Chapter 1. Reactive programming

- Being reactive

- Thinking about events as streams

- Introducing Reactive Extensions (Rx)

The reactive programming paradigm has gained increasing popularity in recent years as a model that aims to simplify the implementation of event-driven applications and the execution of asynchronous code. Reactive programming concentrates on the propagation of changes and their effects—simply put, how to react to changes and create data flows that depend on them.[1]

This book is about reactive programming and not about functional reactive programming (FRP). FRP can operate on continuous time, whereas Rx can operate only on discrete points of time. More info can be found at the FRP creator’s keynote, http://mng.bz/TcB6.

With the rise of applications such as Facebook and Twitter, every change happening on one side of the ocean (for example, a status update) is immediately observed on the other side, and a chain of reactions occurs instantly inside the application. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a simplified model to express this reaction chain is needed. Today, modern applications are highly driven by changes happening in the outside environment (such as in GPS location, battery and power management, and social networking messages) as well as by changes inside the application (such as web call responses, file reading and writing, and timers). To all of those events, the applications are reacting accordingly—for instance, by changing the displayed view or modifying stored data.

We see the necessity for a simplified model for reacting to events in many types of applications: robotics, mobile apps, health care, and more. Reacting to events in a classic imperative way leads to cumbersome, hard-to-understand, and error-prone code, because the poor programmer who is responsible for coordinating events and data changes has to work manually with isolated islands of code that can change that same data. These changes might happen in an unpredictable order or even at the same time. Reactive programming provides abstractions to events and to states that change over time so that we can free ourselves from managing the dependencies between those values when we create the chains of execution that run when those events occur.

Reactive Extensions (Rx) is a library that provides the reactive programming model for .NET applications. Rx makes event-handling code simpler and more expressive by using declarative operations (in LINQ style) to create queries over a single sequence of events. Rx also provides methods called combinators (combining operations) that enable you to join sequences of events in order to handle patterns of event occurrences or the correlations between them. At the time of this writing, more than 600 operations (with overloads) are in the Rx library. Each one encapsulates recurring event-processing code that otherwise you’d have to write yourself.

This book’s purpose is to teach you why you should embrace the reactive programming way of thinking and how to use Rx to build event-driven applications with ease and, most important, fun. The book will teach you step by step about the various layers that Rx is built upon, from the building blocks that allow you to create reactive data and event streams, through the rich query capabilities that Rx provides, and the Rx concurrency model that allows you to control the asynchronicity of your code and the processing of your reactive handlers. But first you need to understand what being reactive means, and the difference between traditional imperative programming and the reactive way of working with events.

1.1. Being reactive

As changes happen in an application, your code needs to react to them; that’s what being reactive means. Changes come in many forms. The simplest one is a change of a variable value that we’re so accustomed to in our day-to-day programming. The variable holds a value that can be changed at a particular time by a certain operation. For instance, in C# you can write something like this:

int a = 2;

int b = 3;

int c = a + b;

Console.WriteLine("before: the value of c is {0}",c);

a=7;

b=2;

Console.WriteLine("after: the value of c is {0}",c);

before: the value of c is 5 after: the value of c is 5

In this small program, both printouts show the same value for the c variable. In our imperative programming model, the value of c is 5, and it will stay 5 unless you override it explicitly.

Sometimes you want c to be updated the moment a or b changes. Reactive programming introduces a different type of variable that’s time varying: this variable isn’t fixed to its assigned value, but rather the value varies by reacting to changes that happen over time.

Look again at our little program; when it’s running in a reactive programming model, the output is

before: the value of c is 5 after: the value of c is 9

“Magically” the value of c has changed. This is due to the change that happened to its dependencies. This process works just like a machine that’s fed from two parallel conveyers and produces an item from the input on either side, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. A reactive representation of the function c = a + b. As the values of a and b are changing, c’s value is changing as well. When a is 7 and b is 2, c automatically changes to 9. When b changes to 1, c becomes 8 because a’s value is still 7.

You might find it surprising, but you’ve probably worked with reactive applications for years. This concept of reactiveness is what makes your favorite spreadsheet application so easy and fun to use. When you create this type of equation in a spreadsheet cell, each time you change the value in cells that feed into the equation, the result in the final cell changes automatically.

1.1.1. Reactiveness in your application

In a real-world application, you can spot possible time-variant variables in many circumstances—for instance, GPS location, temperature, mouse coordinates, or even text-box content. All of these hold a value that’s changing over time, to which the application reacts, and are, therefore, time variant. It’s also worth mentioning that time itself is a time variant; its value is changing all the time. In an imperative programming model such as C#, you’d use events to create the mechanism of reacting to change, but that can lead to hard-to-maintain code because events are scattered among various code fragments.

Imagine a mobile application that helps users find discounts and specials in shops located in their surrounding area. Let’s call it Shoppy. Figure 1.2 describes the Shoppy architecture.

Figure 1.2. The Shoppy application architecture. The mobile app receives the current location from the GPS and can query about shops and deals via the application service. When a new deal is available, the application service sends a push notification through the push notifications server.

One of the great features you want from Shoppy is to make the size of the shop icon bigger on the map as the user gets closer (from a certain minimal radius), as shown in figure 1.3. You also want the system to push new deals to the application when updates are available.

Figure 1.3. The Shoppy application view of the map. When the user is far from the Rx shop, the icon is small (on the left), and as the user gets closer, the icon gets bigger (on the right).

In this scenario, you could say that the store.Location, myLocation, and iconSize variables are time variant. For each store, the icon size could be written:

distance = store.Location – myLocation; iconSize = (MINIMAL_RADIUS / distance)*MinIconSize

Because you’ve used time-variant variables, each time a change occurs in the my-Location variable, a change is triggered in the distance variable. The application will eventually react by making the store icon appear bigger or smaller, depending on the distance from the store. Note that for simplicity, I didn’t handle the boundary check on the minimum allowed icon size, and that distance might be 0 or close to it.

This is a simple example, but as you’ll see, the great power of using the reactive programming model lies in its ability to combine and join, as well as to partition and split the stream of values that each time-variant variable is pushing. This is because reactive programming lets you focus on what you’re trying to achieve rather than on the technical details of making it work. This leads to simple and readable code and eliminates most boilerplate code (such as change tracking or state management) that distracts you from the intent of your code logic. When the code is short and focused, it’s less buggy and easier to grasp.

We can now stop talking theoretically so you can see how to bring reactive programming into action in .NET with the help of Rx.

1.2. Introducing Reactive Extensions

Now that we’ve covered reactive programming, it’s time to get to know our star: Reactive Extensions, which is often shortened to Rx. Microsoft developed the Reactive Extensions library to make it easy to work with streams of events and data. In a way, a time-variant value is by itself a stream of events; each value change is a type of event that you subscribe to and that updates the values that depend on it.

Rx facilitates working with streams of events by abstracting them as observable sequences, which is also the way Rx represents time-variant values. Observable means that you as a user can observe the values that the sequence carries, and sequence means an order exists to what’s carried. Rx was architected by Erik Meijer and Brian Beckman and drew its inspiration from the functional programming style. In Rx, a stream is represented by observables that you can create from .NET events, tasks, or collections, or can create by yourself from another source. Using Rx, you can query the observables with LINQ operators and control the concurrency with schedulers;[2] that’s why Rx is often defined in the Rx.NET sources as Rx = Observables + LINQ + Schedulers.[3] The layers of Rx.NET are shown in figure 1.4.

A scheduler is a unit that holds an internal clock and is used to determine when and where (thread, task, and even machine) notifications are emitted.

Reactive-Extensions/Rx.Net github repository, https://github.com/Reactive-Extensions/Rx.NET.

Figure 1.4. The Rx layers. In the middle are the key interfaces that represent event streams and on the bottom are the schedulers that control the concurrency of the stream processing. Above all is the powerful operators library that enables you to create an event-processing pipeline in LINQ style.

You’ll explore each component of the Rx layers as well as their interactions throughout this book, but first let’s look at a short history of Rx origins.

1.2.1. Rx history

I believe that to get full control of something (especially technology), you should know the history and the details behind the scenes. Let’s start with the Rx logo which features an electric eel, shown in figure 1.5; this eel was Microsoft Live Labs’ Volta project logo.

Figure 1.5. The Rx electric eel logo, inspired from the Volta project

The Volta project was an experimental developer toolset for creating multitier applications for the cloud, before the term cloud was formally defined. Using Volta, you could specify which portion of your application needed to run in the cloud (server) and which on the client (desktop, JavaScript, or Silverlight), and the Volta compiler would do the hard work for you. Soon it became apparent that a gap existed in transferring events arising from the server to the clients. Because .NET events aren’t first-class citizens, they couldn’t be serialized and pushed to the clients, so the observable and observer pair was formed (though it wasn’t called that at the time).

Rx isn’t the only technology that came out of project Volta. An intermediate language (IL) to the JavaScript compiler was also invented and is the origin of Microsoft TypeScript. The same team that worked on Volta is the one that brought Rx to life.

Since its release in 2010, Rx has been a success story that’s been adopted by many companies. Its success was seen in other communities outside .NET, and it was soon being ported to other languages and technologies. Netflix, for example, uses Rx extensively in its service layer and is responsible for the RxJava port.[4] Microsoft also uses Rx internally to run Cortana—the intelligent personal assistant that’s hosted inside every Windows Phone device; when you create an event, an observable is created in the background.

See “Reactive Programming in the Netflix API with RxJava” by Ben Christensen and Jafar Husain (http://techblog.netflix.com/2013/02/rxjava-netflix-api.html) for details.

At the time of this writing, Rx is supported in more than 10 languages, including JavaScript, C++, Python, and Swift. Reactive Extensions is now a collection of open source projects. You can find information about them as well as documentation and news at http://reactivex.io/. Reactive Extensions for .NET is hosted under the GitHub repo at https://github.com/Reactive-Extensions/Rx.NET.

Now that we’ve covered a bit of the history and survived to tell about it, let’s start exploring the Rx internals.

1.2.2. Rx on the client and server

Rx is a good fit with event-driven applications. This makes sense because events (as you saw earlier) are the imperative way to create time-variant values. Historically, event-driven programming was seen mainly in client-side technologies because of the user interaction that was implemented as events. For example, you may have worked with OnMouseMove or OnKeyPressed events. For that reason, it’s no wonder that you see many client applications using Rx. Furthermore, some client frameworks are based on Rx, such as ReactiveUI (http://reactiveui.net).

But let me assure you that Rx isn’t client-side-only technology. On the contrary, many scenarios exist for server-side code that Rx will fit perfectly. In addition, as I said before, Rx is used for large applications such as Microsoft Cortana, Netflix, and complex event processing (CEP) using Microsoft StreamInsight. Rx is an excellent library for dealing with messages that the application receives, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s running on a service layer or a client layer.

1.2.3. Observables

Observables are used to implement time-variant values (which we defined as observable sequences) in Rx. They represent the push model, in which new data is pushed to (or notifies) the observers.

Observables are defined as the source of the events (or notifications) or, if you prefer, the publishers of a stream of data. And the push model means that instead of having the observers fetch data from the source and always checking whether there’s new data that wasn’t already taken (the pull model), the data is delivered to the observers when it’s available.

Observables implement the IObservable<T> interface that has resided in the System namespace since version 4.0 of the .NET Framework.

Listing 1.1. The IObservable interface

The IObservable<T> interface has only one method, Subscribe, that allows observers to be subscribed for notifications. The Subscribe method returns an IDisposable object that represents the subscription and allows the observer to unsubscribe at any time by calling the Dispose method. Observables hold the collection of subscribed observers and notify them when there’s something worth notifying. This is done using the IObserver<T> interface, which also has resided in the System namespace since version 4.0 of the .NET Framework, as shown here.

Listing 1.2. The IObserver interface

The basic flow of using IObservable and IObserver is shown in figure 1.6. Observables don’t always complete; they can be providers of a potentially unbounded number of sequenced elements (such as an infinite collection). An observable also can be “quiet,” meaning it never pushed any element and never will. Observables can also fail; the failure can occur after the observable has already pushed elements or it can happen without any element ever being pushed.

Figure 1.6. A sequence diagram of the happy path of the observable and observer flow of interaction. In this scenario, an observer is subscribed to the observable by the application; the observable “pushes” three messages to the observers (only one in this case), and then notifies the observers that it has completed.

This observable algebra is formalized in the following expression (where * indicates zero or more times, ? indicates zero or one time, and | is an OR operator):

OnNext(t)* (OnCompleted() | OnError(e))?

When failing, the observers will be notified using the OnError method, and the exception object will be delivered to the observers to be inspected and handled (see figure 1.7). After an error (as well as after completion), no more messages will be pushed to the observers. The default strategy Rx uses when the observer doesn’t provide an error handler is to escalate the exception and cause a crash. You’ll learn about the ways to handle errors gracefully in chapter 10.

Figure 1.7. In the case of an error in the observable, the observers will be notified through the OnError method with the exception object of the failure.

In certain programming languages, events are sometimes offered as first-class citizens, meaning that you can define and register events with the language-provided keywords and types and even pass events as parameters to functions.

For languages that don’t support events as first-class citizens, the Observer pattern is a useful design pattern that allows you to add event-like support to your application. Furthermore, the .NET implementation of events is based on this pattern.

The Observer pattern was introduced by the Gang of Four (GoF) in Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software (Addison-Wesley Professional, 1994). The pattern defines two components: subject and observer (not to be confused with IObserver of Rx). The observer is the participant that’s interested in an event and subscribes itself to the subject that raises the events. This is how it looks in a Unified Modeling Language (UML) class diagram:

The observer pattern is useful but has several problems. The observer has only one method to accept the event. If you want to attach to more than one subject or more than one event, you need to implement more update methods. Another problem is that the pattern doesn’t specify the best way to handle errors, and it’s up to the developer to find a way to notify of errors, if at all. Last but not least is the problem of how to know when the subject is done, meaning that there will be no more notifications, which might be crucial for correct resource management. The Rx IObservable and IObserver are based on the Observer design pattern but extend it to solve these shortcomings.

1.2.4. Operators

Reactive Extensions also brings a rich set of operators. In Rx, an operator is a nice way to say operation, but with the addition that it’s also part of a domain-specific language (DSL) that describes event processing in a declarative way. The Rx operators allow you to take the observables and observers and create pipelines of querying, transformation, projections, and other event processors you may know from LINQ. The Rx library also includes time-based operations and Rx-specific operations for queries, synchronization, error handling, and so on.

For example, this is how you subscribe to an observable sequence of strings that will show only strings that begin with A and will transform them to uppercase:

Note

Don’t be scared if you don’t understand all the syntax or the meaning of each keyword. I explain all of them in the next chapters.

In this simple example, you can see the declarative style of the Rx operators—say what you want and not how you want it—and so the code reads like a story. Because I want to focus on the querying operators in this example, I don’t show how the observable is created. You can create observables in many ways: from events, enumerables, asynchronous types, and more. Those are discussed in chapters 4 and 5. For now, you can assume that the observables were created for you behind the scenes.

The operators and combinators (operators that combine multiple observables) can help you create even more complex scenarios that involve multiple observables. To achieve the resizable icon for the shops in the Shoppy example, you can write the following Rx expressions:

Even without knowing all the fine details of Reactive Extensions, you can see that the amount of code needed to implement this feature in the Shoppy application is small, and it’s easy to read. All the boilerplate of combining the various streams of data was done by Rx and saved you the burden of writing the isolated code fragments required to handle the events of data change.

1.2.5. The composable nature of Rx operators

Most Rx operators have the following format:

IObservable<T> OperatorName(arguments)

Note that the return type is an observable. This allows the composable nature of Rx operators; you can add operators to the observable pipeline, and each one produces an observable that encapsulates the behavior that’s been applied to the notification from the moment it was emitted from the original source.

Another important takeaway is that from the observer point of view, an observable with or without operators that are added to it is still an observable, as shown in figure 1.8.

Figure 1.8. The composable nature of Rx operators allows you to encapsulate what happens to the notification since it was emitted from the original source.

Because you can add operators to the pipeline not only when the observable is created, but also when the observer is subscribed, it gives you the power to control the observable even if you don’t have access to the code that created it.

1.2.6. Marble diagrams

A picture is worth a thousand words. That’s why, when explaining reactive programming and Rx in particular, it’s important to show the execution pipeline of the observable sequences. In this book, I use marble diagrams to help you understand the operations and their relationships.

Marble diagrams use a horizontal axis to represent the observable sequence. Each notification that’s carried on the observable is marked with a symbol, usually a circle (although other symbols are used from time to time), to distinguish between values. The value of the notification is written inside the symbol or as a note above it, as shown in figure 1.9.

Figure 1.9. Marble diagram with two observable sequences

In the marble diagram, time goes from left to right, and the distance between the symbols shows the amount of time that has passed between the two events. The longer the distance, the more time has passed, but only in a relative way. There’s no way to know whether the time is in seconds, hours, or another measurement unit. If this information is important, it’ll be written as a note.

To show that the observable has completed, you use the | symbol. To show that an error occurred (which also ends the observable), you use X. Figure 1.10 shows examples.

Figure 1.10. An observable can end because it has completed or because an error occurred.

To show the output of an operator (or multiple operators) on an observable, you can use an arrow that indicates the relationship between the source event and the result. Remember that each operator (at least the vast majority of operators) returns observables of its own, so in the diagram I’m writing the operator that’s part of the pipeline on the left side and the line that represents the observable returned from it on the right side. Figure 1.11 shows a marble diagram for the previous example of an observable sequence of strings that shows only the strings that begin with A and transforms them to uppercase.

Figure 1.11. Marble diagram that shows the output of various operators on the observable

Marble diagrams are used in this book to show the effects of operators as well as examples of combining operators to create observable pipelines. At this point, you might be wondering how observable sequences relate to nonobservable sequences. The answer is next.

1.2.7. Pull model vs. push model

Nonobservable sequences are what we normally call enumerables (or collections), which implement the IEnumerable interface and return an iterator that implements the IEnumerator interface. When using enumerables, you pull values out of the collection, usually with a loop. Rx observables behave differently: instead of pulling, the values are pushed to the observer. Tables 1.1 and 1.2 show how the pull and push models correspond to each other. This relationship between the two is called the duality principle.[5]

This observation was made by Erik Meijer; see http://mng.bz/0jO4.

Table 1.1. How IEnumerator and IObserver correspond to each other

|

IEnumerator |

IObserver |

|---|---|

| MoveNext—when false | OnCompleted |

| MoveNext—when exception | OnError(Exception exception) |

| Current | OnNext(T) |

Table 1.2. How IEnumerable and IObservable correspond to each other

|

IEnumerable |

IObservable |

|---|---|

| IEnumerator GetEnumerator(void) | IDisposable Subscribe(IObserver)[a] |

There’s one exception to the duality here, because the twin of the GetEnumerator parameter (which is void) should have been transformed to the Subscribe method return type (and stay void), but instead IDisposable was used.

Observables and observers fill the gap .NET had when dealing with an asynchronous operation that needs to return a sequence of values in a push model (pushing each item in the sequence). Unlike Task<T> that provides a single value asynchronously, or IEnumerable that gives multiple values but in a synchronous pull model, observables emit a sequence of values asynchronously. This is summarized in table 1.3.

Table 1.3. Push model and pull model data types

|

Single value |

Multiple values |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pull/Synchronous/Interactive | T | IEnumerable<T> |

| Push/Asynchronous/Reactive | Task<T> | IObservable<T> |

Because a reverse correspondence exists between observables and enumerables (the duality), you can move from one representation of a sequence of values to the other. A fixed collection, such as List<T>, can be transformed to an observable that emits all its values by pushing them to the observers. The more surprising fact is that observables can be transformed to pull-based collections. You’ll dive into the details of how and when to make those transformations in later chapters. For now, the important thing to understand is that because you can transform one model into the other, everything you can do with a pull-based model can also be done with the push-based model. So when you face a problem, you can solve it in the easiest model and then transform the result if needed.

The last point I’ll make here is that because you can look at a single value as if it were a collection of one item, you can by the same logic take the asynchronous single item—the Task<T>—and look at it as an observable of one item, and vice versa. Keep that in mind, because it’s an important point in understanding that “everything is an observable.”

1.3. Working with reactive systems and the Reactive Manifesto

So far, we’ve discussed how Rx adds reactiveness to an application. Many applications aren’t standalone, but rather part of a whole system that’s composed of more applications (desktop, mobile, web), servers, databases, queues, service buses, and other components that you need to connect in order to create a working organism. The reactive programming model (and Rx as an implementation of that model) simplifies the way an application handles the propagation of changes and the consumption of events, thus making the application reactive. But how can you make a whole system reactive?

As a system, reactiveness is defined by being responsive, resilient, elastic, and message-driven. These four traits of reactive systems are defined in the Reactive Manifesto (www.reactivemanifesto.org), a collaborative effort of the software community to define the best architectural style for building a reactive system. You can join the effort of raising awareness about reactive systems by signing the manifesto and spreading the word.

It’s important to understand that the Reactive Manifesto didn’t invent anything new; reactive applications existed long before it was published. An example is the telephone system that has existed for decades. This type of distributed system needs to react to a dynamic amount of load (the calls), recover from failures, and stay available and responsive to the caller and the callee 24/7, and all this by passing signals (messages) from one operator to the other.

The manifesto is here to put the reactive systems term on the map and to collect the best practices of creating such a system. Let’s drill into those concepts.

1.3.1. Responsiveness

When you go to your favorite browser and enter a URL, you expect that the page you were browsing to will load in a short time. When the loading time is longer than a few milliseconds, you get a bad feeling (and may even get angry). You might decide to leave that site and browse to another. If you’re the website owner, you’ve lost a customer because your website wasn’t responsive.

Responsiveness of a system is determined by the time it takes for the system to respond to the request it received. Obviously, a shorter time to respond means that the system is more responsive. A response from a system can be a positive result, such as the page you tried to load or the data you tried to get from a web service or the chart you wanted to see in the financial client application. A response can also be negative, such as an error message specifying that one of the values you gave as input was invalid.

In either case, if the time that it takes the system to respond is reasonable, you can say that the application is responsive. But a reasonable time is a problematic thing to define, because it depends on the context and on the system you’re measuring. For a client application that has a button, it’s assumed that the time it takes the application to respond to the button click will be a few milliseconds. For a web service that needs to make a heavy calculation, one or two seconds might also be reasonable. When you’re designing your application, you need to analyze the operations you have and define the bounds of the time it should take for an operation to complete and respond. Being responsive is a goal that reactive systems are trying to achieve.

1.3.2. Resiliency

Every once in a while, your system might face failures. Networks disconnect, hard drives fail, electricity shuts down, or an inner component experiences an exceptional situation. A resilient system is one that stays responsive in the case of a failure. In other words, when you write your application, you want to handle failures in a way that doesn’t prevent the user from getting a response.

The way you add resiliency to an application is different from one application to another. One application might catch an exception and return the application to a consistent state. Another application might add more servers so that if one server crashes, another one will compensate and handle the request. A good principle you should follow to increase the resiliency of your system is to avoid a single point of failure. This can be done by making each part of your application isolated from the other parts; you might separate parts into different AppDomains, different processes, different containers, or different machines. By isolating the parts, you reduce the risk that the system will be unavailable as a whole.

1.3.3. Elasticity

The application that you’re writing will be used by a number of users—hopefully, a large number of users. Each user will make requests to your system that may result in a high load that your system will need to deal with. Each component in your system has a limit on the load level it can deal with, and when the load goes above that limit, requests will start failing and the component itself may crash. This situation of increasing load can also be caused by a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack that your system is experiencing.

To overcome the causes of overload, your system needs to be elastic: it needs to span instances as the load increases and remove instances as the load decreases. This kind of automatic behavior has been much more apparent since the cloud entered our lives. When running on the cloud, you get the illusion of infinite resources; with a few simple configurations, you can set your application to scale up or down, depending on the threshold you define. You need to remember only that a cost is associated with running extra servers.

1.3.4. Message driven

At this point, you can say that responsiveness is your goal, resiliency is the way to ensure that you keep being responsive, and elasticity is one method for being resilient. The missing piece of the puzzle of reactive systems is the way that the parts of a system communicate with each other to allow for the type of reactiveness we’ve explored.

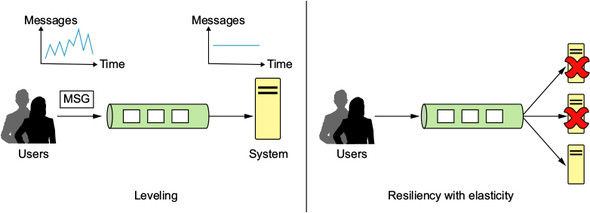

Asynchronous message passing is the communication process that best suits our needs, because it allows us to control the load level on each component without limiting producers—normally with an intermediate channel such as a queue or service bus. It allows routing of messages to the right destination and resending of failing messages in case a component crashes. It also adds transparency to the inner system components, because users don’t need to know the internal system structure except the type of messages it can handle. Being message driven is what makes all the other reactive concepts possible. Figure 1.12 shows how the message-driven approach using a message queue helps level the rate of message processing in the system and enables resiliency and elasticity.

Figure 1.12. The relationship of a message-driven approach to load leveling and elasticity. On the left, messages are arriving at a high frequency, but system processing is leveled to a constant rate, and the queue is filling faster than it’s emptied. On the right, even if the processing worker role has crashed, users can still fill the queue; and when the system recovers and adds a new worker, the processing continues.

In the figure, the participants are communicating in a message-driven approach through the message queue. The client sends a message that’s later retrieved by the server. This asynchronous communication model provides greater control over the processing in the system—controlling the rate and dealing with failures. Many implementations for message queuing exist, with different feature sets. Some allow the persistence of the messages, which provides durability, and some also give a “transactional” delivery mode that locks the message until the consumer signals that the processing completed successfully. No matter which message queue (or message-driven platform) you choose, you’ll need to somehow get ahold of the messages that were sent and start processing them. This is where Rx fits in.

1.3.5. Where is Rx?

The Reactive Extensions library comes into play inside the applications that compose a reactive system, and it relates to the message-driven concept. Rx isn’t the mechanism to move messages between applications or servers, but rather it’s the mechanism that’s responsible for handling the messages when they arrive and passing them along the chain of execution inside the application. It’s important to state that working with Rx is something you can do even if you’re not developing a full system with many components. Even a single application can find Rx useful for reacting to events and the types of messages that the application may want to process. The relationships between all the Reactive Manifesto concepts and Rx are captured in figure 1.13.

Figure 1.13. The relationships between the Reactive Manifesto core concepts. Rx is positioned inside the messagedriven concept, because Rx provides abstractions to handle messages as they enter the application.

To get a fully reactive system, all the concepts in the diagram must exist. Each one can be implemented differently in different systems. Rx is one way to allow easier consumption of messages, so it’s shown as part of the message-driven block. Rx was introduced as a way to handle asynchronous and event-based programs, as in the case of messages, so it’s important that I explain what it means to be asynchronous and why it’s important.

1.4. Understanding asynchronicity

Asynchronous message passing is a key trait of a reactive system. But what exactly is asynchronicity, and why is it so important to a reactive application? Our lives are made up of many asynchronous tasks. You may not be aware of it, but your everyday activities would be annoying if they weren’t asynchronous by nature. To understand what asynchronicity is, you first need to understand nonasynchronous execution, or synchronous execution.

Definition

Synchronous: Happening, existing, or arising at precisely the same time

Synchronous execution means that you have to wait for a task to complete before you can continue to the next task. A real-life example of synchronous execution takes place at a fast-food restaurant: you approach the staff at the counter, decide what to order while the clerk waits, order your food, and wait until the meal is ready. The clerk waits until you hand over the payment and then gives you the food. Only then you can continue the next task of going to your table to eat. This sequence is shown in figure 1.14.

Figure 1.14. Synchronous food order in which every step must be completed before going to the next one

This type of sequence feels like a waste of time (or, better said, a waste of resources), so imagine how your applications feel when you do the same for them. The next section demonstrates this.

1.4.1. It’s all about resource use

Imagine what your life would be like if you had to wait for every single operation to complete before you could do something else. Think of the resources that would be waiting and used at that time. The same issues are also relevant in computer science:

writeResult = LongDiskWrite(); response = LongWebRequest(); entities = LongDatabaseQuery();

In this synchronous code fragment, LongDatabaseQuery won’t start execution until LongWebRequest and LongDiskWrite complete. During the time that each method is executed, the calling thread is blocked and the resources it holds are practically wasted and can’t be used to serve other requests or handle other events. If this were happening on the UI thread, the application would look frozen until the execution finishes. If this were happening on a server application, at some point you might run out of free threads and requests would start being rejected. In both cases, the application stops being responsive.

The total time it takes to run the preceding code fragment is as follows:

- total_time = LongDiskWritetime + LongWebRequesttime + LongDatabaseQuerytime

The total completion time is the sum of the completion time of its components. If you could start an operation without waiting for a previous operation to complete, you could use your resources much better. This is what asynchronous execution is for.

Asynchronous execution means that an operation is started, but its execution is happening in the background and the caller isn’t blocked. Instead, the caller is notified when the operation is completed. In that time, the caller can continue to do useful work.

In the food-ordering example, an asynchronous approach would be similar to sitting at the table and being served by a waiter. First, you sit at the table, and the waiter comes to hand you the menu and leaves. While you’re deciding what to order, the waiter is still available to other customers. When you’ve decided what meal you want, the waiter comes back and takes your order. While the food is being prepared, you’re free to chat, use your phone, or enjoy the view. You’re not blocked (and neither is the waiter). When the food is ready, the waiter brings it to your table and goes back to serve other customers until you request the bill and pay.

This model is asynchronous: tasks are executed concurrently, and the time of execution is different from the time of the request. This way, the resources (such as the waiter) are free to handle more requests.

In a computer program, we can differentiate between two types of asynchronous operations: CPU-based and I/O-based.

In a CPU-based operation, the asynchronous code runs on another thread, and the result is returned when the execution on the other thread finishes.

In an I/O-based operation, the operation is made on an I/O device such as a hard drive or network. On a network, a request is made to another machine (by using TCP or UDP or another network protocol), and when the OS on your machine gets a signal from the network hardware by an interrupt that the result came back, then the operation will be completed.

In both cases, the calling thread is free to execute other tasks and handle other requests and events.

There’s more than one way to run code asynchronously, and it depends on the language that’s used. Appendix A shows the ways this can be done in C# and dives deeper into bits and bytes of each one. For now, let’s look at one example of doing asynchronous work by using the .NET implementation of futures—the Task class:

The asynchronous version of the preceding code fragment looks like the following:

taskA = LongDiskWriteAsync();

taskB = LongWebRequestAsync();

taskC = LongDatabaseQueryAsync();

Task.WaitAll(taskA, taskB, taskC);

In this version, each method returns Task<T>. This class represents an operation that’s being executed in the background. When each method is called, the calling thread isn’t blocked, and the method returns immediately. Then the next method is called while the previous method is still executing. When all the methods are called, you wait for their completion by using the Task.WaitAll method that gets a collection of tasks and blocks until all of them are completed. Another way to write this is as follows:

taskA = LongDiskWriteAsync(); taskB = LongWebRequestAsync(); taskC = LongDatabaseQueryAsync(); taskA.Wait(); taskB.Wait(); taskC.Wait();

This way, you get the same result; you wait for each task to complete (while they’re still running in the background). If a task is already completed when you call the Wait method, it will return immediately.

The total time it takes to run the asynchronous version of the code fragment is as follows:

- total_time = MAX(LongDiskWritetime, LongWebRequesttime, LongDatabaseQuerytime)

Because all of the methods are running concurrently (and maybe even in parallel), the time it takes to run the code will be the time of the longest operation.

1.4.2. Asynchronicity and Rx

Asynchronous execution isn’t limited to being handled only by using Task<T>. In appendix A, you’ll be introduced to other patterns used inside the .NET Framework to provide asynchronous execution.

Looking back at IObservable-<T>, the Rx representation of a time-variant variable, you can use it to represent any asynchronous pattern, so when the asynchronous execution completes (successfully or with an error), the chain of execution will run and the dependencies will be evaluated. Rx provides methods for transforming the various types of asynchronous execution (such as Task<T>) to IObservable<T>.

For example, in the Shoppy app, you want to get new discounts not only when your location changes, but also when your connectivity state changes to online—for example, if your phone loses its signal for a short time and then reconnects. The call to the Shoppy web service is done in an asynchronous way, and when it completes, you want to update your view to show the new items:

In this example, you’re reacting to the connectivity changes that are carried on the myConnectivity observable. Each time a change in connectivity occurs, you check to see whether it’s because you’re online, and if so, you call the asynchronous GetDiscounts method. When the method execution is complete, you select the result that was returned. This result is what will be pushed to the observers of the new-Discounts observable that was created from your code.

1.5. Understanding events and streams

In a software system, an event is a type of message that’s used to indicate that something has happened. The event might represent a technical occurrence—for example, in a GUI application you might see events on each key that was pressed or each mouse movement. The event can also represent a business occurrence, such as a money transaction that was completed in a financial system.

An event is raised by an event source and consumed by an event handler. As you’ve seen, events are one way to represent time-variant values. And in Rx, the event source can be represented by the observable, and an event handler can be represented by the observer. But what about the simple data that our application is using, such as data sitting in a database or fetched from a web server. Does it have a place in the reactive world?

1.5.1. Everything is a stream

The application you write will ultimately deal with some kind of data, as shown in figure 1.15. Data can be of two types: data at rest and data in motion. Data at rest is stored in a digital format, and you usually read it from persisted storage such as a database or files. Data in motion is moving on the network (or other medium) and is being pushed to your application or pulled by your application from any external source.

Figure 1.15. Data in motion and data at rest as one data stream. The connection points from the outside environment are a perfect fit for creating observables. Those observables can be merged easily with Rx to create a merged observable that the inner module can subscribe to without knowing the exact source of a data element.

No matter what type of data you use in your application, it’s time to understand that everything can be observed as a stream, even data at rest and data that looks static to your application. For example, configuration data is perceived as static, but even configuration changes at some point, either after a long time or short time. From your application’s perspective, it doesn’t matter; you want to be reactive and handle those changes as they happen. When you look at the data at rest as another data stream, you can more easily combine both types of data. For your application, it doesn’t matter where the data came from.

For example, application startup usually loads data from its persisted storage to restore its state (the one that was saved before the application was closed). This state can, of course, change during the application run. The inner parts of your application that care about the state can look at the data stream that carries it. When the application starts, the stream will deliver the data that was loaded, and when the state changes, the stream will carry the updates.

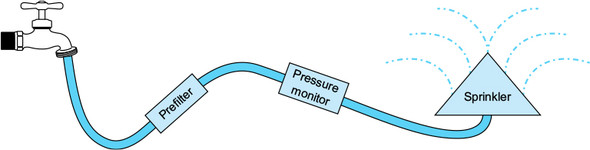

A nice analogy I like to use for explaining streams is a water hose, but this hose has data packets going through it, just like the one you see in figure 1.16. When using a water hose, you can do many things with it. You can put filters at the end. You can add different hose heads that give different functionality. You can add pressure monitors to help you regulate the flow. You can do the same things with your data stream. You’ll want to build a pipeline that lets the information flow through it, to eventually give an end result that suits your logic; this includes filtering, transformations, grouping, merging, and so on.

Figure 1.16. A data stream is like a hose: every drop of water is a data packet that needs to go through stations until it reaches the end. Your data also needs to be filtered and transformed until it gets to the real handler that does something useful with it.

The data and event streams are a perfect fit for Rx observables. Abstracting them with an IObservable enables you to make a composition of the operators and create a complex pipeline of execution. This is similar to what you did with the Shoppy example, where a call to a server obtained the discounts as part of a more complex pipeline of execution that also used filtering (on the connectivity) and eventually refreshed the view (like a sprinkler splashing water).

1.6. Summary

This chapter covered what being reactive means and how you can use Rx to implement reactive programming in your applications.

- In reactive programming, you use time-variant variables that hold values that change by reacting to changes happening to their dependencies. You saw examples of these variables in the Shoppy example: location, connectivity, iconSize, and so on.

- Rx is a library developed by Microsoft to implement reactive programming in .NET applications.

- In Rx, time-variant variables are abstracted by observable sequences that implement the IObservable<T> interface.

- The observable is a producer of notifications, and observers subscribe to it to receive those notifications.

- Each observer subscription is represented as IDisposable that allows unsubscribing at any time.

- Observers implement the IObserver<T> interface.

- Observables can emit a notification with a payload, notify on its completion, and notify on an error.

- After an observable notifies an observer on its completions or about an error, no more notifications will be emitted.

- Observables don’t always complete; they can be providers of potentially unbounded notifications.

- Observables can be “quiet,” meaning they have never pushed any element and never will.

- Rx provides operators that are used to create pipelines of querying, transformation, projections, and more in the same syntax that LINQ uses.

- Marble diagrams are used to visualize the Rx pipelines.

- Reactive systems are defined as being responsive, resilient, elastic, and message driven. These traits of reactive systems are defined in the Reactive Manifesto.

- In a reactive system, Rx is placed in the message-driven slot, as the way you want to handle the messages the application is receiving.

- Asynchronicity is one of the most important parts of being reactive, because it allows you to better use your resources and thus makes the application more responsive.

- “Everything is a stream” explains why Rx makes it easy to work with any source, even if it’s a data source such as a database.

In the next chapter, you’ll get the chance to build your first Rx application, and you’ll compare it with writing the same application in the traditional event-handling way. You’ll see for yourself how awesome Rx is.