Key 4

Choose High-Leverage Opportunities

My job is to put the best people on the biggest opportunities and the best allocation of dollars in the right places.

—Jack Welch, quoted in Jack Welch and the GE Way by Robert Slater

One day on her lunch hour, Cheryl Krueger was walking in Manhattan when she saw a line of people wrapped around a street corner. The line ended at David’s Cookies, which was selling lumpy, moist, delicious cookies reminiscent of her grandmother’s.

Krueger had learned from her grandma how to make such cookies, so when she discovered that David’s Cookies was selling franchises, she arranged to meet the owner. In a 20-minute meeting, she discovered that he wanted a franchise fee of $250,000 as well as 10 percent of the gross and that Krueger would have to buy all her cookie dough from him and pay for the shipping.

On the plane back to Columbus, Ohio, her home town, Krueger pictured the people standing in line. The cookie business would give her control of her life. But, after a hard analysis of the numbers, she calculated that she would have to sell a million dollars worth of cookies a year to make a profit. She began to wonder what she would be getting for the franchise costs. From her creative marketing expertise came the question: Did the name David’s Cookies mean anything in Columbus? She spent the weekend asking people if David’s Cookies meant anything to them. None of them knew the name.

A Business Idea Is Born

So Krueger created a business plan for her own company, Cheryl&Co, and approached the banks. The banks asked why people would buy cookies when they could bake them. She told them that many women were busy with careers and weren’t baking much anymore. When the banks turned her down, she decided to finance the business herself.

For three years after she opened her first Cheryl&Co store, Krueger continued working in New York as a clothing company executive. Each Friday, she flew to Columbus, worked in her store over the weekend, and returned to New York on a flight early Monday morning. When the first store could support her, she quit her executive job and opened a second store.

As the number of stores increased, Krueger found a valuable opportunity to create a central baking operation to supply all the Cheryl&Co stores. That led to another opportunity. The retail dessert business was highly seasonal, and she did not like to lay off employees during the off-peak periods in her bakery. So, to level out her bakery orders, she sold private-label desserts to restaurants that served desserts all year long, such as Bob Evans, Ruby Tuesday’s, and Max & Erma’s. Then a few travel agencies began giving her cookies to airline representatives. The airlines liked the cookies and asked her to wrap them individually for their passengers.

Today, Cheryl&Co supplies cookies to many companies, such as Delta Airlines, US Airways, The Limited, and the Walt Disney Company. When Hallmark decided to become the premier gift company, it not only chose Cheryl&Co as its dessert supplier but also took a minority interest in her company. Using her expertise and her ability to select only the most valuable opportunities, Krueger has built Cheryl&Co into a successful, multimillion-dollar enterprise.

To explain how people like Krueger discern great opportunities from poor ones, we need to answer three questions:

- How do you select high-leverage opportunities?

- How do you eliminate low-leverage or wasteful activity?

- How do you eliminate the cost of lost opportunity?

Let’s look at each of these questions.

How Do You Find and Seize High-Leverage Opportunities?

Krueger knew the difference between a poor opportunity and a great one because of her extensive expertise and her high-leverage thinking. She had learned about purchasing and the art of negotiation as an assistant buyer at Burdine’s department store. She had learned retail merchandising and management during four years as merchandising manager at The Limited. She had gained business experience as an assistant vice president with Claus Sportswear.

Thus, with all this experience, before Krueger started her own retail business:

- She had learned how to prove that something would sell, that it could be purchased at the right price and quality, and that it would sell for a profit.

- She had learned how things were made, distributed, promoted, and sold.

- She had learned how to realistically forecast, survey, estimate, and analyze the likely success of an opportunity.

Calculating Benefits Versus Costs

Many see what appears to be a great opportunity for success and then fail when they go after it because they see only the benefits and they underestimate the costs. Krueger says, “What separates a winner from a loser is the ability to be realistic, to do the hard numbers, to be as tough with themselves as a boss would be. And it’s easier to be realistic when it’s your own money at risk” (from an interview with one of the contributors to this book).

There are many opportunities for success. However, before deciding to seize an opportunity, successful people and successful businesses try to predict how much long-term benefit they would get from it compared with the time, brainpower, and other resources they would have to spend on it.

To select only great opportunities, you must do two things:

- First, you must determine if the opportunity is one of the best opportunities to meet your long-term goals.

- Second, you must calculate the overall value of the opportunity.

The overall value of an opportunity is the expected future benefit of the opportunity minus the costs of seizing it. For example, Krueger expected to create a long-term business that she would love to run and would provide her with lifetime earnings. For that, she was willing to sacrifice a number of years in the beginning, when she put her time and money into the business but had no returns.

To calculate future benefits, risk must be considered. If the opportunity has only a 50-50 chance of success, the expected future benefits are cut in half.

Expected Future Benefits Versus Resources

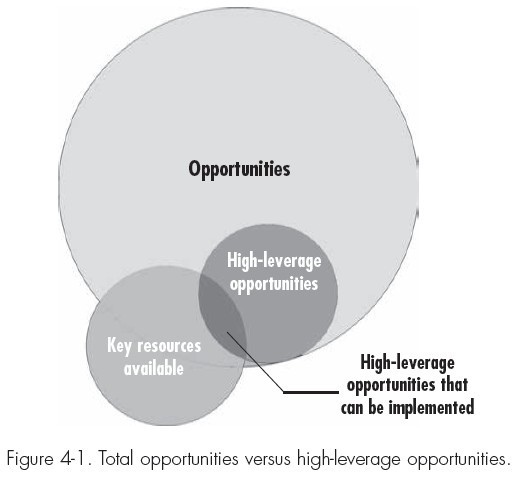

Even if the opportunity is a very good fit with your long-term goals, and its overall value is high, it may not be the best opportunity in which to invest your resources. Another calculation is needed to find the best opportunity. Figure 4-1 shows that only a portion of opportunities can be pursued with available resources, and thus they should be chosen carefully.

Thinkers like Krueger get an expectation of the return they’ll get on the resources they invest by dividing the expected future benefits by the resources required to seize the benefits. The expected future benefits include the increased value and the contribution to long-term strategy, freedom, money, or whatever the seizer considers valuable. Resources include time, money, effort, and whatever is required to seize the benefits.

With regard to short-term versus long-term thinking, many people want short-term payoffs. They won’t devote time to preparation, because it doesn’t pay off immediately. Because the great achievers knew the long-term value of preparation, they spent their time, thoughts, and resources on activities that had the best combination of short-term and long-term returns.

How Do You Eliminate Wasteful Activity?

The great achievers have known that most activities, events, and transactions in life are wasteful. For instance, Darwin Smith, the CEO of Kimberly-Clark, concluded that annual forecasts of earnings, a Wall Street tradition, focused too much on the short term and provided no real value to stockholders, so he stopped doing them. He also eliminated titles and management layers before the idea was popular. Under Smith, Kimberly-Clark’s stock outperformed those of the other leading paper products companies by four to one. For more on the Kimberly-Clark story, see Good to Great by Jim Collins (New York: HarperCollins, 2001).

So, before committing resources to seize an opportunity, the great achievers have made sure that a potential opportunity is the best one to lead them to success. They have all asked several basic questions to increase their chances of success:

- Is this opportunity the largest benefit we can get from our resources?

- Is it worth far more than the time and resources needed to achieve it?

- Can it be done?

- Is it a source of passion for us?

As discussed above, to produce the best results, more resources should be focused on opportunities than on problems. The great achievers have known both where and how to focus resources and where not to focus them. Even when you decide to focus resources on a high-leverage opportunity, you can’t do it if wasteful activity fills the day.

Guidelines for Determining if an Activity Is Wasteful

The most important guideline for determining if an activity is wasteful is: It’s probably wasteful if you do it routinely without thinking about it—for example, if you do it only because it’s

- a problem or a nagging concern

- in your mail, email, or phone messages

- traditional or habitual

- the first solution that pops up

- a policy without regard to its benefits and costs

- a regular meeting

- the popular thing to do

- a solution that always worked in the past.

You’ve heard people say, “I’m keeping busy.” Keeping busy, being active, and “getting things done” pleases many people. However, we should heed the advice of the great basketball coach John Wooden, who said that we must not mistake activity for achievement.

The goal is to pick opportunities that best fit your long-term strategic goals and also have both high, overall value and a high return on your investments of time, brainpower, and resources. Furthermore, as a person gains greater responsibility and influence, he or she should choose opportunities that also have higher overall value.

Although people and organizations don’t intentionally waste resources on low-benefit, high-cost activities, they don’t always focus on high-leverage opportunities. They naturally drift toward low-leverage ones, which are easier to find, more plentiful, and easier to implement.

Acceptable Opportunities

Here’s a test to do before deciding to seize an opportunity: Estimate the lowest reasonable benefits to be expected from the opportunity. Then divide the lowest reasonable benefits by an estimate of the highest reasonable costs to seize the benefits. Most people do the opposite. They calculate the most optimistic benefits with the least cost. The former test is a pessimistic—but safer—approach.

Whether you should take an optimistic or pessimistic approach depends on your level of expertise in the field where you find the opportunity. If you’re an expert in this field and can make realistic estimates of benefits and costs, an optimistic approach is appropriate. Risk and available resources also must be considered. The pessimistic test is a guideline instead of a formula to use without judgment.

Small Versus Large Improvements

Although It may seem that this book is focusing primarily on large opportunities, we encourage people to find opportunities to make small improvements as well as large ones. A number of small improvements can add up to big improvements over time. Valuable opportunities for improvement come in all sizes. The smallest opportunity for improvement is valuable if its long-term benefits are greater than the cost of seizing it.

On the one hand, much overall value can be gained from seizing many small opportunities. On the other hand, seizing a few large opportunities or even one great opportunity can produce the same overall value to a person or an organization. The highest-achieving organizations train their people to seize opportunities of all sizes as long as the value of the opportunities is larger than the time, effort, and resources required to seize them.

Every individual in an organization should be trained to focus on activities that produce the best chance for success, because all wasteful activities, no matter how small or how large, use up time and resources that would be better spent on valuable activities. The result is lost opportunity.

How Do You Eliminate the Cost of Lost Opportunity?

When you spend your time, brainpower, and resources on low-leverage activity, you lose the benefits you could have gained if you had spent the time, brainpower, and resources on finding and seizing high-leverage opportunities. This is the cost of lost opportunity. If your organization has competitors, you and your organization fall behind when you lose opportunity.

The Limits of Cost/Benefit Calculations

Every worthwhile activity can’t easily be related to long-term benefits. For example, if someone proposes a small improvement that eliminates wasteful activity in an office procedure, it might not go directly to the bottom line. But by encouraging people to make those changes, you develop an organization that is always finding and seizing opportunities. Then, when you’re ready to make large improvements, people are more willing.

Earlier in the chapter that discussed Key 2, we pointed out how research shows that when people or organizations are in the process of preparing for, finding, and seizing opportunities for success, they learn at a higher rate and with higher quality. And when they’re guided by all 10 keys, they’re on the path to success.

How Much Time Should You Invest?

We have been asked if we have discovered a guideline for the percentage of time and activity that individuals and organizations should invest in preparing for, finding, and seizing opportunities. Successful organizations in fast-changing business markets spend at least 20 percent of their total time and activity. Although we don’t have exact numbers, the semiconductor and telecommunications industries spend more than that proportion. Startup businesses run as high as 80 percent. The greater the speed of change in your market or the greater amount you must learn in a short time, the greater the share of your time you should spend on finding and seizing opportunities.

Always Search for a Higher Peak

We are on the path of the great achievers if we are preparing for, finding, and seizing the most valuable opportunities, large or small, within our influence. The great achievers searched until they were satisfied that they had found the highest-leverage opportunities within their areas. Like mountain climbers, they searched through the clouds for the highest peaks. We know one top executive who has a method for selecting high-leverage projects. When anyone in her organization proposes that the company invest in a project, she always asks if they could think of any better opportunity. That way, she asks them to always search for a higher peak.

Summary of Keys 1 through 4

To summarize keys 1 through 4:

- First, the great achievers differentiated themselves by choosing to search for opportunity where they had the best chances of finding a great opportunity.

- Second, they became experts through power learning.

- Third, they taught themselves to be exceptional visionaries.

- Fourth, they worked only on opportunities that had the best chances of making them successful compared with the time, brainpower, and resources they had to use to seize them. Figure 4-2 shows how high-leverage knowledge can be applied to pursue high-leverage opportunities. The greater the amount of targeted knowledge, the greater the chances of recognizing and being able to pursue the greatest opportunities.

In the success stories discussed so far, leaders such as Edison, Curie, Walton, Krueger, and Gates knew how to obtain the willing support of others for the projects they chose to make them successful. Our research findings were quite clear on how the great achievers gathered the support of others and why many other opportunity finders stumbled or fell at this point.

Obtaining the Willing Support of Others

The best leaders studied how other great leaders were able to harness the power of others. They discovered three more keys. Guided by these keys, they were able to mobilize the support they needed. The art and science of these keys is the second leg of the path, which makes up part II of this book.

Remember that learning is more powerful when you learn in the pursuit of opportunity. So to prepare for the second leg of this learning journey, imagine that you’ve found a great opportunity for success. However, to seize it, you will need the time and resources of others, who often are less than willing.

Self-Evaluation Exercises

Self-Evaluation Exercises

Select the Best Opportunities for Success

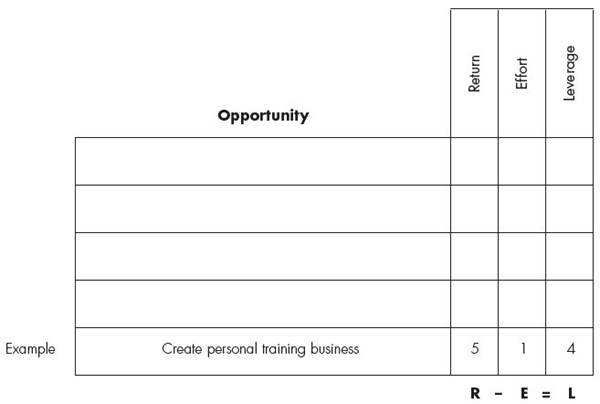

Below, list several opportunities identified from earlier exercises or other opportunities from your business or personal life. First, rate them 1 to 5 in the “return” category, with 5 being the highest potential for expected return. Next, rate them 1 to 5 in the “effort” category, with 5 being the highest effort required.

In the “leverage” (L) column, subtract the effort ranking value (E) from the return ranking value (R) and place the result in the leverage column for each row—as shown in the formula R – E = L. The highest numbers in the leverage column are likely your high-leverage opportunities.

Maximizing Your Ability to Pursue High-Leverage Opportunities

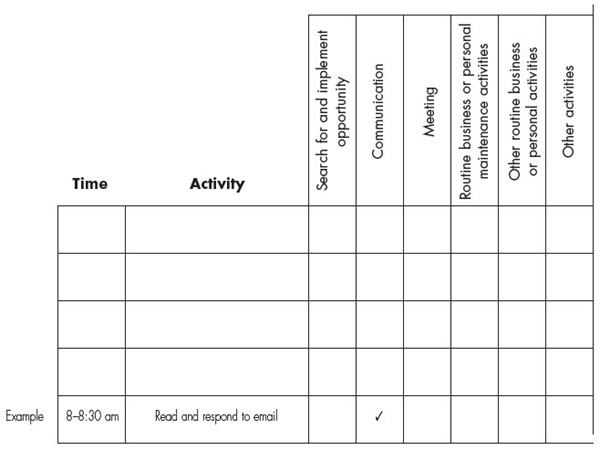

Find out how much time you use in pursuing opportunities. Decide what is the most productive part of your day. This is the time when you have the greatest alertness and potential for creativity and focus. You may need to experiment, because it may currently be occupied with other activities that don’t require high-leverage thinking. Many people will say they are most productive in early morning, somewhere around the first two hours after waking up. Others may have the most productive potential hours at night after the kids are in bed and when the house is quiet. Dissect an average day to find those two or so optimal hours; use an actual day, if possible. List the amount of time consumed by each activity, give a description of the activity, and place a check next to the category to the right that best describes it.

Compare the activities listed above with the opportunities listed in the previous exercise. For most, these precious, high-productivity potential hours of the day are used for activities other than pursuing high-leverage opportunities. Discover how you could rearrange your schedule so that you can use this productive part of the day for creative preparation, finding or seizing activities to support your opportunities.