CHAPTER 8

DIGITAL POLLUTION

The Collateral Damage to Society

Iteration-led products find local maxima by optimizing financial metrics, but in the process, they often have unintended consequences on society. The iteration-led approach is so common that we have learned to accept a dichotomy: you can be successful, or you can make the world a better place.

We see mounting evidence of a generation of disillusioned employees in the technology industry coming to terms with this dichotomy. Employees at Google and Amazon have staged walkouts to protest how their employers’ products and practices are failing society.1 Uncanny Valley, the memoir of a young professional trying to find meaningful work in the tech industry, became a New York Times bestseller. Websites like Tech for Good offer tech employees sparse hope that they can still find work that doesn’t spark an overwhelming desire to wash one’s conscience afterward.2

These examples reflect the growing dissatisfaction of the cohort that entered the tech industry inspired by the vision that technology and innovation were going to change the world. For a while, the sheer volume of products and startups launched made the change seem like progress. But recent studies show that technology hasn’t always made the world better.3

Here’s a personal example of what sounded like a promising innovation. When my son was seven, he came home from school excited about a game, Prodigy, that he had played at school. His math teacher had introduced it to the advanced math students in his class as a way to keep them engaged. It was popular among his friends too, and he was begging me to play it. It turned out that my daughter, who was 10 at the time and also an advanced math student, had also been introduced to Prodigy. She, however, didn’t share her brother’s enthusiasm for the product.

As I watched the gameplay in Prodigy, it was soon apparent why—the game lets you pick your character (reminiscent of Pokémon) and attack your opponent by answering math questions correctly. The gameplay seemed to be clearly targeted at boys. Studies have shown that the motivation behind playing video games differs by gender: while boys frequently want to compete (duels, matches) and use guns and explosives in the game, most girls’ primary motivations are completion (collectibles, completion of all missions) and immersing themselves in other worlds.4 This difference was playing out in how my kids perceived the game—even Prodigy’s marketing video in 2017 showed boys pumping fists while girls were rarely featured in the video, and in the rare seconds that they were, they didn’t show the same level of enthusiasm.5

Curious to see if my kids thought it was designed with a particular gender in mind, I asked them. “Definitely boys,” my son replied. My daughter added with biting sarcasm, “But don’t worry, the next version will be for girls and it’ll have Disney princesses that invite you to tea if you get the answer right.” My 7- and 10-year-olds could see through the gender targeting in the product.

As if to confirm their views on gender stereotypes, a 2018 video on Prodigy’s website designed to sell parents on the benefits of membership shows a young boy explaining why he loves learning math on Prodigy and that he can do all multiplication and division problems easily. “What is 9x9? It’s 81. Easy!” he exclaims. This is followed by an enthusiastic little girl’s recommendation: “I also love being a member. You could get these new hairstyles, new clothes, those hats, those shoes.” She says nothing about learning or math.6

A product could target all children equally, without gender stereotypes. Khan Academy purposefully took this approach. Its former vice president of design, May-Li Khoe, explained in our conversation:

Khan Academy’s mission is to provide a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere. That meant to me that we were working to create a more equitable world. I wanted that lens of equity to permeate all of our work, from hiring to illustration. This required additional effort.

It meant I was spending time ensuring design decisions were made to support that vision, including hiring and mentoring team members to do this. It meant my team and I put work into codifying values and designing processes to entrench the ethos of equity into all of our work, such as establishing photography usage guidelines to combat stereotypes. Often this effort isn’t reflected in typical financial metrics, but we knew it affected our brand and potentially any student and teacher who sees our work.

Khan Academy’s visual direction is designed to be gender-neutral. Even the names used in word problems were diverse, thanks to the efforts of Khan Academy’s content team. While these inclusion efforts may not have provably affected financial metrics, they certainly made a positive difference to my daughter.

In pursuit of financial metrics, Prodigy was finding a local maximum—it was effective at teaching boys math (at least my son and his friends). But the byproduct of its approach was propagating gender inequality in the classroom. By leaving out the girls in the classroom, it was missing out on the global maximum. Khan Academy was taking a vision-driven approach to find the global maximum.

In building our products, we’re constantly making choices to either find the global maximum or settle for local maxima. While online education was one example, our products touch most aspects of people’s lives including how we stay connected with friends, whom we choose to date,7 whether we get access to credit,8 whether we see a job ad,9 whether we get called for a job interview,10 and even how we may be judged by a court of law.11 In each of these cases, our products produce benefits for some while creating collateral damage.

We know how fossil fuels and other byproducts of the industrial age have affected people’s health and contributed to the climate crisis. In the digital era, a new kind of pollution, fueled by carefree growth in the tech industry, is having an unintended yet profound impact on society. This emerging trend of inflicting collateral damage through our products is what I call digital pollution. But as with any new form of pollution, recognizing it takes time. To build our businesses and develop our products more responsibly, we must be able to recognize and understand the effects of digital pollution, which can be broadly categorized into five categories.

FUELING INEQUALITY

Fueling inequality is a common form of pollution as innate biases permeate into the product, mirroring and amplifying stereotypes in society. Prodigy is an example of digital pollution that exacerbates gender inequality in STEM education.

Increasing inequality is a growing threat to society as artificial intelligence (AI) becomes more pervasive in products. Timnit Gebru, renowned researcher in ethical AI, was ousted from Google in 2020 after writing a paper that pinpointed flaws in the company’s language models that underpin its search engine. The system uses large amounts of text from online sources including Wikipedia entries, online books, and articles that often include biased and hateful language. Her research pointed out that a system trained to normalize such language would perpetuate its use.12

Gebru was arguing for more thoughtful training models for AI and the need for a more vision-driven approach to AI to prevent this form of pollution.

In addition to fueling inequality through biases in products, business practices can also increase inequality. The digital economy has increased wealth inequality to levels not seen since the Great Depression.13 For decades, through deunionization and outsourcing, the risk of economic downturns has been shifted from companies to workers. The pendulum has swung from lifetime employment with well-funded pension plans to the gig economy where workers typically don’t have health insurance. Companies hire workers as and when they are needed—any risk with an economic downturn or a decrease in demand is borne by the workers.14

Economists who believed that the weakening of labor laws would spur growth in the tech sector and, in turn, lead to better pay for workers are realizing that this may no longer be true.15 According to researchers, employment has fallen in every industry that used technology to increase productivity.16 Essentially, automation is pushing workers to lower-paying jobs in the economy.

In the same timeframe, share buybacks have reached record levels, predominantly benefiting shareholders and executives.17 Increasing inequality makes people more disillusioned with majority rule.18 Products that increase inequality are contributing to digital pollution by creating an increasingly divisive society that destabilizes society.19

HIJACKING ATTENTION

In his essay in 1997, theoretical physicist Michael Goldhaber popularized the term attention economy, where every company, influencer, and entity vies for the one finite resource: your attention.20 Each email, alert, or notification does its part in trying to hijack your attention for just an instant, keeping you in a constant state of alert, afraid of missing out. Repeated attention hijacking has two detrimental effects.

First, to maintain this hyperalert state, the human body releases the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol—several studies have illustrated the correlation between increased smartphone use and higher stress levels.21 While these mechanisms help us cope with stress in the short term, high levels of these stress hormones circulating in the body over the long term have a detrimental effect on health and mental well-being. Research shows that these high levels have an inflammatory effect on brain cells and are linked to depression.22

Second, the repeated dispersion of our attention reduces our ability to interpret and analyze the deeper meaning of information. Studies show that heavy users of the internet use shallow processing—scanning information to get a breadth of information but at a superficial level.23 If we’re not able to get to the deeper meaning of things, it’s easy to latch onto sound bites but harder to process nuance.

Society thrives on nuance. But increasingly nuance, like attention, is scarce. To understand why society needs nuance, consider the example of South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy in the early ’90s. There were extremist factions: some white supremacist leaders incited followers to take up arms to protect their privilege and property, while some Black leaders wanted payback for the atrocities of apartheid. This could have been the beginning of a descent into violence, but Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk inspired the country with a shared vision. They initiated a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to acknowledge the atrocities and to begin to make amends. Their nuanced but inspiring message resonated with the population, and South Africa made a peaceful transition to democracy.

In contrast, President George W. Bush famously said, “I don’t do nuance,” when making the case for going to war in Iraq after 9/11. Instead the argument was a set of frequently repeated sound bites that Saddam Hussein was dangerous and was acquiring nuclear weapons.

For society to function, people need the mental bandwidth and attention to be able to absorb nuance and not just sound bites. Products designed to hijack users’ attention create digital pollution by eroding our ability to absorb information.

CREATING IDEOLOGICAL POLARIZATION

Rising inequality and attention dispersion create a fertile ground for ideological polarization. While there are several underlying reasons for political polarization, including the rise of partisan cable news, changing political party composition, and racial divisions, digital products also contribute to the polarization effect.

With attention being a scarce resource, a frequently used technique to increase user engagement is to make users crave validation in the form of “follows,” “likes,” and “faves.” Studies show that this desire for validation leads people to post increasingly polarizing content and to express moral outrage.24

Algorithms too are increasingly contributing to polarization. YouTube, for example, introduced an algorithm in 2012 to recommend and autoplay videos that has worked exceedingly well and accounts for 70 percent of time spent by users on the site.25

In the process, however, YouTube has fueled conspiracy theories and radicalization online.26 Each subsequent recommendation by the platform pushes you toward a more extreme view—for example, if you start looking at videos about nutrition, after a few videos you end with recommendations on extreme dieting videos. This is now termed the rabbit-hole effect.27

Ex-employee Guillaume Chaslot, who worked on this algorithm, explains this effect of radicalization in a blog post. The algorithm creates a vicious cycle. For example, some people may click on a flat-earth video out of curiosity, but because the video was engaging, it gets recommended millions of times and gets millions of views. As it gets more views, more people watch it, and some believe that it must be true if it has gotten so many views and distrust mainstream media that doesn’t share this “important” information with them. As a result, they spend more time on YouTube and watch more conspiracy theory videos.

In effect, the smart AI algorithm increases engagement on its platform by discrediting other media. When other media channels are discredited, engagement with YouTube increases.28

Chaslot found this same recurring theme of “the media is lying” when analyzing YouTube recommendations. In the 2016 elections, YouTube was four times more likely to recommend the candidate who was most aggressively critical of the media. Similarly, the three most recommended candidates in the French election of 2017 were the ones who were most critical of the media.29

Products that increase ideological polarization create digital pollution by increasing divisions and amplifying distrust in society.

ERODING PRIVACY

As the cost of data storage has decreased exponentially over the years and the value of personal data has become evident from company valuations, it’s tempting to amass user data when building products. When there’s doubt about whether a specific type of user data is necessary, it feels smarter to err on the side of collecting this data. It might pay off later. For example, a big reason WhatsApp was so valuable to Face-book was that the firm stored data on who called whom and when, data on offline relationships that Facebook wasn’t privy to through its platform.30

Personal data helps us build better products and can help us learn more about our users and customize our offering for them. But personal data can also be used to influence individuals’ decisions, manipulate their behavior, and affect their reputation.

Most of us who build products are also consumers who are asked to make the all-too-frequent trade-off of using a free product in exchange for our personal data. Giving up personal data has become normalized to the point that we often justify giving away our data saying, “I have nothing to hide.” It’s natural to bring this consumer mindset into building products and err on the side of collecting data.

This approach, however, creates collateral damage to society. Perhaps your personal data doesn’t matter. But what if authorities can thwart change by using personal data on human rights activists or journalists to intimidate or discredit them? Erosion of privacy erodes democracy.

Privacy cannot be for the few—it’s not possible to protect the personal data of just a few individuals whose data can be used against them. Privacy is either for everyone or for no one. The few whose data really matters cannot be the only ones who advocate for privacy. Society is worse off if we don’t value privacy enough to make it standard to protect everyone’s personal data.

When we think about it this way, privacy is not just a right; it’s also a responsibility. We need a vision-driven approach to collecting and storing data to avoid digital pollution in the form of erosion of privacy.

ERODING THE INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM

The early days of the internet in the 1990s and early 2000s offered promise and hope for democratizing knowledge across the globe—anyone looking for information could have it at one’s fingertips. But in recent decades, as social media and platforms have transformed how we share and distribute information, we’re seeing how truth itself can be disrupted through disinformation.

During a cab ride recently, the conversation with my driver, Vincent, turned to politics. He shared the news that he had read about various politicians, but each time he added a disclaimer: “This is what I read, but who knows if it’s true.” His most sobering comment spoke to the erosion of our information ecosystem and the alarming spread of disinformation: “Years ago, I would open a newspaper and feel like I got the facts. Today, I have access to all the information I want, but I just don’t know what is real.”

Some of the most prominent, widely used products in the digital era have eroded our access to knowledge and facts. For example, we instinctively Google the answer to any question that might come up in a conversation. But while Google offers a powerful search tool so information is at your fingertips, its business model essentially allows the highest spender to decide the “truth.” Approximately 95 percent of web traffic from a search result goes to the listings on the first page, and few people scroll past the first page of search results. This means if you can spend enough on search engine optimization (SEO) and search result placement, you can generate content that’s perceived as the truth by the vast majority of people searching for that topic.31

Curating truth has been possible since ancient history. For example, Roman emperors commissioned mythology to be written about their divine origins to justify their birthright to rule. But creating truth required resources; the bar today is much lower.

In pointing out these issues I’m not making the Luddite argument that we were better off before the digital age. But technology and the ubiquity of information isn’t a panacea either—the spread of information too requires a vision-driven approach for the world we want to bring about. Products that contribute to eroding the information ecosystem create the paradox that with the abundance of information, gaining knowledge actually becomes harder.

The combined effects of these forms of digital pollution are starting to become evident. With the rising inequality, polarization, attention hijacking, and erosion of privacy and the information ecosystem, manipulating populations en masse becomes easier.

In 2014 Facebook demonstrated through an experiment on over one million users that it was able to make individuals feel positive or negative emotions by curating the content in their newsfeeds.32 The power of using Facebook for manipulation was known at least as early as 2010 but more fully entered public awareness after the Cambridge Analytica scandal erupted in 2018, illustrating the platform’s power in swaying elections.33

Together, these forms of pollution fray the fabric of a stable, democratic society. Most of us joined the workforce believing that our innovations could change the world for the better. Given our positive intent, it’s especially difficult to reckon with the toll our companies have taken on society.

But we must remember that we had to recognize and label environmental pollution before companies began to consider their impact on the environment and address it. Similarly, only when we recognize digital pollution can we take responsibility for the products we build.

Accepting that our products might be causing digital pollution is often difficult because the underlying product decisions are not deliberately malicious. So how do we create digital pollution when we don’t intentionally choose to?

When we’re iteration-led, we pursue local maxima by optimizing for only a few chess pieces. We miss out on the best move across the chess board, the global maximum, that accounts for user and societal well-being. In an iteration-led approach we test features in the market to see what customers respond to, and we iterate. But to assess what customers like, we look at financial metrics, typically revenues or time spent on-site. As a result, an iteration-led approach often optimizes for financial metrics without consideration for user or societal well-being.

The iteration-led approach to maximize profitability is often accompanied with the mindset that everything is ripe for disruption: “Disrupt or be disrupted!” But disrupting and “screwing up the status quo”34 without a clear purpose has often created collateral damage in society.

One example of disruption leading to a worse outcome for society is the long-term assault on the business model of news and journalism in the United States. A study of polarization in nine member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development over the past four decades found that the United States experienced the largest increase in polarization over this period. One of the major reasons was the creation of cable news, where the ad-based revenue model requires striving for high viewer ratings and has led to more polarizing content.35 In fact, the study noted that in countries where political polarization decreased in the same timeframe, public broadcasting received more public funding than it did in the United States. The disruption of the media and broadcast industry illustrates that not all that can be disrupted for the sake of profits should be.

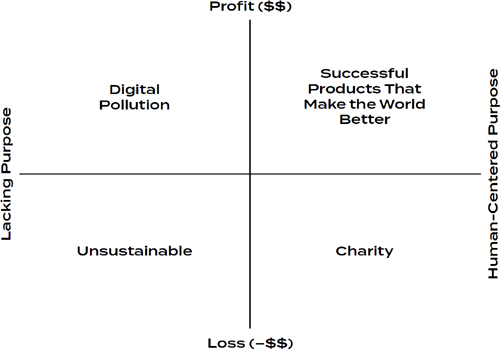

In building our products while pursuing profits, we can no longer ignore how we impact society. This is not to diminish the importance of pursuing profits. Figure 11 illustrates the intersection between profits and purpose. Companies that optimize for profits without a clear purpose create digital pollution. In contrast, organizations with a clear purpose that disregard profits are operating as charities. Charities are important but can’t carry the entire burden of creating a better world—the business world touches billions more lives than charities. For sustainable growth, society needs more businesses to pursue profits while being vision-driven.

FIGURE 11: The intersection of profitability and purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted what’s broken in our society. Iteration alone isn’t going to fix it—the future demands a vision-driven approach for every product. For example, in the United States the healthcare system is designed on the model that it offers excellent care to those who can afford it. Even before the pandemic, this model was a strain for Americans. As many as 25 percent of Americans were delaying medical care for serious illnesses because of the rising costs36—the life expectancy of the wealthiest Americans now exceeds that of the poorest by 10–15 years.37

This current business model behind healthcare also leads to a widening economic inequality. Over 137 million Americans reported financial hardship owing to medical bills, and for years, medical debt has been the primary reason for personal bankruptcies.38 Children in these families have fewer opportunities for education than those raised in families who aren’t burdened by medical debt. The unintended consequence of the current healthcare system is that it’s perpetuating wealth inequality in the United States. Having read this chapter, you now have a label for this: digital pollution.

Today’s healthcare system results from the ideology that a privatized system that relies on free markets will be efficient and good for society—it wasn’t driven by a clear vision for healthcare and the end state it creates for society. As a result, the current healthcare system has fallen victim to being iteration-led, and many companies involved have found local maxima by optimizing for profits in the short term. A vision-driven approach to healthcare could, for example, start with an inclusive vision of health as a human right. The “product” of the healthcare system would then need to be designed systematically to bring about that vision.

The 2020s have ushered in a new era that will require us to build products differently. Radical Product Thinking is a new mindset for this era so we can systematically build vision-driven products while creating the change we want to see in the world.