- What an automated test is

- The goal of writing automated tests

- How automated tests can help you write better code, in less time, with more confidence

When everything runs on software, from your uncle’s bakery to the country’s economy, the demand for new capabilities grows exponentially, and the more critical it becomes to ship software that works and ship it frequently—hopefully, multiple times a day. That’s what automated tests are here for. Long gone is the time when programmers could afford themselves the luxury of manually testing their software every once in a while. At this point, writing tests is not only good practice, it’s an industry standard. If you search job postings at this very moment, almost all of them require some degree of knowledge about automated software testing.

It doesn’t matter how many customers you have or the volume of data you deal with. Writing effective tests is a valuable practice for companies of every size from venture-capital-backed Silicon Valley giants to your own recently bootstrapped startup. Tests are advisable for projects of all sizes because they facilitate communication among developers and help you avoid defects. Because of these reasons, the importance of having tests grows proportionally to the number of developers involved in a project and to the cost of failure associated with it.

This book is targeted at professionals who can already write software but can’t yet write tests or don’t know why it’s critical to do so. While writing these pages, I had in mind people who are fresh out of bootcamps or recently got their first development job and want to grow into seniority. I expect readers to know the basics of JavaScript and understand concepts like promises and callbacks. You don’t need to be a JavaScript specialist. If you can write programs that work, that’s enough. In case the shoes fit, and you’re concerned about producing the most valuable kind of software—software that works—this book is for you.

This book is not targeted at quality assurance professionals or nontechnical managers. It covers topics from a developer’s point of view, focusing on how they can use tests’ feedback to produce higher-quality code at a faster pace. I will not talk about how to perform manual or exploratory testing, nor about how to write bug reports or manage testing workflows. These tasks can’t be automated yet. If you want to learn more about them, it’s advisable to look a book targeted at QA roles instead.

Throughout the book, the primary tool you will use is Jest. You will learn by writing practical automated tests for a few small applications. For these applications, you’ll use plain JavaScript and popular libraries like Express and React. It helps to be familiar with Express, and especially with React, but even if you are not, brief research should suffice. I’ll build all of the examples from scratch and assume as little knowledge as possible, so I recommend to research as you go instead of doing so up-front.

In chapter 1, we’ll cover the concepts that will permeate all further practice. I find that the single most prominent cause of bad tests can be traced back to a misunderstanding of what tests are and what they can and should achieve, so that’s what I’m going to start with.

Once we have covered what tests are and the goal of writing them, we will talk about the multiple cases where writing tests can help us produce better software in less time and facilitate collaboration among various developers. Having these conceptual foundations will be crucial when we start writing our first tests in chapter 2.

1.1 What is an automated test?

Uncle Louis didn’t stand a chance in New York, but in London, he’s well-known for his vanilla cheesecakes. Because of his outstanding popularity, it didn’t take long for him to notice that running a bakery on pen and paper doesn’t scale. To keep up with the booming orders, he decided to hire the best programmer he knows to build his online store: you.

His requirements are simple: customers must be able to order items from the bakery, enter the delivery address, and check out online. Once you implement these features, you decide to make sure the store works appropriately. You create the databases, seed them, spin up the server, and access the website on your machine to try ordering a few cakes. During this process, suppose you find a bug. You notice, for example, that you can have only one unit of an item in your cart at a time.

For Louis, it would be disastrous if the website went live with such a defect. Everyone knows that it’s impossible to eat a single macaroon at a time, and therefore, no macaroons—one of Louis’s specialties—would sell. To avoid that happening again, you decide that adding multiple units of an item is a use case that always needs to be tested.

You could decide to manually inspect every release, like old assembly lines used to do. But that’s an unscalable approach. It takes too long, and, as in any manual process, it’s also easy to make mistakes. To solve this problem, you must replace yourself, the customer, with code.

Let’s think about how a user tells your program to add something to the cart. This exercise is useful to identify which parts of the action flow need to be replaced by automated tests.

Users interact with your application through a website, which sends an HTTP request to the backend. This request informs the addToCart function which item and how many units they want to add to their cart. The customer’s cart is identified by looking at the sender’s session. Once the items were added to the cart, the website updates according to the server’s response. This process is shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 An order’s action flow

NOTE The f(x) notation is simply the icon I’ve chosen to represent functions throughout this book’s diagrams. It doesn’t necessarily indicate what the function’s parameters are.

Let’s replace the customer with a piece of software that can call the addToCartFunction. Now, you don’t depend on someone to manually add items to a cart and look at the response. Instead, you have a piece of code that does the verification for you. That’s an automated test.

Automated test Automated tests are programs that automate the task of testing your software. They interface with your application to perform actions and compare the actual result with the expected output you have previously defined.

Your testing code creates a cart and tells addToCart to add items to it. Once it gets a response, it checks whether the requested items are there, as shown in figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 The action flow for testing addToCart

Within your test, you can simulate the exact scenario in which users would be able to add only a single macaroon to their cart:

By making your test reproduce the steps that would cause the bug to happen, you can prove that this specific bug doesn’t happen anymore.

The next test we will write is to guarantee that it’s possible to add multiple macaroons to the cart. This test creates its own instance of a cart and uses the addToCart function to try adding two macaroons to it. After calling the addToCart function, your test checks the contents of the cart. If the cart’s contents match your expectations, it tells you that everything worked properly. We’re now sure it’s possible to add two macaroons to the cart, as shown in figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 The action flow for a test that checks whether you can add multiple macaroons to a cart

Now that customers can have as many macaroons as they want—as it should be—let’s say you try to simulate a purchase your customer would make: 10,000 macaroons. Surprisingly, the order goes through, but Uncle Louis doesn’t have that many macaroons in stock. As his bakery is still a small business, he also can’t fulfill humongous orders like this on such short notice. To make sure that Louis can deliver flawless desserts to everyone on time, he asks you to make sure that customers can order only what’s in stock.

To identify which parts of the action flow need to be replaced by automated tests, let’s define what should happen when customers add items to their carts and adapt our application correspondingly.

When customers click the “Add to Cart” button on the website, as shown in figure 1.4, the client should send an HTTP request to the server telling it to add 10,000 macaroons to the cart. Before adding them to the cart, the server must consult a database to check if there are enough in stock. If the amount in stock is smaller or equal to the quantity requested, the macaroons will be added to the cart, and the server will send a response to the client, which updates accordingly.

NOTE You should use a separate testing database for your tests. Do not pollute your production database with testing data.

Tests will add and manipulate all kinds of data, which can lead to data being lost or to the database being in an inconsistent state.

Using a separate database also makes it easier to determine a bug’s root cause. Because you are fully in control of the test database’s state, customers’ actions won’t interfere with your tests’ results.

Figure 1.4 The desired action flow for adding only available items to a cart

This bug is even more critical, so you need to be twice as careful. To be more confident about your test, you can write it before actually fixing the bug, so that you can see if it fails as it should.

The only useful kind of test is a test that will fail when your application doesn’t work.

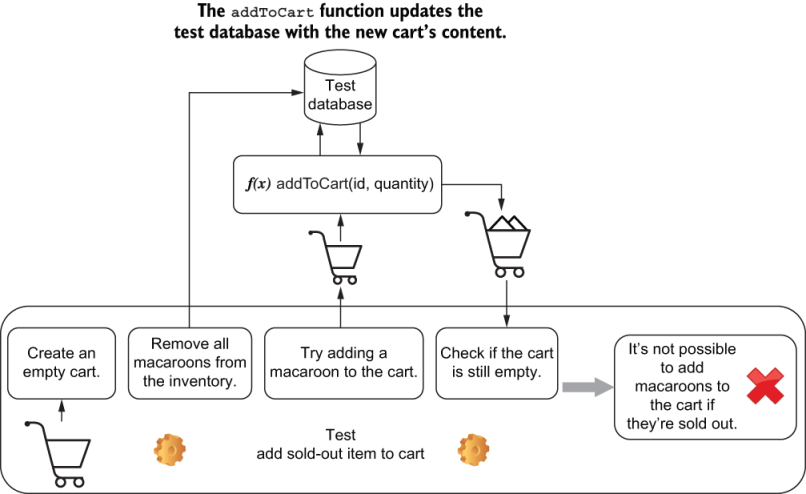

This test is just like the one from earlier: it replaces the user with a piece of software and simulates its actions. The difference is that, in this case, you need to add one extra step to remove all macaroons from the inventory. The test must set up the scenario and simulate the actions that would cause the bug to happen; see figure 1.5.

Once the test is in place, it’s also much quicker to fix the bug. Every time you make a change, your test will tell you whether the bug is gone. You don’t need to manually log in to the database, remove all macaroons, open the website, and try to add them to your cart. The test can do it for you much quicker.

Because you have also written a test to check whether customers can add multiple items to the cart, if your fix causes the other bug to reappear, that test will warn you. Tests provide quick feedback and make you more confident that your software works.

Figure 1.5 The necessary steps for a test to check whether we can add sold-out items to the cart

I must warn you, however, that automated tests are not the panacea for producing software that works. Tests can’t prove your software works; they can only prove it doesn’t. If adding 10,001 macaroons to the cart still caused their availability to be ignored, you wouldn’t know unless you tested this specific input.

Tests are like experiments. You encode our expectations about how the software works into your tests, and because they passed in the past, you choose to believe your application will behave the same way in the future, even though that’s not always true. The more tests you have, and the closer these tests resemble what real users do, the more guarantees they give you.

Automated tests also don’t eliminate the need for manual testing. Verifying your work as end users would do and investing time into exploratory testing are still indispensable. Because this book is targeted at software developers instead of QA analysts, in the context of this chapter, I’ll refer to the unnecessary manual testing process often done during development just as manual testing.

1.2 Why automated tests matter

Tests matter because they give you quick and fail-proof feedback. In this chapter, we’ll look in detail at how swift and precise feedback improves the software development process by making the development workflow more uniform and predictable, making it easy to reproduce issues and document tests cases, easing the collaboration among different developers or teams, and shortening the time it takes to deliver high-quality software.

1.2.1 Predictability

Having a predictable development process means preventing the introduction of unexpected behavior during the implementation of a feature or the fixing of a bug. Reducing the number of surprises during development also makes tasks easier to estimate and causes developers to revisit their work less often.

Manually ensuring that your entire software works as you expect is a time-consuming and error-prone process. Tests improve this process because they decrease the time it takes to get feedback on the code you write and, therefore, make it quicker to fix mistakes. The smaller the distance between the act of writing code and receiving feedback, the more predictable development becomes.

To illustrate how tests can make development more predictable, let’s imagine that Louis has asked you for a new feature. He wants customers to be able to track the status of their orders. This feature would help him spend more time baking and less time answering the phone to reassure customers that their order will be on time. Louis is passionate about cheesecakes, not phone calls.

If you were to implement the tracking feature without automated tests, you’d have to run through the entire shopping process manually to see if it works, as shown in figure 1.6. Every time you need to test it again, besides restarting the server, you also need to clear your databases to make sure they are in a consistent state, open your browser, add items to the cart, schedule a delivery, go through checkout, and only then you’d finally test tracking your order.

Figure 1.6 The steps to test tracking an order

Before you can even manually test this feature, it needs to be accessible on the website. You need to write its interface and a good chunk of the backend the client talks to.

Not having automated tests will cause you to write too much code before checking whether the feature works. If you have to go through a long and tedious process every time you make changes, you will write bigger chunks of code at a time. Because it takes so long to get feedback when you write bigger chunks of code, by the time you do receive it, it might be too late. You have written too much code before testing, and now there are more places for bugs to hide. Where, among the thousand new lines of code, is the bug you’ve just seen?

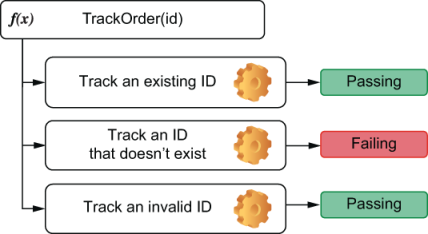

Figure 1.7 The tests for the trackOrder function can call that function directly, so you don’t have to touch other parts of the application.

With an automated test like the ones in figure 1.7, you can write less code before getting feedback. When your automated tests can call the trackOrder function directly, you can avoid touching unnecessary parts of your application before you’re sure that trackOrder works.

When a test fails after you’ve written only 10 lines of code, you have only 10 lines of code to worry about. Even if the bug is not within those 10 lines, it becomes way easier to detect which one of them provoked misbehavior somewhere else.

The situation can get even worse if you break other parts of your application. If you introduce bugs into the checkout procedure, you need to check how your changes affected it. The more changes you’ve made, the harder it becomes to find where the problem is.

When you have automated tests like the ones in figure 1.8, they can alert you as soon as something breaks so that you can correct course more easily. If you run tests frequently, you will get precise feedback on what part of your application is broken as soon as you break it. Remember that the less time it takes to get feedback once you’ve written code, the more predictable your development process will be.

Figure 1.8 Automated tests can check parts of your code individually and give you precise feedback on what’s broken as soon as you break it.

Often I see developers having to throw work away because they’ve done too many changes at once. When those changes caused so many parts of the application to break, they didn’t know where to start. It was easier to start from scratch than to fix the mess they had already created. How many times have you done that?

1.2.2 Reproducibility

The more steps a particular task has, the more likely a human is to make mistakes following them. Automated tests make it easier and quicker to reproduce bugs and ensure they aren’t present anymore.

For a customer to track the status of an order, they will have to go through multiple steps. They’d have to add items to their cart, pick a delivery date, and go through the checkout process. To test your application and ensure that it will work for customers, you must do the same. This process is reasonably long and error-prone, and you could approach each step in many different ways. With automated tests, we can ensure that these steps are followed to the letter.

Let’s assume that you find bugs when you test your application, like being able to check out with an empty cart or with an invalid credit card. For you to find those bugs, you had to go through a series of steps manually.

To avoid those bugs happening again, you must reproduce the exact same steps that cause each one of them. If the list of test cases grows too long or if there are too many steps, the room for human mistakes gets bigger. Unless you have a checklist that you follow to the letter every single time, bugs will slip in (see figure 1.9).

Ordering a cake is something you will certainly remember to check, but what about ordering –1 cakes, or even NaN cakes? People forget and make mistakes, and, therefore, software breaks. Humans should do things that humans are good at, and performing repetitive tasks is not one of them.

Figure 1.9 The steps that must be followed when testing each feature

Even if you decide to maintain a checklist for those test cases, you will have the overhead of keeping that documentation always up-to-date. If you ever forget to update it and something not described in a test case happens, who’s wrong—the application or the documentation?

Automated tests do the exact same actions every time you execute them. When a machine is running tests, it neither forgets any steps nor makes mistakes.

1.2.3 Collaboration

Everyone who tastes Louis’s banoffee pies knows he’s one Great British Bake Off away from stardom. If you do everything right on the software side, maybe one day he’ll open bakeries everywhere from San Franciso to Saint Petersburg. In that scenario, a single developer just won’t cut it.

If you hire other developers to work with you, all of a sudden, you start having new and different concerns. If you’re implementing a new discount system, and Alice is implementing a way to generate coupons, what do you do if your changes to the checkout procedure make it impossible for customers also to apply coupons to their orders? In other words, how can you ensure that your work is not going to interfere with hers and vice versa?

If Alice merges her feature into the codebase first, you have to ask her how you’re supposed to test her work to ensure yours didn’t break it. Merging your work will consume your time and Alice’s.

The effort you and Alice spent manually testing your changes will have to be repeated when integrating your work with hers. On top of that, there will be additional effort to test the integration between both changes, as illustrated by figure 1.10.

Figure 1.10 The effort necessary to verify changes in each stage of the development process when doing manual testing

Besides time-consuming, this process is also error-prone. You have to remember all the steps and edge cases to test in both your work and Alice’s. And, even if you do remember, you still need to follow them exactly.

When a programmer adds automated tests for their features, everyone else benefits. If Alice’s work has tests, you don’t need to ask her how to test her changes. When the time comes for you to merge both pieces of work, you can simply run the existing automated tests instead of going through the whole manual testing process again.

Even if your changes build on top of hers, tests will serve as up-to-date documentation to guide further work. Well-written tests are the best documentation a developer can have. Because they need to pass, they will always be up-to-date. If you are going to write technical documentation anyway, why not write a test instead?

If your code integrates with Alice’s, you will also add more automated tests that cover the integration between your work and hers. These new tests will be used by the next developers when implementing correlated features and, therefore, save them time. Writing tests whenever you make changes creates a virtuous collaboration cycle where one developer helps those who will touch that part of the codebase next (see figure 1.11).

This approach reduces communication overhead but does not eliminate the need for communication, which is the foundation stone for every project to succeed. Automated tests remarkably improve the collaboration process, but they become even more effective when paired with other practices, such as code reviews.

Figure 1.11 The effort necessary to verify changes in each stage of the development process when automated tests exist

One of the most challenging tasks in software engineering is to make multiple developers collaborate efficiently, and tests are one of the most useful tools for that.

1.2.4 Speed

Louis doesn’t care about which language you use and much less about how many tests you have written. Louis wants to sell pastries, cakes, and whatever other sugary marvels he can produce. Louis cares about revenue. If more features make customers happier and generate more revenue, then he wants you to deliver those features as fast as possible. There’s only one caveat: they must work.

For the business, it’s speed and correctness that matters, not tests. In all the previous sections, we talked about how tests improved the development process by making it more predictable, reproducible, and collaborative, but, ultimately, those are benefits only because they help us produce better software in less time.

When it takes less time for you to produce code, prove that it doesn’t have specific bugs, and integrate it with everyone else’s work, the business succeeds. When you prevent regressions, the business succeeds. When you make deployments safer, the business succeeds.

Because it takes time to write tests, they do have a cost. But we insist on writing tests because the benefits vastly outweigh the drawbacks.

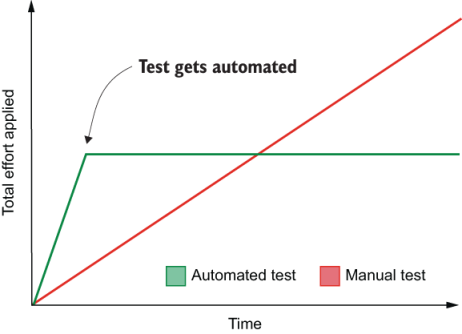

Initially, writing a test can be time-consuming, too, even more than doing a manual test, but the more you run it, the more value you extract from it. If it takes you one minute to do a manual test and you spend five minutes writing one that’s automated, as soon as it runs for the fifth time it will have paid for itself—and trust me, that test is going to run way more than five times.

In contrast to manual testing, which will always take the same amount of time or more, automating a test causes the time and effort it takes to run it to drop to almost zero. As time passes, the total effort involved in manual tests grows much quicker. This difference in effort between writing automated tests and performing manual testing is illustrated in figure 1.12.

Figure 1.12 The effort applied over time when doing manual testing versus automated testing

Writing tests is like buying stocks. You may pay a big price up-front, but you will continue to reap the dividends for a long time. As in finance, the kind of investment you will make—and whether you will make it—depends on when you need the money back. Long-term projects are the ones that benefit the most from tests. The longer the project runs, the more effort is saved, and the more you can invest in new features or other meaningful activities. Short-term projects, like the ones you make in pizza-fueled hackathons, for example, don’t benefit much. They don’t live long enough to justify the effort you will save with testing over time.

The last time Louis asked you if you could deliver features faster if you were not writing so many tests, you didn’t use the financial analogy, though. You told him that this would be like increasing an oven’s temperature for a cake to be ready sooner. The edges get burned, but the middle is still raw.

Summary

-

Automated tests are programs that automate the task of testing your software. These tests will interact with your application and compare its actual output to the expected output. They will pass when the output is correct and provide you with meaningful feedback when it isn’t.

-

Tests that never fail are useless. The goal of having tests is for them to fail when the application misbehaves no longer present.

-

You can’t prove your software works. You can prove only it doesn’t. Tests show that particular bugs are no longer present—not that there are no bugs. An almost infinite number of possible inputs could be given to your application, and it’s not feasible to test all of them. Tests tend to cover bugs you’ve seen before or particular kinds of situations you want to ensure will work.

-

Automated tests reduce the distance between the act of writing code and getting feedback. Therefore, they make your development process more structured and reduce the number of surprises. A predictable development process makes it easier to estimate tasks and allows developers to revisit their work less often.

-

Automated tests always follow the exact same series of steps. They don’t forget or make mistakes. They ensure that test cases are followed thoroughly and make it easier to reproduce bugs.

-

When tests are automated, rework and communication overhead decrease. On their own, developers can immediately verify other people’s work and ensure they haven’t broken other parts of the application.

-

Well-written tests are the best documentation a developer can have. Because tests need to pass, they must always be up-to-date. They demonstrate the usage of an API and help others understand how the codebase works.

-

Businesses don’t care about your tests. Businesses care about making a profit. Ultimately, automated tests are helpful because they drive up profits by helping developers deliver higher-quality software faster.

-

When writing tests, you pay a big price up-front by investing extra time in creating them. However, you get value back in dividends. The more often a test runs, the more time it has saved you. Therefore, the longer the life cycle of a project, the more critical tests become.