6

Lies About Learning Strategies

Tina Busch

We all know the learning strategies, and leaders who implement them, that succeed and those that fail. There are plenty of good articles, books, and whitepapers with blueprints on how to build an effective learning strategy and how not to. And so with all the resources available, why do so many still get it wrong? Why are those who get it right able to replicate it across different companies and industries, under widely varying conditions?

First, let’s step back and start with what learning strategy is and isn’t. In this chapter, I use “learning strategy” not as instructional strategy or how we deliver or teach content, but rather as competitive strategy or how learning organizations make their companies more successful in the marketplace and how they operate as a strategic lever to achieve their desired business results. All businesses aim to achieve a competitive advantage—to acquire market share, accumulate customers, and win the war on talent. And no corporate organization does this without a learning strategy. Consider the questions required to win in business:

![]() What is the organizational vision?

What is the organizational vision?

![]() Who are our customers and markets?

Who are our customers and markets?

![]() What goods and services do we provide?

What goods and services do we provide?

![]() Who are the people and what is the culture we need to get us there?

Who are the people and what is the culture we need to get us there?

![]() What technology, systems, or procedures are required to support the vision?

What technology, systems, or procedures are required to support the vision?

![]() How do we manage for the present and future win?

How do we manage for the present and future win?

![]() What is our leadership style?

What is our leadership style?

Businesses require the right people, and a successful learning strategy helps these people deliver and succeed based on the answers to the questions above.

Peter Drucker, referred to by Businessweek as “the man who invented management” once said, “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer.” If it were that simple, though, why doesn’t every business win? Why doesn’t every learning organization simply align to the business strategy and deliver? Why are learning professionals still talking about how to earn a seat at the table? In looking back over my career and talking to learning leaders about their experiences, there appears to be a pattern—a recipe for success or failure—and the recipe is not just for learning leaders, but also for leadership and business strategy in general. An organization’s most vital competitive advantage is its people. It can have the best products, the best services, and the best infrastructure, but if it lacks the right people and learning strategies the organization will, eventually, lose its competitive advantage.

The strategies that fail almost always share a common trait. Despite looking good on paper and following best practice, they lack an understanding of and consideration for the complex aspects of any strategy: people and culture. They too often underestimate the importance of answering “Who are the people and what is the culture we need to get us where we want to be?”

Why does this happen, especially when we are in the people business? The answer is because we succumb to the lies we are told—and lies we tell ourselves—about what it takes to create a successful learning organization and to be a successful learning leader. And although I will suggest that we must, at times, forget about the softer or people side of strategy, it is those very people who will judge the effectiveness of our strategies and, possibly, the viability of our careers. In this chapter, I’ll describe the five lies that I believe have the biggest impact on the development of effective learning strategies and offer approaches for avoiding them.

Lie #1: Data Are More Important Than Feelings

As learning leaders, we focus a lot on processes, frameworks, metrics, and data—for good reasons. They are fundamental to formulating strategies for how to run our business. But how often do we factor in our customer’s feelings and the power of human behavior?

In 2010, Gap launched a new logo to refresh its image and appeal to a hipper, younger crowd. But the company lost sight of its target market—people who want the basics and aren’t interested in trendy styles. Loyal customers felt disconnected from the new brand, and the logo failed to resonate with the new target audience. Gap’s mistake was not in wanting to change and evolve, but in not being in touch with its customers’ personas to ensure that the new brand strategy would connect. How does this happen?

You would expect that before implementing such a large change, Gap had analyzed data, held customer focus groups, and considered current and future trends. Lots of smart, hardworking people created and implemented this new logo, right? Perspectives on why “Gapgate” happened tended to focus on the logo itself—the font was too bland, the new image looked like child’s clipart, and so on. But that wasn’t the real problem. Despite having talented designers and marketers behind the launch, Gap debuted the new logo on its website without explaining the rebrand—without first understanding how its loyal customers felt about the original logo.

Much like the Gap logo debacle, learning leaders too often implement an agenda without first understanding the behavior, wants, and needs of their customers. We do this because while data may allow us to predict what a customer will purchase, no amount of quantitative data will tell us exactly why they do so. In formulating strategy, we need to not only understand the data but also take the time to determine what makes our customers tick. In other words, a successful learning strategy requires the learning leader to systematically study the people and culture in the organization. Otherwise known as ethnography, this method is used primarily by anthropologists. Thus a successful learning leader needs to be part businessperson (gathering data and using the models, frameworks, and processes in your arsenal) and part anthropologist (becoming immersed in the objective observation of the people and culture you seek to influence). And it’s often what you learn as an anthropologist that drives a successful learning strategy—or one that fails.

So, how do you do this? In The Moment of Clarity (2014), Christian Madsbjerg and Mikkel Rasmussen outline a human science process called sensemaking, which simply and elegantly provides steps to observe our customers and their experiences in a business setting. The process follows five steps:

1. Reframe the problem. First, reframe a business problem in terms of the human experience or a phenomenon. To do so, shift the perspective from how the business sees the problem to how the customer sees it.

2. Collect the data. Thinking and acting like an anthropologist means collecting data in a way that might be very different from the norm. These data are not coming from surveys or scripted focus groups. Instead, engage in the lives of your customers with no preconceived notions or assumptions, while observing and collecting information. What might this look like? Sit with a business unit, region, or function for a few days. Or have lunch with your program participants.

3. Look for patterns. Once you have collected the data, look for patterns, connect the dots, and find any common themes.

4. Create the key insights. This is where the learning function can become a strategic lever for the business. Find the gaps between the business assumptions and customers’ experiences; that’s where innovation occurs. What do the patterns tell you?

5. Build the business impact. Build value by translating your insights into initiatives within your strategy.

Sure, it’s harder to quantify, but going through the ethnography process does more than create a new lens through which to think about and solve business problems. Unraveling the reasons behind customer decisions gives the customers a voice, and they will speak out loudly when their sensibilities are offended or, worse, not even considered. Gap experienced this firsthand within minutes of revealing the new logo on its website.

Lie #2: I Have Years of Education and Experience, I Know Best

Imagine that a foreign exchange student sits at the first meal with his new host family and tells them that what they eat and how they eat is all wrong. He then clears the table and resets it with the latest cutlery and cuisine from his country, the greatest in the world he tells them. The family is embarrassed by their struggle to use the new tools for eating the meal. The food, with its new smells, tastes, and textures, while interesting, causes considerable anxiety due to the vast differences. And the family is offended because the foreign student assumed their customs were wrong and undesirable.

Who would do that? Well, learning leaders do it every day. When we get a new assignment, we are like the foreign exchange student sitting with a host family—our customers. We often speak a different language, use our own tools and frameworks, and expect everyone to just go along because we said they should.

Having an ego and pushing an agenda without understanding or respecting the local culture will lead to failure every time. I once witnessed a learning leader join a global company and implement a one-size-fits-all strategy that was trendy at the time: Migrate all classroom learning to computer-based training. Knowing that the organization was in a cost-savings mode, he thought he could gain a quick win by moving to what seemed to be a more cost-effective learning model. However, what might have worked at a startup company in the high-tech industry with a younger employee base was not the right strategy for a century-old manufacturing organization comprising mostly baby boomers dispersed over 60 countries. He was quickly judged as being neither customer-centric nor inclusive. His customers thought that they had no voice and were being force-fed something they didn’t understand or care to consume. So he was gone within a year, simply because he applied a strategy that seemed to make sense on paper and for the balance sheet, but didn’t consider the organization’s people and culture.

Despite years of experience and education, learning leaders often fail because they assume they know best. Showing arrogance, lacking stakeholder analysis, and not devoting enough energy to building social capital (the quantity and quality of relationships) and emotional capital (the ability to understand and leverage human behavior) will doom many a strategy. Showing respect and consideration for an organization’s history and its people is critical to a successful learning strategy.

Lie #3: ADDIE Is Only for Instructional Design

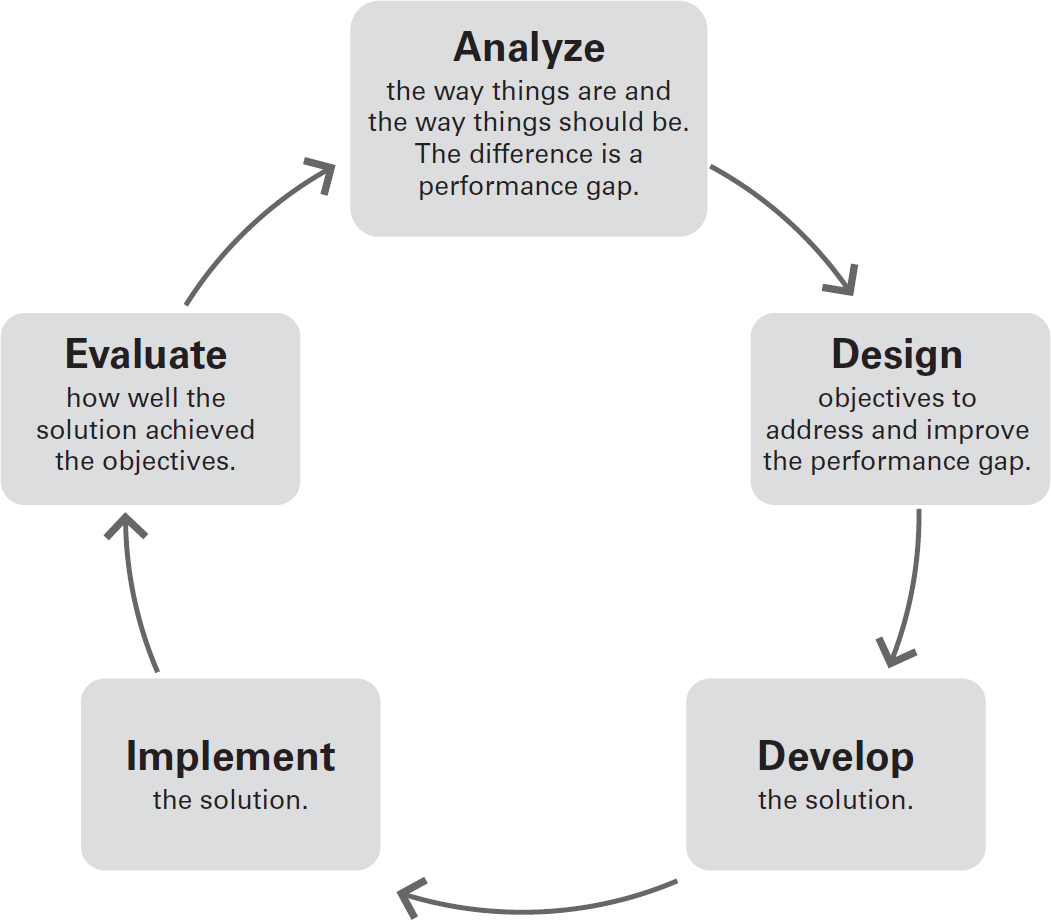

Attention learning leaders—you already have the secret to creating good learning strategy in your arsenal: the ADDIE instructional design model, or any other instructional system design or performance improvement model for that matter. While some models may be considered more agile or less linear, they all have similar structures to analyze, design, and do it. Let’s take a look, using ADDIE as a road map for learning strategy design (Figure 6-1).

Figure 6-1. The ADDIE Model

Analyze. Far too often, a learning strategy is designed, developed, implemented, and evaluated before a thorough current state analysis or needs assessment occurs. Analysis is not just about gathering the information to create a sound strategy. When done well, it allows you to build the network and relationships that will ensure stakeholder buy-in and successful implementation. During analysis, learning leaders should aim to thoroughly understand the way things happen today (the current state) and the preferred way (the desired or future state). Any differences represent opportunities for change or improvement (performance gaps).

Key questions for the analyze phase include:

![]() What are the current and future needs of the different business units, functions, and organization as a whole?

What are the current and future needs of the different business units, functions, and organization as a whole?

![]() What is the current state of learning?

What is the current state of learning?

![]() What works well and what needs change?

What works well and what needs change?

![]() Who is your audience?

Who is your audience?

![]() In what environment (culture, technology) does your audience operate?

In what environment (culture, technology) does your audience operate?

Anyone familiar with instructional design knows that many more questions can be asked during analysis, and answering the ones above alone can be overwhelming, given the amount of data you might gather. Regardless, the next step is to synthesize. Very similar to the steps outlined in the sensemaking or ethnography process, you should next look for patterns and create insights, which will set you up for success during design.

Design. When designing the learning strategy, you should create objectives to address and, in the best possible world, eliminate performance gaps in the organization, building on what you learned during analysis. You should develop a learning philosophy, learning vision, and learning objectives, and judge how they will inform the structure, governance, and guiding principles for your learning strategy and the organization you create as a result.

Key questions for the design phase include:

![]() What are we trying to accomplish with a learning strategy?

What are we trying to accomplish with a learning strategy?

![]() How does it align with the business strategy?

How does it align with the business strategy?

![]() What does it mean for individual contributors, managers, and senior leaders?

What does it mean for individual contributors, managers, and senior leaders?

![]() How does it integrate with other key human resource and talent development initiatives?

How does it integrate with other key human resource and talent development initiatives?

![]() What does this vision suggest for the organization structure?

What does this vision suggest for the organization structure?

![]() Who are the learning and development staff and what work will they do?

Who are the learning and development staff and what work will they do?

![]() What kind of governance is required to meet the vision and objectives?

What kind of governance is required to meet the vision and objectives?

![]() What should be centralized or decentralized to better meet the needs of organization?

What should be centralized or decentralized to better meet the needs of organization?

With the analysis and design complete, you have a blueprint for building a strategy that aligns with your customers’ needs. It’s time to develop.

Develop. When developing solutions, primary products and services, selection criteria, content delivery, outsourcing, and primary funding sources are the key elements of a learning strategy to consider.

Key questions for the develop phase include:

![]() What products and services are needed in the learning organization to support the business strategy?

What products and services are needed in the learning organization to support the business strategy?

![]() Who can use the learning products or services? Who receives what?

Who can use the learning products or services? Who receives what?

![]() What’s mandatory versus recommended?

What’s mandatory versus recommended?

![]() How and where is training delivered?

How and where is training delivered?

![]() How does the way content is delivered differ for technical, compliance, soft skills, or other types of training?

How does the way content is delivered differ for technical, compliance, soft skills, or other types of training?

![]() What aspects of learning are appropriate to outsource?

What aspects of learning are appropriate to outsource?

![]() How will we manage vendors?

How will we manage vendors?

![]() How are the services paid for?

How are the services paid for?

![]() Who creates, makes decisions, and monitors the overall budget?

Who creates, makes decisions, and monitors the overall budget?

Implement. As the learning leader implements the solutions, there must be a strategy to promote, distribute, report, and maintain them.

Key questions for the implement phase include:

![]() Will implementation be enterprise-wide or local?

Will implementation be enterprise-wide or local?

![]() What are the requirements for a common system?

What are the requirements for a common system?

![]() Who owns or tracks product and service use?

Who owns or tracks product and service use?

![]() How are programs promoted?

How are programs promoted?

Evaluate. We’ve all heard the phrase “run training like a business.” How we hold ourselves accountable for our results is a key indicator of the level of business orientation in the learning operation. Evaluation should include both operational and performance indicators so that efficiency and effectiveness are measured.

Key questions for the evaluate phase include:

![]() What are our success indicators?

What are our success indicators?

![]() How is efficiency and effectiveness measured?

How is efficiency and effectiveness measured?

![]() Who owns or receives reports?

Who owns or receives reports?

Consider conducting quarterly operational reviews with your primary stakeholders. Rarely will a learning leader be expected to conduct such a review, so you may have to ask for it. But this is not a bad thing, because it demonstrates to business leaders that you understand the role that learning plays in organizational success. During these reviews, share your metrics and ensure that you and the business leadership are aligned on what success looks like.

In this section, I intended to show how to use ADDIE to develop your learning strategy. This alone will not bring successful implementation. You’ll also need to sell your strategy to the organization. See the next two lies for tips on positioning a learning strategy for acceptance by your customers.

Lie #4: Complex Organizations Require Complex Learning Strategies

Complex organizations don’t require complex learning strategies. Why? Well, strategies must be embraced by stakeholders, and complex doesn’t always mean better. For a learning organization to succeed, it must position itself as a strategic partner that helps deliver on the company’s goals. In other words, run training as the business it is.

I like to express a learning strategy in the framework of a simplistic business model: producing products and services with a means (infrastructure) to transfer or sell it to your customers. The currencies we operate with are human and political capital—unless you happen to have a P&L for learning, which some organizations do. Using the term sell might sound like we’re in a transactional business, and while there will always be an element of transactions in most businesses, learning organizations need to evolve from being transaction oriented to solution oriented. We are, after all, in the business of selling solutions.

Figure 6-2 is a three-tiered learning strategy, which, like most simple business models, has a portfolio of products and services that are deployed and managed through an infrastructure—think operations and supply chain. At the center are the customers or consumers. What follows is a case study that illustrates how this model has been deployed successfully.

Figure 6-2. Learning Strategy Model

In 2010, a global consumer packaged goods company completed a human resource transformation, which included learning and development. In the past, learning and development in the company was global in name only. The department served primarily North America and was not scalable. The team performed mainly transactional work. The portfolio was not aligned to the business, and awareness and credibility were low. It was time for a change. The department performed a needs assessment, reviewing employee engagement surveys and conducting interviews with customers and stakeholders. The strategy used to transform learning and development followed the three tiers in Figure 6-2: services, portfolio, and infrastructure.

Services. The learning and development team had a credibility issue and perceived value was low. Awareness and use was mainly in North America, focused on transactional work such as program management and facilitation. Transactions (such as learning events) occurred, but solutions to business problems weren’t provided. While a few programs generated positive reviews, none of the business leaders believed the learning organization was a strategic lever for business results.

Needing to demonstrate strategic value, the team created a new role—performance consultant. Consultants capable of working within the highly complex organization and implementing solutions that could improve individual and team performance were aligned to each of the company’s business units and functional groups. Responsible for partnering with business and human resource leaders, conducting needs assessments, and identifying and implementing performance improvement solutions, these consultants made up a newly formed services division in the learning organization.

Portfolio. The existing portfolio of learning products was not aligned to the business and served only a small segment of the company’s U.S. population. Needing to stretch the budget to reach more employees with relevant content, portfolio managers worked with the performance consultants to identify the common skills gaps. Partnering with procurement, the portfolio managers sourced content providers who could support a global population in the prioritized areas. And creating several strategic vendor partnerships, the company had its first fully aligned global portfolio of learning content.

Infrastructure. The company then needed the technical infrastructure to help manage the portfolio and market its products and services. The current learning management system was outdated, available to North America only, and used only partly by the organization to which it was available. A global learning council of learning and talent representatives from all regions, businesses, and functions was formed to identify what the new learning management system would need to support the organization’s diverse needs.

After implementation, the new system gained immediate buy-in from the learning and talent representatives because they were part of the decision-making process. Involving the learning and talent representatives was critical because they were the ones who decided if, and how, the new system would be used, and they were the champions of the system to customers. In other words, regardless of their level in the organization, these representatives were key decision makers and change agents.

Customers. Customers are the center of the learning strategy. The services, portfolio, and infrastructure were all developed with the customers’ needs in mind.

Your strategy is your vision. The learning strategy this company used was simple in structure, although it was executed in a highly complex environment. In the end, a simple strategy is easier to sell, both to customers and stakeholders.

Lie #5: I’m a Learning Professional, Not a Salesperson

Leadership is all about selling, and the best learning professionals are selling every day. They are highly skilled in many of the same competencies required to be a great salesperson, such as communicating a vision, building and maintaining relationships, inspiring confidence, influencing and persuading, and managing change. Let’s take a closer look at these competencies and how they might apply to learning.

Communicating a vision and goals. You may think you are selling the products, services, and infrastructure that make up the strategy, but you’re actually communicating the vision of what the strategy will do for the organization and how it will make people feel. To do so effectively, learning leaders must excel at verbal and written communication and exude an executive presence.

Building and maintaining relationships. Ensuring that the product or service aligns with the customers’ needs and thus resonates with them can help you build and maintain professional customer relationships. When decision making takes a customer-oriented perspective, the work will be easier and far more rewarding.

Inspiring confidence. Since we can’t make our customers simply accept our vision and strategy, we have to inspire in them confidence to do so.

Influencing and persuading. Your ability to connect with people emotionally and convince them of the value and appropriateness of your vision and strategy is what will ultimately drive success.

Managing change. If no one buys, nothing changes. If no one follows, leadership is lacking. Learning professionals are in the change business, and selling change requires great relationship management, influence, and persuasion. Learning professionals are salespeople, and, more specifically, great learning professionals are great salespeople.

Figure 6-3 illustrates a simple sales process. You will recognize several of the ADDIE elements in it, but it also includes some stakeholder management steps, such as establishing the relationships, presenting the solution, and negotiating or closing the sale.

Figure 6-3. Sales Process Model

One selling skill to remember is to not put the sale first. If your stakeholders or customers suspect you are putting the sale before their interests (or driving your own agenda), the relationship suffers, and you won’t make the sale anyway.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explored five lies that separate the good learning strategies from the bad. A common theme is that they all have people and culture interdependencies. Lies #1 (data are more important than feelings) and #2 (I have years of education and experience, I know best) provided tips to success in designing learning strategies: Consider the what (data) and why (feelings) in your analysis; respect and consider the organization’s history and culture. Your experience and education loses value if you can’t connect with your customers.

Lie #3 (ADDIE is only for instructional design) recommends using ADDIE, a familiar tool, in designing the learning strategy. With people and culture components embedded throughout the model, it can help you break down the design process. Lie #4 (complex organizations require complex learning strategies) is also about design, and the reminder to keep it simple. Complex strategies are hard to sell and often unnecessary.

And finally Lie #5 (I’m a learning professional, not a salesperson) may be the most important and most difficult. A design is only as good as its ability to get sold, and that takes strong leadership.

At the center of each of these lies is the customer—the secret to success. Learning leaders who keep their customers close in mind while developing strategies from analysis through implementation increase their chances of success.

Reference

Madsbjerg, C., and M. Rasmussen. 2014. The Moment of Clarity. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Recommended Reading

Carnegie, D. 1981. How to Win Friends and Influence People. Rev. ed. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Conrad, D. 2011. “Great Leaders Are Great Salespeople.” Strategic Leadership Review 1(2): 9–15.

Dick, W., and L. Carey. 1996. The Systematic Design of Instruction. 4th ed. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers.

Eikenberry, K. 2010. “Five Reasons Why Every Leader Is a Salesperson.” Leadership & Learning (blog), August 23. http://blog.kevineikenberry.com/leadership/five-reasons-why-every-leader-is-a-salesperson.