4

Lies About Managing the Learning Function

Edward A. Trolley

Sixteen years ago, David van Adelsberg and I wrote Running Training Like a Business because we were hearing the same concerns about training from senior executives with whom we spoke, and we were seeing the same structural and financial challenges with training at companies with which we interacted (van Adelsberg and Trolley 1999).

At that time, many training organizations had large staffs and large fixed costs. Training groups were pervasive across the organizations, and they were doing their own thing. So consistency was lacking, quality uneven, and spending underleveraged. Training professionals were domain oriented, not business oriented; they were focused on building their own programs, not on finding the best possible solution. Success was measured by volume—classes, courses, and training days—rather than by value. Vendors were accessing organizations anywhere they could get in and through as many people as they could find. Some training programs were delivering questionable value and focused on activity instead of application. Organizations took no real stewardship over training, relegating it to a “backroom” activity—a significant, but difficult to quantify, cost. They did not view training as strategically linked to business.

As a result, executives did not know how much they were spending on training, nor could they articulate the business value they were getting from their training investments. And they often thought training organizations were out of the loop, operating separately from the business. These executives saw a widening gap between the skills their businesses required and the skills the workforce actually showed. They saw training as part of the employee contract and a good thing to do for employees, but believed the investment–value equation was broken.

Today’s Reality

Fast forward to 2015. Is the training industry really all that different than it was 16 years ago? Certainly. We’ve had to figure out how to design and to deliver training differently. We’ve also had to figure out how to use technology differently. We’ve had to figure out how to use blended learning, mobile technology, simulations, gamification, social platforms, performance support systems, and talent management systems. More learning is being done informally than formally. Industry professionals are using new buzzwords. Learners have changed, technology has changed, tools have changed, the business and competitive environment have changed, and budgets have changed. The list goes on.

But what hasn’t changed? How we manage training. When it comes to managing training, the more things change, the more they stay the same. In fact, the list of what hasn’t changed when it comes to managing the learning function is pretty long.

In 2011, NIIT, a leading supplier of training services, commissioned Corporate University Exchange (CorpU) to conduct research to see how companies were performing against the key tenants of Running Training Like a Business. NIIT wanted to find out if the concepts were still valid, given that the book was written more than a decade previously. Studying more than 150 companies, CorpU found that only 18 were high-performers in running training like a business, measured primarily by whether they delivered quantifiable value to the business (CorpU 2011). That is not much different from the situation in 1999, and this is why I contend that the more things change, the more they stay the same. From this research, CorpU put forth five must-dos for effective training organizations:

![]() run at the speed of business

run at the speed of business

![]() be lean and agile

be lean and agile

![]() ensure a laser-focus on business (to drive business value)

ensure a laser-focus on business (to drive business value)

![]() provide data-driven analytics (to prove business value)

provide data-driven analytics (to prove business value)

![]() drive innovation.

drive innovation.

To what degree are you doing these five things? How are you making them happen? This is not rocket science. Successful business must take these actions each and every day.

In 1999, we said that the beginning of the beginning, the first critical step, is getting connected to the business—what we called business linkage. We meant that training had to become laser-focused on what’s important to the business and provide learning solutions that advanced the business’s goals and objectives. If not done correctly, nothing else would really matter. The training on which companies spend so much money would be irrelevant. Businesspeople would look at training as a cost, not an investment. Training professionals would forever be on the outside looking in on business discussions. And of course if times got tough, training would be at the top of the list for cutting costs.

Sixteen years ago, we offered guidance on how to strengthen business linkages, but it remains a significant issue for too many training organizations. Business leaders continue to question the value they receive from their very large investments in training. At a recent conference I attended, a panel of CLOs scoffed at the idea that they needed a seat at the business table, suggesting that way of thinking has passed. But those days are not over. It is even more critical today that training becomes intimate with business and delivers the value that warrants an invitation to conversations among business executives.

If we are going to build the business linkages we need to be successful, we must:

![]() Create roles in our training organizations that interact continually and consistently with business executives.

Create roles in our training organizations that interact continually and consistently with business executives.

![]() Train the people in these roles to engage in meaningful business conversations with their customers, using questions that elicit actionable information.

Train the people in these roles to engage in meaningful business conversations with their customers, using questions that elicit actionable information.

![]() Know the expectations of business executives and whether we are meeting them.

Know the expectations of business executives and whether we are meeting them.

![]() Assess and document the capabilities required to meet business objectives, quantify the gaps in capabilities, and design strategies that can close the gaps.

Assess and document the capabilities required to meet business objectives, quantify the gaps in capabilities, and design strategies that can close the gaps.

Let’s not offer 1,000 e-learning courses that no one uses, ask businesspeople what training they need (when they should be looking to us to help them figure it out), or assume that training is the only solution. In other words, let’s be businesspeople in training, not training people in business.

Managing (Formal) Learning

Everyone is talking about 70-20-10 these days. Agree or disagree with the ratio, what is hard to disagree with is that a lot of learning happens informally. But companies still spend more than $200 billion on formal learning each year. The questions, then, are: How well are we managing formal learning? Do we really know how much we are spending, what we are spending it on, what we are getting for it, or if it is aligned to the business? Do executives understand the business value they are getting? All indications suggest that we don’t have good answers to these questions.

Every day we see companies trying to get a better handle on how much they are spending and the value they are getting in return. But at the same time, we see companies with highly decentralized models, where training happens everywhere, that say they don’t really care if the same vendor is being used for the same programs in different parts of the organization, or if the company is being charged different fees for the same content. We also see different vendors offering the same types of programs, but with inconsistent content, uneven quality, and, of course, wildly different pricing.

And then there is training administration. Large companies have full-time teams devoted to providing training administration, as well as numerous part-time training administrators across the organization. In many cases, higher-paid learning professionals spend some 30–50 percent of their time performing administrative tasks. Training administration is a critically important, but low-value-added, activity. It consumes human and financial resources. We need to figure out how to do this largely transactional work differently to reduce costs, free up key resources, and improve overall quality and control.

Delivering or facilitating training is also undermanaged. Many employees do this as a small part of their jobs. They may be technical experts and top performers, but that does not necessarily make them good teachers. Facilitation is a professional craft. Why trust it to people who are not experts? It is not unusual for learning leaders to say that they use full-time trainers less than 50 percent of the time. (I recently talked with a learning leader who said she uses full-time trainers less than 20 percent of the time.) So, once again, are you managing learning as effectively as you could?

And, finally, how are you managing custom content development? Do you have a staff of instructional designers and content developers? Are they professionally trained, or did you find them from somewhere else in the organization because they were available? Are you holding yourself to the same standard that business leaders would hold the chief information officer for having staff with deep, relevant technical expertise? These are the questions you should be asking as you evaluate how you are managing the learning function.

As a training leader, if you are not looking for ways to continually improve effectiveness and efficiency, and you are not open to new and different ways to increase value, reduce cost, move fixed costs to variable costs, and gain access to better capability, you are not serving your company to the best of your ability. I encourage you to step back, take a hard look at what you are doing and how you are doing it, identify options for you to improve, evaluate those options, build business cases, and then make decisions that benefit your company.

At a learning conference I recently attended, one speaker said that the work we are doing in learning is serving a noble cause. And I agree. But unless we are helping our company be more competitive and productive, grow at a rate that business executives expect, give employees the skills they need to be more effective, or reduce costs and provide unmistakable value to customers, our work may also be irrelevant. The days of training being a good thing to do are no longer enough for business executives. When they see large sums of money invested in training, but are unsure of the value they are receiving in return, they are sometimes left no choice but to move investments elsewhere.

Measuring Value and Impact

How do you respond when someone asks you about measuring the value of training? It’s too hard. It can’t be done. There are too many factors. We can’t quantify the value. It costs too much. We can use other indicators instead of hard business measures. These are simply not acceptable answers. Let’s look at what business executives say. A 2009 ROI Institute study found that:

![]() 96 percent of executives want to see the business impact of learning, yet only 8 percent receive it now.

96 percent of executives want to see the business impact of learning, yet only 8 percent receive it now.

![]() 74 percent of executives want to see ROI data, but only 4 percent have it now.

74 percent of executives want to see ROI data, but only 4 percent have it now.

Do we really think our responses are acceptable? Our business executives certainly don’t. If we continue to ignore or sidestep this measurement question, we are destined to be the first to go when times get tough.

Let’s end this debate and start doing the heavy lifting to define the quantifiable business value we deliver from our work. Let’s understand what our customers need. Let’s ensure that we understand how they will measure success (the measurements they think are important) before we begin to do the work. Let’s define the factors that could impact the results. And then let’s help our customers measure the value against the measures they defined at the beginning.

The ROI Institute study said that business executives want hard evidence. So let’s give it to them, because without it, we give them no choice but to conclude that there is no evidence.

A Different Perspective

Over the years I have written about, talked about, and debated what I believe are the essential leadership actions we must take to dramatically move the needle on how we manage training and how we drive transformation. While it is hard work, and it might require that you think differently about things, I believe that we must transform (Table 4-1).

Table 4-1. Change in Perspective for Learning Leaders

| From | To |

| Training department | Training enterprise |

| Cost of training | Investment in learning |

| Attendees or participants | Customers |

| Measuring activity | Measuring results |

| What training you need | What business problem you are trying to solve |

| Training as the end result | Business outcomes as the end result |

| Mastering content | Improving performance |

| Allocation of expense | Pay for use |

| Activity | Application |

| Smile sheets | Customer success |

While one could argue that Table 4-1 oversimplifies things and suggests that the columns are “either/or” instead of “and,” the point is that we must start to think differently about the work we do.

Most importantly, while we all agree that developing employees continues to be both critically important and the right thing to do, the context has to be about delivering real business value. Training’s feel good charter is out of date (and has been for a while), and business executives expect more.

Why now? As someone once said: “It’s the economy, stupid!” And that was before the recent economic downturn. Never before have the pressures been so intense. Every day, we see increased pressure on:

![]() CEOs, executives, and business leaders to deliver more revenue, higher earnings, and greater shareholder value

CEOs, executives, and business leaders to deliver more revenue, higher earnings, and greater shareholder value

![]() functional (nonrevenue producing) organizations, including HR, to demonstrate impact and value

functional (nonrevenue producing) organizations, including HR, to demonstrate impact and value

![]() learning and development to demonstrate their relevance almost daily, reduce costs, and dramatically improve measurable impact.

learning and development to demonstrate their relevance almost daily, reduce costs, and dramatically improve measurable impact.

And never before has the business case been stronger and the mandate clearer, as indicated by the 15th Annual PwC Global CEO Survey, which stated:

More CEOs are changing talent management strategies than, for example, adjusting approaches to risk: 23 percent expect “major change” to the way they manage their talent. And skills shortages are seen as top threat to business expansion…. One in four CEOs said they were unable to pursue a market opportunity or have had to cancel or delay a strategic initiative because of talent. One in three is concerned that skills shortages impacted their company’s ability to innovate effectively. (PwC 2012, 20)

Actions We Should Take

It’s easy to talk about all the problems and challenges and to ask: “What should we do?” Here are some transformational steps that learning leaders should seriously consider.

Conduct a business assessment of training. This means far more than confirming the professional competency of the training staff, measuring activity levels, or even documenting that skills are being applied on the job. It means assessing the strategic and financial return earned on the training investment. It means looking at everything—people, products, processes, technology, and customer satisfaction and value being delivered. Doug Howard, CEO of Training Industry, predicted that:

Learning leaders will seek objective assessment of the training organization…. [They] will be conducting—using both internal and external resources—objective assessments of their training department readiness…. Companies that make the most of these assessments will be those that are most willing to open themselves to an honest evaluation (warts and all). (Howard 2010)

Understand the expectations of business executives. This is not about what training business executives need but, instead, what they expect from you—how you work with them, how you interact with their organizations, the services they value, how they expect you to deliver them, and the value expectations they have for the investments they are making. I have found that the list of expectations from senior business executives is not long, and they can articulate the list very crisply. But you have to ask. You have to engage them in a serious discussion on this topic. Understanding these expectations and asking for candid feedback about your performance will provide you with valuable information to evaluate where you are today and what you can improve in the future.

Manage your costs to acceptable levels and always consider the value you are delivering. Cost management will always be a priority for training organizations. But costs will be a more visible and serious issue when the value you are delivering is not evident. Having said that, we still need to be great stewards of the investment we receive from the business and we need to ensure that we are operating at an optimal cost level. Here are five critical actions managing costs effectively:

![]() Know how much your company is spending on training, where it is going, and what it is being spent on.

Know how much your company is spending on training, where it is going, and what it is being spent on.

![]() Continually look for opportunities to move fixed costs to variable costs. This is important because it allows us to pay for what we use, scale up and down without having to hire or fire, and eliminate the unpopular allocation model for spreading training costs.

Continually look for opportunities to move fixed costs to variable costs. This is important because it allows us to pay for what we use, scale up and down without having to hire or fire, and eliminate the unpopular allocation model for spreading training costs.

![]() Uncover the hidden training costs. For example, if you use outside providers, there are costs associated with each step in the procurement process. How much does it cost you to pay an invoice? How many invoices do you process in a month? How much time are your training professionals spending in the vendor procurement process? How many corporate resources are spending some part of their time doing training-related activities?

Uncover the hidden training costs. For example, if you use outside providers, there are costs associated with each step in the procurement process. How much does it cost you to pay an invoice? How many invoices do you process in a month? How much time are your training professionals spending in the vendor procurement process? How many corporate resources are spending some part of their time doing training-related activities?

![]() Take aggressive actions to reduce costs. Use outsourcing wherever possible because you will reap the benefits of your outsourcing provider’s best practice processes, ability to leverage resources, and off-shoring when possible.

Take aggressive actions to reduce costs. Use outsourcing wherever possible because you will reap the benefits of your outsourcing provider’s best practice processes, ability to leverage resources, and off-shoring when possible.

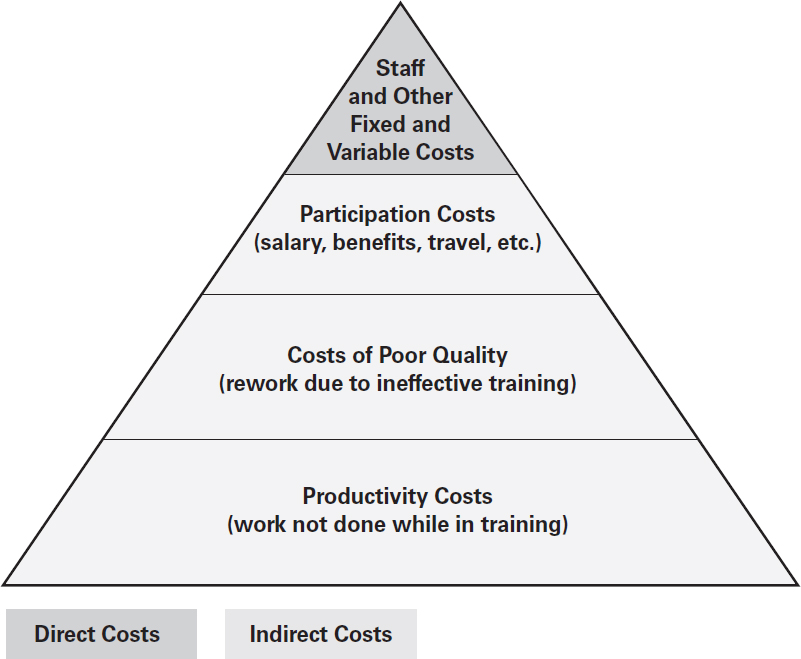

![]() Manage the total cost of training, not just the direct, out-of-pocket costs. Figure 4-1 illustrates the elements of total cost, most of which are often overlooked.

Manage the total cost of training, not just the direct, out-of-pocket costs. Figure 4-1 illustrates the elements of total cost, most of which are often overlooked.

Figure 4-1. Training Cost Model

My research has shown that the total cost of training is anywhere from three to five times more than the direct costs. That is significant because it offers many opportunities to reduce the hidden indirect costs and thus have a significant business impact. If you can reduce the length of a program or set of programs, you can reduce both delivery expense and participant labor costs associated with training. And by reducing the length of the training, you are returning people to their jobs sooner, which has a positive impact on productivity. Managing the total cost of training leads you to very different decisions than if you are just managing the direct costs. Training organizations should report on the total cost of training and the influence they are having on it in a timely basis. We should not be afraid to take credit for being effective stewards of organizational assets.

Training has characteristics that don’t support high fixed costs. Training is cyclical, as the demand for it ebbs and flows. While some of the work training organizations do remains predictable and consistent, like most businesses there are peaks and valleys. Staffing for the peaks is expensive and risky.

Training is far too often viewed as discretionary. In organizations in which training leaders have not presented a clear and compelling business case for their existence, training functions are one of the first to be asked to downsize in a challenging business environment.

Scalability is important. Because training demand can be variable, the best-managed organizations have the ability to scale up and down. This means having ready access to qualified training professionals who can quickly supplement the fixed staff when demand exceeds capacity, and being able to reduce resources when capacity exceeds demand.

Outsourcing

So far I have suggested that training organizations would be far better off if they shift from a highly fixed cost structure to one that is more flexible. As a result, outsourcing is a serious alternative for training leaders. But training leaders are still hesitant to treat it as a viable option; another thing that hasn’t changed during the past 16 years. Here are the five most common lies about outsourcing.

Lie #1: Outsourcing Can’t Reduce Costs

Talk about extremes. How can we be so far apart on the important issue of whether outsourcing can reduce costs? It is amazing that this debate continues. But perhaps it’s not a debate. Perhaps, at least from the training leaders’ side of the aisle, it’s more of a smokescreen.

In general, outsourcing has been shown to reduce costs across various functions, including information technology, human resources, and finance and accounting. For example, HR outsourcers are confident in their ability to reduce costs because the work they take on is mostly, if not completely, transactional, such as benefits administration and payroll processing (HR is estimated to be 70 percent transactional and 30 percent strategic), and it benefits from leverage, scale, and common processes and technologies. And outsourcing gets even better if the outsourcer can provide services to its clients using a variable cost model, so that the clients do not have to carry high fixed costs and can pay on a per-transaction basis for the services as they use them. Research reports and case studies on this are pretty consistent: Outsourcing reduces costs. While some outsourcing relationships have failed to meet expectations of cost reduction, quality improvement, and better control, industry experts and advisers would say that is the exception rather than the rule.

But here is the issue with training. Unlike these other transaction-heavy activities, training is roughly 30 percent transactional and 70 percent strategic, and unlike payroll, benefits, and other HR services, it is highly discretionary. So if cost reductions are the key driver, just stop training altogether or reduce the volume. As I suggested earlier, the key issue is that the investment–value equation for training is broken in many organizations, so any training outsourcing must be driven by the need to increase value.

Training outsourcers—particularly those who take on the transactional elements of training, such as technology, administration, and vendor management—can reduce the cost of these activities because they, like their counterparts in other functions, benefit from scale, leverage, and common technology and processes. Cost reduction is necessary, but it’s not sufficient. And while it might buy you some time, failure to address the value side of the equation will still leave you vulnerable to questions from business executives.

So back to the big question: Does training outsourcing reduce costs? The answer is that it does in transactional areas and it may in the more strategic areas, such as content development and delivery. Overall, the goal should be a reduction in the unit cost of training (the costs per person per hour, day, or year). In fact, when we dramatically improve the value of training, companies actually tend to spend more, not less.

Lie #2: No Outsider Can Know My Business Like I Do

Doubting the know-how of outsiders is another objection raised by internal training resources. Outsourcing does not mean that you stop accessing the subject matter expertise of your businesses. It means that you start accessing resources that are professional, skilled, trained, experienced, and best-in-class in doing what they do. Companies have been outsourcing or out-tasking various parts of training for years, particularly to gain access to content. That is why there is such a huge market for training companies. These companies work with their customers, both training professionals and subject matter experts, to put together learning solutions that directly address business needs. These companies understand how to design, develop, and deliver training, and they apply those capabilities to the subject matter or business issues at hand. Even the skeptics who say, “no outsider can know my business like I do,” frequently tap into these providers for help.

Training outsourcers possess the same capabilities as internal training organizations. Not only do they have access to training expertise, they understand processes, operations, and technology. They integrate these capabilities to serve their customers. I would argue that the only proprietary aspect of any business is the subject matter. All the surrounding training processes—design, development, delivery, technology, administration, vendor management, and others—are fairly generic and certainly aren’t compromised by the outsourcing provider “not knowing your business.”

Lie #3: Strategic Activities Can’t Be Outsourced

Training leaders—and training outsourcers who don’t offer the services and thus argue that they should not be outsourced—perpetuate the myth that strategic activities can’t be outsourced. The most strategic of training activities is understanding the business’s direction, strategy, challenges, issues, objectives, and goals, and then determining how and where training can add value. Some people call this activity performance consulting; I prefer relationship management. Relationship managers understand their customer’s business, live inside the business, sit at the business table, look for ways in which their work can make a difference, and bring broad business insights to their customers. They understand when training can help and when it can’t. They don’t ask businesspeople: “What training do you need?” Instead, they talk about what the sales or market share or productivity improvement objectives are and present options for advancing them through training, performance support, or any other service a highly skilled training organization can provide.

Several years ago I did a training outsourcing deal in which my customer wanted to retain the relationship management role. We set up the operational process so that the customer’s employees would work with their internal clients and then work with my company to deliver solutions. Within short order, the training leader for this company received calls from senior business leaders demanding to know: “What’s new about this? These are the same people who have not served my business well in the past. You promised me transformation with this outsourcing initiative, not more of the same!” Suffice it to say, the training leader acted quickly and added this work to the contract. My firm brought in a team that was highly skilled in this type of business consulting. The training leader changed his approach, and the business benefited.

It is understandable why internal training employees might argue against outsourcing this part of the training value chain. But why do so many training outsourcers agree? There are two major reasons: First, they see their business as transactional, not transformational. As a result, they don’t have a service offering that extends across the entire training value chain. Instead, they focus solely on the transactional elements. And second, they don’t want to create conflict with a potential client for fear of losing their chance at the opportunity. Isn’t the client always right? But providers who always agree with you are not providing the kind of insight, expertise, and know-how that you are paying for and that you deserve.

Lie #4: People Don’t Lose Their Jobs After Outsourcing

I have been on many panels with outsourcing providers that say that training professionals don’t lose their jobs in an outsourcing model. We need to stop sugarcoating this. The entry point for most training outsourcers is cost reduction, and most research indicates that the primary reason to outsource is to reduce operating costs. It is hard to reduce costs without eliminating jobs. It is that simple. Outsourcers who are not explicit about this are either ignoring the issue or being less than truthful. I hasten to add that if cost is, in fact, an issue and you don’t outsource, it is likely that jobs will still be lost, but the numbers may be higher.

Lie #5: Outsourcing Means Losing Control

The idea that outsourcing means losing control couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, I would contend that you really don’t have control now. In many organizations, training continues to be one of the largest unmanaged expenses. Training is pervasive. It happens everywhere. And most of the costs occur outside HR. Organizations have multiple systems, processes, and people engaged in the design, development, and delivery of training. But very few organizations know how much they are really spending, and, as a result, they have little control over the investment.

If you outsource in a comprehensive way, you should work with your partner to identify how much is being spent; where it is being spent; what processes, technology, and people are being used; where duplication and redundancy exist; and so on. And when your partner works with you to manage all aspects of the training value chain in an integrated way, your company will have a single point of accountability with service-level agreements, management of costs and quality, and, most important, control.

On both sides of the outsourcing table, I have seen control increase dramatically through the process. And that holds true regardless of the scope of the outsourcing arrangement. Being able to look to a single point of control for accountability, metrics, responsibility, and costs is a significant benefit of the outsourcing decision.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have attempted to address many of the lies, myths, and beliefs about managing the learning function. I have discussed some misconceptions about outsourcing, the need to focus on efficiency and effectiveness, how to gain control over the training value chain, and how and why we must think about managing the training function like it is a business. Our measures should be related to the business of training and the work of training. Customer retention, cycle time, quality, costs, and customer expectations are as important as the first three levels of the Kirkpatrick measurement model. And at the end of the day, the only true measure is the business value your customer receives from the investment in you. That is what businesses worry about, and that is what training professionals at all levels should fixate on. Our success, as with any business, should be measured by the success of our customers. And always remember, it’s not about training; it’s about results.

References

CorpU. 2011. Running Training Like a Business: 2011 Research Update. Mechanicsburg, PA: CorpU.

Howard, D. 2010. “10 Predictions for 2010: Will It Be the Year for Real Change?” Training Industry, January 12. www.trainingindustry.com/articles/10-predictions-for-2010.aspx.

PwC. 2012. Delivering Results: Growth and Value in a Volatile World (15th Annual Global CEO Survey 2012). www.pwc.com/gx/en/ceo-survey/pdf/15th-global-pwc-ceo-survey.pdf.

van Adelsberg, D., and E.A. Trolley. 1999. Running Training Like a Business. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.