Constructive Politics: Essential to Leadership

Philippe Rosinski

Go into any organization and say the word politics, and you will see most people shake their heads disdainfully. It has a largely negative connotation, suggesting hidden agendas, manipulation, deceit, alienation, and jockeying for position. At worst, it is seen as destructive; at best, a necessary evil.

In my view, however, organizational politics does not have to be destructive. In fact, it is fundamental, essential to having impact as a leader. In order for it to be constructive, though, leaders must put aside their negative view, approach it systematically, and engage in it with a sense of purpose.

In my work coaching executives and senior management teams, I have found that it is helpful to think about constructive politics in terms of two dimensions: power and service.

In order for politics to be constructive, leaders need to put aside their negative view of it.

Power

I define politics as an activity that builds and maintains your power so that you can achieve your goals. Accordingly, power can be understood as the ability to achieve your meaningful, important goals. Politics is a process. Power is potential, and it comes from many sources.

External network. There is power from knowing and having access to key people in the environment outside the organization, people who are seen as being able to help the organization in some significant way—for instance, a potential large customer or an influential public figure. In addition, having a relationship with the knowledge people who are generating new ideas adds power.

Internal allies. Power also comes from developing a good relationship with key people inside the organization. One good way to do this is to contribute substantively to their work. Another good way to do this is to contribute in some way to their lives—for instance, providing a person with the opportunity to take part in a project that is especially important to him or her because it relates to a personal goal.

Having knowledge. It has long been said that “knowledge is power.” In today's organization, with the increasing focus on gaining competitive advantage through knowledge management, it is especially true. It is important, however, to distinguish knowledge from information. We are awash with information. What we need is synthesized, up-to-date information that is specifically related to pertinent organizational concerns—that is, knowledge.

When I work with executives, I seldom find that they have given any deliberate attention to the sources of power. so I typically brainstorm with them about what constitutes power; this helps them become aware of what they have overlooked and consider what actions they could take to gain influence.

One executive complained about the lack of resources allocated by top managers to his research and development division. He was cynical about their poor understanding of the strategic importance of R&D. At the same time, the president of the corporation was concerned that the division did not have real team spirit. He expected the division to articulate an overall vision of its contribution to the organization, not to mention a sound business plan.

In order to respond to these expectations, the R&D team had two retreats, over five days, to build trust and respect and then to design a strategic plan for itself. The plan started from a customer perspective and offered an integrated R&D approach that would serve customer needs better than any company in the market had ever done.

I described constructive politics to the team, which thereby became aware of external networking as a way to garner support from key customers so that it could then “sell” the plan inside the company. Before the retreat, these engineers had never thought of such political actions as a part of their jobs, but they realized they had to do this in order to gain the backing of top management. Their political actions, far from being destructive, brought win-win-win-win results: for the company as a whole, which improved its business; for the R&D division, which established a better relationship to the rest of the company; for customers, who got better service; and for team members, who made it possible for themselves to do more relevant and interesting engineering work.

Being credible. Credibility, too, brings power. If you are believable, seen as worthy of trust, and consistently demonstrate high performance, your ability to achieve goals is increased.

Generating choices. Providing yourself with alternatives in any situation can be a source of power. For instance, consider a situation in which a manager is negotiating with a computer vendor; if there is a range of models that meet the manager's quality requirements but the vendor has to meet sales targets, then the manager is in a position of relative power. It is best to avoid, consequently, becoming overdependent on a superior, subordinate, customer, or supplier.

It is important to distinguish knowledge from information. We are awash with information.

Formal authority. Having control of resources and decisions is the source of power that people are most familiar with. The growing appreciation of leadership without authority notwithstanding, formal authority remains politically important. Although authority alone is no guarantee that your goals will be accomplished, it does typically provide more resources and opportunities to put ideas into action. This can facilitate bigger success and increased visibility, which in turn can lead to further opportunities to achieve your important goals.

Interpersonal skills. Leadership study and training have often focused on interpersonal skills as a source of power. Persuasiveness, humor, assertiveness, respect for others, and the ability to embrace different perspectives are skills that increase your capacity to work effectively with others to foster support for and commitment to organizational goals (especially those aligned with your personal goals).

Intrapersonal skills. Power can also come from such abilities as individual creativity (the capacity to see problems from various perspectives and to frame issues in advantageous ways), physical fitness (energy and endurance), optimism, and mental skills (for instance, a good memory for facts).

Achieving important, meaningful goals is best accomplished when power is broad based. Therefore, you should consider consciously attempting to develop as many sources of it as possible. The next issue is how you should go about building and exercising that power—which brings us to service.

Service

Politics cannot be constructive if it is engaged in only for the benefit of the leader. It must work in the service of others: the stakeholders in the organization—superiors, subordinates, peers, customers, and shareholders—as well as society in general. You should attempt to understand the hopes, needs, and dreams of people and creatively seek common ground between their goals and yours. You want to be open to their wishes while staying true to yours, looking for synergies, for innovative win-win situations. It may also be that one of your goals is helping them achieve their goals.

Thus, as power gives impact and leverage, service guides your actions. Leaders vary in their relative orientation toward service, depending not only on the strength of their commitment to others and the number of others they are trying to help but also on their capacity to listen, empathize, trust, respect, share, and care.

Listen. The ability to hear people out, without assuming that you know what they are going to say or interrupting them to advance your own view, is crucial to constructive politics. It means accepting and honoring disagreement and having faith that you and the speaker will be able to work out a shared position at some point in the future.

The ability to hear people out is crucial to constructive politics.

Empathize. In addition to listening to another person's position and understanding it intellectually, empathizing means that you are able to imagine yourself completely in the person's situation and understand his or her feelings and what causes them. Sometimes feelings, and not just ideas, must be addressed.

Trust. Trust is also crucial to constructive politics, but what is called for is not blind acceptance. Rather, you need to develop the ability to tell when people are being authentic and therefore likely to be consistent in their actions, and factor this into your plan for how to achieve your goals.

Respect. Respecting people and the work they do is key to service. This can be difficult in organizations that particularly value certain kinds of work, such as financial analysis or strategizing, and downplay others, such as support functions.

Share. Although you cannot make the mistake of trying to convince everyone to take your view of a situation, you also cannot neglect to let them know what your position is. This makes it possible for other people to understand and evaluate your words and actions.

Care. Probably the most important capacity that you can bring to service is the choice to care. Without it, the other capacities cited here are in danger of being merely instrumental. I'm talking about, in the words of the psychologist Alfred Adler, “a deep feeling of identification, sympathy, and affection in spite of occasional anger, impatience, or disgust . . . about genuine desire to help the human race.” As inappropriate as it may sound in the corporate world, I believe that service is fundamentally about love.

The most important capacity that you can bring to service is the choice to care.

Taken together, these abilities, with their underlying service orientation, can give direction to the building and use of power.

Politics in Practice

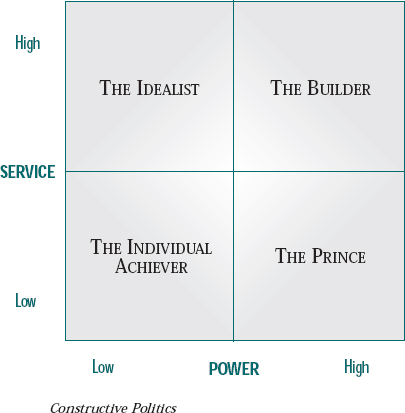

I have found that a good way to understand the interaction of the two dimensions of constructive politics, power and service, is to think of four basic political types (which can be arranged in a two-by-two matrix). These types can then be used to help you understand both your short-term and long-term needs with respect to developing constructive politics.

The Individual Achiever

With a low service orientation and not much power, the individual achiever is seen as self-centered. This type can have a high technical competence and be very successful at some activities—think of a lone rock climber who can negotiate a long vertical ascent. If the conditions are right—with a protective boss or in a situation with few interdependencies—the individual achiever will likely not feel powerless or feel the need to engage in politics. In an interdependent situation, however, he or she may be very frustrated by the inability to focus on and productively engage in the technical work.

If the conditions are right, the individual achiever will not feel the need to engage in politics.

The Idealist

The idealist has a genuine desire to serve others but is low on power. often seen as a crusader, this type may succeed through perseverance but is often frustrated by bureaucratic obstacles. The tendency of the idealist is to resent politics; often this is because he or she is avoiding conflict. The idealist may also, because of the focus on others, devalue self-affirming activities that relate to personal goals. In some cases, this results in blaming others for failure and unconsciously playing the victim.

The Prince

The prince, as described in the classic work by Machiavelli, has a lot of power but is largely committed to, or is understood as being largely committed to, self-advancement. Although often seen negatively, this type can make things happen and achieve objectives. However, the prince runs a high risk of alienating people, which in the long run can erode power.

The Builder

With a desire to serve others and well-developed power, the builder is the type that is most likely to be described as “a leader.” This type can use politics to help people identify and respond to the challenges necessary to achieving the organization's mission. The builder has personal goals, and accepts that other people do too, but he or she uses the energy that comes from these in the service of people in general.

The builder has personal goals and accepts that other people do too.

Developing Constructive Politics

There are both short- and long-term aspects to developing constructive politics. For the long term, it is important to understand that there is value in each of these types. Each can do good work and learn. Therefore, one long-term aim might be to go eventually through all the types. (The path you take in accomplishing that is likely to be far from a straight line.) Ultimately, it is crucial to recognize that gaining power in order to serve people with impact is a legitimate development aim.

For the short term, you should keep in mind that the types are dynamic and yours will vary, particularly with respect to the sources of power, as situations change. Thus, it will be helpful for you to consider the following questions:

Gaining power in order to serve people with impact is a legitimate development aim.

Question 1: Where am I now in the two-by-two matrix? In order to answer this, first consider the sources of power: How many do you draw from and how strongly? Then evaluate yourself with respect to the service-related capacities: How many of them are you accomplished in? Think of how your current situation relates to your type.

Question 2: Given my current situation, where would I like to be now? In order to answer this, think of someone you admire who is effective in the current situation and consider where he or she fits in the types.

Question 3: What do I need to do to get where I want to be? For instance, it is not uncommon for a leader to be an idealist but to be dissatisfied with what he or she can accomplish. Such a person may decide to work at having more power, increasing the range of sources he or she draws power from, thus becoming a builder.

The ideas in this paper are evolving and have come from four sources: the business, sociological, and psychological literature; contact with managers and executives in CCL programs; ongoing action research, which includes my interviewing people in senior leadership positions about their experiences with organizational politics, particularly with respect to power and service; and of course, my own experiences in organizations, including six years as a software engineer and project manager in Silicon Valley and in Europe.

I have attempted to present these ideas in a suggestive rather than exhaustive way, while keeping them true to the sources. For instance, politics is often defined primarily with respect to power—consider, for example, Philip Sadler: “The process of achieving, maintaining, and exercising power is called politics” (“The Politics of the Corporate Jungle,” Director, 45[10], 1992); Jeffrey Pfeffer: “Politics and influence are the processes, actions, and behaviors through which . . . potential power is utilized and realized” (“Understanding Power in Organizations,” California Management Review, 34[2], 1992, an article excerpted from Managing with Power); and Ronald Clement: “Politics is power in action; it involves acquiring, developing, and using power to achieve one's objectives” (“Culture, Leadership, and Power: The Keys to Organizational Change,” Business Horizons, 37[1], 1994). For the purposes of my action research, I have synthesized these views into the following definition: politics can be understood as an activity (or process) intended (1) to build and maintain power and (2) to exercise power to achieve goals.

If you are interested in participating in action research on constructive politics, please contact me by e-mail at [email protected], by fax at 32-2/346-41-37, or by telephone at 32-2/340-02-10.

Another common situation is that a leader who is a prince is concerned about a legacy, how he or she will be remembered. Such a person may decide to concentrate on using power to serve others, thus becoming a builder. This requires developing the abilities necessary to serve others.

Whatever the desired change, in order to use politics constructively, I have found that executives need to assess and then address power and service in a systematic way.

Conclusion

Seeking power in order to engage in constructive politics is a legitimate and necessary leadership activity. There is much talk today about the need to change leadership so that it can help us build meaning and community, bring more human resources to bear upon the challenges of complexity, and come to decisions that work for us all. Instead of tearing organizations apart, politics, if it balances power and service, can play an important role in the evolution of such leadership.

Politics, if it balances power and service, can play an important role in the evolution of leadership.

SUGGESTED READING

Block, P. Stewardship: Choosing Service over Self-Interest. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1993.

Crozier, M. Le phénomène bureaucratique. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1962. (Available in an English translation by the author as The Bureaucratic Phenomenon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.)

Greenleaf, R. K., Frick, D., and Spears, L. On Becoming a Servant-Leader. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996.

Pfeffer, J. Managing with Power: Politics and Influence in Organizations. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996.

Philippe Rosinski is program director for CCL in Brussels, Belgium. He has an electrical and mechanical engineering degree from the École Polytechnique in Brussels, a master's degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University, and a Cepac postgraduate business degree from the Solvay Business School in Brussels.

For those who would like to know more about the people, programs, activities, and events at the Center for Creative Leadership, CCL publishes a quarterly newsletter, On Center. Contact CCL Client Services for information about how to obtain it: 336/545-2810 (telephone) or 336/282-3284 (fax).