9

Enabling Change

The Skills of Dialogic OD

In this chapter I address the kinds of skills and mindset an OD consultant needs if change is viewed as an ongoing, fluid process that emerges from people in organizations evaluating and revising their practices and the stories they have about the purpose of their work and collective objectives. I will offer a practice-based account of how change in an organization can be enabled as part of a series of meetings, training sessions, and coaching based on Dialogic OD thinking. Rather than only theorize, I also recount different aspects of enabling practices as they were experienced by the participants during the consultation.

Positioning the Dialogic Consultant

As discussed throughout this book, a dialogical view of organizational change is a profound leap toward a different mindset from that offered in the dominant change management literature. Lewin’s (1951) unfreeze-move-refreeze dictum, which sees change as episodic, has carved itself into the body of ideas from which the OD and change management literature have developed. Dialogic OD, on the other hand, sees change as constant and ongoing, which results in some very different perspectives. Organizations are not viewed as things, but means to ends that are constantly in a flow of creation and re-creation. The Diagnostic OD Mindset views the ability to predict and control as the aim of good change practice, bringing the organization from one level of stability to another. The Dialogic OD Mindset views the ability to stimulate relationally responsive conversations that channel peoples’ needs and desires toward continuously evolving ends as the aim of good change practice. From this latter point of view, change is always happening; stability and organization at any point of time is a dynamic result of addressing ongoing changes, channeling them toward desired ends.

From this point of view action is always taking place, even when we experience being stuck, since being stuck is a result of continued repetitions of practices that do not respond to the complexity of the situation that people find themselves in. Enabling change from a Dialogic OD Mindset is to engage with people in relationally responsive conversations that enrich language, offer generative images, and enable people to respond to the social reality that emerges from having different conversations with participants holding a diversity of ideas and points of view. So Dialogic OD practitioners do not think of themselves as people who unfreeze and refreeze, but instead as people who convene or host different kinds of conversations. In these conversations the intent is for people to view and review their narratives, practices, and desired ends, and thereby engage in a process of redescribing (Rorty, 1991) the world in which they want to live and how to realize their new desired ends and purposes.

When we talk about enabling change, we want to produce a change in how people act. But what is involved in creating change in people’s organizational lives and actions? In this chapter I offer a practice-based account with quotes from people taking part in a Dialogic OD process. Though this account expresses the experience of people in this particular event, I believe it is applicable more generally, and represents what is needed to enable change in organizational life. The case expresses a variation of Dialogic OD consulting wherein training is an integral part of enabling change. I believe training integrated in a dialogical process can be a powerful way of supporting and sustaining change, since participants get to experiment in training sessions with different ideas and streams of thought. By offering a different vocabulary in which these new changes make sense, training can reinforce novel practices. Dialogic training offers a chance for enabling second-order change, meaning change in the way people relate and make sense of the world and their role in it.

A Short Example of Enabling Change

In a recent project I was invited to facilitate a change in the legal department of a large municipality. Their leader wanted to move away from being exclusively experts on legal matters to being consultants who could engage with and facilitate events to assure that their recommendations and advice would lead to desired outcomes and add to the value created for the organization. She described a series of cases in which they had given qualified and legally sound recommendations, but concluded it did not help the organization as intended. There were also cases in which they found themselves leading meetings under very difficult relational circumstances, with frustration, power asymmetries, and disagreements, and found their professional skills limited, not really knowing how to be effective. They had also received feedback from their client organization that they should become better at addressing organizational context and complexity in their counseling, offering more than pure legal advice.

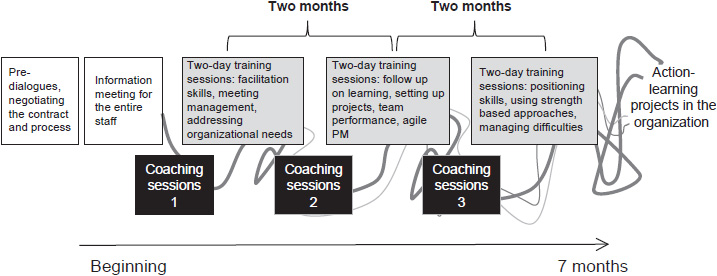

The Dialogic OD process in this case was created after a series of meetings between myself and the sponsor, the leader of the legal department. The year before, I had coached the people in this group on a difficult case, and some of the legal consultants wanted to gain more training in facilitating meetings and consulting to better meet organizational needs. In response, I offered a design that included three different threads of activities woven together through a process stretching over seven months. These were:

1. Three coaching sessions with each consultant, plus the leader, focusing on personal challenges in facilitating and each participant’s individual learning objectives. The learning needs that emerged from these conversations were then used to produce the content for the training sessions, so that the experience of a tailor-made design was created.

2. Three training sessions involving the whole department, each of two days’ duration. The training blended teaching the art of Dialogic OD, practice training based on their own case stories and challenges, and reflections on learning from these experiences. Each two-day session ended with the group producing assignments that they would go back home and start developing.

3. In between training and coaching sessions the group committed to practicing and developing new skills, so that they could learn about the real-life consequences of applying new practices in the organization. As the process evolved, the number of action learning projects grew and their complexity increased. The learning was then used as a way of tying training sessions together in an action learning style of practice, so that the story of change and new experiences was reinforced and legitimated.

Graphically the process is shown in Figure 9.1.

The impact of this design was captured by one of the legal consultants who reported on her experience with the process:1

It has worked out really nice in the way the process has been designed. We have had individual sessions, where I believe that it was possible to get closer to each one of us as individuals—where are we and how are we working; how we are changing our practice. And, what are our needs and what do we worry about? Things have been questioned and then reassembled during the theoretical training sessions, but also through the practice sessions—so in a way it has just been an experience of it being like play in some way or another which has produced a natural approach to it. This is how I feel about it. I don’t feel that I have been on a course where I have thought that I was on the school bench again, just sitting and listening and receiving and then for myself, trying to work out how to apply it at home. It is probably because we have used each other, we have used and practiced it together during the course and not just received it. In a way we have ourselves participated and been active, we have experienced that we have been used in designing the training, that it has been altered as it progressed. It hasn’t been like a box we should fit into, the box is fitted to our purposes and that really worked out well, I believe.

Figure 9.1 The Law Department Case.

The experience of being continuously involved in actively forming and shaping the ongoing creation of the program is an example of responsive, dialogic practice. Her experience of not having to fit into a box, but rather feeling that the program and the specific decision making were related to their purposes, illustrates the point of responsiveness: it ensures purpose and meaning emerges and changes over time. In the beginning, the process centered around learning new skills and practices, but during the first training session it emerged through participants’ conversations that the project had to question the way they were working as a department. This change in purpose meant an immediate change in program, and an alteration of day two. This constant negotiation of meaning, purpose, and content continued throughout the process. As they applied their newly developed ideas in their legal practice, the participants created new experiences and learning. As a participant reports, the process created a whole new practical reflexivity:

We started to relate to the question of who we wanted to be. Before we were much more law, but now we consider who we want to become and how we want to be perceived, how we enter a room and not least what kind of options we have for choosing. It can certainly be that we want to be perceived in one way in this situation and in another way in a different situation, so we have become much more conscious in relation to why we do it and how we want to be seen by others in the situation.

Required Skills for Enabling Dialogic Change

In order to create a coherent process the consultant must be able to perform different sets of skills. Possessing skills for dialogue, such as creating rapport, asking open-ended questions, hypothesizing, listening, and imagining how the world might look from within others’ lived circumstances, and therefore being able to engage with people in ways that produce the kind of conversations that elicit change, are important. But dialogue skills are not everything. There are several other skills that need to be mastered in Dialogic OD. Barnett Pearce (Pearce and Pearce, 2000) presents three sets of skills that Dialogic OD practitioners need to master. These are Strategic Process Design, Event Design, and Dialogic Facilitation Skills.

Strategic Process Design

The strategic process design is a plan for a coherent narrative of change displaying a deliberately chosen sequence of conversations that respond to needs and requirements of the organization and lead to a desired outcome, as it can be articulated in the early initiating conversations. The strategic process may last from a few weeks to several years, and the design will certainly change during the process as people learn and apply new knowledge in practice. (Pearce and Pearce 2000, p. 415)

In our case, we see a strategic process design wherein a series of activities are coordinated in space and time that provide a coherent and seemingly orderly narrative. Providing a coherent narrative is quite important, since it helps to manage the anxiety often experienced during the process of accepting the change proposal. Offering coherent narratives directly addresses the importance of providing organizational legitimacy for engaging in interactive processes. A strategic process design meets that need if the consultant provides a convincing storyline or rationale. Essentially this is the work of architecting a change process with a clear beginning, middle, and end and describing it in a way that makes sense to people. Many Dialogic OD methods offer these sorts of architectures (steps in the change process), and more experienced consultants will innovate in and around them. In larger systems this is often done with the help of a design team, as described in Chapter 10. When done well, this leads to people experiencing a sense of certainty, or at least hope, that the process and change they are engaging themselves and their organization in will likely result in the desired outcomes. Yet, as the quote from the participant highlights, in a well-run Dialogic OD process the experience will feel much more responsive and emergent than the initial narrative might suggest.

I have not come across a single approach for how to create these designs, and from my experience of supervising numerous consultants I see that people apply many different approaches. Inquiring into my own practice I find three consistent practices:

1. As a first draft I start drawing the different conversational flows that appear to be central to the assignment. At first this looks like a messy sketch, but when elaborated the second drawing often appears clearer, with a sense of coherence. Once coherence emerges it is helpful to look for aesthetic ways of presenting the design and the flow of it. The art of graphic facilitation offers some simple but very applicable techniques that can easily be learned.2

2. I imagine what kinds of conversations are needed in order to achieve the desired outcome and how these conversations might take place. Drawing on knowledge of how organizations operate, how decisions are made, who is involved in the different conversations, and so on, is an important source when making sense of a process design. It is often the case that a design is not fully complete, and I often have a good sense of where missing links will occur. In practice what emerges during a process will provide the necessary links.

3. It is important to stay in dialogue with the clients, and I often call them during the design process. First drafts are often produced in a meeting with the client in a brainstorm-like dialogue, which is then further elaborated after the meeting. In a recent project I had to present a draft for a big project lasting three years. Here I brought two different design proposals to the meeting that expressed two different ways of working dialogically with change.

There can be no one right strategic process design, since what works in one organization has no chance of success in another. Good designs provide “good enough” coherence and offer a narrative that makes it believable that the process will lead to desired outcomes. It is possible to rely on the authority offered by recognized change methods, such as Appreciative Inquiry, Open Space, Future Search, and so on. While this can be tempting and assuring (both for the consultant and client), a consultant may run the risk of making the purpose of the client fit the method rather than the other way around.

A good design needs good consulting if it is to produce a positive difference in people’s lives. In order to create such experiences of positive difference two other skill sets are important.

Event Design

Events are sequences of activities that occur within a single meeting; they may last from less than an hour to several days. Many types of events, deliberately sequenced, may occur within a [dialogic] strategic design. (Pearce and Pearce, 2000, p. 416)

As we saw in the case described above, the different activities informed a fine tuning of the design by integrating the participant responses into the unfolding content and process of the training. A skilled consultant holds a repertoire of actions to draw upon, which means that the consultant can offer unique responses to the needs and requirements of the organization, instead of responding only according to a few methods or step-by-step planning. This allows the consultant to keep the process and the choice of content open, so that what gets included is as responsive as possible to relational engagement and emerging meanings. In the legal department case, while the strategic process design remained constant as a kind of scaffold, each session was uniquely shaped and formed by ongoing responsive dialogues within the group of participants in their work context, as well as through the relationships between the consultant and the sponsor, each group member, and the group as a whole. Later the many different aspects of an emerging dialogic process will be presented in much greater detail.

Many of the Dialogic OD approaches in Table 1.2 could be considered event design methodologies. In addition to the well-known ones like Open Space, World Café, and Work Out, there are others less used by OD consultants but good to know such as charettes, moments of impact, and intergroup dialogue. The more experienced the consultant, the less likely they are to use any of these methods in “pure” form, instead mixing and matching methods to produce a design more likely to be effective in the specific context. But even more important is the mindset behind any design. The Diagnostic OD approach prefers analysis and planning to achieve desired outcomes, while the Dialogic OD approach advocates a more responsive, evolving, and engaged involvement. While Diagnostic OD consultants see themselves as separate from the client, offering advice from the outside in, Dialogic OD consultants see themselves as immersed in and part of the process, offering advice from the inside out. Diagnostic OD prefers to have a clear agenda and explicit content, which can then be implemented and subsequently evaluated according to anticipated learning outcomes. The Dialogic OD approach is less certain, less clear, and much more responsive, evolving, and emergent. The Dialogic/Diagnostic difference can be expressed as “artistic” versus “instrumental,” the ability to respond fluently and coherently without big designs versus having a clear agenda and a step-by-step approach to events. These are not necessarily either/or choices. Any change effort holds a uniquely artistic dimension and an instrumental dimension. How to best balance these will be different in each situation. Being very instrumental, however, does not seem to work well in dealing with complex situations, adaptive challenges, or wicked problems. While the dialogic approach often seems more difficult to explain, it also seems more likely to succeed (Weick and Quinn, 1999), since it involves people directly and works to produce meaningful changes responsive to the local context of people in their work.

The more the individual event responds to the emerging meanings and needs of people, the more likely they will fully commit to engaging in learning. In this case it was built into the program by having the coaching sessions inform the content of the training sessions and by not planning day two of each training session before the end of day one. During events a consultant needs to respond continuously, very much like a jazz improviser (Barrett, 1998, 2012), who goes with the flow of the music yet is ready to take chances in the firm belief that the meaning of the music, the groove, reemerges as other people join in to advance the music. Obviously this requires training and consulting experience for the consultant, the same as for the musician, and less experienced consultants might therefore be inclined to seek a platform of certainty by sticking to a script. But sticking to a script also means dealing with the paradox of trying to preplan what ultimately depends on a complex, responsive set of human interactions that leads to emergent meanings and outcomes. In order to address this paradoxical position the Dialogic OD consultant must demonstrate skills in action while “onstage.” The skills to stay in the moment with others, to engage their concerns and meaning making without providing answers or false certainty to assuage their anxiety about change, and to facilitate conversations that generate new possibilities are vital, and especially so to enable immediate and future actions. What some of these skills are and how they are manifested is discussed next.

Dialogic Facilitation Skills

The success of any event depends in part on the ways that facilitators act or respond, in the moment, to what the participants do. One level of facilitation skills includes conventional practices such as timekeeping, providing supplies, recording conversations, and ensuring that all participants have sufficient “air time.” A second level of facilitation skills consists of (re)framing comments by using circular, reflexive, and dialogic interviewing procedures; positioning participants as reflecting teams and outsider witnesses; and coaching participants in dialogic communication skills. (Pearce and Pearce, 2000, p. 417)

While the skills described in the first set of the quote are quite basic, those of the second kind are more complex and require a different level of understanding and practice. Some of the Dialogic OD methods listed in Table 1.2 can be thought of as facilitation skills: art of convening, dynamic facilitation, narrative mediation, and organizational learning conversations, to name a few. This second set of skills can be thought of as having two dimensions. One is a set of responsive capabilities going outward, like asking questions to keep the flow of the conversation going. The skills in the other set are based more on the inward experience of the consultant, such as awareness of one’s experience in the moment. Pearce and Pearce (2000) describe a few essential outward practices. I will describe three:

Reframing. This is the ability to rearticulate the intentions behind what people express in a way that supports the unfolding process. If a person utters a blocking statement, a positive reframing response would highlight the positive intention motivating the negative judgment. When judgments like these offer no solutions or proposals for action, they block productive conversations, especially if others then want to debate whether the judgment is correct or warranted. For example, a person might say, “I think we are stuck and getting nowhere with this conversation!” Then the consultant might respond by saying, “Thanks for drawing our attention toward a need to remind ourselves where we need to go, and that moving forward is important in order to keep motivation high!” This could be followed by a question reinforcing the reframing: “What would be a wise move now in order to reestablish focus on our desired outcome so that we produce an experience of movement again?” By reframing comments, the consultant demonstrates valuing whatever gets articulated by a participant as important. This has at least two important effects. It keeps an inclusive, nonjudgmental conversation going, so that no one experiences being either right or wrong. It also encourages generativity by suggesting a different way of thinking about an issue or dynamic without telling the person what to do.

Circular questions. A circular question draws attention to how everything is in relationship to something else. For example, participants could express some difficulty in imagining how they could act differently. One of the lawyers from my case questioned how they could change the way they related to clients in the organization. I then asked: “If we asked the client how they could see you act in a consultative fashion, what would they say?” and “If we imagined that we managed to find a good way forward, what would you hope that your client would experience from your changed practice?” What makes these questions circular is the relational dimension they elicit. People are asked to view themselves from the outside, which takes people from thinking “I can’t do this!” into imagining “how others might experience me performing differently.” There is a profound difference between asking a question about what people think of themselves and asking people what they imagine other people might say about them. Circular questions make people simultaneously subject and object, which provides a difference in thinking that is more likely to stimulate creativity and new courses of action.

Reflecting teams. Another outward practice is setting up and facilitating reflecting teams that provide a type of sounding board to help focus on moving forward and enabling action. When people listen to the difficulties expressed by a person, they develop ideas about ways of relating to that situation. Rather than just pouring advice onto the person expressing concerns or difficulties, reflecting team members are instructed to listen to the person describe the issue, and then to speak only to each other about the dilemma, not directly to the person. In that way the focal person is positioned as a listener without having to respond to each utterance. This encourages more listening and less defensiveness. This also allows the focal person to select between the different ideas in a way that makes sense for the person. In this way stronger ownership of the ideas gets created, and when the person is asked to comment on what made sense and how things might proceed, one will often find that the person has changed position in relation to the original difficulty.

Inward Skills

Another set of skills that a consultant needs relates to managing and attending to one’s inner responses to what is happening to them and in front of them. A consultant experiences a whole set of bodily responses and sensations; for example, feelings of joy, fear, sadness, happiness; changes in pulse, sweat, dryness, a variety of wishes, wants, and motivations, and a range of inner dialogues. The skills required to attend to these dimensions of the consulting process require a professional willingness to understand that we are not apart from our engagements, but instead are part of the process and therefore subject to reactions and responses to the emerging situation. Effective Dialogic OD consultants need the self-awareness and self-reflexive skills to know how our bodies react and respond to different situations, to understand the motivations and desires that animate our actions, and how our inner dialogues may distort or enable our abilities to be fully engaged in what is happening in front of us. If we are not aware of the possible meanings flowing from our spontaneous responsive engagement we risk being carried away by our own meanings, missing what is happening to others and the meanings they are making.

Solsø (2012, pp. 24–25) offers a rare insight into the language that one might start developing about this inner aspect of consulting. She reports from an episode where she is ending a day of consulting with a group. The leader (Carl) offers some final comments and she reports what happens next:

As Carl says this I look around at the group. I notice that some of them nod. Most of them look like it makes good sense to move into a final stage. Though there is something that disturbs me. I sense kind of dissonance—something which isn’t quite so clear. Maybe it is an expression of us being at the end of the day and people are getting tired. Maybe it is an expression of something else. One of the employees, Elise, looks at Carl and says: “Eehh…. I really don’t know. What is it exactly you want us to do?”

Carl looks at me and I sense that it is me who has to move the group forward now. I just have some doubts … I am reminded of some theoretical aspect of my training which is arguing for the importance of being clear and transparent about the intentions of the consultant in relation to certain choices made during a process and I decide to lay open to view my intentions for this final stage of the process.

Some comments are made by the leader and then another employee expresses some doubts and uncertainties. Solsø continues her reflection:

Kirsten’s [the employee] comment speaks directly into my doubts. I can feel how her words make good sense to me even though it complicates the process and makes it difficult to finalize in time. I sense the pressure raise on me as I have to find a proper response to how to move on. I look at the group. Several of them nod as if they agree with Kirsten. I think that it was good that Kirsten had the courage to express herself. The question though is what do we do now …?

One central skill demonstrated in this brief reflection is the ability to admit to one’s own ambiguity and uncertainty, turning it into a productive aspect of making decisions on the spot. The case illustrates that her bodily sensations emerge even before what they point toward gets clearly articulated by a participant. She notices her worries but does not act immediately; rather they prepare her by initiating an inner dialogue, expanding her responsive repertoire and enabling several courses of possible actions. Skilled consultants hold what Stacey describes in Chapter 7 as sound practical judgment that enables them to be relationally responsive to the needs of people engaged in the processes being facilitated.

Such inner skills are not learned in a weekend course. They usually require a good amount of time spent in body-oriented training and often require a relationship with a skilled mentor or a professional, such as a coach with specialized skills in somatic reflexivity (I have trained with a professional actor and coach) or a somatic psychotherapist.

Enabling Conditions: Learnings from Practice

So far this chapter has provided a mainly theoretical discussion of enabling change in Dialogic OD. Now we shift to the practice of consulting based on a specific case example. With enough practice and experience confidence grows, and mastery is gained. At this point methods and techniques no longer stand in the foreground of one’s practice; rather, one starts to engage in relationally responsive ways to the unique details of an episode. This means moving from studiously trying to connect dialogically with the other participants into being fully within, and spontaneously part of, a dialogically structured conversation. Shotter (1993) calls this kind of dialogical, responsive practice “knowing of a third kind.” It is very similar to the difference between following a map and being able to read the territory, the wind, the sun, and so on while using the map for orientation purposes alone.

A series of learning dimensions of what enabled action and change will be presented from the case. For each example a brief intro is given followed by a quote from a participant and then additional commentary. While these are taken from a single case they can be generalized to most situations.

The Collaborative Relationship between Participant and Consultant

We were given an ownership over the process and we were given the opportunity to contribute with what we thought needed adjustment during the process.

As elaborated in Chapter 8 on collaborative co-inquiry, a Dialogic OD consultant is in a partnership with the client; the client is not on one side and the consultant on the other. The process of engagement is a mutual learning experience. The consultant needs to learn about the participants; who they are, how you can work with them, to understand their challenges, and for the participants it is the other way around. The consultant needs to learn about the meaning of the project, especially how meaning changes as things start to progress. The consultant needs to be constantly mindful of the learning that is happening in and around the group and the individuals. One way of doing this is to really allow oneself to understand what change looks like from within their context, what might be challenges and what might be opportunities not yet articulated. People are more likely to trust if they feel that one has an understanding of how life looks like for them.

Ensure that participants have meaningful opportunities to coconstruct the process and take important decisions. This can be done by asking them questions, inquiring into what processes and changes make sense to them and how what makes sense can be amplified further. Being transparent about dilemmas, about one’s thoughts on how to make good choices, and then acting responsively to their ideas is a way of empowering the voice and perspective of the participants. In this quote one of the participants reflects on the relationship between consultant and participants:

The consultant really tried to live his way and understand our world. What kind of complexity we are part of and what is our role in the organization. Understand our professional background, our education and from this propose a goal for the process of resolving a legal matter by means of non-legal practices. I think it really worked out well that the consultant understood the world from which we are coming and on the back of this adjusted the process to our group. It was an experience of being taken seriously. I think it is important to balance between taking the participant’s needs and perspectives seriously and at the same time maintaining his professional integrity and willingness to go against participant wishes if they appear incoherent to the consultant, also if this means creating some level of resistance.

And another participant continues:

I could feel for myself what it means if you are co-deciding and co-contributing and being involved and active. In this way the process has worked on several levels, while I was there it has worked in such a way that I have embodied and sensed what it means to have your voice heard etc. And then coming home between modules I have used this experience in guiding me to do the same to other people in my work.

In the first quote the participant expresses her experience of the engaged involvement of the consultant. She notes that the consultant sees inside the world of the participants, understands the complexity as they see it. Further, the consultant expresses this knowledge by proposing a change goal in a playful way, saying that they should be able to solve a legal matter in a nonlegal way. Also the participant states that it was important for her experience of the consultant’s expertise that he stuck to his own professional judgment even though in some cases that meant disagreeing with the participants. It is a misguided conception of dialogue for a consultant to hold on to the belief that it is wrong to offer expert suggestions as part of dialogic consulting. Rather, if qualified, such perspectives can be highly productive if participants experience a transparency about the thinking behind one’s statements. This position, though, is debated among consultants.

From the second quote we get a clear expression of how people feel when they are fully part of a dialogical relationship with a consultant. From such relationships a whole array of possibilities arises because people usually start to express confidence in the relationally responsive arena that is emerging. It is as if people trust that their point of view and opinions will be taken seriously, and therefore their need to be in control diminishes, which further allows change to flow freely from within engaged dialogues. This change is expressed as trust in changing her behavior at home in the organization, and as such is a brilliant example of the power of Dialogic OD.

Scene-Setting Activities

I believe that it is important that we had these intensive meeting sessions. If we had met every Thursday for two hours in the morning at the city hall then it wouldn’t have worked as it did.

When preparing an event it is important to think of scene-setting activities. These can be very different from project to project and cover the different considerations one can make in relation to crafting a coherent narrative for the process. A first consideration is to imagine what kind of conversations the participants, including the Dialogic OD consultant, need to pursue in order to achieve the desired outcomes. Then one needs to consider where these conversations can take place and how much time is needed. Are there any special requirements? How would I like the room arranged? The requirement is basically to be mindful that everything matters; how one orchestrates conversations may support or hinder what one hopes to achieve.

As basic as these thoughts may be, all too often people are not paying any particular attention to them. For example, think of a university as a scene for learning—are things optimal? As a consultant I have worked at hundreds of locations, in countries as different as China, Greenland, the United States, and the Scandinavian countries. The differences in how a culture expresses its practical as well as aesthetic preferences are enormous. If you consider how much money is spent on bringing people together in organizations for special events or training, it is a dimension of OD consulting that needs constant attention. It will be a poor start to arrive for a big organization meeting, with people who have traveled long distances, and then realize that no one has arranged breakfast, the audiovisual equipment is not working, the tables and chairs in the room are in a mess, or the room is too small and there is no space to move around. For the people attending, making sure that such simple things work well is on the shoulders of the consultant even though the client organization may have promised to arrange them.

In our case example I needed good premises for group sessions, which included a room large enough to hold the group. I knew that I wanted them to work in many different dialogic constellations, so I preferred round tables, with white tablecloths and large sheets of paper so that they could write on the table yet keep it elegant with a clean look. Audiovisual facilities should be in place and the exterior of the room should be welcoming and stimulate conversations. There also needed to be a coffee station, armchairs, high tables, and chairs. I had been assured that there were plenty of flip charts, pens, Post-Its, and the like for creative activities. A good breakfast with fresh homemade bread and cappuccinos and a nice buffet for lunch were also provided. Breakfast was not extravagant, but it supported an implicit story and experience that everything was arranged with detail in mind. The best response one can get is a relaxed group that feels assured that the silent scene-setting circumstances are just right and they are ready to fully engage.

For the participants in this case being away from the office was also important. One reported: “Having a very busy workday, it was important that the intensive sessions were away from the office. Also having two intensive days, with time taken out, booked in the calendar took us away from our daily obligations away from our normal setting really made it intensive.”

Shifting the scene by being away from the office was important to produce a different space for learning. For this group the experience of intensity was important, since it fitted particularly with their stories of themselves as being very hard working, disciplined, and effective. Further, the scene needed to reflect their self-image; it would have become an issue and an example of poor judgment on my side if it had not fitted, which then would have played negatively into the conversations and the training.

Focus on Success

When you are engaged with your everyday doing, then you can easily drown—we easily forget how much we are actually doing. So it really becomes important to stop and start a conversation—both in order to celebrate the successes, but also to pass on your knowledge to one another.

In many different situations it is often an impactful move to inquire into the successes of people’s practice (Cooperrider and Srivastva, 1987), especially if these inquiries focus on the details involved—for example, what people did, where it happened, or how it happened. Engaging in such conversations leads to at least two direct spinoffs. One is the appreciation and spreading of knowledge that comes from direct involvement. This also leads to reinforcement of these practices, since people are likely to continue to do what gets appreciated and valued by others in the organization. The second spinoff is the exploration of unintended but successful learning outcomes—that is, a positive deviance (Pascale and Sternin, 2005). Often something happens during a process that simply stands out as excellent, something that could not have been planned. The power of positive deviance examples can be extraordinary and they hold an educational potency for the whole change process. A common response from the group sounds like, “if this can happen, then anything is possible!”

In the legal department case, our point of departure was acquiring new tools for facilitation. Two experiences became hallmarks of the process. The first concerned one of the legal consultants who was the most reluctant to change. From the beginning she had made clear that she had difficulties seeing the purpose and relevance of the project. But shortly after the first module she took a 180-degree turn, showing remarkable talent for working in these new and desired ways and becoming a reference point for the others in the group. A second experience was the effect that the training had on the whole group. They revised their work patterns and sought collaboration rather than working in solitude as was the prior case. This influenced the context of the process, since it was no longer simply a training program but an organizational change project.

In another example, a participant reports on one of the reflection exercises where participants had to draw all that was happening that was successful and then reflect on what brought most value to the organization and to their practice: “It was really made visible how much we had already moved and changed our practice and it really connected with celebrating the successes. It is really about focusing on all the things that we are pursuing which are new and that we gain so many experiences that we can take with us that are really, really positive. I also think that it does something to all of us making visible all that has been going on over the past month.”

What appears ordinary in moment-to-moment activity in the organization can retrospectively become an extraordinary experience and a story that holds the power to lead by example. Making these visible to the whole group can reinforce change in actions, and help move them forward.

Focus on Creating a Sense of Inclusion

It’s the feeling that we are together in doing this, we share it. It only works because everybody plays along.

The change process in OD is mainly about learning, and it is often taken as implicit that it is individuals who learn and not the group as a group. But extensive research highlights that individuals learn in relation to the people they engage with and it is important to recognize the group as a community of practice that learns as a group, and because they are a group (Wenger, 1998). Indeed, from the early research in social psychology (Lewin, 1951) we know that people are more inclined to enable a change in behavior if they feel commitment and loyalty to a group of people that can hold them accountable for carrying out new actions. Central to this work is a deliberate attempt at creating a shared purpose for the process and a sense of inclusion and belonging. One of the participants from our case example reports on her experience:

It creates a kind of willingness, you really want this to succeed and if you share this feeling with the people whom you have to work with then it really makes things move on. If we do it together it brings something forward that wouldn’t be possible through traditional approaches. I don’t know if willingness is the right word, but it’s a kind of fighter spirit, we are together in wanting it and everybody takes ownership. Certainly it offers a good space to work in. Times fly and things run. People are more willing to engage and then you move faster towards something useful because everybody works positively toward a shared objective.

Research into team performance underlines that the power of collective performance supersedes individual performance (Losada and Heaphy, 2004; Rath and Conchie, 2008), and indeed team performance is the only unit of measure correlating with organizational performance (Harter, Schmidt, and Hayes, 2002). This goes for specific tasks as well as for learning. But in order for a community to succeed it needs particular attention and full integration in the consulting process. The consultant’s Dialogic OD skills are critical, since learning in teams draws on the power of collaboration and dialogical conversational practices that lead to the emergence of new narratives about identities and possibilities along with their associated emotions and expectations.

Learning as Play

The tools that I have now are very close to those that I thought I needed but I have learned them by playing or in some other way that I hadn’t thought of before.

From our childhood our ability to play is closely linked with learning (Bateson, 1972). When playing, one holds open the process of learning on two levels. On the immediate level is the activity itself; when we play we hold open an improvisational space, since we can allow ourselves to experiment with our role, our practice, our identity and we can invent as we move along. On another level playing operates as a way of bridging contexts, the context of the known and that of the emerging. We can allow for greater freedom when playing than at work, where roles are much more fixed by routines, rules, and agendas. The advantage of playing is that when one experiences something new that works out well, one simultaneously holds open the opportunity to rework one’s original context and therefore one can more easily change practice when reentering the work context. It is always worth creating a light atmosphere of joy, laughter, and playfulness, since it stimulates a willingness to try new actions and test new forms of practice. Furthermore, nothing is more convincing than one’s own experience of succeeding, as a participant from our case says:

The experience in your own body that this really does work and makes sense makes you want to do it again in other situations, not because I have to, but because I want to. Now I play with different approaches, I might try one tool and if I feel that something else is needed I try out something different as long as it makes sense.

When one is engaged in playing, rationality is not the foremost criterion for what is right to do; the criterion is the embodied experience that goes with trying something different and succeeding. If the participants are successful, the context of play can be extended into the everyday work world so that they actively engage with challenges in more playful ways and are less concerned with being right and wrong.

Safe-Unsafe Conditions

It was my experience that in the beginning one is not certain whether this was about our professional skills or whether this was about our personalities, it really came close in the beginning. We felt uncertain because this was not our home ground but then it progressed into developing our professional skill as the training evolved.

Many OD consultants have a preference for harmony rather than uncertainty, ensuring that people feel good and are happy about the engagement. Indeed, it is important to have a good atmosphere as part of the learning and change process. But we know from learning theory that uncertainty can also be highly stimulating for learning to occur. If we remain in a zone of safety we are unlikely to explore our full potential, and that applies to organizations as well as to athletes and children. Dialogic OD consultants are able to balance the process in ways that provide enough support for people to move into the uncomfortable unknown to discover transformational possibilities (a point taken up in Chapter 13 on hosting containers). In practice this requires, among other things, being able to go with the flow of things rather than holding on tightly to a plan, because it is often out of messiness that new insights spring forth. In this case, many participants found the training sessions a safe playground where they could prepare themselves for reentry into the organization. One participant explained her experience:

It has been important to experiment with how things work out in practice, in a closed safe forum, to be on the playground because it encourages you to go out onto a field at home that doesn’t feel safe. It is important to experience that things don’t necessarily fall apart just because you make mistakes since you have trained with different ways of dealing with these difficulties.

The quote clearly shows how feeling both safe and uncertain produces a generative outcome. Changing behavior feels difficult and uncertain, and therefore becomes a context for seeking safety on the playground, enabling resourcefulness for how to deal with the difficulties. Or one could see it the other way around; the feeling of safety and playfulness encourages one to move out of the comfort zone and into more complex circumstances without feeling disoriented. Either way can be generative and enabling of action and change.

Leader as Role Model

Some of what has made us succeed has been our leader who has been a really good role model in relation to implementing some of these new practices simply by just doing it at the meetings that we have together.

The idea that leadership is central in enabling change in organizations is not new. Even though this can be regarded as good advice in any OD practice, all too often leaders rely on the consultant to model the change, instead of doing it themselves. It cannot be stressed enough that disengaged leaders will impede any change process. It goes beyond the intention of this chapter to address this in more detail, apart from highlighting that a Dialogic OD consultant must engage with what kind of meaning a leader’s disengagement has for people. In such instances the practitioner must further engage the leader with a balanced inquiry into the intentions behind not participating and the risks the leader’s disengagement could pose to the outcome of the process. In our case some of the participants report on the effect of engaged leadership:

It is about showing the good example, to facilitate and being able to push us gently. This is some of what assures that you use your learning in everyday practice—particularly in the beginning.

Being together with your leader during the learning and training sessions really gives you a feeling that we are in it together, that we have a shared focus. And when we came back home our leader could encourage us to continue testing even though everything wasn’t well integrated, it was clear that her leadership training was an advantage for us all since our leader could lead and support us so we used it more than we would have. So our leader has been a good and supportive role model.

It is clear that in this case the participants really found support in an engaged leader who was ready to lead by example and also to facilitate and coach employees so that they were encouraged to try out new practices more often. The leader didn’t miss any session, which reinforced the feeling of teamwork; being together in the different activities gave the participants a feeling of being on the same level as the leader, which opens up dialogic possibilities.

Acknowledging Complexity

I think it is a fundamental change and it does something to people that we now dare to open up to all perspectives and the complexity of our organization even if there are conflicts or dilemmas. This is a fundamental change and now people are more likely to be invited into understanding other people’s opinions which offers a different understanding of what it is we have to work with.

Engaging in dialogical practice requires acknowledging complexity, which in short means that there is always more in and to the world than can be understood and addressed at any given moment in time. What matters is not whether we have understood things as they really are, but instead whether our ways of making sense of the world are productive, or as good as possible. We have to make decisions in a domain of the undecidable, and manage what is unmanageable from within. This is not an emotionally or cognitively easy place to be. Many people strive to find certainty and flee from complexity and reflexivity. Ironically, denying and repressing acknowledgment of the complexity of organizational life produces more and new complexity. The desire for certainty and simple answers requires that we neglect a whole world of contrasting views and ideas and in so doing any decisions we do make necessarily lead to dissonance and resistance in organizations. When decisions do not fit the complexity of the local contexts, “problems” that are frequently addressed do not seem to go away. Often this leads to endless power struggles with their winners and losers. What we gain from acknowledging complexity is a different view of the world that is open to reorientation and the perspectives of others. This leads to decisions that are responsive to a greater number of concerns and needs, and to actions that reduce the experience of complexity. Many who learn the benefits of addressing complexity experience this as eye opening and in our case one participant reflects:

Previously I had the tendency of wanting to reduce complexity, even before we had put our eyes on it. Now I experience that there is a sincere desire to address the complexity before we start to untangle it and there is increased attention to what we need to inquire into and which people we need to invite into the process because we now realize if we don’t admit to the complexity people will just come in later and complain or add to the case and then we have to rework the case which is really undesirable.

While complexity perspectives and the theory of complex responsive processes (discussed in Chapters 6 and 7) may appear complicated in theory, in practice they are surprisingly simple. What these ideas try to convey is an account of how the world seems to operate, arguing that the social world is made up of relational entanglements of things and people, rather than a reconstructed whole made up by separate things. For a Dialogic OD consultant this means that whatever happens is a result of the relational engagement of people responding to an unfolding process; no one can be in complete control of what happens next and what kind of meaning emerges from within the process. When one is able to support and encourage such responsive practices one is likely to experience that what gets produced holds far greater promise of success for more people than more planned and controlled practices allow.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have looked at how an OD consultant works to enable change in people’s actions at work when holding a fluid view of change, where organizations are seen as constantly moving and being in processes of change. These ideas were presented through a case example demonstrating at least three levels of skills that need mastering if one wants to engage seriously in facilitating change in organizations. These entail a capacity to articulate a coherent narrative of the different activities that are incorporated in a suggested process plan as well as an ability to plan and run meetings in a dialogical fashion. The self-reflexive capacity of the consultant was highlighted because it is when the consultant is on stage and in conversation that individuals decide whether to engage in the process or not. Especially in situations of tension and ambiguity a consultant is put to the test.

These theoretical and practical discussions were then followed by a practice-based account of how change was enabled in an organization. Using quotes from the participants, different dimensions of what enabled action were presented and discussed. These dimensions provide a holistic view of what is at stake when a consultant is asked to facilitate a process of change among a group of professionals. These are neither stand-alone dimensions nor are they representative of all processes of change, but they are valid and reliable as dimensions important to any process of change involving a Dialogic OD practitioner.

References

Barrett, F. J. (1998). Creativity and improvisation in jazz and organizations: Implications for organizational learning. Organization Science, 9(5), 605–622.

Barrett, F. J. (2012). Yes to the mess. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press Books.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Cooperrider, D., & Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 1, 129–169.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Losada, M., & Heaphy, E. (2004). The role of positivity and connectivity in the performance of business teams: A nonlinear dynamics model. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 740–765.

Pascale, R., & Sternin, J. (2005). Your company’s secret change agents. Harvard Business Review, 83(5), 72–81.

Pearce, W. B., & Pearce, K. E. (2000). Extending the theory of the coordinated management of meaning (CMM) through a community dialogue process. Communication Theory, 10(4), 405–423.

Rath, T., & Conchie, B. (2008). Strength based leadership. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Rorty, R. (1991). Objectivity, relativism and truth. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Shotter, J. (1993). Cultural politics of everyday life. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Solsø, K. (2012). Hvor blev kroppen af? “Udforskning indefra” i praksis. Erhver-vspsykologi, 10(1), 24–40.

Weick, K. E., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Organizational change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 361–386.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.