Chapter 3. Functional thinking in C#

- Blending C# with functional techniques

- Using delegates and lambda expressions

- Querying collections by using LINQ

The object-oriented paradigm offers great productivity in application development. It makes projects more manageable by decomposing complex systems into classes, and objects are silos that you can concentrate on separately. Yet other paradigms have gathered attention in recent years, especially the functional programming paradigm. Functional programming languages, together with a functional way of thinking, greatly influenced the way Rx was designed and used. Specifically, the functional programming concepts of anonymous types, first-order functions, and function composition are an integral part of Rx that you’ll see used heavily throughout the book and in your everyday work with Rx.

Some of the attention functional programming is receiving arises from functional languages being good for multithreaded applications. Rx excels in creating asynchronous and concurrent processing pipelines, which were also inspired by functional thinking. Although C# is considered an object-oriented language, it has evolved over the years and added aspects that exist in functional programming.

.NET even has a functional programming language of its own, named F#, which runs on top of the Common Language Runtime (CLR) in the same way C# does. Using functional programming techniques can make your code cleaner and easier to read and can change the way you think when writing code, eventually making you more productive. Rx is highly influenced by the functional way of thinking, so it’s good to understand those concepts in order to more easily adopt the Rx way of thinking.

The concepts in this chapter may not be new to you. You can skip to the next chapter if you wish, but I encourage you to at least briefly review the concepts to refresh your memory.

3.1. The advantages of thinking functionally

As computer science evolves, new languages appear with new concepts and techniques. All these languages share the same underlying purpose: improving developer productivity and program robustness. Productivity and robustness have many faces: shorter code, readable statements, internal resource management, and so on. Functional programming languages also try to achieve those goals. Although many types of functional programming languages exist, each with unique characteristics, we can see their similarities:

- Declarative style of programming— This is based on the concept of “Tell what, not how.”

- Immutability— Values can’t be modified; instead, new values are created.

- First-class functions— Functions are the primary building block used.

With object-oriented languages, developers think about programs as a collection of objects that interact with each other. This allows you to create modular code by encapsulating data and behavior that relates to the data in an object. This modularity, again, improves the productivity of the developer and makes your program more robust because it’s easier for the developer to understand the code (less detail to remember) and concentrate effort on a specific module when writing new code or changing (or fixing) existing ones.

3.1.1. Declarative programming style

In the first two chapters, you saw examples of the declarative programming style. In this style, you write your program statements as a description of what you want to achieve as the result instead of specifying how you want this to be done. It’s up to the environment to figure out how to do it best. Consider this example of an English statement in an imperative style (the how) and declarative style (the what):

- Imperative— For each customer in the list of customers, take the location and print the city name.

- Declarative— Print the city name of every customer in the list.

A declarative style makes it easier to grasp the code you write, which leads to better productivity and usually makes your code less error prone. The next code block shows another example of the declarative programming style, this time using HTML that produces what you see in figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. A simple web page that has a title, a heading, and a paragraph

To create this page, you don’t have to write the rendering logic or the layout management and set the position for each element. Instead, all you have to do is to write this short HTML script:

<html>

<head>

<title>this is the page title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is a Heading</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

</body>

</html>

Even if you don’t know HTML, it’s easy to see that this example only declares the outcome you want to see and doesn’t deal with the technical details of making the browser do it. With a declarative language such as HTML, you can create a complex page with little effort. You want to attain the same results with the C# code you write, and you’ll see examples of that in the rest of this chapter. One thing you need to pay attention to is that because you’re indicating the what and not the how, how can you know what will happen to the system? Could there be side effects? It turns out that functional programming solves this problem from the start, as you’ll see next.

3.1.2. Immutability and side effects

Consider this method, which prints a message to the console:

public static void WriteRedMessage(string message) { Console.ForegroundColor = ConsoleColor.Red; Console.WriteLine(message); }

This short method causes a side effect to the program: the method changes a shared state in the system, the console color in this case. Side effects can come in different flavors and are sometimes hidden inside the code. If you change the method signature and remove the word Red from the method name, as shown in the following code sample, the side effect still happens:

public static void WriteMessage(string message)

But now it’s far more difficult to predict that this method will cause the side effect of changing the color of the console output. Side effects aren’t limited to console color, of course; they also include changes to a shared object state, such as a list of items that’s modified (as you saw in the previous chapter). Side effects can cause all kinds of bugs in your code—for example, in concurrent execution the code is reached from two places (like threads) at the same time and leads to race conditions. Side effects can also cause your code to be harder to track and predict, thus making it harder to maintain.

Functional programming languages solve the side-effect problem by preventing it in the first place. In functional programming, every object is immutable. You can’t modify the object state. After the value is set, it never changes; instead, new objects are created. This concept of immutability shouldn’t be new to you. Immutability exists in C# as well, such as in the type string. For example, try to answer what this next program will print:

string bookTitle = "Rx.NET in Action"; bookTitle.ToUpper(); Console.WriteLine("Book Title: {0}", bookTitle);

If your answer is Rx.NET in Action, you’re correct. In C#, strings are immutable. All the methods that transform a string’s content don’t really change it; instead, they create a new string instance with the modifications. The previous example should’ve been written like this:

string bookTitle = "Rx.NET in Action"; string uppercaseTitle = bookTitle.ToUpper(); Console.WriteLine("Book Title: {0}", uppercaseTitle);

This version of the code stores the result of the ToUpper call in a new variable. This variable holds a different string instance with the uppercase value of the book title.

The immutability implies that calling a function ends only with the function computing its result, without any other effect that the programmer needs to worry about. This takes away a major source of bugs and makes the functions idempotent—calling a function with the same input always ends with the same result, no matter whether it was applied once or multiple times.

A word about concurrency

The idempotency that you get from the immutability makes the program deterministic and predictable and makes the order in which execution happens irrelevant, making it a perfect fit for concurrent execution.

Writing concurrent code is hard, as you saw in the previous chapter. When you take sequential code and try to run it in parallel, you could find yourself facing bugs. With side effect-free and immutable code, this problem doesn’t exist. Running the code from different threads won’t cause any synchronization issues, because you have nothing to synchronize. Knowing that using functional programming languages makes writing concurrent applications easier, it’s no wonder that functional programming languages started to gain more interest in recent years and became the de facto community choice for building large-scale concurrent applications. Just to name a few, companies such as Twitter, LinkedIn, and AT&T are known to use functional programming in their systems.

3.1.3. First-class functions

The name functional programming is used because a function is the basic construct that you work with. It’s one of the language primitives, like an int or a string, and similar to other primitive types, the function is a first-class citizen, which means it can be passed as an argument and be returned from a function. Here’s an example in F# (a functional programming language that’s part of .NET):

let square x = x * x let applyAndAdd f x y = f(x) + f(y)

Here we define a function, square, that calculates the square of its argument. We then define a new function, applyAndAdd, that takes three arguments: the first argument is a function that’s applied to the two other arguments, and then the results are summed.

Note

If you find this confusing, don’t worry. Read the rest of the chapter and then come back and read this short section again.

When you call the applyAndAdd function and pass the square function as the first argument together with two numbers as the other arguments, you get the sum of two squares. For example, apply-AndAdd square 5 3 outputs the number 34, as shown in figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2. In functional programming languages, functions can be passed as arguments. This is the expression tree of the call to applyAndAdd f x y with f: square, x: 5, y: 3.

Functions that receive functions as their arguments or return functions as their return values are called higher-order functions. With higher-order functions, you can compose new functions and add new behaviors to existing functions by changing the inner function they use, as you did in the applyAndAdd example. This way, you can extend the “language” that your code uses and adapt it to your domain.

3.1.4. Being concise

The core functional programming concepts mentioned earlier in the chapter serve the same purpose that makes functional thinking a powerful tool you should embrace: making your code concise and short.

Writing declaratively means that you can hide the complexity required to achieve a result and instead focus on the result that you want to achieve. This is done using the compositional nature of first-class and higher-order functions that create the glue between the various parts of your code. The expressiveness of your program is better achieved when you know that no side effects will arise and cause uncertainty in the outcome of the execution. Working with an immutable data structure enables you to be certain that the function will always end the same predictable way.

Writing code that’s concise makes you more productive when creating new code or when changing existing code, even if it’s new to you. Figure 3.3 displays the key elements for productivity.

Figure 3.3. The key benefit of functional programming is that it makes you more productive. The key elements for productivity are illustrated here.

The key elements shown in figure 3.3 are where the true benefits of functional programming lie. It’s important for you to know that so you can achieve the same advantages when writing programs in C#.

3.2. First-class and higher-order functions using delegates and lambdas

When C# was introduced in 2002, it was possible to make “function pointers” that you could pass as arguments and hold as class members. These function pointers are known as delegates. Over the years, C# became a multi-paradigm language that supports not only object-oriented programming but also event-driven programming or simple procedural programming. Functional programming also started to influence language as the years went by, and delegates became the underlying mechanism to support functions as first-class citizens in the language.

3.2.1. Delegates

In C#, a delegate is a type that represents references to methods. Delegates are most commonly used with .NET events, but in this chapter, you’ll see how to use them to spice up code with functional programming techniques.

The delegate type is defined with the exact signature of the methods you want the delegate to reference. For example, if you want to create a reference to methods that receive two string parameters and return a bool, figure 3.4 shows how to define the delegate type.

Figure 3.4. Declaration of a delegate type for methods that receive two strings and return an integer

After creating the delegate type, you can reference methods with the same signature by creating a new instance of the delegate and passing the method you want to reference:

ComparisonTest delegateInstance = new ComparisonTest( <the method> );

Say you have a class that holds different methods that compare strings:

class StringComparators { public static bool CompareLength(string first, string second) { return first.Length == second.Length; } public bool CompareContent(string first, string second) { return first == second; } }

You can then use your delegate type to reference the comparison methods:

The sample output from the previous code is as follows:

CompareContent returned: False CompareLength returned: True

Beginning with C# 2.0 it’s much easier to create delegates. You can simply assign the method to the delegate variable (or parameter):

ComparisonTest test2 = comparators.CompareContent;

With delegates, you can make something similar to the higher-order functions that functional programming languages have. The next method checks whether two string arrays are similar by traversing the items in both collections and checking them against each other using a comparison function that was passed to a delegate reference.

Listing 3.1. AreSimilar method uses a delegate as a parameter type

The method receives the two arrays and calls the tester on every two corresponding items to check whether they’re similar. The tester is referencing a method that was sent as an argument. Here you’re calling the AreSimilar method and passing the CompareLength method as an argument:

string[] cities = new[] { "London", "Madrid", "TelAviv" }; string[] friends = new[] { "Minnie", "Goofey", "MickeyM" }; Console.WriteLine("Are friends and cities similar? {0}", AreSimilar(friends,cities, StringComparators.CompareLength));

The output result for this sample is as follows:

Are friend and cities similar? True

3.2.2. Anonymous methods

The problem with delegates as you’ve seen them so far is that they force you to write a method in a class—this is called a named method. This burden slows you down and therefore hurts your productivity. Anonymous methods are a feature in C# that enable you to pass a code block as a delegate value:

ComparisonTest lengthComparer = delegate (string first, string second) { return first.Length == second.Length; }; Console.WriteLine("anonymous method returned: {0}", lengthComparer("Hello", "World"));

The anonymous method can also send the code block as an argument:

AreSimilar(friends, cities,

delegate (string s1, string s2) { return s1 == s2; });

Anonymous methods make it far easier to create higher-order functions in your C# program and reuse existing code, as with the AreSimilar method in the previous example. You can use the method over and over and pass different comparison methods, improving the extendibility of your program.

Closures (captured variables)

Anonymous methods are created within a scope, such as a method scope or a class scope. The code block of your anonymous method can access anything that’s visible to it in that scope—variables, methods, and types, to name a few. An an example:

int moduloBase = 2; var similarByMod=AreSimilar(friends, cities, delegate (string s1, string s2) { return ((str1.Length % moduloBase) == (str2.Length % moduloBase)); });

Here the anonymous method uses a variable that’s declared in the outer scope. The variable moduloBase is called a captured variable, and its lifetime now spans the lifetime of the anonymous method that uses it.

The anonymous method that uses captured variables is called a closure. Closures can use the captured variable even after the scope that created it has completed:

When running this example, you get this interesting output

the modulo base is: 3 Similar by modulo: False

The anonymous method was created in a scope that’s different from the scope that uses it, but the anonymous method still has access to a variable declared in that scope. Not only that, but the value that the anonymous method sees is the last one that the variable was holding. This leads to a powerful observation:

The value of a captured variable that a closure uses is evaluated at the time of the method execution and not at the time of declaration.

Captured variables can cause confusion from time to time, so consider this example and try to determine what will print:

The output of this example might not be what you expected. Instead of printing the numbers 0 to 4, this code prints the number 5 five times. This is because when each action is executed, it reads the value of i, and the value of i is the value it received in the last iteration of the loop, which is 4.

3.2.3. Lambda expressions

To make it even simpler to create anonymous methods, you can use the lambda expression syntax introduced in C# 3.0. Lambda expressions enable you to create anonymous methods that are more concise and more closely resemble the functional style.

Here’s an example of an anonymous method written as both anonymous method syntax and with lambda expressions:

The lambda expression is written as a parameter list, followed by =>, which is followed by an expression or a block of statements.

If the lambda expression receives only one parameter, you can omit the parentheses:

x => Console.WriteLine(x);

The lambda expression also uses type inference of the parameters. You can, however, write the types of the parameters explicitly:

ComparisonTest x = (string s1, string s2) => s1==s2;

Typically, you want your lambda expression to be short and concise, but it’s not always possible to have only one statement in your lambda expression. If your lambda contains more than one expression, you need to use curly braces and write the return statement explicitly in case it needs to return a value:

Lambda expressions are used heavily with Rx because they make your processing pipeline short and expressive, which is cool! But you still have the requirement to create new delegate types each time you want to specify a method signature for the method types to which you want to receive a reference, which is far from ideal. That’s why you usually won’t create new delegate types but instead use Action and Func.

3.2.4. Func and Action

A delegate type is a way to enforce the method signatures you want to receive as a parameter or set as a variable. Most of the time, you’re not interested in creating a new type of delegate to enforce that constraint; you only want to state what you’re expecting. For example, the following two delegate types are the same except for the names used:

public delegate bool NameValidator(string name); public delegate bool EmailValidator(string email);

Because the two delegate types definitions are the same, you can set both to the same lambda expression:

NameValidator nameValidator = (name) => name.Length > 3; EmailValidator emailValidator = (email) => email.Length > 3;

You name the two delegate types after the functionality that the assigned code needs to have—checking the validity of a name and of an email address. You could’ve changed the name to reflect the signature:

public delegate bool OneParameterReturnsBoolean(string parameter);

Now you have a delegate type that’s reusable, but only to code that has access to your definition, which cries for a standard implementation. The .NET Framework contains reusable delegate type definitions named Func<...> and Action<...>:

- Func is a delegate type that returns a value and can receive parameters.

- Action is a delegate type that can receive parameters but returns no value.

The .NET Framework contains 17 definitions of Func and Action, each for different numbers of parameters that the referenced method receives. The Func and Action types are located under the System namespace in the mscorlib assembly.

To reference a method that has no parameters and doesn’t return a value, you use the following definition of Action:

public delegate void Action();

and for a method that has two parameters and doesn’t return a value, you use this definition of Action:

public delegate void Action<in T1, in T2>(T1 arg1, T2 arg2);

To use the Action delegate, you need to specify the types of parameters. Here’s an example of a method that traverses a collection and makes an operation on each item by using an Action of an integer:

public static void ForEachInt(IEnumerable<int> collection, Action<int> action) { foreach (var item in collection) { action(item); } }

Now you can call the ForEachInt method from your code like this:

var oddNumbers = new[] { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 }; ForEachInt(oddNumbers, n => Console.WriteLine(n));

This code prints all the numbers in the oddNumbers collection. You can use the ForEachInt method with a different collection and different option. Because the Action delegate is generic, you can use that and create your generic version of ForEach:

public static void ForEach<T>(IEnumerable<T> collection, Action<T> action) { foreach (var item in collection) { action(item); } }

Now you can use ForEach with any collection:

Because Console.WriteLine is a method that can accept any number of parameters, you can write the previous example this way too:

ForEach(new[] { 1, 2, 3 }, Console.WriteLine); ForEach(new[] { "a", "b", "c" }, Console.WriteLine); ForEach(new[] { ConsoleColor.Red, ConsoleColor.Green, ConsoleColor.Blue}, Console.WriteLine));

Whenever you need to create a delegate for methods that return a value, you should use the type Func. This type (like Action) receives a variable number of generic parameters corresponding to the types of parameters that the method referenced by the delegate can receive. Unlike Action, in the Func definition the last generic parameter is the type of return value:

public delegate TResult Func<in T1,...,T16, out TResult>(T1 arg,...,T16 arg16);

and there’s a definition for a Func that gets no parameters:

public delegate TResult Func<out TResult>();

Using Func, you can extend your implementation of the ForEach method so that it’ll accept a filter (also known as a predicate). The filter is a method that accepts an item and returns a Boolean indicating whether it’s valid:

The filtering you added to the ForEach method can be exploited to act only on certain items in a collection—for instance, printing only even numbers:

![]()

With Action and Func, you can build classes and methods that can be extended without modifying their code. This is a nice implementation of the Open Close Principle (OCP) that says a type should be open for extension but closed to modifications. Following design principles such as the OCP can improve your code and make it more maintainable.

3.2.5. Using it all together

It’s nice to see that known design patterns such as Strategy, Command, and Factory (to name a few) can be expressed differently with Func and Action and demand less code from the developer.

Take, for example, the Strategy pattern, whose purpose is to allow extension of an algorithm by encapsulating an operation inside an object. Figure 3.5 shows the Strategy design pattern class diagram. In this design pattern, you have a Context class that performs an operation. This operation depends on an external part that contains a specific algorithm. The algorithm is implemented by a class that implements the IStrategy interface.

Figure 3.5. The Strategy pattern class diagram. The context’s operation can be extended by providing different implementations of the strategy.

The Strategy design pattern is useful when you want to allow extension points in a workflow and give the user of your code the power to control it. The pattern is used in many applications and even in the .NET Framework itself, such as in the case of the IComparer<T> interface.

The IComparer<T> interface is part of the System.Collections.Generic namespace and is used to compare two objects of the same type. A typical use of the IComparer<T> interface is in the Sort method of List<T>, so if you want to sort a list of strings by their length (and by lexicographical order), this is how you do it. First, you create a new IComparer derived class:

You run the sort like this:

var words = new List<string> { "ab", "a", "aabb", "abc" }; words.Sort(new LengthComparer()); Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", words));

The output of this sort is the collection { "a", "ab"," abc", "aabb" };.

This works pretty well, but it’s annoying, because each time you want a new comparison method, you need to create a new class. Instead, you can use the power of Func and create a generic IComparer that you can tune to your needs:

This is somehow an adapter between the IComparer and Func. To use it, you pass the required comparison code as a lambda expression (or delegate):

With the generic version of IComparer, you can create new comparison code quickly and keep it close to where it’s used so it’s ready to read and is much more concise.

Using Func as a factory

Another pattern that the Func style can make shorter and more fun is the lazy-loading pattern in which Func is used as a factory (an object creator). Lazy loading means that instead of creating something in advance, you’ll create it just in time, when it’s used.

HeavyClass can take a long time to create or holds many resources so that you want to delay the time they take from the system. Next is an example of a heavy class that’s used in another class. You want the object of the heavy class created only when something in the code is trying to use it:

This code has a couple of issues. First, it’s repeatable; if you have 10 lazy-loaded types, you need to create the same if-create-return sequence 10 times, and duplication of code can be error prone and boring. Second, you forgot about concurrency and synchronization again (and many do forget, so don’t feel bad). It’d be much better if someone else took care of those things for you, and luckily a tool exists for this.

Inside the System namespace you find the Lazy<T> class, whose purpose is to verify whether an instance was already created and, if not, to create it (once and only once). In our example, you could use Lazy<T> as shown here:

class ClassWithLazy { Lazy<HeavyClass> _lazyHeavyClass = new Lazy<HeavyClass>(); public void SomeMethod() { var myHeavy = _lazyHeavyClass.Value; //Rest of code that uses myHeavy } }

But what if the HeavyClass constructor needs an argument or if the process of creating it is more complex? For that, you can pass a Func that performs the creation of the object and returns it:

Delegates are a powerful feature of C#. For many years, their main use was when dealing with events, but since Action and Func were introduced, you can see how to use them to replace classic patterns by providing shorter, more readable, and concise code.

Still, something was missing. When you added new methods such as ForEach, it felt a bit like procedural code. You created a method that was exposed as a static from a class and when used, it didn’t feel like the natural object-oriented style. You’d prefer to use a regular method on the object you wanted to run it on. This is exactly the point of extension methods.

3.3. Method chaining with extension methods

One of the things that allows functional programming to be concise and declarative is the use of function composition and chaining, where functions are called one after the other such that the output of the first function becomes the input of the next one. Because the functions are first-class citizens, the output of a function can be a function by itself. The queries you write with Rx are written in the same compositional way and make the query look as if it’s a sentence in English, which makes it appealing to use. To understand how to add this kind of chaining behavior in your C# code, you first need to understand extension methods.

3.3.1. Extending type behavior with extension methods

In object-oriented programming, you create classes that contain both states (fields, properties, and so forth) and methods. After you create your class and compile it, you can’t extend it and add more methods or members unless you change its code and recompile it. At times, however, you’ll want to add methods that work on a class you already have—whether it’s a class you created or a class that you have access to, such as the types from the .NET Framework. To add those methods, you can create a new class and add methods that accept the class you want to extend as a parameter that resembles the programming style of procedural languages.

Extension methods, a feature added to .NET, enable you to “add” methods to a type. Adding a method to a type doesn’t mean you’re changing the type; instead, extension methods allow you to use the same syntax of calling a method on an object but let the compiler convert it to a call on an external method. Let’s revise our implementation of ForEach:

static class Tools { public static void ForEach<T>(IEnumerable<T> collection, Action<T> action) { //ForEach implementation } }

To use the ForEach method, you need to pass the collection on which you want to iterate as a parameter. With extension methods, the call for ForEach looks like the following example. Note that this won’t compile just yet, because you haven’t defined an extension method:

var numbers = Enumerable.Range(1,10); numbers.ForEach(x=>Console.WriteLine(x));

At compile time, the compiler changes the given call to the regular static method call. To create extension methods, this is what you need to do:

- Create a static class.

- Create a public or internal static method.

- Add the word this before the first parameter.

The type of the first parameter in your method is the type that the extension method can work against. Let’s change the ForEach method to be an extension method:

public static void ForEach<T>(this IEnumerable<T> collection, Action<T> action) { //ForEach implementation }

Now you can run the ForEach method on every type that implements the IEnumerable<T> interface.

Extension methods are regular methods at their base, and as such, they can receive parameters and return values. Test yourself to see if you can create an extension method that checks whether an integer is even. Here’s my solution:

namespace ExtensionMethodsExample { static class IntExtensions { public static bool IsEven(this int number) { return number % 2 == 0; } } }

As a convention, classes that hold extension methods are named with a suffix of Extensions (such as StringExtensions and CollectionExtensions).

To use the extension method you created, you must add the namespace in which the extension class is declared to the using statements where the calling code is (unless they’re in the same namespace):

using ExtensionMethodsExample; namespace ProgramNamespace { class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { int meaningOfLife = 42; Console.WriteLine("is the meaning of life even:{0}", meaningOfLife.IsEven()); } } }

Working with null

Because extension methods are regular methods, they can work even on null values. Let me show you what I mean. To check whether a string is null or empty, you can use the static method IsNullOrEmpty of String:

string str = ""; Console.WriteLine("is str empty: {0}", string.IsNullOrEmpty(str));

You can create a new extension method that performs the same check on the object itself:

static class StringExtensions { public static bool IsNullOrEmpty(this string str) { return string.IsNullOrEmpty(str); } }

Now you can use it like this:

string str = ""; Console.WriteLine("is str empty: {0}", str.IsNullOrEmpty());

Note that the call is on the variable str itself. Now think about what will happen in this case:

string str = null; Console.WriteLine("is str empty: {0}", str.IsNullOrEmpty());

The code won’t crash, and you can see this message printed:

is str empty: True

That’s pretty neat, even though you execute the IsNullOrEmpty like an instance method, it still runs correctly if there’s no instance. Let’s take this a step further and discuss the way extension methods can help you create fluent interfaces.

3.3.2. Fluent interfaces and method chaining

The term fluent interface was introduced by Eric Evans and Martin Fowler to describe a style of interface that allows subsequent calls of methods. The System.Text.StringBuilder class, for example, provides an interface such as the following:

StringBuilder sbuilder = new StringBuilder(); var result = sbuilder .AppendLine("Fluent") .AppendLine("Interfaces") .AppendLine("Are") .AppendLine("Awesome") .ToString();

StringBuilder offers an efficient way to build strings and provide methods for appending and inserting the substrings into the end result. In the previous code sample, you can keep calling methods on the string builder without adding the variable name until you reach a method that ends the sequence of calls—in this case, ToString. This sequence of calls is also known as method chaining.

With fluent interfaces, you get much more fluid code that feels natural and readable. StringBuilder allows you to create the method chains, because this is how it’s defined. If you look at its methods signature, you’ll see that it returns the type StringBuilder:

public StringBuilder AppendLine(string value); public StringBuilder Insert(int index, string value, int count); : public StringBuilder AppendFormat(string format, params object[] args);

What’s returned from the StringBuilder methods is StringBuilder itself—the same instance. StringBuilder acts as a container of the final string, and every operation changes the internal data structure that forms the final string. Returning the same instance of StringBuilder from the methods allows continuation of the calls.

That’s all good, and we should thank the .NET team for creating such a nice interface, but what happens if the class you need to deal with doesn’t provide such an interface? And what happens if you don’t have access to the source code, and you can’t change it? This is where extension methods come in handy. Let’s look at List<T> as an example.

List<T> provides a method to add items into it:

public class List<T> : IList<T>,... { . . . public void Add(T item); . . . }

The list’s Add method accepts the item you want to add and returns void, so to add items, you have to write it as shown here:

var words = new List<string>(); words.Add("This"); words.Add("Feels"); words.Add("Weird");

You can also omit the variable name to reduce your typing and save energy. First, you’ll create an extension method on the type of List<T> that executes the Add but returns the list afterward:

public static class ListExtensions { public static List<T> AddItem<T>(this List<T> list, T item) { list.Add(item); return list; } }

Now you can add to the list in the fluent way:

var words = new List<string>(); words.AddItem("This") .AddItem("Feels") .AddItem("Weird");

This looks much cleaner, and if you change the this parameter to be more abstract, your extension method will be applicable to more types. You can change the AddItem extension method so you can run it on all collection types that implement the ICollection<T> interface:

public static ICollection<T> AddItem<T>(this ICollection<T> list, T item)

This ability to add methods on abstract types is interesting, because in object-oriented languages, you can’t add method implementation in an interface. If you want all types that implement an interface (such as ICollection) to have a method (such as AddItem), you have to either implement the method yourself in every one of the subtypes or create a shared base-class from which they all inherit. Both alternatives aren’t ideal and sometimes aren’t possible, because you don’t have multiple class inheritance in .NET.[1] Not having multiple inheritance means that if you implement multiple interfaces, each with one or more methods, and you want to share an implementation between all subtypes, you couldn’t make a base class from each interface and inherit from them all. It’s not possible.

A class can implement multiple interfaces even though it can derive from only a single direct base class.

The extension methods, on the other hand, make this ability possible. When you make an extension method on an interface, it’s available on all the types that implement the interface, and if the type implements more interfaces and they have extension methods of their own, the subtype will provide all those methods as well—a kind of virtual multiple inheritance.

It’s important to emphasize that to create a fluent interface, you don’t have to return the same instance or even the same type that the method chain started from. Each method call can return a different type, and the next method call will operate on it.

As you add more and more extension methods on concrete and abstract types, you can use them to create your own language, as you’ll see next.

3.3.3. Creating a language

The extension methods allow you to add new methods on existing types without opening the type code and modifying it. Together with the technique of method chaining, you can build methods that express what you’re trying to achieve in a language that describes your domain.

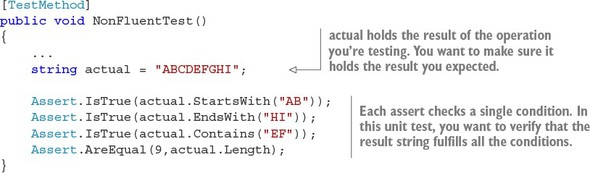

Take the way you write your assertion in unit tests, for example. A unit test is a piece of code that executes code and then asserts that the result was as expected. Here’s a simple test you can write with MSTest to check a string result:

The assertions you use are technical and generic, and you can improve them by using a more fluent interface, such as the one provided by the excellent FluentAssertions library (www.fluentassertions.com). This is the same test after you add FluentAssertion syntax:

[TestMethod] public void FluentTest() { ... string actual = "ABCDEFGHI"; actual.Should().StartWith("AB") .And.EndWith("HI") .And.Contain("EF") .And.HaveLength(9); }

This version of the test checks the same conditions, but uses a much more sentence-like syntax because of the fluent interface. The FluentAssertions library added a DSL for assertions. It does that by adding an extension method for the string type that returns an object with a fluent interface that acts as an assertion builder.

public static StringAssertions Should(this string actualValue);

When the Should method is called, an object of type StringAssertion is created and the string you’re checking is passed to it. From that point, all the assertions are maintained by the StringAssertion.

A DSL, like the one used here for assertions, makes the code concise and declarative. Another important and powerful DSL is the one provided by LINQ that provides generic querying capabilities for collections in .NET.

3.4. Querying collections with LINQ

Extension methods, together with the method-chaining technique, enable you to create DSLs for various domains, even if the original types don’t implement the fluent interface themselves. An area for which a domain language existed for a long time is relational database querying. In relational databases, you can use SQL to query tables in a short and declarative way. Here’s an example of SQL that fetches all the employees who live in the United States, sorted by their last name:

As you can see, the syntax used in SQL is short and declarative; you state the desired result and let the database perform the process of fetching the wanted result for you. Wouldn’t it be great if .NET had the same capability? It does.

LINQ is a set of standard operators that can be used on any data source to make queries. The data source can be an XML document, a database, a string, or any .NET collection. As long as the data source is a class that implements the IEnumerable interface, you can query it using LINQ.

IEnumerable isn’t the only interface that LINQ is targeting. IQueryable is a special interface that makes it possible to evaluate the query against the data source directly so that LINQ queries performed against a database will be translated to SQL.

Figure 3.6 shows the LINQ architecture and its support for various data sources. The way the LINQ architecture is layered makes it possible to write a query once and run it over different sources without any change. The right query “translation” will depend on what the collection really is, but because the collection is abstracted by IEnumerable, you don’t need to know the source that the collection is mapped to.

Figure 3.6. LINQ architecture: for each type of data source, a LINQ provider translates the LINQ query to a query language that best fits the source.

3.4.1. What does LINQ look like?

LINQ is made out of extension methods that operate on the source to build a query. Those methods are generally referred to as operators. Here’s a simple program that uses a LINQ query against a list of integers to find all the odd numbers that are larger than 10 and returns them sorted and without repetitions after adding the value 2 to each one:

The query is performed by creating a method chain of operators, so that each item goes through the operators in the chain one by one and is collected in the final result. The final result is printed as 1337 in our case, because only 35 and 11 will survive the filters and then will be sorted after they’re transformed to 37 and 13. The composability nature of creating the method chains in LINQ is described in the query flow that you see in figure 3.7.

Figure 3.7. Composability of LINQ queries. LINQ is structured as a set of pipes and filters. Conceptually, the output of each operator becomes the input of the next one until you reach the end result.

Using the LINQ operators to create method chains is powerful but not always clear and intuitive. Instead, you can use query expression syntax that provides a declarative syntax resembling the SQL structure. The following example shows the same query from earlier in the chapter, only this time as a query expression:

Note a few things in the example. First, it starts with the from . . . in clause and finishes with select; this is the standard structure. Second, not all operators can be embedded in the query expression syntax like Distinct. You’ll need to add them as method calls inside or outside the query expression. Generally, you can call any method inside the query expression. Eventually, the query expression is syntactic sugar provided by the compiler, but using it makes things much simpler, such as in the case of nested queries and joins.

3.4.2. Nested queries and joins

The query expression syntax enables you to easily create readable nested queries and joins between two collections. Suppose you create a program that takes a collection of books and a collection of authors and displays the name of each author next to the name of that author’s book. This is how you could do it with LINQ:

The query checks each author from the author’s collection against each book in the book collection, similar to a Cartesian product. If the book’s author ID is the same as the author ID, you select a string that says that. The output of this program is as follows:

Tamir Dresher wrote the book: Rx.NET in Action John Skeet wrote the book: C# in Depth John Skeet wrote the book: Real-World Functional Programming

What you did here is a type of grouping, and for that you can use the group operator of LINQ, but that’s beyond the scope of this chapter.

Selecting a string isn’t always what you want; another option is to select the author together with the book inside a new object. But do you need to create a new type each time you want to encapsulate properties together to make simple queries? The answer is no. For that you can use anonymous types.

3.4.3. Anonymous types

One of the great features added to C# as part of the support for LINQ was the ability to create anonymous types. An anonymous type is a type that’s defined in place in your code when its object is created and in advance. The type is generated by the compiler based on the properties you assign to the object. Figure 3.8 shows how to create an anonymous type with two properties, a string and a DateTime.

Figure 3.8. Anonymous type with two properties

The anonymous type is generated by the compiler, and you can’t use it by yourself. The compiler is smart enough to know that if two anonymous types are generated with the same properties, they’re the same type. In our example of finding the authors’ books, you created a string for each author and book pair; instead you can create an object that encapsulates the two properties together:

The anonymous type is visible only in the scope in which it was created, so you can’t return it from a method or send it to another method as an argument unless you cast it to its only base class: object.

Anonymous types are one of the main reasons for the keyword var that’s used to create implicitly typed local variables. Because the anonymous type is generated by the compiler, you can’t create variables of that type; var allows you to make those variables and let the compiler deduce the type, as you see in figure 3.9.

Figure 3.9. Using var on an anonymous type. The compiler and IntelliSense know how to deduce the real type generated.

.NET offers another type that can be used to create bags of properties (which are referred to as items) on the fly: the Tuple<> class. The .NET Framework supports a tuple of up to seven elements, but you can pass eight elements as a tuple so you can get an infinite number of items.

This is how to create a tuple that has two items: a string and a DateTime:

Tuple<string, DateTime> tuple = Tuple.Create("Bugs Bunny", DateTime.Today);

The Tuple.Create factory method can receive arguments as the number of items you wish to have in the tuple.

As with the anonymous type, the Tuple data structure is a generic way to create new types on the fly, but unlike the anonymous type, the access to the Tuple items is based on the position of the item. To read the value on the Tuple you created previously, you need to know that it’s the second item in the tuple:

var theDateTime = tuple.Item2;

This makes the tuple less readable and error prone.

Unlike the anonymous type, Tuple can be returned from a method or passed as an argument, but I advise you to avoid doing so. The better approach in this case is to create a class to serve that purpose and make your code type-safe, readable, and less buggy.

3.4.4. LINQ operators

LINQ operators give LINQ its power and make it attractive. Most of the operators work on collections that implement the IEnumerable<T> interface, which makes it broad and generic. The number of standard query operators is large. It would take more than a chapter to cover them all, so this section presents several of the most commonly used operators. If you find this subject interesting, I recommend that you look at the 101 LINQ Sample on the MSDN site (https://code.msdn.microsoft.com/101-LINQ-Samples-3fb9811b). Rx has always been referred to as LINQ to Events, and, in fact, the LINQ operators were adapted to support observables, so you can expect to see and learn more about those operators in the rest of the book. Table 3.1 presents the ones that I believe are important, clustered by categories that describe their purpose.

Table 3.1. The most used LINQ query operators

3.4.5. Efficiency by deferred execution

LINQ is short and readable, but is it fast? The answer (like most things in programming) is that it depends. LINQ isn’t always the most optimal solution to query a collection, but most of the time you won’t notice the difference. LINQ also works under a deferred execution mode that affects performance and understanding. Consider the next example and try to answer what numbers will print:

The correct answer is that 2, 4, and 6 will print. How can that be? You created the query before adding the number 6; shouldn’t the evenNumbers collection hold only the numbers 2 and 4?

Deferred execution in LINQ means that the query is evaluated only on demand. And demand means when there’s an explicit traversing on the collection (such as foreach) or a call to an operator that does that internally (such as Last or Count).

To understand how deferred execution works, you need to understand how C# uses yield to create iterators.

The yield keyword

The yield keyword can be used inside a method that returns IEnumerable<T> or IEnumerator<T>. When yield return is used inside a method, the value it returns is part of the returned collection, as shown in the following example:

Using yield return and yield break removes the need to manually create iterators by implementing IEnumerable<T> and IEnumerator<T> by ourselves; instead you can put all the logic regarding the creation of each item in a collection inside the method that returns the collection. A classic example is the generation of an infinite sequence such as the Fibonacci sequence. What you’ll do is hold two variables in the method that holds the two previous items in the sequence. With each iteration, you’ll generate a new item by summing the two previous items together and then updating their values:

As you can see, yield can be used inside loops as well as in regular sequential code. The method that contains the yield is controlled from the outside. Each time the MoveNext method is called on the Enumerator of the output IEnumerable, the method that returned the IEnumerable is resumed and continues its execution until it reaches the next yield statement or until it reaches its end. Behind the scenes, the compiler generated a state machine that keeps track of the method’s position and knows how to transition to the next state to continue execution.

The LINQ operators (most of them) are implemented as iterators, so their code is executed lazily on each item in the collection queried. Here’s a modified version of the Where operator to explain that point. The modified Where prints a message for each item it checks:

static class EnumerableDefferedExtensions { public static IEnumerable<T> WhereWithLog<T>(this IEnumerable<T> source, Func<T, bool> predicate) { foreach (var item in source) { Console.WriteLine("Checking item {0}", item); if (predicate(item)) { yield return item; } } } }

Now you’ll use WhereWithLog on a collection and validate that the predicate isn’t used on all the items at once but in an iterative way:

var numbers = new[] { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 }; var evenNumbers = numbers.WhereWithLog(x => x%2 == 0); Console.WriteLine("before foreach"); foreach (var number in evenNumbers) { Console.WriteLine("evenNumber:{0}",number); }

This is the output:

before foreach Checking item 1 Checking item 2 evenNumber:2 Checking item 3 Checking item 4 evenNumber:4 Checking item 5 Checking item 6 evenNumber:6

You can see that between each item yielded, a message is printed from the outer foreach loop. When you build a method chain of LINQ operators, each item moves through all the operators and is then handled by the code that traverses the query result, and then the next item goes through the chain.

The deferred execution has a good impact on performance. If you need only a limited number of items from a query result, you’re not paying for the query execution time on the items you don’t care for.

The deferred execution also allows you to build queries dynamically, because the query isn’t evaluated until you iterate on it. You can add more and more operators without causing side effects:

3.5. Summary

C# was introduced in 2002 as an object-oriented language. Since then, C# has collected features and styles from other languages and became a multi-paradigmatic language.

- The functional programming styles aim to create a declarative and concise code that’s short and readable.

- Using techniques such as a declarative programming style, first-class functions, and concise coding that were adopted by C# can make you more productive.

- In C# you use delegates to provide the first-class and higher-order functions.

- The reusable Action and Func types helps you express functions as parameters.

- Anonymous methods and lambda expressions make it easy to consume those methods and send code as arguments.

- In C#, you use a method-chaining technique to build domain-specific languages (DSLs) that express the domain you program.

- Extension methods make it easy to add functionality to types when you don’t have access to a type source code or when you don’t want to modify their code.

- To accomplish method chaining, use fluent interfaces and extension methods.

- LINQ makes querying over a collection super easy, with an abstraction that allows executing the same query against different underlying repositories.

- You can use LINQ to make simple queries that filter collections and more--complex queries that involve joining two collections together.

- Anonymous types ease your querying because it provides they provide inline creation of types that you use to store the results of your queries that should be visible only inside a scope.

- Deferred execution allows you to create queries that are executed when the results of the query are used instead of when the query is created

The next chapter discusses the first part of creating an Rx query and the basics of creating the observables that every Rx query is built upon.