The Renault-Nissan Alliance Negotiations

When news broke in 1998 about the alliance talks between Renault and Nissan, auto company executives called it “the most improbable marriage in the world” (Thornton et al., 1999). Even the wedding arrangements involved major challenges. The companies’ negotiators faced contrasting national cultures, very different languages, and a complicated agenda. Opposition to the relationship came from various corners: Nissan’s chairman, Japanese government officials, Renault’s unions, and stock analysts protective of Renault’s cash (Edmondson et al., 1999). In early March 1999, Renault CEO Louis Schweitzer bleakly assessed the odds of actually having a “wedding” at only 50/50 (Lauer, 1999a).

Yet the talks attracted public and industry attention, for they presaged “the next big deal” after the mega-merger of Daimler-Benz and Chrysler in mid-1998. An agreement between Renault and Nissan would create the world’s fourth-largest automaker. For some observers, this marriage would also signal the opening of continental Europe’s auto industry to foreign—specifically, Japanese—competition. In Japan, media reports evoked the possibility of the first turnover of management control of a major Japanese industrial company to a foreign enterprise since 1945.1

For negotiation enthusiasts and scholars, the Renault-Nissan talks represent an interesting case study. Why did Schweitzer choose Nissan as a partner? How can we effectively understand his negotiations with Nissan president Yoshikazu Hanawa? What lessons can international negotiators learn from this experience, which produced a highly beneficial agreement? This case investigates these questions with an approach known as negotiation analysis and shows how Schweitzer and his team could have used it prior to their negotiations. We provide an account of the actual talks and conclude with a discussion of pros and cons of negotiation analysis.

Elements of Negotiation Analysis

“Advice should promote an understanding of problems.”2

Negotiation analysis was originally developed to provide negotiators with advice (Raiffa, 1982). It was “analysis for negotiation, not of negotiation” (Raiffa, 2002, pp. xi, 11). But even advising a negotiator involves “understanding the behavior of real people in real negotiations” and viewing counterparts in descriptive terms. Moreover, the use and forms of negotiation analysis have evolved over the past 20 years (see, e.g., Sebenius, 2002).

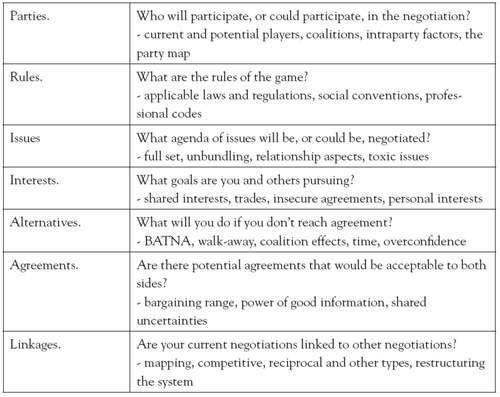

Watkins has developed a framework for nonspecialists that may be used to identify and assess the “essential features of [any] negotiation’s context and structure.” Such “diagnosis,” as he labels it, focuses on seven elements of negotiation (see Figure F.1). The next section fleshes out each element for the Renault-Nissan negotiation.

Figure F.1. Diagnosing the negotiation situation (Watkins).

Diagnosis of the Negotiation Situation

“[Renault] saw an opportunity that comes up once every 50 years.”3

Consider Schweitzer’s position in mid-1998 as he looked at the possibility of negotiations with Nissan.

At age 56, he had been CEO for 6 years. He began working at Renault in 1986 as the CFO, after a career in the French ministries of finance and industry. Renault was then trying to emerge from a deep financial crisis. It was dramatically transformed by 1992 when Schweitzer took over. Four years later, however, Renault lost $1 billion. In a controversial move, Schweitzer called for more cost reductions. He managed to turn the company around and by 1998, was credited with restoring its reputation.

Established 100 years ago, Renault S. A. was France’s 2nd (the world’s 10th) largest automaker and 44.2% government-owned. The company produced a full range of cars, commercial vehicles and parts, and employed over 138,000 people. It operated in over 100 countries, although 84% of sales originated in Europe. Total consolidated revenue for 1997 was EUR31.7 billion, and in mid-1998, the market value of Renault shares had reached EUR12.7 billion ($14.5 billion).

Renault was at a critical juncture. The world auto market in 1998 was in its worst slump in 20 years, Japanese competitors continued to beat Renault on cost, and the industry was consolidating rapidly. Industry analysts were pointing out likely acquisition targets. Some analysts considered Renault “distressed or inefficient”; others unequivocally labeled it “ripe for takeover” (Vlasic, 1998). Renault management itself was shocked into questioning the company’s future when Daimler and Chrysler merged in May 1998 (Ghosn & Riès, 2003. p. 173). When the executive committee began looking into possible marriages with other automakers (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, p. 174), American and European companies were quickly set aside. Renault approached Nissan, and Nissan responded (Lauer, 1999b).

Schweitzer and his team started preparations for negotiations with Nissan with the idea of a limited collaboration (e.g., a manufacturing tie-up in Mexico). Soon, however, they contemplated a much broader interfirm relationship. What follows is the authors’ projection—not an actual account—of how they could have applied Watkins’s 7-point analysis prior to the first formal intercompany meeting in July 1998.

Parties

Given the significance of the project, Schweitzer would meet with his counterpart at Nissan, President Yoshikawa Hanawa. A small group of executives and advisors on each side would participate initially in the talks. Later, more players would become involved. Identifying these parties was the first step in the analysis for Schweitzer’s team.

Current Players (Direct Participants)

Schweitzer’s inner circle for the tightly guarded “Pacific Project” included Executive Vice-Presidents George Douin and Carlos Ghosn. Douin, who oversaw product and strategic planning and international operations, had conducted the early studies of potential Asian partners and would spearhead advance work for the CEOs’ talks. Ghosn was a cost-cutting expert who masterminded Renault’s post-1996 restructuring.

Other key parties on Schweitzer’s side of the negotiations are shown in Figure F.2. They included Renault’s board of directors, French ministries, and agencies such the Treasury Department and the Work Council at Renault. For full-fledged negotiations, Schweitzer would have to add investment bankers, legal counsel, and other specialists.

The Nissan side would be led by president and CEO Hanawa. He had been in the job for only 2 years, but at Nissan for 40 years. His experience spanned positions in planning and in overseas operations, including a stint as chairman of Nissan’s manufacturing arm in the United States. Nissan Motor, Japan’s second-largest automaker, had a proud, 90-year history. The company dominated Japanese car manufacturing until the 1960s and earned a reputation for excellence in engineering. With a strong international orientation, including production sites in 22 countries and sales in more than 180, it spearheaded the Nissan Group, which comprised 1,300 subsidiaries (Douin, 2002, p. 4). The Group employed 130,000 people and generated about $58 billion in consolidated revenue. Nonetheless, by 1998, Nissan Motor (hereafter, Nissan) had been in financial trouble for more than a decade.4

Figure F.2. Parties to the upcoming negotiations (Schweitzer’s view).

This was Schweitzer’s first contact with Nissan, so he and his team would be hard-pressed to foresee all whom Hanawa would include on his advance and negotiating teams. Some research would reveal a few likely participants (e.g., Yutaka Suzuki, General Manager of Corporate Planning). Nissan’s board of directors, like those of many Japanese corporations, was not likely to hold back or counter a strong chief executive like Hanawa. Other parties could be added to the “party map” (Figure F.2) as they came onto the scene.

Potential Players

In addition to these central characters, other players could affect the Renault-Nissan talks or their outcome. On the Renault side, potential players included unions (e.g., Confédération Générale du Travail), nationalistic politicians, French government officials outside the Treasury and Ministry of Industry, and agencies of the European Union, such as the EU Competition Bureau. Investors besides the government, given its golden share (veto power), were probably not a significant constituency.

The Renault team knew far less about Japan. They might well wonder about the role of Nissan’s industrial group, the Fuyo keiretsu. It contained Nissan’s largest shareholders and creditors (Fuji Bank, Industrial Bank of Japan, Dai-Ichi Mutual Insurance). Nissan’s history was laden with labor strife; its unions (e.g., Nissan Roren) were cause for concern. Japanese government agencies, such as the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and Ministry of Finance, were known worldwide for their strong influence on Japanese business.

The most noteworthy of all potential players were perhaps other automakers—those willing to make a play for Nissan or even for Renault. Daimler-Benz already had talks under way with Nissan Diesel (a truck and bus manufacturer 39.8% owned by Nissan Motor) about a tie-up in commercial vehicles. The new DaimlerChrysler co-CEO Jurgen Schrempp might expand their scope (see “Linkages”).

Coalitions

Schweitzer’s team could scan for coalitions likely to support or block a Renault-Nissan relationship (Figure F.2). The unions, fearing job losses, might mount opposition with support from key government officials. They did just that through a “Euro-strike” in 1997 when Renault announced the closing of its Belgian plant. On the other hand, a proalliance coalition might be built across the two companies with various players and probusiness officials.

Rules of the Game

The Schweitzer-Hanawa and other intercompany talks would be governed, explicitly and tacitly, by “rules of the game.” Watkins (2002, p. 12) describes them as laws, social conventions, and professional codes of conduct (see Figure F.1). Some apply to all business transactions; others are specific to the transaction type.

In broad terms, the convention for large-scale negotiations between multinational firms was to begin with a high-level invitation and reply, move into closely guarded, exploratory discussions and, if they were promising, continue into negotiation of a memorandum of understanding or letter of intent. Then formal negotiations, for which executives typically brought in a cast of other professionals, would aim to produce a detailed agreement or contract.

Other practices and expectations would stem from the particular type of relationship that Schweitzer sought with Nissan. A “merger game” would be driven by concerns about control, share prices, and competitive offers from other suitors; talks would be secret and expedient. Acquisition-like negotiations could entail a whole range of subgames and tactics. With an alliance, the parties would concentrate on their relationship and qualities as prospective partners (Dussauge & Garrette, 1999, p. 5).5

The Schweitzer team would have to identify French and Japanese policies and laws in areas such as foreign investment and joint ventures, labor regulations, trade regulations, foreign exchange, intellectual property, technology protection, taxation, and antitrust and competition. In France, antitrust matters were handled by the Ministry of Economy and by EU bodies. Workers’ rights were protected by both French and EU agencies. France’s Labor Code required management to inform the company’s work council of “any changes in the economic organization of the company” (Sarrailhe, 1994, p. 122). In Japan, regulations applicable to Renault’s initiative were set forth in the Commercial Code (administered by the Ministry of Justice), in Foreign Exchange Law, in Foreign Trade Control Law, in Anti-Monopoly Law (the Fair Trade Commission), and in Securities and Exchange Law (the Ministry of Finance) (Cooke, 1988, p. 303). An investor with more than 33.3% equity in a company had the right to veto board decisions (Lauer, 1999b).

These are only a few examples of rules. Schweitzer and his team also needed to learn much about Hanawa’s and Nissan’s customs, for the team had little experience with Japanese culture and business practices.6 One such practice was the limited use of outside counsel, which coincided with general practice in France (Sarrailhe, 1994, p. 128).

Issues

Schweitzer’s initial letter to Hanawa in June 1998 simply proposed that they explore ways to enhance their companies’ competitiveness. In the third step of negotiation analysis, Schweitzer’s team would develop an agenda of issues to be negotiated. This meant pinpointing substantive business topics, relationship aspects, and any “toxic” issues.

Business Matters

In addition to the central issue of the basic type of relationship or venture, there were numerous topics for discussion. Major business issues for a joint venture included venture scope and strategic plan, contributions of the parties and their valuation, and management control.7 The legal form of the venture would have to be discussed. Formation of an equity joint venture required articles of incorporation and bylaws. Legal issues arising from policies described under “Rules” would come into play as would questions about transfers of technology and proprietary property, the right to compete, dispute resolution, governing law, and duration and termination of the agreement (Klotz, 2000, pp. 257–258).

Relationship Aspects

The purpose of considering relationship factors in negotiation analysis is to spot preexisting negatives and points of conflict. In this case, the slate was clean. None of the information available to the authors revealed a prior relationship between Schweitzer and Hanawa. But there were impediments. The French and Japanese had limited experience with each other, and negative impressions persisted. In Japan, according to Renault Executive Vice President Douin (2002, p. 3), the French had a “poor image…[as] not an industrial [power]…arrogant, not very serious, and volatile.” The Renault team would have to prove themselves.8

Toxic Issues

Among the issues that might be “exceedingly difficult to agree on” (Watkins, 2002, p. 17), the most sensitive were likely to be management control and price. For Hanawa and his team, the future of Nissan Motor and its management had to be highly charged issues. Schweitzer realized that the Japanese public also would be concerned about a takeover, especially a foreign takeover (Douin, 2002, p. 3). The price of equity in Nissan, too, was likely to be strongly contested, for notwithstanding its financial status at the time (see “Interests”), it was a proud company. Renault had more than $2 billion in cash, but its own financial history and government supervision required Schweitzer to be very careful with it.

Interests

Schweitzer’s letter to Hanawa had been motivated partly by the DaimlerChrysler announcement. It had reemphasized a basic, underlying concern—what negotiation analysts call an “interest”: surviving industry consolidation. Yet Schweitzer and Hanawa had several interests—corporate as well as personal—to try to satisfy through negotiation.9

Renault’s interests included the following:

• Heightening its ability to compete (quality, cost, and delivery time)

• Accelerating the internationalization of the company

• Continuing its momentum as a revived enterprise

• Achieving sufficient scale (critical mass) in the auto industry

• Developing a worldwide reputation for product innovation

• Protecting its home market share

Schweitzer wanted Renault to be “the most competitive” in its markets (Renault, S. A., n.d.). He was intrigued with Japanese production techniques and sought ways to shrink Renault’s 36-month R&D cycle to as low as the 24 months found in Japan. His predecessor had shifted Renault’s focus from volume to profit; Schweitzer wanted to move it to quality.

Internationalization would ease Renault’s heavy dependence on the mature West European market. In the large, competitive U.S. market (23% of the world total), Renault had no presence. In Asia and other non-European markets, Renault had no reputation or a poor one. Schweitzer wanted to change that by capitalizing on the company’s innovativeness in product design. Attaining critical mass (taille critique) made sense both defensively, to fend off possible bids, and offensively, to compete effectively. Last, Toyota—a fierce competitor—was scheduled to start production in France.

Nissan’s evident and conceivable interests included the following:

• Providing debt relief

• Preventing a hostile takeover/protecting the Nissan identity and brand

• Reestablishing a strong position in the critical U.S. market

• Returning the company to profitability

• Improving its competitiveness in Asia and Europe

• Proposing an effective solution for bleeding Nissan Diesel

• Ensuring the long-term health of Nissan Motor

• Preserving jobs

Nissan had to cover about ¥4,600 billion ($33 billion) in current liabilities by March 1999. The company had not declared a profit in 5 of the last 6 years, and its debt-equity ratio was over 5 to 1. Nissan was vulnerable competitively and financially and given current merger and acquisition trends, had to be worried about moves by competitors and investors at large. In the U.S. market, where Nissan had dominated Toyota and Honda until the mid-1980s, Nissan had fallen to third place with a 5% share. Its cars were viewed as dull and expensive. In Europe, Nissan had led Asian automakers in the market for 20 years, but lost the position in 1998. Nissan Diesel had been an albatross since the mid-1990s and, in 1998, reportedly had “huge” debt. Last, in a national business environment in stagnation but renown for lifetime employment, Nissan management would probably still be concerned about employees’ livelihoods.

Shared Interests

The two companies clearly had common and complementary interests. One common interest was long-term health. Nissan was the more financially strapped of the two, but analysts still considered Renault “in play.” Both companies were living among giants in the industry. The two CEOs had each decided to focus on improving competitiveness (cost cutting), strengthening their presence in the United States, and polishing their corporate images.

Complementary interests included product lines and market presence. Renault’s emphasis on product innovation fit Nissan’s need to depart from dull, undistinguished cars. Nissan wanted to recoup its position in Europe, a market that Renault knew well. Conversely, Renault had little experience in Nissan’s home territory. In Executive Vice President Douin’s (2002, p. 3) words, the two companies had an “almost miraculous complementary relationship.”

Priorities and Trades

Schweitzer and his team could identify priorities and locate potential trade-offs (Watkins, 2002, p. 22ff). If they offered Hanawa enough cash, he would probably relinquish some management control. Schweitzer might obtain production technology and know-how by granting access to product design. Improving competitiveness versus protecting jobs was just one more of several possible trade-offs.

Personal Interests

Schweitzer had noteworthy interests of his own. He presided over the unconsummated—some say failed—merger negotiations with Volvo in 1989–1993 and knew the Renault-Nissan would attract extraordinary media attention, so he had no desire for a recurrence of that kind (Lauer, 1999a).

It was a safe bet that Hanawa felt even more strongly that his personal reputation and face were at stake. He did not want to be responsible for exacerbating Nissan’s condition or for that matter, not rescuing the company as a variety of stakeholders counted on him.

Alternatives

How could Schweitzer advance these various interests if he did not reach an agreement with Hanawa? What was his best alternative to an agreement (BATNA)? What was Hanawa’s?

Renault’s Alternatives

Renault had two general options: “go it alone” or join another major automaker. Some observers felt that, with its cash, Renault should fund its own entry into the United States. The company could increase its competitiveness by hiring experts, licensing Japanese technology, or entering limited scope agreements with small automakers (which was already under way). But these measures would not accelerate internationalization of the company nor quickly move Renault to critical scale.

With respect to alternative partnerships, Renault did not have much to offer any of the world’s top five (GM, Ford, Toyota, VW, DaimlerChrysler). In Europe, Fiat and PSA had little to offer Renault. Schweitzer and his team had narrowed the list of candidates to a few Korean and Japanese automakers. The Koreans had too many problems to be a real option (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, pp. 174–175). Among the Japanese, only Nissan responded (Lauer, 1999b). Schweitzer’s BATNA, or best alternative to a negotiated agreement, was to go it alone—not a very attractive alternative.

Nissan’s Alternatives

Hanawa also had limited alternatives in June 1998, as Schweitzer’s team, via negotiation analysis, could well have surmised. Borrowing from commercial banks would be costly for Nissan, given its credit rating. Its main banks in the keiretsu had themselves fallen on hard times. Selling shares or issuing new equity would be ill timed since Nissan shares carried only 50% of their value a year ago. Spinning off Nissan Diesel and other subsidiaries, while possible, would not raise sufficient cash. Moreover, each option addressed only a single interest: satisfying creditors.

To meet its full set of interests, Nissan was more likely to try to partner with another automaker. Schweitzer and his team had to ponder whom else Hanawa would contact. Among the U.S. firms, GM was already allied with Toyota, and Ford was managing Mazda. Ford, however, had previously collaborated with Nissan on a minivan project. Among Japanese automakers, the large companies—archrival Toyota and Honda—probably saw Nissan as undesirable, and small companies saw it as too big to digest.

Thus, Nissan’s BATNA appeared to be an internally led restructuring based on its 1998 Global Business Reform Plan and short-term assistance from fellow keiretsu members. Given the scale and scope of Nissan’s needs, this was a rather weak BATNA that favored Renault. (When negotiations got under way, though, Nissan’s BATNA would improve considerably.)10

Agreements

For the sixth of the seven steps in the negotiation analysis, Schweitzer and his team would try to define the bargaining range, or “zone of possible agreement” (Raiffa, 1982), between Renault and Nissan and draft potential agreements. The latter would prime the team to push the negotiations in particular directions and to respond to Nissan’s proposals.

Consider, for instance, the matter of an equity investment by Renault. In addition to the $2 billion available in cash, say Schweitzer were willing to raise half again as much in funds for a total of $3 billion. Using a total market value for Nissan shares of ¥1,230 billion, he might seek 34.5% of Nissan’s equity (at ¥142/$1). For $3 billion, however, Hanawa might offer only 25% if he valued the company at ¥1,700 billion.11 If these were Nissan’s maximum and Renault’s minimum share figures, there would be no zone of possible agreement.

For the talks to progress, Schweitzer and his team would have to create a zone by adopting other valuation criteria, inducing a recalculation by Nissan, or altering their own bottom line. The team’s latitude might be constrained by the 33.4% threshold for an investor to gain veto power in Japan and the 40% level at which French accounting standards required an investor to assume the target’s debt (Lauer, 1999b). Alternatively, Schweitzer’s team might bundle equity share with other issues (see steps 3 and 4) in packages of offers.

Part of this effort would entail identifying the uncertainties shared by the companies. Consumer demand in key markets, stock market trends, and rulings of regulatory bodies in Japan, France, and the European Union were just a few of the open questions. To cope with them, the team could create multiple scenarios (Watkins, 2002, p. 38).

Linkages

Finally, the negotiation analysis would turn to negotiations that could influence the Schweitzer-Hanawa talks. Such negotiations might precede or follow the talks (in either case, a “sequential” linkage) or take place concurrently. Other possibilities included “competitive” linkages, when a party negotiates with two separate counterparts but can only agree with one, and “reciprocal” linkages, where agreement is conditional on reaching other agreements (Watkins, 2002, p. 41).

Figure A.2 could serve as a template for connecting parties and deciphering linkages. In June 1998, Schweitzer must have been especially concerned about the potential effects of Renault’s relationship with the French government and about negotiations that Hanawa might undertake. Quickly, let us look just at these examples.

Renault-French Government Linkages

The French administration, in roles ranging from shareholder to regulator, could impose various constraints and demands on Renault. The Socialist government would be preoccupied with jobs and public reaction. This multifaceted relationship could entangle Renault in antecedent, concurrent, and reciprocal negotiations. To make these possibilities concrete, Schweitzer and his team had only to recall the Renault-Volvo breakup, which many observers blamed on the French government’s role.

Competitive Linkages

Here the main question was whether Hanawa would play Renault against its competitors. Schweitzer had to consider actions behind the scenes as well as out in the open. In July, the very month Schweitzer planned to meet Hanawa, DaimlerChrysler announced an agreement to coproduce light trucks with Nissan Diesel and an intention to buy Nissan Motor’s stake in Diesel. That would keep Diesel off the table in Renault-Nissan talks. No other Nissan-DaimlerChrysler discussions, if any were in fact occurring, were made public during the summer, but Schweitzer had to wonder. (Within 4 months, he would have to contend with a competitive, concurrent negotiation involving these companies.)

The Actual Negotiations

“It’s a question of seducing rather than imposing.”12

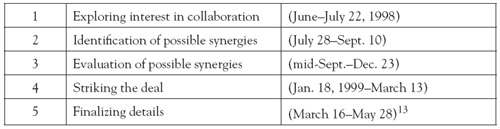

Hanawa’s reply to Schweitzer’s letter set in motion a series of communications and negotiations that stretched from July 1998 to March 1999, when the two CEOs signed a contractual agreement. This 9-month period may be divided into 5 phases:

Using public sources, the following section describes these negotiations.

During Phase 1, a small, select number of Renault and Nissan representatives secretly explored their respective interests in strategic collaboration. Schweitzer envisioned an alliance—a “subtle balance”—between the two (Douin, 2002); he had categorically rejected the idea of an acquisition or merger (Korine et al., 2002, p. 22). On July 22, in Tokyo, the two CEOs met for the first time. They quickly established rapport (Korine et al., 2002, pp. 42–43).

Over the next 7 weeks (Phase 2), working groups undertook a series of preliminary studies on each company, on topics ranging from purchasing to distribution, to identify benefits of an alliance. The results were promising. Moreover, Nissan’s capabilities in large cars, research and advanced technology, factory productivity, and quality control complemented Renault’s in medium-sized cars, cost management, and global strategy for purchasing and product innovation (Douin, 2002, p. 3; Renault, S. A., n.d.). On September 10, Schweitzer and Hanawa signed a memorandum of understanding committing the companies to more extensive studies and to an exclusive arrangement until December 23.

During Phase 3 (September to December 1998), 21 intercompany teams assembled from 100 specialists on each side examined Renault’s and Nissan’s respective operations. The teams visited plants, held meetings at nearly every one of the companies’ sites worldwide, and exchanged proprietary information, such as costs and profit margins. Most information was readily transferred. As one reporter (Lauer, 1999a) observed, this was remarkable in an industry where companies jealously guard their manufacturing secrets. Top management intervened in the study teams’ efforts when necessary to facilitate collaboration (Lauer, 1999a), and progress was reviewed every month by a coordinating committee. (The study teams were prohibited from communicating with each other and reported directly to the two chief negotiators.14) At the top level, the main concern during this period was development of a business strategy; financial issues were left for the final rounds. Schweitzer and Hanawa continued their series of meetings, as did their negotiation teams, with venues ranging from their home cities to Thailand, Singapore, and Mexico.

Within Renault, Schweitzer and his negotiating team concentrated on refining their concept of an alliance. They drew on their experience with Volvo (Korine et al., 2002, p. 46). They scrutinized the Ford-Mazda tie-up as a model, paying particular attention to financial and cultural dimensions (Barre, 1999a; Lauer, 1999a). Ghosn and 50 Renault researchers began taking daily Japanese classes (Diem, 1999). Schweitzer has said the team was guided by the French maxim, “To build a good relationship, you do things together and look in the same direction together” (St. Edmunds & Eisenstein, 1999).

By October, the negotiations focused on a Renault investment in Nissan.15 It was probably about this time, if not before, that Schweitzer sounded out key French government officials about the alliance. He obtained a free hand, with support from as high as Prime Minister Jospin (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, pp. 182–183). Meanwhile, Hanawa set 4 preconditions for a deal: retaining the Nissan name, protecting jobs, supporting organizational restructuring already in progress at Nissan with Nissan leading the effort, and selecting a CEO from Nissan’s ranks.

In mid-November, Nissan’s board of directors took the extraordinary step of inviting Schweitzer, Douin, and Ghosn to Tokyo to present their vision of the alliance. The presentation went well; the Renault team sensed it was a turning point (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, p. 178.) But Hanawa was still actively seeking alternative partners. He approached Ford CEO Jacques Nasser (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, p. 176), for example. Nasser declined.

Sometime in November, Hanawa called on the new DaimlerChrysler co-CEO, Jurgen Schrempp, in Stuttgart. Schrempp boldly proposed an investment in Nissan Motor.16 Hanawa informed Schweitzer that he intended to follow up on Schrempp’s offer, yet he continued negotiations with Schweitzer.

During the next month, Renault and Nissan’s negotiating teams hit an impasse over the legal form of the relationship. Renault had suggested a subsidiary or joint venture. Nissan found neither acceptable.17 Renault EVP Ghosn stepped in and successfully proposed an informal alternative (see the final agreement).

Later in December, as they neared the expiration of the September memorandum, Schweitzer and Hanawa negotiated over, among other things, a freeze clause. Hanawa was not willing to lock in just yet. On the 23rd, the two CEOs signed a letter of intent, minus a freeze clause, for Renault to make an offer on Nissan Motor by March 31, 1999. Hanawa asked Schweitzer to include Nissan Diesel in the offer.

Phase 4 of the negotiations (January to mid-March) began with Renault’s first public, albeit guarded, acknowledgment of its talks with Nissan, but the period was punctuated by the competing Nissan-DaimlerChrysler negotiations (Lauer, 1999a). DaimlerChrysler not only provided Hanawa with a BATNA for the Renault negotiations, it had its own pull. Nissan management admired Daimler (Mercedes). They saw Renault as “no better off than Nissan in terms of future viability and survival,” whereas DaimlerChrysler had deep pockets (“Gallic Charm,” 1999; “Shuttle Diplomacy,” 1999).

On the Renault-Nissan agenda, Renault’s cash contribution was a tough issue. Nissan sought $6 billion. Renault had initially expressed interest in a 20% stake, and if Nissan were valued between $8.7 billion (market value) and $12 billion (comparable companies), a straight 20% stake would yield no more than $2.4 billion.18 Very quickly, Renault moved toward 35% (Lauer, 1999a) but not intended to reach 40%, where they would have to consolidate Nissan’s debt. With DaimlerChrysler in the wings, fluctuating share prices and exchange rates, and breathing space Nissan got from a long-term, ¥85 billion loan from the state-owned Japan Development Bank, it is no wonder that financial issues were contentious.

The negotiating teams continued their discussions through the winter. Nonetheless, on February 25, a Nissan spokesman denied that a Renault deal was imminent and asserted that talks with DaimlerChrysler were under way. In a way, this may have confirmed Schweitzer’s fears that DaimlerChrysler was the favorite (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, p. 176).

In mid-March, the circumstances for Renault improved dramatically when Schrempp formally withdrew his bid for Nissan Motor. DaimlerChrysler’s board of directors, leery of Nissan’s financial condition and understated debt at Nissan Diesel, had not given him the go-ahead (Barre, 1999b). Hanawa probed Ford’s CEO again about a linkage but without success. Schweitzer realized Hanawa’s choice was now “Renault or nothing” (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, p. 179).

According to two sources (Ghosn & Riès, 2003, pp. 179–180; Korine et al., 2002, p. 45), Schweitzer’s team restated the terms of their standing offer. The rationale for not reducing it, with DaimlerChrysler gone, was consistency. Schweitzer was trying to develop a particular type of relationship, and he did not want Hanawa to feel Renault would exploit Nissan.

A differing account of the March 10–16 period reports that Schweitzer sent the following confidential message to Hanawa, “There is hope that Renault will be able to make a larger investment than we proposed earlier” (“Shuttle Diplomacy,” 1999). Schweitzer did not specify the amount and instead asked Hanawa to trust him, but he also insisted on a freeze agreement by March 13. He needed it to go to his board. Hanawa finally acceded, flew to Paris on the deadline, and signed the document during a short layover.

On March 16, the beginning of Phase 5 of the negotiations, Schweitzer obtained internal approvals he needed from the Renault board of directors and Work Council (Renault Communication, 1999). These decisions centered on a 35% stake for $4.3 billion (Lauer, 1999a; cf. Korine et al., 2002). Negotiations with Nissan intensified, and in the final agreement reached 11 days later, the investment was up 20% to $5.4 billion for 36.8% of Nissan Motor and stakes in other Nissan entities. Public accounts do not make clear whether previous offers already included “other entities” and, if so, why Renault increased its offer.

The “global partnership agreement” signed by Schweitzer and Hanawa on March 27, 1999, outlined an alliance in which Renault and Nissan would cooperate to achieve certain synergies while maintaining their respective brand identities. The strategic direction of the partnership would be set by a Global Alliance Committee cochaired by the Renault chairman/CEO and the Nissan president/CEO and filled out with 5 additional members from each company. Financial terms included a Renault investment of ¥643 billion ($5.4 billion) in Nissan. For ¥605 billion of the total, Renault received 36.8% of the equity in Nissan Motor and half of Nissan Motor’s share in Nissan Diesel. With the remaining ¥38 billion, Renault acquired Nissan’s financial subsidiaries in Europe. The agreement included options for Renault to raise its Nissan Motor stake and for Nissan to purchase equity in Renault. With respect to personnel, Renault became responsible for 3 positions at Nissan (COO, Vice-President of Product Planning, and the Deputy CFO). A seat on Renault’s board of directors was designated for Hanawa. At the alliance level, 11 cross-company teams were set up to pursue key areas of synergy (e.g., purchasing, product planning) and to coordinate marketing and sales efforts in major geographical markets.19

Pros and Cons of a Negotiation Analytic Perspective

“Understanding: the power to make experience intelligible.”20

This article began with two questions about the Renault-Nissan talks. First, why did Schweitzer choose Nissan? Second, how can we effectively understand his negotiations with Hanawa? Now we can consider how well negotiation analysis answers these questions.

Schweitzer’s Choice

Regarding why Schweitzer initiated talks with Nissan in June 1998, Watkins’s (2002) framework provides a rationale. It can be seen in Schweitzer’s interests and alternatives: sharpened competitiveness, faster internationalization, and long-term survival. Meeting these interests through a partner seemed more expedient than going solo. Nissan had interests strikingly similar and complementary to Renault’s and was in critical shape financially. Schweitzer’s alternatives were bleak. So it made sense for him to contact Hanawa for talks.

This explanation assumes rational pursuit of self-interest and rests on retrospective, deductive logic, but it also has at least preliminary descriptive validity. It stands up to Douin (2002) and Ghosn’s (Ghosn & Riès, 2003) firsthand accounts of deliberations at Renault. In a press conference, Schweitzer himself cited two factors: the tough Asian market and the health of Nissan compared with Mitsubishi’s (Lauer, 1999b).

Schweitzer’s team had additional choices to make throughout the negotiations (see Ikle, 1976, pp. 59–75). One was the final choice of entering into a contractual agreement with Nissan.21 For these decisions as well, negotiation analysis offers credible explanations.

Understanding the Negotiations

The second question concerns the Renault-Nissan negotiations as a whole and asks what picture—or how much of the picture—negotiation analysis develops. The “Diagnosis of the Negotiation Situation” illustrates use of Watkins’s (2002) framework in the prenegotiation period. If this were an observer’s only perspective, how effective or useful would it be?22

Given limited space, let us look at three pros and three cons. The cons are disregard for the negotiation process, parochialism, and implementation issues. The pros, with which we will start, are essential features, an outcome orientation, and evaluation criteria.

Essential Features

Watkins’s framework covered basics—the whos, whats, and whys—of the Renault-Nissan negotiations. It allowed us to understand why Schweitzer contacted Hanawa and why they engaged in protracted negotiations. Moreover, this perspective highlighted Hanawa’s motivations for entertaining DaimlerChrysler and Ford as white knights and prompted questions such as why Schweitzer apparently increased his offer price after DaimlerChrysler withdrew. The set of key concepts in negotiation analysis thus brings out some essential features of a negotiation picture, facilitates insights, and promotes understanding.

Outcome Orientation

The second major contribution of Watkins’s perspective is a sense of purpose and direction. Negotiating is usually not an end in itself. Three elements of the framework—interests, alternatives, and agreements—turn attention to the destination, or outcome, of a negotiation.

In the Renault-Nissan analysis, we saw the importance of an alliance agreement that would slash Nissan’s debt and raise both companies’ competitiveness. We looked at a bargaining range for the equity issue and saw how much Schweitzer might have to spend for certain levels of equity, which, in turn, enabled us to evaluate proposals and track substantive progress in “The Actual Negotiations.” In view of the fit between the companies’ interests and weakness of their BATNAs, negotiation analysis anticipated an agreement (versus nonagreement) between the companies.

Evaluation Criteria

Third and finally, Watkins’s diagnostic framework provides sound criteria for evaluating a party’s results or gains from the final outcome of negotiation.23 A good result should at least satisfy a party’s interests and match its BATNA.

We can thus examine the final agreement in the Renault-Nissan case and compare its terms to Renault’s interests. The alliance structure ties the two companies together so closely that they may be seen as a single competitor, one with the critical mass Schweitzer considered vital. The commitments to find synergies and to coordinate marketing correspond directly to his interests in heightened competitiveness and internationalization. On the other hand, the price Renault agreed to pay for Nissan equity assumes a value of Nissan close to that based on the comparable companies calculation earlier in this article; it clearly favored Nissan.24

Such evaluation rounds out the picture of a negotiation, particularly if it is extended to all parties’ results. (Strictly speaking, negotiation analysis is an asymmetric, or one-sided, perspective.) Although the full value or impact of a deal of this kind can really be appreciated only later, interests and alternatives are still applicable criteria at those future points.25

Disregard for the Process of Negotiation

The most obvious and important drawback to this perspective is its distance from the negotiation process: the dynamic, ongoing interaction of the parties—the series of actions and reactions that precedes and produces a final outcome. Negotiation analysts deliberately omit the process (Raiffa, 2002, p. 11; cf. Watkins, 2002, pp. 72–101), whereas other negotiation scholars (e.g., Greenhalgh, 2001; Sawyer & Guetzkow, 1965) treat it as the very center of the picture—a moving picture—of a negotiation. Our narrative of the Renault-Nissan talks illustrated aspects of process and supplied pieces missing from the negotiation analytic picture.26

Parochialism

Watkins (2002, p. 8, 43) views his diagnostic framework primarily as a means of identifying barriers to agreement. That wholly negative orientation is unnecessary. Moreover, several elements of the framework are narrowly or incompletely conceptualized.

Parties, which are defined as “those who will participate” (Watkins, 2002, p. 8), are largely treated as sets of interests. The framework ignores other attributes, such as parties’ resources and capabilities, and assumes rational pursuit of interests, all of which limit an observer’s ability to probe interests, appreciate them in context, and explain or understand a party’s negotiation behavior on grounds other than preference maximization.27 Our profiles, which cited Renault’s $2 billion cash hoard and dazzling product designers, and Nissan’s renowned manufacturing techniques and U.S. market know-how, lie outside the framework proper. Yet resources are the means of satisfying interests and a source of bargaining power distinct from a strong BATNA.28 Further, the parties in the case differed in type, from individuals to entire organizations. It was the narrative, not the framework, that described actions and activities such as the Renault team’s preparations, Ghosn’s presentation to Nissan directors, and Hanawa’s last-minute flight to Paris.

Another parochial conceptualization in Watkins’s framework is parties’ relationships. They are regarded as problems—potential impediments to an agreement (Watkins, 2002, p. 15)—and as a minor, not main, consideration. But there was much more to the Renault-Nissan and CEOs’ relationships. Schweitzer himself considered the relationship dimension of the talks “indispensable” (Korine et al., 2002, p. 45). In general, relationships, whatever their form or nature, can be construed as the connectedness and connections—the interdependence and interactions—between parties. So relationships represent a context for parties’ actions and corresponding influence, a target for new efforts, and a perspective by which to make sense of their thoughts and actions (Weiss, 1993).

The last conceptualization of note here is rules, which Watkins presents as the sole, readily apparent context for a negotiation. In the Renault-Nissan case, other aspects of context included market conditions, fluctuating share prices and foreign exchange rates, and challenging circumstances for negotiators’ meetings. (Recall the variety of forums, scale of the undertaking, and impositions on headquarters separated by 9700 km.) These various conditions deserve consideration before and during negotiation, whether they are internal or external to a party and specific to one party or jointly applicable (Weiss, 1993). Moreover, conditions may facilitate action, not just constrain it. Watkins’s framework also presumes that parties will play the same game, whereas our case involved multiple legal systems and jurisdictions, and different political and economic systems. Some conditions conflict and require resolution. In sum, an exclusively negotiation analytic perspective may distort the picture of the playing field. Corresponding explanations for parties’ interests, actions, and accomplishments may only touch the surface or at worst, misdirect attention.

Implementation Issues

Several elements of Watkins’s (2002) framework are not defined in detail or described with explicit guidelines or subelements (recall Figure A.1) for fleshing them out. With parties, for instance, it is not clear how to represent an organization or whether to include agents as well as principals. This lack of specificity may allow for application to a variety of negotiations, but it leaves much to figure out for a particular case. Further, each element in the diagnostic framework is presented statically, without regard for how it might vary, shift, or evolve. In contrast, our narrative of the Renault-Nissan talks showed that is often just what happens. In the same vein, Watkins (2002) has not shown how to make connections between elements of his framework. How, for instance, do issues relate to interests, rules to alternatives, and rules to possible agreements (not to mention process to outcome)? In Reynolds’s (1971, p. 7) words, a sense of understanding depends on “fully describing links between concepts.”

Conclusion

This case study sought to further understanding of the Renault-Nissan negotiations and to explore the usefulness of negotiation analysis in that role. The foregoing discussion applied and assessed that perspective. It also hinted at general lessons from Schweitzer’s experience.

With respect to the Renault-Nissan negotiations, this case study identified the parties involved, their likely motivations, issues, and other influencing conditions. It also described parties’ actions and events during the 9-month period. We learned a great deal about the negotiation structure, content, and process.

The negotiation analytic perspective, as represented by Watkins’s (2002) 7-point framework, contributed significantly to that understanding. Focusing on Schweitzer’s interests and alternatives clarified his motivations and provided a logic for his choices. With its focus on essential features, an outcome orientation, and evaluation criteria, this perspective informed and complemented the account of the actual talks. At the same time, negotiation analysis by itself did not complete the picture of the Renault-Nissan negotiations. We learned where this perspective is inadequate by juxtaposing the diagnosis and the narrative. Findings from other Renault-Nissan studies reinforced this view.

Finally, this study suggests important lessons for negotiators. One is the huge impact of no-deal alternatives, particularly when they are made real. Hanawa put considerable effort into improving his alternatives while negotiating with Schweitzer, whose alternatives happened to be weak. It is important to identify, to evaluate, and to track a counterpart’s alternatives and to try to improve one’s own. Perhaps the most valuable lesson from Schweitzer’s experience is the power in the combination of exhaustive work on core substantive matters and careful development of a mutually satisfactory relationship. In a sense, Schweitzer and his team’s approach to these negotiations paralleled the main components of this case study: negotiation analysis and negotiation process. The Renault-Nissan negotiations were far from the quick, superficial courtship—the “shotgun marriage”—that some commentators (Woodruff, 1999) labeled them. Schweitzer and his team prepared for and conducted negotiations in ways that laid a strong foundation for Renault and Nissan’s successes in the postnegotiation period.

*This case was prepared by professor Stephen Weiss at York University, Toronto, Canada. It is printed here with his permission.