Chapter 4. Creating observable sequences

- Creating observables of data and events

- Creating observables from enumerables

- Using Rx creational operators

- Getting to know the primitive observables

When people start learning about Rx, they usually ask, “Where do I begin?” The answer is easy: you should start with creating the observable.

In the next two chapters, you’ll learn various ways to create observables. This chapter is limited to observables that are synchronous in their creation. Chapter 5 covers observables that involve asynchroncity in their creation and emissions.

Because many types of sources exist from which you want to receive items, it’s not surprising that you have more than one way to create an observable. For instance, you can create an observable from traditional .NET events so you can still reuse your existing code, or you can create it from collections of items so it’s easier to combine it with other observables. Each way is suited to different scenarios and has different implications, such as simplicity and readability.

4.1. Creating streams of data and events with observables

The IObservable interface is the most fundamental building block that Rx is based on, and it includes only a single method: Subscribe.

The observable is the source that pushes the items, and on the other end is the observer that receives them. The items can be of many forms: they can be the notification that something happened (events) or a data element you can process like a chat message.

Figure 4.1 shows an observable that represents a stream of chat messages received by a chat application. The chat observer receives each message through the OnNext method, and can display it on-screen or save it to a database. At one point, a network disconnection leads to an error notification.

Figure 4.1. An example of a possible observable-observer dialogue. The observer receives notifications after subscribing until the network disconnects, which leads to an error.

We’ll discuss a few ways to get to this type of observable. We’ll start with the naïve solution.

4.1.1. Implementing the IObservable<T> interface

Before getting into a heavy chat message example, let’s look at listing 4.1, which shows the most simple and naïve way to create an observable that pushes a simple series of numbers to observers: manually implementing the IObservable<T> interface. Creating observables this way isn’t the best practice, but I believe it’s essential for understanding the mechanics of how observables work.

Listing 4.1. Handcrafted observable that pushes numbers

The NumbersObservable class implements the IObservable interface, which allows any observer of integers to subscribe to it. Note that the NumbersObservable pushes the integer values immediately and synchronously as the observer subscribes to it. We’ll talk later about observables that make asynchronous execution.

The following listing is an example of an observer that will accompany us throughout the chapter. This observer writes to the console the OnNext, OnComplete, and OnError actions as they happen.

Listing 4.2. ConsoleObserver writes the observer actions to the console

The following shows how to subscribe the ConsoleObserver to the Numbers-Observable:

var numbers = new NumbersObservable(5); var subscription = numbers.Subscribe(new ConsoleObserver<int>("numbers"));

If you run the code snippet, this is what you’ll see:

numbers - OnNext(0) numbers - OnNext(1) numbers - OnNext(2) numbers - OnNext(3) numbers - OnNext(4) numbers - OnCompleted()

The five numbers that the observables pushed to the observer are displayed in the line with OnNext, and after the observable completed, so the last line is the call to On-Completed.

Whenever an observer is subscribed to the observable, the observer receives an object that implements the IDisposable interface. This object holds the observer’s subscription, so you can unsubscribe at any time by calling the Dispose method. In our simple example that emits a series of numbers, the entire communication between the observable and the observer is done in the Subscribe method, and when the method ends, so does the connection between the two. In this case, the subscription object doesn’t have real power, but to keep the contract correct, you return and empty the disposable by using the Rx static property Disposable.Empty.

Note

Appendix B covers the Rx Disposables library in more detail.

You can make the subscription of ConsoleObserver more user friendly. Instead of creating an instance and subscribing each time you need it, let’s create an extension method that does that for you.

Listing 4.3. SubscribeConsole extension method

public static class Extensions { public static IDisposable SubscribeConsole<T>( this IObservable<T> observable, string name="") { return observable.Subscribe(new ConsoleObserver<T>(name)); } }

SubscribeConsole will help you throughout this book, and it may be useful for your Rx testing and investigations, so it’s a good tool to have. The previous example now looks like this:

![]()

You’ve now created an observable and observer by hand, and it was easy. Why, then, can’t you always do it this way?

4.1.2. The problem with handcrafted observables

Writing observables by hand is possible, but rarely used, because creating a new type each time you need an observable is cumbersome and error prone. For example, the observable-observer relation states that when OnCompleted or OnError are called, no more notifications will be pushed to the observer. If you change the Numbers-Observable you created and add another call to the observer OnNext method after OnComplete is called, you’ll see that it’s called:

This code now causes your ConsoleObserver to output the following:

errorTest - OnNext(0) errorTest - OnNext(1) errorTest - OnNext(2) errorTest - OnNext(3) errorTest - OnNext(4) errorTest - OnComplete errorTest - OnNext(5)

This is problematic because the unwritten agreement between the observable and the observer is what allows you to create the various operators of Rx. The Repeat operator, for example, resubscribes an observer when the observable completes. If the observable lies about its completion, the code that uses Repeat becomes unpredictable and confusing.

4.1.3. The ObservableBase

You don’t often write observables manually, but doing so does make sense in some cases. For example, when you want to name your observable and make it encapsulate complex logic, then a handcrafted observable is good for you. Say you need to create a mapping of what goes into each of the observer methods (as you’ll see next when you use a chat service that you talk to), but the service client is represented by a class that provides events for different types of notifications. In this case, you’d like to consume the chat service with an observable that pushes chat messages. When connecting to the chat service, you get a connection object with the following interface:

The connection to the chat service is done using the Connect method of the ChatClient class:

public class ChatClient { ... public IChatConnection Connect(string user, string password) { // Connects to the chat service } }

It’s much nicer to consume the chat messages with an observable. The mapping, shown in figure 4.2, is clear between the events and what the observer knows to handle:

- Received event can be mapped to the observers’ OnNext

- Closed event can be mapped to the observers’ OnComplete

- Error event can be mapped to the observers’ OnError

Figure 4.2. Mapping the ChatConnection events to the observer methods

Because logic is involved in wiring the event to the observer method, creating your own observable type makes sense. But you still want to avoid the common pitfalls of creating observables manually, so the Rx team provides a base class: ObservableBase. The following listing shows how to use it to create the Observable-Connection class.

Listing 4.4. ObservableConnection

Tip

The ObservableConnection example is based on the way SignalR creates its observable connection. SignalR is a library that helps server-side code push content to the connected clients. It’s powerful, so you should check it out.

ObservableConnection derives from ObservableBase<string> and implements the abstract method SubscribeCore, which is called from the ObservableBase Subscribe method. ObservableBase performs a validity check on the observer for you (in case of null) and enforces the contract between the observer and the observable. It does that by wrapping each observer inside a wrapper called AutoDetachObserver. This wrapper automatically detaches the observer from the client when the observer calls OnCompleted or OnError or when the observer itself throws an exception while receiving the message. This takes away the burden of implementing this safe execution pipeline yourself in your observables.

After you get the ObservableConnection, you can subscribe to it:

As before, you can make the creation of the ObservableConnection more pleasant with an extension method.

Listing 4.5. Creating the ObservableConnction with an extension method

public static class ChatExtensions { public static IObservable<string> ToObservable( this IChatConnection connection) { return new ObservableConnection(connection); } }

Now, you can simply write this:

var subscription = chatClient.Connect("guest", "guest") .ToObservable() .SubscribeConsole();

Still, it’s annoying to create new observable types each time, and most of the time you don’t have such complex logic to maintain. That’s why it’s considered bad practice to create observables by deriving directly from the ObservableBase or the IObservable interface. Instead, you should use one of the existing factory methods for observable creation that the Rx library provides.

4.1.4. Creating observables with Observable.Create

Every observable implements the IObservable interface, but you don’t have to do it manually. The static type Observable that’s located under the System.Reactive.Linq namespace provides several static methods to help you create observables. The Observable.Create method allows you to create observables by passing the code of the Subscribe method. The following listing shows how to use it to create the numbers observable you manually created previously.

Listing 4.6. Creating the numbers observable with Observable.Create

As with the ObservableBase you used previously, the Create method does all the boilerplate for you. It creates an observable instance—of type AnonymousObservable—and attaches the delegate you provided (as a lambda expression, in this case) as the observable Subscribe method.

Observable.Create takes it even further, and allows you to return not only an IDisposable that you create, but also an Action. The provided Action can hold your cleanup code, and after it returns, the Create method will wrap the Action inside an IDisposable object that it creates by using Disposable.Create. If you return null, Rx will create an empty disposable for you.

Note

Appendix B covers the Rx Disposables library in more detail.

Of course, you’d want your observable created with a user-defined amount and a static number of items (five in the previous example). Create the observable inside a method, as shown here:

Observable.Create is heavily used because it’s flexible and easy to use, but you may wish to postpone the creation of the observable until it’s needed, such as when the observer is subscribed.

4.1.5. Deferring the observable creation

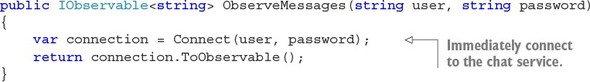

In section 4.1.2, you used the ChatClient class to connect to a remote chat server and then converted the returned ChatConnection into an observable that pushed the messages into the observers. The two steps of connecting to the server and then converting the connection to the observable always come together, so you want to add the method ObserveMessages to the ChatClient, encapsulate it, and follow the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle:

Whenever a call to the ObserveMessages method is made, a connection to the chat service is created and then it’s converted to an observable. This works perfectly fine, but it’s possible that after the observable is created, no observer is subscribed to it for a long time or no observer ever subscribes. One reason this could happen is that you may create an observable and pass it to other methods or objects that might use it in their own time (for example, a screen that subscribes only when it’s loaded, but loads only when a parent view receives input from a user).

Yet the connection is open and wastes resources on your machine and on the server machine. It would be better to delay the connection to the moment the observer subscribes. This is the purpose of the Observable.Defer operator that has the signature shown in figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3. The Defer method signature

The Defer operator creates an observable that acts as a proxy around the real observable. When the observer subscribes, the observableFactory function that was provided as an argument is called and the observer subscribes to the created observable. This sequence is shown in figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4. Sequence diagram of the subscription of an observer to a deferred observable created with the Defer operator.

Defer is good when you want to create observables with any of the observable factory operators you’ll learn next, or if you have a factory method of your own (that you might, can’t, or don’t want to change), but you still want to create that observable when the observer subscribes.

This is how to use Defer to create the ObservableConnection:

public IObservable<string> ObserveMessagesDeferred(string user, string password) { return Observable.Defer(() => { var connection = Connect(user, password); return connection.ToObservable(); }); }

I should point out that using Defer doesn’t mean that the observable that was created with the observableFactory is shared between multiple observers. If two observers subscribe to the observable that was returned from the Defer method, the Connect method will be called twice:

![]()

This behavior isn’t specific to Defer. The same issue occurred in the observables you created previously. Keep that in mind, and you’ll learn when and how to make shareable observables in chapter 6 when we talk about cold and hot observables. Defer also plays another role in the observables “temperature” world because it can be used to turn a hot observable to a cold one, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Eventually, the observable you created bridged traditional .NET events into the Rx. This is something you often do with Rx, so Rx provides operators that ease that work.

4.2. Creating observables from events

Creating an observable from a traditional .NET event is something you’ve seen in previous chapters, but we haven’t discussed what happens inside. If all you need is to convert a traditional .NET event to an observable, using methods such as Observable.Create will be excessive. Instead, Rx provides two methods to convert from event to observable, namely FromEventPattern and FromEvent. These two methods (or operators) often lead to confusion for people working with Rx, because using the wrong one will cause compilation errors or exceptions.

4.2.1. Creating observables that conform to the EventPattern

The .NET events that you see inside the .NET framework expect the event handler to have the following signature:

void EventHandler(object sender, DerivedEventArgs e)

The event handler receives an object that’s the sender that raised the event, and an object of a type that derives from the EventArgs class. Because the pattern of passing sender and eventargs is so commonly used, you can find generic delegates in the .NET Framework that you can use when creating events: EventHandler and Event-Handler<T>.

Rx recognizes that it’s common to create events with delegates of that structure, which is called the event pattern, and therefore provides a method to convert events that follow the event pattern easily. This is the FromEventPattern operator. FromEventPattern has a few overloads, and the most used one is shown in figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5. One of the FromEventPattern method overload’s signatures

The addHandler and removeHandler parameters are interesting. Because they let you specify how to attach and detach the inner event handler that Rx provides, they expect to get an action that performs the registration and deregistration of a delegate (that’s provided as the action parameter) from the event. In most cases (if not all), they have the following form:

- addHandler → h => [src].[event] += h

- removeHandler → h => [src].[event] -= h

For example, one of the places you see the event pattern is in UI events, such as in WPF. Suppose you want to receive the stream of clicks on a button named theButton that’s placed in a window. The Button class exposes the Click event (that’s defined in its base class ButtonBase):

public event RoutedEventHandler Click;

The RoutedEventHandler is a delegate that’s defined in the System.Windows namespace:

public delegate void RoutedEventHandler(object sender, System.Windows.RoutedEventArgs e)

To create an observable from the click event, write the following code:

Here, you convert the Click event to an observable, so that every event raised will call the observers’ OnNext method. You specify that the generic parameters are Routed-EventHandler, because this is the event handler specified in the event definition, and RoutedEventArgs, because this is the eventargs type that the event sends to the event handlers.

The created observable pushes objects of type EventPattern<RoutedEvent-Args>. This type encapsulates the values of the sender and the eventargs.

If the event is defined using the standard EventHandler<TEventArgs>, you can use the FromEventPattern overload that expects only the generic parameter of TEventArgs:

Rx also gives the simplest version for converting events into observables, in which you need to specify only the name (as a string) of the event and the object that holds it, so the click event example could’ve been written as follows:

IObservable<EventPattern<object>> clicks = Observable.FromEventPattern(theButton, "Click");

I’m not fond of this method. Magic strings tend to cause all sorts of bugs and code confusion.[1] It’s easy to make a typo, and you need to remember to change the strings around your application in case you decide to rename your event. But the simplicity is attractive, so use it with care.

A possible solution to the magic strings problem is the nameof operator that has existed since C# 6.0. See https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dn986596.aspx.

Tip

If you’re working with GUI applications and find the conversion between UI events to observables appealing, you might find the ReactiveUI framework (http://reactiveui.net/) helpful. ReactiveUI isn’t covered in this book, but it provides many useful Rx utilities. One of them is the built-in conversions of many UI events to observables.

4.2.2. Events that aren’t following the event pattern

Not all events follow the event pattern. Suppose you have a class that scans the available Wi-Fi networks in your area. The class exposes an event that’s raised when a network become available:

public delegate void NetworkFoundEventHandler(string ssid); class WifiScanner { public event NetworkFoundEventHandler NetworkFound = delegate { }; // rest of the code }

The event doesn’t follow the standard event pattern because the event handler needs to receive a string (for the network SSID). If you try to convert the event to an observable by using the FromEventPattern method, you’ll get an argument exception, because the NetworkFoundEventHandler delegate isn’t convertible to the standard EventHandler<TEventArgs> type.

To overcome this, Rx provides the FromEvent method that looks similar to the FromEventPattern method:

IObservable<TEventArgs> FromEvent<TDelegate, TEventArgs> (Action<TDelegate> addHandler, Action<TDelegate> removeHandler);

This overload of the FromEvent method gets two generic parameters: one for the delegate that can attach to the event, and another for the type of the eventargs that’s passed to the delegate by the event. The important part here is that you have no constraint on the type of the delegate or on the eventargs; they can be whatever you like. This is how to write the WifiScanner class:

var wifiScanner = new WifiScanner(); IObservable<string> networks = Observable.FromEvent<NetworkFoundEventHandler, string>( h => wifiScanner.NetworkFound += h, h => wifiScanner.NetworkFound -= h);

In the code, you create an observable from the event that the WifiScanner exposes. The event expects an eventHandler that conforms to the NetworkFoundEvent-Handler delegate, and the value that the event handlers receives is string, so the resulting observable is of type IObservable<string>.

4.2.3. Events with multiple parameters

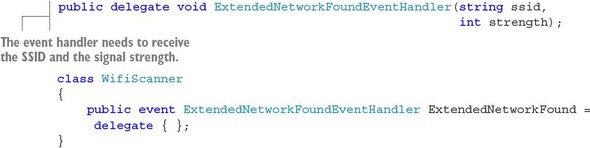

The more complex overload of the FromEvent method is used when the event you want to convert to an observable has more than one parameter in the eventHandler signature. Take, for example, the case that the WifiScanner is sending not only the network name, but also its strength:

Trying to write the same code you wrote for the one parameter version won’t work. Observables can pass only one value when they call the OnNext method of their observers. You need to somehow wrap the two parameters in a single object. The FromEvent overload that you’ll use takes a conversion function that converts the Rx event handler to an event handler that can be used with the event. First, let’s look at the method signature and then I’ll explain what exactly you’re seeing.

This method signature takes time to digest, so I’ll explain it with an example to help you understand. The following example converts the ExtendedNetworkFound event into an observable of Tuple<string, int>:

First let’s talk about addHandler and removeHandler. As before, this pair of actions receives a reference to a method that can be registered to the event in question. The addHandler registers it, and the removeHandler unregisters it. But how does Rx know what handler to create? This is the job of the conversion function. In the previous example, the conversion function is the lambda expression. Its purpose is to create a handler of its own that has the signature of the delegate defining the event. The lambda expression receives the parameter rxHandler, which holds the method that eventually calls the OnNext method in the observers. The lambda expression builds the event handler that can be registered to the ExtendedNetworkFound event; this event handler calls rxHandle, and so it acts as a mediator between what the event expects and what Rx expects.

4.2.4. Dealing with events that have no arguments

Not every event sends arguments to its event handlers. Certain events state that something happens; for example, the next event is raised by your WiFiScanner when the network connects:

event Action Connected = delegate { };

When trying to convert the event to an observable, you face a problem. Every observable must implement IObservable<T>, and T is the type of the data that will be pushed to the observers. What will type T be for the observable created from the Connected event? You need a neutral type that could represent a void. In mathematics, a neutral element with respect to an operation (such as multiplication or addition) is called the Unit (it’s really called the Identity element, but under a broader context it’s referred to as the Unit). You’re already familiar with the Unit element in your day-to-day life: it’s the number 1 under multiplication, and 0 under addition. That’s why Rx includes the struct System.Reactive.Unit. This struct has no real members, and you can think of it as an empty entity that represents a singular value. It’s often used to denote the successful completion of a void-returning method, as in the case of our event. This how to convert your event to an observable:

IObservable<Unit> connected = Observable.FromEvent( h => wifiScanner.Connected += h, h => wifiScanner.Connected -= h); connected.SubscribeConsole("connected");

Because Unit has only a default value (that represents void), its ToString methods return the string of empty parentheses “()”, so the following output is what you’ll get from the previous example:

connected - OnNext(()) connected - OnNext(())

Note

We didn’t cover a few of the overloads to FromEventPattern and FromEvent. Those overloads allow you to simplify hooking events for simple cases (when the event handler is just Action<T>, for example) or to convert from an event that doesn’t conform to the event pattern into IObservable of EventPattern. You should take a look.

Converting events into observables can be helpful, because after you have the observable, there’s no limit to the event processing you can do with Rx operators. But events aren’t the only constructs you’d like to convert to an observable; sometimes you’ll want to take something that’s the complete opposite of an observable and turn it into an observable. I’m talking about enumerables.

4.3. From enumerables to observables and back

Enumerables provide the mechanism to work in a pull model, whereas observables enable you to work in a push model. Sometimes you’ll want to move from a pull model to a push model to create a standard handling of both worlds, such as creating the same logic for adding chat messages that are received on the fly and for messages that were stored and read later from a repository. Sometimes it might even make sense to move from a push model to a pull model. This section explores those transitions and their effects on your code.

4.3.1. Enumerable to observable

Enumerables and observables are dual; you can go from one to the other by following several simple steps. Rx provides a method that helps you convert an enumerable into an observable: ToObservable. In this example, you create an array of strings and convert it to an observable:

IEnumerable<string> names = new []{"Shira", "Yonatan", "Gabi", "Tamir"}; IObservable<string> observable = names.ToObservable(); observable.SubscribeConsole("names");

If you run this code, the following is printed:

names - OnNext(Shira) names - OnNext(Yonatan) names - OnNext(Gabi) names - OnNext(Tamir) names - OnCompleted()

Under the hood, the ToObservable method creates an observable that, once subscribed into, iterates on the collection and passes each item to the observer. When the iteration is done, the OnComplete method is called on the observer.

If an exception occurs while iterating, it will be passed to the OnError method.

Listing 4.7. Creating an observable that throws

The output of this example is as follows:

enumerable with exception - OnNext(1)

enumerable with exception - OnNext(2)

enumerable with exception - OnNext(3)

enumerable with exception - OnError:

System.ApplicationException: Something Bad Happened

. . .

If all you need is to eventually subscribe to the enumerable, you can use the Subscribe extension method on the enumerable. This converts the enumerable to an observable and subscribes to it:

IEnumerable<string> names = new[] { "Shira", "Yonatan", "Gabi", "Tamir" }; names.Subscribe(new ConsoleObserver<string>("subscribe"));

Where to use it

At the beginning of this chapter, you created an ObservableConnection that helped you consume chat messages through an observable. The nature of the ObservableConnection is that only new messages will be received by the client, but as users, you’d like to enter the chat room and see the messages that were there before you connected.

For the simplicity of our scenario, let’s assume that while you were offline, no messages were sent. This leaves the problem of loading the messages saved from all the previous sessions. Usually, this is where a database is needed. Your application is saving every message it receives into a database, and when you connect, those messages are loaded and added to the messages screen.

With the ObservableConnection, you already have code that knows how to add messages to the screen. This is code you’d also like to use for the messages loaded from the database. It would’ve been great to represent the messages in the database as an observable, merge it with the observable of the new messages, and use the same observer to receive the messages from both worlds. Here’s a small example that does that: two messages are saved to the database, and two messages are received while connected:

This example uses the operator Concat. This operator will concatenate the liveMessages observable to the loadedMessages observable, such that, only after all the loaded messages are sent to the observers, the live messages will be sent. The following is the output:

merged - OnNext(loaded1) merged - OnNext(loaded2) merged - OnNext(live message1) merged - OnNext(live message2)

You could write the same example without converting the enumerable by yourself:

liveMessages

.StartWith(loadedMessages)

.SubscribeConsole("loaded first");

The StartWith operator first sends to the observers all the values in the enumerable and then starts to send all messages received on the liveMessages observable.

In the previous chapters, where we talked about the enumerable/observable duality, you saw that it allows going in both directions, from enumerable to observable, as you saw here, and from observable to enumerable, as you’ll see next.

4.3.2. Observable to enumerable

In the same way that you converted an enumerable to an observable, you can do the opposite, using the ToEnumerable methods. This creates an enumerable that, once traversed, will block the thread until an item is available or until the observable completes. Using ToEnumerable isn’t something that you want to do, but sometimes can’t do otherwise, as in the cases when you have a library code that accepts only enumerables and you need to use it on a known subset of items from the observable, for example, sorting a fraction of items that you can define by time or amount. Using ToEnumerable is simple, as you’ll see here.

Listing 4.8. Using the ToEnumerable operator

Because of the blocking behavior of the enumerable returned from ToEnumerable, using it isn’t recommended. You should stay with the push model as much as possible.

Note

The Next operator also returns an enumerable, but it acts differently than the one ToEnumerable is returning. Chapter 6 covers this topic.

Rx includes methods that can convert the observable to a list and an array in a nonblocking way (keeping it an observable), namely ToList and ToArray, respectively. Unlike ToEnumerable, these methods return an observable that provides a single value (or no value if an error occurs), which is the list or the array. The list (or array) is sent to the observers only when the observable completes.

Listing 4.9. Using the ToList operator

Running this sample results in this output:

list ready - OnNext(Observable,To,List) list ready - OnCompleted()

In the spirit of converting an observable to an enumerable, I should also mention the ToDictionary and ToLookup methods. Though they sound similar, they have different use cases.

Converting an observable to a dictionary

In .NET, types that implement the interface System.Collections.Generic.IDictionary<TKey, TValue> are said to be types that contain key-value pairs. For each key, there can be only one corresponding value or no value at all. In this case, we say the key isn’t part of the dictionary.

Rx provides a way to turn an observable into a dictionary, by using the method ToDictionary that has a few overloads. The following example is the simplest one:

This method runs keySelector for each value that’s pushed by the source observable and adds it to the dictionary. When the source observable completes, the dictionary is sent to the observers. Here’s a small example that demonstrates how to create a dictionary from city names, where the key is the name length.

Listing 4.10. Using the ToDictionary operator

Running the example displays the following:

dictionary - OnNext([6, London],[8, Tel-Aviv],[5, Tokyo],[4, Rome]) dictionary - OnCompleted()

If the two values in the observable share the same key, when trying to add them to the dictionary you’ll receive an exception that says the key already exists. Dictionaries maintain a 1:1 relationship between the key and the value; if you want multiple values per key, you need a lookup.

Converting an observable to a lookup

If you need to convert your observable into a dictionary-like structure that holds multiple values per key, ToLookup is what you need. The ToLookup signature looks similar to the signature of ToDictionary:

IObservable<ILookup<TKey, TSource>> ToLookup<TSource, TKey>( this IObservable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, TKey> keySelector)

As with ToDictionary, you need to specify the key for each observable value (other overloads allow you to also specify the value itself). You can look at the lookup as a dictionary in which each value is a collection.

The next example creates a lookup from an observable of city names, where the key is the length of the name. This time, the observable will have multiple cities with the same name length.

Listing 4.11. Using the ToLookup operator

This is the output after running the example:

lookup - OnNext([Key:6 => 2][Key:8 => 1][Key:5 => 1][Key:4 => 1]) lookup - OnCompleted()

You can see that because London and Madrid have the same length (of 6), the output shows that the key 6 has two values.

The duality between observables and enumerables allows you to operate in both worlds and makes it easy for you to transform one to the other according to your needs. But remember that it comes with a warning. You have more ways to create observables than “implementing” their logic or converting from other types. Common patterns are nicely abstracted with creational operators and can be used as factories.

4.4. Using Rx creational operators

Up to this point, you’ve seen how to create observables by hand or convert from known types such as enumerables and events. Over time, it’s become clear that certain patterns in the observable creation are being repeated, such as emitting items inside a loop or emitting a series of numbers. Instead of writing it ourselves, Rx provides operators that help do it in a standard and concise way. The observables created by the creational operators are often used as building blocks in much more complex observables.

4.4.1. Generating an observable loop

Suppose you have an iterative-like process that you need to run to produce the observable sequence elements a few lines at a time, as in the case of reading a file in batches. For this type of scenario, you can use the Observable.Generate operator. Here’s its simplest overload:

For example, if you want to generate an observable that pushes the first 10 even numbers (starting from 0), this is how you do it:

IObservable<int> observable = Observable.Generate( 0, //Initial state i => i < 10, //Condition (false means terminate) i => i + 1, //Next iteration step i => i*2); //The value in each iteration observable.SubscribeConsole();

Running this example prints the numbers 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18.

To make this even simpler, if what you’re trying to create is an observable that creates a range of elements, you can use another operator that does only that: the Observable.Range operator:

IObservable<int> Range(int start, int count)

This creates an observable that pushes the integral numbers within a specified range.

If you add the Select operator, you can create the same observable you created by using Generate:

Generate or Range can be used to create more than numbers generators. Here’s an example that uses Generate to create an observable that emits the lines of a file.

4.4.2. Reading a file

Basically, reading a file is an iterative process. You need to open the file and read line by line until you reach the end. In the observable world, you’d like to push the content to your observers. The following code shows how to do that with Observable.Generate:

This is what I got when running the example on a file with four lines:

lines - OnNext(The 1st line) lines - OnNext(The 2nd line) lines - OnNext(The 3rd line) lines - OnNext(The 4th line) lines - OnCompleted()

Freeing the file resource

The previous example has a flaw you may not see immediately. The call to File.OpenText creates a stream that holds the file open. Even after the observable completes—either when it reaches the end or when it is disposed of from the outside—the stream is still active and the file remains open. To overcome this and so that your application will handle resources correctly, you need to let Rx know that a disposable resource is involved. This is where the Observable.Using operator fits in. The Using operator receives a factory method that creates the resource (and the factory method that creates the observable with that resource). The returned observable will make sure that when the inner observable completes, the resource will be disposed of.

Note

The Using operator, together with other resource management considerations, is covered in chapter 10.

This listing shows how to correct our example.

Listing 4.12. Freeing resources with the Using operator

Now you know for sure that when your observable is used, no resource you create will remain undisposed, which makes your code more efficient.

4.4.3. The primitive observables

A few creational operators can come in handy during certain times, to combine with other observables to create edge cases. This can be useful when testing or for demonstrations and learning purposes, but also when building operators of your own that need to deal with certain inputs that require special handling.

Creating a single-item observable

The Observable.Return operator is used to create an observable that pushes a single item to the observer and then completes:

Observable.Return("Hello World") .SubscribeConsole("Return");

Running this example results in this output:

Return - OnNext(Hello World) Return - OnCompleted()

Creating a never-ending observable

Observable.Never is used to create an observable that pushes no items to observers and never completes (not even with an error):

Observable.Never<string>() .SubscribeConsole("Never");

The generic parameter is used to determine the observable type. You can also pass a fake value of the type you want to do the same. Running this example prints nothing on the screen.

Creating an observable that throws

If you need to simulate a case that an observable notifies its observers about an error, Observable.Throw will help you do this:

Observable.Throw<ApplicationException>( new ApplicationException("something bad happened")) .SubscribeConsole("Throw");

This is what prints after running the example:

Throw - OnError:

System.ApplicationException: something bad happened

Creating an empty observable

If you need an observable that doesn’t push any items to its observers and completes immediately, you can use the Observable.Empty operator:

Observable.Empty<string>() .SubscribeConsole("Empty");

This prints the following:

Empty - OnCompleted()

4.5. Summary

Wow, you learned a lot in this chapter. You should feel proud of yourself. The material covered in this chapter will be carried with you in almost every observable pipeline you’ll create:

- All observables implement the IObservable<T> interface.

- Creating observables by manually implementing the IObservables interface is discouraged. Instead, use one of the built-in creation operators.

- The Create operator allows you to create observables by passing the Subscribe method that will run for each observer that subscribes.

- The Defer operator allows you to defer or delay the creation of the observable until the time when an observer subscribes to the sequence.

- To create an observable from events that conform to the event pattern (where the delegate used receives a sender and EventArgs), use the FromEvent-Pattern operator.

- To convert events that don’t conform to the event pattern, use the FromEvent operator.

- The FromEventPattern and FromEvent operators receive a function that adds an event handler to the event, and a function that removes an event handler from the event.

- You can use an overload of the FromEventPattern operator that allows you to pass an object and to specify the name of the event to create the observable from. This should be used mostly for standard framework events.

- Enumerables can be converted to observables as well using the operator To-Observable.

- Observables can be converted to enumerables by using the operators To-Enumerable, ToList, ToDictionary, and ToLookup. But they’ll cause the consuming code to block until an item is available or until the entire observable is completed, depending on the operator.

- To create an observable from an iterative process, use the Generate operator.

- The Range operator creates an observable that emits the sequence of numbers in the specified range.

- To create an observable that emits one notification, use the Observable.Return operator.

- To create an observable that never emits notifications, use the Observable.Never operator.

- To create an observable that notifies failure, use the Observable.Throws operator.

- To create an empty observable, use the Observable.Empty operator.

Still, throughout the chapter, we ignored important types that wrap asynchronous execution. The next chapter will extend your knowledge about creating observables. You’ll learn about the asynchronous patterns in .NET and how to bridge them into Rx.