Key 9

Design, Plan, and Execute

Think of the end before the beginning.

—Leonardo da Vinci

In 1954, Sol Price, a young lawyer, opened a discount store. Everything went well until he discounted bottled alcoholic beverages. He was threatened with jail and hit with a major lawsuit from the alcoholic beverage industry. He fought back and survived a hurricane of lawsuits. He narrowly escaped jail, but he won against all odds and built a $300 million chain of stores called FedMart. In 1974, he sold the chain with the agreement that he and his sons would continue as top executives. Within a year, the new owner fired them.

Price felt betrayed. Nevertheless, as the great achievers always did, he searched until he found another opportunity. He found that small retailers couldn’t make any profit selling cigarettes, candy, and soft drinks. Wholesalers were charging them a 25 percent markup because their orders were small. Price and his son Robert believed that if they could design a wholesale business that was profitable at a 10 percent markup on small orders, they could capture the small retailer market. For more on the Prices’ story, see Profiles of Genius by Gene N. Landrum (Buffalo: Prometheus Books, 1993).

Why Design Matters—and Is Natural

After finding the opportunity, Sol and Robert Price used a design process that is used by great designers and anyone who wants to seize opportunities. We know that a lot of people don’t feel capable of design. But we are natural designers. Watch a child build with blocks or plan a tea party. That’s design. Whether you plant a garden or create a plan to attract investors, you’re designing. We design our lives, or they’re designed for us. But many opportunity finders fail to seize opportunity because they don’t have a good design process.

Once the opportunity has been found, the designer’s job is to create whatever is needed—a new product, process, system, or organization—that will fulfill the opportunity. To do this, the designer must answer three questions:

- What is the purpose of the design, and who benefits?

- How do we create the best design?

- How do we ensure that the design will work?

In our research, we studied the processes of the best designers and boiled them down to three phases, each answering one of these questions. A great designer will consider the first question to be the most important one.

First Phase: What Is the Purpose of the Design, and Who Benefits?

The great designer Leonardo da Vinci once said, “Always think of the end before the beginning.” Although it may seem obvious that the first phase should focus on the end purpose, often the questions about purpose and beneficiaries are not well-answered before design work begins. Steven Covey identifies “beginning with the end in mind” as a habit of highly successful people and a guideline for life design; see his book The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People (New York: Fireside, 1989).

The Prices’ end purpose was a business that made a profit providing small orders of name-brand goods, at a 10 percent markup, to small retailers, so they could compete with large retailers. To meet that purpose, their design would have to eliminate credit card fees, costs of giving people credit, shipping-breakdown costs, trucking costs, delivery costs, and outside-sales costs. Also, inventory and leasing costs would have to be low.

The first phase of design always involves finding the purpose. For example, see the sidebar on Sidney Lumet’s filmmaking.

Before they finish the first phase, master designers analyze their work to check that the design concept matches their purpose. Here’s a checklist used by the great achievers:

- Is the opportunity high leverage?

- Is there a real or perceived need for what we’re designing? Does the design have high meaning and high value to customers?

- Do we have a good estimate of the benefits to the customer?

- Have we designed the product with enough uniqueness to attract customers?

- Do we know the target customers or target market?

- Have we estimated correctly the size of the target market?

- Have we covered the right-size market with the design? Have we tried to cover too broad a market? Have we designed features into the product or service that have no value to the target customers?

- Have we tested the basic concept or a model of the design with potential customers?

As we’ll see, Sol Price initially failed on one checkpoint. He overestimated the size of the market for his business. Once the designer knows the purpose of the design and its beneficiaries, he or she goes on to answer the second question.

Second Phase: How Do We Create the Best Design?

In this phase, the designer must decide what functions the design must perform to meet its purpose and what ideas, patterns, forms, and processes can be combined to provide the new functions and be practical for implementation.

Sol and Robert Price designed not only what functions their business would perform but also what it would not do. By selling only name brands that were advertised nationally, they could keep advertising costs low. They could trim the costs of receiving, stocking, and inventory by carrying only 3,000 brand-name products. A typical Kmart at that time carried 100,000 brand-name products. Sol said that he set the limit because “you can’t be everything to everybody.” This wisdom applies to designs of all products and services that have high costs of marketing, production, and distribution. (It does not apply to the Internet economy, where the costs of marketing, producing, and distribution may be so low that it may be economical to carry a million products or services, as do eBay and Amazon.)

The award-winning movie maker Sidney Lumet has directed more than 30 feature films, including Twelve Angry Men, Serpico, Murder on the Orient Express, The Verdict, The Pawnbroker, and Dog Day Afternoon. Lumet says his first phase begins with asking the screenwriter: “What is this story about? What did you see? What was your intention? Ideally, if we do this well, what do you hope the audience will feel, think, sense? In what mood do you want them to leave the theater?’” He says the answers to these questions determine how the movie will be cast; how it will look; how it will be made, edited, musically scored, mixed, and titled. For more, see Lumet’s book Making Movies (New York: Vintage Books, 1996).

The Prices also designed what functions the customer would perform. By having customers pay with cash or a check, they could eliminate credit card fees and accounts-receivable costs. By having customers buy goods in bulk packs, they could eliminate shipping-breakdown costs. By having customers pick up their own merchandise at their warehouse, they could eliminate delivery costs. By placing the warehouse in a low-rent area, they could keep overhead costs low.

In the second phase, most designers use new technology only when the new technology is proven and is needed to create the best design. Sol Price didn’t need new technologies, such as computer programs and automated warehouses, to make his initial design meet his purpose. Great designers first try forms or processes that fit existing technologies.

Developing new technology often takes large resources and long times. Saturn succeeded in designing a new car, a new factory, and new manufacturing processes; shaping a new workforce and management philosophy; developing new suppliers; creating a new distribution system; and fundamentally improving the way in which cars are sold. But it took seven years and it cost Saturn billions before it became profitable. Only a company like General Motors could have financed it.

When Honda moved to the United States, it duplicated a car, a process, and a factory it already had in Japan. It carefully selected a workforce and suppliers that it felt would readily adopt Japanese manufacturing methods. It sent workers to Japan to learn the process. It was up and running profitably in less than two years.

Many designers fail when they try to do too much in the second phase.

Optimize the Whole: Zoom In, Zoom Out

During the second phase, great designers optimize the whole. Frederick P. Brooks Jr., the chief designer of IBM’s 360, the most successful mainframe computer of all time, says that unity of design is the most important design consideration; see his book The Mythical Man Month (Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1975). To achieve unity of design, “the overall design must meet the intent or purpose of the opportunity” and “each part should be aligned and designed in best relationship to each other and to the purpose of the overall design.”

Master designers do not optimize the whole by optimizing the parts. They first optimize the whole and then they optimize the parts to fit the optimum whole. To do this, they begin at the highest level, then move rapidly from upper levels of the design to lower levels and back to upper levels. This ensures that the forms and functions of the smaller components of the design fit the overall design, and vice versa. For example, Edison

- could think one moment of providing power from a massive electrical distribution system

- could think the next moment of the design of the generator that would be needed to create the power

- and, a moment later, could think of a design detail in the rotor of the generator.

Master designers move up and down across the various levels of a design as often as 50 times an hour. This is called “zoom in, zoom out.” For more on this, see the article “A Field Study of the Software Design Process for Large Systems” by Bill Curtis, Herb Krasner, and Neil Iscoe, Communications of ACM (issued by the Association for Computing Machinery), November 1988.

Sol Price and Michelangelo could see the forest one moment, a small leaf on a single tree the next moment, and switch back to the forest in the next moment.

The third phase answers the question: “How do we ensure that the design will work?” It consists of experimental test, analysis, and redesign.

Third Phase: How Do We Ensure That the Design Will Work?

Sol and Robert rented an abandoned airplane hangar, put shelves in it, put a checkout counter at one end, and named it Price Club. They purchased name brand items in bulk. They had suppliers deliver them and put them on the shelves. They had shoppers load their own items off the shelves, bring them to the counter, pay cash, and carry them out. Robert Price came up with the idea of selling annual memberships for $25, causing the Wall Street analyst Michael Exstein to remark, “It was unimaginable, this idea that you could charge people to shop.”

As with many designers who venture into the unknown, their first test proved that their design didn’t work. In its first year, Price Club could not attract enough customers to be profitable, and it lost so much money that Sol was threatened with bankruptcy.

With time and money running out, Sol analyzed what was wrong with the design. He concluded that the design of the store, the product selection, and the cost structure were right. He admitted that his decision to sell only to retailers was killing the business. At bankruptcy’s door, the Prices changed the design. They opened the store to government employees and self-employed individuals. The chance to buy wholesale goods through their business and use them personally was irresistible to self-employed people, and Price Club was stampeded with applications. By 1981, sales had reached $230 million.

Within 10 years, the Prices had 25 stores generating $2.6 billion a year. Their design was so successful that Sam Walton copied it and called it Sam’s Club. Walton said, “I’ve stolen or borrowed as many ideas from Sol Price as from anybody else”; see the book Made in America by Sam Walton and John Huey (New York: Doubleday, 1992). Pace, Macro, and Costco also copied the design, and Price Club merged with Costco in 1994.

The second and third phases of the design process often are repeated until the design meets the purpose and is easier to implement. Occasionally, it may be necessary to return to the first phase and modify the original purpose, as Sol Price did.

General Principles of Experimental Testing

A general principle of experimental design and testing that great designers use is to identify the high-risk parts of the design and redesign to eliminate the risk early in the design process. Then test the new designs under the worst conditions and make corrections. The earlier in the design process that you test a design, the better—as shown in the sidebar on the IDEO Corporation.

Most great design organizations build models of the product as early as possible to test them. With that, and some of the other early-learning processes, they shortened their time to develop new products by 50 percent. That helps them keep their position as the new product leader in their market.

Master designers spend a great deal of time imagining what can go wrong with the design. Then they focus on the worst possible failures and design test processes and equipment that will stress the design in a way that induces the failures. They put early models of the design through the tests, and they find and fix the defects. They conduct reviews with potential investors—especially customers—to get feedback. The best designers eliminate almost all problems they discover in the test process before they finalize a design.

The IDEO Corporation leads the world in industrial design. Its designs range from high-tech blood analyzers to stand-up toothpaste tubes. Once it understands the market, the technology, and the constraints on the problem, IDEO observes people in real situations in that market, to find out what makes them tick—what confuses them, what they like, what they hate, and where they have latent needs not addressed by current products and services. IDEO’s designers visualize people using the product and then build a series of quick prototypes to evaluate the design in the hands of customers. The general manager, Tom Kelley, says the designers try not to get attached to the first few prototypes because they know they’ll change. For more on IDEO, see Kelley’s book The Art of Innovation (New York: Doubleday, 2001).

Because of the importance of “early test and build,” many organizations have completely redesigned the first processes in their product development cycles. For instance, the Powertrain Division of General Motors has developed very sophisticated computer-design programs that allow it to design engine components on the computer and then test them on the computer under simulated conditions. It also has developed new processes that allow it to build a first prototype of an engine part in hours, rather than weeks or months. Powertrain then measures and tests these rapidly made prototypes to correct any design defects before finalizing the design. As a result, the quality of GM’s engines has greatly improved over the past 10 years.

Find Opportunity First

It’s worth reemphasizing a point made earlier. The best designers first search for a great opportunity for success because identifying problems and solving them is low-leverage activity unless you know that those problems are the largest obstacles to your success; see Peter F. Drucker’s book Managing for Results (New York: Harper, 1964). Then the best designers focus only on problems that stand in the way of success.

Thinking Skills

Great designers use thinking skills—such as imagining, synthesizing, testing, and analyzing—in all phases of their design and problem-solving processes. Synthesis, or putting parts together to form a functional whole, is usually the most difficult thinking skill to learn. It’s one matter to analyze what makes an automobile work; it is far more difficult to synthesize hundreds of parts into a well-performing machine. Can the reader see where Sol and Robert Price used these thinking processes to find and seize a wholesale business opportunity? For more on thinking, see the sidebar.

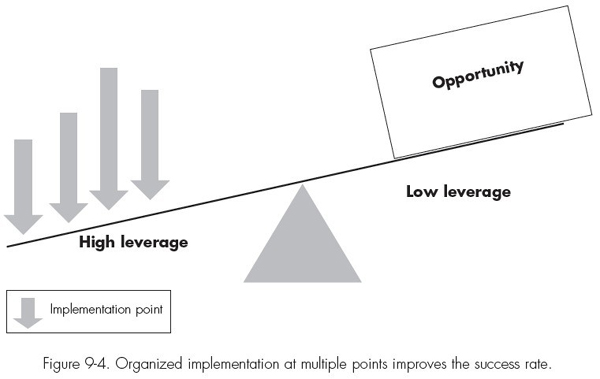

When the design work is completed, implementation begins. To achieve the full potential of the design, we should focus resources—such as people, money, and expertise—at high-leverage points. A high-leverage point is where we can spend a small amount of resources to produce large benefits. This is fully discussed in the next section.

Each of us can recall a moment in our life when a different decision or a different choice would have led to an entirely different future. So it was with Bill Gates in the summer of 1980.

Rapidly Seizing Opportunities at High-Leverage Points

In 1980, IBM decided to build a personal computer. It also decided that, to get it to the market fast with a competitive cost, it would have to be built with components and software obtained from outside IBM. Jack Sams was given the job of finding software suppliers. Sams knew that Microsoft, a small company with 32 employees, supplied most of the software for personal computers on the market. So he called Bill Gates, the president of Microsoft, and asked for a meeting. Gates said, “How about two weeks?” Sams said, “How about tomorrow?”

The next day, Sams flew to Bellevue, Washington. As he exited an elevator at Microsoft, he was met by what appeared to be an awkward, teenage office boy in a poorly fitting suit. The boy kept pushing his dirty, wire-rimmed glasses up on his nose. Sams soon discovered that this was Gates. Gates rocked back and forth during the meeting, appearing to be scatterbrained. Microsoft’s offices were tiny by IBM standards; they didn’t make a good first impression. IBM asked Gates to sign a nondisclosure agreement; Gates signed it without hesitation.

If someone wants to increase their thinking skills, we recommend the book The Teaching of Thinking, by Raymond S. Nickerson, David N. Perkins, and Edward E. Smith (Hillsdale, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1985). But, as we note in the main text, the highest-leverage way to learn anything is in pursuing a future opportunity. So work with a great opportunity finder if you can. Engage in a project requiring design and problem solving, and work with a good problem solver on the project.

In a three-hour meeting, Gates impressed Sams with his grasp of PC hardware, software, and the industry. Sams said that Gates was one of the smartest people he had ever met. Sams told Gates he wanted him to provide the disk operating system (DOS) for the new computer. Gates surprised Sams by saying he didn’t supply operating systems and referring him to DRI, which had a popular operating system at that time.

When IBM’s people visited DRI, the president was unavailable, and his business manager refused to sign the nondisclosure agreement, so under IBM’s rules of engagement, there could be no discussion. After hours of stalemate, the IBM representatives left.

Sams called Gates again and told him that Microsoft had to supply an operating system or IBM wouldn’t buy Microsoft’s language programs. Gates felt that operating systems were not his expertise and that developing an operating system would pull resources away from where Microsoft made its money. Besides, if Microsoft entered the operating-system business, DRI might react by entering the language business.

However, pressed with an ultimatum, Gates decided to do it. He knew another developer who had an operating system. A visit with the other developer confirmed that he would sell his operating system. Gates immediately called Sams to tell him he had it. They discussed whether Microsoft or IBM should buy it. It’s not clear whether either of them knew the significance of the ownership of that piece of software. It was decided that Microsoft would buy it, and that decision ultimately drove Microsoft’s stock value to $400 billion. For Gates and Sams, this was a defining moment, a high-leverage point in time.

Sams believed that, if IBM bought the software, the company would bungle it. He wanted Microsoft to be responsible for integrating all the software. Gates wanted to be known as the company that supplied IBM’s personal computer software. He knew that was a high-leverage opportunity and that the purchase of the operating system was a high-leverage point, so he bought the software for $50,000—a lot of money at that time.

Referring to this leverage point, the writer-analyst Paul Carrol said, “Sams may be right that IBM would have bungled DOS, but IBM, in not being able to seize that chance, put themselves at a horrible disadvantage.” In defense of Sams, leverage points are fleeting; you have to act quickly, and if he had brought DOS inside IBM, that probably would have delayed IBM’s introduction of the PC by at least a year.

There would be other high-leverage points on Microsoft’s journey and, nearly every time, Gates took the right action at the right moment. Later, Gates sold nonexclusive rights to IBM to use the MS-DOS software. IBM was confident that the software was useless without a special chip it had designed into the computer. Later, Compaq Computer reverse-engineered the IBM chip and produced an IBM clone. As others developed clones, Microsoft sold them the MS-DOS software, which eventually became the basis for Windows, now the standard software on most of the world’s personal computers.

Later, IBM spent hundreds of millions of dollars suing Compaq and Microsoft, trying to reclaim the MS-DOS software that Microsoft had bought. IBM lost nearly every suit. At the time of the leverage point, Microsoft had 32 employees and a few million dollars in sales, and IBM had 340,000 employees and $26 billion in sales. But Microsoft had the inside expertise and was led by Gates, a master of high-leverage opportunity and high-leverage points.

This is also an example of a power insider hiring an expert insider. The irony is that IBM got the expertise but Gates got the power. Another example of seizing at high leverage points took place at one of the premier golf equipment manufacturers.

Long before PING Inc., was known for its excellence in designing and manufacturing golf equipment, its founder, Karsten Solheim, was working for General Electric in 1953 and playing golf with a borrowed set of clubs. He was frustrated with the difficulty of putting straight. But he used his mechanical engineering background along with an observation on the construction of tennis rackets. He reasoned that if tennis rackets were weighted around the perimeter of the head of the racket, the same concept could be used to design a putter. As soon as he knew that he had an invention that improved putting accuracy, he acquired a loan for machining equipment and set up operations in his garage.

Karsten Solheim grew his enterprise to 2,000 employees, with Forbes estimating his net worth at $400 million; see Karsten’s Way by Tracy Sumner (Chicago: Northfield Publishing, 2000). Nevertheless, in the mid-1990s, modern market pressures increased the demand for more variety, newer technology, higher performance, and continually evolving design appeal, placing the entire corporation in an uncomfortable position. PING was faced with high overhead and slipping sales. The task ahead was formidable for the executive team members. They found themselves in a position where maintaining the legacy of years past would no longer suffice. They would need to face the daunting task of reinventing something that had worked flawlessly for decades.

John A. Solheim, one of Karsten’s three sons, was promoted to CEO of PING in 1995, and he began the process of creating a leaner, more efficient corporation. He focused PING’s business by eliminating activities that were not directly supporting the manufacture of golf equipment or didn’t support corporate values. He also restructured the existing departments and leveraged the fitting system that PING is famous for. In 2001, he had only one major department that was still in need of transformation, the engineering department. He appointed his son, John K. Solheim, as vice president of engineering to tackle this task (figure 9-1).

The PING engineering department was in need of improvements relating to the speed of time to market and rate of innovation and productivity. Taking a design concept to production in two years was the state of the art in the 1980s; but in 2001, the design could be obsolete before the first piece came off the production line. Also, launching a single line of products every other year would no longer compete with the faster moving competitors. PING needed to launch products four times faster than before. It would also need to attempt the unnerving task of updating a look of a product that has been branded with a distinctive and differentiated look. The speed of innovation and the product complexity would also need to increase substantially if PING was to regain its market dominance in premium fitted clubs.

John K. Solheim quickly began to get the right people using the right tools with the most efficient processes and procedures. He hired talented people to lead teams and reorganized the existing PING engineering department structure. He also purchased productivity tools such as Pro/Engineer to improve computer-aided design productivity and launched lean initiatives to improve processes. He then arranged the design teams into a flat structure that had leadership but deemphasized hierarchy and allowed all the company’s designers to sell their ideas to management with an unprecedented ability to manage their idea from design through production.

The final improvements decreased their design concept to production time from 24 to 9 months and increased the number of products introduced each year from 3 to 14 while maintaining the same staffing levels. During this same period, PING launched the number one driver, the number one iron, and the number two putter brands. When asked about the changes that PING has been through, John K. Solheim explains: “Looking back at all the improvements we’ve made, I credit our success to having the right people, providing them with the right tools, and creating efficient processes.” Leaders always put the right people in the right high-leverage places so that they can seize opportunity quickly.

To learn how to find and seize opportunities using high-leverage points, the leader must answer these questions:

- What is a high-leverage point?

- How do we find high-leverage points?

- How do we act at multiple points in an organized campaign?

What Is a High-Leverage Point?

A high-leverage point in a system is where a small action produces a large change in operation and output. There are many varieties of high-leverage points, from the up button in an elevator to a bottleneck in a manufacturing process. Learning to find high-leverage points is both a science and an art.

An Indianapolis 500 race car has small wings on each side at the front. The Indy winner Bobby Rahal says that changing the angle on the left-front aerodynamic wing by one-tenth of one degree might get you around the Speedway one-tenth of a second faster. At the end of 200 laps at Indianapolis, that’s a difference of 20 seconds, which is enough to win or lose the race. Rahal says that if you can figure out enough of these minute adjustments so that you can gain a few seconds per lap, you can run away with the Indy 500. The angle of each wing is a high-leverage point because a very small change in the angle makes a large difference in the outcome of the race.

How Do We Find High-Leverage Points?

To repeat, a high-leverage point is where spending a small amount of resources produces large benefits. Peter Senge, who has researched the dynamics of systems, says that “the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious.” For example, a very large force is needed to change the direction of a moving ship, if you are pushing its front in the direction in which you want it to go. But a small force to change the angle of the rudder will turn the ship. The rudder is an example of an obvious leverage point. However, the tiny trim tab on a boat is a not-so-obvious leverage point. An even smaller change in the position of the trim tab increases or decreases how much effort it will take to move the rudder.

Because of the great value of high-leverage points, it’s very important to learn how to find them. Let’s look at several examples.

Edison, Master of Leverage Points

In the movie Edison the Man, Spencer Tracy, playing Edison, is sitting at his desk early one morning, after struggling through the night trying to find a suitable filament. He is holding a piece of sewing thread in his hand. “We’re going to use carbon,” he says to the men just coming to work. After he gives instructions to one of the men about how to impregnate the thread with carbon and bake it, the man says, “It’s too delicate, Tom, I’m afraid we’ll break it.” “Try it anyway,” Edison says. Another man says, “But we’ve tried carbon before.” “Not carbonized thread,” Edison says. “That isn’t very scientific,” the man says. “I told you we had to leave science behind. Now come on,” Tom says, motioning for them to get on with it.

They prepare the thread as Edison has instructed and, lo and behold, though all previous filaments had burned out in minutes, the lamp burns continually through that night and the following night. In that dramatic moment, Edison gives the world the gift of electric lighting.

This story reinforces the myth that breakthroughs come magically. As we’ve said above, we’ve been led to believe that if we simply free the imaginative and playful children’s minds within us, we will be able to create visions.

But on the contrary, before Edison devised the first filaments for his lamp, his physicist, Francis Upton, already had determined that the filament must have an electrical resistance of about 100 ohms, have a melting point over 6,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and be extremely thin and long without being too fragile. The eventual focus on carbon was no accident, in that Edison knew its properties and had worked with it in developing an improved telephone voice-piece. But even after his team narrowed the search to extremely thin carbon filaments, the search lasted for the best part of 1879.

Edison and his team mentally “saw” their solutions long before they ever realized them in the laboratory. This narrowed the scope from millions of experiments to thousands. In other words, they knew millions of things that wouldn’t work, so they didn’t need to try them. Long before the “magical” experiment took place, they knew which materials and experiments would have the highest leverage.

The highest-leverage opportunity for Edison was creating a commercial electrical lighting system. To accomplish this, he knew that he would have to develop all the parts of the generators, lamps, and distribution system. Of these developments, he knew that finding a suitable lamp was the high-leverage development and that the major problem would be inventing a high-resistance, high-temperature, yet durable filament. Finally, he knew that the highest-leverage action was to design, build, and mount the filaments and create vacuums around them (figure 9-2).

Realizing the importance of the highest-leverage action, Edison invented a self-contained, fast-turnaround laboratory to do it. He staffed it with

- chemists who could carbonize his filaments

- physicists who could calculate from the properties of materials whether they had a chance of working

- an expert on high vacuum

- a glass blower

- an expert on glass-to-metal seals.

This team could start with an idea for a filament in the morning, build it that afternoon, and test it that evening. The scientists were able to test thousands of materials, filament cross-sections, carbonizing techniques, dozens of vacuum methods and glass-to-metal seals, and hundreds of wire supports for the filaments.

Two years after he started his lighting project, Edison ran out of money just as they found the answer. If he hadn’t searched for the highest leverage in the beginning, he never would have made it. Rather than 2 years, it would have taken 10 years to develop a suitable filament.

The search for high-leverage points begins once you have a vision of a great opportunity. Starting at the highest level of the opportunity, you systematically work your way down, level by level, selecting the highest-leverage points at each level. Then, to make sure you have identified a genuine high-leverage point, you need to ask whether a small change at that point will make a large difference in your ability to seize the high-level opportunity. Edison knew that if his team could invent a suitable filament, he could create a commercially successful electric lighting system. You need to understand the leverage point well enough to perform the right action on it.

Churchill also was a master of leverage-point decisions, especially in crisis. Two of his most important decisions at leverage points took place shortly after he became the prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Crisis Leverage Points and Winston Churchill

The first decision came just as Hitler’s armored divisions invaded France. The French begged Churchill for British fighter planes to help in their defense. Churchill believed that the French would lose, even with British fighter support, and that the planes would be needed to defend Britain. He said “no.” In other words, he decided that it would be a low-leverage action. He was proved right when Hitler began his air attack on Britain. Without the planes, Britain wouldn’t have withstood Hitler’s massive bombing attack.

A second, difficult, leverage-point decision was necessary when France surrendered to Germany. Churchill did not want the French Navy to fall into German hands, so he asked the French admiral to either join the British Navy or demobilize his ships. When the admiral refused, the British Navy seized all French ships in British waters and sank or disabled all the other French ships it could find. Churchill recognized this as a high-leverage point because the Germans would reap a large benefit from the French ships, and only a small amount of British resources was required to seize or sink them.

Leverage Points of Expertise

John Browne, the CEO of BP (formerly British Petroleum), insists that “everyone in the company who is not directly accountable for a profit be involved in creating and distributing knowledge that the company can use to make a profit.” He says, “The key to reaping a big return is to leverage knowledge by sharing it throughout the company so each unit is not learning in isolation.”

To expand on Browne’s idea, consider expertise as a valuable resource. Then consider that, when learning takes place in one part of an organization, a great deal of the investment to learn already has been made. A leverage point of expertise is any place in an organization where known expertise can be applied to get large benefits.

Leverage Points in Time

It is common practice to shorten the time it takes to finish a project by having planners find the path in the project that takes the longest time and then work to reduce the time on that path (often called critical path planning). These critical paths that are projected to hold up the entire project should be treated like the time when the chest cavity is open during open-heart surgery and blood is being bypassed around the heart—that is, holdups should be minimized as much as possible. You may ask what would be an acceptable reason to interrupt the surgeon during this time: taking a nonemergency call from his daughter or his stockbroker, or from a racquetball buddy who wants to arrange a match?

When a major portion of the project is held up until an action is finished, we should use the rules for the surgeon when the chest cavity is open.

Edison, Gates, and Smith worked all night with the person at the high-leverage point. When Curie knew she was onto something, she worked nonstop. Of course, any good concept can be carried too far. However, in this fast-paced world, we teach the open-heart-surgery principle and many other models and concepts to companies that want to reduce product development time and time to market.

Leverage Points in Battle

In 1940, the freedom of the world was threatened as Hitler rolled his war machine across Europe. He seemed unstoppable. On December 7, 1943, U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt flew to Tunis, where he was whisked from his plane and placed in General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s car. As the car drove off, he turned to Eisenhower and said, “Ike, you’re going to command Overlord.” Operation Overlord was the code name for the Invasion of Normandy—history’s greatest sea-to-land battle.

Throughout his life, Eisenhower was chosen to lead important missions. Why? Because he had a high batting average of successful missions. He was not only well-prepared for opportunity; he almost always delivered great returns to investors in the mission. He delivered because his thinking was both high leverage and high meaning.

His high-leverage thinking can be seen in the way in which the invasion was planned. He knew that attacks from sea to land are inherently difficult and generally unsuccessful. Although he had commanded successful, large-scale sea-to-land operations in North Africa, Sicily, and Salerno, these were not direct frontal attacks from the sea against highly fortified land positions. So he knew he had to find high-leverage points.

The Germans had constructed a seemingly impenetrable wall of fortified gun bunkers along the French coast. The shores were heavily mined. On the other side of the wall were 20 divisions of battle-hardened, heavily armed, highly mobile Panzers under the command of the legendary Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. The Germans could launch a massive counterattack with over 100,000 troops within days of the first attack. Behind all that were 600,000 heavily armed German troops, allocated to defend France.

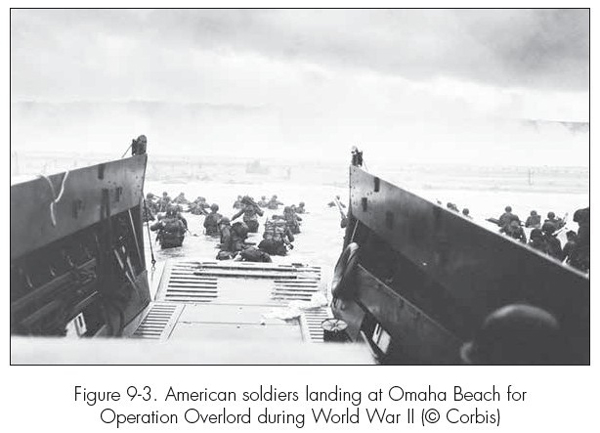

Eisenhower knew that, to win over superior forces, he had to concentrate his forces, act with speed, be mobile, and surprise the enemy. Because the Germans had to defend over 3,500 miles of coastline, running from Holland to the southern end of the Bay of Biscay, they had to spread out their forces. In contrast, the Allies could concentrate their forces on a small part of the coastline and surprise the Germans. The Allies chose five beaches on the Normandy coast as high-leverage points (figure 9-3).

Because most high-leverage points exist only in narrow windows of time, they must be seized quickly. Eisenhower knew that the invading troops would be outnumbered six to one if Rommel were able to move his full force toward Normandy. Eisenhower decided to decrease the mobility and speed of Rommel’s divisions by bombing all the railroads and bridges behind Rommel’s forces. This would isolate them from their supply lines. Ike also decided that the Allies would bomb Rommel’s tanks if he moved them forward. These were high-leverage-point bombings:

SINCE THE FOCUS OF EFFORT REPRESENTS OUR BID FOR VICTORY, WE MUST DIRECT IT AT THAT OBJECT WHICH WILL CAUSE THE MOST DECISIVE DAMAGE TO THE ENEMY AND WHICH HOLDS THE BEST OPPORTUNITY OF SUCCESS. . . . IT FORCES US TO CONCENTRATE DECISIVE COMBAT POWER JUST AS IT FORCES US TO ACCEPT RISK. THUS, WE FOCUS OUR EFFORT AGAINST CRITICAL ENEMY VULNERABILITY, EXERCISING STRICT ECONOMY ELSEWHERE. (FROM WARFIGHTING: THE U.S. MARINE CORPS BOOK OF STRATEGY)

However, the air forces were not under Eisenhower’s command. The generals who headed the air forces believed that strategic bombing of German industry and terror bombing of German cities would end the war, and that Operation Overlord was not necessary. Eisenhower believed that these views were dangerous nonsense—that a fanatical, resolved Hitler would fight to the death and would have to be defeated on the ground. Hitler proved Eisenhower right.

Convinced that bombing before and during the invasion was essential and high leverage, Eisenhower gambled his career on it. In London, he told the combined chiefs of staff, “Every obstacle must be overcome, every inconvenience suffered, and every risk run to ensure that our blow is decisive. We cannot afford to fail.” He threatened to step down from the position of commander-in-chief if he weren’t given the support of the air commands. He got his air support, and later it would be clear to everyone, including the objecting air commanders, that he was right. He had seen what others hadn’t seen and was willing to stake his career on it.

How Do We Act at Multiple Points in an Organized Campaign?

When the great achievers found high-leverage points, they organized teams and designed action plans to act on all the points available, in a timely, coordinated way. Eisenhower and his staff divided the overall mission into smaller, coordinated missions that were focused on high-leverage points. The records of his battles include an example of the overall Overlord mission and a small, coordinated mission at a high-leverage point:

MISSION OF ENTIRE ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCE BEFORE THE INVASION OF NORMANDY: YOU WILL ENTER THE CONTINENT OF EUROPE AND, IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE OTHER UNITED NATIONS, UNDERTAKE OPERATIONS AIMED AT THE HEART OF GERMANY AND THE DESTRUCTION OF HER ARMED FORCES. AFTER ADEQUATE CHANNEL PORTS HAVE BEEN SECURED, SECURE AN AREA THAT WILL FACILITATE BOTH GROUND AND AIR OPERATIONS AGAINST THE ENEMY.

HIGH-LEVERAGE-POINT MISSION ASSIGNED TO ENGLAND’S SIXTH AIRBORNE DIVISION OF PARATROOPERS DURING THE INVASION: LAND ON THE EASTERN END OF THE BEACHHEAD NEAR CAEN. ONCE THERE, CARRY OUT THE FOLLOWING TASKS: SECURE CROSSINGS OVER THE ORNE RIVER AND CAEN CANAL, KNOCK OUT BIG COASTAL GUNS IN THE AREA, AND BLOCK GERMAN REINFORCEMENTS FROM REACHING THE ALLIED TROOPS LANDING ON THE BEACHES.

All the high-leverage points were acted on in a well-timed, well-executed invasion. In the early hours of the invasion, Special Forces were dropped behind the enemy’s lines to direct massive naval guns that would pound the German fortifications just before the first troops landed. Commando teams were dropped in by gliders and by parachute to blow up key bridges and secure important positions. Thousands of individual missions at high-leverage points were planned and timed to support the main thrust, the landing at five beaches on the Normandy coast.

Acting at many high-leverage points in an organized, timely way increases the probability that you will achieve large returns, even if action at one of the high-leverage points fails or if you have high, unexpected losses, such as those the American forces suffered at Omaha Beach, a code name for one of the beaches. Figure 9-4 shows how this increases your chances of success.

There are possibilities that you could become blocked at a critical leverage point. You should have backup plans for the critical points. Risk is reduced by planning well, by assessing risks at critical points, by taking preemptive action if possible, and by focusing at high-leverage points. When you put small amounts of resources at multiple high-leverage points, you minimize losses if one doesn’t pay off.

High-Meaning Thinking at High-Leverage Points

From his past combat leadership, Eisenhower knew that the success of the invasion of Normandy depended heavily on the front wave of soldiers. If the soldiers came storming out of the landing crafts and attacked the enemy, the invasion would succeed. If they cowered behind the landing crafts, the invasion would fail.

So Eisenhower spent his evenings and weekends with soldiers that were part of the first assaults. He said that every soldier who risks his life should know why, and he should see, face to face, the man who was leading him into battle.

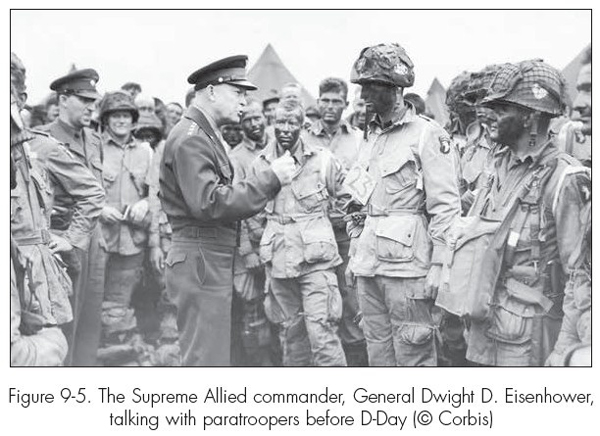

In the four months before D-Day, Ike visited 26 divisions, 24 airfields, 5 ships, and countless depots, shops, and hospitals. He gave a short speech at each site about defending the future freedom of all people. He said that the men were fighting for their loved ones back home and for the lives they would return to when the war was over. Then he made the rounds, shaking hands and asking questions (figure 9-5).

Whereas other generals asked the men about their military specialties, training, units, or weapons, Eisenhower asked them, “Where are you from?” “What did you do back home?” “What are your plans for when the war is over?” “Who’s waiting back home for you?” To other generals, these were soldiers. To Eisenhower, they were citizen-soldiers, caught up in a war that none of them wanted. He knew that what meant the most to them were those they had left behind.

Stories of his inspiring conversations with the men quickly spread through the camps after he left. The troops knew that Eisenhower saw the war through their eyes and knew what really had meaning for them. The soldiers in the Normandy invasion fought valiantly. The invasion was so successful that Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, who seldom praised anyone or anything, said, “The history of war does not know of an undertaking comparable to it for breadth of conception, grandeur of scale, and mastery of execution.”

Questions on High-Leverage Planning and Last Thoughts

To ensure that you have a high-leverage action plan to seize an opportunity, you may ask yourself these kinds of questions:

- Is the plan organized in high-leverage thrusts? Does each thrust have the optimum resources?

- Are the critical high-leverage points identified along with their risks? Have backup or contingency plans been developed?

- Do we have the resources to carry it out? Have we planned and committed resources at the high-leverage points?

- Is there a detailed plan that specifies actions, resource applications, timing, assignment of responsibilities, and measures of success? Has each person with a stake in the opportunity accepted responsibility for his or her assigned actions?

- Are events scheduled to minimize total implementation time and total resource consumption, while maximizing the final outcome?

One last thought on seizing opportunity: If a great opportunity or threat exists, it’s only a matter of time before other great achievers will find it and seize it. If we don’t prepare for, find, and seize the great opportunities that come our way, we suffer the costs of lost opportunities and the loss of potential return on our time, ideas, energy, and resources.

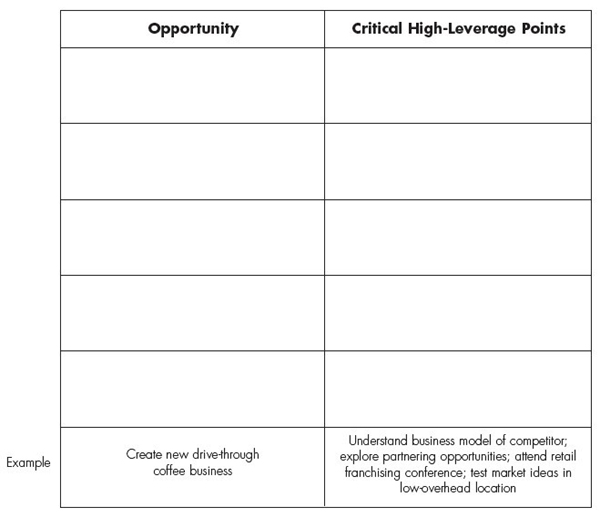

Self-Evaluation Exercise

Self-Evaluation Exercise

List opportunities from earlier exercises and/or identify opportunities from other areas of your life. Place these in the left-hand column below. Then, for each opportunity, list critical high-leverage points for implementation in the right-hand column.