In the previous module, you learned how the Internet is transforming the way in which business is done. As information becomes pervasive, markets become global, and integration becomes key to business success and even survival.

The problem, of course, is in the doing. During the dot-com, many businesses thought that they had the magic bullet when it came to effective use of information technology (IT). Of those, many failed because they could not develop an effective strategy for deploying IT in support of business. Many others survived bad technology starts, but because the experience was so painful, they ended up retrenching and reverting to older, more manual processes. These are the businesses that are having problems today.

Business today is moving to a virtual business model, where technology takes the place of capital infrastructure. These networked virtual organizations (NVO) are developing sound approaches to the application of technology to enable business. More importantly, because of the free flow of information enabled by the Internet, you can see exactly how they do this.

This section examines these NVOs and discusses how they are transforming the conduct of business, government, and industries. It does this with an eye toward capturing their strategies so that you can use them to transform your approach to business.

By the end of this module, you should be able to do the following:

Explain key management strategies.

Describe Internet-enabled business strategies and how IT adds value.

Describe the Business Value Framework of an organization.

List the three components of the Business Value Framework.

Explain the three strategies for NVOs.

This section reviews several fundamental management strategies and explores the impact of the Internet and IT on each. You will learn each of these concepts:

The point of business is to deliver a good or service to a consumer and capture some of that perceived value in the form of revenues. The higher the value perception, the more revenues that can be generated. Perceived value is generally a problem for industries in which the product has become a commodity.

For example, take the case of tissue, which is very commoditized. For most brands, the price charged is very nearly the cost of manufacturing the product. Yet, some players in the market are able to charge a premium for their tissue, which consumers are willing to pay. They are able to charge extra by differentiating the product in some manner. For example, some put the tissues in designer boxes, add scents, or make the tissues look prettier with embossing. Consumers view these small changes to what is a commodity product as being intrinsically better, so they are willing to pay more.

But what is this idea of value in the context of general business? How can it be measured and, more importantly, how can it be increased? This section examines the concept of value in business. It looks at value chains and how they can be optimized. It also seeks ways to add value without adding business resources by using out-tasking and outsourcing to augment business personnel and leverage the core competencies of others.

Value is a perception of worth. If a consumer believes that the worth of a product is equivalent to the worth of the money that would be spent to purchase the product, the value of the product is the same as its price. Another way to look at this is that the customer believes that the utility of the product is equivalent to its price.

In practice, though, utility is not the only criterion that determines a value perception. As noted, the perception of value can be based on many things that do not actually add to the utility of the product.

Many times, however, value can be augmented when a vendor packages a product with other related products or services. This is why many IT vendors are now pursuing managed services. The product that is being managed is a commodity for which the market has determined that the price must be close to the cost to produce it. The price of service, on the other hand, is strictly driven by the customer perception of value. Thus, margins can be kept high, and the vendor can leverage the commodity to generate revenues in excess of what the commodity itself would drive.

Successful organizations must maximize the value perception of the customer to generate the highest possible revenues from the goods or services they offer. Organizations have two primary objectives:

Create value for the customer: This means creating something that the customer will value enough to want to buy. For example, this entails producing a product that is useful, relevant, and affordable for the customer.

Capture value for the owner or shareholder: This means making a profit by selling something for more than it costs to make it.

Organizations make a profit when their revenues are greater than their costs:

Revenue: The amount that buyers are willing to pay for a particular good or service

Cost: How much an organization must pay to create that particular good or service

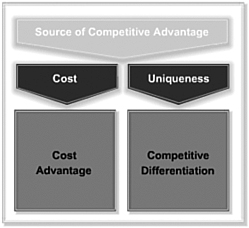

Two common strategies are used to increase profits:

Maximize revenue (growth): This can occur when an organization is the sole or main supplier of a product or service and demand is increasing. Another way to grow your revenues is through competitive differentiation: When an organization offers unique benefits, such as better quality products or faster services, customers prefer its products or services over the competition.

Minimize costs (productivity and efficiency): This occurs when an organization reduces the costs of its products or services, creating a cost advantage. Organizations can reduce their operating costs by finding less expensive source materials, by improving their manufacturing processes, and by using centralized business processes and automation.

As you can see in Figure 2-1, a business seeks a balance between cost containment and revenue generation. These dynamics are not independent. Reducing costs too much might impede the ability of a business to generate revenue, whereas completely fixating on revenue generation might allow costs to spiral out of hand. It is only when maximum revenue is generated at maximum efficiency—for example, at the lowest cost—that a business can survive and expand.

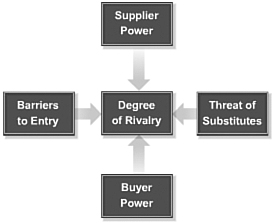

Michael Porter, the founder of the Monitor Group and a world-renowned expert on management, in 1985 developed a framework for thinking about how cost containment and revenue generation work in the marketplace. His five forces allow you to evaluate how successful a given business will be in a particular market. The five forces are buyer power, supplier power, barriers to entry, asset specificity, and the threat of substitute products.

Following is the framework for the five forces so that you can apply it to maximizing revenue and minimizing costs:

Buyer power: This is the power that buyers have over the producers in an industry. For example, if there are numerous cell phone manufacturers but a limited number of people buying them, the buyers have more control, and prices will drop.

Supplier power: If suppliers are powerful, they can exert control over the producers that they supply. For example, if only one mine provides a needed material to a particular industry, that mine can sell its material at a high price.

Barriers to entry: In theory, any organization should be able to enter or exit a market. In reality, however, many different factors can prevent a new organization from entering an existing market. These can be such things as government regulations, patents or proprietary knowledge, or asset specificity.

Threat of substitute products: This occurs when a product has competition from a different industry. For example, the price of containers from other industries, such as glass bottles, steel cans, and plastic containers, affects the price of aluminum beverage cans.

Rivalry among firms in the industry: How much rivalry and competition exist between different organizations within the industry? This could be low if there is an informal code of conduct or high if there are numerous organizations competing for few buyers.

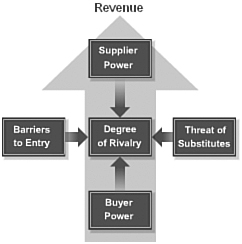

Figure 2-2 depicts the Porter Five Forces Framework. Armed with this framework, you can now examine how different business strategies work in practice. For example, competitive differentiation can be successful because, as a strategy, it can reduce buyer power as a result of the unique product being produced. A unique product reduces buyer sensitivity to price.

Competitive differentiation also addresses supplier power. With higher sales margins, you can either absorb supplier price increases or pass along those increases to the buyer, because there are no buyer alternatives.

Finally, competitive differentiation allows you to fend off new entrants to the market because you have already defined the product and have set standards for utility and price that the new entrant must beat. Figure 2-3 illustrates how a firm can leverage different market forces to generate revenue.

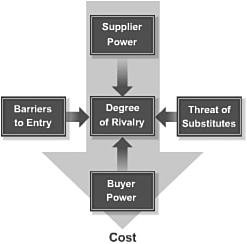

A second strategy that has been discussed is that of cost advantage. Figure 2-4 shows how a firm can leverage market forces to achieve a competitive cost advantage. If you are producing a good or service for the lowest cost, reducing the sale price negates buyer power by driving competitors out of the market, thus leaving the buyers with only you as a provider.

Cost advantages also give you some advantage over raw material suppliers because, to maintain a cost advantage, you are probably making large supply purchases at the lowest possible cost. Suppliers who want to be part of your market are forced to compete with each other for your business.

Cost advantages also discourage new entrants. If your cost is truly the lowest possible manufacturing cost, new entrants are less likely to target your market in the first place; however, if they do, they need to find a way to beat your cost advantage.

Value, then, is a dynamic that seeks to increase the willingness of the buyer to buy at the price the seller wants to sell. When the value perception is high, the buyer will pay the asking price. As noted, though, sometimes the buyer will pay the price asked when no alternative products or services are available in the market. In a situation such as this, value perception is lower than the price, and the buyer will switch to a lower-cost provider when one presents itself.

Armed with a definition for value, you can learn how that value is generated by the business and delivered to the buyer. This generation and delivery of value is called a value chain. This section explores some of the implications of such a chain.

Michael Porter, in addition to his five forces, developed a flow diagram that illustrates the sequence of activities that generates value. As shown in Figure 2-5, these activities are inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service and support. You will learn about each of these steps next.

Inbound logistics refers to the process of receiving, storing, and distributing raw materials for the manufacturing process. In many businesses, this step is highly automated and involves delivering raw materials to the production process in a just-in-time manner.

Operations refer to the process of turning raw materials into finished goods and services. This includes any manufacturing process. In businesses that are tightly integrated with OEM manufacturing, this might be a wholly or partially outsourced activity. However, even completely outsourced production operations need internal management of the operations process.

Outbound logistics is involved in the warehousing and distribution of finished goods. This process, too, can be almost wholly eliminated if a business is tightly coupled with its customers. For example, many vendors expect their customers to warehouse and distribute their products.

Marketing and sales is composed of the activities that identify customer needs and generate sales. Although this process is shown as a downstream activity to outbound logistics, in reality it can take place along the entire value chain. Successful businesses usually attempt to identify customer needs well before anything is actually manufactured and often involve customers in the process of overseeing manufacturing.

Service and support refers to the activities of ensuring that the goods delivered to the customer continue to perform as expected and to deal with any customer difficulties arising from the use of the product. In addition, as noted previously, service can be the point of the value chain, where the primary focus of the business is in the delivery of service offerings.

All these value chain processes depend on support functions within the organization, such as management, human relations, technology associated with creating value activities, and procurement activities such as purchasing.

As has been noted, the entire value chain can be highly leveraged by technology. Technology can be applied at each activity along the value chain to drastically impact the degree of effectiveness of that activity. Changes in technology can dramatically affect the competitive advantage of your organization. Changes in technology can incrementally change the value-adding activities themselves or can create new configurations in the value chain.

For example, implementing advanced information systems and standardizing the network infrastructure can make an organization more competitive. They can reduce cycle times, allow faster decision making, and create higher levels of integration with partners and customers. This results in lower cost and higher levels of satisfaction throughout the value chain.

The application of Internet-enabled IT can confer significant competitive advantage. The Internet-centric organization gains competitive advantage and increases its market value not only through the products and services it sells, but also through the way in which it shares and uses information.

Value chains link the supply chain in your organization with the customer. Implementing Internet-enabled systems in different parts of the value chain reduces costs, increases the efficiency and productivity of your organization, and creates new products and services for your customers.

The Internet and IT can support the value chain of an organization in several areas:

Primary value chain activities:

Inbound logistics: Automated storage, scheduling of incoming shipments, shipment tracking

Operations: Production scheduling, testing and quality assurance (QA), inventory management

Outbound logistics: Scheduling, shipping out products, routing, tracking

Marketing and sales: Pricing, availability and order management, product demonstrations, promotions, training

Service and support: Checking order status, maintaining pricing history, scheduling service and support, tracking problems, offering self-service programs to customers

Value chain support functions:

Organization infrastructure: Records management, scheduling, decision management support, compensation

Human resource management: Benefits enrollment, workforce resource planning, performance management, recruiting

Technology development: Collaborative design, computer-aided design, security, capacity planning

Procurement: Bidding, ordering and tracking systems, price analysis

It is no wonder that organizations enabled by technology can significantly outperform those competitors that are not technology enabled. What is even more important is that information technology is such a competitive advantage that even small businesses that are IT enabled can now outperform much larger organizations. IT, it turns out, can neutralize advantages that used to be defined by capital holdings. This is important in a global economy, where the ability to maneuver quickly can be a key to success. A large organization usually is not as responsive to market changes as a small company, and when the small company is empowered with the appropriate technology, the large company can be at a significant disadvantage.

On this and the following page, list all the areas in your organization where IT could affect your delivery of value or add competitive advantage.

___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ |

As you saw earlier, organizations strive to deliver value to the customer that is greater than the cost of the activities that created it, generating a profit. By analyzing the value chain of your organization, you can discover its core competencies, areas in which IT can improve business processes, and activities in which it can pursue a competitive advantage.

It is important to take a closer look at how cost advantage and competitive differentiation strategies apply to the value chain and how they can help your organization expand in the marketplace. Figure 2-6 shows how cost advantages and competitive differentiation, when applied to the value chain, can drive competitive advantage for a firm.

Cost advantage (productivity and efficiency): Cost advantage is achieved through the reduction of costs (for example, manufacturing or shipping) associated with bringing a product or service to the buyer and creating more revenue with the same amount of input (cost).

After your organization has determined the nature of its value chain for a given product or service, you can perform a cost analysis on each part of the chain. An organization develops a cost advantage by reconfiguring the links in its value chain to reduce the costs of as many stages as possible.

Reconfiguration means making structural changes, such as adding new production processes, giving business functions to external partners or organizations, changing distribution channels, or trying a different sales approach. Reconfiguration, though, does not necessarily come without its own cost. However, where such reengineering can be done within a predictable cost and time frame and provide a market advantage, it might be worth considering.

Competitive differentiation (growth): Differentiation stems from uniqueness and perceived value (how much customers think a product is worth). When an organization focuses on activities it does best and creates innovative and unique products and services, it naturally rises above its competitors. As its products become more valued in the marketplace, an organization can increase the price of those products, creating revenue growth. An organization can achieve a differentiation advantage by either changing individual value chain activities to increase uniqueness in the final product or by reconfiguring the entire value chain.

This approach, too, is not without its risks. Differentiation for the sake of differentiation is easy, but the customer might not appreciate or value it. It is critical that as you innovate, you do so with attention to what will resonate with the customer. Many companies have devoted a large portion of their budget to R&D activities only to find that the market was not ready or was unwilling to buy the fruits of their innovative activities.

In the previous section, you discovered that it is possible to manipulate the value chain to achieve cost reduction and competitive differentiation. One of the most effective ways to do this is to apply IT to the various value chain steps to increase the flexibility and cost dynamics of the business.

Another way in which Internet-enabled IT allows a business to reduce cost and differentiate is to provide a means to share or even off-load pieces of the value chain to other organizations. When only pieces of the step are off-loaded, this is called out-tasking. It is called outsourcing when the complete step of the value chain is done by another organization.

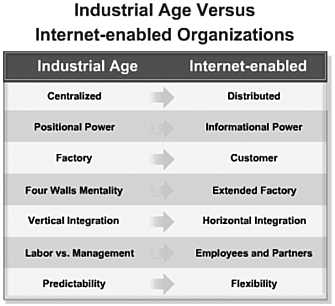

For those doing business in the twenty-first century, the whole notion of outsourcing might seem pretty mundane, but it is actually a radically new way of looking at business. In the Industrial Age, manufacturers concentrated their operations in a centralized physical location. This allowed them to own and control their entire value chain, which gave them an advantage over the competition. Internet-enabled organizations are different. They connect with customers, employees, partners, and suppliers in ways not previously possible. Using the Internet, it is possible to share knowledge and key processes globally in near real time. Figure 2-7 shows the stark differences between an Industrial Age firm’s value chain compared to an Internet-enabled firm’s value chain.

This information exchange allows a tighter coupling between disparate organizations than was ever possible even between departments within the same organization during the Industrial Age. This is important because it allows different organizations to focus on their core competencies and leverage others to create more value than would be possible if a business tried to achieve competency across all the value chain functions by itself.

For example, a clothing manufacturer might sew clothes extremely quickly and efficiently but not know anything about how to prepare the material beforehand or how to sell the finished product. Another organization might know a lot about how to market clothes but know relatively little about how to manufacture them. When these two organizations work together, the clothing market works more efficiently, because each organization is doing what it does best.

As a consequence of this new focus, industries and organizations are undergoing fundamental shifts from large, organization-owned value chains to networks of specialized organizations, each focused on what it does best. This partnership helps them deliver greater value and increase overall financial performance. Internet applications allow organizations to interconnect with suppliers and partners and create an extended “virtual organization” that spans the globe.

In 2003, we wrote a book that describes the continuum for virtualizing business processes (The Case for Virtual Business Processes, Cisco Press, 2003). On the one extreme, a business automates nothing and out-tasks nothing. On the other extreme, the business chooses to outsource large parts of its value chain. This virtualization continuum makes clear that an organization can choose how much to outsource. We pointed out that the best place to be for most functions within the business is somewhere in the middle of the continuum. You do not want to put too much of your business in the hands of someone else; but you do not necessarily want to devote a large amount of your resources to performing functions that are not core competencies, either.

The key, of course, is to recognize the nature of core competencies. Anything that is fundamental to the creation of intellectual property in your business is a core competency. All other functions are peripheral and could conceivably be out-tasked.

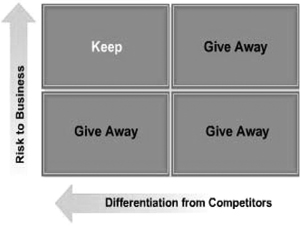

How can you identify your core competencies in practice? It turns out that you can apply two tests to a particular activity to determine whether it constitutes a core intellectual property for the business. The tests are to assess whether the activity constitutes a key differentiator from competitors, or if allowing another organization to perform the task would increase any risk factors of doing business to the firm.

The degree to which differentiation is a core competency is tied to the ease with which a competitor could reproduce it. If, for example, the difference between your product and that of your competitor is the color, that would be easily reproducible. The product would not be much different and would not be core to the business. Therefore, outsourcing color selection is a reasonable choice. If, on the other hand, the difference is profound, say a completely new function that the competitor cannot copy, it would be core and would represent a differentiator that you would not want to outsource. That is a segue to the second point.

Risk to the business would be increased if the color selection outsourcer happened to outsource to a third party whose quality controls were not of the highest standards. In such a case, the small differentiation of the product would be negated by the low quality. The risk to the business that the poor quality, such as uneven color tone, would significantly degrade sales is considerable.

Many activities, if outsourced, might constitute a risk to the business. At first blush, they might not be perceived as a source of differentiation, but they could still damage the business if done poorly. In the case of a service company that chooses to outsource its customer-facing service functions, this could be a high-risk decision.

To represent all this graphically, look at the table shown in Figure 2-8. The X-axis represents differentiation from competitors, with activities that directly contribute to the competitive advantage of your organization positioned on the left. The Y-axis represents risk to business, with activities that pose a high risk to your organization positioned higher up in the table.

Keep: You should perform activities in the upper-left quadrant within your organization. These are activities that both differentiate you from your competitors and have a high risk to your organization.

Give away: You should out-task or outsource activities in the other three quadrants of the table to qualified partners.

The next section looks at differentiation and risk to business in more detail.

By differentiating between activities that your organization should do itself and those that partners can do for you, your organization will be able to focus its resources on its core activities and leave less essential tasks to outside partners who specialize in those activities.

But how do you determine which activities to give to whom?

Look at the previous table in more detail. You should outsource some of the activities to partners and out-task others. What is the difference?

Outsourcing: The partner manages and oversees the entire process.

Out-tasking: Your organization defines and oversees the process, giving specific tasks to the partner to complete.

This section looks at the issue of which activities to outsource and out-task in more detail.

As you have already seen, you can evaluate any element of the value chain of an organization in terms of its differentiation from competitors and its risk to the business of the organization.

Differentiation from competitors: Your organization might outsource or out-task both core and context elements to partners. What you must decide is the degree of control over the process that your organization must maintain.

Our way (core): For processes that are a source of competitive differentiation, your organization must be an expert in that function and manage the process.

Your way (context): Your organization can delegate processes that are not a source of competitive differentiation to a partner who will manage the process.

Risk to business. Your organization might outsource or out-task both mission-critical and non-mission-critical elements to partners. Again, you must decide on the degree of control that your organization wants to maintain over the process.

Our standards (mission critical): Processes that are mission critical must adhere to the performance standards that you have developed.

Your standards (non-mission critical): Processes that are non-mission critical can use standards developed by a partner for whom this is a core competency.

So, as you can see, the context within which outsourcing and out-tasking are evaluated is the degree to which competitiveness is enabled. The dynamics within which this evaluation take place are differentiation and risk. In the next section, you will see how differentiation can be created in practice using IT.

This section looks at three case studies that involve companies attempting to achieve differentiation through the application of technology. After each case study is a worksheet where you should list the key differentiation that was achieved and note whether you think that this differentiation is reproducible by the competitors of the company. Also note whether you think that this differentiation would be a good candidate for outsourcing or out-tasking for the company in review.

Known for its innovative use of technology to streamline business operations and increase productivity, CEMEX turned an IT eye to its workforce. With a strategy of growth by acquisition, the company needed to unify newly acquired workers as well as employees across multiple countries. The solution: CEMEX Plaza, an employee portal that connects people to information and improves customer service and satisfaction.

Based in Monterrey, Mexico, CEMEX is the number-three cement company in the world and, since its acquisition of Southdown in 2001, the number-two cement maker in the U.S. Founded in 1906, the company today employs more than 25,500 employees and has customers across four continents.

Since mixing its first batch of cement in 1906, the company has followed a philosophy of continuous innovation. The stated mission of CEMEX is to serve the global building needs of customers and build value for stakeholders by becoming the most efficient and profitable cement company in the world. It has kept that promise by aggressively applying Internet-enabled solutions across the enterprise.

Using technology, CEMEX had become the most efficient cement producer in the world. But the company also wanted to ensure it was delivering the best customer service to strengthen its position as the preferred provider and partner in the construction industry. That meant it needed a way to link employees to knowledge management databases to raise the standard of customer satisfaction.

“We wanted to create a way for people from different countries and newly acquired companies to come closer together,” says Gilberto Garcia, IT planning leader for CEMEX. “Our chairman defines it as building ‘One CEMEX’ and sharing a ‘CEMEX Way’ of doing things.”

The vision was to establish a standard method to access contents, services, and applications needed to perform employee business functions. Critical success factors for the solution demanded that it be as follows:

Personalized

Secure

Valuable to the company, business processes, business units, and employees

Accessible from any computer with an Internet connection

Scalable and flexible to support CEMEX growth

Working with the Internet Business Solutions Group (IBSG) of Cisco Systems, CEMEX decided that it was time for a portal linking employees across the business. To build employee interest and help encourage cultural change, CEMEX held a contest to name the new portal. “We had a lot of participation, a lot of great ideas for naming the portal, but the best one was ‘CEMEX Plaza’,” says Garcia. “It was to connote a sense of a place where people come together to share information and news, conduct business, and debate important topics.”

As a component of managing culture change, CEMEX launched e-learning as one of the first applications on the portal. One of the first courses available at CEMEX Plaza was training on Internet capabilities. In addition to e-learning and access to company databases, other applications that have come online include a company-wide directory; E-Room, a tool for online collaboration; and E-Document for electronic document management.

From its beginning, CEMEX Plaza has grown from 1,500 to 160,000 visits per month. To date, the company estimates that it has saved U.S. $6.9 million in reduced costs and improved productivity on an investment of U.S. $3.6 million.

“CEMEX Plaza has become a very important tool because everything is there: company strategy, information about competitors, compensation information,” says Garcia. “It has become the most important channel of communication between employees and the company.”

As part of the portal strategy, CEMEX at first put global applications online. What the company realized is that there needed to be more local content to meet unique employee needs. “We came up with the concept of communities of practice, which allows for creation of customized content,” Garcia says. “Because it’s very expensive to create a community from scratch, we developed a toolkit that is very easy to use and not costly.”

Another “lesson learned” according to Garcia is to establish a governance model for portal content early in the process. “In the beginning, it was problematic,” he says. “Somebody needs to be empowered to make decisions about content and strategy. The community model is working well for us, with local people creating and managing local content. If I were to do this again, I would involve the business units and all geographies from the beginning. We designed the governance model when we were in the middle.”

Through all the expansion of capabilities, there has been no need to buy additional software. “Cisco defined a roadmap and IT foundation when we built the initial infrastructure, and at that time they recommended what we would need to evolve our e-enablement efforts,” Garcia recalls. “Because of the excellent work of this team, we have no problems with technology.”

CEMEX believes that the portal can keep delivering a return ratio of 100 percent of its investment each year, mostly in productivity improvements and cost avoidance. Always on the cutting edge, CEMEX plans to evolve CEMEX Plaza by adding new applications. “We are not satisfied with where we are,” Garcia observes. “We’re always looking for improvements. For the next phase, we’re looking to integrate more business intelligence capabilities into the portal.”

On the next page, list the CEMEX sources of differentiation and whether these could be outsourced or out-tasked.

___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ |

After tapping the expertise of the Cisco IBSG, delivery and transportation industry leader FedEx Corporation implemented Sales.fedex.com—a mission-critical, one-stop online source for sales tools and customer information that has spurred its sales force to generate an extraordinary 15 percent increase in sales productivity.

In 1971, current CEO Fred Smith founded what today is known as FedEx Corporation. Smith has capitalized on continuing technological innovation to build the enterprise into a worldwide behemoth with 240,000 employees and contractors with operations in 215 countries. Headquartered in Memphis, Tennessee, FedEx is a U.S. $25 billion family of businesses that offers a global network of transportation, information, and supply chain services. Those services are delivered through such well-known holdings as FedEx Express, FedEx Ground, FedEx Freight, FedEx Custom Critical, FedEx Trade Networks, FedEx Supply Chain Services and, most recently, FedEx Kinko’s.

Fred Smith has capitalized on continuing technological innovation to build the massive enterprise. The company was one of the first to harness the power of the Internet to provide fast, easy, and convenient service options for its customers.

FedEx made waves by launching a website in 1994 with a bold new package tracking application—one of the first true corporate web services. Over time, FedEx has continued to pioneer new technological territory, such as when it became the first transportation company with website features that allowed customers to generate their own unique bar-coded shipping labels and request couriers to pick up shipments. Today, Fedex.com hosts an average of eight million unique visitors per month and handles on average three million package tracking requests daily. More than 2.5 million customers connect with the company electronically every day, and electronic transactions account for almost two-thirds of the more than 5.4 million shipments FedEx delivers daily. Cutting-edge information technology is critical to the continuing success of the business—a fact supported by the contention of Smith that “information about the package is as important as the package itself.”

Chief Executive Magazine named Smith “CEO of the Year” for 2004, recognizing him for “building a $25 billion company that virtually invented an entire industry, transformed other sectors as diverse as manufacturing, retail, and transportation, and heightened expectations of globalization.”

The FedEx Services sales force comprises some 3200 U.S.-based professionals with approximately 30 percent engaged in telephone-based selling, 50 percent in the field, and about 20 percent in corporate sales. Like the rest of the company, the sales organization uses technology to deliver superior customer service. However, as a result of ongoing acquisitions and the consolidation of legacy IT systems, the FedEx sales tool—Sales Source—had become outmoded, unable to quickly and effectively supply the sales force with accurate, up-to-date product and pricing information.

Resources were scattered over several divisions and anytime-anywhere availability was lacking, recalls FedEx director of sales planning Denise Yunkun. “In the beginning we just kludged all the systems together,” she says. “When we took a step back and evaluated Sales Source, it became obvious that we needed to do something better in terms of giving our sales people performance and information tools as well as access to each other as a way to build best-practice momentum.”

“The vision for FedEx sales is optimum efficiency and effectiveness when it comes to interacting with customers,” adds senior vice president of FedEx Solutions, Tom Schmitt. “We needed to find ways to use technology that would point us toward the right conversation with the right customer in terms of value propositions—and then make it easy and effective to follow up with add-on products and value. We believed that technology could deliver the tools to do that.”

Beginning in 2002, a consultant from the Cisco IBSG met with FedEx sales and IT professionals. What began as a best-practice sharing session quickly evolved into a true collaboration effort aimed at transforming the FedEx Sales Source into a faster, more integrated, and productive sales resource.

Capitalizing on the consulting expertise of IBSG—and using the Cisco e-sales portal as a catalyst for new ideas—FedEx developed a new, online sales portal and toolkit called Sales.fedex.com. Matt Maddox, IBSG consultant, says the engagement with FedEx “evolved from simple best-practice sharing to true collaboration. Development teams from both sides met regularly, alternating between Memphis and San Jose, to share ideas and serve as unbiased sounding boards, with IBSG facilitating the relationship and managing the engagement. And the impact on Sales.fedex.com is clear. The functionality, as well as the look and feel, is so similar to e-sales that it looks like they were jointly developed.”

Sales.fedex.com also provides benefits to the company sales force by permitting constant contact from remote sales locations as well as accurate, real-time tracking of sales incentive compensation.

Sales.fedex.com is an integrated sales technology platform that creates a workflow around the sales function of FedEx, according to Sanjoy Haldar, manager of Sales Technology Strategy for FedEx Services. “Our sales professionals now can go to one place on the web and get all the tools and information they need to identify sales prospects, develop customized value propositions, enter calls, review shipping histories of particular accounts, plan follow-ups, and measure their own performance.”

Besides making it easier and more efficient for FedEx sales professionals to input relevant data and stay on top of customer information, Sales.fedex.com has helped to significantly increase productivity. “After about a year of utilizing the new Sales.fedex.com productivity tools, we had a 15 percent increase in time spent on actual selling,” Schmitt says.

Even though the company kept its sales force flat, that 15 percent improvement in customer facing time translates into 30 percent of the incremental revenue put in the plan for next year. This additional income will come from increased sales productivity.

In addition, the new online sales portal for FedEx includes tools that enable the company to identify the potential box and letter shipping needs of nearly every registered business in the United States. Based on that compilation, FedEx sales professionals have been able to target the highest potential customers and develop recommended call cycles to contact those businesses with value propositions built around their needs. The upshot is that the FedEx sales force is using its gain in sales time to contact more and more well-targeted, high-potential customers.

Given these kinds of productivity gains and increased customer contacts, Schmitt says FedEx is convinced it will realize its incremental revenue goal from sales force productivity improvements. “We’re confident we’ll get that because we believe our sales people are going to be significantly more efficient and effective with these tools.”

In addition to expanding Sales.fedex.com from its domestic U.S. operations to FedEx sites around the world, the company says its focus is on delivering even more sales information and performance management enhancements and on utilizing the online resource to improve customer relationship management.

“We’re integrating even more with our marketing divisions and want to pull more customer service information in,” Yunkun says. “We’ve provided faster, more integrated and effective access to tools from a sales perspective—pricing, territory management, compensation—and now we’ve got to bring other peripheral functions into the mix to give our sales professionals a better 360-degree view of the customer. And we intend to continue collaborating with Cisco. It’s like we’re sister companies—even though we’re in different industries, we share a common desire to do the right thing for our customers and our sales force.”

On the next page, list the sources of differentiation for FedEx and whether these could be outsourced or out-tasked.

___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ |

British Airways has made enormous strides since its privatization in 1987. Throughout the 1990s, it earned customer loyalty by focusing on industry-leading standards of service.

Recently, however, the air travel industry has experienced shocks on an unprecedented scale. At the end of 2001, British Airways needed to take a radical look at its operations to stay abreast of a fundamentally changed marketplace. The British Airways board of directors was very aware of the emergence of Internet technology and keen to get value from it for the entire business.

The British Airways Future Size and Shape program recognized the need for judicial investment to secure a real change in its business model. One of the ways in which British Airways realized that is through its eWorking program—simultaneously changing the culture to one of immediate self-service and delivering hard, tangible benefits to the company and its people.

The involvement of Cisco Systems helped accelerate achievement of those objectives.

British Airways (BA) launched an ambitious eWorking program that extends to every corner of its global organization. A total eWorking investment of U.S. $11.5 million allowed the company to save U.S. $110 million in less than four years.

The British Airways intranet has revolutionized the way the organization operates. eWorking includes intranet-based processes and tools that save both money and time in procurement, flight and cabin crew planning, and crew briefings, and provide global access to information at any time from anywhere. BA is now witnessing 4 million page views per month on its intranet site from BA people in the office, and 200,000 per month via the Internet from people at home or from crews down route. That figure is rising all the time.

Procurement Director, Silla Maizey, confirms that British Airways spends some U.S. $7 billion per year on goods and services ranging from aircraft purchases, through fueling and airport services, to office stationery and equipment. A large proportion of this expenditure is on things that the company can purchase more effectively via an eProcurement portal.

“For the company, the benefits are quite clear. For the individual, what is really good is that you can select from catalogues online. It is efficient; it is easy. In fact, you are in control of it all. From the company’s perspective, it is quite the opposite. It means we don’t have to manually intervene, so we introduce the fact that you do not have to have transactions costs, so compliance is higher,” Maizey explains.

The eRequisition system is part of strategic sourcing—which also includes eSourcing, eContracting, and eIntelligence. In addition to reducing prices, it enables continuous budget control and provides a highly effective platform for development of supplier relations. Silla Maizey says, “It’s a process from end-to-end. So that means that we identify the business need, we have a seven-step process that takes us right through sourcing goods, applying the right strategy to that sourcing, taking the RFIs, going through implementation, negotiation, and then managing and developing our suppliers.”

Introduced in March 2002, eRequisition was projected to save “tens of millions of dollars” a year within three years.

Crewlink Online is an intranet portal that gives flight and cabin crew access to a range of facilities including duty rostering and scheduling. Crewlink Online takes the complexity out of accessing relevant information, enabling people to take action themselves.

With regular flights to 219 destinations in 92 different countries, flight crew planning used to be highly complex, lacking the flexibility to enable flight crews to plan their duties to harmonize with their personal needs. Traditionally, flight crew planning involved sending out reams of paper-based information 6 weeks in advance to some 3500 flight crew members, who could then select which duties they wanted to be scheduled for.

eBidding brings together a huge volume of complex company and union rules and adds the concept of personal preferences or parameters.

Lloyd Cromwell Griffiths, director of flight operations, says, “Flight crew can put in a range of parameters and simply filter through the trips that match their requirements. Having given a pilot the lifestyle of his choice, we have a happy contented employee, which leads to two further benefits.

“The first is that we have the lowest sickness rate of any airline in the world. The second is that we are taking complexity out of the bidding process and speeding it up.”

Mike Street, director of customer service and operations, adds, “One of the key aspects of my job is motivation—motivation of 26,000 front-line staff but particularly 14,000 cabin crew. One of the key things that controls one’s life is knowing when you come to work, when you don’t come to work, and when you can have a day off for your friend’s wedding, or whatever you might want to do.

“If you feel you have some control over the way in which your work is arranged, then you are going to attend more frequently. You are not going to be likely to need to take an odd day off to attend a wedding, and you are going to want to do your work in a much better way. We have found that eBidding and ePreferential bidding have made a significant difference to the way in which work is allocated and to the general level of motivation and satisfaction of our crew.”

Ask Scheduling is another function accessed through the Crewlink Online portal or BA intranet, which seeks to answer crew rostering and scheduling questions online with little or no human intervention. It consists of a database containing frequently asked questions and answers, with the top 20 displayed on the first screen. Crew members can access the service at any time, from anywhere in the world, and search for answers to nearly all their questions.

Mike Street explains, “There are lots of questions that you would like to know about—the availability of leave, when you can have a day off—and we have a service within our eWorking processes, within our reporting center, called Ask Scheduling, and it’s just what it says. It is Ask Scheduling all the questions that you want to know.

“We used to do it largely face-to-face. Twenty-four hours a day there was somebody there that you could go and talk to. But you were reliant on that person’s interpretation of information. Today through the Ask Scheduling eWorking process, you get a consistent answer. “It gives information to the crew, information they vitally need. From the company’s perspective, it has cut down enormously on the administration costs. We now have a face-to-face facility open between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. instead of 24 hours a day, so you can see the cost reduction in that. We are getting great applause from the crew for providing this service, and the rate at which it is expanding is enormous.

British Airways, unlike many other major airlines, is owned entirely by private investors. Key statistics are as follows (preliminary results for financial year ending March 31, 2002):

265,000 private shareholders, including 49 percent of British Airways employees

Turnover U.S. $12,000 million (down 10.1 percent from previous year)

Operating profit negative U.S. $158 million (128.9 percent down from previous year)

Operating margin negative 1.3 percent (down 5.4 points from previous year)

More than 40 million passengers carried (down 14.8 percent from previous year)

755,000 tons of cargo carried (down 17.4 percent from previous year)

Overall load factor 64 percent (down 3.4 points from previous year)

360 aircraft and 57,227 employees (MPE—down by 2.8 percent from previous year) working in approximately 200 locations

In the fourth quarter, announced actions were having a significant effect on costs. Operating profit was positive (at around U.S. $50 million), cash burn was zero, and the airline had its largest year-end balance since privatization.

“It has been far more successful than I would ever have imagined, and in about three times the time that I was told that we would get to this level of interaction. So I’m very pleased with Ask Scheduling, and I know the crew are. They say so all the time. Already we are getting a thousand questions asked of it a week.”

eWorking is not only about providing access to information and the facilities to use it. It is also about ensuring that information reaches specific people with specific needs, such as flight crew who need detailed and effective preflight briefings.

Five years ago, it would have taken pilots at least 15 minutes to work through reams of paperwork to check weather reports along the route, calculate fuel loads, and much more. Today—through eBriefing—a pilot simply looks at a screen, taking 15 to 20 seconds to assimilate data that has been selected and sorted in advance.

Lloyd Cromwell Griffiths says, “The number-one requirement is that it is safe—that there is enough data in the briefing that it is safe for pilots to go flying. The second requirement is that it doesn’t take forever to give the briefing, and the third requirement is that the pilot is able to sift out from the briefing what is really relevant, really valid, needs to be read before they depart, and what actually can be read en route or is not so relevant to that particular trip, because we are buried by information coming in.

“By using crew briefing, we are able to highlight the areas that are relevant and demote down the page of the screen the areas that are not so relevant and so, for instance, a pilot operating a twin-engine airplane will have all the points relevant for his diversions.”

The major commercial benefits are that safety is improved by providing timely, accurate, and updated information, and the airline is always sure of flying the best route in the given circumstances.

British Airways now offers all staff remote access to its intranet over the Internet, externalizing some 90 percent of its intranet facilities and content to security-accredited members of staff, enabling them to use intranet facilities and functionality from their own homes or hotel rooms in far-flung places.

Although there is always an office-based alternative, more than 25,000 users each month are now accessing the intranet remotely. Intranet facilities are being extended to staff such as loaders, baggage handlers, and check-in staff. For example, 32 intranet access points have been installed at Heathrow, enabling front-line employees, who deal with British Airways customers on a daily basis, to access up-to-date information and consequently offer better service.

The combination of intranet facilities such as staff travel, online manuals, BA News interactive, People online, and online help desks is encouraging people to go to the web as their first port of call—and driving the desired culture change in British Airways.

British Airways has reduced its annual IT costs by 20 percent, but total technology investment has increased—running at U.S. $125 million for the current year. Total investment in eWorking currently stands at $11.5 million. Every project that British Airways undertakes must cover its costs within six months. Three years from now, British Airways will be saving U.S. $110 million every year from its eWorking program because of these investments.

Rod Eddington says, “eWorking is critical to British Airways. We employ nearly 50,000 people around the world, and we need to work together in a tightly integrated way, and eWorking allows us to do that.”

The speed and willingness with which the people of British Airways have adopted the web and eWorking shows that this was a revolution waiting to happen. The ultimate beneficiaries are the British Airways customers and shareholders but, along the way, the company is making the working lives of its people more fulfilling and more rewarding. As the British Airways eTransformation continues to accelerate, it is becoming an Internet role model for airlines throughout the world. British Airways has a reputation for innovation, and its use of the web will keep its competitors in trailing positions.

On this and the next page, identify the ways in which British Airways achieved differentiation through the use of IT. Is this differentiation sustainable? Does it constitute a core competency?

___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ |

This section reviewed several strategies for achieving success in the marketplace. These strategies included increasing productivity and decreasing costs. Cost reduction can involve the approaches of outsourcing and out-tasking, but care must be used in selecting activities to out–task, because they could be critical to core competencies.

One way to radically reduce cost is to apply the power of Internet-enabled IT to streamline core business processes by reducing overhead and increasing efficiency.

This section explores the three components that compose the business value of an organization:

Financial drivers

Business differentiators

Improvement disciplines

Why do shareholders invest in businesses?

The simple answer is to make money. However, this answer is not usually so simple, especially when the business in question is a start-up that has not had a chance to demonstrate revenue generation. In such a case, the question is more prospective and becomes this: can this business generate revenue sufficient to pay back my investment plus a profit? Or, in other words, is this investment risky?

It is the failure of business start-ups to understand this desire of investors to minimize risks and generate a profit that usually leads to problems. Businesses often view the acquisition of initial investment as some sort of lottery process that generates free money and no accountability. Reality is often a hard pill to swallow—especially when a start-up business owner discovers that the investors are impatient with the progress of the start-up and are willing to take control of the company to ensure its success. Many entrepreneurs have seen their companies taken away when revenues were not forthcoming quickly enough.

When business owners understand the ways in which investors assess risk, they are much better able to run their businesses in a way that is consistent with that assessment. This section will examine the business from the investor point of view. You will see that, fundamentally, this assessment rests on an estimation of company value.

This assessment begins with the business value framework.

You are probably familiar with the concept of business value because you likely use it when making your own purchases. When you go shopping for a car, for example, you are looking not only at the model of car and its features, but at the company behind it. Does the company have a good reputation? Does it have a focus on product quality, and does it have a reasonably solid financial base? Will it be around in a few years, when my car starts needing repairs? Car value, it turns out, is much bigger than just the car.

This is much like the process used to assess business value. Investors look at three dimensions: business differentiators, financial drivers, and improvement disciplines. Financial drivers are associated with growth, profit, and risk. Business differentiators are associated with innovation, quality, and productivity. Improvement disciplines are associated with prioritization, process, and people.

These three drivers, shown in Figure 2-9, can be thought of as forming a pyramid. Each needs to be satisfied, or the pyramid will fall. Each is critical to achieving a high value assessment.

Financial drivers are those attributes of a company that drive revenue in an efficient way. The two primary drivers impacting a value perception are growth and efficient productivity.

As you have seen, growth strategies are designed to maximize revenue. If a company employs strategies in such a way that revenue grows over time, the value perception of investors is increased. If a company fails to grow or grows less than the market in which it operates, the value perception of investors is decreased.

By the same token, productivity and efficiency are also important to investors. These attributes translate into cost control and are long-term indicators of the potential of the ability of the firm to grow in a sustainable manner. Investors are interested in whether costs increase in proportion to revenues or are increasing faster than revenues. Ideally, costs are decreasing in relation to revenues as a firm takes advantage of economies of scale.

As discussed, productivity and efficiency are important to value and value creating, and neither can be pursued in isolation. For example, online banking can reach a customer base in areas that might not have many bank branches. The acquisition of new customers at low incremental cost can lead to increased profits. Using the same example, online banking reduces the number of people needed to process transactions. This in turn reduces customer support or contact requirements, which increases efficiency, lowers cost, and grows profits. Figure 2-10 shows the flow of financial drivers to increase a firm’s profits.

For a publicly traded company, how is all of this reflected in its stock price? Stock prices reflect the investor estimates of growth, profit, and risk. As profit and revenue grow, so does the stock price. As the risk of the investment increases, the stock price declines. Of course, both of these dynamics happen at the same time, so stock price can be thought of as the capital market expectation of how profitable that organization will be in the coming years, adjusted for risk. This expectation of future profitability determines how much investors are willing to pay for a share of stock.

Revenue growth is assessed in terms of average annual sales over a period of years. In other words, one-time revenue growth is usually not sufficient to assess the revenue potential of a company. It is the sustainability of revenue production that eases the fear of risk for investors. The duration in years of sustained revenue growth is usually called the competitive advantage period (CAP).

Profit growth is driven by revenue growth coupled with cost controls. Cost controls seek to control both variable costs—those costs associated with production—and fixed costs—those costs associated with operations. In addition, cost control seeks to reduce the cost of assets and taxes. In practice, this means a focus on process management to ensure the most efficient production process possible within the constraints of good quality.

To the extent that investors see either poor revenue growth or poor cost containment, their perception of risk increases, and their perception of value decreases for the company.

Figure 2-11 shows the second driver for shareholder value as differentiation. Unless your business is completely unique to begin with, you are probably worrying about how you can make yourself appear different to your customers. Even commodity producers constantly look for ways to make their product more appealing to customers through more compelling packaging or other cosmetic differences.

Aside from purely cosmetic changes, though, how can your business achieve differentiation? It turns out that true business differentiation can be achieved through a business focus on innovation, quality, and productivity.

Innovation, of course, allows you to create completely new products that address customer needs in unique ways. This approach has been the preferred one for technology firms, especially those devoted to the information technology market. Innovation requires, though, that you free up the human and capital resources necessary to create it.

Quality is another way to achieve differentiation, especially in commodity markets. If your product is inherently better from a form, fit, and function perspective, it is probable that customers will prefer it to the product of your competitors, for whom the quality level is not as high.

Finally, productivity is an enabler of differentiation because, if you are able to produce a product more efficiently, all other things being equal, you should be able to free up resources that allow you to focus on improving quality and innovation.

These three pillars of differentiation allow a business to carve out unique pieces of a market. They are data points that serious investors research when deciding where to place their money. Venture capitalists, especially, tend to favor businesses that are highly differentiated.

The third leg that defines shareholder value is improvement disciplines, as shown in Figure 2-12. Improvement disciplines allow a business to devote resources to innovation, quality, and productivity. Since the era of the Japanese quality revolution, improvement disciplines have been at the forefront of business thinking.

Essentially, improvement involves a focus on three things: prioritization, process, and people. You learn how this works next.

Prioritization involves focusing your attention on what really matters. If everything is deemed high priority, nothing actually is, because you are constantly shifting from project to project, while nothing is actually accomplished. For a business to be successful, it must be able to decide what it will devote its resources to and, just as importantly, what it will not devote its resources to.

Deciding on what is important is the key to prioritization. Once again, priority, products, and projects are those that have the highest probability of contributing to the growth or differentiation of a firm. When in doubt, assign a higher priority to those that generate the greatest revenue.

Process improvement has been endlessly debated, and many structured approaches are available to address process management. Chief among them currently is Six Sigma, which attempts to evaluate processes in terms of defects per million attempts (DPMA). This approach is an outgrowth of Total Quality Management (TQM), which looks at processes statistically. Both process improvement methods are concerned with the idea of process control. If a process is in control, it is producing the highest quality possible for the least amount of overhead. If it is out of statistical control, the process can be improved to achieve a more efficient production dynamic.

Finally, people improvement focuses on the training of employees to adopt new skills that enable new business processes. Although many companies have chosen to achieve improving skill sets through attrition and replacement, over time, this approach becomes counterproductive as employees with critical knowledge of the company and its culture leave. A better approach, and more cost effective in the long run, is to hire good employees and then provide training to keep them current. Morale is improved this way, and the company does not hemorrhage talent over time.

The three drivers for shareholder value—financial drivers, business differentiators, and improvement disciplines—cannot be pursued independently. Each depends to some extent on the other two drivers, as shown in Figure 2-13. Improvement disciplines drive business differentiation. Business differentiation drives financial performance, as does improvement. However, without financial performance, neither differentiation nor improvement is possible.

Each of these drivers is important to prospective investors and shareholders. Each will be evaluated by the market and will, for publicly traded companies, determine the stock price. For private companies, these are still important, because they determine how willing private investors or venture capitalists will be to provide funding.

This section discussed the ways in which its constituents value a business. You have seen how financial drivers, business differentiation, and improvement disciplines work together to raise the value perception of investors who then express their value perception by the price they are willing to pay for stock. The next section examines how this works for virtual organizations: those businesses that are founded on information rather than fixed capital.

NVOs are a direct result of the revolution in computing technology that began in the late twentieth century and which reached critical mass with the dot-com bubble. As discussed earlier, this has led to a fundamental shift from fixed capital assets as a driver for business success to networked IT as the basis for success.

This section examines the NVO and its organization and then looks at some case studies that illustrate the power of the NVO approach in a business context.

In this section, you will learn about the following:

NVOs

The three key NVO strategies

NVO impacts on various industries and organizations

What is an NVO? It has many definitions. Cisco Systems, for example, defines an NVO in terms of its culture. John Chambers, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Cisco Systems, defines NVO as: “...a business model based on two basic assumptions: companies and government organizations will add value on a sustainable basis by focusing efforts on core capabilities. They will rely on systems and out-tasking partners for those responsibilities that others can do more effectively; at the heart of this model is increasing productivity using networking technology to appear as one virtual entity to their customers.”

The NVO concept first appeared in a book called The Virtual Corporation, by William Davidow and Michael Malone (1992). They wrote that the virtual corporation is a “corporate partnership model” that combines the strongest functions (core competences) of multiple companies:

Technology

Financial strength

Development capability

Branding

Their findings established that a single organization cannot manage all these competencies alone. Organizations need partners to succeed. Although Davidow and Malone conceived this idea before the explosion of the World Wide Web, organizations are now combining this idea of the “virtual corporation” with the Internet to run their organizations more efficiently.

We also wrote about such organizations when we published our book, The Case for Virtual Business Processes: Reduce Costs, Improve Efficiencies, and Focus on Your Core Business (Cisco Press, 2003). In that book, we took a somewhat different view of NVOs or, as we called them, virtual business processes. We defined a virtual business process as a process that leverages Internet-enabled IT to achieve significant increases in productivity and profitability.

The common thread within all these definitions is the idea that technology can allow a company to off-load the noncore functions to outsourcers so that investments can be made in those functions that are fundamental to the business: the core functions.

The network is the critical element that makes the NVO business strategy possible. The network links people, information, and processes to enable greater customer intimacy, innovation, value, and productivity. In essence, the organization that adopts an NVO business model has the capabilities to create and manage a networked virtual ecosystem (NVE) of companies. These companies work together for a specific purpose and for a specific period to deliver products or services.

NVO is, in essence, a new way of doing business. The NVO business model is based on three key strategies:

Customer centricity: An NVO responds rapidly to the needs of the customer. The customer needs come first, so an NVO puts them at the center of the organizational value chain, not at the end.

Core versus context: An NVO focuses on those elements of business functions where it adds the most value, has the greatest skills, or are its core competencies. It lets multiple partners perform noncore competency activities. Partners, however, must have the necessary skills to run these activities.

Continuous standardization: NVOs adopt standard business processes, standard sets of data, and standard IT systems throughout the organization to minimize costs associated with customization.

Groups of NVOs that partner to bring products and services to market operate in an NVE. When executed properly, an NVO business model increases productivity and reduces costs through the continuous improvement of core versus context evaluations of an organization. The most effective organizations follow all three strategies at the same time.

The next section looks at these strategies in a little more depth.