2

POSITIVE ENERGY IN ORGANIZATIONS

This chapter helps elaborate the concept of positive relational energy and highlights the effects of positive relational energy in leaders. It shows how positively energizing leaders affect employees and the success of their organizations. It also discusses how we can identify positive energizers and what to look for if we want to hire them in our organizations.

POSITIVE ENERGY AND LEADERSHIP

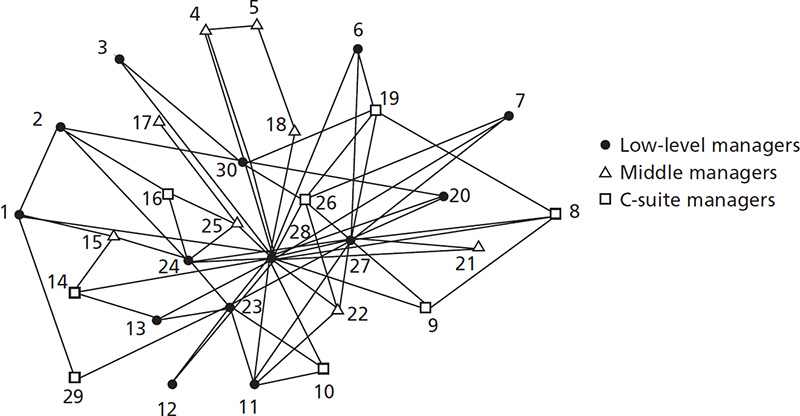

A common way to identify leadership in organizations is by examining an organizational chart. Individuals occupying boxes near the top of the chart are likely to be designated as the leaders—they are held accountable for the organization’s performance, strategy, and fiscal health. Leadership is often equated with responsibility for outcomes. Figure 2.1, for example, shows a traditional organization chart. The lines connecting the boxes show who reports to whom and who resides in the most senior positions. We have all seen these kinds of charts because they are a common way to identify who the leaders are.

FIGURE 2.1

A traditional hierarchical organization chart

Some alternatives exist for depicting the positions of people in organizations, however, and the most common is called a network map. We have all seen a network map in the back of an airline magazine. Cities are connected with airline routes, so some cities are shown at the hub and some are on the periphery in the map. In an organization network map, people rather than cities are the nodes.

So, how do we use a network map to identify leaders?

One of the most common ways to identify leaders is to construct a network map based on information flows. The relevant question is, Who gives information to whom, and who gets information from whom? The research on network analysis is very clear: if you are at the center or hub of an information network, not only are you seen as a leader but your performance is higher than the norm, as is the performance of the unit you manage.1 This makes sense. If all of the information flows through you, you can decide what to share, you know all the secrets, you control the messages, and therefore you have an advantage. Your performance will likely exceed others’ performance, and the unit you manage will surpass other units’ performance as well.

A common alternative to examining an organization’s information network is to examine its influence network. The relevant question is, Who influences whom, and who is influenced by whom? Again, the results of research are not surprising. If you are at the center or hub of an influence network, you are likely to be viewed as the leader. Moreover, your performance will be higher than the average, as will the performance of the unit you manage.2 Again, these results make sense. If you can get people to follow you, if you can influence their goals and objectives, if you can wield power over others, and if you get your way most of the time, you will have an advantage and your performance will exceed that of others.

In the academic and popular literature, influence is by far the most dominant attribute of leadership. In fact, it is almost always equated with being the leader.3 The standard assumption is that if you are influential, you are a leader. Leaders influence others. Followers follow because they are influenced by leaders.

My colleagues and I have found, however, that there is an alternative to influence as the chief indicator of effective leadership. This alternative has to do with positive energy, especially positive relational energy.4 So, how can we identify positive relational energy?

We can assess this kind of energy by asking the question, Who gives energy to whom, and who receives energy from whom? In the same way we measured information and influence networks, we can create a positive energy network map in an organization quite easily. We use the same method but ask each person to respond to the question, When I interact with this person, what happens to my energy? To what extent am I enthused, elevated, and uplifted when I interact with this person?

Note that we are not asking people to rate another person’s energy. Rather, we ask individuals to rate the energy in the relationship. A 7-point scale is used to rate one’s interactions with another person. For example, a 1 would indicate “I am very de-energized when I interact with this person,” a 4 would indicate “I am neither energized nor de-energized when I interact with this person,” and a 7 would indicate “I am very positively energized when I interact with this person.”

Having each person rate his or her energizing connection with every other person in the group produces a set of ratings associated with each person’s name. These ratings are entered into a network mapping statistical program (there are many available online), and the program creates a network map based on relational energy—that is, the energy exchanged when two people interact. We can easily determine who the positive energizers are (the nodes or hubs in the network), who the de-energizers are, and who is on the periphery and has few energizing connections. Figure 2.2 shows such a network.

FIGURE 2.2

A positive energy network

As it turns out, energy is more powerful in accounting for the performance of employees and of the organization than are influence, information, and most other motivators used to induce high performance. This evidence is summarized below.

THE IMPORTANCE OF POSITIVE RELATIONAL ENERGY

As mentioned in chapter 1, several kinds of energy can be identified—physical energy, emotional energy, and mental energy, which, over time, diminish with use. Relational energy is the only kind of energy that elevates or increases with use. Experiencing relational energy renews and uplifts us in the process of interacting with other people.

Figure 2.2 displays the positive energy network map of the managers in a large international retail firm. Each point (a dot, triangle, or square) represents a person who is rated by others on a 7-point Likert scale on the basis of the extent to which interacting with this person is positively energizing or not. The lines show who is receiving positive energy from others and who is giving positive energy to others. A rating of 6 or 7 means that a person is highly positively energizing.

The squares represent the C-suite employees or the most senior-level leaders. The triangles represent middle managers. The dots are the most junior people or those at the bottom of the hierarchy. Notice that there are several people at the senior level (squares) who energize hardly anyone (for example, numbers 8, 9, 10, and 29 in the network). They are positively energizing very few people in the organization and, one would assume, are not earning their multimillion-dollar compensation packages.

On the other hand, look at the middle of the network and you will find several junior-level people (dots) who are giving life to this organization. That is, these junior-level people are positively energizing many others and are providing an uplift to the organization (for example, numbers 27, 28, and 30); they are also receiving positive energy from many others. The point is, a person’s position in the organization’s hierarchy and the extent to which he or she is a positive energizer are not related. Whether the person is the CEO or a new analyst, a general or a corporal, a professor or a graduate student does not matter; hierarchical position is not predictive of positive energy.

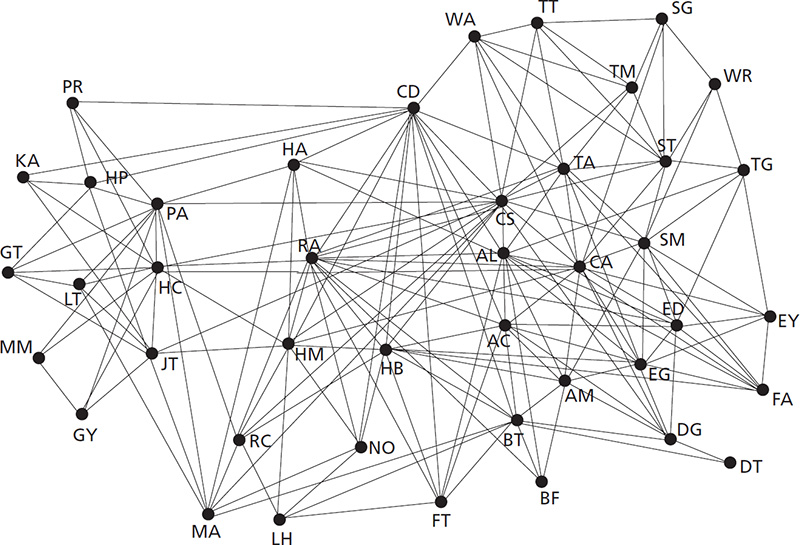

FIGURE 2.3

A de-energizing network

Figure 2.3 shows the de-energizing network in the same organization. These people are rated as a 1 or 2 on the 7-point Likert scale. They are de-energizing others—sucking the life out of the system—and producing negative relational energy. As you can see, several senior-level people (squares) are de-energizing many other employees (for example, numbers 10, 16, 19, and 29) and diminishing others in their interactions.

In the upper-left corner of the network map are two people (numbers 26 and 28) who do not de-energize anyone. No one rates either person as a 1 or 2 on the Likert scale. These two people, however, are the only employees in the organization with no negative ratings. The implication is that most people are not merely energizers or de-energizers. Rather, most people energize some people and de-energize others. Energizing is not an all-or-nothing condition. In fact, a similar ratio exists with positive communication and energizing. If you energize three to five more people than you de-energize, you have an overall positive, energizing effect on the organization.5

In another organization I studied, almost all of the senior managers were rated by employees as de-energizers. A majority of people in senior-level positions were given a 1 or 2 rating in the survey of interactions. After being shown these data, the company, to its credit, announced the initiation of a program to develop positively energizing leadership among its senior managers.

The most important point is that positive energy is a set of behaviors that can be developed. Positive energy is not just personal charisma. It is not just extroversion or a personality dimension. It is not just physical attractiveness. Positive energy is defined by a set of behaviors that anyone can learn and develop. Some key attributes of positive energy and some suggestions for how to develop positively energizing leadership are provided in chapters 3 and 4.

Figure 2.4 shows an information sharing or communication network constructed by my colleague Rob Cross.6 The network map shows who gives information to whom and who gets information from whom. You can see that many communication lines are well used. A lot of information sharing is taking place. Figure 2.5 shows the same information sharing network among the de-energizers. Communication barely exists. That is, people tend not to communicate or interact with people who are de-energizing because the emotional and social costs are so high. It’s exhausting to interact with de-energizers. The statistical relationship between communication and energy, therefore, is positive: the more positive energy, the greater the communication. Both frequency and richness of information sharing increase among positively energizing connections.

FIGURE 2.4

An information sharing network

Source: Used with permission of Rob Cross.

It is also possible to identify the density of an energy network. Density is measured by examining the connections between all possible members of a group or organization. The question is, Of all possible pair-wise connections, how many are positively energizing and how many are de-energizing? When every single person rates every other person in terms of energy, how many of those connections are rated as positively energizing? As may be expected, the denser the positive energy network—that is, the more every person in the network positively energizes every other person in the network—the higher the performance of the organization. Everyone can, in other words, create a positively energizing relationship with other people.7

FIGURE 2.5

Information sharing among de-energizers

Everyone cannot be the most influential person in an organization, of course, nor can every one be the center or hub of an information network. Information and influence resources are limited. On the other hand, everyone can be a positive energizer, not just those occupying senior positions. Any interpersonal connection can become energizing; thus, positive energy is a non-zero-sum game. It can be infinitely expanded in a system.

POSITIVE ENERGY AND PERFORMANCE

Three important conclusions have emerged from research on positive energy in organizations. The first is that people who are positive energizers are higher performers than others. This is not surprising. People who tend to uplift and give life to others are likely to perform better than people who do not. There is a surprise finding, however, that has emerged from my own and my colleague Wayne Baker’s research: a person’s position in the positive energy network is significantly more important in predicting performance than a person’s position in the information or influence network. Energy is substantially more important in accounting for individual performance, and for a unit’s performance, than is information or influence.8

What is important about this finding is that almost all leaders in organizations constantly manage information: “Did you go to the meeting?” “Did you get the memo?” “Do you understand our strategy?” “Are you informed about what we want to get done?” Similarly, managing influence is a critical part of the job of leaders: “Here are the incentives.” “Here are the goals.” “Will you respond to the pressure to meet our targets?”

However, an important question is, Is positive energy ever managed, or managed to the same extent as is information or influence, by leaders? Do people ever get recognized or rewarded or hired or promoted because they are positive energizers? Usually not, because energy is seldom recognized as an important resource. Empirical evidence suggests, however, that energy should get priority because it is substantially more important than what normally receives leaders’ attention.

A second conclusion is that positive energizers impact the performance of those with whom they interact.9 That is, positive energizers account for an inordinate amount of performance because other people tend to flourish in their presence. The heliotropic effect helps explain why. People flourish in the presence of positive energy or life-giving influences. In professional athletic organizations, for example, we have all noticed that teams often trade for players who may be past their peak years of performance but who are needed for the clubhouse. It is well known in professional sports that positive energizers in the locker room can account for team wins that would otherwise not be achieved. This is because positive energizers affect the performance of individuals with whom they interact.

A good example is a friend, Shane Battier, who was drafted into the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 2001. Shane was Player of the Year in high school, was Player of the Year in college, and then played for three teams in the NBA before his retirement in 2014. Battier’s personal statistics were not spectacular as a player, and the media often labeled him as a midlevel player without the needed physical skills to be great. On the other hand, every time Battier was hired by a new team, that team won at least 20 more games than the previous year and made the playoffs. Battier made the NBA finals three times and won twice. One analyst, reviewing Battier’s career, summarized it this way:

When he is on the court, his teammates get better, often a lot better, and his opponents get worse—often a lot worse. He may not grab huge numbers of rebounds, but he has the uncanny ability to improve his teammates’ rebounding. He doesn’t shoot much, but when he does, he takes only the most efficient shots. He also has a knack for getting the ball to teammates who are in position to do the same, and he commits few turnovers. On defense, although he routinely guards the NBA’s most prolific scorers, he significantly reduces their shooting percentages. At the same time, he somehow improves the defensive efficiency of his teammates … helping his team in all sorts of subtle hard-to-measure ways that appear to violate his own personal interests.10

Battier simply helped other teammates perform better on the court than they would have otherwise—a good example of the second conclusion.

A third major conclusion from empirical research is that highly performing organizations have many more positive energizers than normal organizations—as many as three times more. Positive energizers can reside throughout the organization at any hierarchical level. Anyone can learn to display the attributes of a positive energizer, and because performance is so highly dependent on positive energizers, organizations need more of them. Moreover, because positive energy is not a personality trait but rather a set of behavioral attributes, training in the enhancement of positive energy should be an important part of the leadership development agenda. A growing number of organizations have found this energizing development strategy to be highly effective in producing above-average bottom-line performance. (Chapter 4 addresses the development of positively energizing leadership.)

It is true that short-term results can be achieved by de-energizing leaders or individuals who deplete and diminish other people. Several well-known leaders in highly recognized organizations seem to have achieved high levels of success without being positively energizing to those around them. But, in the long run, and as pointed out by Toshi Harada in chapter 1, inefficiencies, protective behaviors, wasted energy, diminished information flows, lower levels of innovation, less psychological safety, and increased defensiveness will mitigate the level of performance that could have been achieved in the presence of positive energy. The research is clear that positive energy matters a lot, and it especially matters in leaders.

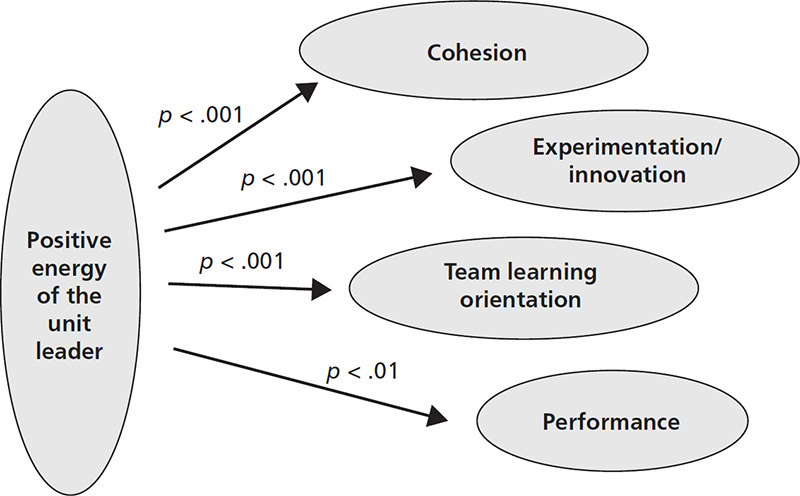

Figure 2.6 reports the results of one particular study my colleagues and I conducted with more than 200 employees who rated the positive energy they experienced when they interacted with the leader of their own organizations. A five-item scale was used:

FIGURE 2.6

Impact of positively energizing leaders on employees

• I feel invigorated when I interact with this person.

• After interacting with this person I feel more energy to do my work.

• I feel increased vitality when I interact with this person.

• I would go to this person when I need to be “pepped up.”

• After an exchange with this person I feel more stamina to do my work.

The results demonstrate the effects of positively energizing leaders on their employees’ job satisfaction, well-being, engagement, and performance. The arrows labeled with “p < .001” indicate that the probability that this relationship occurs by chance is less than 1 in 1,000—that is, there is a very strong relationship between the positive energy demonstrated by the unit leader and the outcomes on the right side of the figure. Employees’ job satisfaction, well-being, engagement, and performance are higher when their leader is a positive energizer. One surprising finding was that enrichment of families, or family well-being, is also significantly affected by the positive energy of the work unit leader. Positively energizing leaders had an impact outside the work setting itself, especially on employees’ families.11

FIGURE 2.7

Impact of positively energizing leaders on the organization

In addition, figure 2.7 shows the effects of the energizing leader on the performance of the organization itself. Not only were individuals affected by the leader’s energy, but the bottom-line performance, learning orientation, experimentation and innovation, and cohesion of the organization all were significantly enhanced when they experienced a positively energizing leader.

Knowing that positive energy is an important resource to be managed in organizations, and being convinced that positively energizing leaders have a significant impact on employees and on bottom-line performance, leads us to ask two important questions: How can we identify the positive energizers in our team or organization? What do we look for if we want to hire more positive energizers?

IDENTIFYING POSITIVE ENERGIZERS

On several occasions I have been invited to help senior executives identify the positive energizers in their organizations. This process can often be useful when a senior executive takes on a new role and does not have a history with his or her subordinates. Knowing who the positive energizers are, and who tends to be de-energizing, is a real advantage to a new leader. At least three options exist for helping to identify the positive energizers within a management team.

One option, and the most accurate one, is to ask each person on the management team to rate the relational energy they experience with every other member of the team on a 7-point scale (where 1 is very de-energizing and 7 is very positively energizing). A data matrix will result with ratings associated with every person. A network map12 is created using readily available network mapping software. A variation of figure 2.2 (shown earlier) will result.

A second option is illustrated by a senior executive of a worldwide retail firm who was interested in creating a network map of his top 40 executives. He was new to the role and eager to identify the energizers in his leadership team. We began by asking each member of his 40-person team to rate the other 39 members. However, within an hour of distributing the request, he received phone calls from several of his team members. They indicated that they were happy to do the ratings but wanted them to be confidential. They did not want other team members to know how the relationship was being rated.

This, of course, eliminates the possibility of creating a network map, because there is no way to draw lines between two anonymous individuals. A second option was used, therefore, to identify the positive energizers in the top team.

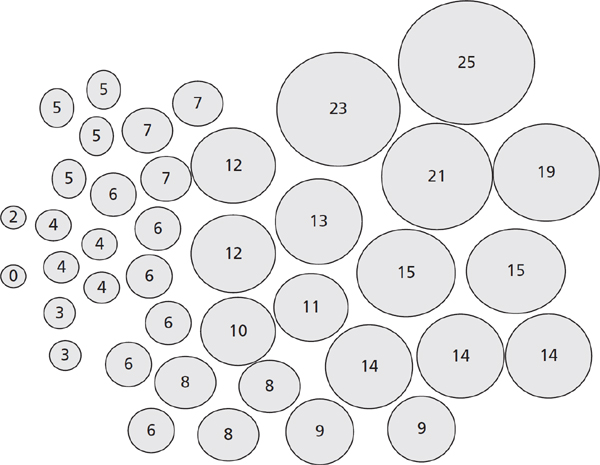

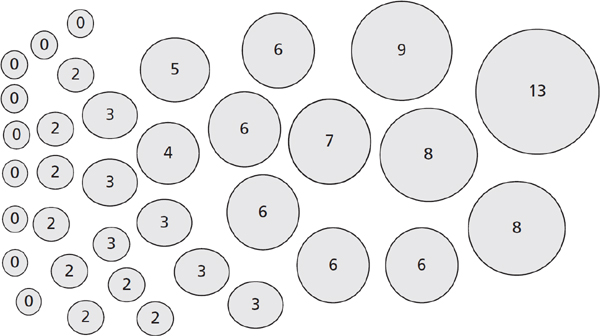

Each of the top 40 people still rated each other member of the team, but feedback to the entire leadership team and to each individual showed just the number of individuals who were rated as 6 and 7 (indicating highly energizing relationships) as well as the number who were rated as 1 and 2 (indicating de-energizing relationships). Figures 2.8 and 2.9 show the results of the ratings.

In figure 2.8, each bubble represents a member of the top management team, and the number within each bubble is how many times that person was rated by others as highly energizing (6 or 7). One person was rated by 25 other team members as being positively energizing, one person had 23 nominations, one had 21 nominations, and so forth. One member of the top team received no ratings of positively energizing. In figure 2.9, 9 members of the team had no one rate them as de-energizing, but one person had 13 nominations as a de-energizer, one had 9 nominations, two had 8 nominations, and so forth.

FIGURE 2.8

The positively energizing leaders

These data were shared in an anonymous fashion with the entire team of 40, and each individual was given his or her own data. Each person also had a chance to receive one-to-one coaching regarding his or her ratings to assist with interpretation and to help provide developmental opportunities if desired. The CEO received all the data, including the individual ratings of each person.

FIGURE 2.9

The de-energizing leaders

The value of this information for the CEO included his ability to more fully and more accurately identify the energizers and the de-energizers in his top team and to provide developmental experiences to enhance the density of the network. He was able to mobilize the positively energizing members of his team to help lead change initiatives and foster commitment to his strategic plan. He was also able to identify those who were likely to generate resistance and/or who needed to be coached to become more valued members of his team. (Chapter 4 also discusses action implications for these kinds of data.)

This second option for identifying positive energizers is known as a “bubble chart” and can be readily performed in a short amount of time. Simply ask all members of the group to name the two most positively energizing people in the group, either by writing the names on a slip of paper or by emailing the names to you. Count the number of nominations each person receives. A bubble chart is an easy way to display the results anonymously. It allows the leader to learn who the most positively energizing people in the group are, and the group gets a general sense of the energy network in the room. These data can be collected in 10 minutes in real time.

A third option is a pulse survey. Some CEOs send a weekly email to their employees asking this question: On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your energy today? If the Tokyo office previously averaged 9.3 and it is now at 7.8, the CEO shows up to help diagnose issues and boost the group’s energy. The energy of employees is monitored on a weekly basis using a one-question email so that a picture of the collective energy of a group can be examined.

HIRING POSITIVE ENERGIZERS

If we need to supplement our current team or organization with more positively energizing people, what do we look for? What kinds of questions could we ask to find positive energizers to hire? These questions can be addressed by using an example close to home.

The Department of Management and Organizations at the University of Michigan has been rated among the top management departments in the world for the past decade or so.13 One key reason for this ranking is the criteria used to hire faculty members. Three criteria dominate the selection process. First, a candidate has to be a world-class scholar. His or her research has to make an important scholarly contribution to the discipline. This is no surprise, because producing scholarship is the key role of a research university. Everyone wants world-class scholars.

Second, a candidate must be a good teacher. He or she has to make a difference in students’ lives by the content and pedagogy used in the classroom. This criterion is also no surprise. All world-class universities seek candidates who excel in the classroom and in their scholarship.

The third criterion is the differentiator for the department. The candidate must be a net-positive energizer. This means that candidates must add more positive energy to the system than they extract. No one can be a positive energizer all the time, of course, but the balance has to be in favor of positively energizing other people. This eliminates self-aggrandizing curmudgeons, people who care only about themselves, people who compete to make certain they get the credit, and people who are not willing to invest in their colleagues. The result, over the past 15 years, is that each faculty member in the department invests in and genuinely supports the 15 other people in the department. Each department member is actively committed to helping other department members get better every day. Each faculty member is being positively energized by their colleagues much of the time.

A question that remains, of course, is how to find people to hire who are positive energizers. How can we identify a positively energizing candidate? When the individual is not familiar, how can we know?

One approach is to conduct an interview with the candidate in which specific questions are asked that reveal positive energizing. An example of questions I prefer was adapted from Laura Queen, vice president of organization development and chief development officer at G&W Laboratories. Her questions have been modified, but they illustrate the approach taken to identify positively energizing candidates.

• Describe a role you’ve had that you absolutely loved. Describe why you fell in love with it. What did you learn?

• Describe an organization you’ve worked for that you’ve fallen in love with. What was it about this organization that caused you to love it? What did you learn?

• Describe a project, a work experience, or a challenging situation that exemplifies when you have done your best work. Describe this situation or challenge. What contributed to your success? What did you learn? If you could do it all over again, what would you do differently?

• Describe the best leadership or management team you’ve ever been a part of. What made this team so special? What did you learn?

• Describe the best leader you’ve worked with or worked for. What made this leader so special? What did you learn from this person? What is one gift from this person that you carry with you today?

• Describe a situation in which a coworker or employee needed your assistance to succeed or flourish. How did you help this person achieve his or her highest potential? What did you learn?

• Describe a time when you achieved peak performance, when you have been at your best, or when you have become positively deviant. What did you do? What did you learn?

Many people have a difficult time answering these questions. They have never been in love with any organization or any role. They have never reached peak performance themselves. They have never helped anyone else flourish and reach their highest potential. They have never learned the lessons that are associated with positively deviant performance and positively energizing experiences. They have never been a positive energizer that affected the life of a colleague. These questions help identify individuals who have experienced positive energy and demonstrated it with others.

DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION

Understandably, some may dismiss these questions as irrelevant in the face of current concerns related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Class-action lawsuits, boycotts, civil unrest, and lost employment have intensified concerns about these issues, so some individuals may dismiss a focus on virtuousness and positive relational energy as being irrelevant to their current concerns. Accusations of injustice, privilege, unconscious bias, and systemic racism are, appropriately, receiving a great deal of attention, and questions regarding falling in love with an organization or role, reaching one’s highest potential, or helping someone else flourish may seem beside the point.

At least three approaches have been applied to the concern with improving diversity, equity, and inclusion. One common response is to approach the issue as a demographic problem. The rationale is that it is important to ensure that positions of status, membership, and privilege have representatives from multiple demographic groups. These groups are usually defined on the basis of ethnicity, skin color, gender, personal preferences, handicaps, and so forth. Sometimes formal or informal quotas are used to ensure that demographic diversity and inclusion in organizations occur.

There are distinct advantages of this approach, including ensuring access to higher economic and status positions for traditionally underrepresented groups and opening doors of opportunity for people who may be disadvantaged as a result of their demographic characteristics. In addition, bringing diverse individuals together may help increase understanding, empathy, and innovativeness, which can develop when heterogeneous groups work together.14

A second common response to concerns with diversity, equity, and inclusion is to offer sensitivity training or consciousness-raising education. Helping individuals become aware of their unconscious biases and the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities helps increase understanding and empathy and, hopefully, can lead to policy and behavioral changes. The advantages of this kind of training include an elevated awareness both in individuals and in organizations of the systemic biases and the behaviors that may be offensive to various individuals or groups and that keep them down. These training sessions may also create more cohesive and connected relationships among diverse individuals.

A common concern with these two approaches is that they often do not produce the intended outcomes. One study of 829 firms over three decades found that these approaches actually make things worse, not better.15 Merely putting people together geographically or involving them in awareness-enhancing sessions does not guarantee that behavior will change and that ingrained or systemic bias will be mitigated. Creating demographic quotas and pointing out offensive behavior have often been criticized as ineffective in achieving genuine diversity, equity, and inclusion.

A third approach centers on positively energizing leadership, particularly the demonstration of virtuous behaviors. Individuals who demonstrate generosity, compassion, gratitude, trustworthiness, forgiveness, and kindness toward others are positively energized and renewed. Virtuousness is heliotropic. Virtuous actions produce positive relational energy, so the probability of forming unbiased, authentic, supportive relationships is enhanced. Virtuousness is, by definition, absent motives of recognition, reward, or payback. Virtuous actions are genuine and expressed for their own inherent value, so recipients of virtuous actions do not feel manipulated or co-opted for other purposes. Unbiased, authentic, supportive relationships are enhanced.

In this third approach, all individuals are encouraged to assist others in fulfilling their highest potential as well as working toward reaching their own potential. Hiring decisions are focused on the extent to which individuals are working to reach their own peak performance as well as helping others achieve their potential rather than emphasizing demographic factors. Virtuousness refers to an aspiration in human beings to reach their highest potential, so when leaders demonstrate virtuous behaviors and seek them in others, other individuals are more likely to flourish—to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more. The barriers endemic in racism, injustice, and systemic bias tend to be minimized and replaced with a focus on the best of the human condition—helping each person fulfill his or her highest aspirations. This is one reason why positively energizing leadership is so crucial in attracting positively energizing people and in creating a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

CONCLUSION

A great deal of evidence is available that confirms that positively energizing leadership and positive practices produce successful performance in organizations. Even in industries that normally eschew practices that are not linked to bottom-line results, positively energizing leadership has been shown to have significant positive impact on performance. The display of positive energy in leaders, in fact, has proved to be much more important in predicting performance than the amount of information or influence leaders possess.

Most importantly, the attributes of positively energizing leaders are learned behaviors to which almost anyone has access. That is, everyone has the potential to be a positively energizing leader. The key attributes and behaviors of positively energizing leaders and their impact on organizational performance are discussed in the following chapter.

I am indebted to my colleague Wayne Baker for introducing the concept of positive energy networks discussed in this chapter.