3

ATTRIBUTES OF POSITIVELY ENERGIZING LEADERS

Research confirms that positively energizing leaders are vital in affecting the performance of employees and their organizations. Moreover, positive energy is not merely a personality dimension or inherent attribute; rather, it results from behaviors that anyone can learn and develop. Therefore, a few questions will naturally arise: What does one need to develop to become a positively energizing leader? What are the attributes of positive energizers? Who are the positive energizers in my organization?

This chapter highlights key attributes of positively energizing leaders, provides more empirical evidence regarding their importance in affecting organizational performance, and describes some practices and activities that help foster positive energy in leaders.

ATTRIBUTES OF POSITIVELY ENERGIZING LEADERS

A good summary definition of positively energizing leadership is captured by a (slightly modified) statement originally attributed to the sixth president of the United States, John Quincy Adams (1767–1868):

If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a positively energizing leader.

Positively energizing leaders are not self-aggrandizing, dominant individuals who seek the limelight. They are not always in charge or at the front. They are, rather, individuals who produce growth, development, and improvement among others with whom they interact. They exude a certain kind of light or energy that is uplifting and helps others become their best.

To understand more clearly how Adams’s statement is operationalized by leaders, interviews were conducted with hundreds of leaders identified as positive energizers as well as with other individuals regarding their observations of those energizers. The questions centered on which attributes positively energizing leaders display themselves as well as how positive energizing leadership can be enhanced.

These interviews produced a set of attributes that differentiate positively energizing leaders from others. Table 3.1 lists the most commonly identified attributes of positively energizing leaders emerging from the interviews. This is not a comprehensive list, of course, because circumstances and culture may alter what is most effective in certain organizations. Other attributes may be effective in certain circumstances and in diverse cultures. This list is universal enough, however, that it can guide efforts to develop more positively energizing leadership attributes. None of these 15 attributes was mentioned more often than others in the interviews, so none necessarily predominates above others. The numbering is for reference only and does not imply priority. These items represent the attributes that were most frequently mentioned.

TABLE 3.1

Attributes of positively energizing leaders

Energizers |

De-energizers |

1. Help other people flourish without expecting a payback. |

1. Ensure that they themselves get the credit. |

2. Express gratitude and humility. |

2. Are selfish and resist feedback. |

3. Instill confidence and self-efficacy in others. |

3. Don’t create opportunities for others to be recognized. |

4. Smile frequently. |

4. Are somber and seldom smile. |

5. Forgive weaknesses in others. |

5. Induce guilt or shame in others. |

6. Invest in developing personal relationships. |

6. Don’t invest in personal relationships. |

7. Share plum assignments and recognize others. |

7. Keep the best for themselves. |

8. Listen actively and empathetically. |

8. Dominate the conversation and assert their ideas. |

9. Solve problems. |

9. Create problems. |

10. Mostly see opportunities. |

10. Mostly see roadblocks and are critics. |

11. Clarify meaningfulness and inspire others. |

11. Are indifferent and uncaring. |

12. Are trusting and trustworthy. |

12. Are skeptical and lack integrity. |

13. Are genuine and authentic. |

13. Are superficial and insincere. |

14. Motivate others to exceed performance standards. |

14. Are satisfied with mediocrity or “good enough.” |

15. Mobilize positive energizers who can motivate others. |

15. Ignore energizers who are eager to help. |

A brief explanation of each of these attributes may help highlight their importance in producing positively energizing leadership. When interacting with other people, positively energizing leaders tend to demonstrate the following attributes:

1. Help other people flourish without expecting a payback. Positive energizing is not an exchange relationship. A quid pro quo is not expected or assumed in interactions. Positive energizers contribute altruistically for the benefit of others, without expecting recognition or reward. For example, they may anonymously provide assistance to an employee who is in need or provide coaching and mentoring without expecting acknowledgment or recognition.

2. Express gratitude and humility. They acknowledge the contributions of others and express gratitude often and immediately. Publicly thanking others and recognizing their contributions is almost always an expression of humility as well. For example, they may send personal thank-you notes to individuals with whom they work or to the families of their employees.

3. Instill confidence and self-efficacy in others. They help others feel valued, competent, talented, and completely capable of succeeding. Others feel important in their presence. For example, they may recognize and highlight the talents or abilities of another person, and they may provide support when missteps occur.

4. Frequently smile. This is so simple, but it is the single most noticed attribute of positive energizers. In repose, many people may look like they are angry or sad, so positive energizers make sure to communicate positivity through their facial expressions. For example, when they greet people, they make eye contact and tend to have a pleasant look on their faces.

5. Forgive weaknesses. They see mistakes as learning opportunities. They help others overcome blunders rather than negatively judge them or create guilt. For example, they may point out the positive in others’ miscues or failures and identify ways to improve without inducing shame.

6. Are personal and know outside-of-work interests. They show interest in the whole person, not just the work role. A study at the University of Kansas found that it takes about 50 hours of socializing to progress from an acquaintance to a “casual” friend, an additional 40 hours to become a “real” friend, and a total of 200 hours to become a “close” friend.1 Positively energizing leaders take time to get past the acquaintance phase, to learn about important aspects of employees’ lives outside the work setting, and to treat individuals as whole people, not just titles or functions. For example, they may keep a notebook on individuals’ family members and important personal or family events.

7. Share plum assignments and recognize others’ involvement. They find ways to involve others, to help them find ways to succeed, and to be acknowledged. They are willing to share the limelight without abrogating their own responsibility to lead. For example, they may provide assignments that help other people stretch and grow as well as publicly recognize them for their effort and for their success.

8. Listen actively and empathetically. Rather than being quick to give advice, they sincerely seek to understand, they ask questions, and they give full attention to the other person. They are willing to talk openly and honestly with individuals in face-to-face conversations. For example, they may demonstrate humility in being open to feedback, show sensitivity to personal issues that employees may be facing, and respond compassionately when employees experience hurt or pain.

9. Solve problems rather than create problems. They tend to solve problems even before others know there are problems. They anticipate others’ needs and respond before being asked. For example, they provide assistance before appeals are made, offer resources that may be needed but not requested, or offer know-how and knowledge that avoids a future problem. They take responsibility for generating results.

10. Mostly see opportunities. They tend to be optimistic while being balanced with realism. They find ways to move forward rather than being bogged down in problems or “yeah, buts.” They remain hopeful about a successful future. For example, they approach challenges and difficulties with a “yes, and” rather than a “yeah, but.”

11. Tend to inspire and provide meaning. They clarify a profound purpose in the activities they lead so that others see meaningfulness in the undertakings. They elevate others’ views. For example, they may help others see the profound purpose of successful goal accomplishment and the impact that it can have on other people.

12. Are trusting and trustworthy. Others trust their sincerity and authenticity as well as their dependability. They hold confidences as sacred. They follow through on their word even if it requires sacrifice. For example, they may give others the benefit of the doubt, react charitably, and, when they make a promise, hold their personal honor as more important than a legal contract.

13. Are genuine and authentic. Being positive is not an act, a trick, or a technique. Positive energizers strive to be consistent in their values and behavior. They are willing to be vulnerable with others in demonstrating what is most important to them. For example, they may be willing to acknowledge and appropriately share personal challenges and mistakes, thereby placing themselves in a vulnerable position.

14. Expect very high performance standards. They help others exceed expectations. They motivate others to achieve positive deviance and reach their highest potential. They recognize that good performance seldom wins championships, but that great performance is required. For example, they motivate others to achieve more than they thought possible and to reach a potential that they did not know they possess.

15. Mobilize positive energizers who can motivate others. They seek out positively energizing people to help uplift others around them. They marshal positive energizers to foster improvement and goal accomplishment. For example, they know individuals in their organization who positively energize others, and they mobilize them to help achieve needed outcomes and changes.

Not every positively energizing leader is characterized by all of these attributes, of course, and some attributes of de-energizers may not be entirely absent from positively energizing leaders. It is clear, however, that de-energizing behaviors diminish positive energy and reduce the effectiveness of leaders in relation to their employees. Most of these attributes are recognizable in individuals who are judged to be positively energizing, and, importantly, this list of attributes is not uncommon. None of the attributes is beyond the reach of most individuals. It is possible for almost anyone to develop these characteristics and, therefore, to develop attributes of positively energizing leadership.

The point is, positive energy can be developed and shared with everyone. And, most importantly, the research is clear: when leaders display these attributes, organizations flourish more than when the attributes are absent.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

This last statement is verified by my own research on these attributes of positive energizers. A sample of 600 middle- and upper-management employees in organizations from a variety of industries (e.g., government, finance, construction, education, arts, and entertainment) was investigated. A version of the survey instrument is reproduced in resource 1. Respondents rated the leaders of their organizations on the 15 attributes of positively energizing leadership. They also provided organizational performance data on five dimensions: productivity (achieving targets and goals; accomplishing desired outcomes), quality (mistake- and error-free; on time or ahead of schedule), employee morale (satisfied, engaged employees; low turnover), customer satisfaction (loyal customers; few if any complaints), and financial strength (strong revenues; income exceeds expenditures).

The results showed that the higher the scores on the energizing attributes, the higher the organizations’ performance scores in those five outcomes. (See resource 1.) In particular, especially strong predictive power was associated with the attributes numbered 11 through 15 in table 3.1. That is, positive leaders who inspire and provide meaning, who are trusting and trustworthy, who are genuine and authentic, who expect very high performance standards, and who gather positive energizers that can motivate others have the strongest impact on organizational effectiveness. All of the attributes of positively energizing leaders were found to be important and predictive, but these five were especially powerful predictors of organizational success. In addition, productivity, employee morale, and customer satisfaction outcomes were the most strongly affected by positively energizing leaders. Quality and financial strength of the organizations had slightly less strong associations, although the associations were statistically significant. Figure 3.1 provides a summary of these findings.

These findings highlight the fact that positively energizing leaders do not need to display superhuman attributes. They are individuals who simply display behaviors that we all admire: inspiring others, showing integrity, and being genuine. They expect us to be better. And they involve others in accomplishing desired outcomes. As a result, the organizations they lead perform significantly better than industry averages.

RELATIONSHIPS, VIRTUOUSNESS, AND ENERGY

The attributes associated with positive outcomes in organizations are also the attributes associated with positive relationships. Relationships are more uplifting and life-giving when these attributes are present compared with when they are not. It is also important to note that positive relationships can be relatively momentary (as in a brief interaction with a cashier, a receptionist, or a passerby on the street) or enduring interactions with someone with whom we work or live over time. Both short-term and long-term relationships matter, and even onetime, short-lived interactions can be positively energizing or energy depleting.

FIGURE 3.1

The strongest associations between energizing attributes and organizational performance

The characteristics of enriching, positive relationships have been addressed in a large array of scholarly and popular literature, and exceptionally excellent work has been conducted by my colleagues Jane Dutton,2 Wayne Baker,3 Gretchen Spreitzer,4 and Jody Gittell5 as well as by the Relational Coordination Network. In their work, these scholars focus on high-quality connections (momentary interactions), flourishing interactions, enduring associations, and relational coordination (the mutually reinforcing process of communicating and relating for the purpose of task accomplishment). The work of these scholars has had a major impact on understanding the literature on relational energy, and I encourage you to learn more about their work from the references at the end of the book.

In brief, this work shows that positive relationships are enablers of above-average outcomes physiologically, psychologically, emotionally, and organizationally. For example, evidence links the positive effects of social relationships with social phenomena such as career mobility,6 mentoring and resource acquisition,7 power,8 and social capital.9 Studies also show that positive social relationships have significant effects on longevity and recovery from illness.10 That is, positive social relationships—the uplifting connections associated with individuals’ interpersonal interactions—have beneficial effects on a variety of aspects of human behavior and health.

This chapter supplements the work of these colleagues by focusing on a set of attributes and behaviors that have received much less attention in leadership research. The primary intent of this discussion is to complement the literature regarding how to build and foster positively energizing relationships.

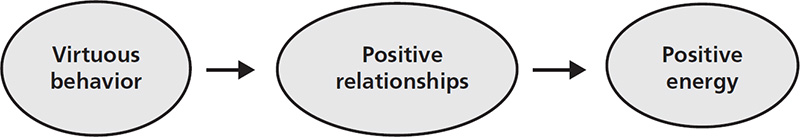

Figure 3.2 summarizes a set of behaviors that are especially important in producing positively energizing leadership but that have received sparse attention in the literature on leadership and organizational performance. Specifically, this discussion demonstrates that virtuous behavior is among the most important factors leading to flourishing relationships, which, in turn, lead to positive energy. Many of the attributes of positive energizers that emerged from our interviews in table 3.1, as it turns out, are consistent with what is often labeled as virtuous behavior.

FIGURE 3.2

Virtuousness, relationships, and positive energy

VIRTUOUSNESS

The concept of virtuousness is rooted in the Latin word virtus, or the Greek arête, meaning “excellence.” More recently, virtuousness has been described as representing the best of the human condition, the most ennobling behaviors and outcomes of people, the excellence and essence of humankind, and the highest aspirations of human beings.11 Thomas Aquinas,12 Aristotle,13 and many other well-known philosophers proposed that virtuousness is rooted in human character and represents what human beings ought to be, humankind’s inherent goodness, humanity’s very best qualities, or being in complete harmony with the will of God. Virtuousness—the highest aspirations to which human beings aspire—is a commonly accepted standard in all cultures.14 Whereas the nature of its demonstration may differ across cultures, virtuousness is universally agreed upon as good for all.15 It serves as a stable, consensual standard, especially in times characterized by VUCA.

In functional terms, virtuousness is claimed to be evolutionarily developed because it allows people to live together, pursue collective ends, and protect against those who endanger the social order.16 Thus, from a genetic or biological perspective, virtuousness plays a role in the development and perpetuation of humanity. This also explains why virtuousness is highly prized and admired, and why virtuous individuals are almost universally revered, emulated, and even sainted. They help perpetuate the human species.17 Miller pointed out that a selective genetic bias for human moral virtuousness exists.18 He argued that even mate selection evolved at least partly on the basis of displays of virtuousness.

This explains why virtuousness and the heliotropic effect are so closely connected. Virtuous actions are life-giving and life-perpetuating, and this is the same definition associated with the heliotropic effect given in chapter 1. Human beings are inherently inclined toward that which gives or enables life, and, as it turns out, virtuousness is also heliotropic.

Several scholars have provided evidence that the human inclination toward virtuousness is inherent and evolutionarily developed.19 Some have proposed, for example, that inherent virtuousness develops in the brain before the development of language.20 Neurobiological studies show that individuals have a basic instinct toward morality and are organically inclined to be virtuous.21 One study asserted that all human beings are “genetically disposed” to acts of virtuousness, and observing and experiencing virtuousness helps unlock the human predisposition toward behaving in ways that benefit others.22

Studies demonstrate, for example, that even before children are old enough to learn about civil behavior, they have inclinations toward fairness, generosity, and compassion. Infants as young as three months old exhibited behaviors indicative of moral virtue in experiments with puppets. When given a choice between a helpful, virtuous puppet and a puppet that did not help or that hindered another, children overwhelmingly preferred puppets that exhibited helpful, generous, and virtuous behavior.

Other studies confirm that children as young as 10 months old demonstrate virtuous behaviors (including generosity, altruism, fairness, and cooperation) when put in situations in which a choice was provided to them. The children in this study demonstrated inherent generosity, even more than that demonstrated by their more rational parents.23

Another study of 19-month-old children (the age at which children are most prone to exhibit temper tantrums and physical aggression when they do not get what they want) revealed that most children exhibited generosity even when they were disadvantaged by doing so. For example, a majority of children who had missed lunch and were especially hungry returned a fruit treat to another person who expressed a desire for it.24

Another set of studies has also demonstrated the benefits of virtuousness on heart rhythms and physiological coherence, which, in turn, predict longevity in life.25 Heart rhythm oscillation is more stable and predictable when individuals are in a virtuous state. In addition, in an earlier book, Positive Leadership, I report a variety of positive physiological effects that are associated with virtuousness, such as wound healing, cortisol levels, experienced pain, and brain activation in ADHD children.26

ON THE OTHER HAND

Whereas virtuousness is heliotropic, common human experience as well as scientific evidence also support the idea that individuals have a strong reaction to negative experiences. One authoritative and comprehensive review from 2001 describes what we now call a human negativity bias. Baumeister and colleagues articulated the conclusion of their literature review with the article’s title: “Bad Is Stronger Than Good.”27 Their review concluded that human beings react more strongly to negative phenomena than to positive phenomena or to stimuli that threaten their existence or signal maladaptation. Negative events have a greater impact than positive events of the same type (e.g., losing friends or money has a larger impact than winning friends or money; it takes longer for negative emotions to dissipate; less information is needed to confirm a negative trait in others; people spend more thought time on negative relationships than positive ones). This raises the question, How can virtuousness and positive energy be heliotropic if bad is stronger than good?

In three controlled experiments, Wang, Galinsky, and Murnighan found that a bias toward the negative has its strongest effects on emotions and psychological reactions, whereas reaction to the positive has its strongest effects on behavior. These authors concluded that “bad affects evaluations more than good does, but that good affects behavior more than bad does.”28 In other words, feelings are strongly affected when bad things happen, but behaviors are most strongly affected when good things happen. Negative energy makes us feel bad. Positive energy helps us take positive action.

A paradox exists in human experience, in other words.29 Both positive inclinations and negative sensitivities exist simultaneously in human beings, and both are potential enablers of positive outcomes. Some of the greatest triumphs, most noble virtues, and highest achievements have resulted from the presence of the negative. Moreover, as people encounter danger, threats, and harm, their survival instincts lead them to pay attention to the negative. Bad takes precedence over good in the short run in order to survive, and negative energy gets more attention than positive energy. In such circumstances, people learn to minimize or ignore positive phenomena. In fact, they tend to negatively label anything positive as touchy-feely, soft, squishy, and irrelevant. They learn to ignore their natural heliotropic tendencies toward positive energy and toward virtuous behaviors.

One implication of this tendency to emphasize the negative in crisis situations is that conscious attention must be focused on positive relational energy and on virtuous behavior in order to overcome the powerful emotional effects of negative energy and threatening behavior. Negativity can become dominant, so virtuousness must be consciously pursued in order to produce life-giving, positive relational energy. Virtuousness lies at the core of the human experience (it is heliotropic), but it can easily be ignored in the presence of short-term crises.

CONCLUSION

The empirical evidence is strong that virtuousness is heliotropic in the sense that human beings are inherently inclined toward virtuous behavior; virtuous behavior is a key element in creating strong, flourishing relationships; and these relationships produce positive outcomes. An important point needs to be made, however, regarding this discussion of virtuousness.

Virtuousness, by definition, is inherently valued for its own sake. Virtuousness is not a means to obtain another more desirable end, but it is a valued end in itself. In fact, virtuousness in pursuit of another more attractive outcome ceases, by definition, to be virtuous. Gratitude, generosity, and integrity in search of recompense are not virtuous. If kindness toward employees is fostered in an organization, for example, solely to obtain a payback or an advantage, it ceases to be kindness and is, instead, manipulation. Virtuousness is associated with social betterment, but this betterment extends beyond mere self-interested benefit. Virtuousness creates social value that transcends the instrumental desires of the actor.30 Virtuous actions produce an advantage to others in addition to, or even exclusive of, recognition, benefit, or advantage to the actor.31

Knowing the attributes of positively energizing leaders, and knowing that displaying virtuous behavior produces positive energy begs the questions: What can be done, specifically, to help develop positively energizing leadership? What actions can be taken? What training can be designed?

In the next chapter, I provide some specific ideas for developing positively energizing leadership. These suggestions are only a sampling of the possibilities for leadership development, of course, but they are behaviors that have proved useful in fostering virtuousness and positive relational energy.