trends)

- – Weaknesses (internally controlled, as viewed by competitors or competitive forces)

- – Strengths (internally controlled, as viewed by competitors or competitive forces)

- Assumptions made in developing analysis

- Model representing how stakeholders view the business or organization

- Input for determining what Actions the group foresees, given their Current Situation, to help reach or exceed their Measures in support of achieving their Vision

GENERAL QUESTIONS

- Which threats are most worrisome and justify defense?

- Which opportunities provide a real chance of success?

- Which weaknesses need the most correction?

- Which core competencies or strengths should be leveraged?

ALTERNATIVES

This Agenda Step may be completed one of two ways:

- Traditionally, Situation Analysis may be mandated for a department, project, or work area and completed in advance. Once that effort has been explained and clarified, summarize, and move on to the next Agenda Step, developing Actions to reach the Key Measures.

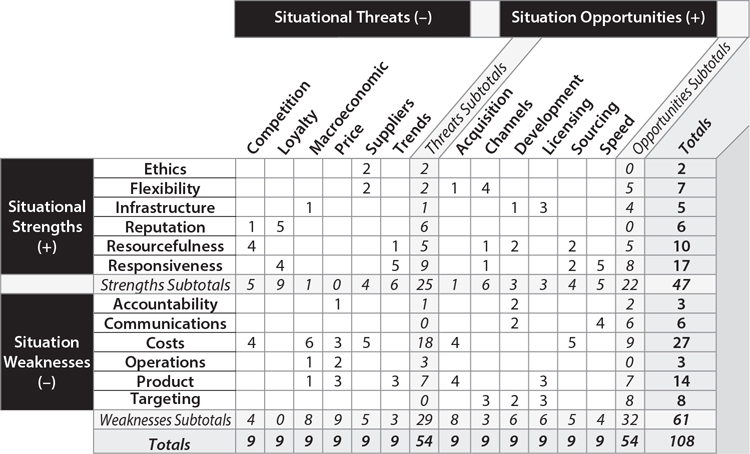

- Alternatively, use my proprietary Quantitative TO-WS Analysis (figure 6.2). Separate the external things we have no control over (threats and opportunities) and the internal things we control (weaknesses and strengths). Then use my numerical Tool for analysis that helps develop group comprehension and understanding about what Actions will have the greatest impact, given the group’s Current Situation, to reach the Key Measures (akin to identifying what we should do different tomorrow).

Figure 6.2. Blank TO-WS Worksheet

PROCEDURE

I call this analysis TO-WS because most experts agree this is the best sequence to consider:

- External Threats: It’s easy to imagine what could go wrong.

- External Opportunities: Since threats come easier, remind participants to refer to their personal list of prepared factors.

- Internal Weaknesses: Participants are usually more sensitive about things going wrong than with what is positive.

- Internal Strengths: Begin by referring to participants’ personal notes.

To conduct this analysis, do the following:

- Have participants prepared to share their TO-WS factors in advance but keep them private. Let participants reference their personal notes as we proceed.

- Develop consensual lists and complete definitions (Definition Tool, chapter 6) for each threat, opportunity, weakness, and strength. If necessary, reduce each list to the top four to six factors; see Categorizing logic (chapter 6) and then use PowerBalls (chapter 7) for prioritizing, along with Bookend Rhetoric (chapter 7) to prevent wasting time.

- – As you build four different lists, describe each entry clearly and carefully. Threats and opportunities are externally uncontrolled and frequently represent trends. Weaknesses and strengths are internally controlled as viewed by competitors and outsiders.

- – Build and enforce strong definitions and potential measurements behind each TO-WS item. For example, strength of “brand” could be measured as market share among target customers, or the threat of “transportation costs” could be indexed to the cost of a barrel of oil or price for a liter of diesel.

NOTE: While the four-list style for Situation Analysis is normally called SWOT, technically, there are only two lists, both with a positive and a negative end of their continuum. If the factor is external and you do not control it, by definition it must be a threat or an opportunity (TO). If the factor is internal and you control it, by definition it must be a weakness or a strength (WS).

REMEMBER: NEVER allow a group to define an internally controllable weakness as an opportunity for improvement. If it is controllable, by definition it is a weakness and not an opportunity.

- Create a definition package so that each of the characteristics scored is based upon agreed “operational definitions.”

- Transfer your four lists into a matrix (usually a spreadsheet), with Threats (–) and Opportunities (+) on the horizontal axis and Strengths (+) and Weaknesses (–) on the vertical axis (because it is easier to visually focus with columns rather than rows).

- Remind participants that they are on the inside looking out and have them score, using instructions that follow.

- Aggregate the individual scores into a collective score. If you are using the spreadsheet, it will automatically calculate a group total.

- Review with the group to identify the most impactful Actions—strategies, initiatives, products, projects, or activities.

CRITICAL NOTE: Carefully enforce the operational level in your holarchy and meeting scope, because the strengths and weaknesses must be within control of this group, not simply the company or organization. For example, a department may not control its budget, so financial resources may be viewed as a threat to the group because they do not control the budget or financial assets.